Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Junjie Luo | -- | 2225 | 2022-12-26 09:42:57 | | | |

| 2 | Camila Xu | Meta information modification | 2225 | 2022-12-26 09:59:30 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Guo, X.; Luo, J.; Qi, J.; Zhao, X.; An, P.; Luo, Y.; Wang, G. Anti-Aging Mechanism of Polysaccharides. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/39302 (accessed on 02 March 2026).

Guo X, Luo J, Qi J, Zhao X, An P, Luo Y, et al. Anti-Aging Mechanism of Polysaccharides. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/39302. Accessed March 02, 2026.

Guo, Xinlu, Junjie Luo, Jingyi Qi, Xiya Zhao, Peng An, Yongting Luo, Guisheng Wang. "Anti-Aging Mechanism of Polysaccharides" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/39302 (accessed March 02, 2026).

Guo, X., Luo, J., Qi, J., Zhao, X., An, P., Luo, Y., & Wang, G. (2022, December 26). Anti-Aging Mechanism of Polysaccharides. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/39302

Guo, Xinlu, et al. "Anti-Aging Mechanism of Polysaccharides." Encyclopedia. Web. 26 December, 2022.

Copy Citation

Polysaccharides are natural and efficient biological macromolecules that act as antioxidants, anti-inflammatories, and immune regulators.

polysaccharide

anti-aging

mechanism

Caenorhabditis elegans

1. Introduction

Aging is a complex natural phenomenon, which is manifested as structural and functional degeneration. It is the inevitable result of the synthesis of a number of processes, influenced by many physiological and psychological factors such as heredity, immunity, and environment [1]. In recent years, with economic and medical advances, the world’s life expectancy reached 71 in 2021 [2]. However, the elderly proportion of the population continues to grow. Worldwide, the proportion of people over 60 years old in the total population has increased from 9.9% in 2000 to 13.7% in 2021, with Eastern and Southeast Asia reaching 17.4%, and Europe and North America reaching 25.1% [2]. It is estimated that by 2050 there will be more than 1.5 billion people over the age of 65 [2]. Aging is usually accompanied by cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, diabetes, and other chronic diseases, and it is a great burden to the economy, health care, and society [3]. According to published data, issues surrounding the aging population are becoming increasingly more serious and will continue to worsen unless action is taken [2]. To increase healthy lifespan, one strategy is to create anti-aging medications.

Aging is accompanied by a variety of physiological processes, such as a decline in immunity, a slowing of basal metabolism, and a reduction in activity of antioxidant-related enzymes [4]. Therefore, potential anti-aging drugs can be screened from substances that have inhibitory effects on these processes. According to the different modes of action, many anti-aging theories have been proposed, including programmed theories and damage theories [5]. Programmed theories involve deliberate deterioration with age, and are likely the most relevant to aging genes as well as the endocrine system. Some scientists believe that aging is not programmed, but rather involves the accumulation of damage such as oxidative damage, mitochondrial DNA damage, and genome damage. These two theories have been thoroughly explored in previous publications [5]. Current anti-aging drugs, such as rapamycin and metformin, have demonstrated not only strong anti-aging effects in a variety of model organisms through different ways such as mTOR and AMPK, but also demonstrated promising results in preliminary clinical trials [6][7]. Zhang et al. reviewed studies on the retardation of aging by rapamycin in a variety of animal models and organ systems [8]. Rapamycin plays an anti-aging role mainly by inhibiting mTOR, which is important for mitochondrial function, metabolism, and maintenance of stem cells. According to the literature, metformin delays aging through various mechanisms, such as regulating the synthesis and degradation of age-related proteins, maintaining telomere length, and reducing DNA damage [9]. However, due to the lack of large-scale and long-term clinical trials, the above drugs still have some deficits related to safety and long-term use. For example, rapamycin has been demonstrated to extend the lifespan of mice, but it did not improve age-related characteristics; furthermore, rapamycin may cause thrombocytopenia, nephrotoxicity, and other side effects [10]. Long-term use of metformin may lead to vitamin B12 deficiency, lactic acid accumulation, and even lactic acid poisoning [11]. Taken together, the current research on anti-aging drugs is still in a relatively preliminary stage. It is also necessary to develop naturally effective anti-aging drugs with fewer side effects, thus allowing for long term use.

At present, a number of studies have demonstrated that polysaccharides extracted from natural resources have a wide range of pharmacological effects, such as anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidative, and immune modulatory effects [12]. Moreover, polysaccharides may have unique advantages in terms of side effects and long-term use due to their low cytotoxicity [12], and are expected to contribute to the development of novel anti-aging drugs or supplements [12]. Notably, some polysaccharides have been utilized in clinical practice. For example, heparin is used as an anticoagulant drug [13]. Poria cocos polysaccharide oral liquid has been approved for the treatment of many diseases, such as cancer and hepatitis [14]. In terms of anti-aging, although there is no polysaccharide drug that can be applied in clinical practice, many polysaccharides have demonstrated good effects in various animal models such as Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans), Drosophila melanogaster (D. melanogaster), and mice. For instance, angelica sinensis polysaccharide (ASP) and astragalus polysaccharide (APS) have been demonstrated to significantly prolong the life of C. elegans and D. melanogaster, and also have protective effects on the liver, kidney, brain, and other important organs in mice, thus demonstrating great potential for anti-aging therapy [15][16][17][18][19][20].

2. Anti-Aging Mechanism of Polysaccharides

Typical features of aging include a decline in basal metabolism accompanied by the decreased immune function and antioxidant capacity. The studies mentioned above suggest that polysaccharides may act to delay aging by regulating metabolism and immunity. Here, researchers introduce four widely accepted mechanisms to provide references for subsequent research on the anti-aging mechanisms of polysaccharides.

2.1. Oxidative Damage

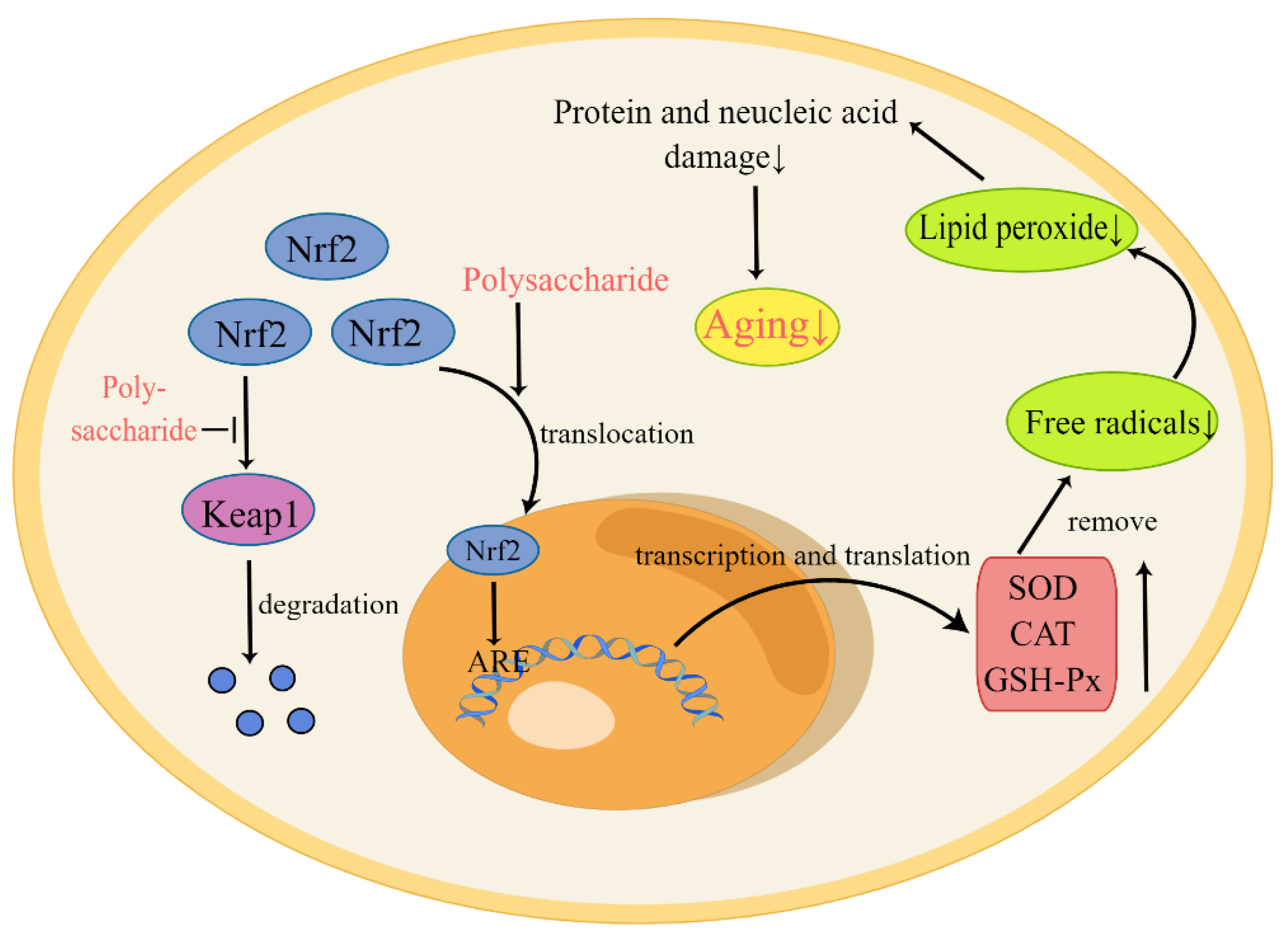

Living organisms produce free radicals during normal physiological activities, especially from the mitochondrial electron transport chain. At the same time, there are also free radical scavenging systems in the body, such as SOD, CAT, and GSH-Px [21]. However, with increased age, the balance between the two is difficult to maintain, resulting in an excess of free radicals [22]. Unsaturated fatty acids in biofilm are easily converted to lipid peroxides by free radicals. These products cause damage to proteins, nucleic acids, and other substances, which accelerates aging [23]. Additionally, since mitochondria provide energy for cells and regulate the cell cycle, excess free radicals can cause serious damage to mitochondria and accelerate the process of aging [24]. As shown in Figure 1, polysaccharides act to up-regulate the expression of antioxidant-related enzyme genes through the nuclear factor-E2-related factor 2-antioxidant response element (Nrf2-ARE) pathway, so as to remove excess free radicals and achieve the purpose of anti-aging. Nrf2 is normally bound to Keap1 and is then rapidly degraded, resulting in a low level in cells. Under the influence of polysaccharides, Nrf2 enters the nucleus and interacts with the ARE to increase the expression of antioxidant genes [23]. For example, Yang et al. isolated polysaccharides from fruit wine and identified their scavenging effects on free radicals and anti-aging effects in vivo [25]. Zhu et al. found that CCP significantly prolonged the lifespan of Drosophila by increasing the activity of SOD, CAT, and GSH-Px [26]. Finally, Li et al. demonstrated that APS acts to protect mitochondria, likely by scavenging ROS and increasing the activities of antioxidant enzymes [20]. These results demonstrate that polysaccharides not only act to improve the activity of antioxidant enzymes, but also inhibit cell apoptosis and the formation of lipid peroxides.

Figure 1. Polysaccharides delay aging by increasing the expression of antioxidant enzymes. In the figure, “↑” indicates elevated substance levels and “↓” indicates the decrease of substance levels. Under normal circumstances, Nrf2 exists in the cytoplasm and is degraded after binding to Keap1, thus maintaining a low level of Nrf2 in the cytoplasm. In the presence of polysaccharides, the binding of Nrf2 to Keap1 is inhibited, and the translocation of Nrf2 is promoted, such that it enters the nucleus and interacts with AREs. The activation of AREs promotes transcription and translation of antioxidant-related genes. These antioxidant enzymes, such as SOD, CAT, and GSH-Px, act to eliminate free radicals and delay aging.

2.2. Age-Related Genes and Pathways

Specific genes can affect the lifespan of an organism. At present, studies have identified parts of genes (e.g., p53 and p21) and pathways (e.g., IIS pathways and Wnt/β-catenin pathways) that are associated with aging and longevity, as discussed in the second section of this research [27]. Mutations or changes in the expression of these genes can significantly impact lifespan. Under normal circumstances, the p53 protein as a tumor suppressor is swiftly ubiquitinated by MDM2 and subsequently targeted for degradation by the ubiquitin-proteasome system. In conditions of DNA damage, p53 is activated by posttranslational modifications, which inhibit the interaction of p53 with MDM2 and lead to the accumulation of p53 [28]. However, p53 not only triggers apoptosis, but also induces cell cycle arrest. Therefore, the expression of the p53 gene is closely related to cell aging and DNA damage [28]. Another protein, p21, is involved in many important cellular processes, including apoptosis and DNA replication [29]. It can be used as a cell cycle regulatory protein to inhibit the activities of various cell cycle-dependent kinases, thus promoting cell cycle arrest [29]. Additionally, these two proteins are important factors in the p19Arf-Mdm2-p53-p21CIP1/Waf pathway, as discussed in Section 2.2. It has been reported that polysaccharides can affect the cell cycle by regulating the expression of these genes. For example, Yulangsan polysaccharide may enhance antioxidant activity and immune function by regulating expression of the age-related genes p53 and p21 [27].

Besides these genes, IIS is a well-studied pathway that is highly conserved in various organisms such as C. elegans, Drosophila, and mice [30]. This pathway is related to growth, development, reproduction, and aging. Under normal circumstances, IIS is active and is mainly involved in the phosphorylation of DAF-2, AGE-1, and other kinases, ultimately affecting the activity of DAF-16 transcription factors [30]. After phosphorylation, DAF-16 interacts with the 14-3-3 protein and is anchored in the cytoplasm. Inhibition of the IIS pathway by external intervention reduces the phosphorylation of DAF-16, facilitating translocation to the nucleus [31]. Furthermore, protein phosphatase 4 complex promotes the recruitment of RNA polymerase to assist the DAF-16 gene in activating the transcription of stress resistance and longevity-promoting genes, ultimately prolonging life [31]. At present, several studies have demonstrated that many kinds of polysaccharides act to prolong the lifespan in C. elegans and Drosophila models [16][32][33].

The Wnt/β-catenin pathway is one of the most important pathways related to developmental processes, and excessive activation of Wnt/β-catenin pathway may lead to varying degrees of stem cell senescence [34]. This pathway will only be activated when the Wnt protein binds to the Frizzled receptor and co-receptor LPR-5/6. Once this tri-molecular complex is formed, Dishevelled will be recruited. DVL is then phosphorylated, resulting in the inhibition of GSK-3β and accumulation of free β-catenin. The free β-catenin then translocates to the nucleus and activates genes that influence cellular processes [35][36].

2.3. Immune Modulation

The immune function of the body declines with increased age, and this mainly manifests as an infective response to infectious disease and a decreased response to vaccines [37]. Polysaccharides have been demonstrated to improve immune function by regulating inflammatory factors as well as affecting immune cells and immune organs, so as to achieve the purpose of anti-aging [27][38].

At the molecular level, various inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, such as interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and tumor necrosis factors (TNFs), show increased gene and protein expression in senescent cells compared to non-senescent cells [39]. In addition, senescent cells show excessive activation of a variety of inflammatory mediators. This overactivation of inflammatory cytokines associated with aging may be realized through the P38 and NF-ĸB pathways [39]. Mo et al. investigated whether ASP could protect against the D-Gal-induced aging in mice by attenuating inflammatory responses [18]. The results indicated that ASP could indeed inhibit the expression of inflammatory factors related to the NF-ĸB pathway, such as iNOs and COX-2, and the infiltration of the hepatic leucocytes in aged mice. This example demonstrates that polysaccharides can delay aging by attenuating inflammation. Notably, the accumulation of advanced glycosylation end products (AGEs) is an aging indicator [40]. Glycosylation begins with the carbonyl group of a carbohydrate and the amino group of a protein, which reacts to form a Schiff base. Schiff bases, however, are unstable and undergo a series of reactions, such as rearrangements, which eventually turn into AGEs. Then, AGEs trigger ROS overload and stimulate proinflammatory cytokine synthesis and release [40][41]. Therefore, the levels of AGEs and inflammatory cytokines that affect T-cell immune responses serve as important indicators of aging [42].

At the cellular level, senescent cells with complex senescence-related secretory phenotypes (SASPs) are beneficial to tissue repair and slow down the development of cancer in the short term. However, these cells may aggravate a variety of diseases in the long term [43]. T cells, macrophages, NK cells, and other immune cells may be recruited by SASP factors to eliminate senescent cells and maintain homeostasis [43]. Polysaccharides bind to specific receptors on the surface of immune cells; for instance, ganoderma lucidum polysaccharides bind to dectin-1, mannose receptor, and Toll-like receptor 4 to activate the immune response [44]. However, the mechanism of the interaction between various polysaccharides and different immune cells requires further study.

At the organ level, aging is accompanied by the degeneration of immune organs, such as the thymus and spleen. Therefore, changes in immune organs can characterize aging to a certain extent. According to the histopathological analysis of mouse liver tissue, Xia et al. found that mice without ASP had serious liver injury along with degenerative changes in hepatocytes, decreased hepatic glycogen, and accumulated AGEs [45]. In contrast, mice treated with ASP had more glycogen as well as less liver damage and AGEs.

2.4. Telomere Attrition

Telomeres maintain the integrity and stability of chromosome structure and telomerase endows cells with the ability of self-renewal [46]. However, as cells continue to divide, telomerase activity is weakened and telomeres are gradually shortened or are completely lost, eventually leading to cell aging [47]. It has been demonstrated that polysaccharides improve telomerase activity and prevent telomere loss, such that cells can divide normally and aging is delayed. For example, ASP increases telomere length and improves telomerase activity to delay senescence of HSCs induced by X-ray [17]. The anti-aging effect of polysaccharides isolated from the roots of Polygala tenuifolia is partly mediated by the down-regulation of Bmi-1 expression and the activity of telomerase in cells [48]. Fucoidan induces apoptosis and inhibits telomerase activity, which may be mediated by the ROS-dependent inactivation of the PI3K/Akt pathway [49].

References

- Dziechciaz, M.; Filip, R. Biological psychological and social determinants of old age: Bio-psycho-social aspects of human aging. Ann. Agr. Env. Med. 2014, 21, 835–838.

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World Population Prospects 2022. Online Edition ed. 2022. Available online: https://population.un.org/wpp/ (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- Lopez-Otin, C.; Blasco, M.A.; Partridge, L.; Serrano, M.; Kroemer, G. The hallmarks of aging. Cell 2013, 153, 1194–1217.

- Davalli, P.; Mitic, T.; Caporali, A.; Lauriola, A.; D’Arca, D. ROS, Cell Senescence, and Novel Molecular Mechanisms in Aging and Age-Related Diseases. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 3565127.

- Da, C.J.; Vitorino, R.; Silva, G.M.; Vogel, C.; Duarte, A.C.; Rocha-Santos, T. A synopsis on aging-Theories, mechanisms and future prospects. Ageing Res. Rev. 2016, 29, 90–112.

- Kraig, E.; Linehan, L.A.; Liang, H.; Romo, T.Q.; Liu, Q.; Wu, Y.; Benavides, A.D.; Curiel, T.J.; Javors, M.A.; Musi, N.; et al. A randomized control trial to establish the feasibility and safety of rapamycin treatment in an older human cohort: Immunological, physical performance, and cognitive effects. Exp. Gerontol. 2018, 105, 53–69.

- de Kreutzenberg, S.V.; Ceolotto, G.; Cattelan, A.; Pagnin, E.; Mazzucato, M.; Garagnani, P.; Borelli, V.; Bacalini, M.G.; Franceschi, C.; Fadini, G.P.; et al. Metformin improves putative longevity effectors in peripheral mononuclear cells from subjects with prediabetes. A randomized controlled trial. Nutr. Metab. Carbiovasc. Dis. 2015, 25, 686–693.

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, S. The Role of Rapamycin in Healthspan Extension via the Delay of Organ Aging. Ageing Res. Rev. 2021, 70, 101376.

- Hu, D.; Xie, F.; Xiao, Y.; Lu, C.; Zhong, J.; Huang, D.; Chen, J.; Wei, J.; Jiang, Y.; Zhong, T. Metformin: A Potential Candidate for Targeting Aging Mechanisms. Aging Dis. 2021, 12, 480–493.

- Li, J.; Kim, S.G.; Blenis, J. Rapamycin: One drug, many effects. Cell Metab. 2014, 19, 373–379.

- Soukas, A.A.; Hao, H.; Wu, L. Metformin as Anti-Aging Therapy: Is It for Everyone? Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2019, 30, 745–755.

- Yu, Y.; Shen, M.; Song, Q.; Xie, J. Biological activities and pharmaceutical applications of polysaccharide from natural resources: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 183, 91–101.

- Hao, C.; Sun, M.; Wang, H.; Zhang, L.; Wang, W. Low molecular weight heparins and their clinical applications. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2019, 163, 21–39.

- Li, X.; Ma, L.; Zhang, L. Molecular basis for Poria cocos mushroom polysaccharide used as an antitumor drug in China. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2019, 163, 263–296.

- Wang, N.; Liu, J.; Xie, F.; Gao, X.; Ye, J.H.; Sun, L.Y.; Wei, R.; Ai, J. miR-124/ATF-6, a novel lifespan extension pathway of Astragalus polysaccharide in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Cell. Biochem. 2015, 116, 242–251.

- Yang, F.; Xiu, M.; Yang, S.; Li, X.; Tuo, W.; Su, Y.; He, J.; Liu, Y. Extension of Drosophila Lifespan by Astragalus polysaccharide through a Mechanism Dependent on Antioxidant and Insulin/IGF-1 Signaling. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2021, 2021, 6686748.

- Zhang, X.P.; Liu, J.; Xu, C.Y.; Wei, Q.; Li, J.; Wang, L.; Wang, J.W.; Wang, Y.P. Effect of Angelica sinensis polysaccharide on expression of telomere, telomerase and P53 in mice aging hematopoietic stem cells. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi 2013, 38, 2354–2358.

- Mo, Z.Z.; Lin, Z.X.; Su, Z.R.; Zheng, L.; Li, H.L.; Xie, J.H.; Xian, Y.F.; Yi, T.G.; Huang, S.Q.; Chen, J.P. Angelica sinensis Supercritical Fluid CO2 Extract Attenuates D-Galactose-Induced Liver and Kidney Impairment in Mice by Suppressing Oxidative Stress and Inflammation. J. Med. Food 2018, 21, 887–898.

- Cheng, X.; Yao, H.; Xiang, Y.; Chen, L.; Xiao, M.; Wang, Z.; Xiao, H.; Wang, L.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y. Effect of Angelica polysaccharide on brain senescence of Nestin-GFP mice induced by D-galactose. Neurochem. Int. 2019, 122, 149–156.

- Li, X.T.; Zhang, Y.K.; Kuang, H.X.; Jin, F.X.; Liu, D.W.; Gao, M.B.; Liu, Z.; Xin, X.J. Mitochondrial protection and anti-aging activity of Astragalus polysaccharides and their potential mechanism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012, 13, 1747–1761.

- Hui, H.; Xin, A.; Cui, H.; Jin, H.; Yang, X.; Liu, H.; Qin, B. Anti-aging effects on Caenorhabditis elegans of a polysaccharide, O-acetyl glucomannan, from roots of Lilium davidii var. unicolor Cotton. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 155, 846–852.

- Finkel, T.; Holbrook, N.J. Oxidants, oxidative stress and the biology of ageing. Nature 2000, 408, 239–247.

- Mu, S.; Yang, W.; Huang, G. Antioxidant activities and mechanisms of polysaccharides. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2021, 97, 628–632.

- Kong, Y.; Trabucco, S.E.; Zhang, H. Oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction and the mitochondria theory of aging. Interdiscip. Top. Gerontol. 2014, 39, 86–107.

- Hui, Y.; Jun-li, H.; Chuang, W. Anti-oxidation and anti-aging activity of polysaccharide from Malus micromalus Makino fruit wine. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 121, 1203–1212.

- Zhu, Y.; Yu, X.; Ge, Q.; Li, J.; Wang, D.; Wei, Y.; Ouyang, Z. Antioxidant and anti-aging activities of polysaccharides from Cordyceps cicadae. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 157, 394–400.

- Doan, V.M.; Chen, C.; Lin, X.; Nguyen, V.P.; Nong, Z.; Li, W.; Chen, Q.; Ming, J.; Xie, Q.; Huang, R. Yulangsan polysaccharide improves redox homeostasis and immune impairment in D-galactose-induced mimetic aging. Food Funct. 2015, 6, 1712–1718.

- Ou, H.L.; Schumacher, B. DNA damage responses and p53 in the aging process. Blood 2018, 131, 488–495.

- Dutto, I.; Tillhon, M.; Cazzalini, O.; Stivala, L.A.; Prosperi, E. Biology of the cell cycle inhibitor p21(CDKN1A): Molecular mechanisms and relevance in chemical toxicology. Arch. Toxicol. 2015, 89, 155–178.

- Roitenberg, N.; Bejerano-Sagie, M.; Boocholez, H.; Moll, L.; Marques, F.C.; Golodetzki, L.; Nevo, Y.; Elami, T.; Cohen, E. Modulation of caveolae by insulin/IGF-1 signaling regulates aging of Caenorhabditis elegans. Embo Rep. 2018, 19, e45673.

- Sen, I.; Zhou, X.; Chernobrovkin, A.; Puerta-Cavanzo, N.; Kanno, T.; Salignon, J.; Stoehr, A.; Lin, X.; Baskaner, B.; Brandenburg, S.; et al. DAF-16/FOXO requires Protein Phosphatase 4 to initiate transcription of stress resistance and longevity promoting genes. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 138.

- Zhang, Y.; Lv, T.; Li, M.; Xue, T.; Liu, H.; Zhang, W.; Ding, X.; Zhuang, Z. Anti-aging effect of polysaccharide from Bletilla striata on nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Pharmacogn. Mag. 2015, 11, 449–454.

- Yuan, Y.; Kang, N.; Li, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Tan, P. Study of the Effect of Neutral Polysaccharides from Rehmannia glutinosa on Lifespan of Caenorhabditis elegans. Molecules 2019, 24, 4592.

- Huelsken, J.; Birchmeier, W. New aspects of Wnt signaling pathways in higher vertebrates. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2001, 11, 547–553.

- Maiese, K.; Li, F.; Chong, Z.Z.; Shang, Y.C. The Wnt signaling pathway: Aging gracefully as a protectionist? Pharmacol. Ther. 2008, 118, 58–81.

- Lezzerini, M.; Budovskaya, Y. A dual role of the Wnt signaling pathway during aging in Caenorhabditis elegans. Aging Cell 2014, 13, 8–18.

- Weng, N.P. Aging of the immune system: How much can the adaptive immune system adapt? Immunity 2006, 24, 495–499.

- Zhang, W.; Hwang, J.; Park, H.B.; Lim, S.M.; Go, S.; Kim, J.; Choi, I.; You, S.; Jin, J.O. Human Peripheral Blood Dendritic Cell and T Cell Activation by Codium fragile Polysaccharide. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 535.

- Budamagunta, V.; Manohar-Sindhu, S.; Yang, Y.; He, Y.; Traktuev, D.O.; Foster, T.C.; Zhou, D. Senescence-associated hyper-activation to inflammatory stimuli in vitro. Aging (Albany NY). 2021, 13, 19088–19107.

- Uribarri, J.; Cai, W.; Peppa, M.; Goodman, S.; Ferrucci, L.; Striker, G.; Vlassara, H. Circulating Glycotoxins and Dietary Advanced Glycation Endproducts: Two Links to Inflammatory Response, Oxidative Stress, and Aging. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 2007, 62, 427–433.

- Gautieri, A.; Passini, F.S.; Silván, U.; Guizar-Sicairos, M.; Carimati, G.; Volpi, P.; Moretti, M.; Schoenhuber, H.; Redaelli, A.; Berli, M.; et al. Advanced glycation end-products: Mechanics of aged collagen from molecule to tissue. Matrix Biol. 2017, 59, 95–108.

- Kim, M.T.; Harty, J.T. Impact of inflammatory cytokines on effector and memory CD8+T cells. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 295.

- Kale, A.; Sharma, A.; Stolzing, A.; Desprez, P.Y.; Campisi, J. Role of immune cells in the removal of deleterious senescent cells. Immun. Ageing 2020, 17, 16.

- Ren, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, T. Immunomodulatory activities of polysaccharides from Ganoderma on immune effector cells. Food Chem. 2021, 340, 127933.

- Xia, J.Y.; Fan, Y.L.; Jia, D.Y.; Zhang, M.S.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Li, J.; Jing, P.W.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.P. Protective effect of Angelica sinensis polysaccharide against liver injury induced by D-galactose in aging mice and its mechanisms. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi 2016, 24, 214–219.

- Jacczak, B.; Rubis, B.; Toton, E. Potential of Naturally Derived Compounds in Telomerase and Telomere Modulation in Skin Senescence and Aging. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6381.

- de Lange, T. Shelterin-Mediated Telomere Protection. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2018, 52, 223–247.

- Zhang, F.; Song, X.; Li, L.; Wang, J.; Lin, L.; Li, C.; Li, H.; Lv, Y.; Jin, Y.; Liu, Y.; et al. Polygala tenuifolia polysaccharide (PTP) inhibits cell proliferation by repressing Bmi-1 expression and downregulating telomerase activity. Tumour Biol. 2015, 36, 2907–2912.

- Han, M.H.; Lee, D.S.; Jeong, J.W.; Hong, S.H.; Choi, I.W.; Cha, H.J.; Kim, S.; Kim, H.S.; Park, C.; Kim, G.Y.; et al. Fucoidan Induces ROS-Dependent Apoptosis in 5637 Human Bladder Cancer Cells by Downregulating Telomerase Activity via Inactivation of the PI3K/Akt Signaling Pathway. Drug Dev. Res. 2017, 78, 37–48.

More

Information

Subjects:

Biochemistry & Molecular Biology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.2K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

26 Dec 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No