Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Okanlawon Lekan Jolayemi | -- | 2857 | 2022-12-29 12:43:15 | | | |

| 2 | Rita Xu | -3 word(s) | 2854 | 2022-12-30 03:44:37 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Jolayemi, O.L.; Malik, A.H.; Ekblad, T.; Fredlund, K.; Olsson, M.E.; Johansson, E. Protein-Based Biostimulants. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/39583 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Jolayemi OL, Malik AH, Ekblad T, Fredlund K, Olsson ME, Johansson E. Protein-Based Biostimulants. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/39583. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Jolayemi, Okanlawon L., Ali H. Malik, Tobias Ekblad, Kenneth Fredlund, Marie E. Olsson, Eva Johansson. "Protein-Based Biostimulants" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/39583 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Jolayemi, O.L., Malik, A.H., Ekblad, T., Fredlund, K., Olsson, M.E., & Johansson, E. (2022, December 29). Protein-Based Biostimulants. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/39583

Jolayemi, Okanlawon L., et al. "Protein-Based Biostimulants." Encyclopedia. Web. 29 December, 2022.

Copy Citation

Protein-based biostimulants (PBBs) are derived from the hydrolysis of protein-rich raw materials of plant and/or animal origins, usually by-products or wastes from agro-industries. The active ingredients (AIs) produced by hydrolysis have the capacity to influence physiological and metabolic processes in plants, leading to enhanced growth, nutrient and water-use efficiency, tolerance to abiotic and biotic stresses, and improved crop yield and quality.

biostimulant

hydrolyzed wheat gluten

potato protein

sugar beet

1. Introduction to Biostimulants—Definition and Categories

Biostimulants are natural products that originate from plants, animals, or microorganisms and, when applied to plants (foliage or rhizosphere) in small quantities, stimulate natural processes that enhance growth, crop quality, nutrient-use efficiency, and tolerance to biotic and abiotic stresses [1][2][3][4][5][6][7]. Thus, the use of biostimulants can facilitate a reduced use of agrochemicals (especially fertilizers) in agriculture, without compromising crop productivity and quality, while also providing protection against abiotic and biotic stresses [1][3][8]. The use of biostimulants may not necessarily provide nutrients directly to plants or target pathogens, rather they regulate physiological processes that lead to enhanced growth and tolerance to abiotic and biotic stresses [2][3][5]. The current high use of agrochemicals in agriculture and food production poses risks to human health and the environment [1][2]. Biostimulants could form part of a solution to mitigate such risks deriving from the use of agrochemicals [8][9].

The use of biostimulants in commercial cropping settings is becoming increasingly popular, as the high content of bioactive components offers different benefits, whereas their mode of action is largely yet unknown [10]. They promote crop growth and reduce the impacts of agriculture on human health and the environment [10] and can thus be an important component in climate-smart agriculture (CSA) [7][11]. CSA is an approach that pushes for green and climate-resilient agri-food systems. Biostimulants are categorized into seaweed extracts, humic and fulvic acids, beneficial chemical elements (e.g., silicon, selenium, sodium, cobalt, aluminum), chitin and chitosan derivatives, beneficial microorganisms, inorganic salts (phosphite), and protein-based biostimulants (peptides and amino acids) [5][11][12].

The protein-based biostimulants (PBBs) are an important group because of the abundance and accessibility of protein-rich side-streams from agro-industries that can be used as raw materials for PBB production [13][14]. PBBs are commonly derived from individual organic materials or a combination of organic materials, most commonly obtained from agro-industries [15]. These industries often generate tons of waste and side-stream products, most of which have a high content of proteins and other bioactive compounds [3][13]. According to available statistics, the wastes generated annually by agriculture and agro-industries include 9000 tons of dairy protein [16], 3 million tons of seafood waste [17], and 8 million tons of livestock protein [18]. Converting these wastes into useful products, e.g., biostimulants, would thus address sustainability issues by contributing to a reduction in the environmental footprint, providing economic benefits from the use of novel products, and improving human and environmental health and food quality [3][9][19].

2. Protein-Based Biostimulants

2.1. Production

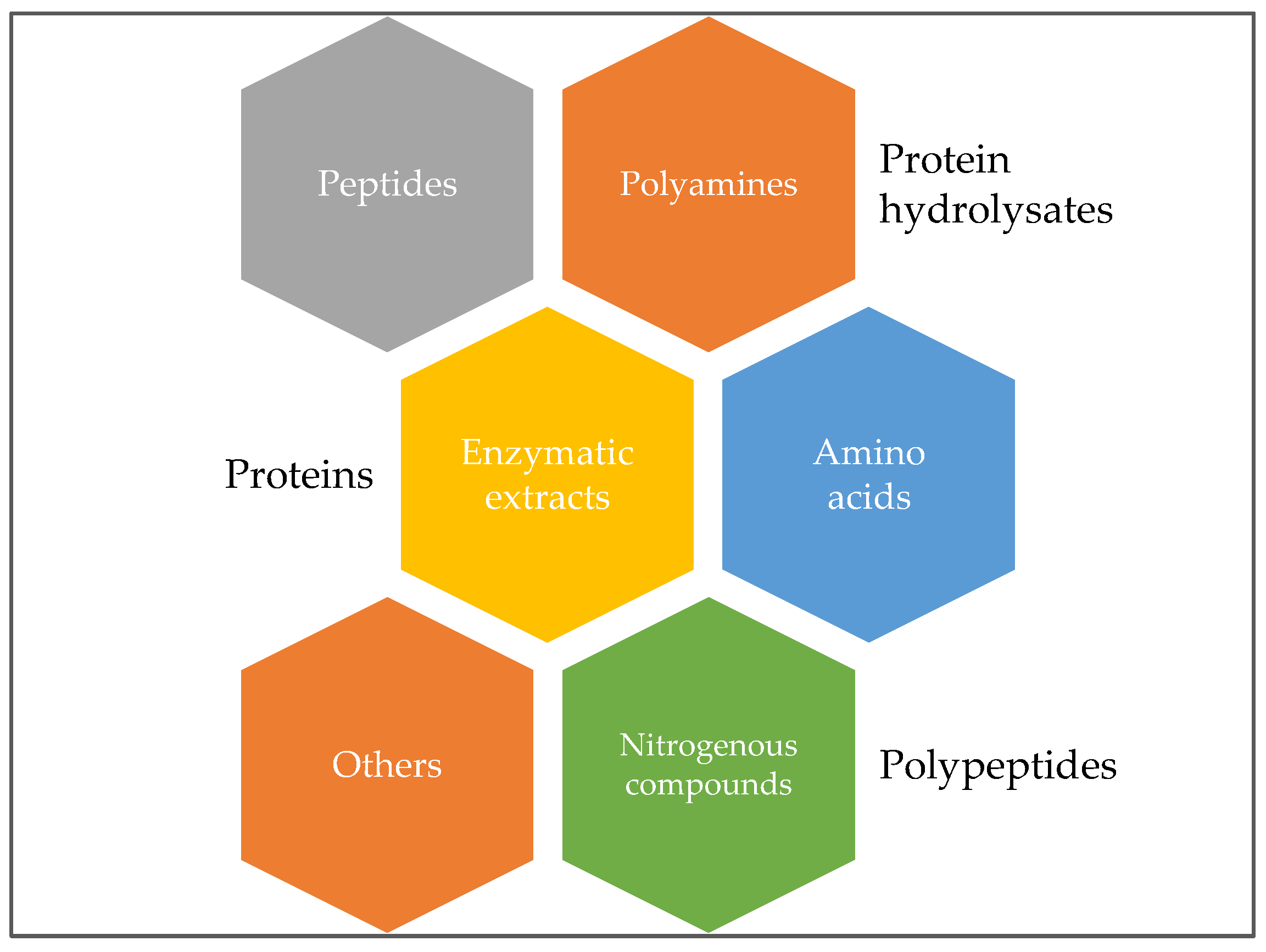

Protein-based biostimulants are basically mixtures of peptides and amino acids [2][20]. Most PBB products are derived from protein-rich substances (plant or animal origins) that have been enzymatically or chemically treated or subjected to thermal hydrolysis. The products are, therefore, often referred to as protein hydrolysates (PHs) [2][3][11][21]. They contain peptides and free essential and non-essential amino acids present in different quantities, depending on the protein source, processing methods utilized and degree of hydrolysis [2][13] (Figure 1). The active ingredients (peptides and amino acids) in the PHs, contribute to an increased uptake of beneficial elements into plant tissues via the leaves or roots [3][11]. Currently, more than 90% of commercially available PHs are derived from chemical hydrolysis of animal proteins, e.g., collagen, fish by-products, blood meal, chicken feathers, etc. [20][22]. Commercially available animal-derived PH products include Siapton [3], Pepton [23], and Hydrostim [24]. However, there are restrictions on the use of PBBs derived from animal by-products in the European Union (EU), where animal-derived products can only be used as raw material for biostimulants at the endpoint of the manufacturing chain, and with a particular focus on the safety of humans, animals, and the environment [25]. Under current EU regulations, biostimulants from animal-derived products may also not be applied directly to edible plant parts and the maximum concentration of heavy metals must be non-detectable [25]. Sweden, as an EU country, is following EU regulations. Commercial plant-derived PHs, e.g., Coveron [26] and Trainer [21], are also available in different forms (liquid, water-soluble powder, granules) and can be applied as foliar spray, seed, root, or soil treatments [11][22]. However, plant biostimulants are a recently emerging field of research with an increasing number of publications from 2015 and onwards [5] and the research on PBBs and PHs is keeping track of that development [2][3][4]. As an increasing number of commercial plant- and animal protein-based biostimulants will enter the market as a result of the increasing research activities, additional regulations on the use of the products are expected.

Figure 1. Possible active ingredients in protein-based biostimulants (PBBs). Compounds in white and black are large molecules, while active ingredients in colored hexagons are low molecular weight components of proteins [27].

2.2. Effects of PBBs on Soil and on Agronomic, Physiological, and Molecular Plant Parameters

Research on PBBs and their commercial use in agricultural and horticultural applications are of a rather recent origin, with most development having taken place during the past two decades [11]. Most of the PBBs evaluated to date have been shown to have a broad-spectrum effect on the biochemical properties and microbial community of the soil. They have also been found to have a significant effect on plant growth and health, as summarized in Table 1. As a result, PBBs have been used in soil bioremediation activities, for soil restoration, and for preventing soil erosion [28]. Studies have indicated that a high nitrogen content (>50%) and a high percentage (>60%) of peptides with low molecular weight (<3 kDa) are beneficial in PBBs used as an amendment to semi-arid soil [28].

Furthermore, PBBs have a positive impact on the metabolic processes of plants, as they enhance root and shoot growth, photosynthesis rate, and crop quality [3][12][22][29][30]. PBBs are reported to regulate biochemical processes that boost the tolerance of crops against abiotic stresses (drought, salinity, and heavy metals) [12]. They have also been found to stimulate nutrient uptake and nutrient use efficiency in crops, largely due to their growth-enhancing effects on roots [12]. In addition, PBBs can have indirect effects on plants by enhancing uptake and efficient use of macro- and micronutrients [12][30]. Most biostimulating effects have been linked to the presence of soluble peptides and free amino acids in PHs, which in many cases, act as precursors for the biosynthesis of phytohormones (plant-growth regulators) and other metabolically important bioactive compounds which then contribute to the plant-growth enhancement [3][8][22]. These soluble peptides and free amino acids are easily absorbed by soil microorganisms, which helps to improve soil structure, soil organic matter content, and nutrient availability [28].

Enhanced shoot and root growth have been reported, e.g., in kiwi and snapdragon plants to which PBBs were applied at a low dosage [26][31][32]. Increased coleoptile length in maize has been reported, although a relatively high concentration of PBBs was needed to obtain that effect [11]. Soy PBB incorporated into broccoli seed pellets has been found to enhance plant height [6]. Similarly, enhanced plant height and plant canopy area have been obtained in maize [33] and tomato [34] through the use of PBBs. Moreover, the use of PBBs has been found to enhance the biomass production of broccoli, maize, lettuce [6][30][35], banana, and rocket [36][37]. In one study, plant height and total biomass of hibiscus plants were increased by applying PBBs from two urban biowaste materials [38].

In addition to the effect on plant growth, PBBs have been found to be involved in several molecular and physiological processes in plants [12]. For example, the nitrogen content in maize and cucumber plants has been found to be increased by treatment with plant-derived PHs and hydrolyzed collagen, respectively [39][40]. Furthermore, PBB treatment of maize has been shown to induce the secretion of enzymes involved in carbon and nitrogen metabolism [33][41].

Several studies have demonstrated that PBBs can improve crop tolerance to abiotic stresses [22], e.g., calcium protein hydrolysate has been found to reduce chloride uptake in Oriental persimmon (Diospyros kaki L.) [42]. Furthermore, gelatin-treated cucumber plants have been shown to exhibit higher salinity tolerance than untreated plants [43], while the foliar application of PH to lettuce can enhance the tolerance to low temperatures [44]. Paul et al. [45] observed an increased growth in tomatoes treated with PHs under drought stress. Others have observed a reduction in anti-nutritional content (nitrate) in leaves of lettuce treated with PH (both foliar and root application) compared with untreated plants [46]. The ability of plants to tolerate abiotic stresses following PH treatment has been attributed to genes being induced that contribute to enhanced growth, improved nutrient status, greater cell structure stability, osmolite and antioxidant accumulation, and enzyme activation by PHs [22].

Generally, the effect of PBBs depends on the source and characteristics of the PBB, the crop (species and cultivars) on which the PBB is utilized, the age or growth stage of the crop, growing conditions, PBB concentration, timing and mode of application (soil, seed, or foliar treatment), PBB solubility, and leaf permeability [22].

There have only been a few comparative studies on the efficiency of PBBs and other categories of biostimulants and chemical fertilizers [47][48][49][50]. One major principle of biostimulants is that they help to reduce the quantity of fertilizer required, rather than replacing chemical fertilizers [51]. Dudas [47] achieved enhanced growth and biochemical concentrations in lettuce by using biostimulants and fertilizer, compared with an untreated control. The specific effects of PBBs and other categories of biostimulants are largely based on the different bioactive components present in their molecules [49][50][52]. These specific effects include the enhancement of antioxidant content, antibiotic effect, abiotic tolerance, etc. [20]. The comparative efficiency of different categories of biostimulants in relation to chemical fertilizers can be established using different omics approaches [53].

Table 1. Reported effect on crop performance of different protein hydrolysates (PHs) used as protein-based biostimulants (PBBs).

| SN | PBB | Effect | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PH, plant source | Improves yield and quality of perennial wall rocket | Caruso et al. [21] https://www.mdpi.com/2223-7747/8/7/208 Accessed 23 July 2022 |

| 2 | PH, plant source | Enhances plant physiology and stimulates soil microbiome | Colla et al. [22] https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpls.2017.02202 Accessed 23 July 2022 |

| 3 | PH, animal source (Pepton) | Improves salicylic acid and growth of tomato roots under abiotic stress | Casadesus et al. [23] https://www.mdpi.com/2223-7747/8/7/208 Accessed 23 July 2022 |

| 4 | PH, animal source | Improves growth and microelement concentration in hydroponically grown maize | Ertani et al. [31] https://doi.org/10.1002/jpln.201200020 Accessed 23 July 2022 |

| 5 | PH, plant source | Enhances growth and nitrogen metabolism of maize | Ertani et al. [33] https://doi.org/10.1002/jpln.200800174 Accessed 23 July 2022 |

| 6 | PH, plant source | Improves agronomic, physiological and yield parameters of baby rocket plant | Di-Mola et al. [37] https://doi.org/10.3390/plants8110522 Accessed 23 July 2022 |

| 7 | PH, plant source (Trainer) | Improves performance of maize and lettuce | Colla et al. [39] https://doi.org/10.17660/ActaHortic.2013.1009.21 Accessed 23 July 2022 |

| 8 | PH, animal source (gelatin) | Improves plant performance | Wilson et al. [40] https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpls.2018.01006 Accessed 23 July 2022 |

| 9 | PH, plant source | Enhances gene expression, enzymes and nitrogen metabolism in maize | Schiavon et al. [41] https://doi.org/10.1021/jf802362g Accessed 23 July 2022 |

| 10 | Calcium, PH | Improves salinity tolerance and leaf necrosis in Diospyros kaki L. | Visconti et al. [42] https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2015.01.028 Accessed 23 July 2022 |

2.3. Social, Economic, and Environmental Aspects of PBBs

Through their direct and indirect effects on crop yield and quality, nutrient-use efficiency, and tolerance to biotic and abiotic stresses, PBBs have the potential to contribute to socioeconomic development [54][55][56]. First, the production and use of protein-rich side-streams from agro-industries create novel jobs and novel products, which in turn provide novel income opportunities [54]. The sustainable use of more side-streams from agro-industries contributes to (i) social development in societies involved in the business, (ii) economic development and growth through product development, and (iii) environmental benefits from more complete use of natural resources [56]. Farm income is increased due to increases in crop yield and quality resulting from use of PBBs [56][57]. Economic benefits from the use of plant-based biostimulants, due to the increase in the yield have been reported for a range of crops, including perennial wall rocket and lamb’s lettuce [58][59]. However, the economic return of using plant side-streams for additional products is always decreasing as soon as an extra harvesting or processing step is introduced into their production [57]. Thus, a benefit of using PBBs from side streams of the food industry (e.g., wheat gluten or potato protein) is that these substances are readily available at a reasonable price from the industry [14]. Furthermore, the use of PBBs may lead to the production of healthier crops and more nutritious food, which will enhance the health of consumers [56]. PBBs might improve land-use efficiency by enhancing crop yield, quality, and profitability per acre [60].

The economic efficiency of various types of biostimulants has been limitedly evaluated. Most studies report a certain increase in crop yield or plant development, often given in % of increase as related to a control treatment. For PBBs, the comparison of effects between different types or to other types of biostimulants, e.g., other biological, chemical or fertilizer compounds, is mainly lacking; although, a high effect has been reported in few studies [61].

The use of PBBs may also lead to the production of healthier crops and more nutritious food, improving consumer health [56]. Additionally, PBBs may improve land use efficiency by enhancing crop yield, quality, and profitability per acre [58].

The use of biostimulants has been proven to have positive effects on the environment by improving the nutrient-use efficiency of crops, thereby reducing the quantities of agrochemicals needed in food production by up to 50% [3][4]. PBBs also improve soil health, by boosting the communities of beneficial soil microorganisms present [54] and by strengthening soil structure and increasing soil water-holding capacity, thus preventing soil erosion [55]. The small quantity of biostimulants required for crop growth and development improvements means that there are no residues left in crops and soil [2][37]. There is, thus, a limited risk of PBBs causing environmental problems in food, soil, or water bodies [2][37][62][63][64][65][66]. The fact that most PBBs are highly biodegradable also results in the safety of life on land and in water [3][9]. Thus, the use of PBBs could result in improved surface water quality and lower carbon emissions [29].

The recycling and conversion of protein-rich wastes or side streams products from agriculture and agro-allied industries into PBBs, pave the way for a more resilient use of natural resources [3][67][68][69][70][71]. The food industry is one of the major contributors to greenhouse gas emissions contributing to climate change, and the increased use of side streams from food production is seen as important to mitigate climate change [68]. This leads to a strong focus in the plant biologicals industries to continue to develop novel natural active ingredients (biostimulants) from agro-industrial wastes [70].

3. Hydrolyzed Wheat Gluten (HWG) and Potato Protein (PP) as Possible PBBs

3.1. Hydrolyzed Wheat Gluten (HWG)

Wheat gluten is defined as the rubbery mass of proteins, obtained when wheat flour is washed with water to remove starch and other water-soluble components [72][73][74]. Wheat gluten is available in large quantities and at low cost as a result of large-scale industrial starch extraction from wheat flour [71][72][73][74][75][76][77][78][79][80]. Some industrially produced gluten is used as a co-product for several purposes, e.g., within the baking industry [78]. However, the quantities of wheat gluten produced leave much scope for additional uses [72][81][82][83]. To increase the applicability of wheat gluten, structural modification to enhance its functional properties is often required [71][72], as it is highly polymerized in its native state [14][74][77][81]. The most common way to modify its structure is by enzymatic or thermal treatment or chemical hydrolysis, or a combination of these processes [71][72][78].

Like many other plant PHs, HWG has a wide set of applications in the food industry, particularly as an ingredient since it resembles glutamate in terms of taste [71][78]. As HWG is a hydrolyzed protein-rich co-stream from starch production, it most likely (based on the above discussion) has properties that make it suitable as a biostimulant within agriculture and horticulture [72]. However, to the knowledge, HWG has, until now, not been evaluated as a source to be used in agricultural applications. Similar to other PHs (biostimulants), the hydrolysis of wheat gluten results in a breakdown of the protein into peptides and a large amount of free amino acids, which are beneficial for plant growth and health [71][76][77][78][79][80].

3.2. Potato Protein (PP)

Potato fruit juice (PFJ) is a massive protein-rich side-stream generated in starch extraction from potatoes [14]. In 2018, the amount of PFJ obtained after starch extraction represented around ~1% (3.5 million tons) of the total global potato production (>360 million tons) [81][84][85]. In the past, PFJ was regarded as waste and was released into nearby streams and other water bodies, resulting in environmental pollution [82][83]. However, potato protein (PP) is a potentially valuable product that can be produced from PFJ through acidification and harsh thermal processing [14][86]. These processes result in intensive coagulation and protein recovery [14][82]. In theory, a total of 200,000 tons of PP could be generated from the 3.5 million tons of PFJ made available annually worldwide [73][79]. Some studies have indicated that PP is one of the largest under-utilized agro-industrial protein-rich side-streams in the world [14]. PP has the potential to act as a ready source of organic nitrogen for crops, as the protein content of PP is >80% [14]. A sustainable way of using PP would be through its application as a PBB. PP has been limitedly evaluated for its use in agriculture, although, trials to use it as a functional food component are ongoing [87][88].

References

- Ertani, A.; Pizzeghello, D.; Francioso, O.; Sambo, P.; Sanchez-Cortes, S.; Nardi, S. Capsicum chinensis L. growth and nutraceutical properties are enhanced by biostimulants in a long-term period: Chemical and metabolomic approaches. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 375.

- Nardi, S.; Pizzeghello, D.; Schiavon, M.; Ertani, A. Plant biostimulants: Physiological responses induced by protein hydrolyzed-based products and humic substances in plant metabolism. Sci. Agric. 2016, 73, 18–23.

- Moreno-Hernández, J.M.; Benítez-García, I.; Mazorra-Manzano, M.A.; Ramírez-Suárez, J.C.; Sánchez, E. Strategies for production, characterization and application of protein-based biostimulants in agri-culture: A review. Chil. J. Agric. Res. 2020, 80, 274–289.

- Brown, P.H.; Saa, S. Biostimulants in agriculture. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 671.

- Du Jardin, P. Plant biostimulants: Definition, concept, main categories and regulation. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 196, 3–14.

- Amirkhani, M.; Netravali, A.N.; Huang, W.; Taylor, A.G. Investigation of soy protein–based biostimulant seed coating for broccoli seedling and plant growth enhancement. HortScience 2016, 51, 1121–1126.

- The European Biostimulants Industry Council (EBIC). 2020. Available online: https://biostimulants.eu (accessed on 14 December 2021).

- de Vasconcelos, A.C.F.; Chaves, L.H.G. Biostimulants and Their Role in Improving Plant Growth under Abiotic Stresses. In Biostimulants in Plant Science; Mirmajlessi, S.M., Radhakrishnan, R., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019.

- Ogunsanya, H.Y.; Motti, P.; Li, J.; Trinh, H.K.; Xu, L.; Bernaert, N.; Van Droogenbroeck, B.; Murvanidze, N.; Werbrouck, S.P.O.; Mangelinckx, S.; et al. Belgian endive-derived biostimulants promote shoot and root growth in vitro. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 8792.

- Ayed, S.; Bouhaouel, I.; Jebari, H.; Hamada, W. Use of Biostimulants: Towards Sustainable Ap-proach to Enhance Durum Wheat Performances. Plants 2022, 11, 133.

- Colla, G.; Rouphael, Y.; Lucini, L.; Canaguier, R.; Stefanoni, W.; Fiorillo, A.; Cardarelli, M. Protein hydrolysate-based biostimulants: Origin, biological activity and application methods. In Proceedings of the II World Congress on the Use of Biostimulants in Agriculture, Florence, Italy, 16–19 November 2015; p. 1148.

- Rouphael, Y.; Colla, G. Editorial: Biostimulants in Agriculture. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 40.

- Jorobekova, S.; Kydralieva, K. Plant Growth Biostimulants from By-Products of Anaerobic Digestion of Organic Substances. In Organic Fertilizers—History, Production and Applications; Larramendy, M., Soloneski, S., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019.

- Capezza, A.J.; Muneer, F.; Prade, T.; Newson, W.R.; Das, O.; Lundman, M.; Olsson, R.T.; Hedenqvist, M.S.; Johansson, E. Acylation of agricultural protein biomass yields biodegradable superabsorbent plastics. Commun. Chem. 2021, 4, 52.

- Xu, L.; Geelen, D. Developing Biostimulants From Agro-Food and Industrial By-Products. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1567.

- Rajarajan, G.; Irshad, A.; Raghunath, B.V.; Kumar, G.M.; Punnagaiarasi, A. Utilization of Cheese Industry Whey for Biofuel–Ethanol Production. In Integrated Waste Management in India; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 59–64.

- Ferraro, V.; Cruz, I.B.; Jorge, R.F.; Malcata, F.X.; Pintado, M.E.; Castro, P.M. Valorisation of nat-ural extracts from marine source focused on marine by-products: A review. Food Res. Int. 2010, 43, 2221–2233.

- Martínez-Alvarez, O.; Chamorro, S.; Brenes, A. Protein hydrolysates from animal processing by-products as a source of bioactive molecules with interest in animal feeding: A review. Food Res. Int. 2015, 73, 204–212.

- Ali, O.; Ramsubhag, A.; Jayaraman, J. Biostimulant properties of seaweed extracts in plants: Im-plications towards sustainable crop production. Plants 2021, 10, 531.

- Colla, G.; Nardi, S.; Cardarelli, M.; Ertani, A.; Lucini, L.; Canaguier, R.; Rouphael, Y. Protein hydrolysates as biostimulants in horticulture. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 196, 28–38.

- Caruso, G.; De Pascale, S.; Cozzolino, E.; Giordano, M.; El-Nakhel, C.; Cuciniello, A.; Cenvinzo, V.; Colla, G.; Rouphael, Y. Protein Hydrolysate or Plant Extract-based Biostimulants Enhanced Yield and Qual-ity Performances of Greenhouse Perennial Wall Rocket Grown in Different Seasons. Plants 2019, 8, 208. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2223-7747/8/7/208 (accessed on 23 July 2022).

- Colla, G.; Hoagland, L.; Ruzzi, M.; Cardarelli, M.; Bonini, P.; Canaguier, R.; Rouphael, Y. Biostimulant Action of Protein Hydrolysates: Unraveling Their Effects on Plant Physiology and Microbiome. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 2202.

- Casadesús, A.; Pérez-Llorca, M.; Munné-Bosch, S.; Polo, J. An Enzymatically Hydrolyzed Animal Protein-Based Biostimulant (Pepton) Increases Salicylic Acid and Promotes Growth of Tomato Roots Under Temperature and Nutrient Stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 953.

- Cristiano, G.; Pallozzi, E.; Conversa, G.; Tufarelli, V.; De Lucia, B. Effects of an animal-derived bi-ostimulant on the growth and physiological parameters of potted snapdragon (Antirrhinum majus L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 861.

- The European Commission. Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) No 354/2014 of 8 April 2014. Official Journal of the European Union. 2014. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32014R0354&from=EN (accessed on 23 July 2022).

- Rouphael, Y.; Lucini, L.; Miras-Moreno, B.; Colla, G.; Bonini, P.; Cardarelli, M. Metabolomic re-sponses of maize shoots and roots elicited by combinatorial seed treatments with microbial and non-microbial biostimulants. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 664.

- Agricen Sciences. Analysis of Market Analysts, Survey Papers on Biostimulants. 2021. Available online: BPIA.com (accessed on 21 September 2021).

- Tejada, M.; Benítez, C.; Gómez, I.; Parrado, J. Use of biostimulants on soil restoration: Effects on soil biochemical properties and microbial community. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2011, 49, 11–17.

- Hamedani, S.R.; Rouphael, Y.; Colla, G.; Colantoni, A.; Cardarelli, M. Biostimulants as a Tool for Improving Environmental Sustainability of Greenhouse Vegetable Crops. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5101.

- Colla, G.; Rouphael, Y. Biostimulants in horticulture. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 196, 1–134.

- Ertani, A.; Pizzeghello, D.; Altissimo, A.; Nardi, S. Use of meat hydrolyzate derived from tanning residues as plant biostimulant for hydroponically grown maize. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2013, 176, 287–295.

- Qurartieri, M.; Lucchi, A.; Cavani, L. Effects of the rate of protein hydrolysis and spray concentra-tion on growth of potted kiwifruit (Actinidia deliciosa) plants. Acta Hortic. 2002, 594, 341–347.

- Ertani, A.; Cavani, L.; Pizzeghello, D.; Brandellero, E.; Altissimo, A.; Ciavatta, C.; Nardi, S. Biostimulant activity of two protein hydrolyzates in the growth and nitrogen metabolism of maize seedlings. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2009, 172, 237–244.

- Parrado, J.; Bautista, J.; Romero, E.; García-Martínez, A.; Friaza, V.; Tejada, M. Production of a carob enzymatic extract: Potential use as a biofertilizer. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 2312–2318.

- Lucini, L.; Rouphael, Y.; Cardarelli, M.; Canaguier, R.; Kumar, P.; Colla, G. The effect of a plant-derived biostimulant on metabolic profiling and crop performance of lettuce grown under saline con-ditions. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 182, 124–133.

- Gurav, R.G.; Jadhav, J.P. A novel source of biofertilizer from feather biomass for banana cultiva-tion. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2013, 20, 4532–4539.

- Di Mola, I.; Ottaiano, L.; Cozzolino, E.; Senatore, M.; Giordano, M.; El-Nakhel, C.; Sacco, A.; Rouphael, Y.; Colla, G.; Mori, M. Plant-based biostimulants influence the agronomical, physiological, and quali-tative responses of baby rocket leaves under diverse nitrogen conditions. Plants 2019, 8, 522.

- Massa, D.; Prisa, D.; Montoneri, E.; Battaglini, D.; Ginepro, M.; Negre, M.; Burchi, G. Application of municipal biowaste derived products in Hibiscus cultivation: Effect on leaf gaseous exchange activity, and plant biomass accumulation and quality. Sci. Hortic. 2016, 205, 59–69.

- Planques, B.; Colla, G.; Svecová, E.; Cardarelli, M.; Rouphael, Y.; Reynaud, H.; Canaguier, R. Effectiveness of a plant-derived protein hydrolysate to improve crop performances under different growing conditions. In I World Congress on the Use of Biostimulants in Agriculture 1009; International Society for Horticultural Science: Leuven, Belgium, 2012; pp. 175–179.

- Wilson, H.T.; Amirkhani, M.; Taylor, A.G. Evaluation of Gelatin as a Biostimulant Seed Treatment to Improve Plant Performance. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1006.

- Schiavon, M.; Ertani, A.; Nardi, S. Effects of an Alfalfa Protein Hydrolysate on the Gene Expression and Activity of Enzymes of the Tricarboxylic Acid (TCA) Cycle and Nitrogen Metabolism in Zea mays L. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 11800–11808.

- Visconti, F.; de Paz, J.M.; Bonet, L.; Jordà, M.; Quiñones, A.; Intrigliolo, D.S. Effects of a commercial calcium protein hydrolysate on the salt tolerance of Diospyros kaki L. cv. “Rojo Brillante” grafted on Diospyros lotus L. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 185, 129–138.

- Wilson, H. Gelatin, a Biostimulant Seed Treatment and Its Impact on Plant Growth, Abiotic Stress, and Gene Regulation. Ph.D. Dissertation, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA, 2015; p. 217.

- Botta, A. Enhancing plant tolerance to temperature stress with amino acids: An approach to their mode of action. In Proceedings of the I World Congress on the Use of Biostimulants in Agriculture, Strasbourg, France, 26–29 November 2012; p. 1009.

- Paul, K.; Sorrentino, M.; Lucini, L.; Rouphael, Y.; Cardarelli, M.; Bonini, P.; Reynaud, H.; Canaguier, R.; Trtílek, M.; Panzarová, K. Understanding the biostimulant action of vegetal-derived protein hy-drolysates by high-throughput plant phenotyping and metabolomics: A case study on tomato. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 47.

- Tsouvaltzis, P.; Koukounaras, A.; Siomos, A.S. Application of amino acids improves lettuce crop uniformity and inhibits nitrate accumulation induced by the supplemental inorganic nitrogen fertilization. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 2014, 16, 951–955.

- Dudaš, S.; Šola, I.; Sladonja, B.; Erhatić, R.; Ban, D.; Poljuha, D. The Effect of Biostimulant and Fertilizer on “Low Input” Lettuce Production. Acta Bot. Croat. 2016, 75, 253–259.

- Benito, P.; Ligorio, D.; Bellón, J.; Yenush, L.; Mulet, J.M. A fast method to evaluate in a combinatorial manner the synergistic effect of different biostimulants for promoting growth or tolerance against abiotic stress. Plant Methods 2022, 18, 111.

- Halpern, M.; Bar-Tal, A.; Ofek, M.; Minz, D.; Muller, T.; Yermiyahu, U. Chapter Two—The Use of Biostimulants for Enhancing Nutrient Uptake. In Advances in Agronomy; Sparks, D.L., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015; Volume 130, pp. 141–174.

- Bhupenchandra, I.; Chongtham, S.K.; Devi, E.L.; Ramesh, R.; Choudhary, A.K.; Salam, M.D.; Sahoo, M.R.; Bhutia, T.L.; Devi, S.H.; Thounaojam, A.S.; et al. Role of biostimulants in mitigating the effects of climate change on crop performance. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 967665.

- Berlyn, G.P.; Sivaramakrishnan, S. The Use of Organic Biostimulants to Reduce Fertilizer Use, In-Crease Stress Resistance, and Promote Growth. In Tech. Coords. National Proceedings, Forest and Conservation Nursery Associations. Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW-GTR-389; Landis, T.D., South, D.B., Eds.; United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service General Technical Report PNW: Portland, OR, USA, 1997; pp. 106–112.

- Abd-Elkader, D.Y.; Mohamed, A.A.; Feleafel, M.N.; Al-Huqail, A.A.; Salem, M.Z.M.; Ali, H.M.; Hassan, H.S. Photosynthetic Pigments and Biochemical Response of Zucchini (Cucurbita pepo L.) to Plant-Derived Extracts, Microbial, and Potassium Silicate as Biostimulants Under Greenhouse Conditions. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 879545.

- Rouphael, Y.; Colla, G. Toward a Sustainable Agriculture Through Plant Biostimulants: From Ex-perimental Data to Practical Applications. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1461. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4395/10/10/1461 (accessed on 23 July 2022).

- Wezel, A.; Casagrande, M.; Celette, F.; Vian, J.-F.; Ferrer, A.; Peigné, J. Agroecological practices for sustainable agriculture. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 34, 1–20.

- Abou Chehade, L.; Al Chami, Z.; De Pascali, S.A.; Cavoski, I.; Fanizzi, F.P. Biostimulants from food processing by-products: Agronomic, quality and metabolic impacts on organic tomato (Solanum lyco-persicum L.). J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 98, 1426–1436.

- Kocira, S.; Szparaga, A.; Hara, P.; Treder, K.; Findura, P.; Bartoš, P.; Filip, M. Biochemical and economical effect of application biostimulants containing seaweed extracts and amino acids as an element of agroecological management of bean cultivation. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 17759.

- Prade, T.; Muneer, F.; Berndtsson, E.; Nynäs, A.-L.; Svensson, S.-E.; Newson, W.R.; Johansson, E. Protein fractionation of broccoli (Brassica oleracea, var. Italica) and kale (Brassica oleracea, var. Sabellica) residual leaves—A pre-feasibility assessment and evaluation of fraction phenol and fibre content. Food Bioprod. Process. 2021, 130, 229–243.

- Giordano, M.; El-Nakhel, C.; Caruso, G.; Cozzolino, E.; De Pascale, S.; Kyriacou, M.C.; Colla, G.; Rouphael, Y. Stand-Alone and Combinatorial Effects of Plant-based Biostimulants on the Production and Leaf Quality of Perennial Wall Rocket. Plants 2020, 9, 922.

- Di Mola, I.; Cozzolino, E.; Ottaiano, L.; Nocerino, S.; Rouphael, Y.; Colla, G.; Mori, M. Nitrogen use and uptake efficiency and crop performance of baby spinach (Spinacia oleracea L.) and Lamb’s Lettuce (Valerianella locusta L.) grown under variable sub-optimal N regimes combined with plant-based biostim-ulant application. Agronomy 2020, 10, 278.

- Nordqvist, P.; Johansson, E.; Khabbaz, F.; Malmström, E. Characterization of hydrolyzed or heat treated wheat gluten by SE-HPLC and 13C NMR: Correlation with wood bonding performance. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2013, 51, 51–61.

- Jolayemi, O.L.; Malik, A.H.; Ekblad, T.; Olsson, M.E.; Johansson, E. Protein-Based Biostimulants Enhanced Early Growth and Establishment of Sugar Beet. Res. Sq. 2021, preprint.

- Goulding, K. Nitrate leaching from arable and horticultural land. Soil Use Manag. 2006, 16, 145–151.

- Sutton, M.A.; Bleeker, A.; Howard, C.; Erisman, J.; Abrol, Y.; Bekunda, M.; Datta, A.; Davidson, E.; De Vries, W.; Oenema, O. Our Nutrient World. The Challenge to Produce More Food & Energy with Less Pollution; Centre for Ecology & Hydrology: Wallingford, UK, 2013; Available online: https://library.wur.nl/WebQuery/wurpubs/reports/434951 (accessed on 23 July 2022).

- Lassaletta, L.; Billen, G.; Grizzetti, B.; Anglade, J.; Garnier, J. 50-year trends in nitrogen use effi-ciency of world cropping systems: The relationship between yield and nitrogen input to cropland. Environ. Res. Lett. 2014, 9, 105011.

- Gupta, R.B.; Khan, K.; Macritchie, F. Biochemical Basis of Flour Properties in Bread Wheats. I. Effects of Variation in the Quantity and Size Distribution of Polymeric Protein. J. Cereal Sci. 1993, 18, 23–41.

- Lu, C.; Tian, H. Global nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizer use for agriculture production in the past half century: Shifted hot spots and nutrient imbalance. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2017, 9, 181–192.

- Malik, A.; Mor, V.; Tokas, J.; Punia, H.; Malik, S.; Malik, K.; Sangwan, S.; Tomar, S.; Singh, P.; Singh, N.; et al. Biostimulant-Treated Seedlings under Sustainable Agriculture: A Global Perspective Facing Climate Change. Agronomy 2020, 11, 14.

- Puglia, D.; Pezzolla, D.; Gigliotti, G.; Torre, L.; Bartucca, M.; Del Buono, D. The Opportunity of Valorizing Agricultural Waste, Through Its Conversion into Biostimulants, Biofertilizers, and Biopolymers. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2710.

- Van Oosten, M.J.; Pepe, O.; De Pascale, S.; Silletti, S.; Maggio, A. The role of biostimulants and bio-effectors as alleviators of abiotic stress in crop plants. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2017, 4, 5.

- Biological Products Industry Alliance. Biostimulant Resource Deck. 2018. Available online: www.bpia.com (accessed on 23 July 2022).

- Asrarkulova, A.S.; Bulushova, N.V. Wheat Gluten and Its Hydrolysates. Possible Fields of Practical Use. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2018, 54, 825–833.

- Kong, X.; Zhou, H.; Qian, H. Enzymatic hydrolysis of wheat gluten by proteases and properties of the resulting hydrolysates. Food Chem. 2007, 102, 759–763.

- Wookey, N. Wheat gluten as a protein ingredient. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 1979, 56, 306–309.

- Markgren, J.; Hedenqvist, M.; Rasheed, F.; Skepö, M.; Johansson, E. Glutenin and Gliadin, a Piece in the Puzzle of their Structural Properties in the Cell Described through Monte Carlo Simulations. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1095.

- Rombouts, I.; Lagrain, B.; Delcour, J.A.; Türe, H.; Hedenqvist, M.S.; Johansson, E.; Kuktaite, R. Crosslinks in wheat gluten films with hexagonal close-packed protein structures. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2013, 51, 229–235.

- Capezza, A.J.; Lundman, M.; Olsson, R.T.; Newson, W.R.; Hedenqvist, M.S.; Johansson, E. Carboxylated Wheat Gluten Proteins: A Green Solution for Production of Sustainable Superabsorbent Materials. Biomacromolecules 2020, 21, 1709–1719.

- Johansson, E.; Malik, A.H.; Hussain, A.; Rasheed, F.; Newson, W.R.; Plivelic, T.; Hedenqvist, M.S.; Gällstedt, M.; Kuk-taite, R. Wheat gluten polymer structures: The impact of genotype, environment and processing on their functionality in various applications. Cereal Chem. 2013, 90, 367–376.

- Schlichtherle-Cerny, H.; Amadò, R. Analysis of taste-active compounds in an enzymatic hydroly-sate of deamidated wheat gluten. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 1515–1522.

- Wang, J.-S.; Zhao, M.-M.; Zhao, Q.-Z.; Jiang, Y.-M. Antioxidant properties of papain hydrolysates of wheat gluten in different oxidation systems. Food Chem. 2007, 101, 1658–1663.

- Zhang, W.; Lv, T.; Li, M.; Wu, Q.; Yang, L.; Liu, H.; Sun, D.; Sun, L.; Zhuang, Z.; Wang, D. Beneficial effects of wheat gluten hydrolysate to extend lifespan and induce stress resistance in nematode Caenorhab-ditis elegans. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e74553.

- Capezza Villa, A.J. Sustainable Biobased Protein Superabsorbents from Agricultural Co-Products. Doctoral Dissertation, KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden, 2020.

- Kärenlampi, S.O.; White, P.J. Potato proteins, lipids, and minerals. In Advances in Potato Chemistry and Technology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009; pp. 99–125.

- Grubben, N.L.M.; van Heeringen, L.; Keesman, K.J. Modelling Potato Protein Content for Large-Scale Bulk Storage Facilities. Potato Res. 2019, 62, 333–344.

- Chintagunta, A.D.; Jacob, S.; Banerjee, R. Integrated bioethanol and biomanure production from potato waste. Waste Manag. 2016, 49, 320–325.

- An, V.; Evelien, D.; Katrien, B. Life Cycle Assessment Study of Starch Products for the European Starch Industry Association (AAF): Sector Study; Flemish Institute for Technological Research NV, Boeretang: 2012. Available online: http://www.starch.eu/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/2012-08-Eco-profile-of-starch-products-summary-report.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- Capezza, A.J.; Glad, D.; Özeren, H.D.; Newson, W.R.; Olsson, R.T.; Johansson, E.; Hedenqvist, M.S. Novel sus-tainable super absorbents: A one-pot method for functionalization of side-stream potato proteins. ACS Sust. Chem. Eng. 2019, 2, 17845–17854.

- Kujawska, M.; Olejnik, A.; Lewandowicz, G.; Kowalczewski, P.; Forjasz, R.; Jodynis-Liebert, J. Spray-Dried Potato Juice as a Potential Functional Food Component with Gastrointestinal Protective Effects. Nutrients 2018, 10, 259.

- Kowalczewski, P.; Różańska, M.; Makowska, A.; Jezowski, P.; Kubiak, P. Production of wheat bread with spray-dried potato juice: Influence on dough and bread characteristics. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2018, 25, 223–232.

More

Information

Subjects:

Plant Sciences

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.0K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

30 Dec 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No