Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Siti Baidurah | -- | 3097 | 2022-12-12 01:43:03 | | | |

| 2 | Rita Xu | Meta information modification | 3097 | 2022-12-14 08:49:54 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Baidurah, S. Physical Methods for Biodegradable Polymers. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/38509 (accessed on 08 February 2026).

Baidurah S. Physical Methods for Biodegradable Polymers. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/38509. Accessed February 08, 2026.

Baidurah, Siti. "Physical Methods for Biodegradable Polymers" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/38509 (accessed February 08, 2026).

Baidurah, S. (2022, December 12). Physical Methods for Biodegradable Polymers. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/38509

Baidurah, Siti. "Physical Methods for Biodegradable Polymers." Encyclopedia. Web. 12 December, 2022.

Copy Citation

Biodegradable polymers are materials that can decompose through the action of various environmental microorganisms, such as bacteria and fungi, to form water and carbon dioxide. The biodegradability characteristics have led to a growing demand for the accurate and precise determination of the degraded polymer composition. With the advancements in analytical product development, various analytical methods are available and touted as practical and preferable methods of bioanalytical techniques, which enable the understanding of the complex composition of biopolymers such as polyhydroxyalkanoates and poly(lactic acid).

biodegradation

biodegradable polymers

polyhydroxyalkanoates

1. Introduction

The plethora of current knowledge of biodegradable polymers has been supported by the selection of various analytical methods used by researchers. Since polymer degradation is an intricate process impacted by various parameters, it is improbable that any one selected method could provide a comprehensive picture of the changes in polymer degrading properties at both the macroscopic and chemical structure levels. Cross-comparisons of two or more independent methodologies can provide deeper knowledge of the degradation characteristics. The preferred approach for quantitatively measuring biodegradation rates should be simple, precise, quick, and economical. Comparisons of information collected using several analytical techniques should be conducted with caution, taking into account many parameters (the number of samples required, degree of sensitivity, etc.) that may contribute to inappropriate comparisons and inaccurate judgments. This research discusses the broad concepts, benefits, and drawbacks of the many methodologies available for studying biodegradable polymers, such as physical observation, chromatographic, spectroscopic, and respirometric methods, and meta-analysis, as delineated in Figure 1. In addition, the gaps in, and development of, the analytical methods are also highlighted.

Figure 1. Analytical methods of biodegradable polymers.

Biodegradable polymers are materials that can be decomposed through the action of various environmental microorganisms, such as bacteria and fungi, to form water and carbon dioxide [1]. The biodegradation mechanisms or decomposition begins on the polymer surface due to the action of the extracellular enzymes of microorganisms, generating oligomers. These corresponding oligomers then enter the microorganism cell, in which they act as carbon sources and are metabolized into carbon dioxide and water [1]. Biopolymers have garnered a great deal of interest as “green” or “environmentally friendly” polymetric materials owing to their degradability properties and low environmental load upon disposal [2][3][4][5][6][7]. To enhance their physical and thermo-chemical properties, biopolymers are often enhanced to improve their suitability for their final product applications. The enhancement is achieved by the incorporation of fillers, binders, or copolymers. These modified biopolymers are applied and produced widely on the industrial scale [8].

1.1. Examples of Biopolymers

Table 1 summarizes the classification of the current commercially available biodegradable polymers based on their origins, together with the trade names and manufacturers [9][10]. These polymers generally consist of polyesters and polysaccharides bearing hydrolysable ester or ether bonds in their backbones, respectively. They can be categorized according to their origins of production, namely bacteria, natural products, and chemical synthesis.

Table 1. Classification of typical commercially available biodegradable polymers based on their origins, together with the trade names and manufacturers [9][10].

| Origin | Polymer Name | Trade Name | Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Produced by bacteria | Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs), Polyhydroxy butyrate (PHB)  |

BiopolTM | Monsanto Company (St. Louis, MO, USA) |

Polyhydroxybutyrate-co-hydroxyvalerate [P(HB-co-HV)] |

Imperial Chemical Industries (London, UK) | ||

| Gellan gum | KelcogelR | Kelco Biopolymers (Atlanta, GA, USA) | |

| Curdlan | PureglucanR | Takeda Chemical Industries (Osaka, Japan) Nuture, Inc. (New York, NY, USA) |

|

| Produced from natural products and their derivatives | Amylose Amylopectine Starch |

Mater-BiR, VegematR |

Novamont (Novara, Italy) Vivadur (Bazet, French) |

| Chitin | - | Eastman Chemical Company (Kingsport, TN, USA) Primester (Kingsport, TN, USA) Celanese Ltd. (Irving, TX, USA) |

|

| Cellulose acetate (CA) | ChitoPureR | USA Biopolymer Engineering (Saint Paul, MN, USA) | |

| Produced via chemical synthesis | Polyglycolic acid (PGA) |

BiomaxR | Dupont (Wilmington, DE, USA) |

Polylactic acid (PLA) |

NatureWorksTM | Cargill Dow (Plymouth, MN, USA) Mitsui Toatsu Chemical (Tokyo, Japan) |

|

Polycaprolactone (PCL) |

CapaR | Solvay Group (Brussels, Belgium) | |

| Poly(butylene succinate-co-butylene adipate) (PBSA) | Bionolle | Showa Highpolymer (Tokyo, Japan) | |

Poly (butylene succinate) (PBS)  |

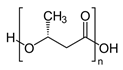

1.1.1. Biodegradable Polymers Produced by Bacteria

Some polyesters and polysaccharides accumulate in bacteria as a source of intracellular energy and carbon [9][11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21]. Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) are biodegradable aliphatic polyesters formed entirely through bacterial fermentation. Alcaligenes eutrophus has been extensively studied due to its capacity to generate vast volumes of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) (PHB). PHB accumulation in A. eutrophus can be controlled by changing the types or concentrations of carbon and nitrogen sources. For example, A. eutrophus produced PHB at more than 80% of the dry weight upon culture in a medium with an abundance of carbon sources, such as glucose, and low amounts of nitrogen sources.

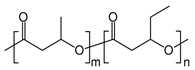

In general, the brittleness of PHB, which is caused by its high crystallinity, has limited its application on the industrial scale. Various copolymers, such as 3-hydroxyvalerate (3HV) units, are frequently incorporated into the polymer chain through bacterial fermentation to increase its toughness and flexibility. Because of its great biocompatibility and non-toxicity, the resultant copolymer of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) (P(HB-co-HV)) is employed to create internal sutures in the biomedical industry [8][22].

Gellan gum and curdlan are biodegradable polysaccharides produced by bacteria. They have mainly been utilized as food additives, especially gelling and thickening agents, owing to their high water absorbency and nontoxicity [9][23]. Edible films using gellan gum and curdlan have recently been developed and used as for food wrapping owing to their high water vapor permeability [24].

1.1.2. Biodegradable Polymers Produced from Natural Products and Their Derivatives

Despite the fact that chitin is one of the most prevalent natural compounds after cellulose, its low solubility and reactivity have restricted its industrial and commercial applicability. To solve this problem, chitin has been chemically modified by grafting with synthetic polymers to improve its miscibility with various commodity polymer [9]. Aoi et al. synthesized chitin derivatives containing polyoxazoline side chains and prepared miscible blends containing synthetic polymers, such as polyvinyl chloride and polyvinyl alcohol. These blends are widely used as new polymetric materials not only for their biodegradability but also for their moulding and mechanical properties, which are akin to those of commodity polymers [25].

In addition, PHB has also been produced using the leaves of transgenic plants such as Arabidopsis thaliana. This plant-mediated synthesis was justified by its potential production on a greater scale [26] at a lesser cost than microbial fermentation. As reported by Proirer et al., only the first enzyme necessary for PHB production from acetyl-CoA, 3-khetotiolase, is endogenously present in plants. A. eutrophus genes encoding acetoacetyl-CoA reductase and PHA synthase were expressed in transgenic A. thaliana to accomplish the PHB synthesis pathway in plants [27]. Bohmert-Tatarev et al. patented the methods of stable, fertile, and high PHA production in plants [28].

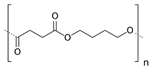

1.1.3. Biodegradable Polymers Produced via Chemical Synthesis

This group mainly consists of polylactic acid (PLA), polyglycolic acid (PGA), polycaprolactone (PCL), poly(butylene succinate-co-butylene adipate) (PBSA), and other aliphatic polyesters. These polymers are synthesized commonly through ring-opening polymerization accelerated by metals (ROP) or the polycondensation of their corresponding petroleum-derived monomers [9][29]. Among these polymers, PLA, which can be prepared from natural products, such as cereal- or sugarcane-based saccharides, as well as petroleum precursors, has attracted tremendous attention as a biopolymer with application potential [30][31]. Lactic acid that is obtained from glucose or sucrose via lactobacillus fermentation is polymerized by ROP after dimerization or direct polycondensation [8]. PLA typically shows a high rigidity, making it a suitable replacement for polystyrene and polyethylene terephthalate (PET) in several applications, such as packaging and textiles [30].

The biodegradability of commodity synthetic polymers can be increased by blending them with several types of natural products, such as starch and chitin. Ratto et al. prepared films from a poly(butylene succinate/adipate) (PBSA)/starch composite and investigated the processability and biodegradability of the resulting films, along with their mechanical and thermal properties. The biodegradable PBSA/starch film exhibited sufficient mechanical properties for plastic extrusion applications [32].

Similarly, PBS, which is created by polycondensing 1,4-butandiol and succinic acid, has found usage in a broad range of applications because its physical qualities are similar to the properties of commercially available polymers, such as polypropylene (PP) and polyethylene (PE). Additionally, monomers such as butylene adipate units are typically added into PBS polymer chains to enhance their strength and elasticity. The resulting copolyester, viz., PBSA, has also found several uses, such as agricultural and construction materials [32].

As mentioned above, various types of biodegradable polymers are utilized in numerous fields ranging from agricultural to biomedical applications. As citizens become more conscious of the importance of waste disposal and ecological preservation, biodegradable polymer usage is expected to increase and eventually replace the current commodity polymetric materials in practical use. The synthesis and/or modification of biodegradable polymers with improved mechanical and physical features have also piqued the attention of researchers. In the foreseeable future, the effective production of polymers exhibiting improved properties at reduced costs may become more crucial for realizing a sustainable society. Various initiatives have been proposed to lower the manufacturing costs of biopolymers, among which is a method based on utilizing industrial by-products such as molasses, waste glycerol, and banana frond extract [33][34][35][36][37][38][39].

1.2. Biodegradation Conditions

It is vital to understand the mechanisms and kinetics of polymer degradation in various natural and controlled settings in order to predict polymer degradation behaviour in dynamic environments [40]. Researchers are enthusiastically engaging in the biodegradation research of polymers in a variety of natural and controlled settings. Soil, mangrove wetlands, seas, rivers, anaerobic sludge, activated sludge, and aerobic or anaerobic compost are examples of natural settings [41][42][43][44]. The biodegradation test is also performed in vivo and in vitro to investigate the material’s biocompatibility property, for example, in phosphate buffer, blood serum, human blood, and animal muscle tissue [45][46]. After the complete biodegradation of polymers under aerobic conditions, the end products are carbon dioxide and water, whilst methane is the end product under anaerobic conditions [41].

Several variables influence polymer biodegradability, viz., climate, soil/water characteristics (humidity, temperature, pH, oxygen and nutrient levels), the indigenous microorganism consortia in the setting, and physiochemical qualities (surface area, chemical composition, polydispersity index, molecular weight, crystallinity) [41][47][48][49][50][51][52][53][54][55][56][57][58].

2. Physical Methods

Physical methods entail the physical observation of polymers and their surface micro-morphology, strength qualities, and weight reduction. Table 2 delineates the summarization of numerous methods to assess the biodegradation of polymers in various experimental settings, together with their advantages and limitations.

2.1. Physical Observations

Electron microscopy, such as scan electron microscopy (SEM), enables the observation of surface deterioration [59], whilst transmission electron microscopy (TEM) is widely used to observe the ultrathin cross-section of polymeric samples [60]. For example, PHA biodegradation, or bioerosion, is triggered on the polymer’s surface by PHA depolymerase. This qualitative examination enables the visible physical observation of the polymer’s hole, coarse, and porosity texture, which encourages bacterial attachment and leads to PHA depolymerase secretion [61][62]. The large size of the porous surface area occurs as a result of the microorganism’s reaction and, therefore, can be interpreted as the degree of biodegradation.

An experimental investigation was conducted by Adamcova et al. to visually monitor the microstructure and morphology of seven commercial packaging bioplastics (starch, polycaprolactone, natural material, cellulose, some material compositions that are not stated, etc.) and one petrochemical plastic claimed to be biodegradable (high-density polyethylene with totally degradable plastic additives, HDPE + TDPA) throughout a soil compost test for 12 weeks. The three samples with additives, including HDPE + TDPA, and samples with unknown material compositions did not indicate any visual signs of degradation and no colour changes in contrast to four samples that portrayed significant erosion, breaches, fractures, and holes on the surface when analysed by SEM [61].

2.2. Strength Properties

A high-precision tool called an extensometer is specially created to elucidate the strength properties of polymeric materials, such as the tensile strength, yield strength, yield point elongation, and strain ratio. Tensile strength can be defined as the highest stress that a polymeric plastic material can sustain while being stretched before breaking [63]. The tensile strength will decrease as the biodegradation process progresses and can be measured using an extensometer [64].

An extensometer is not only a tool for the elucidation of polymer deterioration/degradation but can also be applied to monitor the viscoelasticity of newly ameliorated polymers. Morreale et al. employed a commercial biopolymer produced by FKuR Kunststoff GmbH (Willich, Germany), with the trade name of BioFlex F2110, which is based on a blend of PLA and thermoplastic-copolyesters, and then the authors modified it by adding wood flour. These composites were then subjected to a viscoelasticity test at 60 °C using an oven outfitted with four extensometers directly attached to movable clamps and weight holders of 1.5 MPa. The acquired results were plotted against time and demonstrated that the addition of wood flour improved the rigidity and viscoelasticity resistance by 0.6% when compared to the pristine polymer, without compromising other parameters, such as the tensile strength [65].

Table 2. Summarization of numerous methods to assess the biodegradation of polymers in various experimental settings, together with their advantages and limitations.

| No. | Test Material | Brief Description, Aim, and Degradation Condition |

Advantages or Limitation | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical methods | ||||

| 1 | PHBHHx/PBAT (80/20) | TEM: To analyse the cross-section of the sheet. SEM: To analyse the surface morphology of the melt blend sheet. Ruthenium tetroxide (RuO4) is used as a staining agent. Condition: Seawater for 28 days with 42% biodegradation. |

TEM: The PBAT region darkens owing to the lower permeability of the electron beam through the attachment of RuO4 to the phenyl group in the PBAT as compared with the PHBHHx region, allowing for clear observation. | [60] |

| 2 | PHB, P(HB-co-12%-HHx) |

SEM: To analyse the surface morphology. Conditions: Activated sludge for 18 days with a 0.65% recovery weight. |

SEM: Able to observe the porous and rough surface, indicating fast degradation, also contributing to the low degree of crystallinity of HHx. | [62] |

| Chromatographic methods | ||||

| 3 | P(HB-co-HHx) films. | Thermally assisted hydrolysis and methylation–gas chromatography (THM-GC): Rapid analysis of the copolymer composition during biodegradation. Condition: Farm soil pH 5.3 for 28 days at 34 °C with 1.91% recovery weight. |

THM-GC: Able to observe the local biodegradation behaviour of the degraded films based on the changes in the copolymer composition. | [44] |

| 4 | Intracellular P(HB-co-HV) in Ralstonia eutropha and recombinant Escherichia coli. | Py-GC-MS: Rapid analysis of PHA contents and their monomer compositions accumulated intracellularly | Py-GC-MS: Promising tool used to rapidly screen PHA-containing strains based on polymer contents, along with their monomer compositions. The data obtained by this method indicate results similar to those of conventional GC-FID. | [66] |

| 5 | Whole bacterial cells of Cupriavidus necator accumulating P(HB-co-HV). | THM-GC in the presence of TMAH: Rapid and direct compositional analysis of P(HB-co-HV) in whole cells. | THM-GC in the presence of TMAH: Chromatograms clearly indicate peaks derived from the HB and HV units of the polymer chains without any interference by the bacterial matrix components and no cumbersome sample pre-treatment required. The data obtained by this method indicate results similar to those of conventional GC-FID. | [67] |

| Spectroscopic methods | ||||

| 6 | Extracted PHAs from bacteria cells such as E. coli and Pseudomonas sp. | NMR: To characterize PHAs. FTIR: To investigate functional groups of the PHAs. |

FTIR data indicate the presence of hydroxyoctaoate, medium-chain-length PHAs and hydroxydecanoate with strong bands at 1631 cm−1, 1548 cm−1, and 1409 cm−1. NMR spectra show the presence of interconnection functional groups of HC=CH bonds at 3.363 ppm and CH2O-COOH bonds at 2.548 ppm. Both methods require a sample extraction process prior to each analysis. | [68] |

| 7 | Bioplastics from starch/chitosan reinforced with PP. | FTIR: To investigate functional groups of the bioplastics. The spectra portray main bonds of O-H hydrogen bonds (carboxylic acid), C-H alkanes, C=C alkenes, and C-O alcohols. | FTIR spectrum indicates that the functional groups of bioplastics have similarity with their constituent components. Sample extraction process is required. | [69] |

| 8 | Bioplastics from starch/chitosan reinforced with PP. | XRD: To analyse the degree of crystallinity. | The XRD data evince that the biopolymer had an amorphous crystalline structure, with the major wide peaks located between 18° and 30°. | [69] |

| 9 | Single-use bioplastics (SUPs). | XRF: To determine the elemental composition and concentration in the SUPs. | Most of the SUPs exceed the standard values, and the highest concentrations of Cu, Cr, Mo, Zn, Fe, and Pb were 1898 mg/kg, 1586 mg/kg, 95 mg/kg, 1492 mg/kg, 1900 mg/kg, and 7528 mg/kg. XRF is a non-destructive analytical method which enables the same sample to be used again for further analysis. | [70] |

| Respirometric methods | ||||

| 10 | PHBHHx/PBAT (80/20). | BOD tester: To measure biodegradation induced by the microbial metabolism. Condition: Seawater for 28 days with 42% biodegradation. |

The seawater was placed together with samples in a fermenter, and the amount of consumed oxygen (O2) gas was measured. This method is an indirect measurement of O2 that has been utilized for complete sample degradation, which may carry some errors. It is preferable to cross-check the results with the weight loss data. | [60] |

| Meta-analysis | ||||

| 11 | PHAs | Statistical analysis: To estimate the PHA mean biodegradation rate and lifetime. Condition: Seawater | The statistical analysis enables the estimation of the biodegradation of PHA in the seawater as 0.04–0.09 mg/day/cm. | [71] |

| Thermal methods | ||||

| 12 | Poly(butylene succinate-co-butylene adipate) film sample | DSC: To determine the degree of crystallinity. | The obtained degree of crystallinity of the original and heated film samples were 46.1 and 42.4%, respectively, evinced the crystallinity of the PBSA film, which was considerably lower for the heat-treated film. | [48] |

| 13 | PHAs accumulated in Pseudomonas putida | DSC and TGA: To analyse the thermal properties. | Thermal properties indicate that the accumulated PHA is semi-crystalline, with a good thermal stability, Td of 264.6 to 318.8 °C, Tm of 43 °C, Tg of −1.0 °C, and ΔHf of 100.9 J/g. Requires sample pre-treatment of PHA extraction. | [72] |

2.3. Mass Reduction

Measuring the weight loss is the simplest practical, direct, and widely used method of quantifying the biodegradation activity of any polymeric material using an analytical balance. Baidurah et al. conducted a soil burial degradation test within 28 days to elucidate the degradation mechanisms of poly(butylene succinate-co-butylene adipate) (PBSA) thin film samples with a ratio of 82.2:17.8. After each designated period of 7, 14, 21, and 28 days, the deteriorated PBSA films were cleaned, dried, and weighed. The recovery (weight %) of each deteriorated film was obtained by dividing its dry weight by the weight of the original film prior to the burial test. Upon 28 days of the soil burial degradation test, the recovery weight of the material was reduced to 68.1% [73]. Researchers should bear in mind that, when using this method, the mass reduction should be calculated by deducting the weight of the original sample prior to the degradation test.

Due to the fact that weight loss measurements are difficult to extrapolate, it is preferable to complement this approach with other analytical methods, such as respirometric methods, FTIR, and NMR [49]. In a separate study by Salomez et al., the authors conducted both experiments of the weight loss and respirometric methods simultaneously to compare the degradation of two samples, viz., P(HB-co-HV) and PBSA. In the respirometric analysis, the carbon dioxide released by the materials during their degradation were recorded. Upon 450 days of incubation, they reported that the P(HB-co-HV) and PBSA polymers had degraded, with weight losses of 5.5 and 8.0%, respectively. The authors emphasized that the polymer’s weight loss does not ensure its eventual absorption by microorganisms, as demonstrated by respirometry analysis [74].

References

- Ichikawa, Y.; Mizukoshi, T. Bionolle (Polybutylene succinate). Adv. Polym. Sci. 2012, 245, 285–314.

- Alam, O.; Billah, M.; Yajie, D. Characteristics of plastic bags and their potential environmental hazards. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 132, 121–129.

- Dilli, R. Comparison of Existing Life Cycle Analysis of Shopping Bag Alternatives; Final Report; Hyder Consulting Pty Ltd.: Melbourne, Australia, 2007.

- Finzi-Quintão, C.M.; Novack, K.M.; Bernardes-Silva, A.C. Identification of biodegradable and oxo-biodegradable plastic bags samples composition. Macromol. Symp. 2016, 367, 9–17.

- Luijsterburg, B.; Goossens, H. Assessment of plastic packaging waste: Material origin, methods, properties. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2014, 85, 88–97.

- Markowicz, F.; Szymańska-Pulikowska, A. Analysis of the possibility of environmental pollution by composted biodegradable and oxo-biodegradable plastics. Geosciences 2019, 9, 460.

- Portillo, F.; Yashchuk, O.; Hermida, É. Evaluation of the rate of abiotic and biotic degradation of oxo-degradable polyethylene. Polym. Test 2016, 53, 58–69.

- Boey, J.Y.; Mohamad, L.; Khok, Y.S.; Tay, G.S.; Baidurah, S. A review of the applications and biodegradation of polyhydroxyalkanoates and poly(lactic acid) and its composites. Polymers 2021, 13, 1–21.

- Zhang, Z.; Ortiz, O.; Goyal, R.; Kohn, J. Biodegradable polymers. Plast. Des. Libr. 2014, 13, 303–335.

- Flieger, M.; Kantorova, M.; Prell, A.; Rezanka, T.; Votruba, J. Biodegradable plastics from renewable sources. Folia Microbiol. 2003, 48, 27–44.

- Dalal, J.; Sarma, P.M.; Lavania, M.; Mandal, A.K.; Lal, B. Evaluation of bacterial strains isolated from oil-contaminated soil for production of polyhydroxyalkanoic acids (PHA). Pedobiologia 2010, 54, 25–30.

- Allen, A.D.; Anderson, W.A.; Ayorinde, F.O.; Eribo, B.E. Biosynthesis and characterization of copolymer poly (3HB-co-3HV) from saponified Jatropha curcas oil by Pseudomonas oleovorans. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 37, 849–856.

- Elbahloul, Y.; Steinbuchel, A. Large-scale production of poly (3-hydroxyoctanoic acid) by Pseudomonas putida GPo1 and a simplified downstream process. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 643–651.

- Vishnuvardhan Reddy, S.; Thirumala, M.; Mahmood, S. Production of PHB and P (3HB-co-3HV) biopolymers by Bacillus megaterium strain OU303A isolated from municipal sewage sludge. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009, 25, 391–397.

- Ni, Y.-Y.; Kim, D.Y.; Chung, M.G.; Lee, S.H.; Park, H.-Y.; Rhee, Y.H. Biosynthesis of medium-chain-length poly(3-hydroxyalkanoates) by volatile aromatic hydrocarbons-degrading Pseudomonas fulva TY16. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 8485–8488.

- López-Cuellar, M.; Alba-Flores, J.; Rodríguez, J.; Pérez-Guevara, F. Production of polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) with canola oil as carbon source. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2011, 48, 74–80.

- Huijberts, G.; Eggink, G.; de Waard, P.; Huisman, G.W.; Witholt, B. Pseudomonas putida KT2442 cultivated on glucose accumulates poly (3-hydroxyalkanoates) consisting of saturated and unsaturated monomers. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1992, 58, 536–544.

- Matsusaki, H.; Abe, H.; Doi, Y. Biosynthesis and properties of poly (3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyalkanoates) by recombinant strains of Pseudomonas sp. 61–3. Biomacromolecules 2000, 1, 17–22.

- Choi, S.Y.; Rhie, M.N.; Kim, H.T.; Joo, J.C.; Cho, I.J.; Son, J.; Jo, S.Y.; Sohn, Y.J.; Baritugo, K.A.; Pyo, J.; et al. Metabolic engineering for the synthesis of polyesters: A 100-year journey from polyhydroxyalkanoates to non-natural microbial polyesters. Metab. Eng. 2020, 58, 47–81.

- Madison, L.L.; Huisman, G.W. Metabolic engineering of poly (3-hydroxyalkanoates): From DNA to plastic. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 1999, 63, 21–53.

- Shon, Y.J.; Kim, H.T.; Jo, S.Y.; Song, H.M.; Baritugo, K.A.; Pyo, J.; Choi, J.; Joo, J.C.; Park, S.J. Recent advances in systems metabolic engineering strategies for the production of biopolymers. Biotechol. Bioprocess. Eng. 2020, 25, 848–861.

- Wei, Y.H.; Chen, W.C.; Huang, C.K.; Wu, H.S.; Sun, Y.M.; Lo, C.H. Janarthanan Screening and evaluation of Polyhydroxybutyrate-Producing strains from indigenous isolate Cupriavidus taiwanensis strains. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011, 12, 252–265.

- Marubayashi, H.; Yukinaka, K.; Enomoto-Rogers, Y.; Takemura, A.; Iwata, T. Curdlan ester derivatives: Synthesis, structure, and properties. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 103, 427–433.

- Xiao, G.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, L.; You, Q.; Hao, P.; You, Y. Production and storage of edible film using gellan gum. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2011, 8, 756–763.

- Aoi, K.; Takasu, A.; Okada, M. New chitin-based polymer hybrids, miscibility of poly(vinyl alcohol) with chitin derivatives. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 1995, 16, 757–761.

- Thomson, N.; Roy, I.; Summers, D.; Sivaniah, E. In vitro production of polyhydroxyalkanoates: Achievements and applications. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2010, 85, 760–767.

- Proirer, Y. Production of polyesters in transgenic plants. Adv. Biochem. Eng./Biotechnol. 2001, 71, 209–240.

- Bohmert-Tatarev, K.; Mcavoy, S.; Peoples, O.P.; Snell, K.D. Stable, Fertile, High Polyhydroxyalkanoate Producing Plants and Methods of Producing Them. U.S. Patent App. 20,100/229,258, 4 August 2015.

- Bonduelle, C.; Martin-Vaca, B.; Bourissou, D. Lipase-catalyzed ring-opening polymerization of the O-carboxylic anhydride derived from lactic acid. Biomacromolecules 2009, 10, 3069–3073.

- Siegenthaler, K.O.; Kunkel, A.; Skupin, G.; Yamamoto, M. Ecoflex® and Ecovio®: Biodegradable, Performance-Enabling Plastics. Adv. Polym. Sci. 2012, 245, 91–136.

- Baidurah, S.; Kobayashi, T.; Aziz, A.A. PLA Based Plastics for Enhanced Sustainability of the Environment. Encycl. Mater. Plast. Polym. 2021, 2, 511–519.

- Ratto, J.A.; Stenhoose, P.J.; Auerbach, M.; Mitchell, J.; Farrell, R. Processing, performance and biodegradability of a thermoplastic aliphatic polyester/starch system. Polymer 1999, 40, 6777–6788.

- Boey, J.Y.; Baidurah, S.; Tay, G.S. A review on the enhancement of composite’s interface properties through biological treatment of natural fibre/lignocellulosic material. Polym. Polym. Compos. 2022, 30, 1–15.

- Kassim, M.A.; Meng, T.K.; Serri, N.A.; Yusoff, S.B.; Shahrin, N.A.M.; Seng, K.Y.; Bakar, M.H.A.; Keong, L.C. Sustainable biorefinery concept for industrial bioprocessing. In Biorefinery Production Technologies for Chemicals and Energy, 1st ed.; Kulia, A., Mukhopadhyay, Eds.; Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA; Scrivener Publishing LLC: Beverly, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 15–39.

- Low, T.J.; Mohammad, S.; Sudesh, K.; Baidurah, S. Utilization of banana (Musa sp.) fronds extract as an alternative carbon source for poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) production by Cupriavidus necator H16. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2021, 34, 102048.

- Mohamad, L.; Hasan, H.A.; Sudesh, K.; Baidurah, S. Dual application of black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens): Protein-rich animal feed and biological extraction agent for polyhydroxybutyrate. Malays. J. Microbiol. 2021, 17, 624–634.

- Sen, K.Y.; Hussin, M.H.; Baidurah, S. Biosynthesis of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) (PHB) by Cupriavidus necator from various pretreated molasses as carbon source. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2019, 17, 51–59.

- Sen, K.Y.; Baidurah, S. Renewable biomass feedstocks for production of sustainable biodegradable polymer. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2021, 27, 100412.

- Wendy, Y.B.D.; Fauziah, M.Z.N.; Baidurah, S.; Tong, W.Y.; Lee, C.K. Production and characterization of polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) BY Burkholderia cepacia BPT1213 using waste glycerol as carbon source. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2022, 41, 102310.

- Volova, T.G.; Boyandin, A.N.; Vasiliev, A.D.; Karpov, V.A.; Prudnikova, S.V.; Mishukova, O.V.; Boyarskikh, U.A.; Filipenko, M.L.; Rudnev, V.P.; Xuân, B.B.; et al. Biodegradation of polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) in tropical coastal waters and identification of PHA-degrading bacteria. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2010, 95, 2350–2359.

- Muhammadi, S.; Afzal, M.; Hameed, S. Bacterial polyhydroxyalkanoates-eco-friendly next generation plastic: Production, biocompatibility, biodegradation, physical properties and applications. Green Chem. Lett. Rev. 2015, 8, 56–77.

- Sridewi, N.; Bhubalan, K.; Sudesh, K. Degradation of commercially important polyhydroxyalkanoates in tropical mangrove ecosystem. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2006, 91, 2931–2940.

- Wang, S.; Lydon, K.A.; White, E.M.; Grubbs, J.B.; Lipp, E.K.; Locklin, J.; Jambeck, J.R. Biodegradation of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) plastic under anaerobic sludge and aerobic seawater conditions: Gas evolution and microbial diversity. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 5700–5709.

- Baidurah, S.; Murugan, P.; Sen, K.Y.; Furuyama, Y.; Nonome, M.; Sudesh, K.; Ishida, Y. Evaluation of soil burial biodegradation behaviour of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) on the basis of change in copolymer composition monitored by thermally assisted hydrolysis and methylation-gas chromatography. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2019, 137, 146–150.

- Qu, X.H.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, K.Y.; Chen, G.Q. In vivo studies of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) based polymers: Biodegradation and tissue reactions. Biomaterials 2006, 27, 3540–3548.

- Shishatskaya, E.I.; Volova, T.G.; Gordeev, S.A.; Puzyr, A.P. Degradation of P(3HB) and P(3HB-co-3HV) in biological media. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2005, 16, 643–657.

- Numata, K.; Abe, H.; Iwata, T. Biodegradability of poly(hydroxyalkanoate) materials. Materials 2009, 2, 1104–1126.

- Baidurah, S.; Takada, S.; Shimizu, K.; Ishida, Y.; Yamane, T.; Ohtani, H. Evaluation of biodegradation behavior of poly(butylene succinate-co-butylene adipate) with lowered crystallinity by thermally assisted hydrolysis and methylation-gas chromatography. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2013, 103, 73–77.

- Chamas, A.; Moon, H.; Zheng, J.; Qiu, Y.; Tabassum, T.; Jang, J.H.; Abu-Omar, M.; Scott, S.L.; Suh, S. Degradation rates of plastics in the environment. ACS Sus. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 3494–3511.

- Wierckx, N.; Narancic, T.; Eberlein, C.; Wei, R.; Drzyzga, O.; Magnin, A.; Ballerstedt, H.; Kenny, S.T.; Pollet, E.; Avérous, L. Plastic biodegradation: Challenges and opportunities. In Consequences of Microbial Interactions With Hydrocarbons, Oils, and Lipids: Biodegradation and Bioremediation; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 1–29.

- Andrady, A.L. Assessment of environmental biodegradation of synthetic polymers. J. Macromol. Sci. Part C Polym. Rev. 1994, 34, 25–76.

- Brandl, H.; Puchner, P. Biodegradation of plastic bottles made from “biopol” in an aquatic ecosystem under in situ conditions. Biodegradation 1992, 2, 237–243.

- Chinaglia, S.; Tosin, M.; Degli-Innocenti, F. Biodegradation rate of biodegradable plastics at molecular level. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2018, 147, 237–244.

- Follain, N.; Chappey, C.; Dargent, E.; Chivrac, F.; Crétois, R.; Marais, S. Structure and barrier properties of biodegradable polyhydroxyalkanoate films. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 6165–6177.

- Gewert, B.; Plassmann, M.M.; Macleod, M. Pathways for degradation of plastic polymers floating in the marine environment. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 2015, 17, 1513–1521.

- Gu, J.D. Microbiological deterioration and degradation of synthetic polymeric materials: Recent research advances. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2003, 52, 69–91.

- Guerin, P.; Renard, E.; Langlois, V. Degradation of natural and artificial polys: From biodegradation to hydrolysis. In Plastics from Bacteria: Natural Functions and Applications. Microbiology Monographs; Chen, G.-Q., Ed.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2010; pp. 283–321.

- Accinelli, C.; Saccà, M.L.; Mencarelli, M.; Vicari, A. Deterioration of bioplastic carrier bags in the environment and assessment of a new recycling alternative. Chemosphere 2012, 89, 136–143.

- Greene, J. PLA and PHA Biodegradation in the Marine Environment; Department of Resources Recycling and Recovery: Sacramento, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 1–38.

- Sashiwa, H.; Fukuda, R.; Okura, T.; Sato, S.; Nakayama, A. Microbial degradation behaviour in seawater of polyester blends containing poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) (PHBHHx). Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 1–11.

- Adamcova, D.; Radziemska, M.; Zloch, J.; Dvořáčková, H.; Elbl, J.; Kynický, J.; Brtnický, M.; Vaverková, M.D. SEM analysis and degradation behavior of conventional and bio-based plastics during composting. Acta Univ. Agric. Silvic. Mendel. Brun. 2018, 66, 349–356.

- Wang, Y.-W.; Mo, W.; Yao, H.; Wu, Q.; Chen, J.; Chen, G.-Q. Biodegradation studies of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate). Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2004, 85, 815–821.

- Chan, C.M.; Vandi, L.-J.; Pratt, S.; Halley, P.; Richardson, D.; Werker, A.; Laycock, B. Insights into the biodegradation of PHA/wood composites: Micro- and macroscopic changes. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2019, 21, e00099.

- Deroiné, M.; Le Duigou, A.; Corre, Y.-M.; Le Gac, P.-Y.; Davies, P.; César, G.; Bruzaud, S. Seawater accelerated ageing of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate). Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2014, 105, 237–247.

- Morreale, M.; Liga, A.; Mistretta, M.C.; Ascione, L.; Mantia, F.P.L.M. Mechanical, Thermomechanical and Reprocessing Behavior of Green Composites from Biodegradable Polymer and Wood Flour. Materials 2015, 28, 7536–7548.

- Khang, T.U.; Kim, M.J.; Yoo, J.I.; Sohn, Y.J.; Jeon, S.G.; Park, S.J.; Na, J.G. Rapid analysis of polyhydroxyalkanoate contents and its monomer compositions by pyrolysis-gas chromatography combined with mass spectrometry (Py-GC/MS). Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 174, 449–456.

- Baidurah, S.; Kubo, Y.; Kuno, M.; Kodera, K.; Ishida, Y.; Yamane, T.; Ohtani, H. Rapid and direct compositional analysis of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) in whole bacterial cells by thermally assisted hydrolysis and methylation-gas chromatography. Anal. Sci. 2015, 31, 79–83.

- Narayanan, M.; Kumarasamy, S.; Ranganathan, M.; Kandasamy, S.; Kandasamy, G.; Gnanavel, K.; Mamtha, K. Production and characterization of polyhydroxyalkanoates synthesized by E. coli isolated from sludge soil. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 33, 3646–3653.

- Jangong, O.S.; Gareso, P.L.; Mutmainna, I.; Tahir, D. Fabrication and characterization starch/chitosan reinforced polypropylene as biodegradable. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1341, 082022.

- Shruti, V.C.; Perez-Guevara, F.; Roy, P.D.; Elizalde-Martinez, I.; Kutralam-Muniasamy, G. Identification and characterization of single use oxo/biodegradable plastics from Mexico City, Mexico: Is the advertised labeling useful? Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 739, 140358.

- Dilkes-Hoffman, L.S.; Lant, P.A.; Laycock, B.; Pratt, S. The rate of biodegradation of PHA bioplastics in the marine environment: A meta-study. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 142, 15–24.

- Gumel, A.H.; Annuar, M.S.M.; Heidelber, T. Biosynthesis and Characterization of Polyhydroxyalkanoates Copolymers Produced by Pseudomonas putida Bet001 Isolated from Palm Oil Mill Effluent. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e45214.

- Baidurah, S.; Takada, S.; Shimizu, K.; Yasue, K.; Arimoto, S.; Ishida, Y.; Yamane, T.; Ohtani, H. Evaluation of Biodegradability of Poly(butylene succinate-co-butylene adipate) on the basis of copolymer composition determined by thermally assisted hydrolysis and methylation-gas chromatography. Int. J. Polym. Anal. Charact. 2012, 17, 29–37.

- Salomez, M.; George, M.; Fabre, P.; Touchaleaume, F.; Cesar, G.; Lajarrige, A.; Gastaldi, E. A comparative study of degradation mechanisms of PHBV and PBSA under laboratory-scale composting conditions. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2019, 167, 102–113.

More

Information

Subjects:

Biotechnology & Applied Microbiology

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.5K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

14 Dec 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No