Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Lu, H.; Ying, K.; Shi, Y.; Liu, D.; Chen, Q. Bioprocessing by Decellularized Scaffold Biomaterials in Cultured Meat. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/38981 (accessed on 01 March 2026).

Lu H, Ying K, Shi Y, Liu D, Chen Q. Bioprocessing by Decellularized Scaffold Biomaterials in Cultured Meat. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/38981. Accessed March 01, 2026.

Lu, Hongyun, Keqin Ying, Ying Shi, Donghong Liu, Qihe Chen. "Bioprocessing by Decellularized Scaffold Biomaterials in Cultured Meat" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/38981 (accessed March 01, 2026).

Lu, H., Ying, K., Shi, Y., Liu, D., & Chen, Q. (2022, December 20). Bioprocessing by Decellularized Scaffold Biomaterials in Cultured Meat. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/38981

Lu, Hongyun, et al. "Bioprocessing by Decellularized Scaffold Biomaterials in Cultured Meat." Encyclopedia. Web. 20 December, 2022.

Copy Citation

As novel carrier biomaterials, decellularized scaffolds have promising potential in the development of cellular agriculture and edible cell-cultured meat applications. Decellularized scaffold biomaterials have characteristics of high biocompatibility, bio-degradation, biological safety and various bioactivities, which could potentially compensate for the shortcomings of synthetic bio-scaffold materials. They can provide suitable microstructure and mechanical support for cell adhesion, differentiation and proliferation.

cell-cultured meat

biomaterial

cellular agriculture

decellularized scaffolds

future food

1. Introduction

In the context of rapid population growth and economic development, there is a growing demand for and reliance on animal-derived protein. With the increasing demand for meat worldwide of more than 70%, resources on the earth will not provide enough meat to the world’s population by 2050 [1]. In order to replace the supply of animal meat and avoid the impact of livestock farming on soil destruction, water resources pollution and greenhouse gas emissions [2], it is essential to explore new sustainable production methods of eatable protein. Currently, synthesized meat is divided into two main types. The first one is meat analogs derived from plant and insect protein, and it uses protein-modified plant material to simulate the taste of meat and provide more sources of protein from insects [3]. However, due to the difference in nutritional value and meat flavor, this method cannot completely replace the current meat market. The second is cultured meat produced by in vitro proliferation and differentiation of animal stem cells [4], which has shown great potential and become an unstoppable trend for application in developing new meat resources. Laboratory-grown meat, also called cultured meat, clean meat, synthetic meat or in vitro meat [5], is a foodstuff formed by the proliferation of animal cells in vitro, and is mainly composed of skeletal muscle, fat and connective tissue [6]. In fact, the development of technologies such as stem cell isolation and identification, cell culture, and tissue engineering have gradually made it possible to culture meat in vitro.

Most mammalian cells are anchorage-dependent, which leads them to adhere to the surface of vector in cell proliferation. Previously, microcarriers were usually chemically synthesized polymers, which were manufactured on a large scale. However, related applications in cell expansion are relatively limited due to the lack of cell recognition sites [7]. Currently, microcarriers have the advantage of higher efficiency in material transport, leading to the developed culture system of adherent cells. On the other hand, micro-carriers have been used to amplify specific cells to produce monoclonal antibodies, proteins, vaccines, etc. A variety of research studies are focused on their potential applications in the field of regenerative medicine and tissue engineering. In fact, the simplest scaffolds are microcarriers, but mostly they play a role only during the suspension culture [8], thus the application of microcarriers in meat production has not been extensively studied [9]. To obtain cultured meat with a more realistic structure and texture, a scaffold that provides vascularization should be explored [8][10]. Generally speaking, cultured meat is produced by proliferating and adhering muscle cells to a carrier, then transferred to a bioreactor with a growth medium for culture. Cell-supporting scaffolds are intended to resemble the extracellular matrix (ECM) in structure and to some extent in biochemical properties that support cell structure and function in natural tissues [11]. Therefore, it is essential to find a suitable scaffold during the production of meat that meets different structural demands [12].

2. The Principles, Methods, and Application of Animal-Derived Decellularized Scaffolds

Animal decellularized scaffolds have played an important role in drug screening, allogeneic organ transplantation [13], regenerative medicine and tissue engineering, which also shows their great potential in meat production. Currently, animal-derived scaffolds have proven more suitable for the growth of myogenic cells because they are closer to the natural physiological properties of the cell growth environment, whereas synthetic biomaterials cannot be used to achieve tissue contraction [14]. Therefore, animal-derived decellularized scaffolds have a definite advantage over non-animal derived scaffold biomaterials in cultured meat and tissue engineering.

2.1. Application Principles of Animal-Derived Decellularized Scaffolds

After the decellularization process of animal tissues, cellular components, such as nuclear components and cytoplasm, are effectively removed, so that the decellularized scaffolds will not cause immune rejection and their biocompatibility is greatly improved [15]. The ECM has a dynamic, highly complex molecular structure that is rich in multiple components. These components can interact with each other and determine the form and function of the tissue [16]. While the cellular components are removed, most of the ECM components in the biomaterials are retained. These natural ECMs are rich in bioactive substances such as growth factors and cytokines, which can regulate the behaviors of certain cells, provide them with an appropriate growth microenvironment, and preserve the stem cell niche of natural tissues and regenerative capacity in vivo [17]. Therefore, decellularized scaffolds have strong bioactivity and the ability to induce cellular behaviors.

Most of the animal-derived decellularized scaffolds have specific microarchitectures and mechanical characterization, thus they can provide mechanical support for adherent cell adhesion and growth. Additionally, as a biological material for cultured meat production, the scaffold should not affect the edibility of the meat. Therefore, it is expected to be separated from the cell cultures or degraded at some stage. It would have more production advantages if the scaffold itself was edible and could be fully embedded in the meat without affecting its taste or sensory properties [9].

2.2. Preparation Methods of Animal-Derived Decellularized Scaffolds

The methods for preparation of animal-derived decellularized scaffolds, as a biomaterial used to produce edible meat, still have more space for exploration and improvement. In addition to the replacement ability of regenerative medicine, decellularized scaffolds for food meat production should meet the requirements of larger-scale production and lower cost, while their purity does not have to be as high as medical supplies [14]. Therefore, searching for the most appropriate methods for the preparation of animal-derived decellularized scaffolds and optimal culture conditions holds the key to the puzzle of cultured meat.

The methods of decellularization are mainly divided into physical methods, chemical methods, biological methods, and a combination of the above three treatments. Taken together, the common methods for preparation are summarized as demonstrated in Figure 1. Usually, physical methods, including crushing, stirring, ultrasonic processing, mechanical press, freezing and thawing, etc., can disrupt the cell membrane and release the contents. Due to the poor ability to decellularize the tissue alone, physical methods are mostly used in combination with other treatments [18]. After that, animal tissues should be further treated with chemical means such as sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and Triton X-100, and biological means such as nuclease and trypsin, to disrupt the interactions among DNA, proteins and lipids. Meanwhile, this joint approach also eliminated cellular debris and promoted detergent infiltration [19], so that the cellular components can be more efficiently eliminated. The decellularization can be evaluated by characterization such as hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining and DNA quantification, and the mechanical properties can be measured by nanoindentation and uniaxial compression testing, while scanning electron microscope (SEM) analysis, micro-CT and other techniques can be used to exhibit the structural properties of the scaffolds [20] (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The methods for the preparation of animal-derived decellularized scaffolds.

However, the precision and accuracy of decellularization is not completely tested. The mechanical properties and degradation rate of the decellularized scaffolds may not be sufficient for industry [21]. Therefore, a more convenient and efficient method of decellularization is worth exploring.

2.3. The Application of Animal-Derived Decellularized Scaffolds of Cultured Meat

The preparation of animal-derived decellularized scaffolds has been extensively studied and used in practice, and they are widely recognized for their value as promising, tissue-engineered biomaterials, especially for the production of allogeneic animal tissues with homologous decellularized scaffolds. Wang et al. [22] selected tendons to prepare decellularized scaffolds, and the tendon ECMs showed striking similarity to natural tendons in bioactive components, collagen arrangement and biomechanical characteristics. Lin et al. [23] concluded that both decellularized porcine subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue have a positive effect on the in vitro culture, morphological changes and differentiation of human adipose-derived stem cells. Sun et al. [24] compared decellularized ECMs derived from cartilage tissues to those derived from chondrocytes or stem cells, finding that the former was more likely to promote chondrogenic differentiation, while the latter contributes to cell proliferation and thus supports chondrogenesis.

Meanwhile, animal-derived decellularized scaffolds were extracted from single tissue in vitro culture, and their biomechanical characteristics were completely different [25]. Furthermore, Hanai et al. [26] completed the decellularization process of porcine tissues including cartilage, meniscus, ligament, tendon, muscle, synovium, fat pad, fat and bone, and found that the decellularized ECMs derived from different tissues contained different specific components, such as hydroxyproline, sulfated glycosaminoglycan and growth factors, which had different specific differentiation potential of skeletal tissues in cartilage, ligament and bone-derived ECMs. Because of the structural and functional similarity of ECMs between marine tissues and mammalian tissues, Lau et al. [27] prepared decellularized tilapia skin scaffolds, which have filled the gaps in commercially available non-mammalian decellularized scaffold products. The collagen of tilapia skin has a high denaturation temperature, so it is suitable for use as a biological material. Khajavi et al. [28] successfully promoted cartilage matrix synthesis through decellularized sturgeon fish cartilage. Adipose tissue contains a variety of ECM components including collagen, elastin, and biological macromolecules; it has significant potential for chondrogenic differentiation. Thus, Ibsirlioglu and Elçin [29] used adipose tissues for the preparation of decellularized scaffolds to promote chondrocyte adhesion, proliferation and differentiation. Various innovative studies, such as decellularized bovine intervertebral disc scaffolds supporting in vitro culture of multiple xenogeneic cells [30] and decellularized fish scale scaffolds for bone tissue engineering [31], have also demonstrated the increasing application potential.

All of these animal-derived decellularized scaffolds are derived from abundant animal tissues and have a wide variety of uses, including organ transplantation, drug screening, and stem cell differentiation [32]. In the food industry, some animal-derived decellularized scaffolds have required edibility, high bio-compatibility and affinity, although the related studies are relatively lacking. Additionally, the environmental requirements for the comprehensive utilization of processing by-products are driving the research direction to become much more innovative, which shows greater development of animal-derived decellularized scaffolds.

3. The Methods and Application of Plant-Derived Decellularized Scaffolds

The animal-derived decellularized scaffolds exhibit some disadvantages, such as higher costs and immunogenicity. Therefore, because of the abundant resources of numerous plants on earth, plant-derived decellularized scaffolds are much more environmentally friendly, abundant and diverse.

3.1. Principles of Plant-Derived Decellularized Scaffolds

Plant-derived biomaterials have fewer residual nuclear components after the decellularization process [15]. The major component of the scaffolds is cellulose, which constitutes the plant cell walls. After long and sufficient research, cellulose has been proven to be an abundant biomaterial with high biocompatibility. It is low-cost and easy to produce, and has natural porosity for in vitro 3D mammalian cell culture [33]. Additionally, its tight and ordered structure cannot be degraded by enzymatic reactions [34], resulting in lower immunogenicity and tougher mechanical properties. At the same time, most of these plants have delicate veins and high surface areas that can provide a good support platform for cell adhesion, and even retain and transport water [35] to promote cell growth. Although plant leaves lack blood vessels, they can be pre-vascularized scaffolds to preserve vascularity, support the metabolic activities of mammalian cells [36] and deliver nutrients to tissues [37] after treatment. Moreover, decellularized scaffolds derived from edible fruits and vegetables can satisfy the requirements of being natural and edible. Overall, plant-derived decellularized scaffolds have complex and detailed structure, low cost, and high production, and can support cell adhesion, expansion, and alignment. Such scaffolds have been demonstrated to be feasible for mammalian cell growth [34].

3.2. Preparation Strategy for Plant-Derived Decellularized Scaffolds

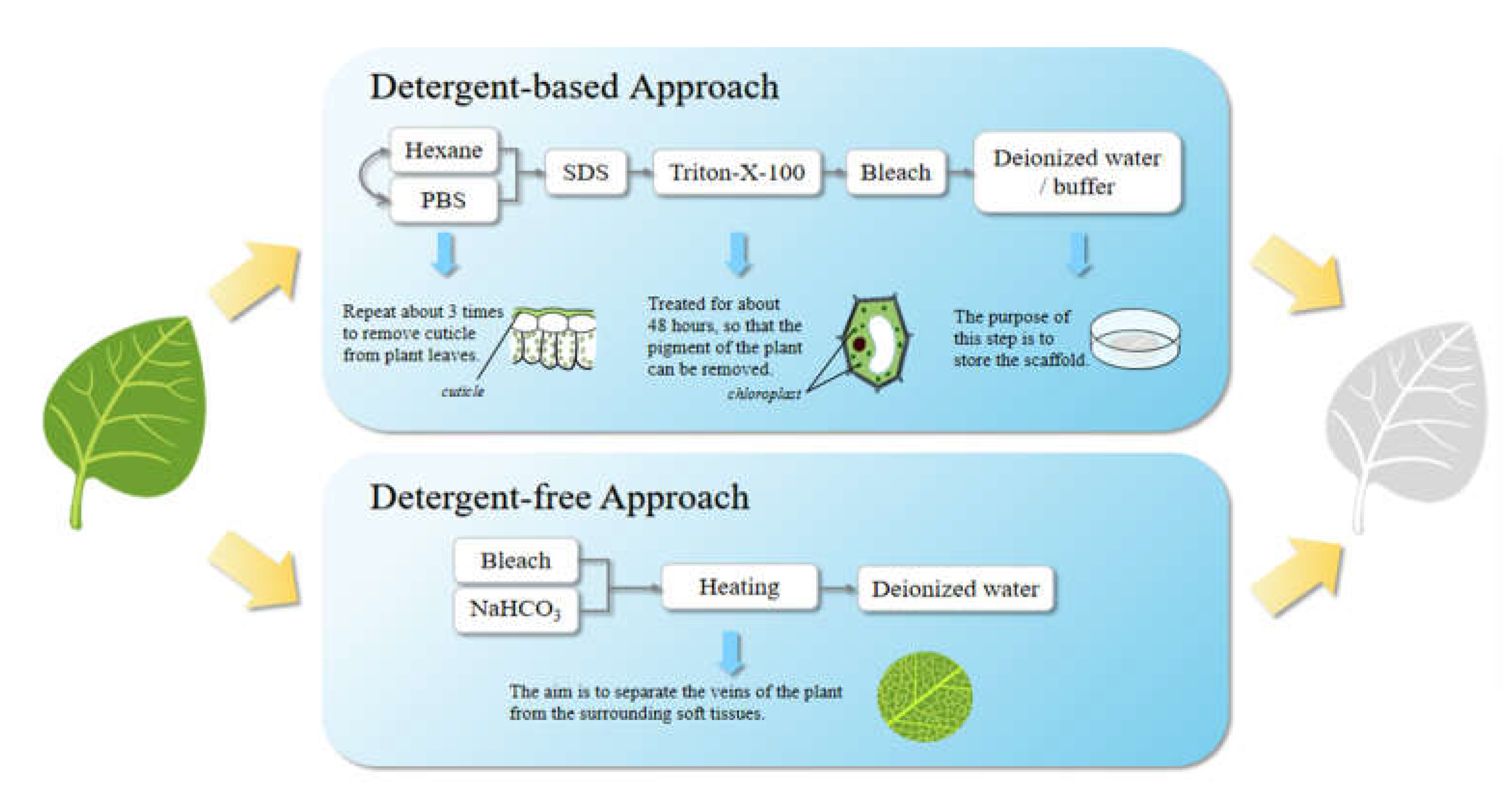

The raw material of plant-derived decellularized scaffolds should be fresh and free from mechanical damage. Continuous chemical treatment is the main method for the preparation of plant-derived decellularized scaffolds [38]. Two decellularization methods have proven to be effective. One is a detergent-based method, which is similar to the methods for the preparation of animal-derived decellularized scaffolds, and the other is a detergent-free decellularization method [35]. Different treatments will produce decellularized scaffolds with different properties and have different effects on the activity of cells grown on the scaffold.

The method of preparing plant-derived decellularized scaffolds is summarized in Figure 2. Among them, the first one is a detergent-based decellularization method. It can be subdivided into a perfusion method and immersion method, but they have no essential differences. First, leaf cuticles were removed by repeated treatment with hexane and phosphate buffer solution; secondly, phytopigments removal was achieved after the treatment with SDS water solution for about 5 days, 0.1% Triton-X-100 and 10% bleach solution for about 48 hours; thusly, the plant tissues will become white and transparent with clear veins. Finally, the scaffolds were immersed in deionized water or buffer solution and then stored there or lyophilized for storage. The steps of cuticles removal and phytopigments removal are not sequential. The second one is a detergent-free decellularization method. After the same pretreatment, the plant tissues were immersed in 5% bleach and a 3% sodium bicarbonate solution, and then heated and stirred in a fume hood. The plant veins can be separated from the surrounding soft tissues by such a treatment. When the temperature reaches 60 to 90 °C (The required temperature and treatment time depend on the plant species, sample sizes, etc.), the stirring speed should be gradually reduced to avoid damaging the tissue structure. Then, the scaffolds were placed in deionized water. Decellularized scaffolds can be evaluated by the roughness, porosity, surface area, hydrophilicity and mechanical properties of the scaffold surface [39].

Figure 2. The methods for the preparation of plant-derived decellularized scaffolds.

3.3. Application in Cultured Meat Process

Plant scaffolds have great application prospects because of the species richness, the structural similarity to animal tissues, high reproducibility and biocompatibility, which are not only well-established but also the goal of researchers to explore and improve. In fact, more and more research is providing a strong basis for these theories. In order to efficiently prepare higher yielding and quality decellularized scaffolds, Harris et al. [38] proposed a rapid and sterile method for the preparation, the supercritical carbon dioxide (ScCO2) method. Combining ScCO2 with 2% peroxyacetic acid could remove plant tissue within 4 hours and preserve the plant microstructure. Spinach leaves, mint leaves, parsley stems and celery stems were treated to confirm the effectiveness of the method. Phan et al. [40] used deoxyribonuclease I (DNase I) to prepare decellularized scaffolds and then verified their ability in cell attachment, spreading and proliferation. Jones et al. [41] explored the potential application of decellularized spinach as an economical, efficient and environmentally friendly scaffold, which can provide an edible substrate for the growth of bovine satellite cells and pioneer innovative targeted directions for cultured meat. Through specific experiments on spinach, parsley, artemisia annua leaves and peanut hairy roots, Gershlak et al. [37] drew a conclusion with practical significance that the structural diversity of plants can be well adapted to the complexity of animal tissues, and therefore different plant tissues have their most suitable application directions for tissue engineering. Various plant-derived decellularized scaffolds can be selected for the in vitro culture of the same animal tissues. For the in vitro culture of skeletal muscle and bone tissue, Cheng et al. [42] used various vegetables, such as carrot, broccoli, cucumber, potato, apple, asparagus, green onion, leek and celery, to prepare decellularized scaffolds. The decellularized green onion scaffold has shown a greater ability to promote the arrangement and differentiation of skeletal muscle cells. By comparing and evaluating the decellularized scaffolds of apples, cauliflower, bell peppers, carrots, persimmons, and dates, Lee et al. [43] concluded that the decellularized apple scaffold with high biocompatibility and low costs can best promote the growth and differentiation of osteoblasts. Negrini et al. [44] showed that decellularized carrot scaffolds had greater potential than the decellularized scaffolds of apples and celery in promoting osteoclast adhesion, proliferation and differentiation. Salehi et al. preferred spinach leaves [39] and onion epidermis [32], while Aswathy et al. [45] explored the application of bamboo stems for this purpose. Worth mention, Allan et al. [46] studied grass blades. The surface of such a plant is full of grooves; therefore, it is a natural structure with directional and topographical features that can maintain cell viability, induce cell alignment, and support cell attachment and proliferation, and the differentiation of murine C2C12 myoblasts. This result suggested that some plant-derived scaffolds with special structures (e.g., repetitive grooves) may be more suitable for the alignment of muscle fibers [47]. Unlike most studies that focused on the edibility and degradability of scaffolds, Ong et al. [48] focused on the ability of scaffolds to improve the visual appearance of cell-cultured meat. For example, the jackfruit scaffold is more acceptable to consumers due to the oxidation of its internal natural polyphenols, which can induce flesh-like color and produce a rich marbling visual on meat cuts.

Additionally, plant-derived decellularized scaffolds have also been the focus of the direction of organ regeneration, such as in vitro culture of vascular, myocardial and renal tubules [49]. While others have focused on applications beyond the cultivation of animal tissues in vitro. These studies showed a low association with the scope of in vitro cultured meat reviewed in this paper, and therefore were not further described here. The results reported above illustrate that plant-derived decellularized scaffolds have continued room for exploration and high research value. However, while the application potential of plant-derived decellularization is receiving increasing attention, Lacombe et al. [50] pointed out that compared with standard cell culture models, plant-derived decellularized scaffolds will alter cell behavior, which can affect cell morphology, bioactivity and the proliferation rate. The results also forewarn us that this technique is not yet mature enough to be placed into large-scale production and application. Thus, many studies are further needed to address various issues that may be confronted within the practical production environment.

References

- Post, M.J.; Levenberg, S.; Kaplan, D.L.; Genovese, N.; Fu, J.A.; Bryant, C.J.; Negowetti, N.; Verzijden, K.; Moutsatsou, P. Scientific, sustainability and regulatory challenges of cultured meat. Nat. Food 2020, 1, 403–415.

- Ben-Arye, T.; Levenberg, S. Tissue Engineering for Clean Meat Production. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2019, 3.

- Ismail, I.; Hwang, Y.H.; Joo, S.T. Meat analog as future food: A review. J. Anim. Sci. Technol. 2020, 62, 111–120.

- Rubio, N.R.; Xiang, N.; Kaplan, D.L. Plant-based and cell-based approaches to meat production. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1.

- Warner, R.D. Review: Analysis of the process and drivers for cellular meat production. Animal 2019, 13, 3041–3058.

- Rischer, H.; Szilvay, G.R.; Oksman-Caldentey, K.M. Cellular agriculture-industrial biotechnology for food and materials. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2020, 61, 128–134.

- Djisalov, M.; Knezic, T.; Podunavac, I.; Zivojevic, K.; Radonic, V.; Knezevic, N.Z.; Bobrinetskiy, I.; Gadjanski, I. Cultivating Multidisciplinarity: Manufacturing and Sensing Challenges in Cultured Meat Production. Biology 2021, 10, 204.

- Bomkamp, C.; Skaalure, S.C.; Fernando, G.F.; Ben-Arye, T.; Swartz, E.W.; Specht, E.A. Scaffolding Biomaterials for 3D Cultivated Meat: Prospects and Challenges. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, 1–40.

- Bodiou, V.; Moutsatsou, P.; Post, M.J. Microcarriers for Upscaling Cultured Meat Production. Front. Nutr. 2020, 7.

- Seah, J.S.H.; Singh, S.; Tan, L.P.; Choudhury, D. Scaffolds for the manufacture of cultured meat. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2022, 42, 311–323.

- Cai, S.; Wu, C.; Yang, W.; Liang, W.; Yu, H.; Liu, L. Recent advance in surface modification for regulating cell adhesion and behaviors. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2020, 9, 971–989.

- Handral, H.K.; Tay, S.H.; Chan, W.W.; Choudhury, D. 3D Printing of cultured meat products. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 272–281.

- Wei, Y.R.X.; Zhang, Y.J. Decellularized Liver Scaffold for Liver Regeneration. Methods Mol. Biol. 2018, 1577, 11–23.

- Stephens, N.; Di Silvio, L.; Dunsford, I.; Ellis, M.; Glencross, A.; Sexton, A. Bringing cultured meat to market: Technical, socio-political, and regulatory challenges in cellular agriculture. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 78, 155–166.

- Predeina, A.L.; Dukhinova, M.S.; Vinogradov, V.V. Bioreactivity of decellularized animal, plant, and fungal scaffolds: Perspectives for medical applications. J. Mater. Chem. B 2020, 8, 10010–10022.

- Rajab, T.K.; O’Malley, T.J.; Tchantchaleishvili, V. Decellularized scaffolds for tissue engineering: Current status and future perspective. Artif. Organs 2020, 44, 1031–1043.

- Saleh, T.M.; Ahmed, E.A.; Yu, L.; Kwak, H.H.; Hussein, K.H.; Park, K.M.; Kang, B.J.; Choi, K.Y.; Kang, K.S.; Woo, H.M. Incorporation of nanoparticles into transplantable decellularized matrices: Applications and challenges. Int. J. Organs 2018, 41, 421–430.

- Gilbert, T.W.; Sellaro, T.L.; Badylak, S.F. Decellularization of tissues and organs. Biomaterials 2006, 27, 3675–3683.

- Xia, C.; Mei, S.; Gu, C.; Zheng, L.; Fang, C.; Shi, Y.; Wu, K.; Lu, T.; Jin, Y.; Lin, X.; et al. Decellularized cartilage as a prospective scaffold for cartilage repair. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2019, 101, 588–595.

- Chen, G.; Lv, Y.M.i.m.b. Decellularized Bone Matrix Scaffold for Bone Regeneration. Methods Mol Biol. 2017, 1577, 239–254.

- Liao, J.; Xu, B.; Zhang, R.H.; Fan, Y.B.; Xie, H.Q.; Li, X.M. Applications of decellularized materials in tissue engineering: Advantages, drawbacks and current improvements, and future perspectives. J. Mater. Chem. B 2020, 8, 10023–10049.

- Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Song, L.; Chen, J.; Ma, Y.; Chen, Y.; Fan, S.; Su, M.; Lin, X. Decellularized tendon as a prospective scaffold for tendon repair. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 77, 1290–1301.

- Lin, M.H.; Ge, J.B.; Wang, X.C.; Dong, Z.Q.; Xing, M.; Lu, F.; He, Y.F. Biochemical and biomechanical comparisions of decellularized scaffolds derived from porcine subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue. J. Tissue Eng. 2019, 10, 1–14.

- Sun, Y.; Yan, L.; Chen, S.; Pei, M. Functionality of decellularized matrix in cartilage regeneration: A comparison of tissue versus cell sources. Acta Biomater. 2018, 74, 56–73.

- Porzionato, A.; Stocco, E.; Barbon, S.; Grandi, F.; Macchi, V.; De Caro, R. Tissue-Engineered Grafts from Human Decellularized Extracellular Matrices: A Systematic Review and Future Perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 4117.

- Hanai, H.; Jacob, G.; Nakagawa, S.; Tuan, R.S.; Nakamura, N.; Shimomura, K. Potential of Soluble Decellularized Extracellular Matrix for Musculoskeletal Tissue Engineering-Comparison of Various Mesenchymal Tissues. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 581972.

- Lau, C.S.; Hassanbhai, A.; Wen, F.; Wang, D.; Chanchareonsook, N.; Goh, B.T.; Yu, N.; Teoh, S.-H. Evaluation of decellularized tilapia skin as a tissue engineering scaffold. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2019, 13, 1779–1791.

- Khajavi, M.; Hajimoradloo, A.; Zandi, M.; Pezeshki-Modaress, M.; Bonakdar, S.; Zamani, A. Fish cartilage: A promising source of biomaterial for biological scaffold fabrication in cartilage tissue engineering. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A. 2021, 109, 1737–1750.

- Ibsirlioglu, T.; Elçin, A.E.; Elçin, Y.M. Decellularized biological scaffold and stem cells from autologous human adipose tissue for cartilage tissue engineering. Methods 2020, 171, 97–107.

- Chan, L.K.Y.; Leung, V.Y.L.; Tam, V.; Lu, W.W.; Sze, K.Y.; Cheung, K.M.C. Decellularized bovine intervertebral disc as a natural scaffold for xenogenic cell studies. Acta Biomater. 2013, 9, 5262–5272.

- Kara, A.; Tamburaci, S.; Tihminlioglu, F.; Havitcioglu, H. Bioactive fish scale incorporated chitosan biocomposite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 130, 266–279.

- Hussein, K.H.; Park, K.-M.; Kang, K.-S.; Woo, H.-M. Biocompatibility evaluation of tissue-engineered decellularized scaffolds for biomedical application. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2016, 67, 766–778.

- Modulevsky, D.J.; Lefebvre, C.; Haase, K.; Al-Rekabi, Z.; Pelling, A.E. Apple Derived Cellulose Scaffolds for 3D Mammalian Cell Culture. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e97835.

- Fontana, G.; Gershlak, J.; Adamski, M.; Lee, J.S.; Matsumoto, S.; Le, H.D.; Binder, B.; Wirth, J.; Gaudette, G.; Murphy, W.L. Biofunctionalized Plants as Diverse Biomaterials for Human Cell Culture. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2017, 6, 1601225.

- Adamski, M.; Fontana, G.; Gershlak, J.R.; Gaudette, G.R.; Le, H.D.; Murphy, W.L. Two Methods for Decellularization of Plant Tissues for Tissue Engineering Applications. Jove-J. Vis. Exp. 2018, 135, 57586.

- Walawalkar, S.; Almelkar, S. Fabricating a pre-vascularized large-sized metabolically-supportive scaffold using Brassica oleracea leaf. J. Biomater. Appl. 2021, 36, 165–178.

- Gershlak, J.R.; Hernandez, S.; Fontana, G.; Perreault, L.R.; Hansen, K.J.; Larson, S.A.; Binder, B.Y.K.; Dolivo, D.M.; Yang, T.; Dominko, T.; et al. Crossing kingdoms: Using decellularized plants as perfusable tissue engineering scaffolds. Biomaterials 2017, 125, 13–22.

- Harris, A.F.; Lacombe, J.; Liyanage, S.; Han, M.Y.; Wallace, E.; Karsunky, S.; Abidi, N.; Zenhausern, F. Supercritical carbon dioxide decellularization of plant material to generate 3D biocompatible scaffolds. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–3.

- Salehi, A.; Mobarhan, M.A.; Mohammadi, J.; Shahsavarani, H.; Shokrgozar, M.A.; Alipour, A. Efficient mineralization and osteogenic gene overexpression of mesenchymal stem cells on decellularized spinach leaf scaffold. Gene 2020, 757, 144852.

- Phan, N.V.; Wright, T.; Rahman, M.M.; Xu, J.F.; Coburn, J.M. In Vitro Biocompatibility of Decellularized Cultured Plant Cell-Derived Matrices. Acs Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 6, 822–832.

- Jones, J.D.; Rebello, A.S.; Gaudette, G.R. Decellularized spinach: An edible scaffold for laboratory-grown meat. Food Biosci. 2021, 41, 100986.

- Cheng, Y.W.; Shiwarski, D.J.; Ball, R.L.; Whitehead, K.A.; Feinberg, A.W. Engineering Aligned Skeletal Muscle Tissue Using Decellularized Plant-Derived Scaffolds. Acs Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 6, 3046–3054.

- Lee, J.; Jung, H.; Park, N.; Park, S.H.; Ju, J.H. Induced Osteogenesis in Plants Decellularized Scaffolds. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1.

- Negrini, N.C.; Toffoletto, N.; Fare, S.; Altomare, L. Plant Tissues as 3D Natural Scaffolds for Adipose, Bone and Tendon Tissue Regeneration. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 723.

- Aswathy, S.H.; Mohan, C.C.; Unnikrishnan, P.S.; Krishnan, A.G.; Nair, M.B. Decellularization and oxidation process of bamboo stem enhance biodegradation and osteogenic differentiation. Mater. Sci. Eng. C-Mater. Biol. Appl. 2021, 119, 11500.

- Allan, S.J.; Ellis, M.J.; De Bank, P.A. Decellularized grass as a sustainable scaffold for skeletal muscle tissue engineering. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2021, 109, 2471–2482.

- Zhu, Y.W.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, S.Y.; Zhang, J.F.; Fan, S.W.; Lin, X.F. Current Advances in the Development of Decellularized Plant Extracellular Matrix. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 650.

- Ong, S.J.; Loo, L.; Pang, M.; Tan, R.; Teng, Y.; Lou, X.M.; Chin, S.K.; Naik, M.Y.; Yu, H. Decompartmentalisation as a simple color manipulation of plant-based marbling meat alternatives. Biomaterials 2021, 277, 1015–10125.

- Jansen, K.; Evangelopoulou, M.; Casellas, C.P.; Abrishamcar, S.; Jansen, J.; Vermonden, T.; Masereeuw, R. Spinach and Chive for Kidney Tubule Engineering: The Limitations of Decellularized Plant Scaffolds and Vasculature. Aaps 2021, 23, 1–7.

- Lacombe, J.; Harris, A.F.; Zenhausern, R.; Karsunsky, S.; Zenhausern, F. Plant-Based Scaffolds Modify Cellular Response to Drug and Radiation Exposure Compared to Standard Cell Culture Models. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 932.

More

Information

Subjects:

Food Science & Technology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.2K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

20 Dec 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No