Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ana Filipa Ferreira | -- | 2777 | 2023-01-06 10:46:35 | | | |

| 2 | Sirius Huang | + 4 word(s) | 2781 | 2023-01-09 04:03:12 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Ferreira, A.F.; Santiago, J.; Silva, J.V.; Oliveira, P.F.; Fardilha, M. Protein Phosphatases and Their Role in Spermatozoa Function. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/39833 (accessed on 10 March 2026).

Ferreira AF, Santiago J, Silva JV, Oliveira PF, Fardilha M. Protein Phosphatases and Their Role in Spermatozoa Function. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/39833. Accessed March 10, 2026.

Ferreira, Ana F., Joana Santiago, Joana V. Silva, Pedro F. Oliveira, Margarida Fardilha. "Protein Phosphatases and Their Role in Spermatozoa Function" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/39833 (accessed March 10, 2026).

Ferreira, A.F., Santiago, J., Silva, J.V., Oliveira, P.F., & Fardilha, M. (2023, January 06). Protein Phosphatases and Their Role in Spermatozoa Function. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/39833

Ferreira, Ana F., et al. "Protein Phosphatases and Their Role in Spermatozoa Function." Encyclopedia. Web. 06 January, 2023.

Copy Citation

Male fertility relies on the ability of spermatozoa to fertilize the egg in the female reproductive tract (FRT). Spermatozoa acquire activated motility during epididymal maturation; however, to be capable of fertilization, they must achieve hyperactivated motility in the FRT. Extensive research found that three protein phosphatases (PPs) are crucial to sperm motility regulation, the sperm-specific protein phosphatase type 1 (PP1) isoform gamma 2 (PP1γ2), protein phosphatase type 2A (PP2A) and protein phosphatase type 2B (PP2B).

sperm motility

capacitation

protein phosphatase

1. Introduction

The equilibrium of protein phosphorylation systems is essential to maintain cellular viability and function. Indeed, it is the most common post-translational type of modification in eukaryotes [1][2]. Since spermatozoa are virtually transcriptionally and translationally inactive, their specific functions are mediated mainly by protein phosphorylation [3][4][5]. Together with the extensively researched protein kinases (PKs), sperm-specific protein phosphatases (PPs) are known to have critical roles in spermatozoa maturation, especially regarding sperm motility acquisition during epididymal transit (Figure 1a) and sperm hyperactivation in the FRT (Figure 1b) [3][6][7][8][9]. According to Smith et al., in bovine caput epididymis, immotile spermatozoa have higher phosphatase activity when compared to caudal motile sperm [10].

Figure 1. Representation of the PPs and PKs involved in activated motility acquisition in the epididymis, as well as in hyperactivation in the female reproductive tract. The colour green represents catalytic activity, whereas red stands for enzymatic inactivity. (a) Epididymis representation including its three epididymal subdivisions: caput, corpus, and cauda, as well as deferent and efferent ducts. In caput epididymis spermatozoa are immotile, the PPs PP1γ2, PP2A, PP2B and the PK GSK3 present catalytic activity, while PKA is inactive. In cauda, mature and progressively motile sperm are characterized by inactive PP1γ2, PP2A, PP2B and GSK3 and active PKA. (b) Feminine reproductive tract representation where hyperactivated spermatozoa presents inactive PP1γ2 and PP2A, whereas PP2B, GSK3 and PKA present catalytic activity.

2. Protein Phosphatase Type 1 (PP1)

PP1 is the predominant PP identified in the spermatozoon [10][11]. Since the first description of its association with sperm motility in 1996 [6], PP1’s role in the signaling events involved in spermatozoa motility acquisition within the epididymis has been investigated [7][11][12]. The catalytic subunit of PP1 is highly conserved among eukaryotes; it consists of a single domain of ~30 kDa that binds to regulatory subunits. PP1 catalytic activity is due to the channel formed by three β-sheets of the β-sandwich, along with two metal ions (Manganese (Mn) and Iron (Fe)) coordinated by six amino acid residues (one Asn, three His, and two Asp) that form the active site [13][14]. In mammals, the catalytic subunit of PP1 presents four distinct isoforms—PP1α, PP1β, PP1γ1 and PP1γ2—encoded in three different genes (Ppp1ca, Ppp1cb, Ppp1cc). PP1γ1 and PP1γ2 result from alternative splicing of the same gene, Ppp1cc, being the first ubiquitously expressed, along with PP1α and PP1β, and the latest testis-enriched and sperm-specific isoform. The two isoforms’ amino acid sequences are almost identical, differing only at the C-termini [10][11][15][16]. The different isoforms of the catalytic subunit present distinct subcellular localization patterns and exist in the cell in association with regulatory subunits, the PP1 interacting proteins [PIPs; also known as regulatory interactors of protein phosphatase one (RIPPOs)] [17][18][19]. More than 800 PIPs were identified so far, which guide PP1 action within the cell, specify PP1 substrates and regulate PP1 activity [20][21].

Protein Phosphatase 1 Gamma 2 (PP1γ2)

PP1γ2 is the testis-enriched and sperm-specific PP1, which in mammals appears to be the principal isoform responsible for PP1 activity in spermatozoa [6][10][11]. It differs from the PP1γ1 on the C-terminal and is distributed throughout the flagellum, midpiece, and posterior region of the head of the spermatozoon [11][17]. Numerous studies showed that the decrease of PP1γ2 activity is associated with increased motility in the caudal epididymis, whereas immotile caput spermatozoa present high levels of PP1γ2 activity. During capacitation, the downregulation of this PP activity in spermatozoon was also evident [6][10][22][23]. Phosphatase activity inhibition in caput epididymis, by both PP1 inhibitors CA and OA, was also able to induce motility [6][10]. Additionally, Ppp1cc gene knockout in mice, which causes the loss of both PP1γ1 and PP1γ2, resulted in impaired spermatogenesis and subsequent male infertility [24][25]. Conditional knockout of only PP1γ2 resulted in the same phenotype, strongly suggesting that Ppp1cc knockout mice infertility is likely due to the loss of PP1γ2 [26]. Besides, PP1γ2 transgenic expression in Ppp1cc null mice was able to restore sperm function and fertility [27]. Hence, it is thought that PP1γ2 is responsible for the role of PP1 in motility acquisition in the epididymis, hyperactivation and acrosome reaction [12].

In sperm, PP1γ2 activity is mainly regulated by three specific inhibitors, protein phosphatase inhibitor 2 (PPP1R2, also known as I2), protein phosphatase 1 regulatory subunit 7 (PPP1R7, also known as SDS22) and protein phosphatase 1 regulatory subunit 11 (PPP1R11, also known as I3), whose association with PP1γ2 varies during epididymal sperm maturation [5][28][29]. In brief, PP1γ2 is solely bound to I3 in immotile spermatozoa of the caput epididymis, while in caudal spermatozoa it is bound to all three inhibitors. These alterations play an important role in motility development because they can modulate PP1γ2 activity [28]. In 2013, a PPP1R2 isoform was identified in human spermatozoa, the protein phosphatase inhibitor 2-like (PPP1R2P3), which appears to be present only in caudal spermatozoa, inhibiting PP1γ2 and therefore contributing to motility acquisition. Due to Thr73 being substituted by proline, PPP1R2P3 cannot be phosphorylated by glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3) [30]. Furthermore, recently Schwartz et al. identified another possible PP1γ2 binding protein, which is CCDC181. Despite little being known about their interaction, the authors hypothesize that CCDC181 has a relevant role in generating and regulating flagellar and ciliary motility [31].

GSK3 (recently reviewed in Dey et al. 2019 [7]) was discovered to interact with PP1γ2 in the spermatozoon, playing an essential role in its activation [6][32]. Similar to PP1γ2, GSK3 presents six times more catalytic activity in immotile caput spermatozoa when compared to motile caudal sperm [32][33]. Currently, it is known that GSK3 regulates I2 binding to PP1γ2; however, it is only speculated that the other PP1γ2 inhibitors referred (SDS22 and I3) are also regulated by phosphorylation [6][28].

3. Protein Phosphatase Type 2A (PP2A)

PP2A activity was first documented in mammalian spermatozoa in 1996 by Vijayaraghavan et al. [6]. This Ser/Thr PP consists of a catalytic subunit (PP2A-C), which has two isoforms (α and β), a scaffolding subunit (PP2A-A, also with two isoforms) and a regulatory subunit (PP2A-B) [34][35]. The catalytic subunit of PP2A (36 kDa), which is one of the most conserved in eukaryotes, and the scaffolding subunit (65 kDa) form the enzyme core that can associate with different regulatory subunits giving rise tothe PP2A holoenzyme. The catalytic subunit consists of a typical α/β fold and contains two Mn ions at the enzyme’s active site [36][37]. It can be covalently modified by either Tyr phosphorylation or carboxymethylation [35][37].

It was reported that PP2A plays a role in both bovine and human sperm motility acquisition. Similar to PP1γ2, higher levels of this PP activity were identified in immotile caput spermatozoa, and downregulation of its activity was evident in both caudal motile and hyperactivated spermatozoa. In addition, inhibition of PP2A prevented motility initiation in caput epididymal spermatozoa but was able to stimulate it at the caudal sperm level. Changes in PP2A methylation also modify spermatozoa movement, as methylated PP2A is catalytically inactive in caudal spermatozoa [22][35][38]. GSK3 is a known target of PP2A, since its phosphorylation was increased following PP2A inhibition. Hence, PP2A is thought to be involved in sperm motility mainly by regulating GSK3 activity [35].

4. Phosphoprotein Phosphatase Type 2B (PP2B)

PP2B, also known as calcineurin, is a Ser/Thr PP regulated by Ca2+, which was also found in humans and other mammalian spermatozoa [8][39]. This PP is Ca2+/calmodulin (CAM)-dependent, meaning that it is inactive when it is not associated with Ca2+-CAM [39]. PP2B is composed of two subunits, catalytic and regulatory. There are three isoforms of the catalytic subunit (PPP3CA, PPP3CB, and PPP3CC), PPP3CC being the sperm-specific catalytic isoform. The regulatory subunit also presents two isoforms PPP3R1 and PPP3R2, the latest being present in spermatozoa. Absence of both sperm-specific isoforms due to gene knockout results in male infertility [8][9][40][41]. PPP3CC contains four regions, the catalytic domain, a regulatory subunit binding segment, a CAM-binding segment and an autoinhibitory helix [42][43]. As with the other PPs, the active site of PP2B contains two metal ions, Fe and Zn, and six amino acid residues (three His, two Asn, and one Asp) [41][42].

Upon the increase in intracellular Ca2+, CAM binds to the PPP3CC subunit, through the CAM binding region, causing the activation of the enzyme, by allowing it to access its substrates [7][41]. Since it was shown in 1990 that immature caput spermatozoa present higher levels of Ca2+ when compared to caudal sperm, a decline in PP2B activity throughout the epididymis journey was expected and further verified by Dey et al. in 2019 [8]. Furthermore, it was demonstrated that PP2B increases its activity during capacitation [8][44]. PP2B regulates GSK3 phosphorylation, preferentially dephosphorylating the GSK3α isoform, contrarily to PP1γ2 and PP2A which target both isoforms [7][8].

5. PP1γ2, PP2A and PP2B Interplay in the Regulation of Sperm Motility

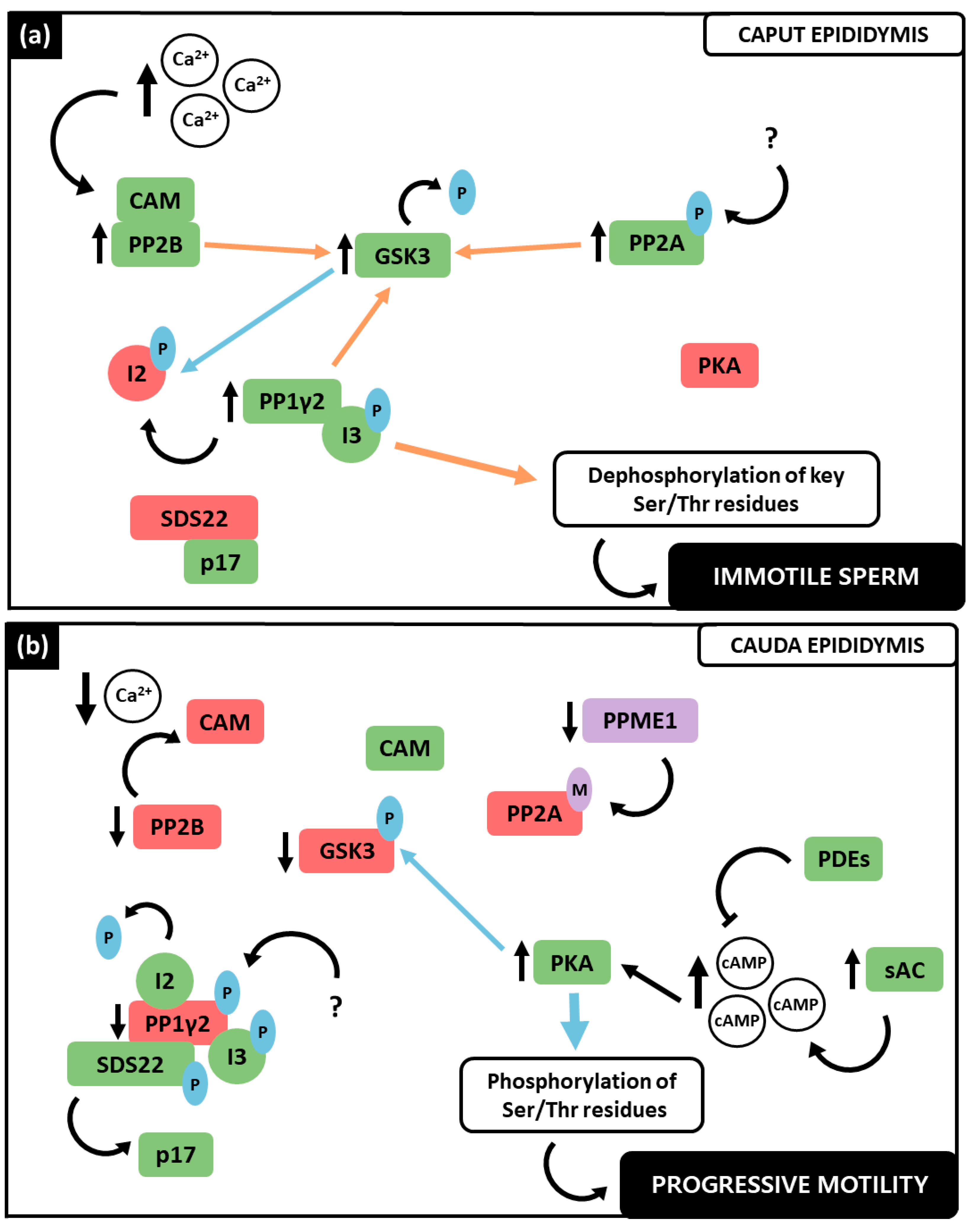

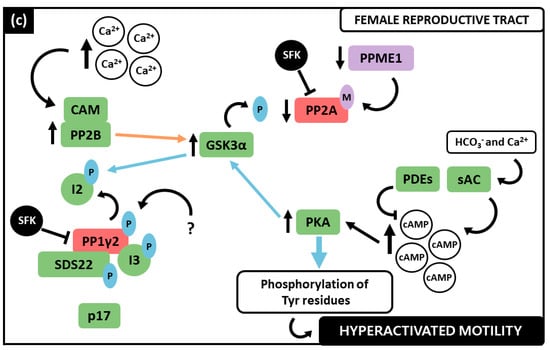

Taken together, the data exposed previously postulate that PP1γ2, PP2A and PP2B are strongly involved in spermatozoa motility regulation. In the last decades, the signaling pathways in which these PPs are involved have been deeply investigated (Figure 2). Indeed, apart from their individual role, an interplay between the three PPs has been proposed [3][7][12]. Notably, these PPs play distinct roles in motility at the different stages of spermatozoa maturation throughout the epididymis, as well as in hyperactivated motility. PP1γ2, PP2A and PP2B were collectively found to have consistently higher activity in the caput region (Figure 2a), where spermatozoa are immature and immotile, whereas they demonstrated low catalytic activity levels in the cauda (Figure 2b), where spermatozoa have acquired activated motility [7][12]. This suggests that the decrease of their catalytic activity is a requirement for motility acquisition and, when these PPs remain activated in caudal spermatozoa, motility acquisition is not achieved [5][10]. Concerning hyperactivated motility (Figure 2c), PP1γ2 and PP2A were found still catalytically inactive, while, paradoxically, PP2B presented phosphatase activity [7][8].

Figure 2. Interplay between the PPs, PP1γ2, PP2A and PP2B, and PKs, GSK3 and PKA, regarding sperm motility regulation. The color green represents catalytic activity, whereas red stands for enzymatic inactivity. Blue arrows define phosphorylation reactions, while orange represents dephosphorylation processes. (a) In caput immotile sperm, Ca2+ increase promotes PP2B interaction with Ca2+-CAM complex that activates it. PP2B dephosphorylates GSK3α increasing its activity. Phosphorylated PP2A also contributes to the phosphorylation of both GSK3 isoforms. GSK3 phosphorylates the I2 that disassociates from PP1γ2, rendering it active, solely in a complex with I3. The inhibitor SDS22 is bound to p17. PP1γ2 dephosphorylates GSK3 and Ser/Thr residues, resulting in immotile spermatozoa. PKA presents no significant catalytic activity. (b) In cauda epididymis, Ca2+ concentration is lower, causing CAM dissociation from PP2B and its subsequent inactivity. PPME1 decreases allowing PP2A methylation and inactivity. Simultaneously, sAC is activated and produces cAMP, which in turn activates PKA. cAMP degradation is due to PDE activity. PKA phosphorylates PP1γ2 and GSK3 that decreases its activity and is no longer able to phosphorylate I2, which forms a complex with PP1γ2 and SDS22 that dissociates from p17. Lastly, PKA’s increased activity causes phosphorylation of Ser/Thr residues which are a requirement for activated motility acquisition. (c) The increase in Ca2+ once again activates PP2B that dephosphorylates GSK3α rendering it active and able to phosphorylate I2. Due to sAC activation by HCO3− and Ca2+, cAMP further increases and stimulates PKA activity. PKA phosphorylates GSK3. PP1y2 is phosphorylated and in a complex with SDS22 and I3. SFK also contributes to decrease PP1y2 activity along with PP2A, that remains methylated. The increase in phosphorylation of Tyr residues contributes to achieve hyperactivated motility.

Considering the current state of the art, an interplay between both the PPs (PP1γ2, PP2A and PP2B) and PKs (GSK3 and PKA) can be proposed (Figure 2). In caput spermatozoa (Figure 2a), the increase in intracellular Ca2+ activates PP2B by promoting its interaction with the Ca2+-CAM complex. Consequently, PP2B preferentially dephosphorylates GSK3α at its inhibitory residue Ser21, activating it [8]. Synergistically, at this stage active PP2A is demethylated and phosphorylated, therefore being able to also dephosphorylate both GSK3 isoforms [35]. The PK that phosphorylates PP2A is still unclear. Active GSK3 phosphorylates the PP1γ2 inhibitor I2 at Thr73, which results in active PP1γ2, in a complex with only I3, since SDS22 is bound to p17 [29][35]. PP1γ2 not only contributes to GSK3 dephosphorylation, but also to key Ser and Thr residues dephosphorylation [12][35]. In caput spermatozoa, PKA presents no significant catalytic activity (recently reviewed by Dey et al., 2019 [7]).

During the spermatozoa’s journey through the epididymis (Figure 2b), the Ca2+ influx decreases, along with PP2B activity, rendering it inactive at caudal level and therefore unable to dephosphorylate the GSK3α isoform [8]. GSK3 dephosphorylation is further affected by the decrease in protein phosphatase methylesterase 1 (PPME1) activity in caudal spermatozoa, which increases PP2A methylation causing its inactivation. Highly phosphorylated GSK3 at Ser residues is inactive and incapable of phosphorylating I2, which can inhibit PP1γ2 [35]. Simultaneously, SDS22 is free from its interaction with p17, being in a complex with PP1γ2 as well [29]. The decrease in the activity of the Ser/Thr PPs, which causes a notable decrease in dephosphorylation, and an increase in the number of phosphorylated residues due to PKA activity, was observed in caudal spermatozoa [7][45][46]. The sAC, whose activity is regulated by HCO3− and Ca2+ concentration, is activated and produces cAMP, activating PKA [46]. The concentration of cAMP in spermatozoa is also regulated by phosphodiesterases (PDEs) that can degrade it, being the equilibrium of sAC and PDE activity responsible for cAMP levels in spermatozoa [7]. Overall, active PKA in caudal spermatozoa not only phosphorylates both GSK3 isoforms (Ser21/9), but also other proteins, which seems to be a requirement for motility acquisition in the mature spermatozoon [3][7][28]. PP1γ2 was shown to be phosphorylated in caudal spermatozoa at its Thr320. The underlining mechanism is still unknown, but it is speculated that a cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) is responsible for this residue’s phosphorylation [5][7][47].

At the FRT, hyperactivated motility is required for successful fertilization and both PP and PK play important roles [8][48] (Figure 2c). Ca2+ influx increases, again inducing PP2B activity, which in turn dephosphorylates GSK3α, being both enzymes active during capacitation [8]. GSK3α is now able to phosphorylate I2 which disassociates from PP1γ2. The other two inhibitors remain in a complex with this PP, rendering it still inactive. PP2A also remains inactive since it is methylated [12]. It was proposed by Battistone and colleagues that PPs downregulation during capacitation is also mediated by a Src family kinase (SFK). They showed that spermatozoon capacitating in the presence of a SFK inhibitor (SKI606) presented a decrease in phosphorylation levels, which was overcome by exposure to a PP inhibitor (OA). In addition, incubation with SKI606 also affected motility parameters which were similar to those of non-capacitated spermatozoa [22]. Concomitantly, the high concentrations of Ca2+ and HCO3− stimulate cAMP production and a subsequent increase in PKA activity, which increases phosphorylation in Tyr residues among several known substrates within the spermatozoon, that seem to be required to achieve hyperactivated motility [22][49][50]. Remarkably, both PP2B and the GSK3α isoform present increased activity in hyperactivated spermatozoa, similar to their activity in caput immotile spermatozoa. Although many authors have been suggesting that the decrease in PP catalytic activity and concomitant increase in PK is a requirement for sperm motility, more recently, PP2B catalytic activity appeared to be essential for successful hyperactivation, accordingly to Dey et al. [8][9][22]. Comparing to activated progressive motility, the mechanisms that underline hyperactivated motility acquisition are more complex and are affected by alterations other than protein phosphorylation, which could explain the disparity between the PPs activity during this process [3][7][8][9][22][51].

Taking everything into account, the crosstalk between PP1γ2, PP2A and PP2B, as well as GSK3 and PKA, is essential both during spermatozoa maturation along the epididymis and capacitation at the FRT, since they determine the phosphorylation status of spermatozoa proteins, which appears to be crucial to initiate and maintain activated and hyperactivated motility. Regardless of the countless studies made to understand the biochemical mechanisms underlining sperm motility, several inconsistencies are yet to be solved and many protein interactions unveiled. For instance, some studies disagree on the state of PP2B activity during capacitation. Signorelli and colleagues verified its inactivity at this stage, while Dey et al. verified that PP2B presented catalytic activity during capacitation [8][9]. Furthermore, the PK and mechanisms that phosphorylates PP1γ2 at Thr320 are still unclear [5][7][47].

References

- Rebelo, S.; Santos, M.; Martins, F.; da Cruz e Silva, E.F.; da Cruz e Silva, O.A.B. Protein Phosphatase 1 Is a Key Player in Nuclear Events. Cell Signal. 2015, 27, 2589–2598.

- Cohen, P. The Origins of Protein Phosphorylation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2002, 4, E127–E130.

- Gervasi, M.G.; Visconti, P.E. Molecular Changes and Signaling Events Occurring in Spermatozoa during Epididymal Maturation. Andrology 2017, 5, 204–218.

- Baldi, E.; Luconi, M.; Bonaccorsi, L.; Forti, G. Signal Transduction Pathways in Human Spermatozoa. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2002, 53, 121–131.

- Fardilha, M.; Esteves, S.L.C.; Korrodi-Gregório, L.; Pelech, S.; da Cruz e Silva, O.A.B.; da Cruz e Silva, E. Protein Phosphatase 1 Complexes Modulate Sperm Motility and Present Novel Targets for Male Infertility. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2011, 17, 466–477.

- Vijayaraghavan, S.; Stephens, D.; Trautman, K.; Smith, G.; Khatra, B.; Cruz e Silva, E.F.; Greengard, P. Sperm Motility Development in the Epididymis Is Associated with Decreased Glycogen Synthase Kinase-3 and Protein Phosphatase 1 Activity. Biol. Reprod. 1996, 54, 709–718.

- Dey, S.; Brothag, C.; Vijayaraghavan, S. Signaling Enzymes Required for Sperm Maturation and Fertilization in Mammals. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019, 7, 341.

- Dey, S.; Eisa, A.; Kline, D.; Wagner, F.F.; Abeysirigunawardena, S.; Vijayaraghavan, S. Roles of Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3 Alpha and Calcineurin in Regulating the Ability of Sperm to Fertilize Eggs. FASEB J. 2019, 34, 1247–1269.

- Signorelli, J.R.; Díaz, E.S.; Fara, K.; Barón, L.; Morales, P. Protein Phosphatases Decrease Their Activity during Capacitation: A New Requirement for This Event. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e81286.

- Smith, G.D.; Wolf, D.P.; Trautman, K.; Cruz e Silva, E.F.; Greengard, P.; Srinivasan, V. Primate Sperm Contain Protein Phosphatase 1, a Biochemical Mediator of Motility. Biol. Reprod. 1996, 54, 719–727.

- Fardilha, M.; Esteves, S.; Korrodi-Gregório, L.; Vintém, A.; Domingues, S.; Rebelo, S.; Morrice, N.; Cohen, P.; da Cruz e Silva, O.; da Cruz e Silva, E. Identification of the Human Testis Protein Phosphatase 1 Interactome. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2011, 82, 1403–1415.

- Freitas, M.J.; Vijayaraghavan, S.; Fardilha, M. Signaling Mechanisms in Mammalian Sperm Motility. Biol. Reprod. 2017, 96, 2–12.

- Goldberg, J.; Huang, H.B.; Kwon, Y.G.; Greengard, P.; Nairn, A.C.; Kuriyan, J. Three-Dimensional Structure of the Catalytic Subunit of Protein Serine/Threonine Phosphatase-1. Nature 1995, 376, 745–753.

- Barford, D.; Das, A.K.; Egloff, M.P. The Structure and Mechanism of Protein Phosphatases: Insights into Catalysis and Regulation. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 1998, 27, 133–164.

- Da Cruz e Silva, E.; Fox, C.A.; Ouimet, C.C.; Gustafson, E.; Watson, S.J.; Greengard, P. Differential Expression of Protein Phosphatase 1 Isoforms in Mammalian Brain. J. Neurosci. 1995, 15, 3375–3389.

- Berndt, N.; Campbell, D.G.; Caudwell, F.B.; Cohen, P.; da Cruz e Silva, E.F.; da Cruz e Silva, O.B.; Cohen, P.T.W. Isolation and Sequence Analysis of a CDNA Clone Encoding a Type-1 Protein Phosphatase Catalytic Subunit: Homology with Protein Phosphatase 2A. FEBS Lett. 1987, 223, 340–346.

- Fardilha, M.; Esteves, S.L.C.; Korrodi-Gregorio, L.; da Cruz e Silva, O.A.B.; da Cruz e Silva, E.F. The Physiological Relevance of Protein Phosphatase 1 and Its Interacting Proteins to Health and Disease. Curr. Med. Chem. 2010, 17, 3996–4017.

- Lee, J.H.; You, J.; Dobrota, E.; Skalnik, D.G. Identification and Characterization of a Novel Human PP1 Phosphatase Complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 24466.

- Wu, D.; De Wever, V.; Derua, R.; Winkler, C.; Beullens, M.; Van Eynde, A.; Bollen, M. A Substrate-Trapping Strategy for Protein Phosphatase PP1 Holoenzymes Using Hypoactive Subunit Fusions. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 15152–15162.

- Verbinnen, I.; Ferreira, M.; Bollen, M. Biogenesis and Activity Regulation of Protein Phosphatase 1. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2017, 45, 89–99.

- Alanis-Lobato, G.; Andrade-Navarro, M.A.; Schaefer, M.H. HIPPIE v2.0: Enhancing Meaningfulness and Reliability of Protein-Protein Interaction Networks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, gkw985.

- Battistone, M.A.; da Ros, V.G.; Salicioni, A.M.; Navarrete, F.A.; Krapf, D.; Visconti, P.E.; Cuasnicú, P.S. Functional Human Sperm Capacitation Requires Both Bicarbonate-Dependent PKA Activation and down-Regulation of Ser/Thr Phosphatases by Src Family Kinases. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2013, 19, 570.

- Chakrabarti, R.; Cheng, L.; Puri, P.; Soler, D.; Vijayaraghavan, S. Protein Phosphatase PP1 Gamma 2 in Sperm Morphogenesis and Epididymal Initiation of Sperm Motility. Asian J. Androl. 2007, 9, 445–452.

- Varmuza, S.; Jurisicova, A.; Okano, K.; Hudson, J.; Boekelheide, K.; Shipp, E.B. Spermiogenesis is Impaired in Mice Bearing a Targeted Mutation in the Protein Phosphatase 1cγ Gene. Dev. Biol. 1999, 205, 98–110.

- Chakrabarti, R.; Kline, D.; Lu, J.; Orth, J.; Pilder, S.; Vijayaraghavan, S. Analysis of Ppp1cc-Null Mice Suggests a Role for PP1gamma2 in Sperm Morphogenesis. Biol. Reprod. 2007, 76, 992–1001.

- Sinha, N.; Puri, P.; Nairn, A.C.; Vijayaraghavan, S. Selective Ablation of Ppp1cc Gene in Testicular Germ Cells Causes Oligo-Teratozoospermia and Infertility in Mice. Biol. Reprod. 2013, 89, 1–15.

- Sinha, N.; Pilder, S.; Vijayaraghavan, S. Significant Expression Levels of Transgenic PPP1CC2 in Testis and Sperm Are Required to Overcome the Male Infertility Phenotype of Ppp1cc Null Mice. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e47623.

- Goswami, S.; Korrodi-Gregório, L.; Sinha, N.; Bhutada, S.; Bhattacharjee, R.; Kline, D.; Vijayaraghavan, S. Regulators of the Protein Phosphatase PP1γ2, PPP1R2, PPP1R7, and PPP1R11 Are Involved in Epididymal Sperm Maturation. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 3105–3118.

- Mishra, S.; Somanath, P.R.; Huang, Z.; Vijayaraghavan, S. Binding and Inactivation of the Germ Cell-Specific Protein Phosphatase PP1gamma2 by Sds22 during Epididymal Sperm Maturation. Biol. Reprod. 2003, 69, 1572–1579.

- Korrodi-Gregório, L.; Ferreira, M.; Vintém, A.P.; Wu, W.; Muller, T.; Marcus, K.; Vijayaraghavan, S.; Brautigan, D.L.; da Cruz e Silva, O.A.B.; Fardilha, M.; et al. Identification and Characterization of Two Distinct PPP1R2 Isoforms in Human Spermatozoa. BMC Cell Biol. 2013, 14, 15.

- Schwarz, T.; Prieler, B.; Schmid, J.A.; Grzmil, P.; Neesen, J. Ccdc181 Is a Microtubule-Binding Protein That Interacts with Hook1 in Haploid Male Germ Cells and Localizes to the Sperm Tail and Motile Cilia. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2017, 96, 276–288.

- Somanath, P.R.; Jack, S.L.; Vijayaraghavan, S. Changes in Sperm Glycogen Synthase Kinase-3 Serine Phosphorylation and Activity Accompany Motility Initiation and Stimulation. J. Androl. 2004, 25, 605–617.

- Vijayaraghavan, S.; Mohan, J.; Gray, H.; Khatra, B.; Carr, D.W. A Role for Phosphorylation of Glycogen Synthase Kinase-3alpha in Bovine Sperm Motility Regulation. Biol. Reprod. 2000, 62, 1647–1654.

- Janssens, V.; Goris, J. Protein Phosphatase 2A: A Highly Regulated Family of Serine/Threonine Phosphatases Implicated in Cell Growth and Signalling. Biochem. J. 2001, 353, 417–439.

- Dudiki, T.; Kadunganattil, S.; Ferrara, J.K.; Kline, D.W.; Vijayaraghavan, S. Changes in Carboxy Methylation and Tyrosine Phosphorylation of Protein Phosphatase PP2A Are Associated with Epididymal Sperm Maturation and Motility. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0141961.

- Xing, Y.; Xu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Jeffrey, P.D.; Chao, Y.; Lin, Z.; Li, Z.; Strack, S.; Stock, J.B.; Shi, Y. Structure of Protein Phosphatase 2A Core Enzyme Bound to Tumor-Inducing Toxins. Cell 2006, 127, 341–353.

- Sontag, E. Protein Phosphatase 2A: The Trojan Horse of Cellular Signaling. Cell Signal. 2001, 13, 7–16.

- Morales, P.; Signorelli, J.R.; Diaz, E.S. Protein Phosphatase-Type 2A (PP2A) Is Involved in the Initial Events of Human Sperm Capacitation. Biol. Reprod. 2010, 83, 172.

- Ahmad, K.; Bracho, G.E.; Wolf, D.P.; Tash, J.S. Regulation of Human Sperm Motility and Hyperactivation Components by Calcium, Calmodulin, and Protein Phosphatases. Arch. Androl. 1995, 35, 187–208.

- Miyata, H.; Satouh, Y.; Mashiko, D.; Muto, M.; Nozawa, K.; Shiba, K.; Fujihara, Y.; Isotani, A.; Inaba, K.; Ikawa, M. Sperm Calcineurin Inhibition Prevents Mouse Fertility with Implications for Male Contraceptive. Science 2015, 350, 442–445.

- Rusnak, F.; Mertz, P. Calcineurin: Form and Function. Physiol. Rev. 2000, 80, 1483–1521.

- Kissinger, C.R.; Parge, H.E.; Knighton, D.R.; Lewis, C.T.; Pelletier, L.A.; Tempczyk, A.; Kalish, V.J.; Tucker, K.D.; Showalter, R.E.; Moomaw, E.W.; et al. Crystal Structures of Human Calcineurin and the Human FKBP12–FK506–Calcineurin Complex. Nature 1995, 378, 641–644.

- Jin, L.; Harrison, S.C. Crystal Structure of Human Calcineurin Complexed with Cyclosporin A and Human Cyclophilin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 13522–13526.

- Vijayaraghavan, S.; Hoskins, D.D. Changes in the Mitochondrial Calcium Influx and Efflux Properties Are Responsible for the Decline in Sperm Calcium during Epididymal Maturation. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 1990, 25, 186–194.

- Vadnais, M.L.; Aghajanian, H.K.; Lin, A.; Gerton, G.L. Signaling in Sperm: Toward a Molecular Understanding of the Acquisition of Sperm Motility in the Mouse Epididymis. Biol. Reprod. 2013, 89, 127.

- Buffone, M.G.; Wertheimer, E.V.; Visconti, P.E.; Krapf, D. Central Role of Soluble Adenylyl Cyclase and CAMP in Sperm Physiology. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Mol. Basis Dis. 2014, 1842, 2610–2620.

- Salvi, F.; Hoermann, B.; del Pino García, J.; Fontanillo, M.; Derua, R.; Beullens, M.; Bollen, M.; Barabas, O.; Köhn, M. Towards Dissecting the Mechanism of Protein Phosphatase-1 Inhibition by Its C-Terminal Phosphorylation. ChemBioChem 2021, 22, 834–838.

- Jin, S.K.; Yang, W.X. Factors and Pathways Involved in Capacitation: How Are They Regulated? Oncotarget 2017, 8, 3600.

- Chen, Y.; Cann, M.J.; Litvin, T.N.; Iourgenko, V.; Sinclair, M.L.; Levin, L.R.; Buck, J. Soluble Adenylyl Cyclase as an Evolutionarily Conserved Bicarbonate Sensor. Science 2000, 289, 625–628.

- Xie, F.; Garcia, M.A.; Carlson, A.E.; Schuh, S.M.; Babcock, D.F.; Jaiswal, B.S.; Gossen, J.A.; Esposito, G.; van Duin, M.; Conti, M. Soluble Adenylyl Cyclase (SAC) Is Indispensable for Sperm Function and Fertilization. Dev. Biol. 2006, 296, 353–362.

- Freitas, M.J.; Silva, J.V.; Brothag, C.; Regadas-Correia, B.; Fardilha, M.; Vijayaraghavan, S. Isoform-Specific GSK3A Activity Is Negatively Correlated with Human Sperm Motility. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2019, 25, 171–183.

More

Information

Subjects:

Biochemistry & Molecular Biology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

837

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

09 Jan 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No