1. Anticancer Activity of Avicennia marina

Two new flavonoids, luteolin 7-O-methylether 3′-O-β-d-glucoside and its galactoside analogue, provided from the methanol extract of aerial parts of

A. marina, proved to be cytotoxic against cell line BT-20 of human breast cancer, showing ED50 values of 16 and 18 μg/mL, respectively

[1].

From the twigs of

A. marina, seven new naphthoquinone derivatives were isolated: avicennones A−G together with five known natural products. Tests were undertaken using Avicennone A, stenocarpoquinone B, avicequinone C, avicenol A, avicenol C, and a mixture of Avicennone D and E. These were used against L-929 mouse fibroblasts and K562 human chronic myeloid leukemia cells to demonstrate an anti-proliferative effect, as well as cytotoxic activity against the HeLa human cervix carcinoma cell line. Antiproliferative effects were shown against L-929 (GI50 values of 1.2, 0.8, and 4.4 μg/mL, respectively) and K562 (GI50 values of 0.2, 1.1, and 7.5 μg/mL, respectively) by stenocarpoquinone B, avicequinone C, and the mixture of avicennone D and F; however, these appeared at lower values compared to the standard paclitaxel (GI50 values of 0.1 and 0.01 μg/mL, respectively). These compounds also proved to be cytotoxic toward the HeLa cell line, with CC50 values of 4.3, 3.2, and 13.1 μg/mL, respectively, which were higher compared with the positive control (CC50 value of 0.01 μg/mL). An interesting point is that all of the active compounds share the

p-dione of the naphthoquinone core as a structural element. Referring to the other compounds, instead, they have shown little activity against the aforementioned cancer cell lines

[2].

Methanolic extract of

A. marina leaves exhibited cytotoxic activity on human breast MDA-MB 231 cancer cells, with an IC50 value of 480 µg/mL, while it had no significant effect against normal cell line L929. In addition, the extract induced apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner, and also showed a time-dependent growth inhibition effect of 40%, 44%, and 59% after 24, 48, and 72 h of treatment, respectively

[3].

Ethanol extract from

A. marina leaves was found to be cytotoxic against human promyelocytic leukaemia HL-60 cells, with IC50 values of 600, 400, and 280 µg/mL after 24, 48, and 72 h, respectively, in a concentration- and time-dependent manner. Treated cells, compared to the control cells, appeared smaller, less refracted, membrane blebbing, and with more granular material. Moreover, flow cytometric analysis confirmed that apoptosis was the mechanism of cell death induced by the extract, and revealed that a concentration of 600 µg/mL induced 62% apoptosis at 24 h

[4].

Methanolic and aqueous extracts of

A. marina leaves were found to be cytotoxic against human promyelocytic leukemia HL-60 cells (IC50 values of 277.129 and 291.773 µg/mL, respectively) and the human non-small cell lung cancer NCI-H23 cell line (IC50 values of 221.173 and 237.179 µg/mL, respectively) with an effect comparable to that of doxorubicin

[5].

The methanolic extract of

A. marina stem bark exhibited cytotoxicity against HL-60 and NCI-H23 (IC50 values of 297.934 and 210.987 µg/mL, respectively) as well as the aqueous extract was found to be cytotoxic on HL-60 and NCI-H23 (IC50 values of 281.175 and 220.127 µg/mL, respectively). The extracts displayed comparable cytotoxic IC50 values with the standard doxorubicin and showed negligible toxicity against the human embryonic kidney (HEK-293T) normal cell line

[6].

Ethyl acetate extract of

A. marina leaves and stems displayed, after 48 h, 65% and 75% growth inhibition of the breast adenocarcinoma cell line MCF-7, at, 100 µg/mL and 200 µg/mL, respectively. Further, 100 µg/mL of the extract showed 10% apoptosis at 24 h, while no increasing value in apoptosis was found at 48 h or at 72 h. Nevertheless, increasing the extract concentration to 200 µg/mL displayed 25% apoptosis at 24 h, with an increase of 55% and 75% at 48 h and 72 h, respectively

[7]. Due to the lack of literature regarding the molecular mechanisms of cell death induced by

A. marina extracts, Esau et al. decided to focus on the intracellular pathways involved in the apoptotic effect of ethyl acetate extract against the MCF-7 cell line. Their study proved that the 200 µg/mL of extract concentration unleashed ROS-mediated autophagy, as well as caspase-independent apoptosis.

Further studies by Huang et al.

[8] focused on the potential association between the phenol and flavonoid contents of water, ethanol, methanol, and ethyl acetate extracts of

A. marina leaves with their anticancer activities. In vitro experiments were performed on three human breast cancer cell lines (AU565, MDA-MB-231, and BT483), two human liver cancer cell lines (HepG2 and Huh7), and one normal cell line (NIH3T3). The outcomes revealed that the ethyl acetate extract of

A. marina was the one carrying the highest concentrations of flavonoids and phenolic compounds, and proved, at the same time, that its anticancer activities were the most effective ones. Furthermore, ethyl acetate extract was found to be unable to inhibit the proliferation of NIH 3T3 cells at 40–80-μg/mL. Therefore, subsequent analyses were performed at a concentration range of 40–80 μg/mL following treatments with ethyl acetate extract. In addition, the colony formation in soft agar of AU565, BT483, HepG2, and Huh7 cancer cell lines was reduced after 14–21 days of treatment with the extract. Furthermore, F2-5, F3-2-9, and F3-2-10 ethyl acetate fractions were all obtained by performing column chromatography, and showed higher cytotoxic activity compared to other fractions against AU565, BT483, HepG2, and Huh7 cell lines, displaying IC50 values of 0.75, 0.85, 0.79, and 15.6 μg/mL, respectively. The

1H-NMR and

13C-NMR profiles demonstrated that the F3-2-10 fraction contained avicennones D (

4) and E (

5). The suppression of MDA-MB231 tumor growth in nude mouse xenografts provided by ethyl acetate extract of

A. marina leaves elicited the suggestion that this extract may be useful in the treatment of breast cancer.

The polyisoprenoids extract from

A. marina leaves displayed weak cytotoxicity (IC50 value of 154.987 μg/mL) against WiDr colon cancer cells when compared with the standard doxorubicin (IC50 value of 5.445 μg/mL)

[9]. In addition, it was found that the mechanism underlying the cytotoxic effect of the extract was due to cell cycle inhibition and induction of apoptosis.

Yang et al.

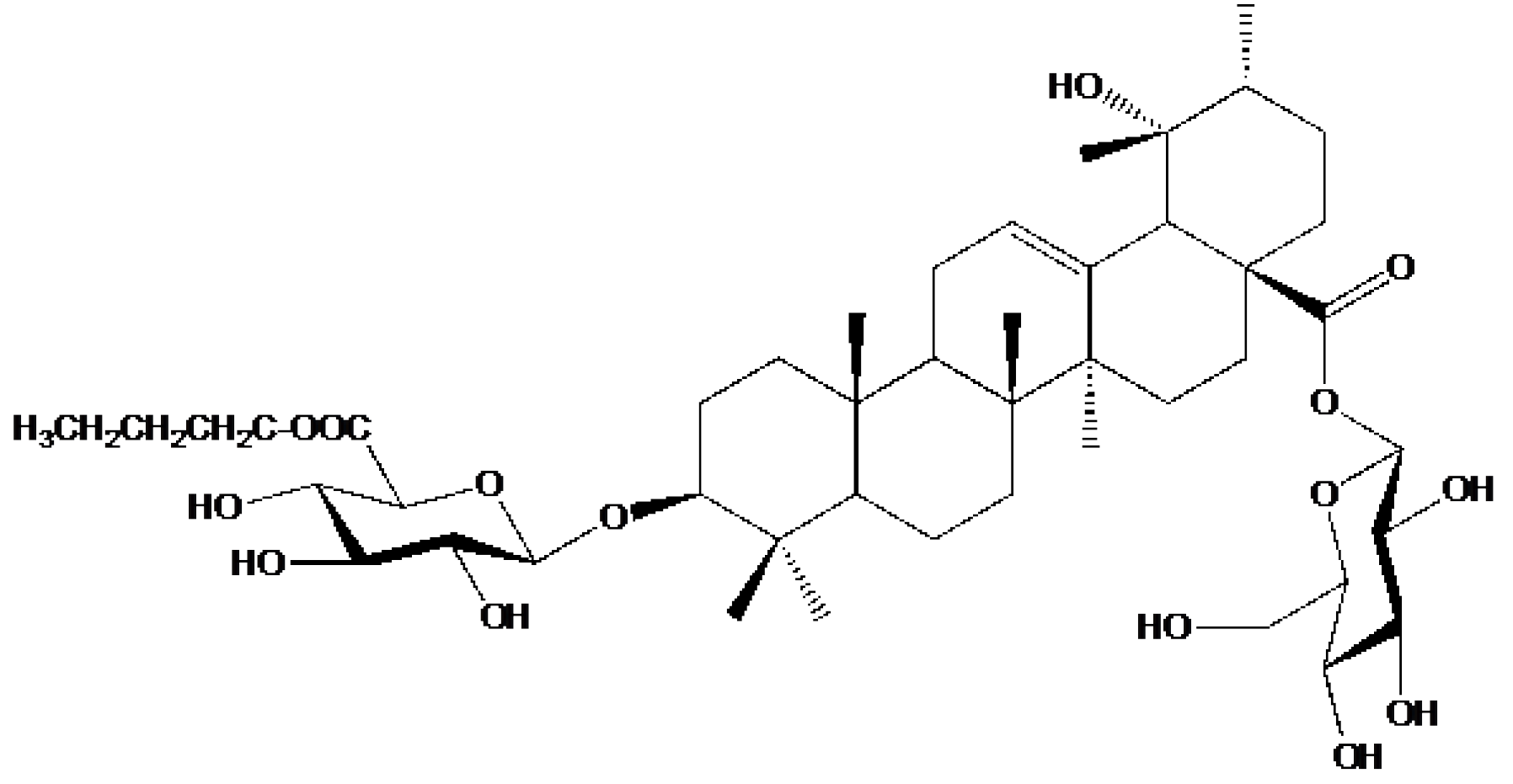

[10] isolated one new triterpenoid saponin, along with 29 known compounds, from the ethanol extract of

A. marina fruits. The new 6′-O-(n-butanol) ilekudinoside B ester (

Figure 1) was found to be cytotoxic against two human glioma stem cell lines, GSC-3# and GSC-18#, with IC50 values of 12.21 and 5.53 μg/mL, respectively.

Figure 1. Structure of 6′-O-(n-butanol) ilekudinoside B ester.

Qurrohman et al.

[11] extracted polyisoprenoids from n-hexane extract of

A. marina leaves. Polyisoprenoids exhibited cytotoxic activity against WiDr cells, with an IC50 value of 295.25 μg/mL, while the standard 5-FU had an IC50 value of 17.43 μg/mL. Cell cycle analysis revealed that the cell cicle inhibition of polyisoprenoids occurred in the G0-G1 phase. Furthermore, RT-PCR revealed that polyisoprenoids downregulated the P13k, Akt1, mTOR, and EGFR gene expression; however, they upregulated P53 gene expression.

The hexane extract of

A. marina leaves showed cytotoxic activity against human colon HCT-116, human liver HepG2, and human breast MCF-7 cancer cell lines, with IC50 values of 23.7 ± 0.7, 44.9 ± 0.93, and 79.55 ± 0.57 μg/mL, respectively, lower than those of the standard doxorubicin (IC50 values of 0.45 ± 0.052, 0.42 ± 0.10, and 0.6 ± 0.022 μg/mL, respectively). The study also revealed that hexane extract had a weak ability to induce apoptosis, although the cells showed membrane blebbings in addition to apoptotic bodies. Furthermore, it displayed inhibition of the cell cycle in the G0/G1 phase for HCT-116 cancer cells, and in the S phase for HepG2 and MCF-7 cell lines

[12].

The different acetone extracts of

A. marina leaves were prepared in a concentration range of 40–160 mg/mL, and the maximum cytotoxic activity against the liver HepG2 cancer cell line was observed at 120 mg/mL

[13].

Eldohaji et al.

[14] isolated lupeol, a pentacyclic triterpenoid, from hexane extract of

A. marina stems, clarifying its mechanism of anticancer action, since the data reported on lupeol were approximate and contradictory. The results indicated that lupeol caused considerable (

p < 0.001) growth inhibitory activity on breast MCF-7 (45%), resistant MCF-7 (46%), liver Hep3B (72%), and resistant Hep3B (35%) cancer cell lines, with slight toxic effects on normal fibroblast cells (F180). The mechanism of action of this triterpenoid was investigated by detecting its influence on key actors in cancer development and progression: BCL-2 anti-apoptotic and BAX pro-apoptotic proteins. They found that lupeol significantly (

p < 0.01) downregulated BCL-2 gene expression in parental and resistant Hep3B cells by 33 and 3.5 times, respectively, contributing to the induction of apoptosis in Hep3B cells, while no consequence of BAX was found. Proteins extracted from lupeol-treated Hep3B cells were analyzed by Western blot, which indicated the presence of activated caspase-3 cleaved by lupeol. Furthermore, as an indication of the absence of immune/inflammatory responses, the compound exhibited a negligible effect on the proliferation of monocytes, but caused an increase in the sub-G1 population and a reduction in the apoptosis rates of monocytes at 48 and 72 h.

Ethanolic extracts (400 μg/mL) of the lower half of pneumatophores, leaves, the upper half of pneumatophores, and shoots of

A. marina induced cell growth of 50% or more as well as inhibition of liver HepG2 cancer cells. Additionally, the leaf extract proved to be the most cytotoxic

[15].

Ethyl acetate extract from

A. marina roots contains a moderate quantity of phenolic compounds (yield, 2.48%) with no saponin detected in the sample, as well as a moderate amount of flavonoids (yield, 1.59%). The extract exhibited a cytotoxic effect on colorectal HT29, cervical HeLa, and breast T47D cancer cell lines, with IC50 values of 12.17, 22.76, and 163.61 μg/mL, while the positive control, cisplatin, displayed IC50 values of 115.91, 1.86, and 31.08, respectively. Moreover, the extract did not provide a cytotoxic effect against the normal cell line, hADSC

[16].

Afshar et al.

[17] evaluated the anticancer effects of ethanol and ethyl acetate extracts of

A. marina leaves. Phytochemical analysis revealed high phenolic and flavonoid contents, showing, for ethanol extract, 345 µg/mL gallic acid/0.01 g extract and 47.8 Mm GAE, and for ethyl acetate extract, 147.5 µg/mL gallic acid/0.01 g extract and 38.6 mM GAE. GC-MS analyses identified 60 compounds in the ethanol extract and 56 compounds in the ethyl acetate extract. The ethanol and ethyl acetate extracts exhibited cytotoxic activity on human breast cancer MCF-7 and human cervical HeLa cancer cells, with CC50 values of 70 and 102 µg/mL and 189 and 67 µg/mL, respectively. On the other hand, the extracts showed less activity against human ovarian carcinoma OVCAR3 cells (CC50 of 1087 and 272 µg/mL) and kidney epithelial Vero normal cells (382 and 242 µg/mL). Additionally, ethanol extract induced cell cycle arrest in the MCF-7 cancer cell line, while ethyl acetate extract caused apoptotic mechanisms in the OVCAR3 and HeLa cancer cell lines. Moreover, Western blot analysis demonstrated the increase in pro-apoptotic cell effectors, such as Bax and caspase-1, -3, and -7.

2. Avicennia marina Formulation to Improve the Anticancer Therapeutic Effect

The poor efficacy of many cancer treatments is often associated with the low targeting ratio of drugs, and to the side effects on healthy tissues, due to the aspecific distribution into other organs and tissues. Therefore, a much attention has been dedicated to the study of strategies to obtain a site-specific accumulation of therapeutic agents to the tumor region, avoiding side effects and toxicity

[18].

In this scenario, nanotechnology-based formulation is one of the most promising approaches exploited to overcome the bottlenecks of aspecific biodistribution, side effects, and low tumor accumulation

[19][20]. Nanoparticles (NPs) for drug delivery are carriers in the 1–1000 nm range, composed of different materials, including biocompatible and biodegradable natural/synthetic molecules, polymers, lipids, or metals. NPs are designed and developed to be loaded or covalently linked with bioactive molecules, such as proteins, peptides, antibodies, and nucleic acids, with the aim to: (1) overcome the problems associated with molecules’ solubility and in vivo bioavailability; (2) avoid the molecules’ degradation in the bloodstream; (3) improve the molecules’ targeting, internalization, and accumulation in the desired cells and tissues; (4) potentiate the drug’s effect.

[21] For these reasons, NPs are associated with plants and natural compounds to obtain a therapeutic, synergistic effect. Some papers have reported on the use of NPs to overcome the problems associated with the low tumor accumulation of

A. marina, aiming to improve its therapeutic effect.

Biogenic engineered silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) were synthesized from aqueous extract of

A. marina leaves by Varunkumar et al.

[22]. The resulting AgNPs displayed dose-dependent cytotoxic activity in the A549 lung cancer cell line (IC50 = 50 μg/mL), inducing ROS-mediated apoptosis, which was also confirmed by RT-PCR and Western blotting analysis. Both the p53-dependent and -independent caspase intermediated signaling pathways were demonstrated to be involved in the process. Tian et al.

[23] confirmed the anticancer property of synthesized AgNPs in A549 lung cancer cells; they observed a dose-dependent effect based on ROS activity, with an inhibition of 54% at the concentration of 50 µg/mL and 94% inhibition at 80 µg/mL.