Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cátia Barra | -- | 1116 | 2022-12-12 01:26:45 | | | |

| 2 | Conner Chen | Meta information modification | 1116 | 2022-12-12 11:21:19 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Magalhães, A.; Barra, C.; Borges, A.; Santos, L. Circadian Rhythm Influences Insulin Secretion. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/38508 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Magalhães A, Barra C, Borges A, Santos L. Circadian Rhythm Influences Insulin Secretion. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/38508. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Magalhães, Ana, Cátia Barra, Ana Borges, Lèlita Santos. "Circadian Rhythm Influences Insulin Secretion" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/38508 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Magalhães, A., Barra, C., Borges, A., & Santos, L. (2022, December 12). Circadian Rhythm Influences Insulin Secretion. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/38508

Magalhães, Ana, et al. "Circadian Rhythm Influences Insulin Secretion." Encyclopedia. Web. 12 December, 2022.

Copy Citation

In the intestine, the expression of sodium-glucose transport protein 1 (SGLT-1) has a rhythmic cycle, which is increased when the glucose intake is anticipated. Similar mechanisms regulate insulin secretion. Besides being regulated by glucose levels and incretins, its exocytosis also has a circadian regulation, possibly because incretins also have a circadian rhythm themselves.

daily insulin fluctuation

insulin sensitivity

diets

1. Introduction

Insulin was discovered by Frederick Banting and Charles Best in 1921. It is a pancreatic beta-cell anabolic hormone initially produced by as pre-insulin and then as proinsulin after a maturation process [1]. Subsequently, it is translocated from the endoplasmic reticulum to the Golgi apparatus, where it is cleaved into C-peptide and insulin, which are simultaneously released by exocytosis [2]. Its production by pancreatic beta cells is enhanced in response to glucose, and it is responsible for maintaining constant blood levels of glucose and metabolic homeostasis. However, it has been demonstrated that amino acids and fatty acids are also capable of stimulating insulin secretion [3][4]. Its secretion from pancreatic beta cells is biphasic: the first phase occurs with a rapid release, while the second phase is characterized by a more sustained and less elevated release [5]. Insulin levels are increased in the postprandial period when the circulating glucose levels increase, making the first phase very significant. In this phase, insulin inhibits glucagon secretion from the pancreatic alpha cells through paracrine action at the beginning of the meal. On the other hand, the second phase is critical for maintaining this inhibition and increasing glucose storage and utilization [6]. Thirty minutes after the beginning of the meal, insulin suppresses lipolysis in the adipose tissue by inactivating the hormone-sensitive lipase, leading to a decrease in non-esterified fatty acids (NEFA) and glycerol in the blood [7][8]. The lower blood NEFA and higher insulin levels induce the suppression of glucose production in the liver and an increase in glucose utilization (glycolysis) by the muscle [3][9][10]. Insulin and glucagon secretion, as well as glucose homeostasis, are also regulated by the incretins, which are secreted by the gut in response to food intake [11][12]. Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) are the two major incretins derived from gut neuroendocrine cells and are involved in these mechanisms, and their receptors may be found both in alpha and beta cells [11][13].

Insulin secretion dysregulation due to several causes promotes the development of diabetes. Type 1 diabetes (T1D) is characterized by auto-immune destruction of beta cells, while type 2 diabetes (T2D) is related to the development of insulin resistance, which is associated with obesity and metabolic syndrome. In T2D, beta-cell destruction is also observed through their progressive exhaustion and dysfunction in a later phase [14][15]. Consequently, beta-cell hyperplasia and a hyperinsulinemic state are often observed in obese patients in order to compensate for chronic low-grade inflammation and insulin resistance [14][16][17]. Moreover, hyperinsulinemia itself contributes to insulin resistance due to insulin receptor downregulation [11]. Lifestyle changes such as an equilibrated diet and physical exercise may prevent these events and thus contribute to maintaining a normal weight and insulin sensitivity in the peripheral tissues.

2. Circadian Rhythm Influences Insulin Secretion

The circadian rhythm is essential for maintaining a normal body physiology. It is mediated by specific components that are controlled by the daily light–dark and feeding–fasting cycles. The central nervous system plays an important role in the circadian rhythm through synapse networking, which acts in different brain regions and in endocrine cells, contributing to the circadian regulation of metabolism [18]. These outputs are integrated into the hypothalamus, which is responsible for hunger–satiety, thermoregulation, sleep–arousal, and osmolarity [19].

The metabolic activity of several organs is also mediated by their internal clocks and circadian rhythms. In the intestine, the expression of sodium-glucose transport protein 1 (SGLT-1) has a rhythmic cycle, which is increased when the glucose intake is anticipated. Similar mechanisms regulate insulin secretion. Besides being regulated by glucose levels and incretins, its exocytosis also has a circadian regulation, possibly because incretins also have a circadian rhythm themselves [20]. Some studies in healthy human subjects have shown daily fluctuations in glucose tolerance, suggesting that it is greatest in the morning, while a significant decrease occurs during the night [21][22]. This is not only because of the oscillations in peripheral insulin sensitivity, but also the variations of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion during the daily 24 h period [23].

Uncoupling protein 2 (UCP2) has been described to influence metabolism, as it is expressed by endogenous circadian oscillators in pancreatic islets and acts in beta cells as a negative regulator of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS). As mentioned before, insulin regulates the metabolic response to fasting and its suppression is crucial to allow for endogenous glucose production in the liver and lipolysis in the adipose tissue in order to release metabolic fuel. Therefore, Ucp2/UCP2 has been suggested to coordinate insulin secretion according to nutrient ingestion, so an upregulation of Ucp2/UCP2 prevents hypoglycaemia during the fasting period by inhibiting insulin secretion and promoting fuel mobilization [24][25]. This type of regulation influences the activity of several other endocrine pathways such as melatonin, glucocorticoids, and growth hormone (GH) [20]. GH and cortisol secretion are regulated by their own circadian rhythm, and are higher in the nocturnal period, which contributes to insulin resistance in the early morning hours [22].

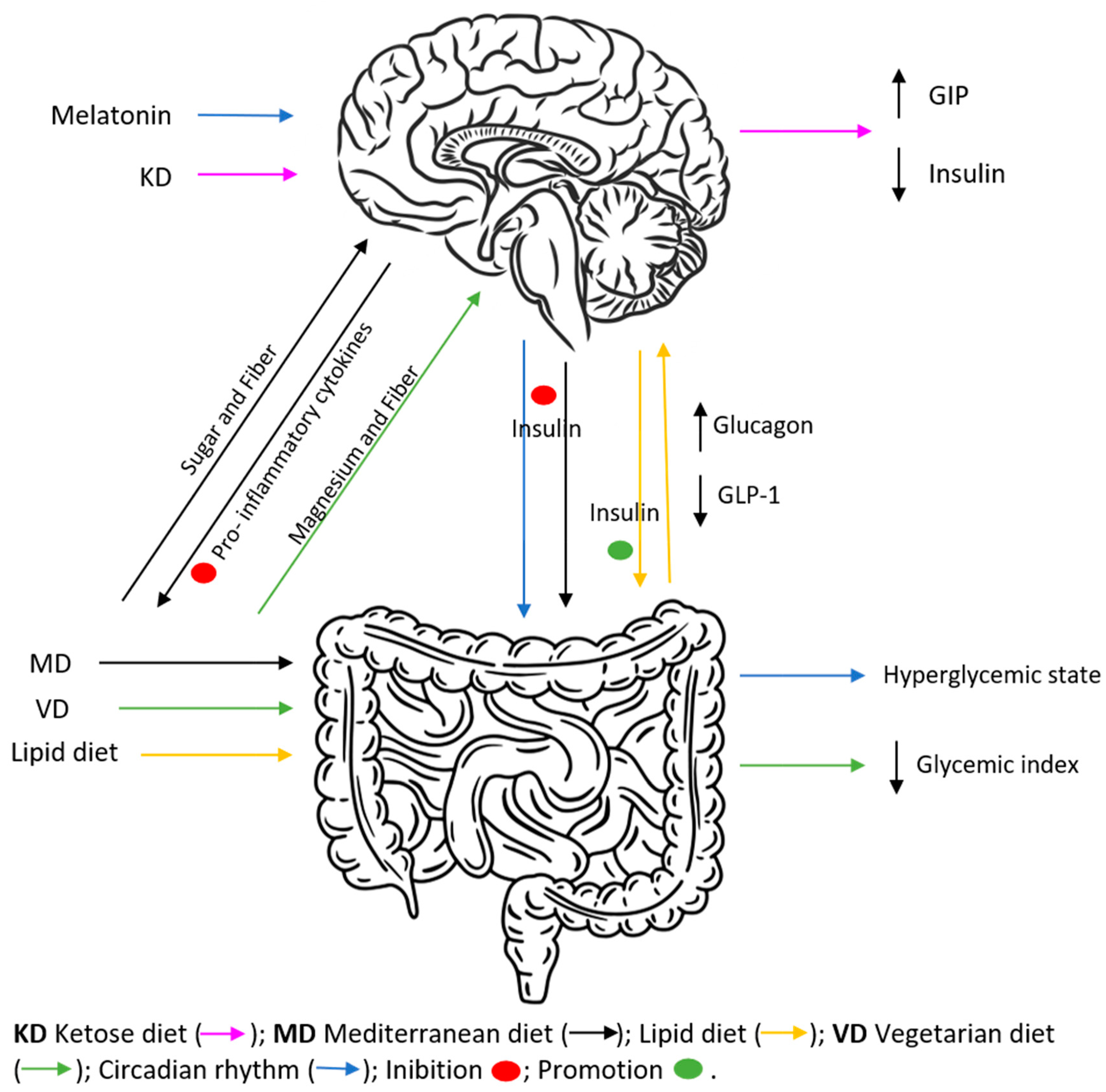

It has been demonstrated that chronic disruption of these circadian mechanisms is related to the development of metabolic diseases, as established by several studies in shift workers [26][27]. In a retrospective study conducted by Garaulet and her collaborators, eating early (lunch time before 15:00 p.m.) results in enhanced weight loss effectiveness, suggesting a relation between eating intervals and the day–night cycle in the metabolism [28]. Other studies have revealed that time-restricted feeding is capable of improving metabolic diseases due to sustained diurnal rhythms and imposing daily feeding–fasting cycles [29][30]. Similar to what happens with GH and cortisol, melatonin (Figure 1) also promotes a hyperglycaemic state in the evening, given that melatonin binding to its receptor in pancreatic islets inhibits insulin release from the beta cells [31]. Reciprocal interactions between metabolism and the circadian clock imply that nutrition quality, quantity, and daily eating patterns can affect diurnal rhythms, which in turn determine whole-body physiology.

Figure 1. Effects of different diets on insulin and incretins secretion, as well as hyperglycaemic and inflammatory states. KD, characterized by the ingestion of <50 g of carbohydrates/day, promotes a decrease in insulin and increase in glucagon and GIP fasting levels. MD, because of its higher fiber supply and reduced sugar ingestion, is capable of decreasing blood insulin levels and increasing GIP secretion, similarly decreasing pro-inflammatory cytokine activation and reducing the risk of diabetes development. VD, based on reduced calorie ingestion and being rich in magnesium and fibre, promotes a decrease in GI. A lipid diet is associated with diabetes development by increasing glucagon secretion and decreasing GLP-1.

References

- Bunney, P.E.; Zink, A.N.; Holm, A.A.; Billington, C.J.; Kotz, C.M. Orexin activation counteracts decreases in nonexercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT) caused by high-fat diet. Physiol. Behav. 2017, 176, 139–148.

- Fu, Z.; Gilbert, E.R.; Liu, D. Regulation of Insulin Synthesis and Secretion and Pancreatic Beta-Cell Dysfunction in Diabetes. Curr. Diabetes Rev. 2012, 9, 25–53.

- Dimitriadis, G.D.; Maratou, E.; Kountouri, A.; Board, M.; Lambadiari, V. Regulation of postabsorptive and postprandial glucose metabolism by insulin-dependent and insulin-independent mechanisms: An integrative approach. Nutrients 2021, 13, 159.

- Newsholme, P.; Cruzat, V.; Arfuso, F.; Keane, K. Nutrient regulation of insulin secretion and action. J. Endocrinol. 2014, 221, R105–R120.

- Seino, S.; Shibasaki, T.; Minami, K. Dynamics of insulin secretion in obesity. J. Clin. Investig. 2011, 121, 2118–2125.

- Steiner, K.E.; Mouton, S.M.; Bowles, C.R.; Williams, P.E.; Cherrington, A.D. The relative importance of first- and second-phase insulin secretion in countering the action of glucagon on glucose turnover in the conscious dog. Diabetes 1982, 31, 964–972.

- Miles, J.M.; Wooldridge, D.; Grellner, W.J.; Windsor, S.; Isley, W.L.; Klein, S.; Harris, W.S. Nocturnal and postprandial free fatty acid kinetics in normal and type 2 diabetic subjects: Effects of insulin sensitization therapy. Diabetes 2003, 52, 675–681.

- Dimitriadis, G.; Boutati, E.; Lambadiari, V.; Mitrou, P.; Maratou, E.; Brunel, P.; Raptis, S.A. Restoration of early insulin secretion after a meal in type 2 diabetes: Effects on lipid and glucose metabolism. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2004, 34, 490–497.

- Ferrannini, E.; Barrett, E.J.; Bevilacqua, S.; DeFronzo, R.A. Effect of fatty acids on glucose production and utilization in man. J. Clin. Investig. 1983, 72, 1737–1747.

- Groop, L.C.; Bonadonna, R.C.; DelPrato, S.; Ratheiser, K.; Zyck, K.; Ferrannini, E.; DeFronzo, R.A. Glucose and free fatty acid metabolism in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Evidence for multiple sites of insulin resistance. J. Clin. Investig. 1989, 84, 205–213.

- Boer, G.A.; Holst, J.J. Increatin Hormones and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus—Mechanistic Insights and Therapeutic Approches. Biology 2020, 9, 473.

- Nauck, M.A.; Meier, J.J. Incretin hormones: Their role in health and disease. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2018, 20, 5–21.

- Heller, R.S.; Kieffer, T.J.; Habener, J.F. Insulinotropic glucagon-like peptide I receptor expression in glucagon- producing α-cells of the rat endocrine pancreas. Diabetes 1997, 46, 785–791.

- Christensen, A.A.; Gannon, M. The Beta Cell in Type 2 Diabetes. Curr. Diab. Rep. 2019, 19, 81.

- Halban, P.A.; Polonsky, K.S.; Bowden, D.W.; Hawkins, M.A.; Ling, C.; Mather, K.J.; Powers, A.C.; Rhodes, C.J.; Sussel, L.; Weir, G.C. β-Cell failure in type 2 diabetes: Postulated mechanisms and prospects for prevention and treatment. Diabetes Care 2014, 37, 1751–1758.

- Murai, N.; Saito, N.; Kodama, E.; Iida, T.; Mikura, K.; Imai, H.; Kaji, M.; Hashizume, M.; Kigawa, Y.; Koizumi, G.; et al. Insulin and Proinsulin Dynamics Progressively Deteriorate from within the Normal Range Toward Impaired Glucose Tolerance. J. Endocr. Soc. 2020, 4, bvaa066.

- Quan, W.; Jo, E.K.; Lee, M.S. Role of pancreatic β-cell death and inflammation in diabetes. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2013, 15, 141–151.

- Mohawk, J.A.; Green, C.B.; Takahashi, J.S. Central and Peripheral clocks. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2012, 35, 445–462.

- Panda, S. Circadian physiology of metabolism. Physiol. Behav. 2016, 176, 139–148.

- Perelis, M.; Marcheva, B.; Moynihan Ramsey, K.; Schipma, M.J.; Hutchison, A.L.; Taguchi, A.; Peek, C.B.; Hong, H.; Huang, W.; Omura, C.; et al. Pancreatic β-cell Enhancers Regulate Rhythmic Transcription of Genes Controlling Insulin Secretion. Science 2015, 350, aac4250.

- Saad, A.; Man, C.D.; Nandy, D.K.; Levine, J.A.; Bharucha, A.E.; Rizza, R.A.; Basu, R.; Carter, R.E.; Cobelli, C.; Kudva, Y.C.; et al. Diurnal Pattern to Insulin Secretion and Insulin Action in Healthy Individuals. Diabetes 2012, 61, 2691–2700.

- van Cauter, E.; Blackman, J.D.; Roland, D.; Spire, J.-P.; Refetoff, S.; Polonsky, K.S. Modulation of glucose regulation and insulin secretion by circadian rhythmicity and sleep. J. Clin. Investig. 1991, 88, 934–942.

- Picinato, M.C.; Haber, E.P.; Carpinelli, A.R.; Cipolla-Neto, J. Daily rhythm of glucose-induced insulin secretion by isolated islets from intact and pinealectomized rat. J. Pineal Res. 2002, 33, 172–177.

- Sheets, A.R.; Fülöp, P.; Derdák, Z.; Kassai, A.; Sabo, E.; Mark, N.M.; Paragh, G.; Wands, J.R.; Baffy, G. Uncoupling protein-2 modulates the lipid metabolic response to fasting in mice. Am. J. Physiol.-Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2008, 294, 1017–1024.

- Affourtit, C.; Brand, M.D. On the role of uncoupling protein-2 in pancreatic beta cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Bioenerg. 2008, 1777, 973–979.

- Boivin, D.B.; Boudreau, P. Impacts of shift work on sleep and circadian rhythms. Pathol. Biol. 2014, 62, 292–301.

- Karlsson, B.; Knutsson, A.; Lindahl, B. Is there an association between shift work and having a metabolic syndrome? Results from a population based study of 27 485 people. Occup. Environ. Med. 2001, 58, 747–752.

- Garaulet, M.; Gómes-Abellán, P.; Alburquerque-Béjar, J.J.; Lee, Y.-C.; Ordovás, J.M.; Scheer, F.A. Timing of food intake predicts weight loss effectiveness Prof. Int. J. Obes. 2013, 37, 604–611.

- Hatori, M.; Vollmers, C.; Zarrinpar, A.; DiTacchio, L.; Bushong, E.A.; Gill, S.; Leblanc, M.; Chaix, A.; Joens, M.; Fitzpatrick, J.A.; et al. Time-restricted feeding without reducing caloric intake prevents metabolic diseases in mice fed a high-fat diet. Cell Metab. 2012, 15, 848–860.

- Chaix, A.; Zarrinpar, A.; Miu, P.; Panda, S. Time-restricted feeding is a preventative and therapeutic intervention against diverse nutritional challenges. Cell Metab. 2014, 20, 991–1005.

- Tuomi, T.; Nagorny, C.L.F.; Singh, P.; Bennet, H.; Yu, Q.; Alenkvist, I.; Isomaa, B.; Östman, B.; Söderström, J.; Pesonen, A.-K.; et al. Increased Melatonin Signaling Is a Risk Factor for Type 2 Diabetes. Cell Metab. 2016, 23, 1067–1077.

More

Information

Subjects:

Biochemistry & Molecular Biology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

983

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

13 Dec 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No