| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Clara I Rodriguez | -- | 3971 | 2022-12-27 15:51:01 | | | |

| 2 | Amina Yu | -3 word(s) | 3968 | 2022-12-29 02:18:31 | | | | |

| 3 | Amina Yu | -3 word(s) | 3965 | 2022-12-29 09:38:36 | | |

Video Upload Options

Osteogenesis imperfecta (OI), also known as “brittle bone disease”, is a rare genetic disorder that encompasses a group of conditions affecting the connective tissue. It is characterized by a decreased bone-mineral-density (BMD) alongside increased susceptibility to bone fractures, due to an abnormality in the synthesis and/or processing of the main protein of the bone extracellular matrix (ECM), the type I collagen molecule. In approximately 85% of cases, it is caused by mutations in the COL1A1 or COL1A2 genes, encoding the α1 (I) and α2 (I) chains of type I collagen, respectively. In the remainder of the cases, mutations in up to 19 different genes related to type I collagen synthesis or processing have been identified. All these mutations contribute to two types of collagen I defects; quantitative (based on the reduction of type I collagen expression) and qualitative (structural alterations of the collagen I molecule). In addition to the genetic heterogeneity, OI exhibits clinical heterogeneity, mainly governed by the mutated gene, the type of mutation, the position of the mutation along the gene and the genetic background of the patient. Hence, genetic heterogeneity is translated into clinical phenotypes that range from mild (barely affected) associated with quantitative defects, to severe forms (qualitative ones), that in some cases (in the most severe phenotypes) result in perinatal mortality.

1. Osteogenesis Imperfecta Murine Models Evaluated in Preclinical Research

1.1. Osteogenesis Imperfecta Mice (oim)

1.2. Heterozygotic G610C Mice (Amish Mice)

1.3. Brittle Mice (Brtl)

1.4. Jrt Heterozygous Mice

1.5. Heterozygous Abnormal Gait 2 (Aga2) Mice

1.6. Heterozygous Col1a1±365 OI Mouse

1.7. Crtap Mouse

1.8. IFITM5 Transgenic Mice

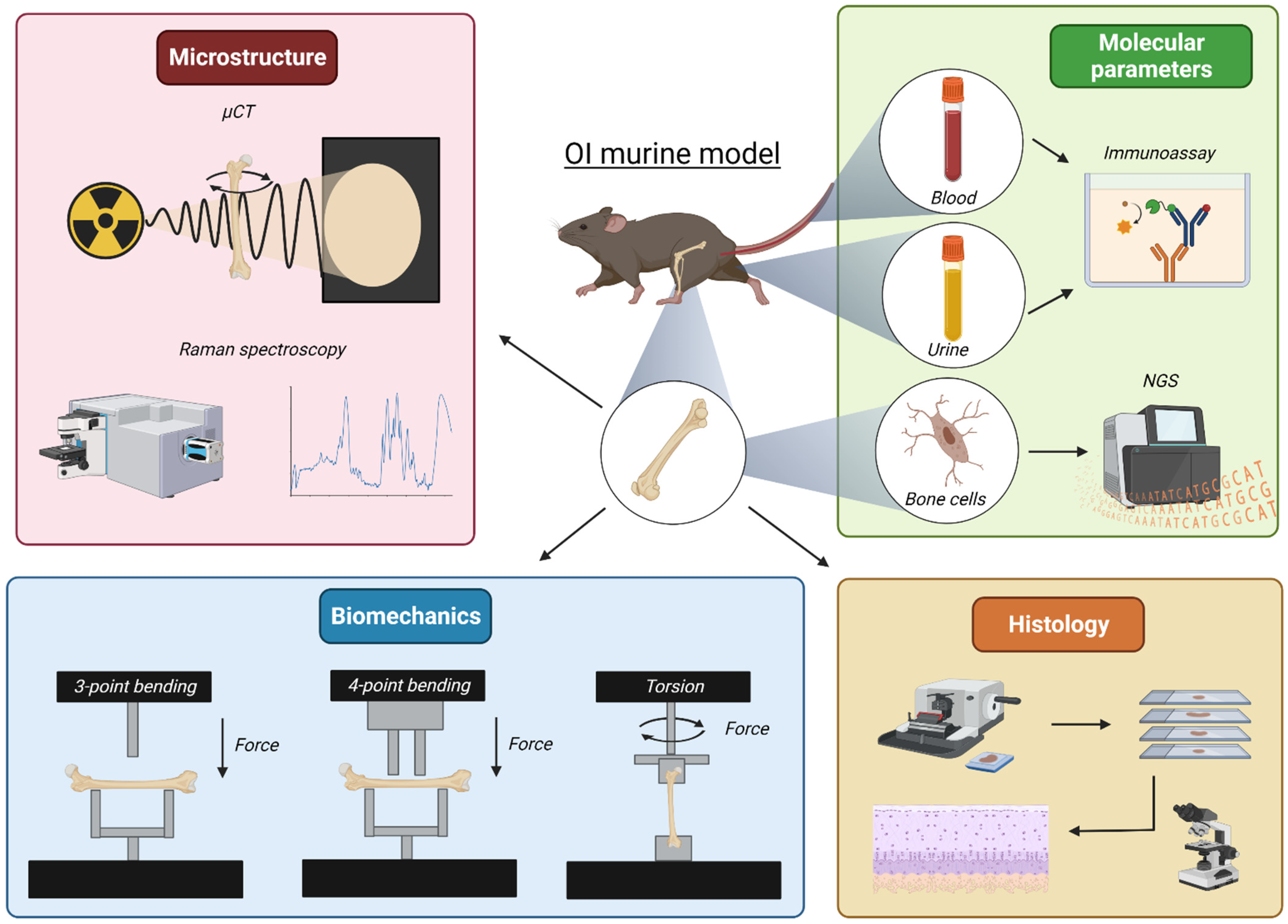

2. Revealing Parameters in Preclinical In Vivo Studies

2.1. Bone Microarchitecture

2.1.1. Microcomputed Tomography

2.1.2. Raman Spectroscopy

2.2. Bone Biomechanical Properties

2.2.1. Three- and Four-Point Bending

2.2.2. Torsional Loading to Failure

2.3. Markers in Biological Samples: Blood and Urine

2.4. Transcriptome Analysis

References

- Enderli, T.A.; Burtch, S.R.; Templet, J.N.; Carriero, A. Animal models of osteogenesis imperfecta: Applications in clinical research. Orthop. Res. Rev. 2016, 8, 41–55.

- Chipman, S.D.; Sweet, H.O.; McBride, D.J.; Davisson, M.T.; Marks, S.C.; Shuldiner, A.R.; Wenstrup, R.J.; Rowe, D.W.; Shapiro, J.R. Defective pro alpha 2(I) collagen synthesis in a recessive mutation in mice: A model of human osteogenesis imperfecta. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1993, 90, 1701–1705.

- Lee, K.J.; Rambault, L.; Bou-Gharios, G.; Clegg, P.D.; Akhtar, R.; Czanner, G.; van ’t Hof, R.; Canty-Laird, E.G. Collagen (I) homotrimer potentiates the osteogenesis imperfecta (oim) mutant allele and reduces survival in male mice. Dis. Model. Mech. 2022, 15, dmm049428.

- Pihlajaniemi, T.; Dickson, L.A.; Pope, F.M.; Korhonen, V.R.; Nicholls, A.; Prockop, D.J.; Myers, J.C. Osteogenesis imperfecta: Cloning of a pro-alpha 2(I) collagen gene with a frameshift mutation. J. Biol. Chem. 1984, 259, 12941–12944.

- Pace, J.M.; Wiese, M.; Drenguis, A.S.; Kuznetsova, N.; Leikin, S.; Schwarze, U.; Chen, D.; Mooney, S.H.; Unger, S.; Byers, P.H. Defective C-propeptides of the proalpha2(I) chain of type I procollagen impede molecular assembly and result in osteogenesis imperfecta. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 16061–16067.

- Nicholls, A.C.; Osse, G.; Schloon, H.G.; Lenard, H.G.; Deak, S.; Myers, J.C.; Prockop, D.J.; Weigel, W.R.; Fryer, P.; Pope, F.M. The clinical features of homozygous alpha 2(I) collagen deficient osteogenesis imperfecta. J. Med. Genet. 1984, 21, 257–262.

- Moffatt, P.; Boraschi-Diaz, I.; Marulanda, J.; Bardai, G.; Rauch, F. Calvaria Bone Transcriptome in Mouse Models of Osteogenesis Imperfecta. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5290.

- Zimmerman, S.M.; Dimori, M.; Heard-Lipsmeyer, M.E.; Morello, R. The Osteocyte Transcriptome Is Extensively Dysregulated in Mouse Models of Osteogenesis Imperfecta. JBMR Plus 2019, 3, e10171.

- Rodriguez-Florez, N.; Garcia-Tunon, E.; Mukadam, Q.; Saiz, E.; Oldknow, K.J.; Farquharson, C.; Millán, J.L.; Boyde, A.; Shefelbine, S.J. An investigation of the mineral in ductile and brittle cortical mouse bone. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2015, 30, 786–795.

- Maghsoudi-Ganjeh, M.; Samuel, J.; Ahsan, A.S.; Wang, X.; Zeng, X. Intrafibrillar mineralization deficiency and osteogenesis imperfecta mouse bone fragility. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2021, 117, 104377.

- Daley, E.; Streeten, E.A.; Sorkin, J.D.; Kuznetsova, N.; Shapses, S.A.; Carleton, S.M.; Shuldiner, A.R.; Marini, J.C.; Phillips, C.L.; Goldstein, S.A.; et al. Variable bone fragility associated with an Amish COL1A2 variant and a knock-in mouse model. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2010, 25, 247–261.

- Kohler, R.; Tastad, C.A.; Creecy, A.; Wallace, J.M. Morphological and mechanical characterization of bone phenotypes in the Amish G610C murine model of osteogenesis imperfecta. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0255315.

- Mirigian, L.S.; Makareeva, E.; Mertz, E.L.; Omari, S.; Roberts-Pilgrim, A.M.; Oestreich, A.K.; Phillips, C.L.; Leikin, S. Osteoblast Malfunction Caused by Cell Stress Response to Procollagen Misfolding in α2(I)-G610C Mouse Model of Osteogenesis Imperfecta. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2016, 31, 1608–1616.

- Gorrell, L.; Makareeva, E.; Omari, S.; Otsuru, S.; Leikin, S. ER, Mitochondria, and ISR Regulation by mt-HSP70 and ATF5 upon Procollagen Misfolding in Osteoblasts. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, e2201273.

- Besio, R.; Maruelli, S.; Battaglia, S.; Leoni, L.; Villani, S.; Layrolle, P.; Rossi, A.; Trichet, V.; Forlino, A. Early Fracture Healing is Delayed in the Col1a2. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2018, 103, 653–662.

- Forlino, A.; Porter, F.D.; Lee, E.J.; Westphal, H.; Marini, J.C. Use of the Cre/lox recombination system to develop a non-lethal knock-in murine model for osteogenesis imperfecta with an alpha1(I) G349C substitution. Variability in phenotype in BrtlIV mice. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 37923–37931.

- Forlino, A.; Tani, C.; Rossi, A.; Lupi, A.; Campari, E.; Gualeni, B.; Bianchi, L.; Armini, A.; Cetta, G.; Bini, L.; et al. Differential expression of both extracellular and intracellular proteins is involved in the lethal or nonlethal phenotypic variation of BrtlIV, a murine model for osteogenesis imperfecta. Proteomics 2007, 7, 1877–1891.

- Bianchi, L.; Gagliardi, A.; Gioia, R.; Besio, R.; Tani, C.; Landi, C.; Cipriano, M.; Gimigliano, A.; Rossi, A.; Marini, J.C.; et al. Differential response to intracellular stress in the skin from osteogenesis imperfecta Brtl mice with lethal and non lethal phenotype: A proteomic approach. J. Proteom. 2012, 75, 4717–4733.

- Uveges, T.E.; Collin-Osdoby, P.; Cabral, W.A.; Ledgard, F.; Goldberg, L.; Bergwitz, C.; Forlino, A.; Osdoby, P.; Gronowicz, G.A.; Marini, J.C. Cellular mechanism of decreased bone in Brtl mouse model of OI: Imbalance of decreased osteoblast function and increased osteoclasts and their precursors. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2008, 23, 1983–1994.

- Wallace, J.M.; Orr, B.G.; Marini, J.C.; Holl, M.M. Nanoscale morphology of Type I collagen is altered in the Brtl mouse model of Osteogenesis Imperfecta. J. Struct. Biol. 2011, 173, 146–152.

- Blouin, S.; Fratzl-Zelman, N.; Roschger, A.; Cabral, W.A.; Klaushofer, K.; Marini, J.C.; Fratzl, P.; Roschger, P. Cortical bone properties in the Brtl/+ mouse model of Osteogenesis imperfecta as evidenced by acoustic transmission microscopy. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2019, 90, 125–132.

- Kozloff, K.M.; Carden, A.; Bergwitz, C.; Forlino, A.; Uveges, T.E.; Morris, M.D.; Marini, J.C.; Goldstein, S.A. Brittle IV mouse model for osteogenesis imperfecta IV demonstrates postpubertal adaptations to improve whole bone strength. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2004, 19, 614–622.

- Forlino, A.; Kuznetsova, N.V.; Marini, J.C.; Leikin, S. Selective retention and degradation of molecules with a single mutant alpha1(I) chain in the Brtl IV mouse model of OI. Matrix Biol. 2007, 26, 604–614.

- Chen, F.; Guo, R.; Itoh, S.; Moreno, L.; Rosenthal, E.; Zappitelli, T.; Zirngibl, R.A.; Flenniken, A.; Cole, W.; Grynpas, M.; et al. First mouse model for combined osteogenesis imperfecta and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2014, 29, 1412–1423.

- Eimar, H.; Tamimi, F.; Retrouvey, J.M.; Rauch, F.; Aubin, J.E.; McKee, M.D. Craniofacial and Dental Defects in the Col1a1Jrt/+ Mouse Model of Osteogenesis Imperfecta. J. Dent. Res. 2016, 95, 761–768.

- Lisse, T.S.; Thiele, F.; Fuchs, H.; Hans, W.; Przemeck, G.K.; Abe, K.; Rathkolb, B.; Quintanilla-Martinez, L.; Hoelzlwimmer, G.; Helfrich, M.; et al. ER stress-mediated apoptosis in a new mouse model of osteogenesis imperfecta. PLoS Genet. 2008, 4, e7.

- Thiele, F.; Cohrs, C.M.; Flor, A.; Lisse, T.S.; Przemeck, G.K.; Horsch, M.; Schrewe, A.; Gailus-Durner, V.; Ivandic, B.; Katus, H.A.; et al. Cardiopulmonary dysfunction in the Osteogenesis imperfecta mouse model Aga2 and human patients are caused by bone-independent mechanisms. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012, 21, 3535–3545.

- Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, S.; Kuang, M.; Jing, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, G. A novel transgenic murine model with persistently brittle bones simulating osteogenesis imperfecta type I. Bone 2019, 127, 646–655.

- Xiang, L.; Yu, H.; Zhang, X.; Wang, B.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Ye, R.; Gong, P.; Wu, Y. The versatile hippo pathway in oral-maxillofacial development and bone remodeling. Dev. Biol. 2018, 440, 53–63.

- Marini, J.C.; Cabral, W.A.; Barnes, A.M.; Chang, W. Components of the collagen prolyl 3-hydroxylation complex are crucial for normal bone development. Cell Cycle 2007, 6, 1675–1681.

- Morello, R.; Bertin, T.K.; Chen, Y.; Hicks, J.; Tonachini, L.; Monticone, M.; Castagnola, P.; Rauch, F.; Glorieux, F.H.; Vranka, J.; et al. CRTAP is required for prolyl 3- hydroxylation and mutations cause recessive osteogenesis imperfecta. Cell 2006, 127, 291–304.

- Fratzl-Zelman, N.; Morello, R.; Lee, B.; Rauch, F.; Glorieux, F.H.; Misof, B.M.; Klaushofer, K.; Roschger, P. CRTAP deficiency leads to abnormally high bone matrix mineralization in a murine model and in children with osteogenesis imperfecta type VII. Bone 2010, 46, 820–826.

- Lietman, C.D.; Marom, R.; Munivez, E.; Bertin, T.K.; Jiang, M.M.; Chen, Y.; Dawson, B.; Weis, M.A.; Eyre, D.; Lee, B. A transgenic mouse model of OI type V supports a neomorphic mechanism of the IFITM5 mutation. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2015, 30, 489–498.

- Rauch, F.; Geng, Y.; Lamplugh, L.; Hekmatnejad, B.; Gaumond, M.H.; Penney, J.; Yamanaka, Y.; Moffatt, P. Crispr-Cas9 engineered osteogenesis imperfecta type V leads to severe skeletal deformities and perinatal lethality in mice. Bone 2018, 107, 131–142.

- Tabeta, K.; Du, X.; Arimatsu, K.; Yokoji, M.; Takahashi, N.; Amizuka, N.; Hasegawa, T.; Crozat, K.; Maekawa, T.; Miyauchi, S.; et al. An ENU-induced splice site mutation of mouse Col1a1 causing recessive osteogenesis imperfecta and revealing a novel splicing rescue. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 11717.

- Kasamatsu, A.; Uzawa, K.; Hayashi, F.; Kita, A.; Okubo, Y.; Saito, T.; Kimura, Y.; Miyamoto, I.; Oka, N.; Shiiba, M.; et al. Deficiency of lysyl hydroxylase 2 in mice causes systemic endoplasmic reticulum stress leading to early embryonic lethality. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019, 512, 486–491.

- Saito, T.; Terajima, M.; Taga, Y.; Hayashi, F.; Oshima, S.; Kasamatsu, A.; Okubo, Y.; Ito, C.; Toshimori, K.; Sunohara, M.; et al. Decrease of lysyl hydroxylase 2 activity causes abnormal collagen molecular phenotypes, defective mineralization and compromised mechanical properties of bone. Bone 2022, 154, 116242.

- Barnes, A.M.; Cabral, W.A.; Weis, M.; Makareeva, E.; Mertz, E.L.; Leikin, S.; Eyre, D.; Trujillo, C.; Marini, J.C. Absence of FKBP10 in recessive type XI osteogenesis imperfecta leads to diminished collagen cross-linking and reduced collagen deposition in extracellular matrix. Hum. Mutat. 2012, 33, 1589–1598.

- Joeng, K.S.; Lee, Y.C.; Jiang, M.M.; Bertin, T.K.; Chen, Y.; Abraham, A.M.; Ding, H.; Bi, X.; Ambrose, C.G.; Lee, B.H. The swaying mouse as a model of osteogenesis imperfecta caused by WNT1 mutations. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014, 23, 4035–4042.

- Fahiminiya, S.; Majewski, J.; Mort, J.; Moffatt, P.; Glorieux, F.H.; Rauch, F. Mutations in WNT1 are a cause of osteogenesis imperfecta. J. Med. Genet. 2013, 50, 345–348.

- Vollersen, N.; Zhao, W.; Rolvien, T.; Lange, F.; Schmidt, F.N.; Sonntag, S.; Shmerling, D.; von Kroge, S.; Stockhausen, K.E.; Sharaf, A.; et al. The WNT1G177C mutation specifically affects skeletal integrity in a mouse model of osteogenesis imperfecta type XV. Bone Res. 2021, 9, 48.

- Hedjazi, G.; Guterman-Ram, G.; Blouin, S.; Schemenz, V.; Wagermaier, W.; Fratzl, P.; Hartmann, M.A.; Zwerina, J.; Fratzl-Zelman, N.; Marini, J.C. Alterations of bone material properties in growing Ifitm5/BRIL p.S42 knock-in mice, a new model for atypical type VI osteogenesis imperfecta. Bone 2022, 162, 116451.

- Gewartowska, O.; Aranaz-Novaliches, G.; Krawczyk, P.S.; Mroczek, S.; Kusio-Kobiałka, M.; Tarkowski, B.; Spoutil, F.; Benada, O.; Kofroňová, O.; Szwedziak, P.; et al. Cytoplasmic polyadenylation by TENT5A is required for proper bone formation. Cell Rep. 2021, 35, 109015.

- Malhan, D.; Muelke, M.; Rosch, S.; Schaefer, A.B.; Merboth, F.; Weisweiler, D.; Heiss, C.; Arganda-Carreras, I.; El Khassawna, T. An Optimized Approach to Perform Bone Histomorphometry. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 666.

- van’t Hof, R.J.; Rose, L.; Bassonga, E.; Daroszewska, A. Open source software for semi-automated histomorphometry of bone resorption and formation parameters. Bone 2017, 99, 69–79.

- Xu, H.; Lenhart, S.A.; Chu, E.Y.; Chavez, M.B.; Wimer, H.F.; Dimori, M.; Somerman, M.J.; Morello, R.; Foster, B.L.; Hatch, N.E. Dental and craniofacial defects in the Crtap. Dev. Dyn. 2020, 249, 884–897.

- Masci, M.; Wang, M.; Imbert, L.; Barnes, A.M.; Spevak, L.; Lukashova, L.; Huang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Marini, J.C.; Jacobsen, C.M.; et al. Bone mineral properties in growing Col1a2(+/G610C) mice, an animal model of osteogenesis imperfecta. Bone 2016, 87, 120–129.

- Stephens, M.; López-Linares, K.; Aldazabal, J.; Macias, I.; Ortuzar, N.; Bengoetxea, H.; Bulnes, S.; Alcorta-Sevillano, N.; Infante, A.; Lafuente, J.V.; et al. Murine femur micro-computed tomography and biomechanical datasets for an ovariectomy-induced osteoporosis model. Sci. Data 2021, 8, 240.

- Kohler, R.; Tastad, C.A.; Stacy, A.J.; Swallow, E.A.; Metzger, C.E.; Allen, M.R.; Wallace, J.M. The Effect of Single Versus Group μCT on the Detection of Trabecular and Cortical Disease Phenotypes in Mouse Bones. JBMR Plus 2021, 5, e10473.

- Bouxsein, M.L.; Boyd, S.K.; Christiansen, B.A.; Guldberg, R.E.; Jepsen, K.J.; Müller, R. Guidelines for assessment of bone microstructure in rodents using micro-computed tomography. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2010, 25, 1468–1486.

- Mandair, G.S.; Morris, M.D. Contributions of Raman spectroscopy to the understanding of bone strength. Bonekey Rep. 2015, 4, 620.

- Turner, C.H.; Wang, T.; Burr, D.B. Shear strength and fatigue properties of human cortical bone determined from pure shear tests. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2001, 69, 373–378.

- Macías, I.; Alcorta-Sevillano, N.; Rodríguez, C.I.; Infante, A. Osteoporosis and the Potential of Cell-Based Therapeutic Strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1653.

- Boraschi-Diaz, I.; Tauer, J.T.; El-Rifai, O.; Guillemette, D.; Lefebvre, G.; Rauch, F.; Ferron, M.; Komarova, S.V. Metabolic phenotype in the mouse model of osteogenesis imperfecta. J. Endocrinol. 2017, 234, 279–289.

- Wang, N.; Wang, L.; Wang, Z.; Cheng, L.; Wang, J. Solanum muricatum Ameliorates the Symptoms of Osteogenesis Imperfecta In Vivo. J. Food Sci. 2019, 84, 1646–1650.