Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | George Imataka | -- | 2612 | 2022-12-29 10:25:33 | | | |

| 2 | Catherine Yang | -4 word(s) | 2608 | 2022-12-29 10:29:10 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Imataka, G.; Kuwashima, S.; Yoshihara, S. Pediatric Acute Encephalopathy. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/39574 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Imataka G, Kuwashima S, Yoshihara S. Pediatric Acute Encephalopathy. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/39574. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Imataka, George, Shigeko Kuwashima, Shigemi Yoshihara. "Pediatric Acute Encephalopathy" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/39574 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Imataka, G., Kuwashima, S., & Yoshihara, S. (2022, December 29). Pediatric Acute Encephalopathy. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/39574

Imataka, George, et al. "Pediatric Acute Encephalopathy." Encyclopedia. Web. 29 December, 2022.

Copy Citation

Acute encephalopathy typically affects previously healthy children and often results in death or severe neurological sequelae. Acute encephalopathy is a group of multiple syndromes characterized by various clinical symptoms, such as loss of consciousness, motor and sensory impairments, and status convulsions.

acute encephalopathy

convulsions

pediatrics

brain hypothermia

1. Diagnosis

A coma with obvious consciousness impairment or a convulsive condition is a clinical indicator of acute encephalopathy; however, identifying acute encephalopathy in these circumstances is fairly easy. However, there are various early signs and symptoms as well as variations in these symptoms. This large range of clinical symptoms mirrors the wide range of cerebral function abnormalities as provided by the International Encephalitis Consortium, which recommends the diagnosis of encephalitis and encephalopathy of presumed infectious or autoimmune etiology. An altered mental state is a major criterion. Additional criteria (minor) to substantiate diagnosis include fever ≥38 °C (100.4 °F) within the 72 h before or after presentation; generalized or partial seizures not fully attributable to a pre-existing seizure disorder; new onset of focal neurological findings; cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) white blood count ≥5 mm3; and electroencephalographic abnormality that is consistent with encephalopathy and not caused by another factor or and not caused by another condition [1].

A clinical examination and a management plan for a child with encephalopathy should be developed concurrently. As soon as possible, a full history should be obtained. A thorough neurologic examination should be performed to localize brain damage and evaluate early prognostic indicators as well as to detect systemic symptoms such as rash, lymphadenopathy, and hepatosplenomegaly [2]. During a physical examination, clinical procedures such as mental status tests, memory tests, and coordination tests that record an altered mental state are commonly used to diagnose encephalopathy. Clinical test results are frequently used to diagnose or presumptively diagnose encephalopathy. When the altered mental state occurs associated with another primary disorder, such as chronic liver disease, kidney failure, anoxia, or a variety of other conditions, the diagnosis is typically made [3][4][5]. Glucose, ammonia, lactate, and ketone body levels in the blood as well as plasma acid–base status can all be used to help identify the subtype associated with genetic metabolic illnesses. The eventual diagnosis is based on certain laboratory findings at the start and/or during the static periods [6].

The cytokine storm subtype is distinguished by a significant increase in inflammatory tumor necrosis factor and interleukin concentrations in the serum and CSF [7]. Patients with disseminated intravascular coagulation and hemophagocytic syndrome have significant increases in ferritin, serum aminotransferase, pancreatic amylases, creatine kinase, creatinine, and uric acid nitrogen as well as ferritin, serum aminotransferase, pancreatic amylases, creatine kinase, creatinine, and uric acid nitrogen [5]. Clinical evidence, such as a biphasic pattern of seizure and varying degrees of altered states of consciousness as well as characteristic patterns of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and cerebral flow images using single-photon emission computed tomography, should be used to diagnose the excitotoxic crisis subtype [5].

EEG is a widely used technique for detecting and monitoring children with acute encephalopathy. Technological advancement has greatly simplified long-term bedside EEG monitoring. EEG has the advantage of being able to examine real-time brain function by recording electrical activity in the brain. Some children with acute encephalopathy are extremely ill and unstable in general. Even under these conditions, EEG monitoring is possible [6]. Several studies on long-term EEG monitoring among critically ill children with reduced consciousness, including those with acute encephalopathy, have recently been published. There have been numerous studies published on conventional EEG findings in children with acute encephalopathy. According to these results, EEG abnormalities are extremely common among children with acute encephalopathy. As a result, EEG is deemed to be useful in diagnosing acute encephalopathy. These EEG abnormalities include generalized/unilateral/focal slowness, low voltage, periodic lateralized epileptiform discharges, and paroxysmal discharges [8][9][10][11].

EEG has demonstrated its ability to detect nonconvulsive status epilepticus in AESD and FIRES/AERRPS (intermittent, latent seizures) [12][13]. EEG data may aid in differentiating AESD from long-term febrile seizures. Children with prolonged seizures and fever, reduced or absent spindles/fast waves as well as continuous or frequent slowing during sleep are diagnosed with AESD [14]. When combined with the clinical picture in patients with encephalopathy, EEG and brain imaging may improve diagnosis and have prognostic significance. The most common EEG finding in patients with encephalopathy is isolated persistent slowing of background activity. These patterns are linked to a variety of structural and non-structural pathologies.

The analysis of CSF is critical for determining the cause of encephalitis and distinguishing it from other types of encephalopathy. Lumbar puncture (LP) should be performed as soon as possible in suspected cases of encephalitis unless contraindicated. Clinical evaluation rather than cranial computerized tomography (CT) should be used to determine whether or not an LP is safe to perform [15][16]. Increased total protein and CSF/serum albumin quotient levels may be linked to severe edema [17]. Increased levels of cytokines and chemokines in CSF and serum may indicate an overly aggressive immune response [18]. CSF examination may reveal pleocytosis in some disorders [19], whereas pleocytosis may be uncommon in others [17].

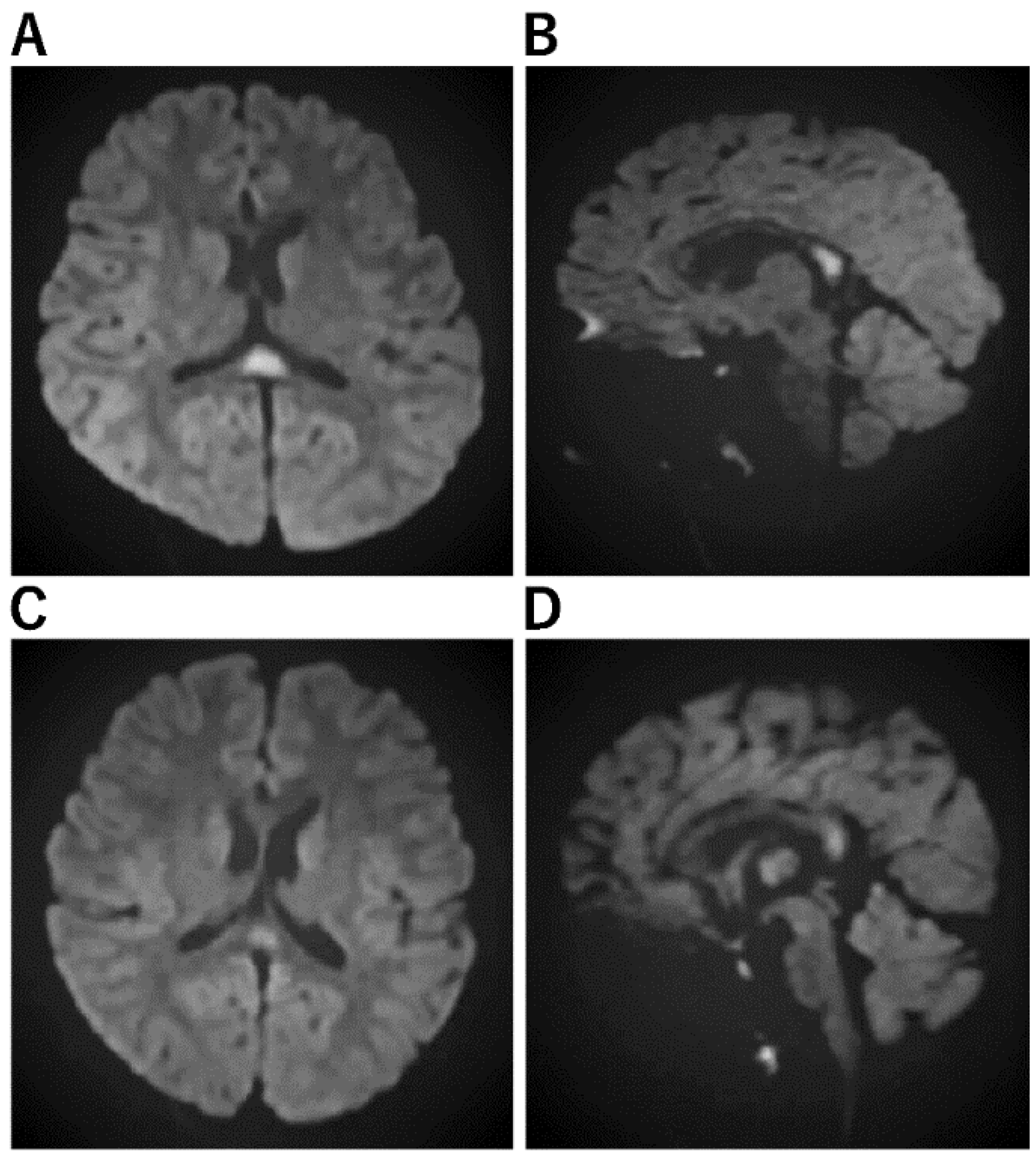

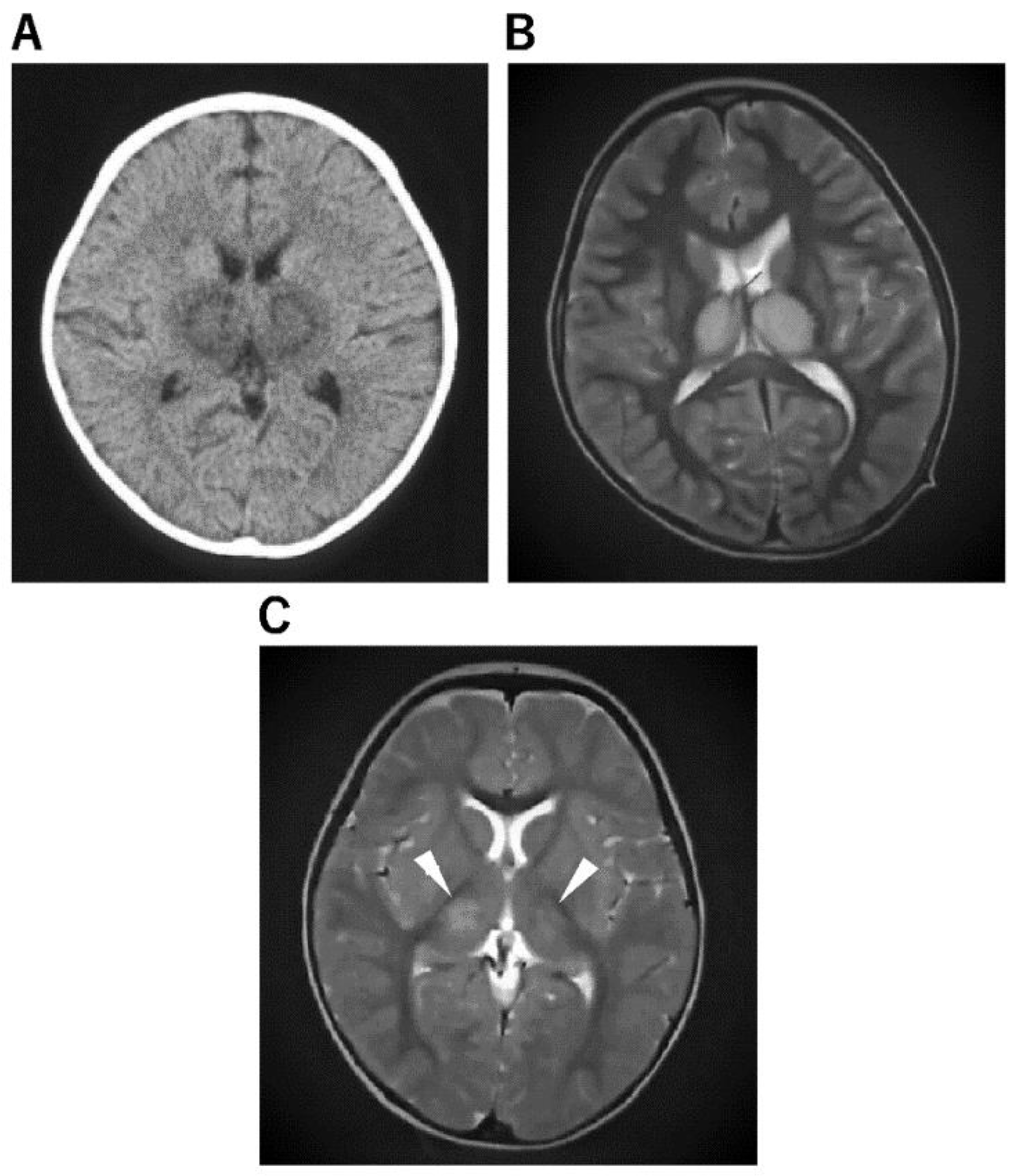

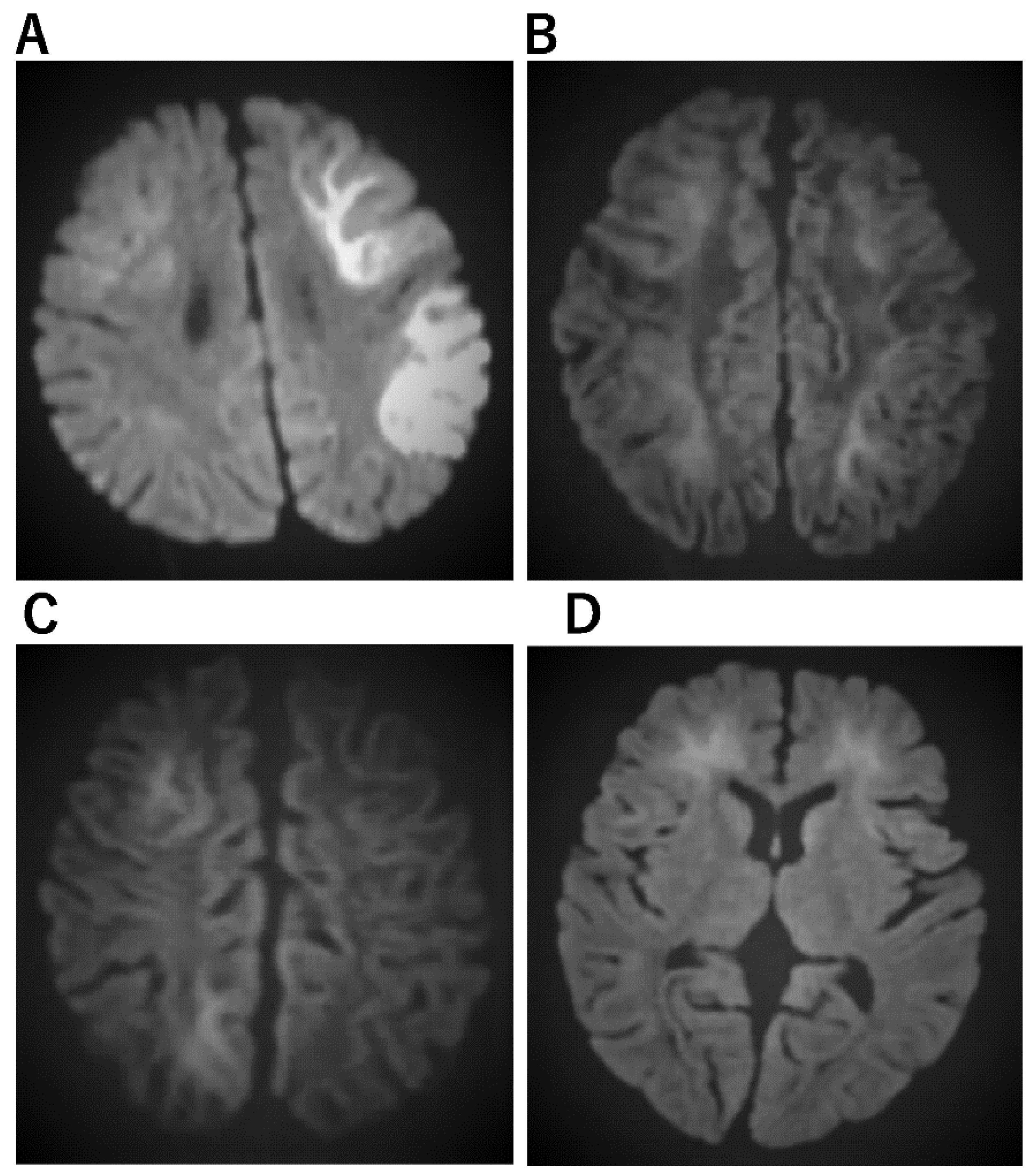

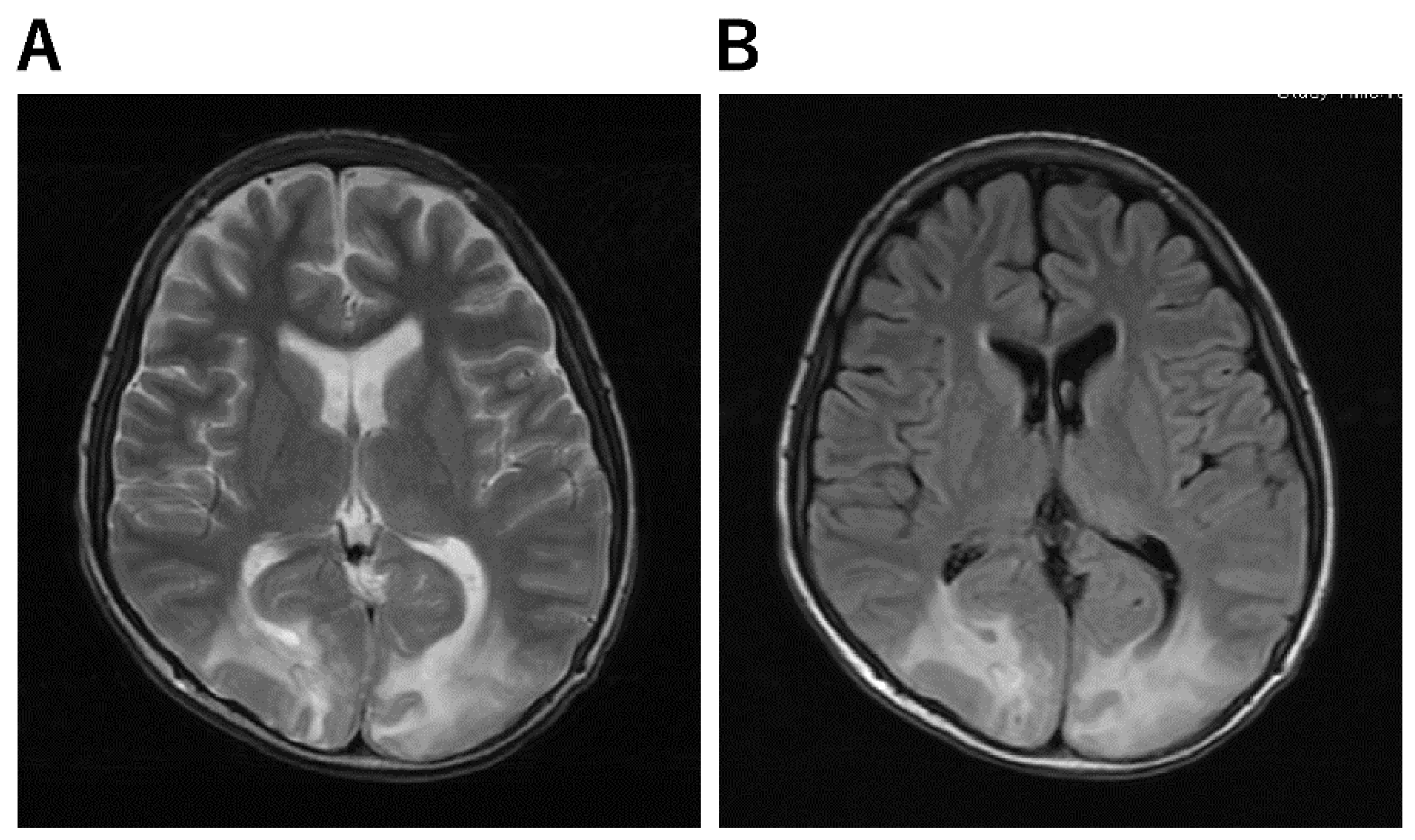

Since 2000, imaging technology such as CT, MRI, SPECT, PET, and a variety of other neuroradiological tools have been used to treat heterogeneous acute encephalopathy syndrome. Acute encephalopathy was first defined using neuroradiographic images and clinical data derived from imaging, and it has since advanced significantly. It was possible to see fine cerebral edema images in acute encephalopathy. Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4 illustrate imagining characteristics of MERS, ANE, AESD, and PRES, respectively. When acute encephalopathy is suspected, CT is usually the first test performed, because it is available in the majority of Japanese regional centers and has a quick imaging time. Acute encephalopathy is identified by cranial CT abnormalities [6][20], which include: (1) low-density zones spanning the entire brain or possibly the entire cerebral cortex, (2) no clear distinction between the cerebral cortex and the limbic system medulla, (3) both the surface of the cerebral subarachnoid space and the ventricles becoming narrower, (4) areas of low density: bilateral thalamus (ANE) and unilateral cerebral hemisphere (in some cases of AESD), (5) narrowing of the brain’s surrounding cisterns: swelling of the brainstem.

Figure 1. Imaging Characteristics of MERS. (A,B): A Horizontal/B sagittal section was performed on an 8-year-old boy who had an MRI on the third day of fever due to impaired consciousness and unable to recognize his own name. DWI showed an abnormal high signal in the cerebral corpus callosum: WBC 24800, CRP 7.84, Na 133, CL 95, ferritin 119.9, IL-6 171 EEG showed high amplitude slow waves in the occipital region. After 3 days of steroid pulse therapy, the fever resolved and consciousness improved. No sequelae. No causative organism or virus could be identified. (C,D): On the third day of vomiting and fever, he was hospitalized because he could no longer talk to his mother and could not look at her. He had diarrhea and was positive for rotavirus antigen in stool. In the bilateral frontal and occipital regions, EEG revealed persistent high amplitude slow waves. He was diagnosed with MERS on the fifth day after a diffusion-weighted MRI revealed an abnormally high signal in the corpus callosum. mPSL steroid pulse therapy was administered for three days, his level of consciousness improved, and both EEG and MRI were normalized.

Figure 2. Imaging Characteristics of ANE. (A): An 11-month-old boy was admitted to the hospital after experiencing fever and vomiting. He was given a cold medicine prescription and sent home, but the next day, after a 3 min febrile convulsion, his loss of consciousness lasted 12 h, and a second 3 min convulsion was noted, so a CT was performed. He was diagnosed with ANE after a CT scan of the brain revealed abnormalities in the bilateral thalamus. (B): A 4-year-old boy visited the hospital with a high fever, vomiting, impaired consciousness, and convulsions. The rapid influenza A antigen test was positive, and MRI indicated abnormal signals in the bilateral thalamus not only on diffusion-weighted but also on T2 images, leading to the diagnosis of ANE. The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit immediately after being diagnosed with ANE. He was given cerebral sedation with high-dose barbital therapy and cerebral hypothermia at 34.5 °C for 48 h, which was followed by TTM as temperature control therapy, IVIG high-dose therapy, and mPSL steroid pulse therapy. Mitochondrial cocktail therapy was used in combination with 2 months after onset; the patient was able to walk, and 4 months later, his speech function had recovered to the same level as before the onset. (C): A 1-year and 2-month-old girl was admitted to the hospital with fever and partial seizures. After an MRI the next day, the T2-weighted image showed abnormal signals in the bilateral thalamus and diagnosed ANE. She was treated in the intensive care unit with 72 h 34.5 °C brain hypothermia, steroid pulse therapy, IVIG, and mitochondrial cocktail therapy. The patient was given cerebral sedation with high-dose barbital therapy and she was treated with dextromethorphan, which saved her life, but she was left with severe neurological sequelae.

Figure 3. Imaging characteristics of AESD. (A) An 11-month-old boy who was admitted to the hospital with a high fever and 15 min seizure congestion of the right upper and lower extremities. The seizures stopped after the administration of midazolam. Thereafter, there was transient Todd’s palsy of the right upper and lower extremities. Brain MRI was normal. The fever resolved 3 days later and a rash appeared, which was clinically diagnosed as HHV-6 infection. The second diffusion-weighted brain MRI showed a bright tree appearance sign predominantly on the left side, diagnosing AESD. mPSL 30 mg/kg 3 days pulse therapy was administered. At the age of 6, he entered a regular elementary school, but his language skills were mildly poor. (B) A 3-year and 3-month-old girl. She has a 1 h febrile convulsion superimposed on fever. Midazolam brought the convulsions to a halt. The next day, she remained listless and was monitored with intravenous fluids; on the eighth day, she experienced a cluster of short convulsions in her limbs. Diffusion-weighted brain MRI revealed bilateral subcortical white matter predominance with bright tree appearance and an AESD diagnosis. Then, 48 h of mild cerebral hypothermia at 35.5 °C, steroid pulse therapy, and mitochondrial rescue therapy were performed. Six years after onset, she is living a normal fourth-grade elementary school life with no sequelae in terms of motor, language, or academic performance. (C) A 1-year and 7-month-old boy. After 4 days of febrile convulsive seizures, the fever subsided and a rash appeared; he was clinically diagnosed with HHV-6 infection. Multiple convulsive seizures lasting a few minutes were observed 5 days later. Slow waves were detected in the frontal and occipital regions of the EEG. Diffusion-weighted brain MRI showed an abnormally high signal in subcortical white matter and diagnosed AESD. mPSL pulse therapy and vitamin cocktail therapy were started. Body temperature was maintained at 35.5–36.0 TTM for 5 days The disease has been present for over two and a half years, and the child is now over 4 years old. There are no neurological sequelae and both language and motor functions are age-appropriate. (D) A 1-year-old boy with a fever of 39 °C and spontaneous convulsions that stopped spontaneously before reaching the hospital; 4 days later, he presents with two 3-min generalized convulsions and is rushed to the emergency room with no recovery of consciousness. He was admitted directly to the ICU, sedated with Rabonar, and given 48 h of mild cerebral hypothermia at 35 °C. Steroid pulse therapy was also administered. Thereafter, the temperature was kept at 36 °C, and the patient was transferred from the ICU to the general ward on the eighth day. On the same day, a brain MRI showed an abnormally high signal on diffusion-weighted images with bilateral frontal lobe predominance, and a diagnosis of AIEF-type AESD was made. Rehabilitation was continued until he was over 2 years old. After 1 year of onset, both his motor and language functions have recovered to the level of his age.

Figure 4. Imaging Characteristics of PRES. (A,B): A 13-year-old boy underwent skin graft surgery due to severe burns all over his body. He was on ventilatory management and sedatives for a long period of time postoperatively. As his generalized sepsis improved, his anesthetic was reduced and he was awakened; after 50 days, his consciousness improved completely; on day 51, he complained that “everything I see is white and I can’t see anything.” He then had a severe headache. His blood pressure was 150/89 mmHg and he had hypertension. Brain MRI scan showed an abnormal high signal in bilateral occipital areas on T2-weighted (A) and FLAIR (B) images, and he was diagnosed with PRES.

Acute encephalopathy should be distinguished from other conditions that cause acute loss of consciousness during infectious diseases, such as intracranial infection (e.g., viral encephalitis and bacterial meningitis), autoimmune encephalitis, cerebrovascular diseases, traumatic, metabolic, and toxic disorders, and organ failure effects. The most recent Japanese guidelines listed several differential diagnoses of acute encephalopathy [6].

2. Management

The current national pediatric acute encephalopathy guideline [6] is based on expert consensus and case series and retrospective case-control studies for specific therapies such as corticosteroids [21], immunoglobulin [22], free-radical scavenger [23], osmotic agents [24], immunosuppressant [25], plasmapheresis, and therapeutic hypothermia [26]. Even though no drugs or therapeutic practices have been systematically demonstrated to lessen the sequelae of acute encephalopathy, the use of barbiturates and steroids has increased over time. This could be due to new research highlighting the importance of early aggressive therapy in the treatment of febrile status epilepticus [27]. Only surrogate markers such as fever and inflammatory changes in the CSF as well as neuroimaging are used to rule in or rule out infections in the early stages of infection. It is important to notice clinical clues from history and examination when narrowing down the etiology and deciding on an initial treatment approach. Proper head placement, suctioning of oropharyngeal secretions, and, if necessary, the use of oropharyngeal or nasopharyngeal airways should all be used to ensure airway patency in patients with diminished consciousness [15]. Children who exhibit signs of poor ventilation and oxygenation, such as irregular respiratory efforts, insufficient chest movements, poor air entry, central cyanosis, or peripheral oxygen saturation of 92% or less should be given a bag and mask first, which is followed by endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation. For emergency intubation, rapid sequence intubation is recommended to avoid aspiration and a rapid rise in ICP. Thiopental/midazolam, lidocaine, fentanyl, and a short-acting non-depolarizing neuromuscular blocking drug are among the induction agents (e.g., vecuronium, atracurium). Hypoglycemia and hyponatremia can accompany derangements in critically ill children, potentially exacerbating the underlying disease’s encephalopathy. When glucose levels of 60 mg/dL are treated promptly with 2 mL/kg of intravenous 25% dextrose, the neurologic symptoms are frequently reversed. Meanwhile, 5 mL/kg of 3% saline is required to raise sodium levels to acceptable levels in an asymptomatic child with a plasma sodium of 125 mEq/L [6].

Antimicrobials should be given to children with infectious diseases as soon as possible rather than waiting for laboratory confirmation.

Steroid pulse therapy, particularly cytokine storm therapy, is commonly used to treat virus-associated acute encephalopathy. The prognosis may be improved by beginning steroids within 24 h of the onset of ANE. It might be useful for treating encephalopathy caused by Escherichia coli O111, which produces Shiga toxin. However, in a recent study, steroid pulse treatment within 24 h did not improve the prognosis in children with suspected acute encephalopathy in the presence of AST. However, if treatment is started earlier, the neurological consequences of this illness could be avoided [28].

The cornerstone treatment for refractory status epilepticus is intravenous general anesthetics (such as midazolam, propofol, and barbiturates) [29]. General anesthetics, in contrast, can cause cardiovascular instability, respiratory suppression, infections, metabolic abnormalities, paralytic ileus, ischemic bowel, and thromboembolic events [30]. When general anesthetic therapy fails, several pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic approaches have been documented. Ketogenic diet can be considered for the treatment of acute encephalitis with refractory, repetitive partial seizures (FIRES/AERPPS).

References

- Venkatesan, A.; Tunkel, A.R.; Bloch, K.C.; Lauring, A.S.; Sejvar, J.; Bitnun, A.; Stahl, J.-P.; Mailles, A.; Drebot, M.; Rupprecht, C.E.; et al. Case Definitions, Diagnostic Algorithms, and Priorities in Encephalitis: Consensus Statement of the International Encephalitis Consortium. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2013, 57, 1114–1128.

- Britton, P.N.; Eastwood, K.; Paterson, B.; Durrheim, D.N.; Dale, R.C.; Cheng, A.; Kenedi, C.; Brew, B.; Burrow, J.; Nagree, Y.; et al. Consensus guidelines for the investigation and management of encephalitis in adults and children in Australia and New Zealand. Intern. Med. J. 2015, 45, 563–576.

- Takahashi, A.; Kamei, E.; Sato, Y.; Shimada, S.; Tsubokawa, M.; Ohta, G.; Ohshima, Y.; Matsumine, A. Infant with right hemiplegia due to acute encephalopathy with biphasic seizures and late reduced diffusion (AESD): A case report. Medicine 2021, 100, e25468.

- Lim, J.; Kwek, S.; How, C.; Chan, W. A clinical approach to encephalopathy in children. Singap. Med. J. 2020, 61, 626–632.

- Erkkinen, M.G.; Berkowitz, A.L. A Clinical Approach to Diagnosing Encephalopathy. Am. J. Med. 2019, 132, 1142–1147.

- Mizuguchi, M.; Ichiyama, T.; Imataka, G.; Okumura, A.; Goto, T.; Sakuma, H.; Takanashi, J.I.; Murayama, K.; Yamagata, T.; Yamanouchi, H.; et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute encephalopathy in childhood. Brain Dev. 2021, 43, 2–31.

- Barbosa-Silva, M.C.; Lima, M.N.; Battaglini, D.; Robba, C.; Pelosi, P.; Rocco, P.R.M.; Maron-Gutierrez, T. Infectious disease-associated encephalopathies. Crit. Care 2021, 25, 236.

- Mohammad, S.S.; Soe, S.M.; Pillai, S.C.; Nosadini, M.; Barnes, E.H.; Gill, D.; Dale, R.C. Etiological associations and outcome predictors of acute electroencephalography in childhood encephalitis. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2016, 127, 3217–3224.

- Maegaki, Y.; Kondo, A.; Okamoto, R.; Inoue, T.; Konishi, K.; Hayashi, A.; Tsuji, Y.; Fujii, S.; Ohno, K. Clinical Characteristics of Acute Encephalopathy of Obscure Origin: A Biphasic Clinical Course Is a Common Feature. Neuropediatrics 2006, 37, 269–277.

- Okumura, A.; Suzuki, M.; Kidokoro, H.; Komatsu, M.; Shono, T.; Hayakawa, F.; Shimizu, T. The spectrum of acute encephalopathy with reduced diffusion in the unilateral hemisphere. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 2009, 13, 154–159.

- Hosoya, M.; Ushiku, H.; Arakawa, H.; Morikawa, A. Low-voltage activity in EEG during acute phase of encephalitis predicts unfavorable neurological outcome. Brain Dev. 2002, 24, 161–165.

- Okumura, A.; Komatsu, M.; Abe, S.; Kitamura, T.; Matsui, K.; Ikeno, M.; Shimizu, T. Amplitude-integrated electroencephalography in patients with acute encephalopathy with refractory, repetitive partial seizures. Brain Dev. 2011, 33, 77–82.

- Accolla, E.A.; Kaplan, P.W.; Maeder-Ingvar, M.; Jukopila, S.; Rossetti, A. Clinical correlates of frontal intermittent rhythmic delta activity (FIRDA). Clin. Neurophysiol. 2011, 122, 27–31.

- Ohno, A.; Okumura, A.; Fukasawa, T.; Nakata, T.; Suzuki, M.; Tanaka, M.; Okaia, Y.; Ito, Y.; Yamamoto, H.; Tsuji, T.; et al. Acute encephalopathy with biphasic seizures and late reduced diffusion: Predictive EEG findings. Brain Dev. 2022, 44, 221–228.

- Solomon, T.; Hart, I.J.; Beeching, N.J. Viral encephalitis: A clinician’s guide. Pract. Neurol. 2007, 7, 288–305.

- Kneen, R.; Solomon, T.; Appleton, R. The role of lumbar puncture in children with suspected central nervous system infection. BMC Pediatr. 2002, 2, 8.

- Neeb, L.; Hoekstra, J.; Endres, M.; Siegerink, B.; Siebert, E.; Liman, T.G. Spectrum of cerebral spinal fluid findings in patients with posterior reversible enceph-alopathy syndrome. J. Neurol. 2016, 263, 30–34.

- Okada, T.; Fujita, Y.; Imataka, G.; Takase, N.; Tada, H.; Sakuma, H.; Takanashi, J.-I. Increased cytokines/chemokines and hyponatremia as a possible cause of clinically mild encephalitis/encephalopathy with a reversible splenial lesion associated with acute focal bacterial nephritis. Brain Dev. 2022, 44, 30–35.

- Imataka, G.; Yoshihara, S. Immature ovarian teratoma with anti-NMDA-receptor encephalitis in a 13-year-old Japanese female patient. Med. J. Malays. 2021, 76, 436–437.

- Mizuguchi, M. Influenza encephalopathy and related neuropsychiatric syndromes. Influ. Other Respir. Viruses 2013, 7, 67–71.

- Okumura, A.; Mizuguchi, M.; Kidokoro, H.; Tanaka, M.; Abe, S.; Hosoya, M.; Aiba, H.; Maegaki, Y.; Yamamoto, H.; Tanabe, T.; et al. Outcome of acute necrotizing encephalopathy in relation to treatment with corticosteroids and gammaglobulin. Brain Dev. 2009, 31, 221–227.

- Esen, F.; Ozcan, P.E.; Tuzun, E.; Boone, M.D. Mechanisms of action of intravenous immunoglobulin in septic encephalopathy. Rev. Neurosci. 2018, 29, 417–423.

- Shima, T.; Okumura, A.; Kurahashi, H.; Numoto, S.; Abe, S.; Ikeno, M.; Shimizu, T. A nationwide survey of norovirus-associated encephalitis/encephalopathy in Japan. Brain Dev. 2019, 41, 263–270.

- Tanuma, N.; Miyata, R.; Nakajima, K.; Okumura, A.; Kubota, M.; Hamano, S.-I.; Hayashi, M. Changes in Cerebrospinal Fluid Biomarkers in Human Herpesvirus-6-Associated Acute Encephalopathy/Febrile Seizures. Mediat. Inflamm. 2014, 2014, 564091.

- Gwer, S.; Gatakaa, H.; Mwai, L.; Idro, R.; Newton, C.R. The role for osmotic agents in children with acute encephalopathies: A systematic review. BMC Pediatr. 2010, 10, 23.

- Nishiyama, M.; Tanaka, T.; Fujita, K.; Maruyama, A.; Nagase, H. Targeted temperature management of acute encephalopathy without AST elevation. Brain Dev. 2015, 37, 328–333.

- Hayakawa, I.; Okubo, Y.; Nariai, H.; Michihata, N.; Matsui, H.; Fushimi, K.; Yasunaga, H. Recent treatment patterns and variations for pediatric acute encephalopathy in Japan. Brain Dev. 2020, 42, 48–55.

- Ishida, Y.; Nishiyama, M.; Yamaguchi, H.; Tomioka, K.; Takeda, H.; Tokumoto, S.; Toyoshima, D.; Maruyama, A.; Seino, Y.; Aoki, K.; et al. Early steroid pulse therapy for children with suspected acute encephalopathy. Medicine 2021, 100, e26660.

- Neal, E.G.; Chaffe, H.M.; Schwartz, R.H.; Lawson, M.S.; Edwards, N.; Fitzsimmons, G.; Whitney, A.; Cross, J.H. A randomized controlled trial of classical and medium chain triglyceride ketogenic diets in the treatment of childhood epilepsy. Epilepsia 2008, 49, 9.

- Brophy, G.M.; Bell, R.; Claassen, J.; Alldredge, B.; Bleck, T.P.; Glauser, T.; Laroche, S.M.; Riviello, J.J.J.; Shutter, L.; Sperling, M.R.; et al. Guidelines for the evaluation and management of status epilepticus. Neurocrit. Care 2012, 7, 3–23.

More

Information

Subjects:

Neurosciences

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.2K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

29 Dec 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No