| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ion Udroiu | -- | 2706 | 2022-12-19 11:26:25 | | | |

| 2 | Conner Chen | Meta information modification | 2706 | 2022-12-20 11:22:48 | | |

Video Upload Options

Telomerase is the only known eukaryotic-specific enzyme with reverse transcriptase activity, which adds telomeric repeats at the ends of linear chromosomes. In this way, it counteracts telomere shortening and cellular replicative senescence. Telomerase consists of a catalytic protein subunit with reverse transcriptase activity (TERT), and an essential RNA component known as telomerase RNA component (TERC) that contains a template for the synthesis of telomeric DNA, as well as additional proteins (dyskerin, NHP2, NOP10 and GAR1 in vertebrates) that play crucial roles in its biogenesis, localization, and regulation. Beside its telomere-elongating activity, a growing number of studies have evidenced non-telomeric functions.

1. Introduction

2. Telomerase: Function and Components

2.1. Telomerase Function

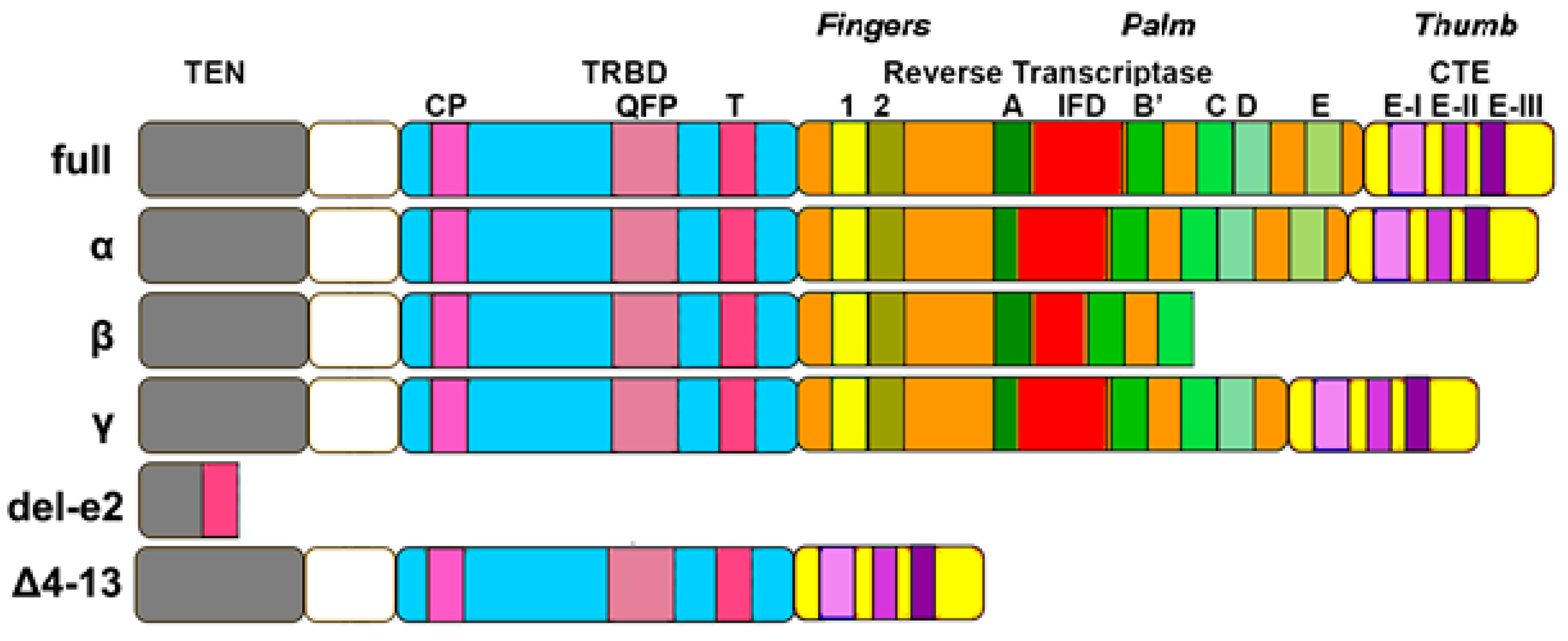

2.2. TERT Structure

2.3. TERC Structure

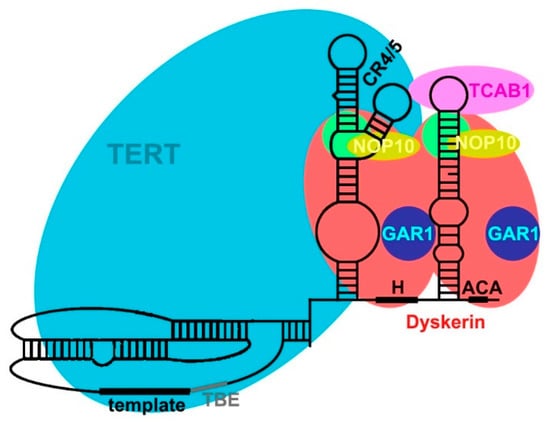

2.4. Secondary and Accessory Proteins

2.5. Has Telomerase Any Non-Telomeric Function?

2.5.1. Addition of Telomeric Repeats at Double-Strand Break Sites?

2.5.2. NOP2-Dependent Recruitment of Telomerase to Cyclin D1 Promoter

References

- Greider, C.W.; Blackburn, E.H. Identification of a Specific Telomere Terminal Transferase Activity in Tetrahymena Extracts. Cell 1985, 43, 405–413.

- Olovnikov, A.M. Principle of Marginotomy in Template Synthesis of Polynucleotides. Dokl. Akad. Nauk SSSR 1971, 201, 1496–1499.

- Shay, J.W.; Wright, W.E. Telomerase: A Target for Cancer Therapeutics. Cancer Cell 2002, 2, 257–265.

- Morrison, S.J.; Prowse, K.R.; Ho, P.; Weissman, I.L. Telomerase Activity in Hematopoietic Cells Is Associated with Self-Renewal Potential. Immunity 1996, 5, 207–216.

- Härle-Bachor, C.; Boukamp, P. Telomerase Activity in the Regenerative Basal Layer of the Epidermis Inhuman Skin and in Immortal and Carcinoma-Derived Skin Keratinocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 6476–6481.

- Colitz, C.M.H.; Davidson, M.G.; McGahan, M.C. Telomerase Activity in Lens Epithelial Cells of Normal and Cataractous Lenses. Exp. Eye Res. 1999, 69, 641–649.

- Udroiu, I.; Russo, V.; Persichini, T.; Colasanti, M.; Sgura, A. Telomeres and Telomerase in Basal Metazoa. Invertebr. Surviv. J. 2017, 14, 233–240.

- Autexier, C.; Lue, N.F. The Structure and Function of Telomerase Reverse Transcriptase. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2006, 75, 493–517.

- Greider, C.W.; Blackburn, E.H. A Telomeric Sequence in the RNA of Tetrahymena Telomerase Required for Telomere Repeat Synthesis. Nature 1989, 337, 331–337.

- Venteicher, A.S.; Artandi, S.E. TCAB1: Driving Telomerase to Cajal Bodies. Cell Cycle 2009, 8, 1329–1331.

- Hockemeyer, D.; Collins, K. Control of Telomerase Action at Human Telomeres. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2015, 22, 848–852.

- Zhang, Q.; Kim, N.K.; Feigon, J. Architecture of Human Telomerase RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 20325–20332.

- Morin, G.B. The Human Telomere Terminal Transferase Enzyme Is a Ribonucleoprotein That Synthesizes TTAGGG Repeats. Cell 1989, 59, 521–529.

- Greider, C.W. Telomerase Is Processive. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1991, 11, 4572–4580.

- Weise, J.M.; Günes, C. Differential Regulation of Human and Mouse Telomerase Reverse Transcriptase (TERT) Promoter Activity during Testis Development. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2009, 76, 309–317.

- Avilion, A.A.; Piatyszek, M.A.; Gupta, J.; Shay, J.W.; Bacchetti, S.; Greider, C.W. Human Telomerase RNA and Telomerase Activity in Immortal Cell Lines and Tumor Tissues. Cancer Res. 1996, 56.

- Castle, J.C.; Armour, C.D.; Löwer, M.; Haynor, D.; Biery, M.; Bouzek, H.; Chen, R.; Jackson, S.; Johnson, J.M.; Rohl, C.A.; et al. Digital Genome-Wide NcRNA Expression, Including SnoRNAs, across 11 Human Tissues Using PolyA-Neutral Amplification. PLoS One 2010, 5.

- Hartmann, N.; Reichwald, K.; Lechel, A.; Graf, M.; Kirschner, J.; Dorn, A.; Terzibasi, E.; Wellner, J.; Platzer, M.; Rudolph, K.L.; et al. Telomeres Shorten While Tert Expression Increases during Ageing of the Short-Lived Fish Nothobranchius Furzeri. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2009, 130, 290–296.

- Agarwal, S.; Loh, Y.H.; McLoughlin, E.M.; Huang, J.; Park, I.H.; Miller, J.D.; Huo, H.; Okuka, M.; Dos Reis, R.M.; Loewer, S.; et al. Telomere Elongation in Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells from Dyskeratosis Congenita Patients. Nature 2010, 464, 292–296.

- Weinrich, S.L.; Pruzan, R.; Ma, L.; Ouellette, M.; Tesmer, V.M.; Holt, S.E.; Bodnar, A.G.; Lichtsteiner, S.; Kim, N.W.; Trager, J.B.; et al. Reconstitution of Human Telomerase with the Template RNA Component HTR and the Catalytic Protein Subunit HTRT. Nat. Genet. 1997, 17, 498–502.

- Miller, M.C.; Liu, J.K.; Collins, K. Template Definition by Tetrahymena Telomerase Reverse Transcriptase. EMBO J. 2000, 19, 4412–4422.

- Moriarty, T.J.; Huard, S.; Dupuis, S.; Autexier, C. Functional Multimerization of Human Telomerase Requires an RNA Interaction Domain in the N Terminus of the Catalytic Subunit. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002, 22, 1253–1265.

- Sealey, D.C.F.; Zheng, L.; Taboski, M.A.S.; Cruickshank, J.; Ikura, M.; Harrington, L.A. The N-Terminus of HTERT Contains a DNA-Binding Domain and Is Required for Telomerase Activity and Cellular Immortalization. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, 2019–2035.

- Lai, C.K.; Mitchell, J.R.; Collins, K. RNA Binding Domain of Telomerase Reverse Transcriptase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001, 21, 990–1000.

- Moriarty, T.J.; Marie-Egyptienne, D.T.; Autexier, C. Functional Organization of Repeat Addition Processivity and DNA Synthesis Determinants in the Human Telomerase Multimer. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004, 24, 3720–3733.

- Mitchell, J.R.; Collins, K. Human Telomerase Activation Requires Two Independent Interactions between Telomerase RNA and Telomerase Reverse Transcriptase. Mol. Cell 2000, 6, 361–371.

- Friedman, K.L.; Cech, T.R. Essential Functions of Amino-Terminal Domains in the Yeast Telomerase Catalytic Subunit Revealed by Selection for Viable Mutants. Genes Dev. 1999, 13, 2863–2874.

- Willers, H.; McCarthy, E.E.; Wu, B.; Wunsch, H.; Tang, W.; Taghian, D.G.; Xia, F.; Powell, S.N. Dissociation of P53-Mediated Suppression of Homologous Recombination from G1/S Cell Cycle Checkpoint Control. Oncogene 2000, 19, 632–639.

- Beattie, T.L.; Zhou, W.; Robinson, M.O.; Harrington, L. Reconstitution of Human Telomerase Activity in Vitro. Curr. Biol. 1998, 8, 177–180.

- Nakamura, T.M.; Morin, G.B.; Chapman, K.B.; Weinrich, S.L.; Andrews, W.H.; Lingner, J.; Harley, C.B.; Cech, T.R. Telomerase Catalytic Subunit Homologs from Fission Yeast and Human. Science 1997, 277, 955–959.

- Bosoy, D.; Lue, N.F. Functional Analysis of Conserved Residues in the Putative “Finger” Domain of Telomerase Reverse Transcriptase. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 46305–46312.

- Xie, M.; Podlevsky, J.D.; Qi, X.; Bley, C.J.; Chen, J.J.L. A Novel Motif in Telomerase Reverse Transcriptase Regulates Telomere Repeat Addition Rate and Processivity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, 1982–1996.

- Gillis, A.J.; Schuller, A.P.; Skordalakes, E. Structure of the Tribolium Castaneum Telomerase Catalytic Subunit TERT. Nature 2008, 455, 633–637.

- Seimiya, H.; Sawada, H.; Muramatsu, Y.; Shimizu, M.; Ohko, K.; Yamane, K.; Tsuruo, T. Involvement of 14-3-3 Proteins in Nuclear Localization of Telomerase. EMBO J. 2000, 19, 2652–2661.

- Haendeler, J.; Hoffmann, J.; Brandes, R.P.; Zeiher, A.M.; Dimmeler, S. Hydrogen Peroxide Triggers Nuclear Export of Telomerase Reverse Transcriptase via Src Kinase Family-Dependent Phosphorylation of Tyrosine 707. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003, 23, 4598–4610.

- Ye, A.J.; Romero, D.P. Phylogenetic Relationships amongst Tetrahymenine Ciliates Inferred by a Comparison of Telomerase RNAs. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2002, 52, 2297–2302.

- Chakrabarti, K.; Pearson, M.; Grate, L.; Sterne-Weiler, T.; Deans, J.; Donohue, J.P.; Ares, M. Structural RNAs of Known and Unknown Function Identified in Malaria Parasites by Comparative Genomics and RNA Analysis. RNA 2007, 13, 1923–1939.

- Song, J.; Logeswaran, D.; Castillo-González, C.; Li, Y.; Bose, S.; Aklilu, B.B.; Ma, Z.; Polkhovskiy, A.; Chen, J.J.L.; Shippen, D.E. The Conserved Structure of Plant Telomerase RNA Provides the Missing Link for an Evolutionary Pathway from Ciliates to Humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 24542–24550.

- Qi, X.; Li, Y.; Honda, S.; Hoffmann, S.; Marz, M.; Mosig, A.; Podlevsky, J.D.; Stadler, P.F.; Selker, E.U.; Chen, J.J.L. The Common Ancestral Core of Vertebrate and Fungal Telomerase RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, 450–462.

- Logeswaran, D.; Li, Y.; Podlevsky, J.D.; Chen, J.J.L. Monophyletic Origin and Divergent Evolution of Animal Telomerase RNA. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 215–228.

- Podlevsky, J.D.; Chen, J.J.L. Evolutionary Perspectives of Telomerase RNA Structure and Function. RNA Biol. 2016, 13, 720–732.

- Chen, J.L.; Blasco, M.A.; Greider, C.W. Secondary Structure of Vertebrate Telomerase RNA. Cell 2000, 100, 503–514.

- Theimer, C.A.; Feigon, J. Structure and Function of Telomerase RNA. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2006, 16, 307–318.

- Chen, J.L.; Greider, C.W. Template Boundary Definition in Mammalian Telomerase. Genes Dev. 2003, 17, 2747–2752.

- Hossain, S.; Singh, S.; Lue, N.F. Functional Analysis of the C-Terminal Extension of Telomerase Reverse Transcriptase. A Putative “Thumb” Domain. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 36174–36180.

- Förstemann, K.; Lingner, J. Telomerase Limits the Extent of Base Pairing between Template RNA and Telomeric DNA. EMBO Rep. 2005, 6, 361–366.

- Brown, Y.; Abraham, M.; Pearl, S.; Kabaha, M.M.; Elboher, E.; Tzfati, Y. A Critical Three-Way Junction Is Conserved in Budding Yeast and Vertebrate Telomerase RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, 6280–6289.

- Blackburn, E.H.; Collins, K. Telomerase: An RNP Enzyme Synthesizes DNA. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2011, 3, 1–9.

- Huang, J.; Brown, A.F.; Wu, J.; Xue, J.; Bley, C.J.; Rand, D.P.; Wu, L.; Zhang, R.; Chen, J.J.L.; Lei, M. Structural Basis for Protein-RNA Recognition in Telomerase. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2014, 21, 507–512.

- Mitchell, J.R.; Cheng, J.; Collins, K. A Box H/ACA Small Nucleolar RNA-like Domain at the Human Telomerase RNA 3’ End. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999, 19, 567–576.

- Vulliamy, T.J.; Marrone, A.; Knight, S.W.; Walne, A.; Mason, P.J.; Dokal, I. Mutations in Dyskeratosis Congenita: Their Impact on Telomere Length and the Diversity of Clinical Presentation. Blood 2006, 107, 2680–2685.

- Li, H. Unveiling Substrate RNA Binding to H/ACA RNPs: One Side Fits All. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2008, 18, 78–85.

- Reichow, S.L.; Hamma, T.; Ferré-D’Amaré, A.R.; Varani, G. The Structure and Function of Small Nucleolar Ribonucleoproteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, 1452–1464.

- Cristofari, G.; Adolf, E.; Reichenbach, P.; Sikora, K.; Terns, R.M.; Terns, M.P.; Lingner, J. Human Telomerase RNA Accumulation in Cajal Bodies Facilitates Telomerase Recruitment to Telomeres and Telomere Elongation. Mol. Cell 2007, 27, 882–889.

- Theimer, C.A.; Jády, B.E.; Chim, N.; Richard, P.; Breece, K.E.; Kiss, T.; Feigon, J. Structural and Functional Characterization of Human Telomerase RNA Processing and Cajal Body Localization Signals. Mol. Cell 2007, 27, 869–881.

- Kiss, T.; Fayet-Lebaron, E.; Jády, B.E. Box H/ACA Small Ribonucleoproteins. Mol. Cell 2010, 37, 597–606.

- Egan, E.D.; Collins, K. Specificity and Stoichiometry of Subunit Interactions in the Human Telomerase Holoenzyme Assembled in Vivo. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2010, 30, 2775–2786.

- Lafontaine, D.L.J.; Bousquet-Antonelli, C.; Henry, Y.; Caizergues-Ferrer, M.; Tollervey, D. The Box H + ACA SnoRNAs Carry Cbf5p, the Putative RRNA Pseudouridine Synthase. Genes Dev. 1998, 12, 527–537.

- Ganot, P.; Bortolin, M.L.; Kiss, T. Site-Specific Pseudouridine Formation in Preribosomal RNA Is Guided by Small Nucleolar RNAs. Cell 1997, 89, 799–809.

- Kiss, A.M.; Jády, B.E.; Darzacq, X.; Verheggen, C.; Bertrand, E.; Kiss, T. A Cajal Body-Specific Pseudouridylation Guide RNA Is Composed of Two Box H/ACA SnoRNA-like Domains. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 4643–4649.

- Richard, P.; Darzacq, X.; Bertrand, E.; Jády, B.E.; Verheggen, C.; Kiss, T. A Common Sequence Motif Determines the Cajal Body-Specific Localization of Box H/ACA ScaRNAs. EMBO J. 2003, 22, 4283–4293.

- Wang, C.; Meier, U.T. Architecture and Assembly of Mammalian H/ACA Small Nucleolar and Telomerase Ribonucleoproteins. EMBO J. 2004, 23, 1857–1867.

- Grozdanov, P.N.; Roy, S.; Kittur, N.; Meier, U.T. SHQ1 Is Required Prior to NAF1 for Assembly of H/ACA Small Nucleolar and Telomerase RNPs. RNA 2009, 15, 1188–1197.

- Girard, J.P.; Lehtonen, H.; Caizergues-Ferrer, M.; Amalric, F.; Tollervey, D.; Lapeyre, B. GAR1 Is an Essential Small Nucleolar RNP Protein Required for Pre-RRNA Processing in Yeast. EMBO J. 1992, 11, 673.

- Maiorano, D.; Brimage, L.J.E.; Leroy, D.; Kearsey, S.E. Functional Conservation and Cell Cycle Localization of the Nhp2 Core Component of H + ACA SnoRNPs in Fission and Budding Yeasts. Exp. Cell Res. 1999, 252, 165–174.

- Venteicher, A.S.; Abreu, E.B.; Meng, Z.; McCann, K.E.; Terns, R.M.; Veenstra, T.D.; Terns, M.P.; Artandi, S.E. A Human Telomerase Holoenzyme Protein Required for Cajal Body Localization and Telomere Synthesis. Science 2009, 323, 644–648.

- Freund, A.; Zhong, F.L.; Venteicher, A.S.; Meng, Z.; Veenstra, T.D.; Frydman, J.; Artandi, S.E. Proteostatic Control of Telomerase Function through TRiC-Mediated Folding of TCAB1. Cell 2014, 159, 1389–1403.

- Flint, J.; Craddock, C.F.; Villegas, A.; Bentley, D.P.; Williams, H.J.; Galanello, R.; Cao, A.; Wood, W.G.; Ayyub, H.; Higgs, D.R. Healing of Broken Human Chromosomes by the Addition of Telomeric Repeats. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1994, 55, 505.

- Nergadze, S.G.; Santagostino, M.A.; Salzano, A.; Mondello, C.; Giulotto, E. Contribution of Telomerase RNA Retrotranscription to DNA Double-Strand Break Repair during Mammalian Genome Evolution. Genome Biol. 2007, 8.

- Nandakumar, J.; Cech, T.R. Finding the End: Recruitment of Telomerase to Telomeres. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2013, 14, 69–82.

- Furuya, T.; Morgan, R.; Berger, C.S.; Sandberg, A.A. Presence of Telomeric Sequences on Deleted Chromosomes and Their Absence on Double Minutes in Cell Line HL-60. Cancer Genet. Cytogenet. 1993, 70, 132–135.

- Meltzer, P.S.; Guan, X.Y.; Trent, J.M. Telomere Capture Stabilizes Chromosome Breakage. Nat. Genet. 1993 43 1993, 4, 252–255.

- McClintock, B. The Stability of Broken Ends of Chromosomes in Zea Mays. Genetics 1941, 26, 234.

- Q, F.; M, Y. New Telomere Formation Coupled with Site-Specific Chromosome Breakage in Tetrahymena Thermophila. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1996, 16, 1267–1274.

- Matsumoto, T.; Fukui, K.; Niwa, O.; Sugawara, N.; Szostak, J.W.; Yanagida, M. Identification of Healed Terminal DNA Fragments in Linear Minichromosomes of Schizosaccharomyces Pombe. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1987, 7, 4424–4430.

- Kramer, K.M.; Haber, J.E. New Telomeres in Yeast Are Initiated with a Highly Selected Subset of TG1-3 Repeats. Genes Dev. 1993, 7, 2345–2356.

- Wang, S.S.; Zakian, V.A. Telomere-Telomere Recombination Provides an Express Pathway for Telomere Acquisition. Nature 1990, 345, 456–458.

- Zhang, J.M.; Yadav, T.; Ouyang, J.; Lan, L.; Zou, L. Alternative Lengthening of Telomeres through Two Distinct Break-Induced Replication Pathways. Cell Rep. 2019, 26, 955–968.

- Hong, J.; Lee, J.H.; Chung, I.K. Telomerase Activates Transcription of Cyclin D1 Gene through an Interaction with NOL1. J. Cell Sci. 2016, 129, 1566–1579.