Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sivakumar Swaminathan | -- | 1721 | 2022-12-21 16:51:36 | | | |

| 2 | Conner Chen | + 2 word(s) | 1723 | 2022-12-22 05:01:57 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Swaminathan, S.; Lionetti, V.; Zabotina, O.A. CW Integrity Systems Involved in Plant Biotic Stress. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/39052 (accessed on 04 March 2026).

Swaminathan S, Lionetti V, Zabotina OA. CW Integrity Systems Involved in Plant Biotic Stress. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/39052. Accessed March 04, 2026.

Swaminathan, Sivakumar, Vincenzo Lionetti, Olga A. Zabotina. "CW Integrity Systems Involved in Plant Biotic Stress" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/39052 (accessed March 04, 2026).

Swaminathan, S., Lionetti, V., & Zabotina, O.A. (2022, December 21). CW Integrity Systems Involved in Plant Biotic Stress. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/39052

Swaminathan, Sivakumar, et al. "CW Integrity Systems Involved in Plant Biotic Stress." Encyclopedia. Web. 21 December, 2022.

Copy Citation

A cell wall (CW) has an established role in maintaining and determining cell shape, resisting internal turgor pressure, directing cell and plant growth, contributing to plant morphology, and regulating diffusion through the apoplast. Plants continually face environmental and biotic stresses, and these stressful conditions force the plants to evolve and develop monitoring systems to deal with the harsh conditions. The CW is a dynamic structure and the main site harboring different plant monitoring systems for perception and signaling plant immunity. Targeted genetic modifications of CW could be used as a tool to study the intricacy of defense priming and plant immunity.

plant cell wall

polysaccharides

cell wall integrity (CWI)

cell-wall-modifying enzymes (CWMEs)

cell-wall-digesting enzymes (CWDEs)

damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs)

surveillance

signaling cascade

pattern trig-gered immunity

1. Plant Cell Wall Components

Plant cell walls (CWs) show highly heterogeneous structures across different species, tissues, and developmental stages. Plant CWs are complex and dynamic biological networks composed of interacting polysaccharides, proteins, phenolic compounds, minerals, and water. CWs provide support and protection to plants, determine their morphology, and mediate cell adhesion and cell-to-cell communication during growth and development [1].

The CW polysaccharides range from linear to highly branched polymers. Cellulose, the main component of all types of CWs, possesses high tensile strength. It is composed of multiple hydrogen-bonded β-1,4-linked glucan chains to form cable-like microfibrils [2]. Hemicelluloses comprise different classes of polysaccharides (xyloglucans, xylans, and mannans) with sugar backbones linked by equatorial β-1,4 linkages, some of which are decorated with side chains [3]. Xyloglucan, the most abundant hemicellulose in type I primary walls, inherits a β-1,4-linked glucan backbone decorated with side chains consisting of xylose, galactose, and fucose residues. Xylans are the predominant hemicellulose in type II primary walls and eudicot secondary walls but are also present in small amounts in type I primary walls. Xylans have β-1,4-linked xylosyl backbones with side chains consisting of arabinose and glucuronic acid, some of which are methylated or feruloylated. Mannans, prevalent in gymnosperms and also present in other plant taxa, are polymers of β-1,4-linked mannose. Glucomannans consist of repeating disaccharide subunits of glucose and mannose joined by β-1,4 linkages. Mixed-linkage glucans (MLGs), common in rapidly growing grass tissues, contain β-1,4-linked stretches of glucose interspersed with β-1,3 linkages [3].

Pectins (homogalacturonan, xylogalacturonan, rhamnogalacturonan I, and rhamnogalacturonan II) are acidic polysaccharides enriched in galacturonic acid residues. Homogalacturonan (HG), the most abundant pectin, consists of continuous α-1,4-linked galacturonic acid residues that can be methylesterified at the C6 carboxyl groups and acetylated at O2 and O3 positions [4]. The backbone of rhamnogalacturonan I (RG I) consists of alternating galacturonic acid and rhamnose residues decorated with arabinan, galactan, and arabinogalactan side chains. Rhamnogalacturonan II (RG II), a highly conserved and complex pectin, consists of HG backbone decorated with side chains containing 13 different sugar subunits and over 20 distinct glycosyl linkages. Hemicelluloses and pectins are matrix polysaccharides. The nature of the structural diversity of pectin is due to its complex biosynthetic process, which requires a minimum of 67 different transferases, including glycosyltransferases, methyltransferases, and acetyltransferases [5][6].

Enzymes and nonenzymatic proteins are also present in CWs. Enzymes, including glycosyl-hydrolases, oxidoreductases, lyases, and esterases, are mainly involved in CW remodeling during different growth and defense processes. Structural proteins present in the CW include extensins, proline-rich proteins, and arabinogalactan proteins [1]. Lignin, abundant in secondary walls, is a hydrophobic, polyphenolic compound made of covalently linked monolignol subunits that undergo redox-mediated polymerization. Lignin can be covalently linked to the ferulate side chains of xylans [7].

2. Overview of CW Integrity Systems Involved in Plant Biotic Stress

A CW has an established role in maintaining and determining cell shape, resisting internal turgor pressure, directing cell and plant growth, contributing to plant morphology, and regulating diffusion through the apoplast. Plants continually face environmental and biotic stresses, and these stressful conditions force the plants to evolve and develop monitoring systems to deal with the harsh conditions [8][9][10]. Although previously considered only as a passive barrier against pathogens, it is now clear that the CW is a dynamic structure and the main site harboring different plant monitoring systems for perception and signaling plant immunity.

The molecular mechanisms underlying CW integrity (CWI) maintenance, aimed to monitor and fine tune a CW’s structural and functional integrity, are of particular interest. The mechanism involves various plasma membrane receptors and complex signal transduction pathways, which help the plant to maintain its growth through development as well as manage different adverse abiotic and biotic stresses [11][12][13]. ‘Plant-self’-derived damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) comprise plant molecules released in the apoplast. The DAMPs include wall-derived glycans and peptides, which, upon exposure of the plant to different stresses, are either de novo synthesized or processed to produce mature active ligands. Plants have a dedicated innate immunity system to monitor and maintain CWI, which comprises a diverse set of plasma-membrane-resident pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) to detect the DAMPs. Plants reinforce the perception system by using PRRs dedicated to detecting ‘non-self’-microbe-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs) or herbivore-associated molecular patterns (HAMPs) and activate pattern-triggered immunity (PTI). MAMPs are highly conserved microbial molecules derived from pathogens or parasites. The well-known MAMPs are flg22 from bacterial flagellin, chitooligomers from fungal CWs, and exoskeletons of insects [14]. The plant immune system can also recognize microbial effectors (Avr proteins) through cytoplasmic resistance (R) proteins, which results in triggering effector-triggered immunity (ETI) [15][16].

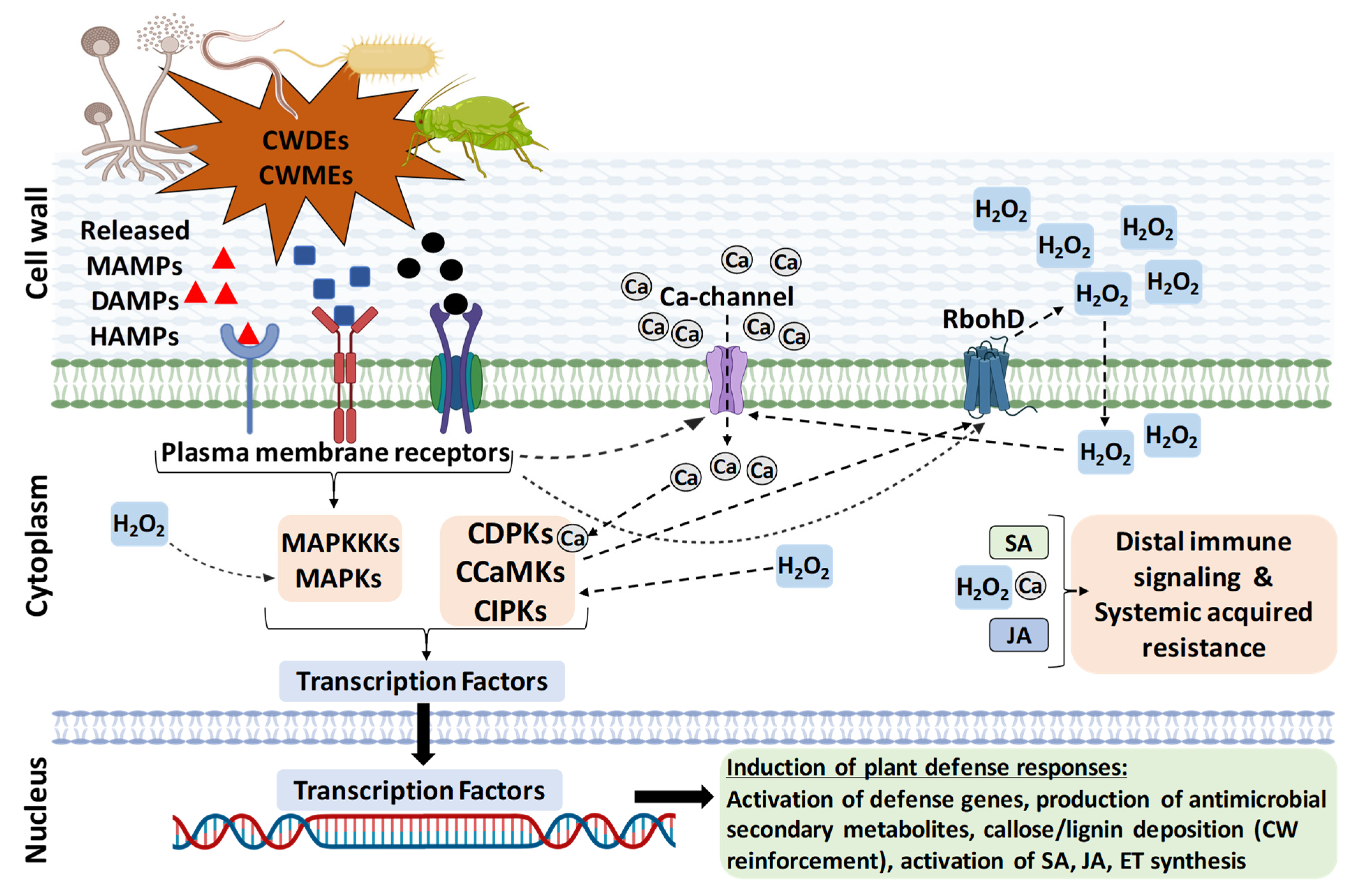

According to the “zig-zag model”, PTI is considered as the first line of defense activated by MAMPs through specific PRR [12]. ETI is the second layer of defense, triggered by the secreted microbial genotype-specific pathogenicity effectors and recognized by plant genotype-specific receptor proteins (R). The effects of PTI include rapid activation of a broad spectrum of defense responses, such as oxidative burst, Ca2+ influx, nitric oxide accumulation, protein kinases activation, and cell wall reinforcement (Figure 1). Transcriptional reprogramming leads to induction of defense-related genes to generate secondary metabolites/anti-microbial compounds, induction of enzymes to digest the microbial CW (chitinases, β-1-3 glucanases), and activation of the ethylene (ET), salicylic acid (SA), and jasmonic acid (JA) pathways, which are late outcomes of the PTI response [17][18] (Figure 1). ETI is characterized by a higher and longer response, which, in many cases, results in a localized programmed cell death known as a “hypersensitive response” [19]. PTI and ETI are inter-dependent and mutually enhance each other to provide total immunity to plants, which might share signaling components and responses produced by DAMPs [20][21][22]. Moreover, local activation of immunity confers wide-spectrum protection against pathogens in distal tissues, known as systemic acquired resistance (SAR), which mainly involves the hormone SA and JA [13].

Figure 1. An overview of plant defense pathway triggered by perturbation of cell wall integrity during biotic stresses. The DAMPs, MAMPs, or HAMPs elicitors released due to biotic stresses are sensed through the plasma-membrane-localized pattern-recognition receptors (PRR) that activate the host defense pathway. The elicitor binding to PRRs activates a series of events, such as activation of Ca-channels and Ca influx, activation of reactive oxygen species production (ROS burst; H2O2), and protein kinases (MAPKs) cascade activation, and these are inter-linked with each other. The MAPK and Ca-dependent kinase (CDPKs, CCaMKs, and CIPKs) cascades further activate transcriptional reprogramming, defense-related PTI genes, reinforcement of cell wall (callose and lignin deposition), generation of anti-microbial secondary metabolites, and activation of ET, SA, and JA hormone synthesis. Locally activated immunity is amplified through these hormones. Immunity may also involve the spread of defense responses to distal tissues, resulting in systemic acquired resistance (SAR). It should be emphasized that a general view of only the pattern triggered immunity is described here and that each pathosystem may involve specific molecular interactions.

Research findings extensively demonstrated that alterations in CWI can be achieved either by intentional chemical perturbation, overexpression (OE), or mutation of CW-related genes/enzymes. As a result, the triggered signaling pathways can significantly impact disease resistance and/or abiotic stresses. CW danger signaling can also be stimulated by expressing microbial CW-degrading enzymes (CWDEs) in planta. Fungi produce a notable quantity and variety of CWDEs, mostly belonging to glycosyl hydrolases [23]. Soft rot bacteria also synthesize significant CWDEs that contribute to their virulence [24]. Several parasitic nematodes and phytophagous insects also produce CWDEs for their invasion [25][26][27]. Moreover, parasitic plants produce a haustorium highly expressing CWDEs [28]. A specific CWDE is used to achieve desired modification in the CW components and is a highly valuable tool to understand the physiological consequences arising from that particular modification [29].

It was initially thought that the disease resistance phenotypes observed with alterations in CWI were due to the inability of mis-adapted pathogens to overcome the genetically modified wall compositions/structures in the genetically modified plants [11]. However, later studies found that a CW is a highly dynamic component of a cell and not just a passive barrier. CW alterations and DAMPs trigger complex defensive signaling immune pathways to fight against plant pathogens, inducing defense responses and reinforcement of the CW [11]. Recent research with a large set of Arabidopsis CW mutants revealed that CWs of mutant plants exhibited high diversity of composition alterations, as revealed by glycome profiling [30]. Moreover, it reported that plant CWs are determinants of immune responses and illustrated the relevance of CW composition in determining disease-resistance phenotypes to pathogens with different parasitic styles.

CWI alterations, in some instances, can provide tolerance/resistance to pathogens, while, in other cases, they result in susceptibility. Therefore, expression of endogenous CW-modifying enzymes (CWMEs) or microbial CWDEs and their inhibitors in planta is a highly useful tool mainly to investigate the molecular mechanisms behind CWI maintenance during stress, unearth plant immunity and complex signaling pathways, and host plant–microbe interactions. Further, it is also useful in improving crop protection against plant pathogens [29][31][32][33][34][35].

The artificial CW modifications could induce plant defense immunity reactions constitutively even prior to pathogen attack, and these defenses may be able to help the plants to resist the pathogen during actual attack [35][36]. Several efforts were made to unravel the complexity behind the CW role in plant pathogen resistance. Indeed, increasing evidence demonstrates that changes in CW composition, either via altering polysaccharides biosynthesis or post-synthetic modifications of polysaccharides in muro, can induce reactions similar to those induced during plant responses to stresses. Their research findings also indicated that studies on CW modifications and defense priming are highly complicated and not yet fully elucidated in many cases. There is much to investigate to completely understand the complex molecular nature of the host plant–pathogen interaction and CW mediated defense priming and plant immunity [11][37].

References

- Anderson, C.T.; Kieber, J.J. Dynamic construction, perception, and remodeling of plant cell walls. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2020, 71, 39–69.

- Zhang, T.; Zheng, Y.Z.; Cosgrove, D.J. Spatial organization of cellulose microfibrils and matrix polysaccharides in primary plant cell walls as imaged by multichannel atomic force microscopy. Plant J. 2016, 85, 179–192.

- Scheller, H.V.; Ulvskov, P. Hemicelluloses. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2010, 61, 263–289.

- Atmodjo, M.A.; Hao, Z.; Mohnen, D. Evolving views of pectin biosynthesis. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2013, 64, 747–779.

- Anderson, C.T. We be jammin’: An update on pectin biosynthesis, trafficking and dynamics. J. Exp. Bot. 2016, 67, 495–502.

- Mohnen, D. Pectin structure and biosynthesis. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2008, 11, 266–277.

- Vanholme, R.; Demedts, B.; Morreel, K.; Ralph, J.; Boerjan, W. Lignin biosynthesis and structure. Plant Physiol. 2010, 153, 895–905.

- Panstruga, R.; Parker, J.E.; Schulze-Lefert, P. SnapShot: Plant immune response pathways. Cell 2009, 136, 978.e1–978.e3.

- Hofte, H.; Voxeur, A. Plant cell walls. Curr. Biol. 2017, 27, R865–R870.

- Engelsdorf, T.; Hamann, T. An update on receptor-like kinase involvement in the maintenance of plant cell wall integrity. Ann. Bot. 2014, 114, 1339–1347.

- Bacete, L.; Melida, H.; Miedes, E.; Molina, A. Plant cell wall-mediated immunity: Cell wall changes trigger disease resistance responses. Plant J. 2018, 93, 614–636.

- Jones, J.D.G.; Dangl, J.L. The plant immune system. Nature 2006, 444, 323–329.

- Li, P.; Lu, Y.J.; Chen, H.; Day, B. The lifecycle of the plant immune system. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2020, 39, 72–100.

- Choi, H.W.; Klessig, D.F. DAMPs, MAMPs, and NAMPs in plant innate immunity. BMC Plant Biol. 2016, 16, 232.

- Boutrot, F.; Zipfel, C. Function, discovery, and exploitation of plant pattern recognition receptors for broad-spectrum disease resistance. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2017, 55, 257–286.

- Tanaka, K.; Heil, M. Damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) in plant innate immunity: Applying the danger model and evolutionary perspectives. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2021, 59, 53–75.

- Bigeard, J.; Colcombet, J.; Hirt, H. Signaling mechanisms in pattern-triggered immunity (PTI). Mol. Plant 2015, 8, 521–539.

- Peng, Y.J.; van Wersch, R.; Zhang, Y.L. Convergent and divergent signaling in PAMP-triggered immunity and effector-triggered immunity. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2018, 31, 403–409.

- Cui, H.; Tsuda, K.; Parker, J.E. Effector-triggered immunity: From pathogen perception to robust defense. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2015, 66, 487–511.

- Ngou, B.P.M.; Ahn, H.K.; Ding, P.; Jones, J.D.G. Mutual potentiation of plant immunity by cell-surface and intracellular receptors. Nature 2021, 592, 110–115.

- Pruitt, R.N.; Locci, F.; Wanke, F.; Zhang, L.; Saile, S.C.; Joe, A.; Karelina, D.; Hua, C.; Froehlich, K.; Wan, W.L.; et al. The EDS1-PAD4-ADR1 node mediates Arabidopsis pattern-triggered immunity. Nature 2021, 598, 495–499.

- Tian, H.; Wu, Z.; Chen, S.; Ao, K.; Huang, W.; Yaghmaiean, H.; Sun, T.; Xu, F.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; et al. Activation of TIR signalling boosts pattern-triggered immunity. Nature 2021, 598, 500–503.

- Kubicek, C.P.; Starr, T.; Glass, N.L. Plant cell wall-degrading enzymes and their secretion in plant-pathogenic fungi. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2014, 52, 427–451.

- Charkowski, A.; Blanco, C.; Condemine, G.; Expert, D.; Franza, T.; Hayes, C.; Hugouvieux-Cotte-Pattat, N.; Lopez Solanilla, E.; Low, D.; Moleleki, L.; et al. The role of secretion systems and small molecules in soft-rot enterobacteriaceae pathogenicity. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2012, 50, 425–449.

- Mostafa, S.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, W.; Jin, B. Plant responses to herbivory, wounding, and infection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7031.

- Snoeck, S.; Guayazán-Palacios, N.; Steinbrenner, A.D. Molecular tug-of-war: Plant immune recognition of herbivory. Plant Cell 2022, 34, 1497–1513.

- Erb, M.; Reymond, P. Molecular interactions between plants and insect herbivores. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2019, 70, 527–557.

- Mitsumasu, K.; Seto, Y.; Yoshida, S. Apoplastic interactions between plants and plant root intruders. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 617.

- Pogorelko, G.; Lionetti, V.; Bellincampi, D.; Zabotina, O.A. Cell wall integrity targeted post-synthetic modifications to reveal its role in plant growth and defense against pathogens. Plant Signal. Behav. 2013, 8, e25435.

- Molina, A.; Miedes, E.; Bacete, L.; Rodríguez, T.; Mélida, H.; Denancé, N.; Sánchez-Vallet, A.; Rivière, M.P.; López, G.; Freydier, A.; et al. Arabidopsis cell wall composition determines disease resistance specificity and fitness. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2010243118.

- Lionetti, V.; Cervone, F.; Bellincampi, D. Methyl esterification of pectin plays a role during plant-pathogen interactions and affects plant resistance to diseases. J. Plant Physiol. 2012, 169, 1623–1630.

- Lionetti, V.; Fabri, E.; De Caroli, M.; Hansen, A.R.; Willats, W.G.T.; Piro, G.; Bellincampi, D. Three pectin methylesterase inhibitors protect cell wall integrity for Arabidopsis immunity to Botrytis. Plant Physiol. 2017, 173, 1844–1863.

- Lionetti, V.; Raiola, A.; Camardella, L.; Giovane, A.; Obel, N.; Pauly, M.; Favaron, F.; Cervone, F.; Bellincampi, D. Overexpression of pectin methylesterase inhibitors in Arabidopsis restricts fungal infection by Botrytis cinerea. Plant Physiol. 2007, 143, 1871–1880.

- Pogorelko, G.; Fursova, O.; Lin, M.; Pyle, E.; Jass, J.; Zabotina, O.A. Post-synthetic modification of plant cell walls by expression of microbial hydrolases in the apoplast. Plant Mol. Biol. 2011, 77, 433–445.

- Swaminathan, S.; Reem, N.T.; Lionetti, V.; Zabotina, O.A. Coexpression of fungal cell wall-modifying enzymes reveals their additive impact on Arabidopsis resistance to the fungal pathogen, Botrytis cinerea. Biology 2021, 10, 1070.

- Pogorelko, G.; Lionetti, V.; Fursova, O.; Sundaram, R.M.; Qi, M.; Whitham, S.A.; Bogdanove, A.J.; Bellincampi, D.; Zabotina, O.A. Arabidopsis and Brachypodium distachyon transgenic plants expressing Aspergillus nidulans acetylesterases have decreased degree of polysaccharide acetylation and increased resistance to pathogens. Plant Physiol. 2013, 162, 9–23.

- Narváez-Barragán, D.A.; Tovar-Herrera, O.E.; Guevara-García, A.; Serrano, M.; Martinez-Anaya, C. Mechanisms of plant cell wall surveillance in response to pathogens, cell wall-derived ligands and the effect of expansins to infection resistance or susceptibility. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 969343.

More

Information

Subjects:

Plant Sciences

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.1K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

22 Dec 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No