Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dmitry S. Sitnikov | -- | 3796 | 2022-12-20 09:32:02 | | | |

| 2 | Dean Liu | -1 word(s) | 3795 | 2022-12-21 02:38:26 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Ilina, I.V.; Sitnikov, D.S. Nonlinear Microscopy in Developmental Biology: Ultrashort Lasers Application. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/38987 (accessed on 08 February 2026).

Ilina IV, Sitnikov DS. Nonlinear Microscopy in Developmental Biology: Ultrashort Lasers Application. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/38987. Accessed February 08, 2026.

Ilina, Inna V., Dmitry S. Sitnikov. "Nonlinear Microscopy in Developmental Biology: Ultrashort Lasers Application" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/38987 (accessed February 08, 2026).

Ilina, I.V., & Sitnikov, D.S. (2022, December 20). Nonlinear Microscopy in Developmental Biology: Ultrashort Lasers Application. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/38987

Ilina, Inna V. and Dmitry S. Sitnikov. "Nonlinear Microscopy in Developmental Biology: Ultrashort Lasers Application." Encyclopedia. Web. 20 December, 2022.

Copy Citation

The evolution of laser technologies and the invention of ultrashort laser pulses have resulted in a sharp jump in laser applications in life sciences. Developmental biology is no exception. The unique ability of ultrashort laser pulses to deposit energy into a microscopic volume in the bulk of transparent material without disrupting the surrounding tissues makes ultrashort lasers a versatile tool for precise microsurgery of cells and subcellular components within structurally complex and fragile specimens like embryos as well as for high-resolution imaging of embryonic processes and developmental mechanisms.

ultrashort laser pulses

femtosecond laser

developmental biology

embryo development

1. Introduction

Lasers have become a powerful tool in basic biological research and medicine [1]. A massive variety of laser applications exists in ophthalmology [2], dermatology [3], and surgery [4][5]. The most fascinating and promising implementations of laser technology are based on the ability of laser light to perform precise micromanipulations (microdissections) at the cellular and even subcellular levels. Recently, some valuable laser-based devices and technologies have been developed. For example, laser-assisted microdissection and pressure catapulting by the PALM Microbeam system (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) allow fast and noncontact isolation of the desired cell segment from the undesired one [6][7]. The technology is widely applied in the molecular analysis of cancer specimens, enabling it to overcome one of the major challenges related to tissue heterogeneity. Laser-based technologies are also promising approaches in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. The technology of laser guidance direct writing proposed by Odde and Renn [8] in 1999 utilized laser-induced optical forces to guide and deposit particles of various sizes onto solid surfaces. Many developments and novel techniques of laser-assisted bioprinting have been proposed [9] since then, making possible the construction of various tissues or organs such as vessels, heart, and liver [10].

Berns et al. [11] in 1981 and others [12][13] have repeatedly highlighted the benefits of using lasers in cell and developmental biology. As laser technology has made great progress over the past 40 years, the range of possible applications of lasers in developmental biology has also substantially increased.

A key achievement in laser physics is the invention of ultrashort lasers. The physicists Gérard Mourou and Donna Strickland, the winners of the 2018 Nobel prize, made a breakthrough in high-intensity, ultra-short optical pulse generation with their chirped-pulse amplification technique. Ultrashort laser pulse (ULP) commonly implies a pulse with duration in the pico- (1 ps = 10−12 s) or femtosecond range (10 fs = 10−14 s) and high peak intensity. Shorter pulse durations are hard to obtain and implement due to light dispersion in the matter it passes through along its way from the laser to the sample, which has to be taken into account and compensated. Laser pulses with durations shorter than 80–100 fs are commonly not applied. Due to high intensity of laser pulses new mechanisms of laser-matter interaction take place. Nonlinear optical effects in the focal volume of tightly focused ULP offer several advantages compared to long-pulsed (nano- and microsecond) or continuous wave (CW) lasers. The absence of adverse effects like out-of-focus light absorption or substantive heat transfer from the focal point to the surrounding media facilitates high precision microsurgery of cells and tissue with minimal collateral damage. Using ULPs has also created new possibilities for imaging cells and tissues, as nonlinear optical microscopy offers several advantages over conventional microscopies, like high resolution and non-invasiveness without needing exogenous markers.

2. Interaction of Ultrashort Laser Pulses with Matter

Let's consider the peculiarities of ULPs interaction with matter to see all the advantages provided. The nonlinear absorption process, a distinguishing feature of ULP, is briefly described below. Water is commonly used as a basis for modeling processes during ULPs-tissue interaction because water has similar properties to biological media in absorptance, optical breakdown threshold, and thermal properties [14][15]. Since 1991, water has been considered an “amorphous semiconductor” [16] with a band gap (BG) of 6.5 eV separating the valence band (VB) and the conduction band (CB). The complex energy structure of water is thoroughly studied; modern concepts can be found elsewhere [17][18].

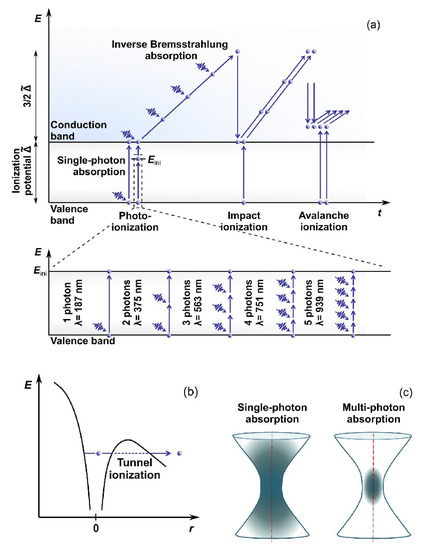

Electrons are the key players in the absorption process of photons of the laser pulse. The acquired energy results in electron transition from the VB to the CB. However, water’s bandgap energy is higher than a photon’s energy in the visible or near-infrared (NIR) light region. Being focused, ULPs are characterized by high intensity, i.e., high concentration of photons, making photoionization possible (Figure 1). The photoionization can typically occur through two processes called multiphoton absorption [19] or tunneling ionization [20]. Each process’s probability depends on the field strength and frequency of the electromagnetic field. These first free electrons in the CB during collisions with ions or atomic nuclei facilitate the process of further photon absorption from the incoming radiation (the so-called inverse Bremsstrahlung absorption). The electrons accumulate the kinetic energy, help transfer the remaining electrons from the VB to the CB through impact and avalanche ionization (see, e.g., Ref. [21] for details), and form the so-called low-density plasma in the laser beam focus area.

Figure 1. Water ionization scheme for laser energy deposition: (a) multiphoton, avalanche and impact ionization, (b) tunnel ionization, and (c) Single- and multiphoton absorption geometry. Adapted from open-access (CC BY license) source, Ref. [22].

The interaction between laser radiation and water or biological tissue is a complex process where particular laser-induced effects depend on several values and parameters like laser power (intensity or pulse energy), wavelength, pulse duration, repetition rate, and characteristic properties of the tissue to be laser-processed.

Formation of electron plasma in laser focus results in temperature increase. A detailed description of absorption processes and temperature estimation can be found in a series of studies by Vogel et al. [23][24]. The authors also demonstrated [25] that a temperature of 100 °C can easily be reached in laser focus (wavelength λ = 800 nm, pulse duration τ = 170 fs, and repetition rate = 80 MHz) at intensity = 3.3 × 1012 W cm−2 causing photothermal effect of denaturation of biomolecules. This effect is also accompanied by free-electron-induced chemical effects due to the high reactivity of the electrons.

The chemical effects in biological media are commonly divided into two groups: (1) Changes in the water molecules create reactive oxygen species (ROS), subsequently affecting organic molecules. OH* and H2O2 oxygen species have been shown to cause cell damage [26]; the process of their formation following the ionization and dissociation of water molecules is described in detail [27]. (2) Direct changes of the organic molecules are about the capture of electrons into an antibonding molecular orbital, initiating the biomolecules’ fragmentation [23][26][28]. For multiple pulses, this accumulative effect can lead to dissociation/dissection of biological structures exposed to low-density plasmas generated by femtosecond laser radiation (e.g., DNA strand breaks [28]). It has recently been shown that femtosecond laser pulses with relatively small peak intensity (λ = 794 nm, τ = 100 fs, and = 80 MHz, ≤ 4 × 1011 W cm−2) could act as a highly localized ionizing tool [29]. They can induce complex DNA damage involving different repair pathways. Thus, the local ionizing effect should be considered when femtosecond laser radiation is used for biomedical applications.

Another type of effect induced by ULPs is the tensile stress in the medium. Local temperature increase results in thermal expansion. Because energy delivery by ULP is faster than the medium can expand [30], substantial transient stresses are developed. In water, when the tensile strength of the liquid is exceeded, it causes the formation of a cavitation bubble. Thus, the tensile stress wave may induce object fracture even after a temperature rise is too small to produce thermal damage [31].

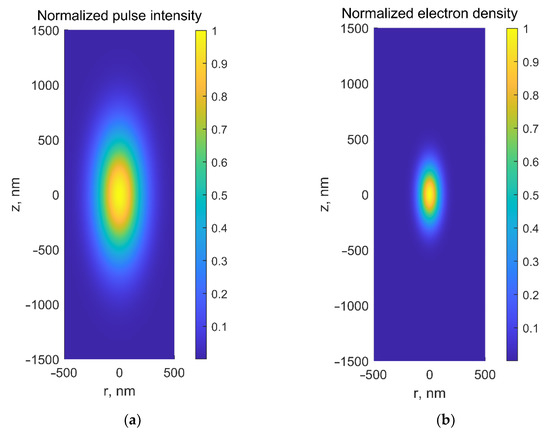

The multiphoton absorption process has several advantages, dealing with transparent materials not absorbing at low intensities at a given wavelength. Applying ULPs with high photon concentration increases the probability of multiphoton absorption at high intensities in laser focus. Thus, firstly, laser-matter interaction in a transparent medium occurs in a small volume only in the vicinity of the beam waist (Figure 1c), thus enabling selective laser-based microsurgery of cells or subcellular structures (e.g., embryo cells or intracellular organelles) without disrupting surrounding tissues or cell membranes. Secondly, nonlinear absorption prevents the medium from heating along the laser beam path. Furthermore, the spatial distribution of the free electrons in focal volume is narrower than intensity distribution by a factor of , where is the number of photons captured simultaneously by the electron (Figure 2). Thus, low-density plasma’s heating, thermomechanical, and chemical effects produced are very well localized in a small volume, making possible microsurgery with subdiffraction spatial resolution. Moreover, laser surgery with ultrashort lasers can be conducted with much less average power than long-pulsed or CW lasers. Application of the latter for surgery usually requires staining target structures (to create additional energy levels within the BG) unless laser powers higher than 1 W are used. The average power required for femtosecond laser-based microsurgery was substantively lower (cf. Cell microsurgery utilizing CW argon laser at wavelengths λ = 488 nm/514 nm required laser power of 1 W [32], while an average power of 30 mW [33][34] was enough to perform microsurgery with femtosecond Ti:sapphire laser at a wavelength λ = 800 nm).

Figure 2. (a) Normalized laser intensity and (b) normalized electron-density distributions in the focal area at λ = 800 nm for NA = 1.3.

When considering ULPs, two types of femtosecond lasers should be mentioned, with repetition rates in the MHz and kHz frequency ranges. The former source comprises typical seed oscillators, generating pulse trains with small energies of tens of nanojoules and periods of about 10 ns. The latter source is additionally equipped with a regenerative amplifier, enabling an increase of pulse energy up to the millijoule level for the reduced pulse repetition rate. Thus, two different microsurgery scenarios should be considered. Due to low pulse energy, accumulative chemical effects in a low-density plasma regime justify microsurgery in case of MHz pulse repetition rate, while laser microdissection at kHz repetition rate mainly relies on thermoelastically induced formation of transient cavities.

3. Application of Ultrashort Laser Pulses for Nonlinear Microscopy of Embryos

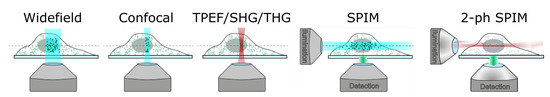

Traditional single-photon fluorescence (SPF) microscopy covers the radiation of light-emitting probes (fluorescent proteins, dye molecules, and semiconductor nanoparticles) chemically associated with specific biological elements (proteins, DNA, and phospholipids). Probes’ spatial distribution is recorded in widefield or point scanning mode with subsequent image reconstruction (Figure 3). Additional equipment like high numerical aperture lenses and pinholes is required to achieve spatial filtering and remove out-of-focus light or glare. Studying the dynamics of embryonic development using SPF can be impeded as cell exposure to visible [35][36][37] or high-intensity light [38] can cause oocyte or embryo damage. Moreover, using classic SPF microscopy is difficult as a need exists to monitor embryo development for a comparatively long period (from several hours to several days). This fact highlights the importance of improving long-term fluorescence imaging techniques.

Figure 3. Principal schemes for microscopy modalities. Adapted from an open-access (CC BY license) source; Ref. [39].

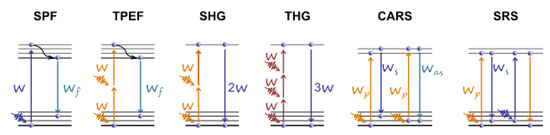

The development of nonlinear optical (NLO) microscopy overcomes most previous limitations, enabling effective imaging at greater depths with higher spatial resolution without staining. The most suitable for biological research NLO-microscopy modalities include two-photon excited fluorescence (TPEF) [40], generation of the second and third harmonics (SHG and THG) [41][42], and coherent Raman scattering (CRS) microscopy [43].

Application of ULPs in NLO microscopy revealed some features related to pulse transportation from laser to the sample. While passing though microscope optics, the low frequencies of broadband pulse spectrum travel faster than high frequencies due to group velocity dispersion effect. Thus, original short pulse becomes longer and demonstrates time dependence of its instantaneous frequency (chirp phenomenon). This results in decrease in pulse intensity, a key parameter for multiphoton absorption. To deliver laser pulse with duration of several tens of femtoseconds to the sample a special tunable-chirp laser systems have to be applied. They allow to generate a “negative-chirp” pulse (at laser output), high frequencies of which travel in the front of the pulse. The value of this negative dispersion is chosen to be compensated by positive dispersion in microscope optics.

Two-photon fluorescence microscopy, also known as two-photon laser scanning (TPLS) microscopy, is based on the simultaneous absorption of two photons. This modality allows for the visualization of both exogenous and endogenous fluorophores [44]. Because TPEF is based on the nonlinear phenomenon, it offers a higher penetration depth of illumination, higher spatial resolution, and actual 3D scanning capability. Unfortunately, photobleaching and photodamage may occur at the focal volume where photochemical interactions occur.

The SHG is a second-order nonlinear process, in which two photons interacting with a nonlinear material are upconverted to form a new photon with twice the frequency of initial photons. The medium should be noncentrosymmetric to obtain the SHG signal. It is generated in collagen and astroglial fibers, myofilaments, and polarized tubulin assemblies like mitotic spindles. The SHG process originates from induced polarization instead of actual absorption, resulting in a substantial decrease in the probability of phototoxicity and photobleaching. SHG microscopy is considered relatively non-invasive, since there is no need in adding exogenous markers. Besides, there is no energy contribution to the biological object, since the energy of a pair of excitation photons and that of the SHG photon are equal.

In contrast to SHG, THG microscopy does not require asymmetry of molecules to generate the signal. The third-harmonic waves generated before and after the laser focal point interfere destructively, resulting in zero net THG [45] if the medium around the focal point is homogeneous. In inhomogeneity, like an interface between two media and a mismatch of refractive indices [46][47], the symmetry along the optical axis is broken, and the third harmonic wave can be detected. In cells, THG signals are commonly detected from mitochondria and lipid bodies. Higher harmonic-generation microscopy, including SHG and THG, leaves no energy deposition to the interacted matters providing a truly non-invasive modality. Details on these techniques, seeming ideal for in vivo imaging of live specimens without any preparation, can be found elsewhere [48].

Raman scattering is a molecule/material identification technique based on the characteristic vibrational spectrum. In CRS microscopy, the Raman signal is generated from a coherent superposition of the molecules in the sample. The sample is irradiated by two synchronized ULPs of different frequencies, the pump , and the Stokes . When their difference, , matches the vibrational frequency, resonant excitation and in-phase vibration of all the molecules in the focal volume are observed. Two most widely applied CRS techniques are the stimulated Raman scattering (SRS) [49] and the coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering (CARS) [50] (see the diagrams for the aforementioned microscopy modalities in Figure 4). Parodi et al. have compared and described these techniques in detail [44]. Wang et al. present recent advances in the development of label-free optical imaging techniques for application in developmental biology [51].

Figure 4. Energy level diagrams for various microscopy modalities (from left to right) for single-photon (SPF) and two-photon excited (TPEF) fluorescence, second (SHG) and third (THG) harmonic generation, coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering (CARS), and stimulated Raman scattering (SRS). Adapted from an open-access (CC BY license) source; Ref. [22].

Another microscopy modality that should be mentioned is light-sheet microscopy, a century-old known as selective-plane illumination microscopy (SPIM). The sample is illuminated with a plane of visible light, generating fluorescence from a thin optical section, which is then imaged with a widefield camera orthogonally to the light sheet. The orthogonal geometry between the illumination and detection pathways, enables higher imaging speed owing to the parallel image collection and reduces photodamage because only a single focal plane of the sample is illuminated at a time [52]. This microscopy modality has been upgraded in several studies [52][53] by applying ULPs combined with TPLS. Such a scheme, called 2-ph SPIM, combines the advantages of both modalities. TPLS provides high penetration length in scattering tissues, while conventional SPIM (or 1-ph SPIM) offers higher acquisition speed. Near-infrared ULPs are used to create a two-photon excitation light sheet, which performs axial sectioning. The 2-ph SPIM also offers better axial resolution than 1-ph SPIM at large sample depth. Firstly, scattering of excitation light is reduced at near-infrared (compared to visible) wavelengths, providing better preservation of the light-sheet thickness. Secondly, quadratic dependence on the excitation light intensity of two-photon–excited fluorescence makes scattered illumination light less important, as fluorophore excitation is spatially confined to only the highest intensity part of the beam, thus preserving axial resolution even when the light sheet is thickened by scattering [52]. Bidirectional illumination can be applied to increase the useful field of view of camera.

Many studies have been published over the last decades reporting on applying nonlinear microscopy in developmental biology.

Drosophila melanogaster and zebrafish (Danio rerio) are popular model organisms. The former is considered to be a powerful platform for understanding the interplay between genetics and biophysics (see the review [54] and references therein) and for reverse-engineering multicellular systems. Drosophila and zebrafish require minimal preparations and maintenance for live imaging. In contrast, mammalian models, such as mice, require optimal embryo culture for live imaging [55]. The mouse is the only mammalian organism with well-established genetic engineering strategies to generate various disease model. The efficient development and use of these mutant mice necessitate phenotypic imaging analyses of the created models, accentuating the importance developing efficient approaches for high-resolution mouse embryonic imaging [51]. A recent review discusses studies employing TPEF, SHG, THG, or CRS microscopy techniques for mouse embryo quality assessment and strategies for embryo selection with high implantation potential [22]. Moreover, SHG microscopy can be a valuable imaging tool for exploring mouse embryonic cardiogenesis and biomechanics [56]. SHG combined with TPEF microscopy of genetic mouse model enabled visualization of establishing cardiac fibers and resulted in detection of a substantial increase in fibrillar content and organization during the first 24 h after initiation of contractions.

Zebrafish is an excellent animal model for in vivo studies due to its transparency during embryogenesis, its amenability to optical imaging, and the easiness of transgenic line generations [57]. Zebrafish embryos are also ideal model vertebrates for high-throughput toxicity [58]. Detailed study of live zebrafish embryos and larvae using non-invasive TPEF, SHG, and Light-Sheet microscopy techniques can be found in a recent review (see Ref. [57] and references therein). The review [57] covers the pros and cons of the listed modalities and their application to study, for example, the dynamics of cytological construction, development of cranial neurons and blood vessels during embryogenesis, and organization of collagen fibers during the fin wound healing.

Higher-harmonic generation techniques (SHG and THG) have a solid potential for long-term in vivo study of the nervous system, including genetic disorders, axon pathfinding, neural regeneration, neural repair, and neural stem cell development [59]. By utilizing endogenous SHG as the contrast of polarized nerve fibers and THG to reveal morphological changes, the vertebrate embryonic nervous development was successfully observed in a live zebrafish embryo from the very beginning using a near-infrared light source (Cr: forsterite laser, = 110 MHz, λ = 1230 nm, τ = 140 fs, and = 100 mW) [59]. Generation of SHG from myelinated nerve fibers and the outer segment of the photoreceptors with a stacked membrane structure were also reported for the first time.

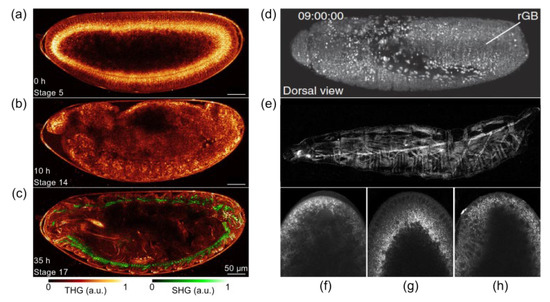

SHG microscopy has also been used to explore the trachea system, developing muscle structures in 2nd-instar larva, and the lipid bodies in Drosophila cells [60][61] to investigate the structure of Drosophila sarcomeres and to visualize myocyte activity in terms of rhythmic muscle contraction of both larval and adult stages [62][63]. In a later study [64], a question of laser-induced toxicity of THG imaging has been raised. The influence of imaging rate, wavelength, and pulse duration on the short-term and long-term perturbation of Drosophila embryos development has been studied and the criteria for safe imaging have been defined. Conducted studies enabled authors to derive general guidelines for improving the signal-to-damage ratio in two-photon (TPEF/SHG) or THG imaging (see examples in Figure 5). Imaging of lipid droplets that exhibit highly dynamic behavior in early Drosophila embryo provides a robust platform for the investigation of shuttling by kinesin and dynein motors. Real-time imaging and quantification of droplet motion using an efficient and convenient technique termed ‘‘femtosecond-stimulated Raman loss’’ microscopy (Figure 5f–h) enabled Dou et al. [65] to develop a velocity-jump model to predict the population distributions of droplet density.

Figure 5. (a–c) Long-term THG-SHG imaging of Drosophila embryonic development. 2D THG-SHG imaging at a wavelength of 1180 nm of a wild-type Drosophila embryo during 36 h starting from stage 5 up to the larvae stage (i.e., until hatching). Reprinted from an open-access (CC BY license) Ref. [64]. (d) Combination of TPEF with SPIM that delivers high imaging speeds and near complete physical coverage of the embryo while reducing photobleaching and phototoxic effects. (e) SHG microscopy visualizes muscular architecture and trachea system in detail without fluorophore labeling. Adapted from an open-access (CC BY license) Ref. [54]. (f–h) fSRL (i.e., femtosecond stimulated Raman loss) images of lipid droplet global distribution during Drosophila early embryogenesis at phases of nuclear cycle 13, midcellularization, and gastrulation, respectively. Adapted from an open-archive source (Ref. [65]).

Recent technological advances have facilitated whole-brain recording in small organisms, including Drosophila melanogaster, nematode Caenorhabditis elegans, and zebrafish Danio rerio [66]. Drosophila melanogaster is a popular model for brain studies due to a small number of neurons interacting in limited circuits, allowing analysis of individual computations or steps of neural processing. Light sheet fluorescence microscopy also allows automated imaging of Drosophila melanogaster embryos [67]. Memeo et al. have developed a new microscope on a chip comprising optical and fluidic components (for embryo alignment) [67]. Two different Drosophila populations expressing GFP and mRFP have been successfully processed at two wavelengths (488 nm and 561 nm, correspondingly), and 3D observation of the internal organs, segmentation, and quantification of their volume has been demonstrated.

Applying THG microscopy makes it possible to detect altered photoreceptor development in Drosophila pupal eye that may be helpful in clinically relevant conditions associated with photoreceptor degeneration [68]. In their later study, Karunendiran et al. [69] successfully applied polarimetric SHG microscopy to characterize the changes in myosin accumulation in the Drosophila larva body wall muscles. Experiments revealed changes in somatic muscle striated patterns and reduced signal intensity correlated with diminished order of myosin filaments. Polarization-resolved SHG technique enabled extracting the nonlinear susceptibility tensor components ratio of myosin fibrils in the body wall muscles of Drosophila larva [70].

4. Conclusions

Advances in ultrashort laser sources have facilitated their application in life sciences, and developmental biology is no exception. Due to nonlinear mechanisms of absorption of ULPs, energy deposition occurs in a small diffraction-limited volume in the bulk of a transparent material, thus minimizing possible damage to surrounding tissues. Therefore, the steady and continuous growth of applications of femtosecond or picosecond lasers for precise microsurgery and modification of cells and subcellular structures within living embryos has existed. Successful microsurgery and ablation of preimplantation mammalian embryos and externally developing embryos have been demonstrated. Moreover, femtosecond lasers are a safe, reliable, and efficient tool for precise three-dimensional imaging of embryos. NLO microscopy with femtosecond laser pulses includes TPEF, generation of the second and third harmonics, and CRS microscopy and offers several advantages over conventional fluorescence microscopy. NLO microscopy techniques are widely used in developmental biology for high-precision visualization of embryos, evaluating their quality and developmental potential, and investigating embryo change post-femtosecond laser-based microsurgery. It should be mentioned that cell microsurgery and imaging can be performed by using the very same femtosecond laser system. A few representative examples of simultaneous application of femtosecond lasers for ablation and imaging can be found elsewhere [71].

References

- Litvinova, K.S.; Rafailov, I.E.; Dunaev, A.V.; Sokolovski, S.G.; Rafailov, E.U. Non-invasive biomedical research and diagnostics enabled by innovative compact lasers. Prog. Quantum Electron. 2017, 56, 1–14.

- Prasad, A. Laser Techniques in Ophthalmology: A Guide to YAG and Photothermal Laser Treatments in Clinic; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022; ISBN 1000538486.

- Gianfaldoni, S.; Tchernev, G.; Wollina, U.; Fioranelli, M.; Roccia, M.G.; Gianfaldoni, R.; Lotti, T. An Overview of Laser in Dermatology: The Past, the Present and … the Future (?). Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2017, 5, 526–530.

- Khalkhal, E.; Rezaei-Tavirani, M.; Zali, M.R.; Akbari, Z. The Evaluation of Laser Application in Surgery: A Review Article. J. Lasers Med. Sci. 2019, 10, S104–S111.

- Chung, S.H.; Mazur, E. Surgical applications of femtosecond lasers. J. Biophotonics 2009, 2, 557–572.

- Lehmann, U.; Kreipe, H. Laser-Assisted Microdissection and Isolation of DNA and RNA. In Breast Cancer Research Protocols; Brooks, S.A., Harris, A., Eds.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2006; pp. 65–75. ISBN 978-1-59259-969-1.

- Han, T.-S.; Oshima, M. Laser Microdissection of Cellular Compartments for Expression Analyses in Cancer Models. In Inflammation and Cancer: Methods and Protocols; Jenkins, B.J., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 143–153. ISBN 978-1-4939-7568-6.

- Odde, D.J.; Renn, M.J. Laser-guided direct writing for applications in biotechnology. Trends Biotechnol. 1999, 17, 385–389.

- Duan, B. State-of-the-Art Review of 3D Bioprinting for Cardiovascular Tissue Engineering. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2017, 45, 195–209.

- Zhang, Y.S.; Yue, K.; Aleman, J.; Mollazadeh-Moghaddam, K.; Bakht, S.M.; Yang, J.; Jia, W.; Dell’Erba, V.; Assawes, P.; Shin, S.R.; et al. 3D Bioprinting for Tissue and Organ Fabrication. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2017, 45, 148–163.

- Berns, M.W.; Aist, J.; Edwards, J.; Strahs, K.; Girton, J.; Mcneill, P.; Rattner, J.B.; Kitzes, M.; Liaw, L.; Siemens, A.; et al. Laser microsurgery in cell and developmental Biology. Science 1981, 213, 505–513.

- Thalhammer, S.; Lahr, G.; Clement-Sengewald, A.; Heckl, W.M.; Burgemeister, R.; Schütze, K. Laser microtools in cell biology and molecular medicine. Laser Phys. 2003, 13, 681–691.

- Kohli, V.; Elezzabi, A.Y. Prospects and developments in cell and embryo laser nanosurgery. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2009, 1, 11–25.

- Docchio, F.; Sacchi, C.; Marshall, J. Experimental Investigation of Optical Breakdown Thresholds in Ocular Media under Single Pulse Irradiation with Different Pulse Durations. Lasers Ophthalmol. 1986, 1, 83–93.

- Tadir, Y.; Douglas-Hamilton, D.H.; Douglas-Hamilton, D.H.; Douglas-Hamilton, D.H.; Douglas-Hamilton, D.H. Laser Effects in the Manipulation of Human Eggs and Embryos for In Vitro Fertilization. Methods Cell Biol. 2007, 82, 409–431.

- Sacchi, C.A. Laser-induced electric breakdown in water. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 1991, 8, 337.

- Sander, M.U.; Gudiksen, M.S.; Luther, K.; Troe, J. Liquid water ionization: Mechanistic implications of the H/D isotope effect in the geminate recombination of hydrated electrons. Chem. Phys. 2000, 258, 257–265.

- Elles, C.G.; Jailaubekov, A.E.; Crowell, R.A.; Bradforth, S.E. Excitation-energy dependence of the mechanism for two-photon ionization of liquid H2O and D2O from 8.3to12.4eV. J. Chem. Phys. 2006, 125, 044515.

- Göppert-Mayer, M. Über Elementarakte mit zwei Quantensprüngen. Ann. Phys. 1931, 401, 273–294.

- Keldysh, L.V. Ionization in the field of a strong electromagnetic wave. Sov. Phys. JETP 1965, 20, 1307–1314.

- Liang, X.-X.; Zhang, Z.; Vogel, A. Multi-rate-equation modeling of the energy spectrum of laser-induced conduction band electrons in water. Opt. Express 2019, 27, 4672.

- Ilina, I.; Sitnikov, D. From Zygote to Blastocyst: Application of Ultrashort Lasers in the Field of Assisted Reproduction and Developmental Biology. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 1897.

- Vogel, A.; Noack, J.; Hüttman, G.; Paltauf, G. Mechanisms of femtosecond laser nanosurgery of cells and tissues. Appl. Phys. B Lasers Opt. 2005, 81, 1015–1047.

- Linz, N.; Freidank, S.; Liang, X.X.; Vogel, A. Wavelength dependence of femtosecond laser-induced breakdown in water and implications for laser surgery. Phys. Rev. B 2016, 94, 024113.

- Vogel, A.; Venugopalan, V. Mechanisms of Pulsed Laser Ablation of Biological Tissues. Chem. Rev. 2003, 103, 577–644.

- Garrett, B.C.; Dixon, D.A.; Camaioni, D.M.; Chipman, D.M.; Johnson, M.A.; Jonah, C.D.; Kimmel, G.A.; Miller, J.H.; Rescigno, T.N.; Rossky, P.J.; et al. Role of Water in Electron-Initiated Processes and Radical Chemistry: Issues and Scientific Advances. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 355–390.

- Nikogosyan, D.N.; Oraevsky, A.A.; Rupasov, V.I. Two-photon ionization and dissociation of liquid water by powerful laser UV radiation. Chem. Phys. 1983, 77, 131–143.

- Boudaiffa, B. Resonant Formation of DNA Strand Breaks by Low-Energy (3 to 20 eV) Electrons. Science 2000, 287, 1658–1660.

- Zalessky, A.; Fedotov, Y.; Yashkina, E.; Nadtochenko, V.; Osipov, A.N. Immunocytochemical localization of XRCC1 and γH2AX foci induced by tightly focused femtosecond laser radiation in cultured human cells. Molecules 2021, 26, 4027.

- Quinto-Su, P.A.; Venugopalan, V. Mechanisms of Laser Cellular Microsurgery. In Methods in Cell Biology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; Volume 82, pp. 111–151. ISBN 0123706483.

- Paltauf, G.; Schmidt-Kloiber, H. Microcavity dynamics during laser-induced spallation of liquids and gels. Appl. Phys. A Mater. Sci. Process. 1996, 62, 303–311.

- Berns, M.W.; Cheng, W.K.; Floyd, A.D.; Ohnuki, Y. Chromosome Lesions Produced with an Argon Laser Microbeam without Dye Sensitization. Science 1971, 171, 903–905.

- König, K.; Riemann, I.; Fischer, P.; Halbhuber, K.J. Intracellular nanosurgery with near infrared femtosecond laser pulses. Cell. Mol. Biol. 1999, 45, 195–201.

- König, K.; Riemann, I.; Fritzsche, W. Nanodissection of human chromosomes with near-infrared femtosecond laser pulses. Opt. Lett. 2001, 26, 819–821.

- Daniel, J.C. Cleavage of Mammalian Ova inhibited by Visible Light. Nature 1964, 201, 316–317.

- Hirao, Y.; Yanagimachi, R. Detrimental effect of visible light on meiosis of mammalian eggs in vitro. J. Exp. Zool. 1978, 206, 365–369.

- Hegele-Hartung, C.; Schumacher, A.; Fischer, B. Effects of visible light and room temperature on the ultrastructure of preimplantation rabbit embryos: A time course study. Anat. Embryol. 1991, 183, 559–571.

- Handbook of Biological Confocal Microscopy; Pawley, J.B. (Ed.) Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1995; ISBN 978-1-4757-5350-9.

- Tosheva, K.L.; Yuan, Y.; Pereira, P.M.; Culley, S.; Henriques, R. Between life and death: Reducing phototoxicity in Super-Resolution Microscopy. Preprints 2019.

- Denk, W.; Strickler, J.; Webb, W. Two-photon laser scanning fluorescence microscopy. Science 1990, 248, 73–76.

- Barad, Y.; Eisenberg, H.; Horowitz, M.; Silberberg, Y. Nonlinear scanning laser microscopy by third harmonic generation. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1997, 70, 922–924.

- Campagnola, P.J.; Clark, H.A.; Mohler, W.A.; Lewis, A.; Loew, L.M. Second-harmonic imaging microscopy of living cells. J. Biomed. Opt. 2001, 6, 277.

- Evans, C.L.; Xie, X.S. Coherent Anti-Stokes Raman Scattering Microscopy: Chemical Imaging for Biology and Medicine. Annu. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2008, 1, 883–909.

- Parodi, V.; Jacchetti, E.; Osellame, R.; Cerullo, G.; Polli, D.; Raimondi, M.T. Nonlinear Optical Microscopy: From Fundamentals to Applications in Live Bioimaging. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 585363.

- Boyd, R. Nonlinear Optics, 1st ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1992; ISBN 9781483288239.

- Yelin, D.; Silberberg, Y. Laser scanning third-harmonic-generation microscopy in biology. Opt. Express 1999, 5, 169.

- Rehberg, M.; Krombach, F.; Pohl, U.; Dietzel, S. Label-Free 3D Visualization of Cellular and Tissue Structures in Intact Muscle with Second and Third Harmonic Generation Microscopy. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e28237.

- Sun, C.K. Higher harmonic generation microscopy. Adv. Biochem. Eng. Biotechnol. 2005, 95, 17–56.

- Nandakumar, P.; Kovalev, A.; Volkmer, A. Vibrational imaging based on stimulated Raman scattering microscopy. New J. Phys. 2009, 11, 033026.

- Cheng, J.-X.; Xie, X.S. Coherent Anti-Stokes Raman Scattering Microscopy: Instrumentation, Theory, and Applications. J. Phys. Chem. B 2004, 108, 827–840.

- Wang, S.; Larina, I.V.; Larin, K.V. Label-free optical imaging in developmental biology . Biomed. Opt. Express 2020, 11, 2017.

- Truong, T.V.; Supatto, W.; Koos, D.S.; Choi, J.M.; Fraser, S.E. Deep and fast live imaging with two-photon scanned light-sheet microscopy. Nat. Methods 2011, 8, 757–762.

- Lavagnino, Z.; Cella Zanacchi, F.; Ronzitti, E.; Diaspro, A. Two-photon excitation selective plane illumination microscopy (2PE-SPIM) of highly scattering samples: Characterization and application. Opt. Express 2013, 21, 5998.

- Wu, Q.; Kumar, N.; Velagala, V.; Zartman, J.J. Tools to reverse-engineer multicellular systems: Case studies using the fruit fly. J. Biol. Eng. 2019, 13, 33.

- Garcia, M.D.; Udan, R.S.; Hadjantonakis, A.-K.; Dickinson, M.E. Preparation of Postimplantation Mouse Embryos for Imaging: Figure 1. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2011, 2011, pdb.prot5594.

- Lopez, A.L.; Larina, I.V. Second harmonic generation microscopy of early embryonic mouse hearts. Biomed. Opt. Express 2019, 10, 2898.

- Abu-Siniyeh, A.; Al-Zyoud, W. Highlights on selected microscopy techniques to study zebrafish developmental biology. Lab. Anim. Res. 2020, 36, 12.

- Eum, J.; Kwak, J.; Kim, H.; Ki, S.; Lee, K.; Raslan, A.; Park, O.; Chowdhury, M.; Her, S.; Kee, Y.; et al. 3D Visualization of Developmental Toxicity of 2,4,6-Trinitrotoluene in Zebrafish Embryogenesis Using Light-Sheet Microscopy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1925.

- Chen, S.-Y.; Hsieh, C.-S.; Chu, S.-W.; Lin, C.-Y.; Ko, C.-Y.; Chen, Y.-C.; Tsai, H.-J.; Hu, C.-H.; Sun, C.-K. Noninvasive harmonics optical microscopy for long-term observation of embryonic nervous system development in vivo. J. Biomed. Opt. 2006, 11, 054022.

- Lin, C.-Y.; Hovhannisyan, V.; Wu, J.-T.; Lin, C.-W.; Chen, J.-H.; Lin, S.-J.; Dong, C.-Y. Label-free imaging of Drosophila larva by multiphoton autofluorescence and second harmonic generation microscopy. J. Biomed. Opt. 2008, 13, 050502.

- Débarre, D.; Supatto, W.; Pena, A.-M.; Fabre, A.; Tordjmann, T.; Combettes, L.; Schanne-Klein, M.-C.; Beaurepaire, E. Imaging lipid bodies in cells and tissues using third-harmonic generation microscopy. Nat. Methods 2006, 3, 47–53.

- Greenhalgh, C.; Stewart, B.; Cisek, R.; Prent, N.; Major, A.; Barzda, V. Dynamic investigation of Drosophila myocytes with second harmonic generation microscopy. In Photonics North 2006; Mathieu, P., Ed.; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2006; Volume 6343, p. 634308.

- Greenhalgh, C.; Prent, N.; Green, C.; Cisek, R.; Major, A.; Stewart, B.; Barzda, V. Influence of semicrystalline order on the second-harmonic generation efficiency in the anisotropic bands of myocytes. Appl. Opt. 2007, 46, 1852.

- Débarre, D.; Olivier, N.; Supatto, W.; Beaurepaire, E. Mitigating phototoxicity during multiphoton microscopy of live drosophila embryos in the 1.0–1.2 μm wavelength range. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e104250.

- Dou, W.; Zhang, D.; Jung, Y.; Cheng, J.X.; Umulis, D.M. Label-free imaging of lipid-droplet intracellular motion in early Drosophila embryos using femtosecond-stimulated Raman loss microscopy. Biophys. J. 2012, 102, 1666–1675.

- Lin, A.; Witvliet, D.; Hernandez-Nunez, L.; Linderman, S.W.; Samuel, A.D.T.; Venkatachalam, V. Imaging whole-brain activity to understand behaviour. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2022, 4, 292–305.

- Memeo, R.; Paiè, P.; Sala, F.; Castriotta, M.; Guercio, C.; Vaccari, T.; Osellame, R.; Bassi, A.; Bragheri, F. Automatic imaging of Drosophila embryos with light sheet fluorescence microscopy on chip. J. Biophotonics 2021, 14, e202000396.

- Karunendiran, A.; Cisek, R.; Tokarz, D.; Barzda, V.; Stewart, B.A. Examination of Drosophila eye development with third harmonic generation microscopy. Biomed. Opt. Express 2017, 8, 4504.

- Karunendiran, A.; Mirsanaye, K.; Stewart, B.A.; Barzda, V. Second Harmonic Generation Properties in Chiral Sarcomeres of Drosophila Larval Muscles. Front. Phys. 2022, 10, 758709.

- Golaraei, A.; Kontenis, L.; Karunendiran, A.; Stewart, B.A.; Barzda, V. Dual- and single-shot susceptibility ratio measurements with circular polarizations in second-harmonic generation microscopy. J. Biophotonics 2020, 13, e201960167.

- Karmenyan, A.V.; Shakhbazyan, A.K.; Sviridova-Chailakhyan, T.A.; Krivokharchenko, A.S.; Chiou, A.E.; Chailakhyan, L.M. Use of picosecond infrared laser for micromanipulation of early mammalian embryos. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2009, 76, 975–983.

More

Information

Subjects:

Developmental Biology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

768

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

21 Dec 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No