Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Endre Sulyok | -- | 1734 | 2022-12-12 08:39:11 | | | |

| 2 | Camila Xu | -26 word(s) | 1708 | 2022-12-15 09:54:33 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Bodis, J.; Farkas, B.; Nagy, B.; Kovacs, K.; Sulyok, E. Clinical and Physiological Significance of L-Arginine Methabolism. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/38562 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Bodis J, Farkas B, Nagy B, Kovacs K, Sulyok E. Clinical and Physiological Significance of L-Arginine Methabolism. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/38562. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Bodis, Jozsef, Balint Farkas, Bernadett Nagy, Kalman Kovacs, Endre Sulyok. "Clinical and Physiological Significance of L-Arginine Methabolism" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/38562 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Bodis, J., Farkas, B., Nagy, B., Kovacs, K., & Sulyok, E. (2022, December 12). Clinical and Physiological Significance of L-Arginine Methabolism. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/38562

Bodis, Jozsef, et al. "Clinical and Physiological Significance of L-Arginine Methabolism." Encyclopedia. Web. 12 December, 2022.

Copy Citation

L-arginine is transported by members of the cationic amino acid transporter (CAT) family. This transport system is Na+-independent, pH-insensitive, and activated by hyper-polarization and substrate trans-stimulation.

l-arginine

methylarginines

nitric oxide

oxidative stress

1. Introduction

Since the discovery of the l-arginine-NO system, great progress has been made in our understanding of its physiological role and clinical implications [1]. Most studies have been published in the field of cardiology, nephrology, neurology, neuroendocrinology, immunology/inflammation, and fertility in an attempt to delineate NO involvement in complex, interacting biological processes. In addition to its major role in maintaining vascular homeostasis by controlling vascular tone, by inhibiting platelet and leukocyte /monocyte adhesion to the endothelium, as well as by inhibiting the growth and proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells, NO exerts cell/tissue-specific autocrine/paracrine function [2]. Moreover, NO/NOS proved to be a critical player in signal transduction and transcription factor regulation.

2. Clinical and Physiological Significance of L-Arginine Methabolism

2.1. L-Arginine Transport into the Cells

Amino acid uptake is an essential part of cellular metabolism and required for protein synthesis and numerous enzymatic reactions. Associations have been proven between the turnover rate of amino acids and the developmental potential of oocytes and early embryos. Cellular uptake of individual amino acids or a certain group of amino acids is achieved by separate, well-defined transporters that are encoded by different genes. L-arginine is transported by members of the cationic amino acid transporter (CAT) family. This transport system is Na+-independent, pH-insensitive, and activated by hyper-polarization and substrate trans-stimulation. CAT-1, CAT-2B, and CAT-3 isoforms are involved in arginine transport that are encoded by the respective genes of the solute carrier (SLC) gene families. CAT-2A is a split variant without transport activity. Isoform 1 has been identified as a low-affinity, high-capacity transporter that enhances the cellular uptake of cationic arginine, lysine, and ornithine, while isoform 2B mediates the transport of these same amino acids but with much higher affinity for arginine than isoform 1 [3].

The major characteristics of amino acid transport systems in early mouse embryo development have been explored by Van Winkle et al. It has been demonstrated that these systems are developmentally regulated to meet the requirements of rapid growth and differentiation. Accordingly, the most highly expressed transport proteins for arginine have been identified in oocytes (CAT-2, CAT-1), in two-or-eight-cell embryo and blastocyste (CAT-1/CAT-2). It was supposed that the co-expression of CAT-1 and CAT-2 might be accounted for by at least two distinct transport activities of the superfamily they belong to. The abundance of corresponding mRNAs expression has also been demonstrated in mouse embryos at different stages of preimplantation development. As the same amino acid transport systems are operating in humans, it is reasonable to assume that the developmental pattern seen in mouse embryos may apply for human preimplantation embryos [4]. In support of this notion, microarray studies of human oocytes revealed the presence of genes encoding members of the transport systems mediating the cellular uptake of l-arginine [5]. Furthermore, mRNAs for cationic amino acid transporters (SLC7A1, SLC7A2, and SLC7A3) have been detected in ovine uterus epithelia and in the trophectoderm and endoderm of peri-implantation conceptus. The abundance of SLC7A1 and SLC7A2 has been enhanced by the estrous cycle and pregnancy and progesterone treatment, whereas that of SLC7A3 proved to be unaffected by either of these conditions [6].

Importantly, arginine transport is also accomplished via the B+o transport systems that mediate cellular accumulation of leucine, tryptophan, and arginine, with particular preference to arginine. These systems are operating already in the early embryonic development, therefore, they have been claimed to deplete amino acids from uterine secretions, to suppress T cell proliferation, and to protect implanted embryos from rejection [4].

With respect to tryptophan uptake by B+ transport system, it is to be stressed that this essential amino acid is the substrate of two competing metabolic pathways: the tryptophan-kynurenine and the tryptophan-serotonin (5-HT) pathways [7]. Convincing evidence have been provided for the essential role of tryptophan catabolism to both 5-HT and kynurenine in oocyte maturation, fertilization, implantation, and early embryonic/fetal development. In fact, embryo viability has been shown to be enhanced through 5-HT signaling as the paracrine/autocrine function of the serotoninergic network is required in the earliest embryonic development [7][8][9][10]. On the other hand, activation of kynurenine pathways resulted in decreased number of CD45-positive leukocytes and provided a possible immunological mechanism to establish embryo tolerance in early pregnancy [11].

The immune protection of embryo by kynurenines is further supported by the observations that with progressing pregnancy, IDO (indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase, the enzyme initiating tryptophan catabolism) expression is up-regulated by inflammatory cytokines including its most potent stimulant, interferon gamma, and immunosuppressive kynurenines are generated [12]. Conversely, IDO inhibition with methyl-tryptophan, or deletion of IDO gene caused pregnancy complications and fetal compromise [13][14]. It can be concluded, therefore, that adequate tryptophan supply for the generation of 5-HT and kynurenines is critical for the success of reproduction, and the two metabolic pathways should be kept in balance, although in IVF patients the tryptophan-5-HT pathways prevailed over tryptophan-kynurenine pathway when chemical/clinical pregnancy could be achieved [7].

2.2. The Process of Arginine Methylation

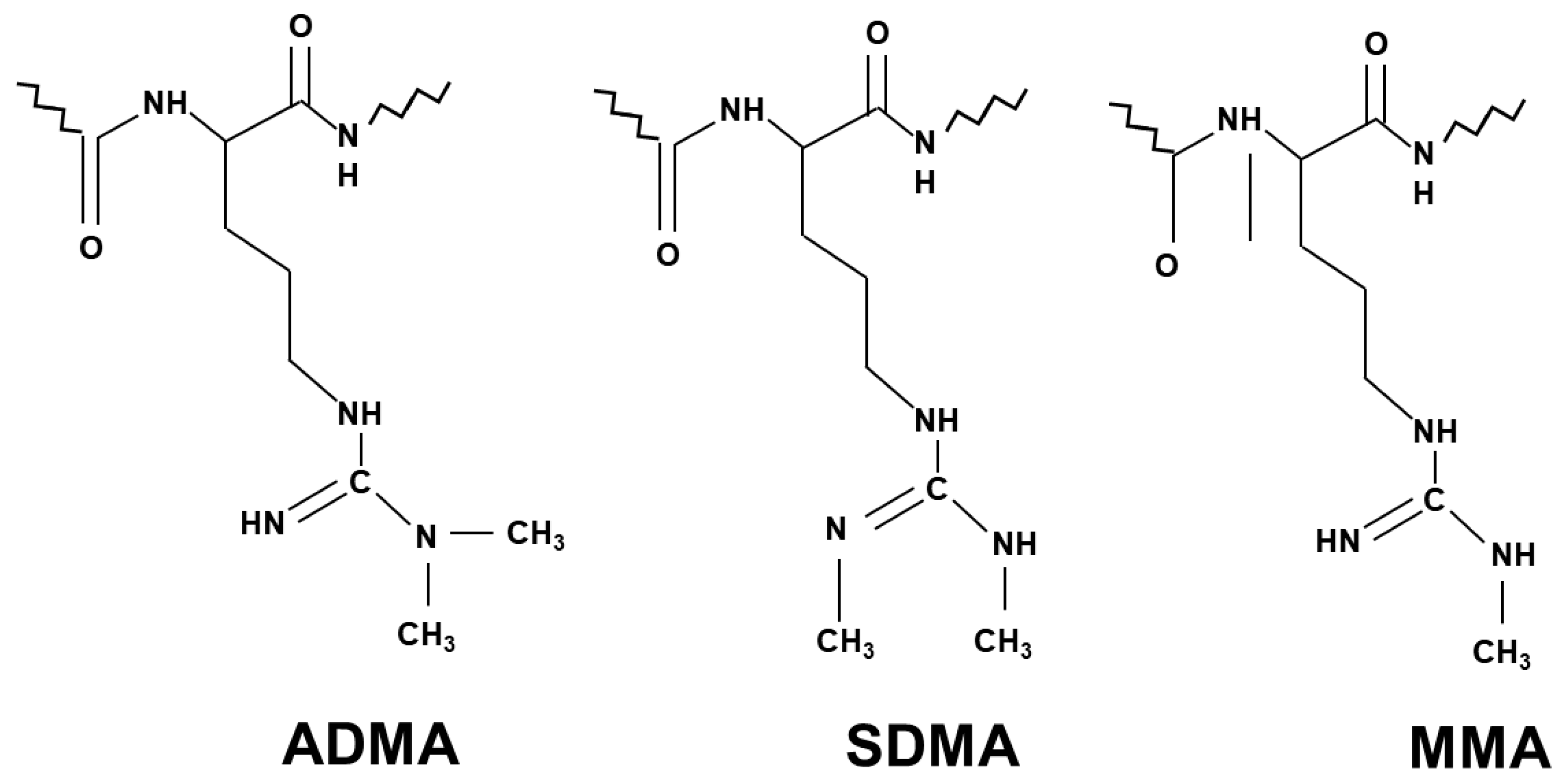

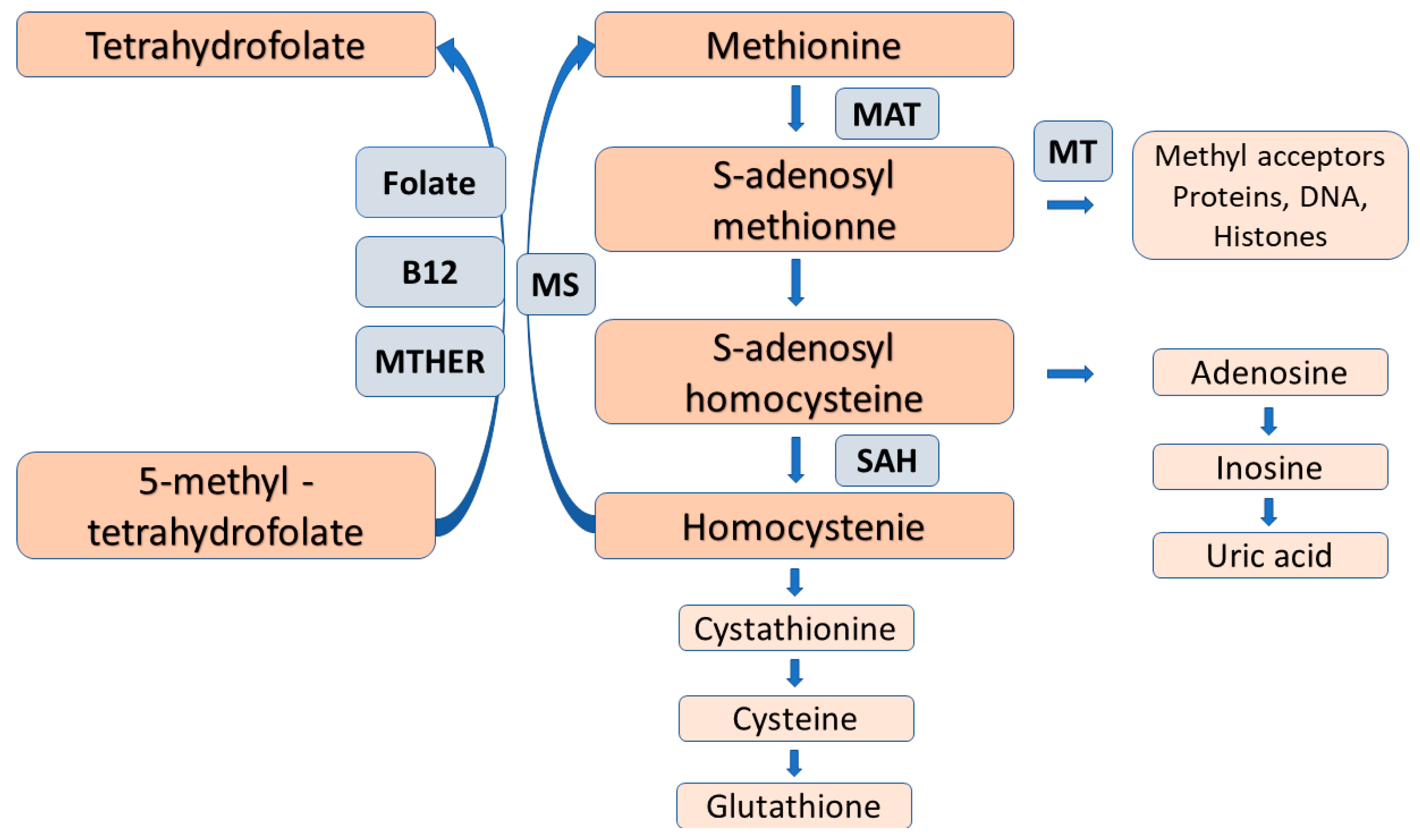

NO generation is mainly controlled by methylarginines. Asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) and monomethylarginine (MMA) competitively inhibit NOS isoforms, while MMA and symmetric dimethylarginine (SDMA) inhibit cellular uptake of l-arginine by cationic amino acid transporters [15] (Figure 1). Methyl groups for the methylation of arginine residues of proteins are provided by the folate-dependent homocysteine/methionine cycle. In this metabolic pathway, methionine is initially activated by ATP to S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) that serves as methyl donor for methyltransferases to add methyl groups to substrates including proteins, histones, DNAs and RNAs [16].

Figure 1. Chemical structure of the three different methylarginines.

After methyl transfer, SAM is converted to S-adenosylhomocysteine (SAH) that may undergo hydrolysis to homocysteine and adenosine. To prevent homocysteine accumulation, it is remethylated to methionine by the vitamin B12- and folate-dependent enzymes; methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase and methionine synthase (Figure 1). Inadequate dietary folate supply and/or gene polymorphisms of the remethylation enzymes may compromise the function of methionine/homocysteine circle with subsequent elevation of plasma homocysteine levels, and reduced methyl group generation for transmethylation reaction that may be associated with adverse clinical consequences [17][18][19].

With respect to female reproduction, folate insufficiency and homocysteine excess were found to result in multiple developmental abnormalities, recurrent early miscarriage, pre-eclampsia, and low birth weight. Folate/vitamin B12 supplement proved to reduce these complications by overcoming methionine trap and by re-establishing the functional integrity of the methionine /homocysteine circle [16][17][18][19][20].

Concerning NO production, inhibitory methylarginines are formed by protein arginine methyltransferases (type I PRMT and type II PRMT) via immediate precursor protein MMA, then it is catabolized to ADMA (type I PRMT) and SDMA (type II PRMT). After proteolysis, these methylarginines are released, and in their free form they exert their biological action. Accelerated proteolysis of proteins with methylated arginine residues and/or their reduced elimination may result in the accumulation of methylarginines. ADMA and MMA are mainly metabolized by dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolases (DDAHs) to dimethylamine and citrulline, while SDMA is removed by urinary excretion [15].

A great body of evidence indicates that methylarginines, especially ADMA and the integrated index of arginine methylation (arg-MI), is a well-established marker and mediator of the progression of cardiovascular and renal diseases [21]. With these observations in line, researchers' group reported significant inverse relationships of the number of oocytes retrieved and that of the embryos conceived to follicular fluid l-arginine, ADMA, SDMA, and MMA levels, respectively, in women undergoing IVF. Furthermore, higher FF methylarginine levels had negative impact on IVF outcome in terms of pregnancy rate. Importantly, no differences were noted in the l-arginine/ADMA ratio, an estimate of NO bioavailability, between groups of different IVF outcome [22].

These seemingly conflicting findings can be reconciled by assuming that to a certain extent, methylated arginines may influence the reproductive performance independent of NOS inhibition and NO generation. Consistent with this notion, methylarginines have also been shown to act beyond direct NOS inhibition in patients undergoing cardiac evaluation [21]. The concern about the high rate of methylation is further emphasized by the observations that members of PRMT family mediate the methylation of arginine residues in several nuclear and cytoplasmic protein substrates. Therefore, it may interfere with multiple cellular functions including signal transduction, transcription factor activation, RNA splicing, chromatin remodeling, DNA damage repairs, and protein-protein interaction [23][24].

The involvement of PRMTs in oocyte maturation and early embryo development has been well-documented. Altered patterns of their ovarian gene expression and dysregulation of PRMTs mediating post-translational modifications of histone protein and DNA may be associated with poor quality oocytes and compromised developmental potential. In support of this notion, the essential role of PRMTs in genome maintenance, cell proliferation, folliculogenesis, and post-implantation development has been demonstrated [25][26][27][28][29].

A recent mRNA-seq and genome-wide DNA methylation study of human ovarian granulosa cells demonstrated significant non-random changes in transcriptome and DNA methylome features as women age and their ovarian functions deteriorate. Increased methylation in highly methylated regions and decreased methylation in poorly methylated regions were equally associated with age-related decline in ovarian function [30]. Methylation of arginine residues of histone and non-histone proteins are also thought to be an important regulator of cellular functions, in particular, the structure and function of DNA, so it may also contribute to epigenetic modifications [30] (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The folate-dependent methionine-homocysteine cycle. Trans-sulfuration of homocysteine for cysteine and glutathione, as well as folate deficiency reduce the reaction by methionine synthase and causes homocysteine accumulation with the subsequent inhibition of the conversion of 5-methyl-tetrahydroforate to the metabolically active folate, tetrahydrofolate. Abbreviations: MAT = methionine adenosyltransferase, MT = methyltransferase, SAAH = S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase, MS = methionine synthase, MTAFR = methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase.

Taken together, methyl groups are generated as a normal product of cellular metabolism and have a regulatory role in several cellular processes. However, both a low rate and the excessively high rate of methylation have the potential to cause cellular dysfunction, to interfere with the finely tuned, complex interactions of metabolic pathways related to or independent of NO production. As a result, it may compromise healthy development of oocytes and embryos with subsequent pregnancy failure/complications. Unfortunately, the narrow range of methylation optimum has not been defined, therefore, efforts should be made to determine the upper and lower limit of methylation normality outside of which higher risk of fertilization and pregnancy success can be anticipated.we

References

- Furchgott, R.F.; Zawadzki, J.V. The obligatory role of endothelial cells in the relaxation of arterial smooth muscle by acetylcholine. Nature 1980, 288, 373–376.

- Cziraki, A.; Lenkey, Z.; Sulyok, E.; Szokodi, I.; Koller, A. L-arginine-nitric oxide-asymmetric dimethylarginine pathway and the coronary circulation: Translation of basic science results to clinical practice. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11.

- Closs, E.I.; Boissel, A.; Habermeier, A.; Rotmann, A. Structure and function of cationic amino acid transporters (CATs). J. Membr. Biol. 2006, 213, 67–77.

- Van Winkle, L.J. Amino acid transport and metabolism regulate early embryo development: Species differences, clinical significance and evolutionary implications. Cells 2010, 10, 3154.

- Bermúdez, M.; Wellis, D.; Malter, H.; Munné, S.; Cohen, J.; Steuerwald, N.M. Expression profiles of individual human oocytes using microarray technology. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2004, 3, 325–337.

- Gao, H.; Wu, G.; Spencer, T.E.; Johnson, G.A.; Bazer, F.W. Select nutrients in the ovine uterine lumen. III. Cationic amino acid transporters in the ovine uterus and peri-implantation conceptuses. Biol. Reprod. 2009, 80, 602–609.

- Bódis, J.; Sulyok, E.; Koppán, M.; Várnagy, Á.; Prémusz, V.; Gödöny, K.; Rascher, W.; Rauh, M. Tryptophan catabolism to serotonin and kynurenine in women undergoing in-vitro fertilization. Psihol. Res. 2020, 69, 1113–1124.

- Vesela, J.; Rehak, P.; Mihalik, J.; Czikkova, S.; Pokorny, J. Expression of serotonin receptors in mouse oocytes and preimplantation embryos. Psyhol. Res. 2003, 52, 223–228.

- Il’ Kova, G.; Rehak, P.; Vesela, J.; Cikos, S.; Fabian, D.; Czikkova, S.; Koppel, J. Serotonin localization and its functional significance during mouse preimplantation embryo development. Zygote 2004, 12, 205–213.

- Amireault, P.; Dube, F. Intracellular cAMP and calcium signalling by serotonin in mouse cumulus-oocyte complexes. Mol. Pharmacol. 2005, 68, 1678–1687.

- Groebner, A.E.; Schulke, K.; Schefold, J.C.; Fusch, G.; Singowatz, F.; Reichenbach, H.D.; Wolf, E.; Meyer, H.H.; Ulbrich, S.E. Immunological mechanisms to establish embryo tolerance in early bovine pregnancy. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 2011, 23, 619–632.

- Schrocksnadel, H.; Baier-Bitterlich, G.; Dapunt, O.; Wachter, H.; Fuchs, D. Decreased plasma tryptophan in pregnancy. Obstet. Gynecol. 1996, 88, 47–50.

- Munn, D.H.; Shafizadeh, E.; Attwood, J.T.; Bondarev, I.; Passhine, A.; Mellor, A.L. Inhibition of T cell proliferation by macrophage tryptophan catabolism. Exp. Med. 1999, 189, 1363–1372.

- Santillan, M.K.; Pelham, C.J.; Ketsawatsomkron, P.; Santillan, D.A.; Davis, D.R.; Devor, E.J.; Gibson-Corley, K.N.; Scroggins, S.M.; Grobe, J.L.; Yang, B.; et al. Pregnant mice lacking indoleamine 2,3-digoxygenase exhibit preeclampsia phenotypes. Physiol. Rep. 2015, 3, 1–9.

- Vallance, P.; Leone, A.; Calvcer, A.; Collier, J.; Moncada, S. Accumulation of an endogenous inhibitor of NO synthesis in chronic renal failure. Lancet 1992, 339, 572–575.

- Lucock, M. Follic acid: Nutritional biochemistry, molecular biology, and role in disease processes. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2000, 71, 121–138.

- Pogribna, M.; Melnyk, S.; Pogribny, I.; Chango, A.; Yi, P.; James, S.J. Homocystine metabolism in children with Down syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2001, 69, 88–95.

- Hobbes, C.A.; Cleves, M.A.; Melnyk, S.; Zhao, W.; James, S.J. Congenital heart defects and abnormal maternal biomarkers of methionine and homocysteine metabolism. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 81, 147–153.

- Shea, T.B.; Rogeres, E. Lifetime requirement of the methionine cycle for neuronal development and maintenance. Cuur. Opin. Psychiatry 2014, 27, 138–142. Available online: www.co-psychiatry.com (accessed on 1 January 2021).

- Baumann, C.B.; Olson, M.; Wang, K.; Fazleabas, A.; De La Funte, R. Arginine methyltransferases mediate an epigenetic ovarian response to endometriosis. Reproduction 2015, 150, 297–331.

- Wang, Z.; Tang, W.W.H.; Cho, L.; Brennan, D.M.; Haten, S.L. Targeted metabolomics evaluation of arginine methylation and cardiovascular risk. Potential Mechanisms beyond nitric oxide synthase inhibition. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2009, 29, 1383–1391.

- Bódis, J.; Várnagy, Á.; Sulyok, E.; Kovács, G.L.; Martens-Lobenhoffer, J.; Bode-Böger, S.M. Negative association of l-arginine methylation products with oocyte numbers. Hum. Reprod. Adv. Acc. 2010, 25, 3095–3100.

- Pahlich, S.; Zakaryan, R.P.; Gehring, H. Protein arginine methylation: Cellular functions and methods of analysis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2006, 1764, 1890–1903.

- Wolf, S.S. The protein aarginine methyltransferase family: An update about function, new perspectives and physiological role in humans. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2009, 66, 2109–2121.

- Pawlak, M.R.; Scherer, C.A.; Chen, J.I.N.; Roshon, M.J.; Ruley, H.E. Arginine N-methyltransferase 1 is required for early postimplantation mouse development, but cells deficient in the enzyme are viable. Mol. Cell Biol. 2000, 20, 4859–4869.

- Kim, S.; Günesdogan, U.; Zylicz, J.; Hackett, J.A.; Cougot, D.; Bao, S.; Lee, C.; Dietmann, S.; Allen, G.E.; Sengupta, R.; et al. PRMT5 Protects genomic integrity during global DNA demethylation in primordial germ cells and preimplantation embryos. Mol. Cell 2014, 56, 564–579.

- Zhu, J.; Zhang, D.; Liu, X.; Yu, G.; Cai, X.; Xu, C.; Rong, F. Zebrafish prmt5 arginine methyltransferase is essential for germ cell development. Development 2019, 146, 179572.

- Yadav, N.; Lee, J.; Kim, J.; Shen, J.; Hu, M.C.T.; Aldaz, C.M.; Mark, T.; Betford, T. Specific protein methylation defects and gene expression perturbations in coactivator-associated arginine methyltransferase 1-deficient mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 6464–6468.

- Chamani, I.J.; Keele, D. Epigenetics and female reproductive aging. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 473.

- Yu, B.; Russanova, V.R.; Gravina, S.; Hartley, S.; Mullikin, J.C.; Ignezweski, A.; Graham, J.; Segars, J.H.; De Cherney, A.H.; Howard, B.H. DNA methyloma and transcriptome sequencing in human ovarian granulosa cells links age-related changes in gene expression to gene body methylation and 3’-end CG density. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 3627–3643.

More

Information

Subjects:

Obstetrics & Gynaecology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

787

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

15 Dec 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No