Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Marcel P Goldschen-Ohm | -- | 2107 | 2022-12-13 17:45:37 | | | |

| 2 | Beatrix Zheng | + 249 word(s) | 2356 | 2022-12-15 08:08:32 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Goldschen-Ohm, M.P. Benzodiazepine Modulation of GABAA Receptors. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/38712 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Goldschen-Ohm MP. Benzodiazepine Modulation of GABAA Receptors. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/38712. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Goldschen-Ohm, Marcel P.. "Benzodiazepine Modulation of GABAA Receptors" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/38712 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Goldschen-Ohm, M.P. (2022, December 13). Benzodiazepine Modulation of GABAA Receptors. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/38712

Goldschen-Ohm, Marcel P.. "Benzodiazepine Modulation of GABAA Receptors." Encyclopedia. Web. 13 December, 2022.

Copy Citation

Benzodiazepines (BZDs) are a class of widely prescribed psychotropic drugs that target GABAA receptors (GABAARs) to tune inhibitory synaptic signaling throughout the central nervous system. Despite knowing their molecular target, the researchers still do not fully understand the mechanism of modulation at the level of the channel protein. Nonetheless, functional studies, together with cryo-EM structures of GABAA(α1)2(βX)2(γ2)1 receptors in complex with BZDs, provide a wealth of information to aid in addressing this gap in knowledge.

benzodiazepines

GABAA receptor

structural mechanism

1. BZD Modulation of GABA Binding

Benzodiazepine (BZD) binding to the classical extracellular domain (ECD) site does not, by itself, result in any appreciable opening of closed channels but rather modulates the ability of agonists such as GABA to evoke pore opening. The enhanced GABAergic inhibition conferred by BZD PAMs largely stems from their potentiation and prolongation of GABAAR postsynaptic currents [1][2][3]. Strikingly, potentiation of current responses by BZDs occurs only for activation by subsaturating but not saturating concentrations of GABA, resulting in a leftward shift of the GABA concentration–response relation. This suggests that the mechanism underlying this potentiation involves enhancement of GABA binding [4][5][6][7][8]. At lower subsaturating GABA concentrations, where not all sites are occupied, enhanced GABA binding effectively results in larger current responses equivalent to those elicited by a higher concentration of GABA. In contrast, at saturating GABA concentrations, where all sites are already occupied, enhanced binding has no further effect. Slower GABA unbinding due to the stabilization of the bound complex can also explain the prolongation of the current decay by BZDs. Consistent with this idea, DZ has been shown to primarily affect the frequency of channel opening, which depends on the rate of GABA binding, whereas DZ has little effect on the duration of each opening event, which is governed by the energetics of pore closure downstream from the initial binding events (but see [6] as well as [4][9]).

For an effect on GABA binding, crosstalk between GABA and BZD sites is required. The enhanced binding of radiolabeled DZ in the presence of GABA in brain membranes supports the idea that agonists and BZD PAMs are costabilizing [10][11]. Observations of the rate of modification by methanethiosulfonate (MTS) reagents of introduced cysteines in GABA or BZD ECD sites indicate that binding at either the GABA or BZD sites induces distinct structural changes at the other site [12][13]. The dependence of these changes on the nature of the bound ligand (agonist or PAM, antagonist, or inverse agonist or NAM) suggests that these motions are relevant to the action of the ligand and indicate that GABA increases the aqueous accessibility to the BZD binding pocket.

For all ligand-gated ion channels, ligands that open the channel (agonists) bind more tightly to open (conducting) versus closed (non-conducting) channel conformations. Thus, any perturbation (e.g., BZD binding) that increases the probability of a channel to adopt an open conformation will necessarily increase the receptor’s apparent affinity for GABA, even if it has no effect on the affinities for each distinct closed and open state. Indeed, this can severely complicate the interpretation of equilibrium binding measurements [14][15]. Although BZDs clearly induce shifts in the apparent affinity for GABA, it is not yet fully understood to what degree this reflects direct changes in binding affinities vs. shifts in the closed–open equilibrium.

2. BZD Modulation of Pore Gating

Although some single-channel observations are consistent with the idea that BZDs primarily modulate GABA binding [6], other studies observed changes in macroscopic desensitization or single-channel open durations that are inconsistent with effects solely on agonist binding [9][16][17]. In addition, two lines of evidence strongly indicate that BZDs alter channel gating steps downstream of GABA binding. First, peak current responses to saturating concentrations of partial agonists are potentiated by BZDs [18][19][20][21]. Partial agonists bind at the GABA sites but elicit smaller current responses than full agonists such as GABA. Nonetheless, at saturating concentrations the sites are fully occupied, and thus the increased maximal current response conferred by BZDs must reflect the modulation of gating conformational changes in the partial agonist-bound receptor, regardless of any effects on the binding step itself.

Second, BZDs directly gate mutant receptors in the absence of GABA [18][19][20][21][22]. A mutation in the pore gate confers a channel that spontaneously exchanges between closed and open conformations [23][24]. The closed–open equilibrium of such spontaneously active mutants is modulated by BZDs alone, an effect that necessarily does not involve the binding of agonists such as GABA. Although these observations require mutating the receptor in such a way as to significantly alter the resting equilibrium, it is likely that the mutant still gates by the same mechanism as wild-type channels. In support of this idea, a single-channel analysis of mutants and combinations thereof that confer such spontaneous unliganded gating in homologous nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) showed that these mutants alter the closed–open equilibrium independent of agonist-elicited gating [25]. This suggests that the chemical energy from BZD binding does affect the pore gate, but the amount of energy is insufficient to elicit appreciable channel opening without additional energy from either agonist binding or another perturbation, such as a mutation.

3. BZD Modulation of Closed-Channel Pre-Activation

Single-channel gating dynamics for full versus partial agonists at homologous nAChR and glycine receptors (GlyRs) can be rationalized by a mechanism whereby agonist binding is associated with the receptor adopting a “flipped” or “primed” pre-active conformation that precedes pore opening [26][27][28][29]. This model discriminates between partial and full agonists based on their ability to bias the receptor towards this pre-active intermediate state, following which pore opening/closing is ligand-independent.

Strikingly, if one assumes that BZDs influence a similar “flipping” or “priming” pre-activation step in GABAARs [30], apparently conflicting observations supporting BZD-modulation of either agonist affinity or pore gating can both be readily explained [31][32][33]. By modulating the probability of receptor pre-activation, BZDs regulate the amount of time spent in a state from which the channel can open. Under conditions where pre-activation is not highly probable, enhanced pre-activation by BZDs will increase the frequency of channel opening. This explains the observed BZD-potentiation of currents evoked with either partial agonists or subsaturating GABA concentrations where only one of the two agonist sites are occupied. Conversely, in saturating GABA with both sites occupied, the channel is already so strongly biased towards its pre-active state that a further enhancement of pre-activation by BZDs has little to no additional effect on channel opening. This explains the lack of potentiation of currents evoked by saturating GABA. A similar mechanism can explain the modulation by non-BZDs such as the Z-drug zolpidem, which binds at the canonical BZD site [34].

Given its explanatory power, it is highly plausible that such a mechanism underlies many of the observed effects of BZD binding in the ECD. Nonetheless, direct evidence for this mechanism in GABAARs is lacking. In GlyRs and nAChRs, the pre-active state preceding pore opening is very short-lived, and a similarly transient non-conducting intermediate in GABAARs challenges both functional and structural observations. Moreover, observations that single-channel open durations are altered by partial versus full agonists or BZDs are not explained by changes in pre-activation alone, which only affect the opening frequency [9][35]. Some of these complications may reflect BZD binding to TMD sites, which based on their proximity, could directly affect the pore gate. Otherwise, the totality of the effects of BZDs at the canonical ECD site is at least a bit more complex than the satisfyingly simple approximation that they modulate channel pre-activation.

4. Structural Mechanism for BZD Modulation in the ECD

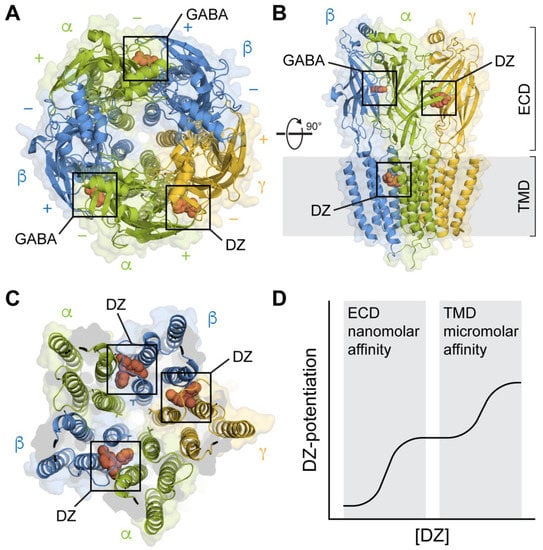

Advances in cryo-EM have begun to provide structural snapshots of heteromeric GABAA(α1)2(βX)2(γ2)1 receptors in complex with both agonists and BZDs [36][37][38][39][40][41][42]. These studies validate the canonical high-affinity BZD site in the ECD, as identified by functional studies, and reveal details as well as subunit specificity of lower-affinity BZD sites in the TMD (Figure 1A–C). Together with structures of homologous pentameric ligand-gated ion channels (pLGICs) such as nAChRs, GlyRs, 5-HT3 receptors, and prokaryotic homologues [43], these structural snapshots are generally in agreement with the overall gross subunit motions occurring during agonist gating. A comparison of agonist-bound structures with either unliganded or antagonist-bound structures indicate that agonist binding is associated with the ECDs adopting a more compact conformation with an increase in the buried surface area at the intersubunit interfaces and loop C moving inward over the agonist. In addition, the ECD of each subunit undergoes a rotation and tilt that results in an expansion at the ECD/TMD interface, where the M2-M3 linkers move radially outward and the top of the pore-lining M2 helices splay apart, resulting in the opening of the hydrophobic 9′ leucine ring near their center, which constitutes the activation gate.

Figure 1. Structures of synaptic GABAARs in complex with the BZD PAM diazepam (DZ) at both high-affinity ECD and lower-affinity TMD sites. (A) Top-down view with GABA bound at the β+/α− interfaces and DZ bound at the α+/γ− interface in the ECD. Cryo-EM map of GABAA(α1)2(β3)2(γ2)1 from PDB 6HUP. (B) Side view of the structure in A, additionally showing one of several binding sites for DZ in the TMD. Only three subunits are shown for clarity. (C) Same perspective as in (A) for a slice through the TMD. Cryo-EM map of GABAA(α1)2(β2)2(γ2)1 from PDB 6X3X. Three binding sites for DZ are highlighted at the β+/α− and γ+/β− intersubunit pockets between the TM helices and below the M2-M3 linker of one of the subunits. The central pore-gate-forming 9′ leucine residues are shown as sticks near the middle of the pore-lining M2 helices. (D) Biphasic modulation by DZ at the canonical high-affinity site in the ECD and lower-affinity sites in the TMD.

Comparisons of the structures of GABAA(α1)2(β2–3)2(γ2)1 receptors with and without classical BZDs such as DZ show, at most, only subtle conformational differences in the ECD [38][39][40][44]. Based on this observation, Masiulis et al. suggested that BZD PAMs act at their high-affinity site to stabilize the α+/γ− subunit interface, which they proposed should aid in the global compaction of the ECD during gating and thereby promote channel opening [39]. In contrast to PAMs, occupation of the α+/γ− ECD site by the BZD antagonist flumazenil confers a slight expansion in the ECD [44].

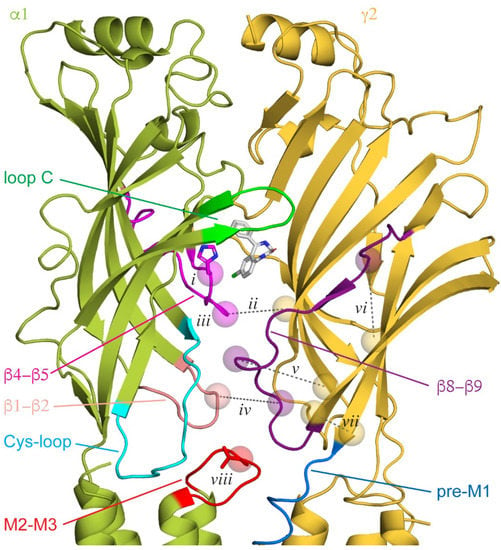

Consistent with the idea that the stability of the α+/γ− subunit interface is important for BZD modulation, cysteine cross-linking between α and γ subunits in close proximity to the critical histidine residue at the back of the canonical BZD site in the α subunit β4–β5 linker mimics the action of BZDs and is reversible upon breaking the disulfide bond [45] (Figure 2ii). In contrast, the insertions of glycine residues to increase the flexibility of β4–β5 linkers in the α, β, or γ subunits all impair the BZD potentiation of GABA-evoked currents [46] (Figure 2iii). The importance of the linker in all subunits suggests that BZDs are associated with global changes that could couple BZD and agonist binding sites via interactions between the β4–β5 linker at the back of each binding site and the neighboring subunit beta barrel. Indeed, mutations affecting BZD modulation are not localized to a specific domain, supporting the notion of a more global effect on the channel conformation.

Figure 2. Canonical ECD binding α+/γ− interface, with diazepam (DZ) shown as white sticks bound behind loop C. Other loops implicated in binding or intersubunit interactions are indicated. Cryo-EM map for GABAA(α1)2(β3)2(γ2)1 from PDB 6HUP. Features discussed in the main text are indicated with spheres for residue Cα atoms and dashed lines for cross-linked residue pairs (numbered labels are referenced in the main text). The critical histidine residue in the β4−β5 loop within the BZD binding pocket (i) and the central valine residue in the α1 M2-M3 linker (viii) are shown as sticks.

Given the rigid body movement of the subunit ECD beta barrels, it is natural to expect much of the dynamics to occur at the interfaces between subunits, which include the GABA and BZD binding sites [47]. Only one of the two GABA sites shares the same α subunit as the BZD site, raising the possibility that BZDs may induce local changes that preferentially modulate activation via a single GABA site. However, the serial disruption of each of the two GABA binding sites in concatenated receptors revealed that BZDs can modulate currents in response to GABA binding at either site [48]. Apart from BZD- and agonist-binding α+/γ− and β+/α− interfaces, respectively, epilepsy-related mutations that disrupt electrostatic interactions at the canonical nonbinding γ+/β− interface reduce the stability of the BZD-receptor complex [49]. Thus, the destabilization (or stabilization) of one interface results in a more global destabilization (or stabilization) at other interfaces, consistent with the idea that BZDs influence the stability of intersubunit contacts throughout the ECD.

Although it is likely that BZDs stabilize the α+/γ− interface, it is important to note that all structures of BZD-bound GABAA(α1)2(β2–3)2(γ2)1 receptors to date were obtained with both agonist sites occupied by GABA. Indeed, the inability of BZDs to potentiate currents evoked by saturating GABA is hypothesized to reflect a nearly complete biasing of the receptor to a pre-active conformation by the relatively larger energetic contribution from both bound agonists that effectively overshadows the much smaller contribution from BZD binding in the ECD. Thus, it is perhaps not surprising that little to no BZD-associated motions of the ECD were detected in this condition. Structures of BZD complexes with zero or one bound agonist or with partial agonists that may better inform on the motions associated with BZD binding are currently lacking.

Structural models of homologous GlyR and ACh binding protein in complex with partial agonists suggest that the initial pre-activation step involves loop C swinging towards the bound agonist to adopt a more compact conformation [50][51]. Although the styrene maleic acid (SMA) copolymer used to solubilize GlyR in this research likely biased the conformations to some extent, this bias may have serendipitously aided the observation of a normally transient pre-active state. Taken together with the structures of GABAA(α1)2(βX)2(γ2)1 receptors, this suggests a hypothetical mechanism for BZD modulation via the canonical high-affinity site: BZD PAMs promote the adoption of a pre-activated more compact ECD conformation with loop C closed more tightly around the binding pocket by stabilizing or increasing global intersubunit interactions. It is straightforward to assume that NAMs might have an opposite effect by destabilizing intersubunit interfaces. Consistent with this idea, GABAA(α1)2(β2)2(γ2)1 receptor structures in complex with either a BZD antagonist or NAM exhibit a less compact ECD than complexes with PAMs [40][42].

References

- Möhler, H.; Fritschy, J.-M.; Rudolph, U. A New Benzodiazepine Pharmacology. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2002, 300, 2–8.

- Mozrzymas, J.; Wójtowicz, T.; Piast, M.; Lebida, K.; Wyrembek, P.; Mercik, K. GABA transient sets the susceptibility of mIPSCs to modulation by benzodiazepine receptor agonists in rat hippocampal neurons. J. Physiol. 2007, 585, 29–46.

- Karayannis, T.; Elfant, D.; Huerta-Ocampo, I.; Teki, S.; Scott, R.S.; Rusakov, D.A.; Jones, M.V.; Capogna, M. Slow GABA Transient and Receptor Desensitization Shape Synaptic Responses Evoked by Hippocampal Neurogliaform Cells. J. Neurosci. 2010, 30, 9898–9909.

- Twyman, R.E.; Rogers, C.J.; Macdonald, R.L. Differential regulation of γ-aminobutyric acid receptor channels by diazepam and phenobarbital. Ann. Neurol. 1989, 25, 213–220.

- Lavoie, A.; Twyman, R. Direct Evidence For Diazepam Modulation of GABAA Receptor Microscopic Affinity. Neuropharmacology 1996, 35, 1383–1392.

- Rogers, C.J.; Twyman, R.E.; Macdonald, R.L. Benzodiazepine and beta-carboline regulation of single GABAA receptor channels of mouse spinal neurones in culture. J. Physiol. 1994, 475, 69–82.

- Perrais, D.; Ropert, N. Effect of zolpidem on miniature IPSCs and occupancy of postsynaptic GABAA receptors in central synapses. J. Neurosci. 1999, 19, 578–588.

- Vicini, S.; Mienville, J.M.; Costa, E. Actions of benzodiazepine and beta-carboline derivatives on gamma-aminobutyric acid-activated Cl- channels recorded from membrane patches of neonatal rat cortical neurons in culture. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1987, 243, 1195–1201.

- Li, M.P.; Eaton, M.M.M.; Steinbach, J.H.; Akk, G. The Benzodiazepine Diazepam Potentiates Responses of α1β2γ2L γ-Aminobutyric Acid Type A Receptors Activated by either γ-Aminobutyric Acid or Allosteric Agonists. Anesthesiology 2013, 118, 1417–1425.

- Tallman, J.F.; Thomas, J.W.; Gallager, D.W. GABAergic modulation of benzodiazepine binding site sensitivity. Nature 1978, 274, 383–385.

- Karobath, M.; Sperk, G. Stimulation of benzodiazepine receptor binding by gamma-aminobutyric acid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1979, 76, 1004–1006.

- Sharkey, L.M.; Czajkowski, C. Individually Monitoring Ligand-Induced Changes in the Structure of the GABAA Receptor at Benzodiazepine Binding Site and Non-Binding-Site Interfaces. Mol. Pharmacol. 2008, 74, 203–212.

- Sancar, F.; Czajkowski, C. Allosteric modulators induce distinct movements at the GABA-binding site interface of the GABA-A receptor. Neuropharmacology 2011, 60, 520–528.

- Middendorf, T.R.; Goldschen-Ohm, M.P. The surprising difficulty of “simple” equilibrium binding measurements on ligand-gated ion channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 2022, 154, e202213177.

- Middendorf, T.R.; Aldrich, R.W. Structural identifiability of equilibrium ligand-binding parameters. J. Gen. Physiol. 2016, 149, 105–119.

- Mellor, J.R.; Randall, A.D. Frequency-Dependent Actions of Benzodiazepines on GABAA Receptors in Cultured Murine Cerebellar Granule Cells. J. Physiol. 1997, 503, 353–369.

- Mercik, K.; Piast, M.; Mozrzymas, J. Benzodiazepine receptor agonists affect both binding and gating of recombinant α1β2γ2 gamma-aminobutyric acid-A receptors. NeuroReport 2007, 18, 781–785.

- Rüsch, D.; Forman, S.A. Classic Benzodiazepines Modulate the Open–Close Equilibrium in α1β2γ2Lγ-Aminobutyric Acid Type A Receptors. Anesthesiology 2005, 102, 783–792.

- Campo-Soria, C.; Chang, Y.; Weiss, D.S. Mechanism of action of benzodiazepines on GABAA receptors. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2006, 148, 984–990.

- Downing, S.S.; Lee, Y.T.; Farb, D.H.; Gibbs, T.T. Benzodiazepine modulation of partial agonist efficacy and spontaneously active GABAA receptors supports an allosteric model of modulation. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2005, 145, 894–906.

- Findlay, G.S.; Ueno, S.; Harrison, N.L.; Harris, R. Allosteric modulation in spontaneously active mutant γ-aminobutyric acidA receptors. Neurosci. Lett. 2001, 305, 77–80.

- Nors, J.W.; Gupta, S.; Goldschen-Ohm, M.P. A critical residue in the α1M2–M3 linker regulating mammalian GABAA receptor pore gating by diazepam. eLife 2021, 10, 64400.

- Chang, Y.; Weiss, D.S. Allosteric Activation Mechanism of the α1β2γ2 γ-Aminobutyric Acid Type A Receptor Revealed by Mutation of the Conserved M2 Leucine. Biophys. J. 1999, 77, 2542–2551.

- Scheller, M.; Forman, S.A. Coupled and uncoupled gating and desensitization effects by pore domain mutations in GABA(A) receptors. J. Neurosci. 2002, 22, 8411–8421.

- Purohit, P.; Auerbach, A. Unliganded gating of acetylcholine receptor channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 115–120.

- Lape, R.; Colquhoun, D.; Sivilotti, L.G. On the nature of partial agonism in the nicotinic receptor superfamily. Nature 2008, 454, 722–727.

- Colquhoun, D.; Lape, R. Perspectives on: Conformational coupling in ion channels: Allosteric coupling in ligand-gated ion channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 2012, 140, 599–612.

- Jadey, S.; Auerbach, A. An integrated catch-and-hold mechanism activates nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J. Gen. Physiol. 2012, 140, 17–28.

- Mukhtasimova, N.; Dacosta, C.J.; Sine, S.M. Improved resolution of single channel dwell times reveals mechanisms of binding, priming, and gating in muscle AChR. J. Gen. Physiol. 2016, 148, 43–63.

- Szczot, M.; Kisiel, M.; Czyzewska, M.M.; Mozrzymas, J.W. α1F64 Residue at GABAA Receptor Binding Site Is Involved in Gating by Influencing the Receptor Flipping Transitions. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 3193–3209.

- Gielen, M.C.; Lumb, M.J.; Smart, T.G. Benzodiazepines Modulate GABAA Receptors by Regulating the Preactivation Step after GABA Binding. J. Neurosci. 2012, 32, 5707–5715.

- Goldschen-Ohm, M.P.; Haroldson, A.; Jones, M.V.; Pearce, R.A. A nonequilibrium binary elements-based kinetic model for benzodiazepine regulation of GABAA receptors. J. Gen. Physiol. 2014, 144, 27–39.

- Jatczak-Śliwa, M.; Terejko, K.; Brodzki, M.; Michalowski, M.A.; Czyzewska, M.M.; Nowicka, J.M.; Andrzejczak, A.; Srinivasan, R.; Mozrzymas, J.W. Distinct Modulation of Spontaneous and GABA-Evoked Gating by Flurazepam Shapes Cross-Talk Between Agonist-Free and Liganded GABAA Receptor Activity. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 237.

- Dixon, C.L.; Harrison, N.L.; Lynch, J.W.; Keramidas, A. Zolpidem and eszopiclone prime α1β2γ2 GABAA receptors for longer duration of activity. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2015, 172, 3522–3536.

- Mortensen, M.; Kristiansen, U.; Ebert, B.; Frølund, B.; Krogsgaard-Larsen, P.; Smart, T.G. Activation of single heteromeric GABAA receptor ion channels by full and partial agonists. J. Physiol. 2004, 557, 389–413.

- Zhu, S.; Noviello, C.M.; Teng, J.; Walsh, R.M., Jr.; Kim, J.J.; Hibbs, R.E. Structure of a human synaptic GABAA receptor. Nature 2018, 559, 67–72.

- Phulera, S.; Zhu, H.; Yu, J.; Claxton, D.P.; Yoder, N.; Yoshioka, C.; Gouaux, E. Cryo-EM structure of the benzodiazepine-sensitive α1β1γ2S tri-heteromeric GABAA receptor in complex with GABA. eLife 2018, 7, 39383.

- Laverty, D.; Desai, R.; Uchański, T.; Masiulis, S.; Stec, W.J.; Malinauskas, T.; Zivanov, J.; Pardon, E.; Steyaert, J.; Miller, K.W.; et al. Cryo-EM structure of the human α1β3γ2 GABAA receptor in a lipid bilayer. Nature 2019, 565, 516–520.

- Masiulis, S.; Desai, R.; Uchański, T.; Martin, I.S.; Laverty, D.; Karia, D.; Malinauskas, T.; Zivanov, J.; Pardon, E.; Kotecha, A.; et al. GABAA receptor signalling mechanisms revealed by structural pharmacology. Nature 2019, 565, 454–459.

- Kim, J.J.; Gharpure, A.; Teng, J.; Zhuang, Y.; Howard, R.J.; Zhu, S.; Noviello, C.M.; Walsh, R.M., Jr.; Lindahl, E.; Hibbs, R.E. Shared structural mechanisms of general anaesthetics and benzodiazepines. Nature 2020, 585, 303–308.

- Sente, A.; Desai, R.; Naydenova, K.; Malinauskas, T.; Jounaidi, Y.; Miehling, J.; Zhou, X.; Masiulis, S.; Hardwick, S.W.; Chirgadze, D.Y.; et al. Differential assembly diversifies GABAA receptor structures and signalling. Nature 2022, 604, 190–194.

- Zhu, S.; Sridhar, A.; Teng, J.; Howard, R.J.; Lindahl, E.; Hibbs, R.E. Structural and dynamic mechanisms of GABAA receptor modulators with opposing activities. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4582.

- Nemecz, Á.; Prevost, M.S.; Menny, A.; Corringer, P.-J. Emerging Molecular Mechanisms of Signal Transduction in Pentameric Ligand-Gated Ion Channels. Neuron 2016, 90, 452–470.

- Kim, J.J.; Hibbs, R.E. Direct Structural Insights into GABAA Receptor Pharmacology. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2021, 46, 502–517.

- Pflanz, N.C.; Daszkowski, A.W.; Cornelison, G.L.; Trudell, J.R.; Mihic, S.J. An intersubunit electrostatic interaction in the GABAA receptor facilitates its responses to benzodiazepines. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 8264–8274.

- Venkatachalan, S.P.; Czajkowski, C. Structural Link between γ-Aminobutyric Acid Type A (GABAA) Receptor Agonist Binding Site and Inner β-Sheet Governs Channel Activation and Allosteric Drug Modulation. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 6714–6724.

- Terejko, K.; Michałowski, M.A.; Dominik, A.; Andrzejczak, A.; Mozrzymas, J.W. Interaction between GABAA receptor α1 and β2 subunits at the N-terminal peripheral regions is crucial for receptor binding and gating. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2020, 183, 114338.

- Baur, R.; Sigel, E. Benzodiazepines Affect Channel Opening of GABAA Receptors Induced by Either Agonist Binding Site. Mol. Pharmacol. 2005, 67, 1005–1008.

- Goldschen-Ohm, M.P.; Wagner, D.A.; Petrou, S.; Jones, M.V. An Epilepsy-Related Region in the GABAA Receptor Mediates Long-Distance Effects on GABA and Benzodiazepine Binding Sites. Mol. Pharmacol. 2009, 77, 35–45.

- Yu, J.; Zhu, H.; Lape, R.; Greiner, T.; Du, J.; Lü, W.; Sivilotti, L.; Gouaux, E. Mechanism of gating and partial agonist action in the glycine receptor. Cell 2021, 184, 957–968.e21.

- Hibbs, R.E.; Sulzenbacher, G.; Shi, J.; Talley, T.; Conrod, S.; Kem, W.R.; Taylor, P.; Marchot, P.; Bourne, Y. Structural determinants for interaction of partial agonists with acetylcholine binding protein and neuronal α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. EMBO J. 2009, 28, 3040–3051.

More

Information

Subjects:

Biochemistry & Molecular Biology

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

738

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

15 Dec 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No