| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Madhu Gupta | -- | 3013 | 2022-12-14 09:41:43 | | | |

| 2 | Jessie Wu | Meta information modification | 3013 | 2022-12-15 06:06:42 | | | | |

| 3 | Jessie Wu | Meta information modification | 3013 | 2022-12-15 06:08:57 | | |

Video Upload Options

A vaccine is created to develop specific immunity against a particular disease or infection. The purpose of cancer immunotherapy is to activate the immune system so that it can identify and eliminate cancer cells. Anticancer immunotherapies are classified as either “passive” or “active” based on their ability to (re-)activate the host immune system against malignant cells. Tumor-targeting monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) and adoptively transferred T-cells (among other approaches) are considered passive forms of immunotherapy because they have intrinsic anticancer activity. Antigen-specificity is an alternative classification of immunotherapeutic anticancer regimens. While tumor-targeting mAbs are widely regarded as antigen-specific interventions, immunostimulatory cytokines or checkpoint blockers activate anticancer immune responses with unknown (and generally broad) specificity.

1. Current Vaccines and Antigens for Cancer Treatment

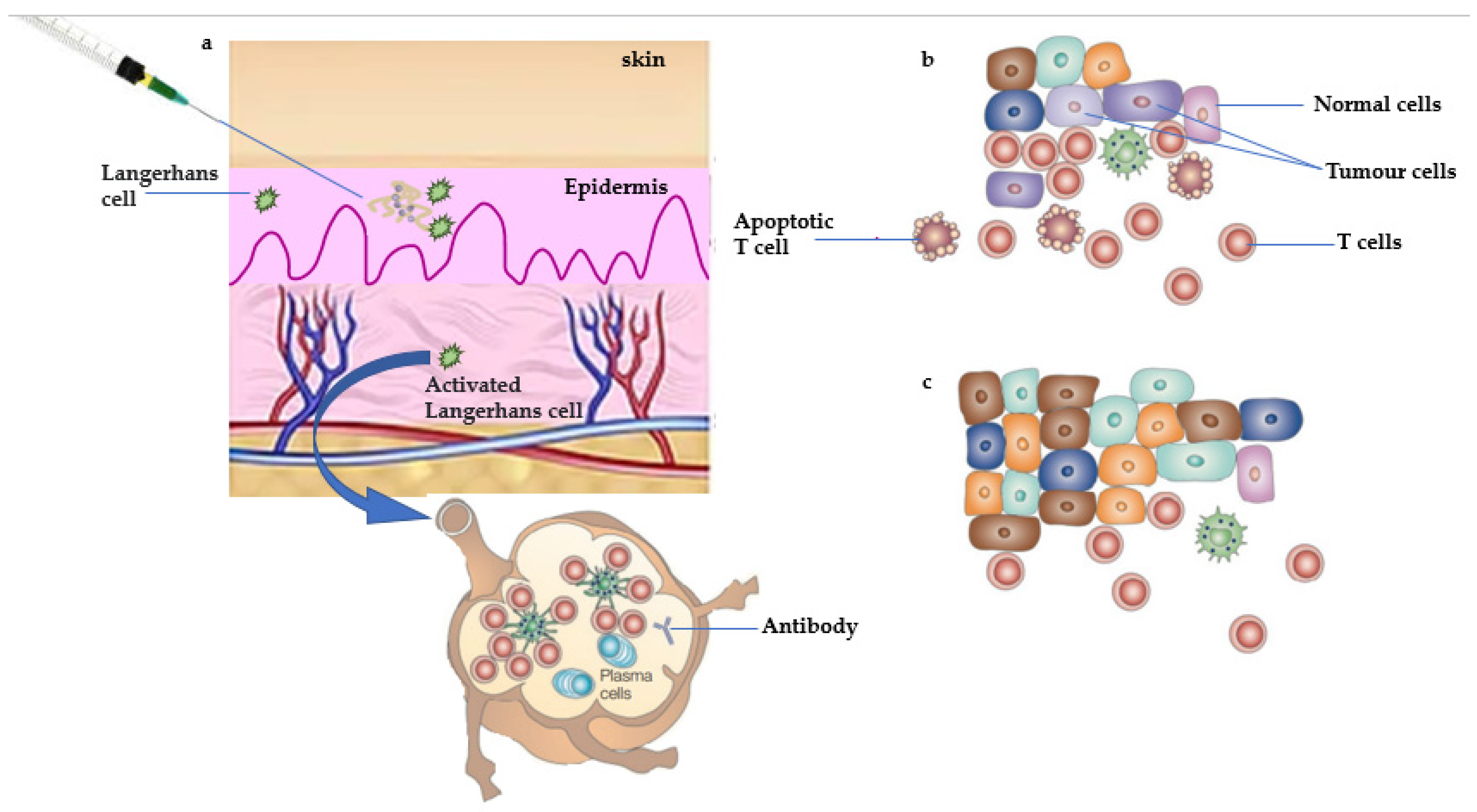

1.1. Antitumor Response of Therapeutic Vaccine

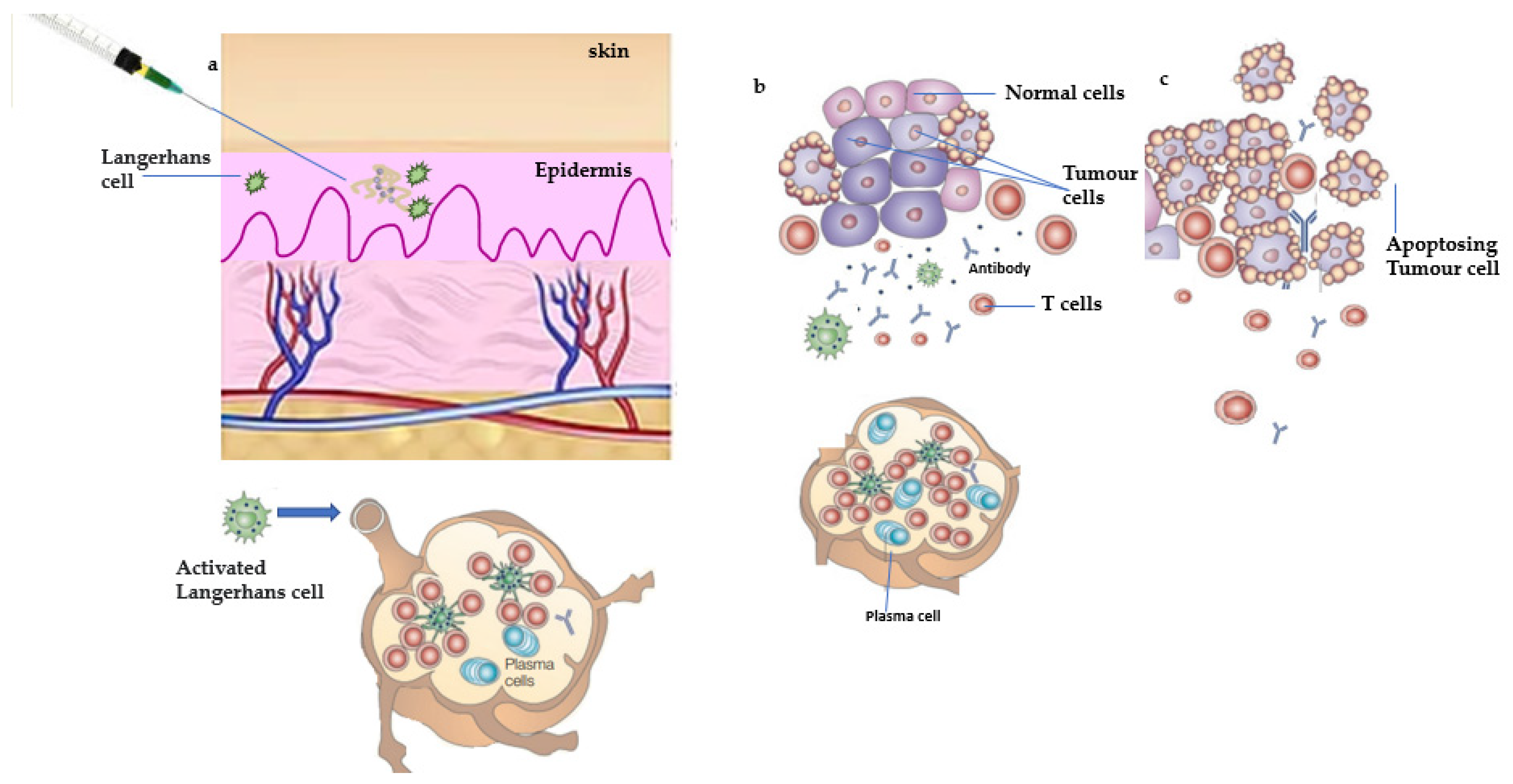

1.2. Antitumor Response of Prophylactic Vaccine

| Name of Vaccine/ Antigens |

Type of Vaccine | Targeted Site | Combination/Route of Administration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Onyvax | Anti-idiotype vaccine | Colorectal adenocarcinoma |

Either intramuscularly with the alum adjuvant or endemic with the BCG vaccine |

| OncoVAX | A personalized vaccination/Autologous vaccine | Stomach cancer | Not in use |

| Cancer VAX | Autologous vaccine | Surgery for the management of patients with stage III melanoma | Along with the BCG vaccine, another vaccine is administered |

| NY-ESO-1 | Peptide vaccine | Stage II to IV cancer displaying the NY-ESO-1, LAGE marker LAGE, or NY-ESO-1 antigens | Endemic |

| 11D10 | Anti-idiotype vaccine | Non-small cell lung cancer in stages II or IIIA (T1-3, N1-2, M0) | Beginning 14 to 45 days following surgery |

| GP100 AND MART-1 | GP100, MART-1, and tyrosinase peptides | Stage III or IV ocular or mucosal melanoma, or stage IIB IIC, III, or IV cutaneous melanoma | In addition to the alum adjuvant |

| ALVAC-CEA/B7.1 | Virus antigens | Metastatic colorectal cancer | Provided together with treatment as soon as a condition is diagnosed |

| VG-1000 Vaccine | Autologous therapy | Carcinomas and melanomas | First-line therapy for people with newly discovered malignancies |

| HSPPC-96, or Oncophage | Antigens extracted from melanoma | Autologous therapy | Heat-shock protein |

| Sipuleucel-T | Dendritic cell vaccine | Metastases castrate-resistant cancer that is silent or barely symptomatic (hormone refractory) breast cancer | Intramuscularly |

| HPV Vaccine • Gardasil |

Human papillomavirus (HPV) | Girl’s and women’s vulvar, vaginal, and cervical cancer | Given intramuscularly in the greater posterolateral portion of the thigh or the deltoid portion of the right forearm |

| Cervarix | Human papillomavirus (HPV) | Types 16 and 18 of the carcinogenic human papillomaviruses (HPV) | Three injections of 0.5 mL each into the muscle |

| Other drugs | |||

| Thalidomide | Multiple myeloma | It is advised to take 200 mg of Thalomid once daily (in 28-day treatment cycles) orally with water, ideally just before bed and at least an hour after dinner. | |

| Lenalidomide | Multiple myeloma | Administered orally | |

| Bacillus Calmette–Guérin |

Bladder cancer in its superficial stages, colon cancer, lung cancer, and melanoma | There are several ways to deliver Bacillus Calmette–Guerin, including intravenously, subcutaneously, directly into some tumors, intranasally, pharyngeally, or as an inhalation spray into the lungs. |

| Paradigm | Example | Approved * | Target |

|---|---|---|---|

| mAbs that target tumors | Herceptin | Yes | Herceptin is approved for the treatment of early-stage breast cancer that is human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive (HER2+). |

| Transfer of adoptive cells | Vemurafenib | No | Vemurafenib is used to slow the growth of certain types of cancer cells. |

| Oncolytic viruses | RIGVIR, Oncorine, and T-VEC | Yes | The treatment, which is injected into tumors, was engineered to produce a protein that stimulates the production of immune cells in the body and to reduce the risk of causing herpes. |

| DC-based therapies | _ | No | Targeted treatment that involves extracting and manipulating components of a patient’s immune system (the dendritic cells) to boost its chances of eliminating unnoticed cancer cells. |

| Vaccinations based on peptides | TAS0314 | Yes | Dramatically suppressed tumor growth. |

| Immunomodulatory mAbs | Rituximab (Rituxan) | Yes | It specifically targets the CD20 protein. B-cells, a type of white blood cell, have CD20, and it is indicated in patients for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia. |

| Immunostimulatory cytokines | IFN-α | Yes | Approved for the treatment of some hematological malignancies and AIDS-related Kaposi sarcoma. |

| Immunosuppressive metabolism inhibitors | Rapamycin | No | Decrease the risk of organ transplant patients to develop cancer. |

| PRR agonists | Imiquimod | Yes | To achieve the purpose of regulating immunity and treating tumors. |

| ICD inducers | Radiation | Yes | The best-characterized inducer of immunogenic cell death. |

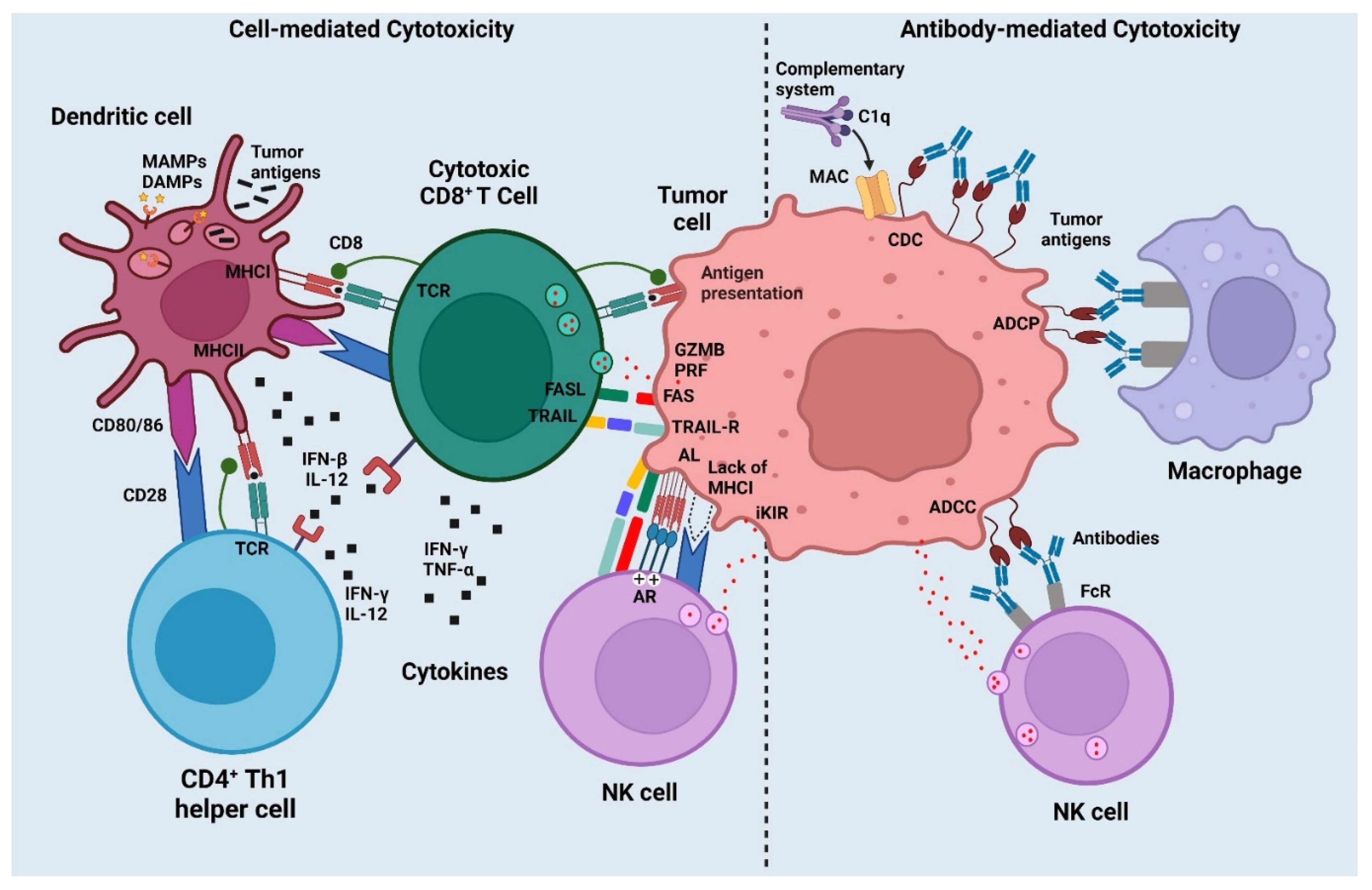

2. Mechanisms of Cancer Vaccines

References

- Mitchell, M.S. Perspective on Allogeneic Melanoma Lysates in Active Specific Immunotherapy. Semin. Oncol. 1998, 25, 623–635.

- Nestle, F.O.; Banchereau, J.; Hart, D. Dendritic Cells: On the Move from Bench to Bedside. Nat. Med. 2001, 7, 761–765.

- Celluzzi, C.M.; Falo, L.D.J. Physical Interaction between Dendritic Cells and Tumor Cells Results in an Immunogen That Induces Protective and Therapeutic Tumor Rejection. J. Immunol. 1998, 160, 3081–3085.

- Nouri-Shirazi, M.; Banchereau, J.; Bell, D.; Burkeholder, S.; Kraus, E.T.; Davoust, J.; Palucka, K.A. Dendritic Cells Capture Killed Tumor Cells and Present Their Antigens to Elicit Tumor-Specific Immune Responses. J. Immunol. 2000, 165, 3797–3803.

- Chang, A.E.; Redman, B.G.; Whitfield, J.R.; Nickoloff, B.J.; Braun, T.M.; Lee, P.P.; Geiger, J.D.; Mulé, J.J. A Phase I Trial of Tumor Lysate-Pulsed Dendritic Cells in the Treatment of Advanced Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2002, 8, 1021–1032.

- Heiser, A.; Maurice, M.A.; Yancey, D.R.; Wu, N.Z.; Dahm, P.; Pruitt, S.K.; Boczkowski, D.; Nair, S.K.; Ballo, M.S.; Gilboa, E.; et al. Induction of Polyclonal Prostate Cancer-Specific CTL Using Dendritic Cells Transfected with Amplified Tumor RNA. J. Immunol. 2001, 166, 2953–2960.

- Nair, S.K.; Morse, M.; Boczkowski, D.; Cumming, R.I.; Vasovic, L.; Gilboa, E.; Lyerly, H.K. Induction of Tumor-Specific Cytotoxic T Lymphocytes in Cancer Patients by Autologous Tumor RNA-Transfected Dendritic Cells. Ann. Surg. 2002, 235, 540–549.

- Condon, C.; Watkins, S.C.; Celluzzi, C.M.; Thompson, K.; Falo, L.D.J. DNA-Based Immunization by In Vivo Transfection of Dendritic Cells. Nat. Med. 1996, 2, 1122–1128.

- Whiteside, T.L.; Gambotto, A.; Albers, A.; Stanson, J.; Cohen, E.P. Human Tumor-Derived Genomic DNA Transduced into a Recipient Cell Induces Tumor-Specific Immune Responses Ex Vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 9415–9420.

- Heiser, A.; Coleman, D.; Dannull, J.; Yancey, D.; Maurice, M.A.; Lallas, C.D.; Dahm, P.; Niedzwiecki, D.; Gilboa, E.; Vieweg, J. Autologous Dendritic Cells Transfected with Prostate-Specific Antigen RNA Stimulate CTL Responses against Metastatic Prostate Tumors. J. Clin. Investig. 2002, 109, 409–417.

- Tsung, K.; Norton, J.A. In Situ Vaccine, Immunological Memory and Cancer Cure. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2016, 12, 117–119.

- Pulendran, B.; Ahmed, R. Immunological Mechanisms of Vaccination. Nat. Immunol. 2011, 12, 509–517.

- Chang, M.-H.; You, S.-L.; Chen, C.-J.; Liu, C.-J.; Lee, C.-M.; Lin, S.-M.; Chu, H.-C.; Wu, T.-C.; Yang, S.-S.; Kuo, H.-S.; et al. Decreased Incidence of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Hepatitis B Vaccinees: A 20-Year Follow-up Study. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2009, 101, 1348–1355.

- Zhou, F.; Leggatt, G.R.; Frazer, I.H. Human Papillomavirus 16 E7 Protein Inhibits Interferon-γ-Mediated Enhancement of Keratinocyte Antigen Processing and T-Cell Lysis. FEBS J. 2011, 278, 955–963.

- Frazer, I.H.; Levin, M.J. Paradigm Shifting Vaccines: Prophylactic Vaccines against Latent Varicella-Zoster Virus Infection and against HPV-Associated Cancer. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2011, 1, 268–279.

- Joura, E.A.; Giuliano, A.R.; Iversen, O.-E.; Bouchard, C.; Mao, C.; Mehlsen, J.; Moreira, E.D.; Ngan, Y.; Petersen, L.K.; Lazcano-Ponce, E.; et al. A 9-Valent HPV Vaccine against Infection and Intraepithelial Neoplasia in Women. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 711–723.

- Cramer, D.W.; Titus-Ernstoff, L.; McKolanis, J.R.; Welch, W.R.; Vitonis, A.F.; Berkowitz, R.S.; Finn, O.J. Conditions Associated with Antibodies against the Tumor-Associated Antigen MUC1 and Their Relationship to Risk for Ovarian Cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. Publ. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. Am. Soc. Prev. Oncol. 2005, 14, 1125–1131.

- Jiang, T.; Shi, T.; Zhang, H.; Hu, J.; Song, Y.; Wei, J.; Ren, S.; Zhou, C. Tumor Neoantigens: From Basic Research to Clinical Applications. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2019, 12, 93.

- Amanna, I.J.; Slifka, M.K. Contributions of Humoral and Cellular Immunity to Vaccine-Induced Protection in Humans. Virology 2011, 411, 206–215.

- Zhang, R.; Billingsley, M.M.; Mitchell, M.J. Biomaterials for Vaccine-Based Cancer Immunotherapy. J. Control. Release 2018, 292, 256–276.

- Crews, D.W.; Dombroski, J.A.; King, M.R. Prophylactic Cancer Vaccines Engineered to Elicit Specific Adaptive Immune Response. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 626463.

- Yutani, S.; Shirahama, T.; Muroya, D.; Matsueda, S.; Yamaguchi, R.; Morita, M.; Shichijo, S.; Yamada, A.; Sasada, T.; Itoh, K. Feasibility Study of Personalized Peptide Vaccination for Hepatocellular Carcinoma Patients Refractory to Locoregional Therapies. Cancer Sci. 2017, 108, 1732–1738.

- Galluzzi, L.; Vacchelli, E.; Bravo-San Pedro, J.-M.; Buqué, A.; Senovilla, L.; Baracco, E.E.; Bloy, N.; Castoldi, F.; Abastado, J.-P.; Agostinis, P.; et al. Classification of Current Anticancer Immunotherapies. Oncotarget 2014, 5, 12472–12508.

- Chen, D.S.; Mellman, I. Elements of Cancer Immunity and the Cancer-Immune Set Point. Nature 2017, 541, 321–330.

- Hanoteau, A.; Moser, M. Chemotherapy and Immunotherapy: A Close Interplay to Fight Cancer? Oncoimmunology 2016, 5, e1190061.

- Yamazaki, T.; Galluzzi, L. Blinatumomab Bridges the Gap between Leukemia and Immunity. Oncoimmunology 2017, 6, e1358335.

- Mahoney, K.M.; Rennert, P.D.; Freeman, G.J. Combination Cancer Immunotherapy and New Immunomodulatory Targets. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2015, 14, 561–584.

- Garg, A.D.; More, S.; Rufo, N.; Mece, O.; Sassano, M.L.; Agostinis, P.; Zitvogel, L.; Kroemer, G.; Galluzzi, L. Trial Watch: Immunogenic Cell Death Induction by Anticancer Chemotherapeutics. Oncoimmunology 2017, 6, e1386829.

- Steinman, R.M.; Cohn, Z.A. Identification of a Novel Cell Type in Peripheral Lymphoid Organs of Mice. I. Morphology, Quantitation, Tissue Distribution. J. Exp. Med. 1973, 137, 1142–1162.

- Merad, M.; Sathe, P.; Helft, J.; Miller, J.; Mortha, A. The Dendritic Cell Lineage: Ontogeny and Function of Dendritic Cells and Their Subsets in the Steady State and the Inflamed Setting. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2013, 31, 563–604.

- Aruga, A. Vaccination of Biliary Tract Cancer Patients with Four Peptides Derived from Cancer-Testis Antigens. Oncoimmunology 2013, 2, e24882.

- Ricupito, A.; Grioni, M.; Calcinotto, A.; Bellone, M. Boosting Anticancer Vaccines: Too Much of a Good Thing? Oncoimmunology 2013, 2, e25032.

- Schnurr, M.; Duewell, P. Breaking Tumor-Induced Immunosuppression with 5’-Triphosphate SiRNA Silencing TGFβ and Activating RIG-I. Oncoimmunology 2013, 2, e24170.

- Adler, A.J.; Vella, A.T. Betting on Improved Cancer Immunotherapy by Doubling down on CD134 and CD137 Co-Stimulation. Oncoimmunology 2013, 2, e22837.

- Conlon, K.C.; Miljkovic, M.D.; Waldmann, T.A. Cytokines in the Treatment of Cancer. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2019, 39, 6–21.

- Humphries, C. Adoptive Cell Therapy: Honing That Killer Instinct. Nature 2013, 504, S13–S15.

- Hailemichael, Y.; Overwijk, W.W. Peptide-Based Anticancer Vaccines: The Making and Unmaking of a T-Cell Graveyard. Oncoimmunology 2013, 2, e24743.

- Bijker, M.S.; Melief, C.J.M.; Offringa, R.; van der Burg, S.H. Design and Development of Synthetic Peptide Vaccines: Past, Present and Future. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2007, 6, 591–603.

- Yaddanapudi, K.; Mitchell, R.A.; Eaton, J.W. Cancer Vaccines: Looking to the Future. Oncoimmunology 2013, 2, e23403.

- Valmori, D.; Souleimanian, N.E.; Tosello, V.; Bhardwaj, N.; Adams, S.; O’Neill, D.; Pavlick, A.; Escalon, J.B.; Cruz, C.M.; Angiulli, A.; et al. Vaccination with NY-ESO-1 Protein and CpG in Montanide Induces Integrated Antibody/Th1 Responses and CD8 T Cells through Cross-Priming. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 8947–8952.

- Donninger, H.; Li, C.; Eaton, J.; Yaddanapudi, K. Cancer Vaccines: Promising Therapeutics or an Unattainable Dream. Vaccines 2021, 9, 668.

- Paston, S.J.; Brentville, V.A.; Symonds, P.; Durrant, L.G. Cancer Vaccines, Adjuvants, and Delivery Systems. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 627932.

- Mehlen, P.; Puisieux, A. Metastasis: A Question of Life or Death. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2006, 6, 449–458.

- Farhood, B.; Najafi, M.; Mortezaee, K. CD8(+) Cytotoxic T Lymphocytes in Cancer Immunotherapy: A Review. J. Cell Physiol. 2019, 234, 8509–8521.

- Locy, H. Dendritic Cells: The Tools for Cancer Treatment; Melhaoui, S., Ed.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2018; p. 6. ISBN 978-1-78984-417-7.

- Laidlaw, B.J.; Craft, J.E.; Kaech, S.M. The Multifaceted Role of CD4(+)T Cells in CD8(+) T Cell Memory. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16, 102–111.

- Thorsson, V.; Gibbs, D.L.; Brown, S.D.; Wolf, D.; Bortone, D.S.; Ou Yang, T.-H.; Porta-Pardo, E.; Gao, G.F.; Plaisier, C.L.; Eddy, J.A.; et al. The Immune Landscape of Cancer. Immunity 2018, 48, 812–830.e14.

- Bhat, P.; Leggatt, G.; Waterhouse, N.; Frazer, I.H. Interferon-γ Derived from Cytotoxic Lymphocytes Directly Enhances Their Motility and Cytotoxicity. Cell Death Dis. 2017, 8, e2836.

- Chen, C.; Gao, F.-H. Th17 Cells Paradoxical Roles in Melanoma and Potential Application in Immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 187.

- Zahavi, D.; AlDeghaither, D.; O’Connell, A.; Weiner, L.M. Enhancing Antibody-Dependent Cell-Mediated Cytotoxicity: A Strategy for Improving Antibody-Based Immunotherapy. Antib. Ther. 2018, 1, 7–12.

- Almagro, J.C.; Daniels-Wells, T.R.; Perez-Tapia, S.M.; Penichet, M.L. Progress and Challenges in the Design and Clinical Development of Antibodies for Cancer Therapy. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 1751.

- Huijbers, E.J.M.; Griffioen, A.W. The Revival of Cancer Vaccines—The Eminent Need to Activate Humoral Immunity. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2017, 13, 1112–1114.

- Tarek, M.M.; Shafei, A.E.; Ali, M.A.; Mansour, M.M. Computational Prediction of Vaccine Potential Epitopes and 3-Dimensional Structure of XAGE-1b for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Immunotherapy. Biomed. J. 2018, 41, 118–128.

- Souza-Fonseca-Guimaraes, F.; Cursons, J.; Huntington, N.D. The Emergence of Natural Killer Cells as a Major Target in Cancer Immunotherapy. Trends Immunol. 2019, 40, 142–158.

- Cerundolo, V.; Silk, J.D.; Masri, S.H.; Salio, M. Harnessing Invariant NKT Cells in Vaccination Strategies. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2009, 9, 28–38.