Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Swarna Jaiswal | -- | 2820 | 2022-12-22 12:53:15 | | | |

| 2 | Camila Xu | Meta information modification | 2820 | 2022-12-22 14:37:26 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Perera, K.Y.; Prendeville, J.; Jaiswal, A.K.; Jaiswal, S. Cold Plasma Technology in Food Packaging. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/39093 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Perera KY, Prendeville J, Jaiswal AK, Jaiswal S. Cold Plasma Technology in Food Packaging. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/39093. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Perera, Kalpani Y., Jack Prendeville, Amit K. Jaiswal, Swarna Jaiswal. "Cold Plasma Technology in Food Packaging" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/39093 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Perera, K.Y., Prendeville, J., Jaiswal, A.K., & Jaiswal, S. (2022, December 22). Cold Plasma Technology in Food Packaging. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/39093

Perera, Kalpani Y., et al. "Cold Plasma Technology in Food Packaging." Encyclopedia. Web. 22 December, 2022.

Copy Citation

Cold plasma (CP) is an effective strategy to alter the limitations of biopolymer materials for food packaging applications. Biopolymers such as polysaccharides and proteins are known to be sustainable materials with excellent film-forming properties.

cold plasma

sustainable food packaging

biopolymer modification

1. Introduction

Conventional thermal processing including pasteurisation, sterilisation, canning, steaming, drying, evaporation, frying, cooking, baking, and blanching has remained at the forefront of the food industry for providing safe quality food, inhibiting pathogenic microorganisms, and improving nutrition [1]. Despite being the relied-upon method, conventional thermal processing leads to a significant decline in the quality of food. Thermal processing reduces the nutritional content by decreasing vitamin content, lowering the biological value of proteins, enhancing lipid oxidation, and depleting the sensory attributes of food [2]. Due to these disadvantages and increased consumer awareness around safe food, novel processing methods such as non-thermal processing including ultraviolet light, ultrasound, irradiation, cold plasma (CP), high pressure processing, and pulsed electric field are emerging technologies [3]. These new non-thermal technologies eliminate heat from processing which leads to better retention of nutrients, and better sensory attributes while inhibiting the growth of microorganisms [3]. Non-thermal processing sterilises food by altering the cell membrane or destroying the genetic material of microorganisms [3]. Despite offering great benefits, non-thermal processing has yet to become established within the food industry and remains in the developmental stage. According to a survey conducted by Khouryieh [4], it was found that high pressure processing was the most established (35.6%) novel processing method within the food industry while atmospheric cold plasma (ACP) only had an applied usage of 2%. The major limitation of implementing these technologies is the high-cost evolvement. In addition, the effectiveness of these emerging technologies is not yet capable of matching that of traditional methods [4].

CP technology is a novel non-thermal processing method that is gaining interest within the food industry and is particularly effective in the reduction of microbial loads within a short period of time, especially in fresh fruits and meats [5]. The method provides additional beneficial outcomes such as decontamination of packaging materials, a more sustainable method, and limits browning in foods [6].

2. CP Technology in the Food Industry

The fourth state of matter, known as plasma, can be seen as an arc or discharge of intense fluorescent light [7]. A mixture of reactive species including electrons, photons, positively or negatively charged ions, free radicals, and atoms in their excited and ground states make up plasma, which is a partially or entirely ionised gas [8]. Plasma has a net neutral charge and is referred to as quasineutral. Plasma is created under various temperatures by ionising a neutral gas and can be classified into thermal and non-thermal plasma. The generation of thermal plasma requires a high pressure above 105 Pa and an electrical supply greater than 50 MV. Non-thermal plasma can exist without a localised thermodynamic equilibrium and does not require high pressure or power [8].

Non-thermal plasma can be subdivided into two categories:

-

Quasiequilibrium plasma (50–100 °C), where the reactive species are in local thermodynamic equilibrium

-

Nonequilibrium plasma (<60 °C) or CP where the heavier species present have a lower temperature than the electrons.

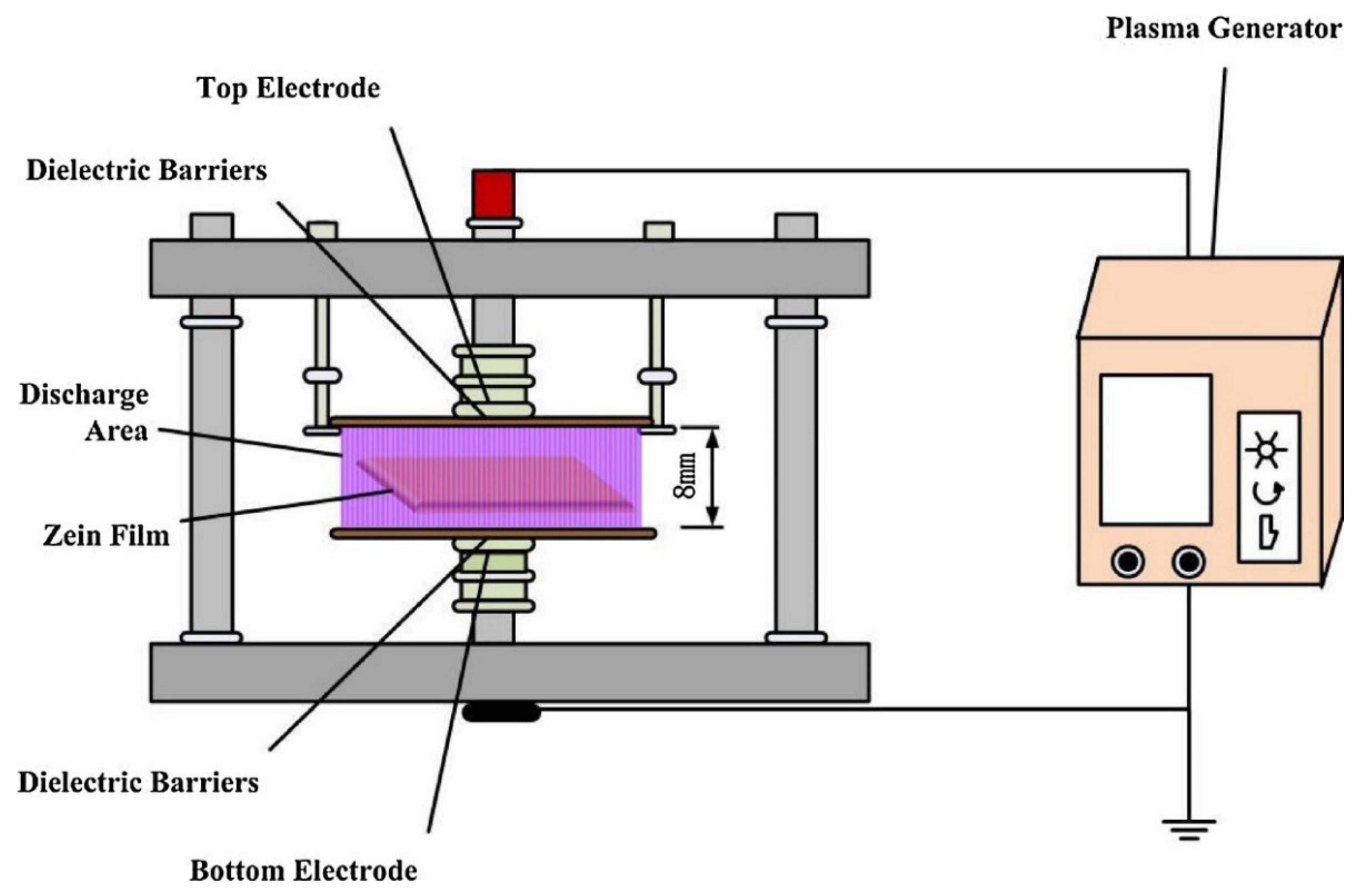

Nonequilibrium plasma or CP is generated at atmospheric pressure upon application of an electric field to a neutral gas. Direct current or alternate current is applied to the neutral gas between two electrode plates at a set frequency (Figure 1). The stages of CP generation involve excitation, ionisation, and dissociation [9]. The reactive species found in plasma are effective against a range of pathogenic microorganisms such as bacteria, fungi, and viruses as well as pesticides and mycotoxins. CP is a promising technology for non-thermal sterilisation and the development of bio-based food packaging materials. CP allows for modification of previously unsuitable biopolymers to create packaging materials with the desired applicability. There have been modifications to the wettability, sealability, printability, adhesion, and mechanical properties [10][11].

Figure 1. Schematic diagram of Dielectric Barrier Discharge (DBD) for CP treatment [12].

CP technology could be beneficial within the food industry if it is applied on an industrial scale as it has recently shown great capabilities such as a reduction in spoilage, degradation of mycotoxins, inactivation of enzymes, increased bioactive compounds, improvement antioxidants, and reduced allergenicity [13]. The technology has been reported to be effective at eliminating mycotoxins commonly found in seeds, grains, and crops due to high oxidation rates [14]. In terms of enzymes, it has shown to be effective at the inactivation of enzymes peroxidase and polyphenol oxidase which are responsible for enzymatic browning in fruits [14]. In relation to bioactive components, CP can reduce germination rates in brown rice leading to an accumulation of the maximum number of bioactive phytochemicals [15]. By means of allergens, it has been reported by Bourke et al. [14] that CP can reduce the immune reactivity of proteins in soybeans through direct and indirect exposure. In the dairy sector, CP is used as a rapid, non-thermal method of pasteurising milk to maintain milk quality while ensuring food safety [16]. It has been proven by the studies of [17][18] that non-thermal CP can be used as a method of milk pasteurisation with effective microbial reduction.

3. CP in Food Packaging

CP technology can also be applied to food packaging during washing through spray form preventing contamination and any unwanted growth of microorganisms [6]. Most packaging materials used in the food industry cannot withstand heat such as polyethylene terephthalate (PET). The possible use of CP is demonstrated by [19] not damaging the structures of the packaging materials as it is operated under low temperatures. It is also highly effective as it eliminates cross-contamination that usually occurs between the application of microbial limiting treatments and the packaging process of the food product [20]. In recent studies, CP treatments applied to food packages containing cabbages slices [21], Korean rice cakes [20], and fish cakes [22] all demonstrated the effectiveness of reducing bacterial loads, especially Salmonella spp. by applying in-package treatments. It has also shown its ability to alter the structure of cellulose compounds leading to a better breakdown which may improve the development of edible films in food packaging [23]. The preservation of fruits postharvest is difficult to maintain however ACP can be used as a preventative measure in inhibiting decay and has been seen to be successful in blueberries [24]. Further, CP technology has recently been applied to many food products and shows promising effects on food packaging decontamination which could have the potential to revolutionise traditional conventional methods within the food industry.

3.1. Impact of CP on Food Packaging Surface Sterilisation

Research suggests CP is a promising method of food packaging surface sterilisation as it is quick and induces no negative alterations to the functionality of the packaging materials. The food packaging process is considered a critical control point as part of the Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points plan [25]. The conventional methods of sterilising food packaging include dry heat, steam, UV, and chemicals (ethylene oxide and hydrogen peroxide). Heat generating methods are a concern for certain materials such as PET, which is a temperature sensitive compound. Chemical methods of sterilisation may present health risks due to toxicity, mishandling, residue, and environmental hazards. To lower costs and avoid thermal approaches and the generation of chemical effluent, CP has been investigated as an alternative approach to packaging sterilisation. CP does not generate residue, is chemical free, safe, and applies to a range of packaging materials [19]. Muranyi et al. [26] used CP to sterilise PET packaging and other multilayer packaging materials consisting of polyvinylidene chloride (and low density polyethylene (LDPE). They achieved a 2log10 reduction in Aspergillus niger and Bacillus subtilis with an exposure time of 1 s. Lee et al. [27] treated glass, polyethylene (PE), polypropylene (PP), nylon, and paper foil packaging varieties using CP, inactivation of Escherichia coli O157:H7, Salmonella typhimurium, Staphylococcus aureus was observed. Yang et al. [28] used glow discharge plasma to sterilise PET sheets. The treatment induced a germicidal effect, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa was completely inactivated within 30 s.

3.2. Impact of CP on Modification of Food Packaging Polymers

Polymeric packaging materials such as PET, PE, PP, polyvinyl chloride, and polystyrene are the common plastics utilised in the food industry. Polymers are a major contributor to the packaging industry accounting for two third of the total plastics produced [29]. Polymer packaging materials offer many benefits however their hydrophobicity and low surface energy leads to necessary surface alterations needed to obtain desirable packaging features [30]. The conventional chemical methods of modifying food packaging generate waste leading to a negative effect on the environment, however, with novel methods such as CP treatments, there is no waste generated resulting in a more sustainable solution to food packaging modification [30].

CP impacts food packaging by increasing polymer energy, modifying the surface, and increasing adhesiveness for printing and seals [13]. The impact of surface modification can be altered by different plasma configurations and electrode materials [13]. The alteration occurs after the formation of plasma whereby the active species formed lead to physical and chemical interactions on the surface of a polymer resulting in a modification of its properties including roughness, functionality, wettability, barrier function, antimicrobial, and biodegradability.

PE naturally has low surface energy which can be modified through CP treatments to produce higher surface energy, this material is mainly used within films or coatings [31]. In recent literature, PE has been applied as a nano fibrillated cellulose film [32], an LDPE bilayer film with summer savory essential oil [33], and an LDPE film coated with gallic acid [34]. The antimicrobial activity of the material in combination with CP has been proven to be effective against certain bacteria including Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus [34], however, there is no reduction reported for Listeria monocytogenes [31]. In terms of barrier functions, the material in combination with CP has been reported in many studies to improve oxygen barrier function [32] and decrease water vapour permeability (WVP) [33]. The application of CP on LDPE increases surface roughness (SR) effectively which enhances the ability to coat the material with preservatives [34]. The material in combination with CP improves adhesion due to increased production of polar groups and increases tensile strength (TS) [33]. These beneficial outcomes are dependent upon the amount of electrical energy used and the length of the application as certain alternations of these two factors could lead to negative outcomes.

PET can be used in a variety of forms including in-package treatments, films, and foils, in recent literature the material has been used for albumin/gelatin film plates [35], bilayer films with surface CP pretreatments and in-package treatments for cabbage slices [21], chicken breast [36] and fish cakes [22]. In terms of benefits, the material has shown great adherence to microbial inhibition as it has been proven to eliminate numerous bacteria including Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Salmonella spp., and Salmonella typhimurium [19]. In a study by Kim and Min, cabbage slices stored within PET containers observed a 0.9 log CFU g−1 reduction in Salmonella after 3 min of CP treatments [21]. However, in another study on fish cakes by Lee et al. [22] Salmonella growth reduction was greater between 1.3–1.4 log CFU g−1. The material has also been deemed effective in combination with CP in reducing the fungus Penicillium digitatum which generally impacts mandarin oranges [37]. In terms of disadvantages, due to PET being hydrophobic in nature and obtaining low density polar functional groups the material is predisposed to poor dye adhesion, poor particles, and microparticles [38]. The ability to transfer ink onto the material is low creating printing constraints. CP treatments offer a solution to these issues as the application increases water permeability for PET materials improving wettability properties without chemical alteration [39].

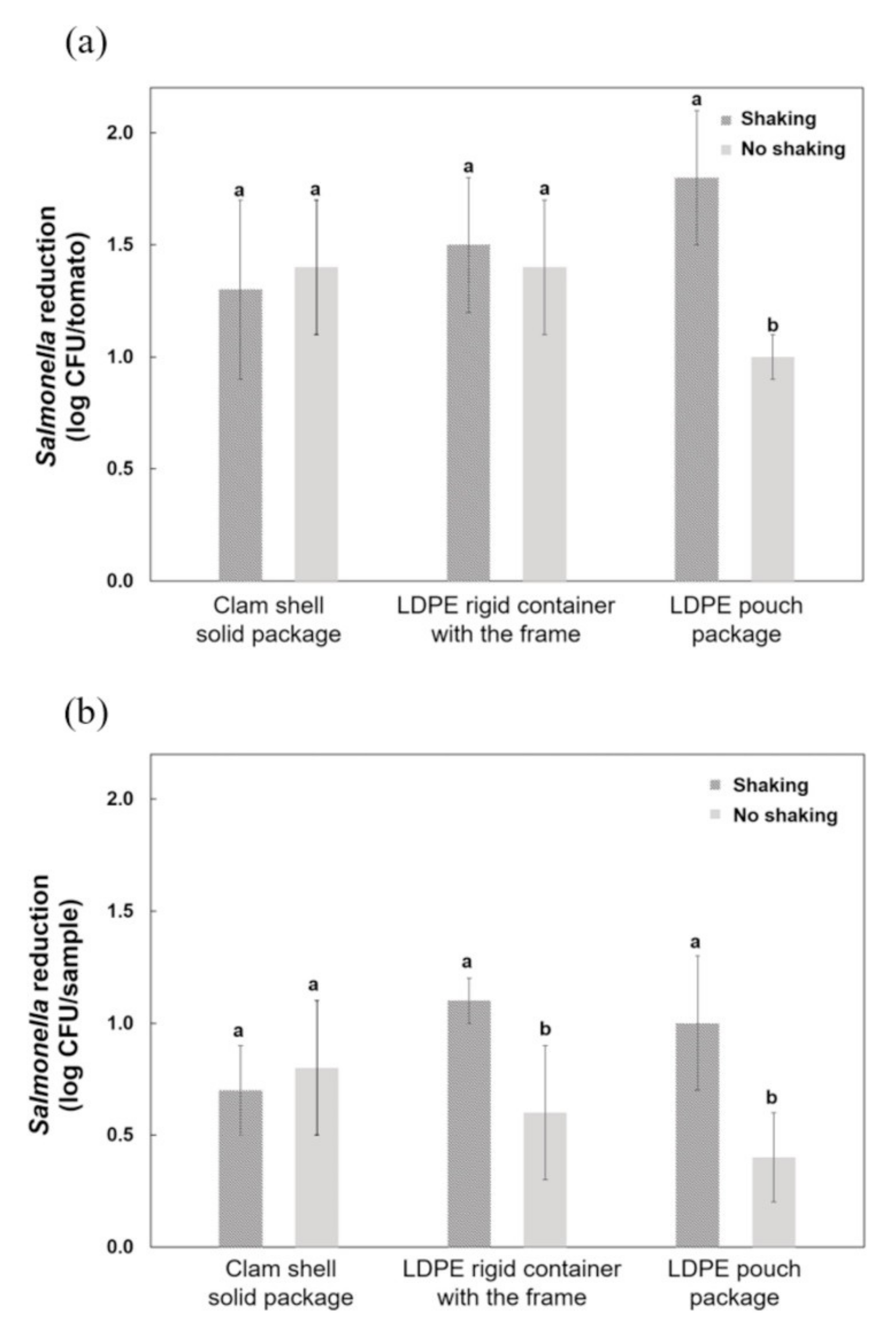

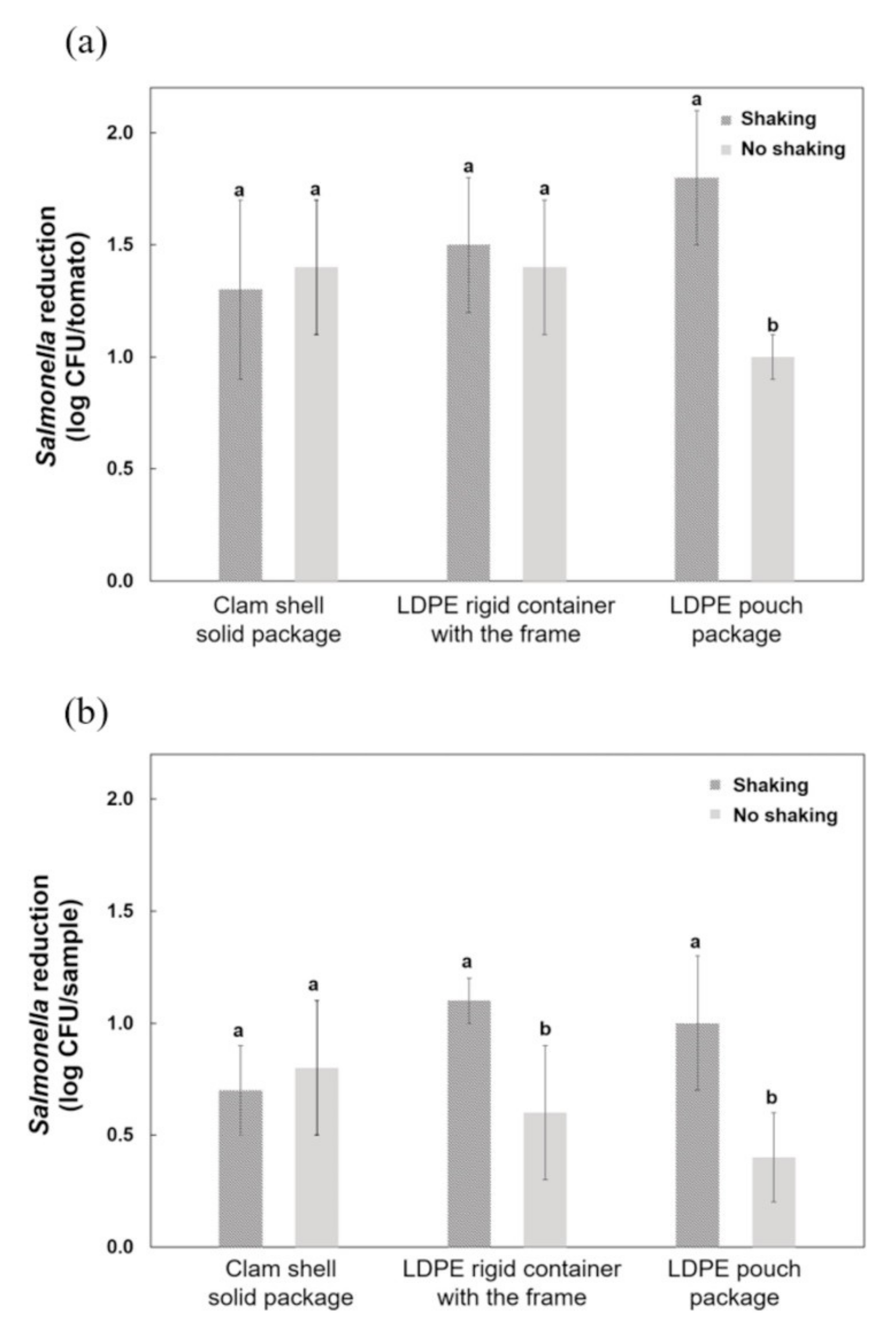

In a study conducted by Kim et al. [40] the use of LDPE and PET packaging is compared in terms of microbial inactivation, the use of shaking, positioning, WVP, tensile strength, and opacity. In terms of sterilisation effects, LDPE packaging offered better microbial inhibition for mesophilic aerobic bacteria on grape tomatoes compared to PET packaging [40]. Microbial inhibition depends upon the packaging material’s dielectric permittivity as it creates different stages of micro discharges leading to different amounts of reactive species produced during CP treatments [40]. For example, LDPE has a lower dielectric permittivity compared to PET resulting in a higher inactivation rate of bacteria as observed in this research [40]. Other factors influence microbial inhibition such as shaking and positioning of the packages. Shaking of packages before CP treatments eliminates inaccuracies as it develops contact between reactive species improving microbial inhibition [40]. There was a higher microbial inactivation rate for Salmonella at 0.4 log CFU tomato−1 observed for grape tomatoes when shaking was applied. In Figure 2, it is clear that there is a higher microbial inactivation rate when shaking of LDPE packaging is applied.

Figure 2. The effect shaking has under DBD ADCP treatment on (a) grape tomatoes (b) slices of romaine lettuce, red cabbage, and carrot with clamshell solid packages, LDPE rigid containers and the LDPE pouch package. The letters indicate significant differences at p < 0.05. Reprinted with permission from ref. [40]. Copyright 2022 Elsevier.

The position of packages in line with the electrodes determines the reactive species formed which also has a direct effect on microbial inhibition [40]. The water vapour barrier (WVP), TS, and opacity increased when PET and LDPE were treated under CP technology. This research shows how the two polymeric packaging materials can be applied to create beneficial effects in combination with CP treatments.

In terms of safety and quality aspects, there must be testing completed on CPs effects on food packaging materials such as PET and PE to ensure it is within migratory limits and to assess permeability associated with water vapour and O2 [41].

3.3. Impact of CP on Biopolymer-Based Packaging Materials

In comparison to plastics, biopolymers are known to exhibit inferior mechanical properties, low thermal stability, poor surface functionality, poor printability, and low adhesiveness [9].

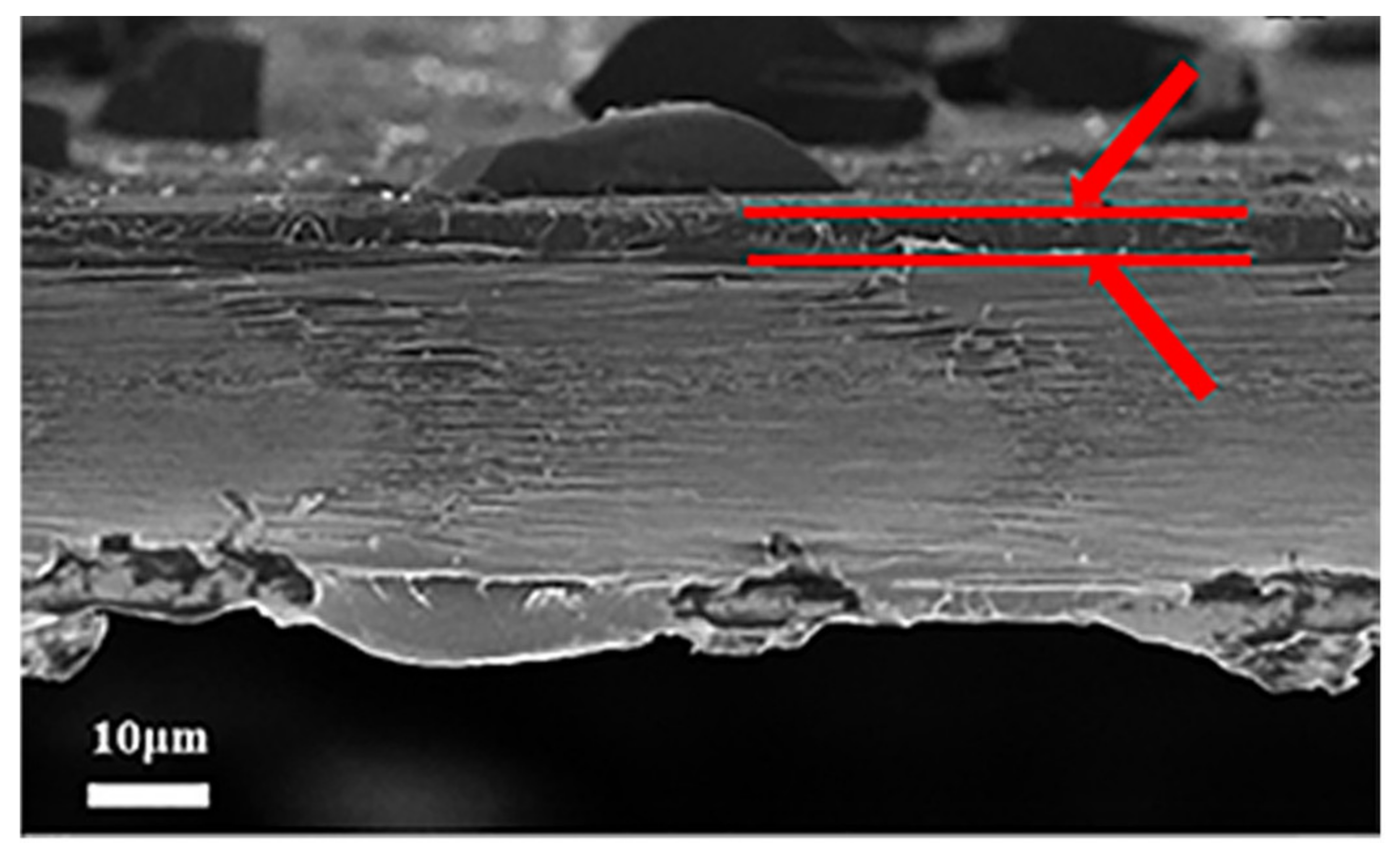

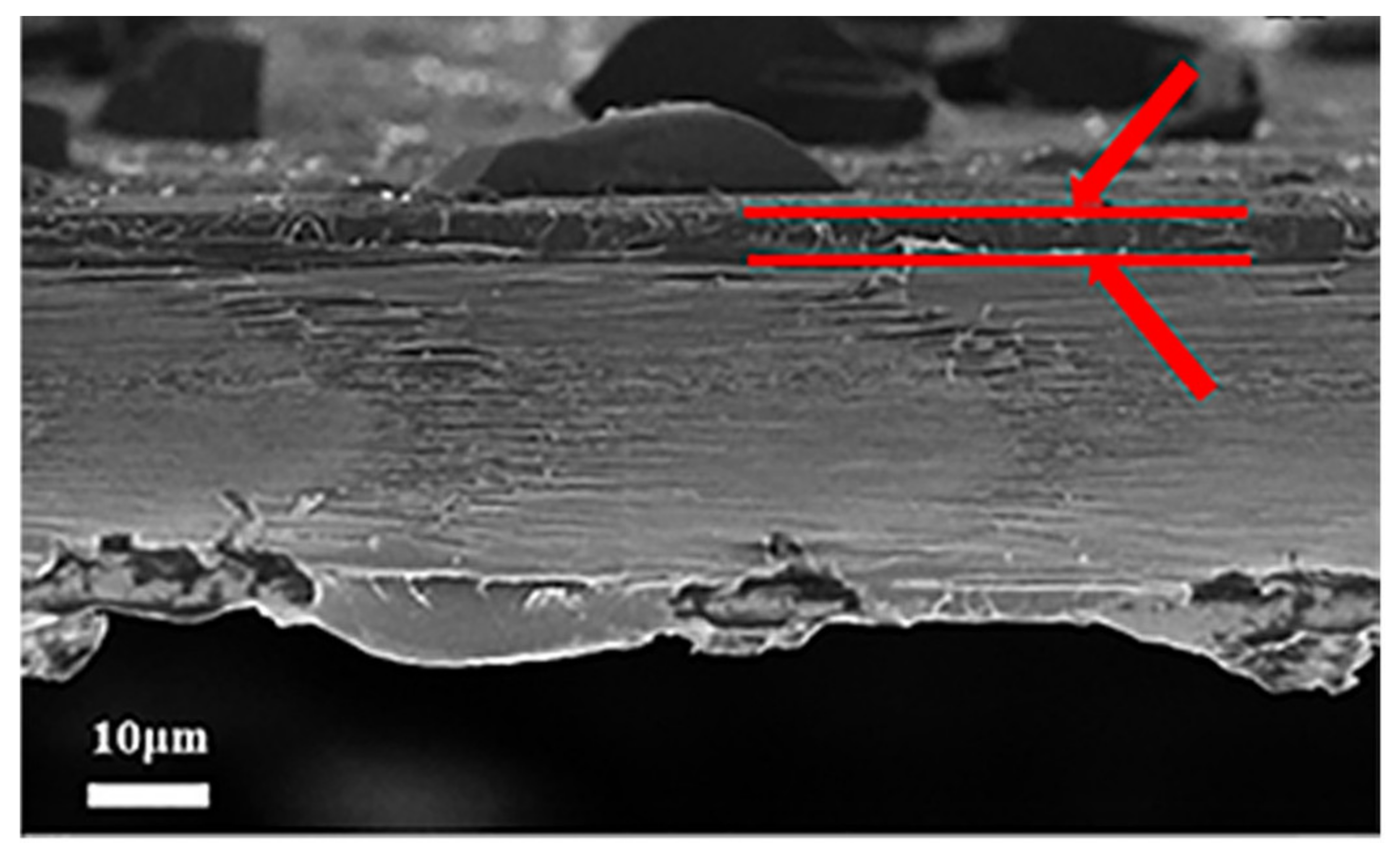

Polylactic acid (PLA) is well suited as a packaging material due to its biodegradability, affordability, transparency, processability, and plastic like mechanical properties [42]. PLA in its pristine state is brittle and therefore poses challenges as a packaging material. Literature suggests PLA can be reengineered using CP to combine it with other materials such as nisin, metal oxide nanoparticles, and graphite [42]. Hu et al. [42] created an antimicrobial food packaging by coating a PLA film with nisin. CP treatment facilitated adhesion between the two layers (Figure 3) and is effective against an array of Gram-positive bacteria including Listeria monocytogenes. Enhanced antimicrobial activity, gas barrier properties, and more suitable surface morphology were observed when CP was employed to combine the two materials.

Figure 3. CP treatment effectively facilitated the grafting of nisin onto PLA film. Reprinted with permission from ref. [42]. Copyright John Wiley and Sons 2022.

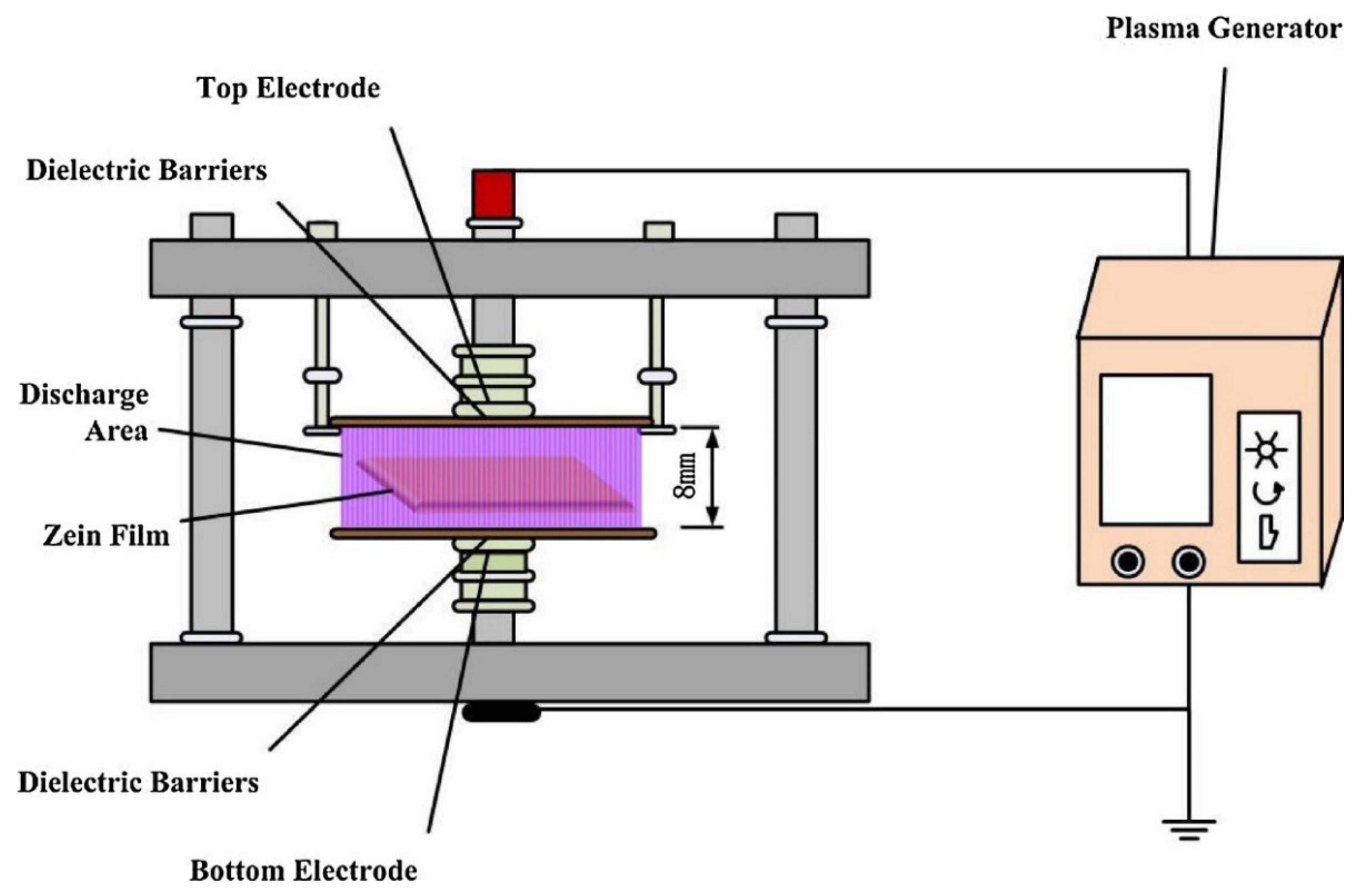

Zein is hydrophobic and is therefore insoluble in water, it can be dissolved using ethanol or acetone. Zein films exhibit a glossy appearance, low permeability, biodegradability, and grease proof properties. It is challenging to layer a hydrophobic material onto another hydrophobic material due to the lack of polar groups. To overcome this, CP can activate the surface layer of hydrophobic materials. Plasma discharge can create polar containing groups on the surface layer, enabling interface adhesion between two hydrophobic materials [43]. Contact of zein to CP treatment for the 60 s before layering onto PLA film, enhanced hydrophobicity (by 24.1%), TS (by 50.5%), EAB (by 29.7%), and WVP (by 44.3%) in comparison to the untreated film [43]. The multilayer films showed good biodegradability and UV barrier properties. Chen et al. [43] concluded that the approach of layering a PLA coating onto zein film created a packaging material with the desired application for use in the biodegradable packaging industry. Similarly, Dong et al. [44] enhanced the water resistance properties of the zein based film by exposure to CP (Figure 4) which sequentially facilitated grafting to PCL.

Figure 4. Representation of the experimental setup for treatment of zein films with ACP. Reprinted with permission from ref. [30]. Copyright Elsevier 2022.

Pectin is a biopolymer that is used in food packaging due to its exceptional mechanical properties, biocompatibility, biodegradability, and nontoxicity. The use of CP in combination with other bioactive chemicals has been used to improve the functionality of biopolymeric films. The aim of Jahromi et al. [45] developed pectin films with antioxidant activity by including clove essential oil emulsions stabilised by CP. A DBD device was used for the CP treatment for 5 min at a frequency of 10 kHz and a voltage of 7 kV (28 °C, 34% RH). The films had improved mechanical strength, stretchability, surface hydrophobicity, and clove essential oil retention during storage.

Studies on CP treatment in food packaging for other biopolymers such as chitosan and starch have also been performed by Sheikhi et al. [46]. Chitosan and starch are both nontoxic biopolymers that are biocompatible, and biodegradable. However, they both have poor mechanical qualities, which are significantly improved when both biopolymers are combined. For the further increment of the mechanical properties, CP treatment is carried out. Sheikhi et al. [46] investigated the mechanical and physical properties of a starch-chitosan composite film exposed to low pressure air and argon plasma at 600 mTorr for various time points (4, 8, and 12 min) and assessed the shelf life of chicken breast fillet packaged with plasma treated films. After 12 min of processing, it was observed that argon plasma is more effective at increasing the TS of the films, increased from 10.59 to 22.09 MPa. Nevertheless, the CP treatment did not prolong the shelf-life of the fillets.

References

- Knorr, D.; Augustin, M.A. Food Processing Needs, Advantages and Misconceptions. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 108, 103–110.

- Fellows, P.J. Food Processing Technology: Principles and Practice, 3rd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 1–913.

- Zhuang, H.; Rothrock, M.J.; Hiett, K.L.; Lawrence, K.C.; Gamble, G.R.; Bowker, B.C.; Keener, K.M.; Šerá, B. In-Package Air Cold Plasma Treatment on Chicken Breast Meat: Treatment Time Effect. J. Food Qual. 2019, 2019, 1s837351.

- Khouryieh, H.A. Novel and Emerging Technologies Used by the U.S. Food Processing Industry. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2021, 67, 102559.

- Ganesan, A.R.; Tiwari, U.; Ezhilarasi, P.N.; Rajauria, G. Application of Cold Plasma on Food Matrices: A Review on Current and Future Prospects. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2021, 45, e15070.

- Ucar, Y.; Ceylan, Z.; Durmus, M.; Tomar, O.; Cetinkaya, T. Application of Cold Plasma Technology in the Food Industry and Its Combination with Other Emerging Technologies. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 114, 355–371.

- Pankaj, S.K.; Bueno-Ferrer, C.; Misra, N.N.; O’Neill, L.; Tiwari, B.K.; Bourke, P.; Cullen, P.J. Physicochemical Characterisation of Plasma-Treated Sodium Caseinate Film. Food Res. Int. 2014, 66, 438–444.

- Wanigasekara, J.; Barcia, C.; Cullen, P.J.; Tiwari, B.; Curtin, J.F. Plasma induced reactive oxygen species-dependent cytotoxicity in glioblastoma 3D tumourspheres. Plasma Process. Polym. 2022, 19, e2100157.

- Hoque, M.; McDonagh, C.; Tiwari, B.K.; Kerry, J.P.; Pathania, S. Effect of Cold Plasma Treatment on the Packaging Properties of Biopolymer-Based Films: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1346.

- Bahrami, R.; Zibaei, R.; Hashami, Z.; Hasanvand, S.; Garavand, F.; Rouhi, M.; Jafari, S.M.; Mohammadi, R. Modification and Improvement of Biodegradable Packaging Films by Cold Plasma; a Critical Review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 1936–1950.

- Fazeli, M.; Florez, J.P.; Simão, R.A. Improvement in Adhesion of Cellulose Fibers to the Thermoplastic Starch Matrix by Plasma Treatment Modification. Compos. Part B Eng. 2019, 163, 207–216.

- Starič, P.; Vogel-Mikuš, K.; Mozetič, M.; Junkar, I. Effects of Nonthermal Plasma on Morphology, Genetics and Physiology of Seeds: A Review. Plants 2020, 9, 1736.

- Laroque, D.A.; Seó, S.T.; Valencia, G.A.; Laurindo, J.B.; Carciofi, B.A.M. Cold Plasma in Food Processing: Design, Mechanisms, and Application. J. Food Eng. 2022, 312, 110748.

- Bourke, P.; Ziuzina, D.; Boehm, D.; Cullen, P.J.; Keener, K. The Potential of Cold Plasma for Safe and Sustainable Food Production. Trends Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 615–626.

- Yodpitak, S.; Mahatheeranont, S.; Boonyawan, D.; Sookwong, P.; Roytrakul, S.; Norkaew, O. Cold Plasma Treatment to Improve Germination and Enhance the Bioactive Phytochemical Content of Germinated Brown Rice. Food Chem. 2019, 289, 328–339.

- Nikmaram, N.; Keener, K.M. The Effects of Cold Plasma Technology on Physical, Nutritional, and Sensory Properties of Milk and Milk Products. LWT 2022, 154, 112729.

- Kasih, T.P.; Mangindaan, D.; Ningrum, A.S.; Sebastian, C.; Widyaningrum, D. Bacterial Inactivation by Using Non Thermal Argon Plasma Jet and Its Application Study for Non Thermal Raw Milk Processing. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Banten, Indonesia, 10–11 November 2020; Volume 794, p. 012104.

- Dash, S.; Jaganmohan, R. Stability and Shelf-Life of Plasma Bubbling Treated Cow Milk. Int. J. Life Sci. Pharma Res. 2022, 12, L111–L120.

- Mandal, R.; Singh, A.; Pratap Singh, A. Recent Developments in Cold Plasma Decontamination Technology in the Food Industry. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 80, 93–103.

- Kang, J.H.; Jeon, Y.J.; Min, S.C. Effects of Packaging Parameters on the Microbial Decontamination of Korean Steamed Rice Cakes Using In-Package Atmospheric Cold Plasma Treatment. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2021, 30, 1535–1542.

- Kim, Y.E.; Min, S.C. Inactivation of Salmonella in Ready-to-Eat Cabbage Slices Packaged in a Plastic Container Using an Integrated in-Package Treatment of Hydrogen Peroxide and Cold Plasma. Food Control 2021, 130, 108392.

- Lee, H.S.; Kim, N.; Min, S.C. Inactivation of Salmonella in Steamed Fish Cake Using an In-Package Combined Treatment of Cold Plasma and Ultraviolet-Activated Zinc Oxide. Food Control 2022, 135, 108772.

- Zhu, H.; Han, Z.; Cheng, J.H.; Sun, D.W. Modification of Cellulose from Sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum) Bagasse Pulp by Cold Plasma: Dissolution, Structure and Surface Chemistry Analysis. Food Chem. 2022, 374, 131675.

- Hu, X.; Sun, H.; Yang, X.; Cui, D.; Wang, Y.; Zhuang, J.; Wang, X.; Ma, R.; Jiao, Z. Potential Use of Atmospheric Cold Plasma for Postharvest Preservation of Blueberries. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2021, 179, 111564.

- Pankaj, S.K.; Bueno-Ferrer, C.; Misra, N.N.; O’Neill, L.; Jiménez, A.; Bourke, P.; Cullen, P.J. Characterisation of Polylactic Acid Films for Food Packaging as Affected by Dielectric Barrier Discharge Atmospheric Plasma. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2014, 21, 107–113.

- Muranyi, P.; Wunderlich, J.; Langowski, H.C. Modification of Bacterial Structures by a Low-Temperature Gas Plasma and Influence on Packaging Material. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2010, 109, 1875–1885.

- Lee, T.; Puligundla, P.; Mok, C. Inactivation of Foodborne Pathogens on the Surfaces of Different Packaging Materials Using Low-Pressure Air Plasma. Food Control 2015, 51, 149–155.

- Yang, L.; Chen, J.; Gao, J.; Guo, Y. Plasma Sterilisation Using the RF Glow Discharge. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2009, 255, 8960–8964.

- Siracusa, V.; Blanco, I. Bio-Polyethylene (Bio-PE), Bio-Polypropylene (Bio-PP) and Bio-Poly(Ethylene Terephthalate) (Bio-PET): Recent Developments in Bio-Based Polymers Analogous to Petroleum-Derived Ones for Packaging and Engineering Applications. Polymers 2020, 12, 1641.

- Dong, S.; Guo, P.; Chen, Y.; Chen, G.Y.; Ji, H.; Ran, Y.; Li, S.H.; Chen, Y. Surface Modification via Atmospheric Cold Plasma (ACP): Improved Functional Properties and Characterisation of Zein Film. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 115, 124–133.

- Pankaj, S.K.; Bueno-Ferrer, C.; Misra, N.N.; Bourke, P.; Cullen, P.J. Zein Film: Effects of Dielectric Barrier Discharge Atmospheric Cold Plasma. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2014, 131, 40803.

- Lu, P.; Guo, M.; Xu, Z.; Wu, M. Application of Nanofibrillated Cellulose on BOPP/LDPE Film as Oxygen Barrier and Antimicrobial Coating Based on Cold Plasma Treatment. Coatings 2018, 8, 207.

- Moradi, E.; Moosavi, M.H.; Hosseini, S.M.; Mirmoghtadaie, L.; Moslehishad, M.; Khani, M.R.; Jannatyha, N.; Shojaee-Aliabadi, S. Prolonging Shelf Life of Chicken Breast Fillets by Using Plasma-Improved Chitosan/Low Density Polyethylene Bilayer Film Containing Summer Savory Essential Oil. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 156, 321–328.

- Wong, L.W.; Hou, C.Y.; Hsieh, C.C.; Chang, C.K.; Wu, Y.S.; Hsieh, C.W. Preparation of Antimicrobial Active Packaging Film by Capacitively Coupled Plasma Treatment. LWT 2020, 117, 108612.

- Pérez-Huertas, S.; Terpiłowski, K.; Tomczyńska-Mleko, M.; Mleko, S. Surface Modification of Albumin/Gelatin Films Gelled on Low-Temperature Plasma-Treated Polyethylene Terephthalate Plates. Plasma Process. Polym. 2020, 17, 1900171.

- Roh, S.H.; Lee, S.Y.; Park, H.H.; Lee, E.S.; Min, S.C. Effects of the Treatment Parameters on the Efficacy of the Inactivation of Salmonella Contaminating Boiled Chicken Breast by In-Package Atmospheric Cold Plasma Treatment. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2019, 293, 24–33.

- Bang, I.H.; Lee, E.S.; Lee, H.S.; Min, S.C. Microbial Decontamination System Combining Antimicrobial Solution Washing and Atmospheric Dielectric Barrier Discharge Cold Plasma Treatment for Preservation of Mandarins. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2020, 162, 111102.

- Sant’Ana, P.L.; Ribeiro Bortoleto, J.R.; da Cruz, N.C.; Rangel, E.C.; Durrant, S.F.; Costa Botti, L.M.; Rodrigues dos Anjos, C.A. Surface Properties of Low-Density Polyethylene Treated by Plasma Immersion Ion Implantation for Food Packaging. Rev. Bras. Apl. Vácuo 2020, 39, 14–23.

- Sandanuwan, T.; Hendeniya, N.; Attygalle, D.; Amarasinghe, D.A.S.; Weragoda, S.C.; Samarasekara, A.M.P.B. Atmospheric Cold Plasma to Improve Printability of Polyethylene Terephthalate. In Proceedings of the MERCon 2021-7th International Multidisciplinary Moratuwa Engineering Research Conference, Moratuwa, Sri Lanka, 27–29 July 2021; pp. 654–658.

- Kim, S.Y.; Bang, I.H.; Min, S.C. Effects of Packaging Parameters on the Inactivation of Salmonella Contaminating Mixed Vegetables in Plastic Packages Using Atmospheric Dielectric Barrier Discharge Cold Plasma Treatment. J. Food Eng. 2019, 242, 55–67.

- Misra, N.N.; Yepez, X.; Xu, L.; Keener, K. In-Package Cold Plasma Technologies. J. Food Eng. 2019, 244, 21–31.

- Hu, S.; Li, P.; Wei, Z.; Wang, J.; Wang, H.; Wang, Z. Antimicrobial Activity of Nisin-Coated Polylactic Acid Film Facilitated by Cold Plasma Treatment. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2018, 135, 46844.

- Chen, G.; Dong, S.; Zhao, S.; Li, S.; Chen, Y. Improving Functional Properties of Zein Film via Compositing with Chitosan and Cold Plasma Treatment. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 129, 318–326.

- Dong, S.; Guo, P.; Chen, G.-Y.; Jin, N.; Chen, Y. Study on the Atmospheric Cold Plasma (ACP) Treatment of Zein Film: Surface Properties and Cytocompatibility. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 153, 1319–1327.

- Jahromi, M.; Niakousari, M.; Golmakani, M.T. Fabrication and Characterisation of Pectin Films Incorporated with Clove Essential Oil Emulsions Stabilised by Modified Sodium Caseinate. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2022, 32, 100835.

- Sheikhi, Z.; Mirmoghtadaie, L.; Abdolmaleki, K.; Khani, M.R.; Farhoodi, M.; Moradi, E.; Shokri, B.; Shojaee-Aliabadi, S. Characterisation of Physicochemical and Antimicrobial Properties of Plasma-Treated Starch/Chitosan Composite Film. Packag. Technol. Sci. 2021, 34, 385–392.

More

Information

Subjects:

Food Science & Technology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.7K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

22 Dec 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No