You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Melinda Ildiko Mitranovici | -- | 1448 | 2022-12-13 17:24:34 | | | |

| 2 | Peter Tang | Meta information modification | 1448 | 2022-12-14 07:19:18 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Mitranovici, M.; Chiorean, D.M.; Mureșan, M.C.; Buicu, C.; Moraru, R.; Moraru, L.; Cotoi, T.C.; Cotoi, O.S.; Toru, H.S.; Apostol, A.; et al. Diagnosis and Management of Dysgerminomas. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/38710 (accessed on 21 December 2025).

Mitranovici M, Chiorean DM, Mureșan MC, Buicu C, Moraru R, Moraru L, et al. Diagnosis and Management of Dysgerminomas. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/38710. Accessed December 21, 2025.

Mitranovici, Melinda-Ildiko, Diana Maria Chiorean, Maria Cezara Mureșan, Corneliu-Florin Buicu, Raluca Moraru, Liviu Moraru, Titiana Cornelia Cotoi, Ovidiu Simion Cotoi, Havva Serap Toru, Adrian Apostol, et al. "Diagnosis and Management of Dysgerminomas" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/38710 (accessed December 21, 2025).

Mitranovici, M., Chiorean, D.M., Mureșan, M.C., Buicu, C., Moraru, R., Moraru, L., Cotoi, T.C., Cotoi, O.S., Toru, H.S., Apostol, A., Turdean, S.G., Mărginean, C., Petre, I., Oală, I.E., Simon-Szabo, Z., Ivan, V., & Pușcașiu, L. (2022, December 13). Diagnosis and Management of Dysgerminomas. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/38710

Mitranovici, Melinda-Ildiko, et al. "Diagnosis and Management of Dysgerminomas." Encyclopedia. Web. 13 December, 2022.

Copy Citation

Dysgerminoma represents a rare malignant tumor composed of germ cells, originally from the embryonic gonads. Dysgerminoma occurs at a fertile age. The preferred treatment is the surgical removal of the tumor succeeded by the preservation of fertility.

dysgerminoma

OMGCTs

platinum-based therapy

1. Introduction

Dysgerminoma is a malignant tumor composed of germ cells histogenetically derived from the embryonic gonads, known as the equivalent of testicular seminoma, according to the World Health Organization (WHO) [1][2]. The most common type of nondysgerminomatous tumors are immature teratomas, endodermal sinus tumors (yolk sac), embryonal carcinomas, polyembryomas, choriocarcinomas and mixed germ cell tumors [2]. Tumors with primitive gonadal cells are histologically characterized by their development from primitive germ cells, which does not have a specific pattern of differentiation [3].

It is a rare tumor, most often originating from a dysgenetic gonad, with the presence of a Y chromosome. Among gonadoblastomas, dysgerminoma is the most common [4], first described by Scully et al. as a rare tumor with unknown prevalence [5]. It can be frequently associated with hermaphroditism, being first described by Swyer et al. in 1955 in a hermaphrodite with a 46XY karyotype and a female phenotype [6]. It occurs more frequently in adolescence/young adulthood [1][2], representing 1–2% of all ovarian neoplasia [2][7]. The etiopathogenic mechanism is not yet completely known [3]. It is one of the malignant germ cell tumors (OMGCT), which are heterogeneous tumors derived from the primitive germ cells of the embryonic gonads, and is rare, representing 2.6% of malignant ovarian tumors [8]. Dysgerminoma is the most frequent [8]. Regarding its incidence and epidemiology, there is no precise data due to the rare condition of the disease [9]. It is discovered more frequently in stage I, according to FIGO (International Federation of Obstetrics and Gynecology) staging, in a proportion of 75% [2][7]. These tumors are usually unilateral, but can also develop bilaterally, usually not accompanied by ascites [7].

Dysgerminoma occurs at fertile age, and we can find it in association with 2.8-11/100,000 of pregnant women [10][11][12]. In the literature, there are case reports presented with misdiagnosed dysgerminomas and confused with fibromas, including by ultrasound and MRI examinations. It is usually discovered during the caesarean section performed due to a dysfunctional labor caused by this previa tumor [13]. The follow-up also includes a PET (positron emission tomography) scan [10][13]. A multidisciplinary team formed by a gynecologic oncologist, a pediatric oncologist and a pediatric surgeon, under the guidance of the Malignant Germ Cell International Consortium (MaGIC) and founded in 2009, studies this type of tumor while important organizations such as the European Society of Gynecology Oncology (ESGO) and European Society for Pediatric Oncology (SIOPE) define the standards for diagnostic, treatment and follow-up [9].

The favorite treatment is the surgical removal of the tumor and the preservation of fertility [2][7][10][13][14], but, in the case of hermaphroditism, mixed germ cells tumor can develop, which leads to a more aggressive evolution, with a risk of malignancy in the bilateral of the gonads, which is why removal of both ovotestis is required [15]. Recurrence reaches 20% in 2 years, after being successfully treated by adjuvant methods, chemotherapy with platinum-based therapy with good efficiency and tolerability and, rarely, radiotherapy [7].

2. Diagnosis

Symptoms of this disease are pelvic pain, tumoral mass with abdominal distention, amenorrhea, sometimes bleeding and compression of the neighboring organs, but it can also be asymptomatic [2][7][9][13]. However, the main symptom is represented by pelvic and abdominal pain, which can be acute, in the case of rupture, torsion or hemorrhage [7][11][16][17][18][19]. Family history is usually insignificant for this pathology [20]; moreover, the family history of cancer inversely correlates with the development of germ cell tumors [9]. Personal history is irrelevant as well [20]. The clinical diagnosis, along with the described symptoms, would be the general appearance of hermaphroditism in some specific cases and sexual ambiguity [21], palpable abdominal mass tumor, abdominal distension [6][9][11] or tumors in the inguinal region [21].

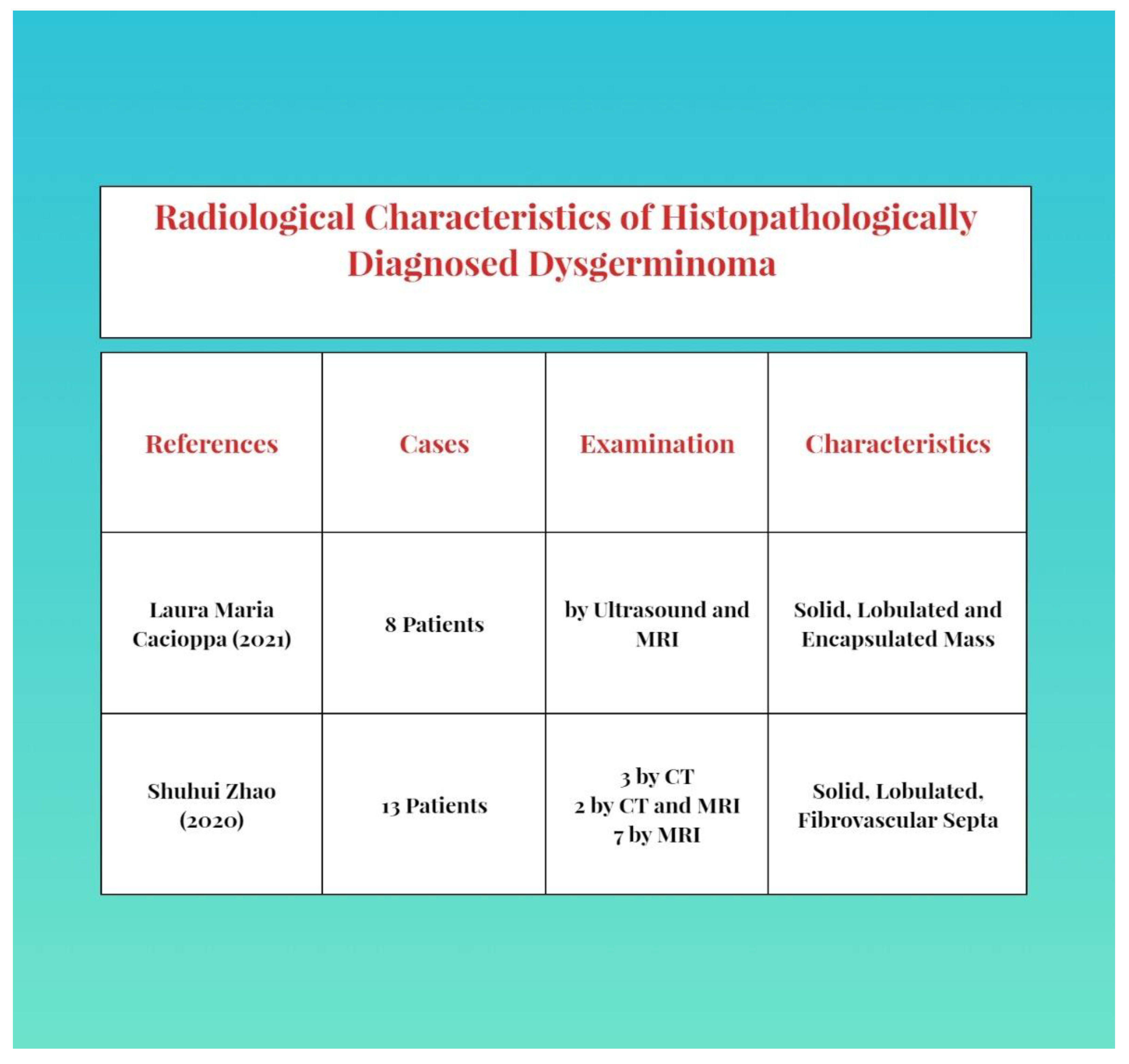

As imaging, abdominal and more frequently transvaginal ultrasounds and the associated Doppler velocimetry can be used [2][9]. The characteristics are a solid, multilobulated, heterogeneous tumor mass, separated from the uterus, with fibrous septa and an irregular appearance. Anechoic areas of necrosis or intratumoral hemorrhage can be found. During a Doppler examination, a low resistance flow can be found [2][3]. A similar aspect can be found in an MRI [8][9][18][22]. A CT scan is used less often, as an ultrasound and MRI are more specific for diagnosis [23]. The description of the aspects and common features of examination are presented as follows in Figure 1.

For detection of metastases and pleurisy, a chest X-ray would be useful [9]. Follow-up includes a PET scan (positron emission tomography) [9][10][13].

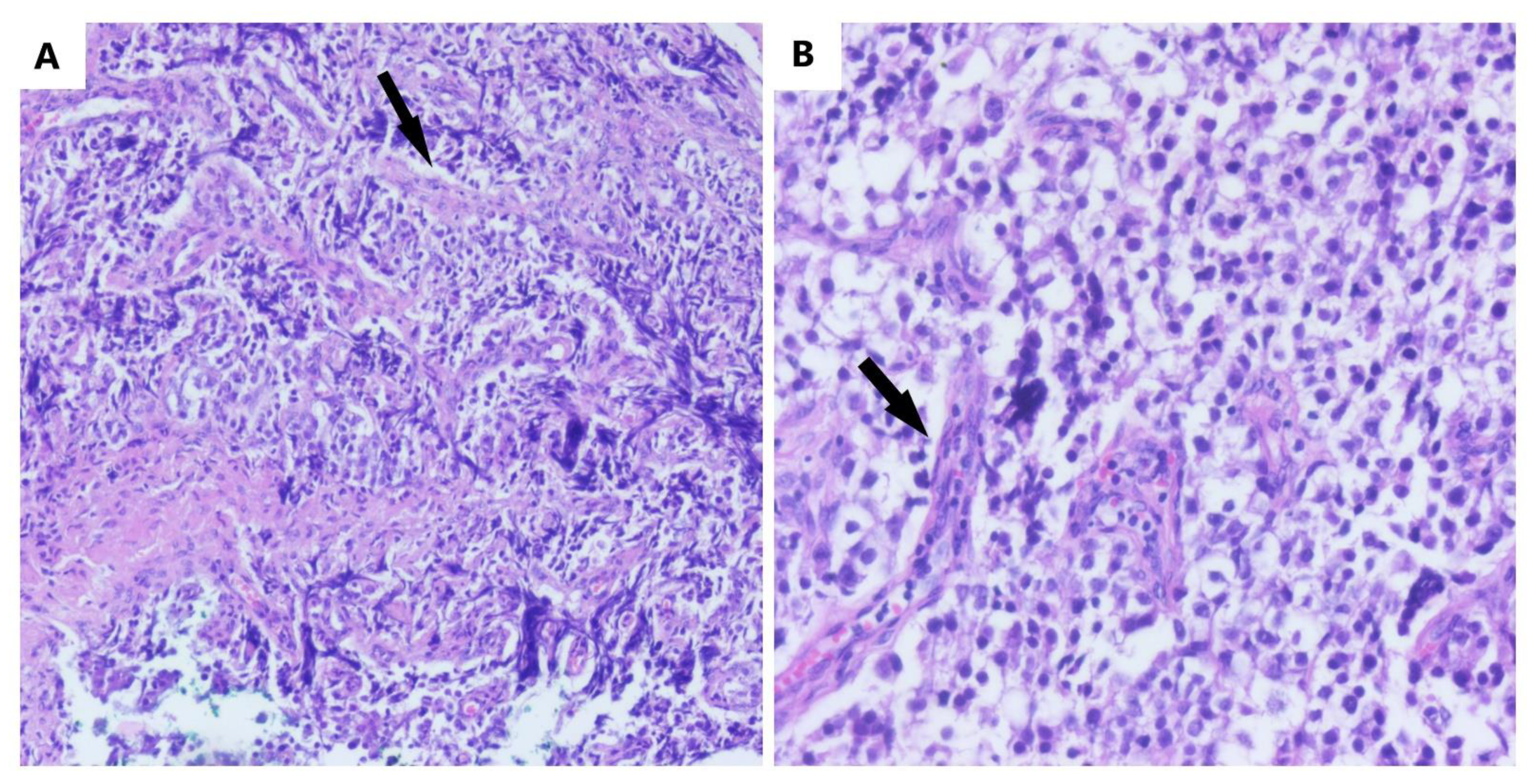

A histopathological examination establishes the final diagnosis. The macroscopy reveals gray-whitish tumors, which are encapsulated and rarely bilateral and sometimes have areas of necrosis and hemorrhage [21]. The microscopic aspect is characterized by the nests and nodules of uniform tumor cells, which are separated by fine connective tissue, containing inflammatory cells. The tumor cells are polygonal in shape, with clearly visible cell borders, with an eosinophilic to clear cytoplasm that is centrally located, with a round nucleus and prominent nucleoli (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The microscopic aspect of dysgerminoma: (A) nests and nodules of uniform tumor cells, which are polygonal in shape, with clear-visible cell borders, an eosinophilic-to-clear cytoplasm and centrally located nucleus, separated by fine connective tissue containing inflammatory cells (black arrows) (HE, ob. 10×); (B) details of the described area (HE, ob. 20×).

It can be admixed with cord derivatives, such as Sertoli or granulosa cells. Calcifications can also be present. Ovarian stromal cells only appear focally. It can be mapped to the Y chromosome, which could be detected, and to the 12 chromosome’s p arm [24][25]. In addition, for a complete and correct diagnosis, especially in the case of hermaphroditism, the determination of the karyotype is requested, possibly with a buccal swab for the SRY gene mutation as well [5][6][20][26]. In addition, in gonadoblastomas, it would be useful to search for DNA sequencing and for the status of the 12 chromosome’s p arm from the tumor cells, by cytophotometry and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), especially since this is associated with reserved prognosis and additional therapy [24]. Valuable biomarkers for the diagnosis, differential diagnosis and follow-up of post-therapeutic evolution are BHCG (beta-human chorionic gonadotropin) [2][4][9], LDH (lactate dehydrogenase) [2][4][10][13] and AFP (alpha-fetoprotein) [13], which can be negative [3]. For a differential diagnosis with other ovarian tumors, cancer antigen 125 (CA-125) can be used [9]. The differential diagnosis is made with early or ectopic pregnancy, due to the presence of BHCG [4][27], uterine fibroids [10], other forms of acute abdomen [10], lymphoma or leukemia in case of atypical skin or breast metastases [28] and endometriosis [14].

Dysgerminomas can complicate by rupture, torsion, hemorrhage or incarceration [9][10][11]. Either they can give local metastases (neighboring tissue), via lymphatic, or distant hematogenous metastases in bones, lungs, the omentum, kidneys [3][8], the breast and skin (rarely but aggressively) [12][13] or the neck [14]. Confirmation diagnosis for germinoma metastasis is made by histopathological examination using immunohistochemistry [14][28].

3. Management

Management in the case of this diagnosis would be primarily surgical. Minimally invasive interventions are preferred. Sometimes laparoscopy does not detect pathological lesions [27]; in this case, biopsies are performed. If there are changes suggestive of hermaphroditism, the researchers prefer the removal of the gonads in the first attempt or in two stages, due to the malignancy capacity of the ovotestis [3][6]. In these situations, most of the time, the gonads are found in the inguinal canal [6]. However, in the case of typical dysgerminoma, the researchers prefer a unilateral oophorectomy with the preservation of fertility [2][9][10][13][14]. Tumor cytoreduction is followed by the best survival [8][17]. Multiple peritoneal and epiploic biopsies are associated only if we find abnormalities [8], with peritoneal washings preferred [9]. In some complicated situations, a hysterectomy was also required [29], though only in an advanced stage (II or III), sometimes with a lymphadenectomy [8]. In some cases, these extensive interventions are even abandoned when fertility preservation is desired [8]. In some studies, lymphadenectomy and omentectomy are even recommended as the first intention [19], but this is not supported by the majority of studies [7][8][17]. The postoperative outcome is adequate. Postoperatively, adjuvant chemotherapy may or may not be required [7]. For example, platinum-based therapy [8] can improve the prognosis [6] with a survival of 100% in early-stage tumors and 75% in advanced-stage tumors [8]. After gonadal removal, a hormone replacement therapy would be necessary [6][29]. Second-look surgery seems to have not demonstrated its usefulness, if there is no tumor recurrence or metastases or the biomarkers have not increased [8].

If diagnosed during pregnancy, it would be most appropriate to remove it surgically in the second trimester of pregnancy, at 16–18 weeks, followed by adjuvant chemotherapy, either during pregnancy or after birth, depending on the intraoperative findings [10][11]. The survival rate is between 97–100%, with the preservation of fertility [2][10][11]. Even if diagnosed in advanced stages, the survival rate is over 80% [11]. The solution, in case of gonadal removal, is represented by the assisted human reproduction technique, egg donation and embryo transfer [29].

References

- Tsutsumi, M.; Miura, H.; Inagaki, H.; Shinkai, Y.; Kato, A.; Kato, T.; Hamada-Tsutsumi, S.; Tanaka, M.; Kudo, K.; Yoshikawa, T.; et al. An aggressive systemic mastocytosis preceded by ovarian dysgerminoma. BMC Cancer 2020, 20, 1162.

- Michael, K.K.; Wampler, K.; Underwood, J.; Hansen, C. Ovarian Dysgerminoma: A Case Study. J. Diagn. Med. Sonogr. 2015, 31, 327–330.

- Tîrnovanu, M.C.; Florea, I.D.; Tănase, A.; Toma, B.F.; Cojocaru, E.; Ungureanu, C.; Lozneanu, L. Uncommon Metastasis of Ovarian Dysgerminoma: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Medicina 2021, 57, 534.

- Esin, S.; Baser, E.; Kucukozkan, T.; Magden, H.A. Ovarian gonadoblastoma with dysgerminoma in a 15-year-old girl with 46, XX karyotype: Case report and review of the literature. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2012, 285, 447–451.

- Sato, Y.; Hayashi, T.; Yamamoto, H.; Niina, I.; Kuroki, N.; Iwamura, T.; Onishi, J. Late Recurrence in Ovarian Dysgerminoma Presenting as a Primary Retroperitoneal Tumor: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Case Rep. Pathol. 2020, 2020, 4737606.

- Chen, C.Q.; Liu, Z.; Lu, Y.S.; Pan, M.; Huang, H. True hermaphroditism with dysgerminoma: A case report. Medicine 2020, 99, e20472.

- Husaini, H.A.L.; Soudy, H.; Darwish, A.E.D.; Ahmed, M.; Eltigani, A.; Mubarak, M.A.L.; Abu Sabaa, A.; Edesa, W.; A L-Tweigeri, T.; Al-Badawi, I.A. Pure dysgerminoma of the ovary: A single institutional experience of 65 patients. Med. Oncol. 2012, 29, 2944–2948.

- Keskin, M.; Savaş-Erdeve, Ş.; Kurnaz, E.; Çetinkaya, S.; Karaman, A.; Apaydın, S.; Aycan, Z. Gonadoblastoma in a patient with 46, XY complete gonadal dysgenesis. Turk. J. Pediatr. 2016, 58, 538–540.

- Arndt, M.; Taube, T.; Deubzer, H.; Calaminus, K.; Sehouli, J.; Pietzner, K. Management of malignant dysgerminoma of the ovary. Eur. J. Gynaecol. Oncol. 2022, 43, 353–362.

- Gupta, M.; Jindal, R.; Saini, V. An Incidental Finding of Bilateral Dysgerminoma during Cesarean Section: Dilemmas in Management. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2016, 10, QD04–QD05.

- Ajao, M.; Vachon, T.; Snyder, P. Ovarian dysgerminoma: A case report and literature review. Mil. Med. 2013, 178, e954–e955.

- Chen, Y.; Luo, Y.; Han, C.; Tian, W.; Yang, W.; Wang, Y.; Xue, F. Ovarian dysgerminoma in pregnancy: A case report and literature review. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2018, 19, 649–658.

- Thannickal, A.; Maddy, B.; DeWitt, M.; Cliby, W.; Dow, M. Dysfunctional labor and hemoperitoneum secondary to an incidentally discovered dysgerminoma: A case report. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021, 21, 611.

- Seilanian Toosi, F.; Hasanzadeh, M.; Maftouh, M.; Tavassoli, A. Cutaneous Metastasis in a Previously Known Case of Ovarian Dysgerminoma: A Case Report. Int. J. Cancer Manag. 2021, 14, e104715.

- De Jesus Escano, M.R.; Mejia Sang, M.E.; Reyes-Mugica, M.; Colaco, M.; Fox, J. Ovotesticular Disorder of Sex Development: Approach and Management of an Index Case in the Dominican Republic. Cureus 2021, 13, e18512.

- Ali, N.H.; Radhakrishnan, A.P.; Saaya, M.I. An Unusual Case of Ovarian Dysgerminoma Associated with Secondary Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis (HLH). Open Access Library J. 2022, 9, 1–6.

- Bandala-Jacques, A.; Estrada-Rivera, F.; Cantu, D.; Prada, D.; Montalvo-Esquivel, G.; González-Enciso, A.; Barquet-Munoz, S.A. Role of optimal cytoreduction in patients with dysgerminoma. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2019, 29, 1405–1410.

- Zhao, S.; Sun, F.; Bao, L.; Chu, C.; Li, H.; Yin, Q.; Guan, W.; Wang, D. Pure dysgerminoma of the ovary: CT and MRI features with pathological correlation in 13 tumors. J. Ovarian Res. 2020, 13, 71.

- Kilic, C.; Cakir, C.; Yuksel, D.; Kilic, F.; Kayikcioglu, F.; Koc, S.; Korkmaz, V.; Kimyon Comert, G.; Turkmen, O.; Boran, N.; et al. Ovarian Dysgerminoma: A Tertiary Center Experience. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2021, 10, 303–308.

- Kota, S.K.; Gayatri, K.; Pani, J.P.; Kota, S.K.; Meher, L.K.; Modi, K.D. Dysgerminoma in a female with turner syndrome and Y chromosome material: A case-based review of literature. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 16, 436–440.

- Khare, M.; Gupta, M.K.; Airun, A.; Sharma, U.B.; Garg, K. A Case of True Hemaphroditism Presenting with Dysgerminoma. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2017, 11, ED07–ED09.

- Tsuboyama, T.; Hori, Y.; Hori, M.; Onishi, H.; Tatsumi, M.; Sakane, M.; Ota, T.; Tomiyama, N. Imaging findings of ovarian dysgerminoma with emphasis on multiplicity and vascular architecture: Pathogenic implications. Abdom. Radiol. 2018, 43, 1515–1523.

- Cacioppa, L.M.; Crusco, F.; Marchetti, F.; Duranti, M.; Renzulli, M.; Golfieri, R. Magnetic resonance imaging of pure ovarian dysgerminoma: A series of eight cases. Cancer Imaging 2021, 21, 58.

- Changchien, Y.C.; Haltrich, I.; Micsik, T.; Kiss, E.; Fónyad, L.; Papp, G.; Sápi, Z. Gonadoblastoma: Case report of two young patients with isochromosome 12p found in the dysgerminoma overgrowth component in one case. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2012, 208, 628–632.

- Batool, A.; Karimi, N.; Wu, X.N.; Chen, S.R.; Liu, Y.X. Testicular germ cell tumor: A comprehensive review. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2019, 76, 1713–1727.

- Govindaraj, S.K.; Muralidhar, L.; Venkatesh, S.; Saxena, R.K. Disorder of Sexual Development with Sex Chromosome Mosaicism 46 XY and 47 XXY. Int. J. Infertil. Fetal Med. 2013, 4, 34–37.

- Cormio, G.; Seckl, M.J.; Loizzi, V.; Resta, L.; Cicinelli, E. Increased human Chorionic Gonadotropin levels five years before diagnosis of an ovarian dysgerminoma. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2018, 220, 138–139.

- Adekunle, O.; Zayyan, M.; Kolawole, A.; Ahmed, S. Case report: A rare case of dysgerminoma presenting with skin and breast metastasis. Case Rep. Clin. Med. 2013, 2, 170–172.

- Milewicz, T.; Mrozińska, S.; Szczepański, W.; Białas, M.; Kiałka, M.; Doroszewska, K.; Kabzińska-Turek, M.; Wojtyś, A.; Ludwin, A.; Chmura, Ł. Dysgerminoma and gonadoblastoma in the course of Swyer syndrome. Pol. J. Pathol. 2016, 67, 411–414.

More

Information

Subjects:

Obstetrics & Gynaecology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.1K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

14 Dec 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No