| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Zy Harifidy Rakotoarimanana | -- | 3113 | 2022-12-07 02:40:00 | | | |

| 2 | Amina Yu | Meta information modification | 3113 | 2022-12-07 03:52:55 | | |

Video Upload Options

Located on the East coast of Africa, Madagascar is the world’s fourth-biggest island; Madagascar is host to 12,000 species of vascular plants (96% endemic). Over 90% of all its wildlife is found nowhere else on earth, and 5% of all of the earth’s biodiversity is found in Madagascar. A place where environmental degradation problems have created severe erosion and water quality problems. Despite its biological and cultural diversity, Madagascar is among the poorest countries in the world, with approximately 78% of the population living in extreme poverty with an average income of less than USD 2 per day, and more than three-quarters of the population in rural areas engaged in natural resources dependent livelihood activities.

1. Legal Framework of the Environmental Considerations in Madagascar

Environmental Action Plan

-

The first environmental program (1991–1996) was characterized by a centralized approach to the management of the environment and natural resources: zoning of protected areas based on scientific criteria without consultation with local actors and stigmatization of agriculture as the main source of resource degradation;

-

The second environmental program (1997–2002) aims to optimize the management of natural resources for human development needs. The general framework for the implementation of environmental policy in its second phase is mainly focused on the intensification of more concrete actions on the ground;

-

The third environmental program (2003–2008) focuses on conserving and enhancing the size and quality of natural resources to enable sustainable economic growth and a better quality of life. The objectives of the program are the adoption by the populations of sustainable management methods for renewable natural resources and biodiversity conservation, ensuring the sustainability of the management of environmental natural resources at the national level.

2. Poverty and Environmental Degradation

4. The Strategy of Environmental Protection for Sustainable Development

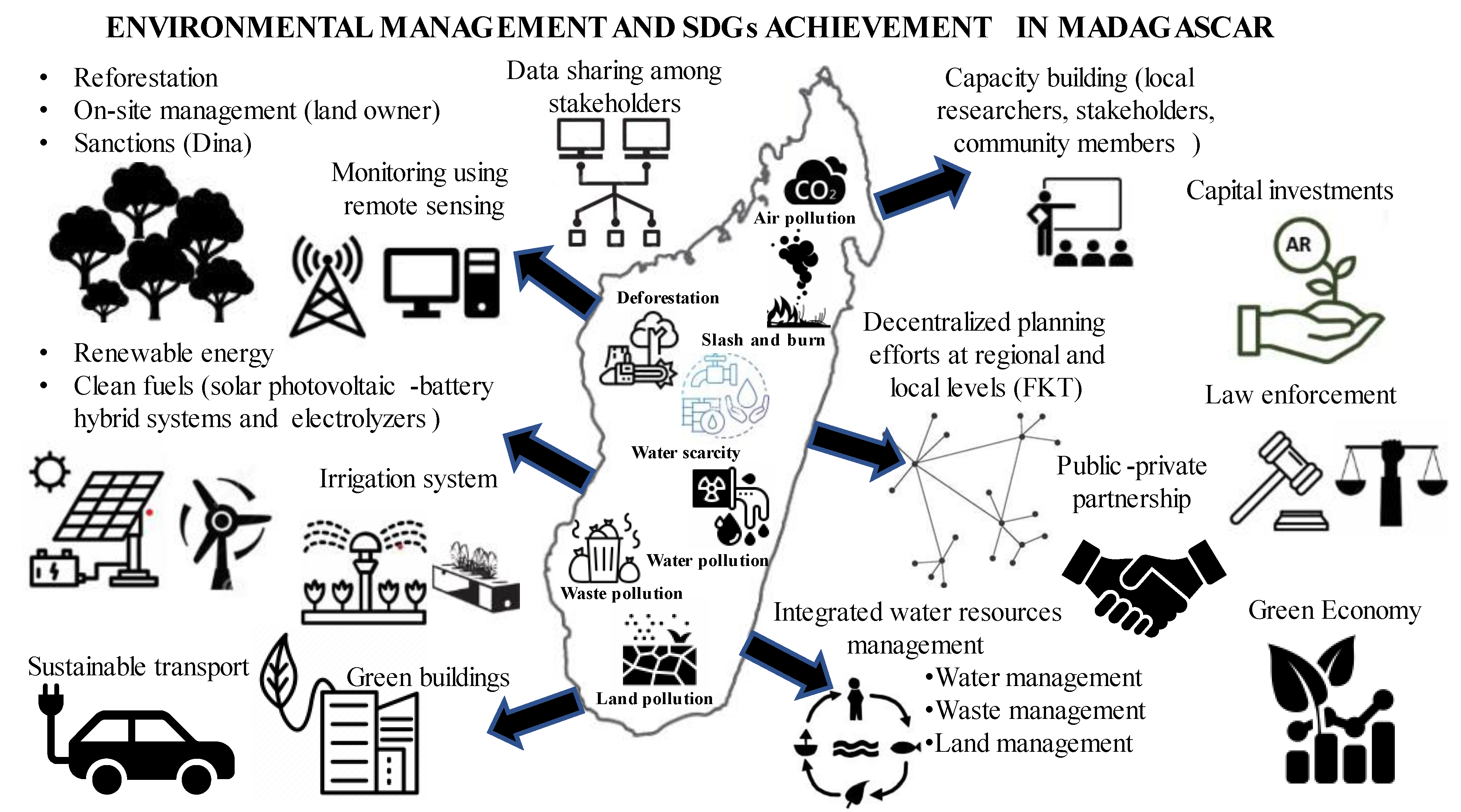

4.1. Air Pollution Reduction Strategy

4.2. Water Pollution Strategy

-

Development of integrated water resources management to promote cleaner, more resource-friendly, and sustainable methods of extraction and recycling of water and by establishing economic measures that support the rational use of water resources;

-

Development of public–private partnerships for drinking water supply or improvement of the irrigation system.

4.3. Reducing and Managing Climate Change Risks

-

Strengthening the technical capacities of stakeholders and affected entities about the climate-smart approaches to generate benefits both for mitigation and adaptation while improving livelihoods and maintaining ecosystem services;

-

Monitoring and evaluation of the costs and effectiveness of the various climate-smart landscape measures to achieve adaptation, mitigation, and improved livelihoods for the scaling-up and replication of these measures in other regions;

-

Ensuring that financial resources are sustained beyond the closure of the project to support climate efforts in high-value landscapes in Madagascar through capital investments in a trust fund dedicated to climate change;

-

Integrating strategies and actions of national policies on climate change in the decentralized planning efforts at regional and local levels.

4.4. Green Economy

4.5. Renewable Energy Sources

4.6. Raising Public Awareness of the Environmental Issues

References

- Ministere de l’Environnement, des Eaux et Forêts. Mise en Compatibilité des Investissements Avec l’Environnement (DecretMECIE), Journal Officiel n° 2648 du 10 Juillet 2000 Et n° 2904 Du 24 Mai 2004. Available online: https://edbm.mg/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Decret_MECIE.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Randimby, B.; Razafintsalama, N.; Andriamampianina, L.; Reed, E.; Raheliarisoa, S.; Andriamahenina, F.; Andrianavalomanampy, T.; Andriamalala, H. An inventory of initiatives/activities and legislation pertaining to ecosystem service payment schemes (PES) in Madagascar. Wash. DC For. Trends. Retrieved Dec. 2006, 20, 2007.

- Rakotomalala, F.T.C.; Ramambazafy, R.N.J.M.; Rakotondramanana, A.L.H.; Andrianarizaka, M.T. Importance of sustainable development culture in the practice of sustainable development in Malagasy PMEs. Int. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. Rev. (IJASER) 2022, 3, 70–87.

- World Bank. Madagascar Country Environmental Analysis: Taking Stock and Moving Forward; World Bank: Washington, WA, USA, 2013; Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/33934 (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- ONE. Loi n° 2015-003 portant Charte de l’Environnement Malagasy actualisée. Available online: https://www.pnae.mg/docs/ee/textes/loi-2015-003-charte-environnement-malagasy.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2022).

- Declaration, Stockholm. Declaration of the United Nations conference on the human environment. 1972. Available online: http://www.UNEP.org (accessed on 5 August 2022).

- Greve, A.M.; Lampietti, J.; Falloux, F. National environmental action plans in Sub-Saharan Africa. World Bank Work. Pap. Ser. 1995, 20973, 1.

- Voahangy Ramaromisa. The Situation of the Main Indicators Environmental in Madagascar; IIED: London, UK, 2007.

- Freudenberger, K.S. Paradise Lost? Lessons from 25 Years of Environmental Programs in Madagascar; USAID: Washington, WA, USA, 2010.

- Wolf, M.J.; Emerson, J.W.; Esty, D.C.; de Sherbinin, A.; Wendling, Z.A. Environmental Performance Index. New Haven, CT: Yale Center for Environmental Law & Policy. 2022. Available online: https://www.epi.yale.edu (accessed on 17 November 2022).

- Wunder, S. Poverty alleviation and tropical forests—what scope for synergies? World Dev. 2001, 29, 1817–1833.

- WCED, S.W.S. World commission on environment and development. Our Common Future 1987, 17, 1–91.

- Agabi, J.A. Biodiversity Loss in Nigerian Environment; Macmillan: Lagos, Nigeria, 1995.

- Abang, S.O. The Nigerian Environment and Social—Economic Pressure; Macmillan Nigeria for Nigerian Conservation Foundation: Lagos, Nigeria, 1995.

- Omotor, D.G. Environmental Problems and Sustainable Development in Nigeria. J. Dev. Stud. 2000, 2, 146–149.

- DFID. Poverty and the Environment: “What the Poor Say. Environment Policy”; Key sheet No. 1; DFID: London, UK, 2001.

- DFID. Making Connections. Infrastructure for Poverty Reduction; DFID: London, UK, 2002.

- Broad, R. The poor and the environment: Friends or foes? World Dev. 1994, 22, 811–822.

- Reardon, T.; Vosti, S.A. Links between rural poverty and the environment in developing countries: Asset categories and investment poverty. World Dev. 1995, 23, 1495–1506.

- Durning, A.B. Poverty and the Environment: Reversing the Downward Spiral; Worldwatch Paper 92; Worldwatch Institute: Washington, WA, USA, 1989.

- Cleaver, K.M.; Schreiber, G.A. Reversing the Spiral: The Population, Agriculture, and Environment Nexus in Sub-Saharan Africa; WorldBank: Washington, WA, USA, 1994.

- Ekbom, A.; Boĵ, J. Poverty and Environment: Evidence of Links a Integration in the Country Assistance Strategy Process; Discussion Paper No. 4; World Bank Africa Region: Washington, WA, USA, 1999.

- Mittal, I.; Gupta, R.K. Natural resources depletion and economic growth in present era. SOCH-Mastnath. J. Sci. Technol. 2015, 10, 3.

- Metz, J.J. A Reassessment of the Causes and Severity of Nepal’s Environmental Crisis. World Dev. 1991, 19, 805–820.

- Jodha, N.S. Poverty-Environmental Resource Degradation Links: Questioning the Basic Premises; International Center for Integrated Mountain Development: Lalitpur, Nepal, 1998.

- Somanathan, E. Deforestation, property rights and incentives in central Himalayas. Econ. Polit. Weekly 1991, 26, 37–46.

- Jenkins, R.K.B.; Keane, A.; Rakotoarivelo, A.R.; Rakotomboavonjy, V.; Randrianandrianina, F.H.; Razafimanahaka, H.J.; Ralaiarimalala, S.R.; Jones, J.P.G. Analysis of patterns of bushmeat consumption reveals extensive exploitation of protected species in eastern Madagascar. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e27570.

- Golden, C.D.; Fernald, L.C.H.; Brashares, J.S.; Rasolofoniaina, B.J.R.; Kremen, C. Benefits of wildlife consumption to child nutrition in a biodiversity hotspot. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 19653–19656.

- Randriamalala, H.; Liu, Z. Rosewood of Madagascar: Between democracy and conservation. Madag. Conserv. Dev. 2010, 5.

- Wilmé, L.; Innes, J.L.; Schuurman, D.; Ramamonjisoa, B.; Langrand, M. The elephant in the room: Madagascar’s rosewood stocks and stockpiles. Conserv. Letters. 2020, 13, e12714.

- Harifidy, R.Z.; Hiroshi, I. Analysis of River Basin Management in Madagascar and Lessons Learned from Japan. Water 2022, 14, 449.

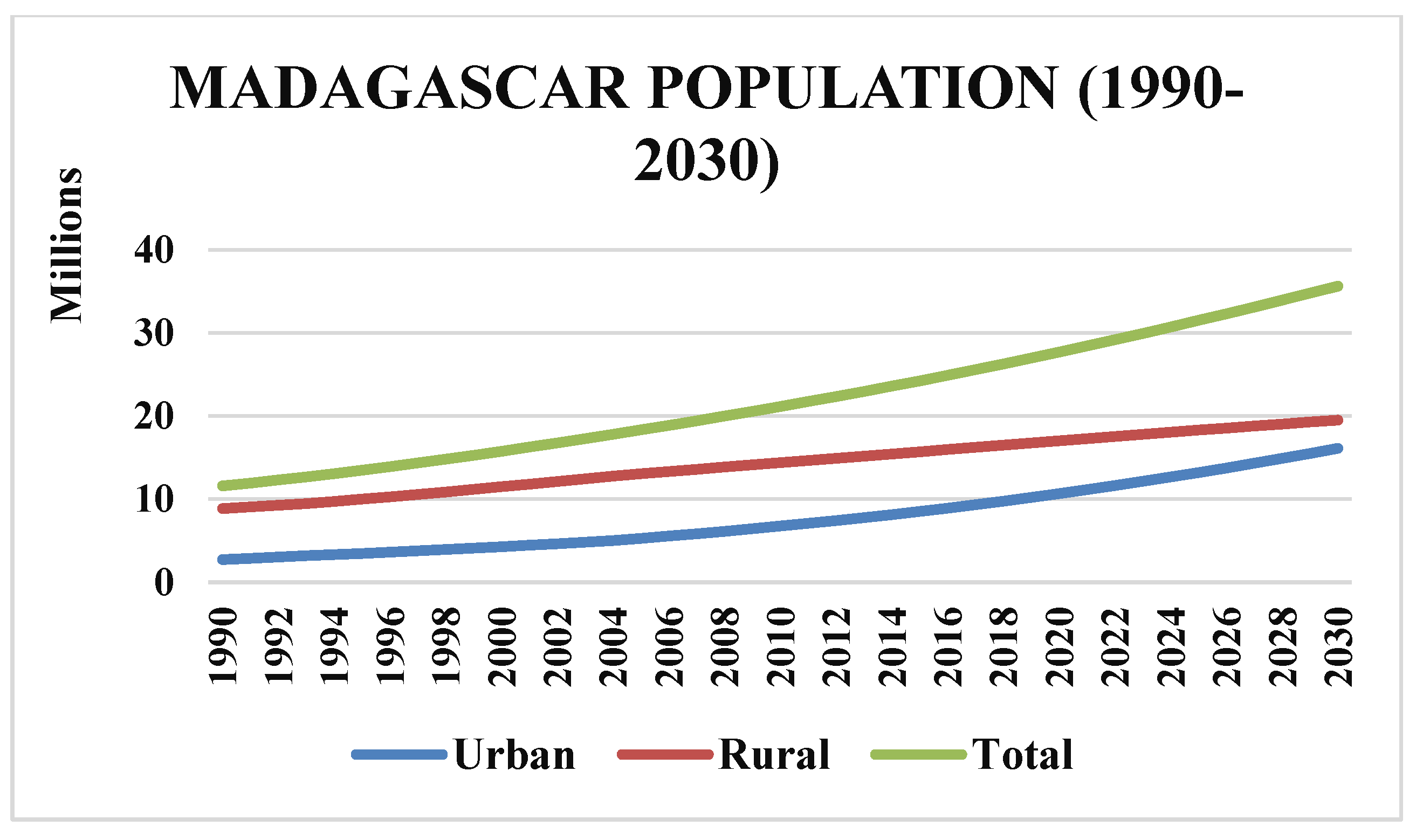

- UNDESA. How Accurate Are the United Nations World Population Projections? Popul. Dev. Rev. 2019, 24, 15.

- Wada, Y.; Flörke, M.; Hanasaki, N.; Eisner, S.; Fischer, G.; Tramberend, S.; Satoh, Y.; Van Vliet, M.T.H.; Yillia, P.; Ringler, C.J.G.M.D.; et al. Modeling global water use for the 21st century: The Water Futures and Solutions (WFaS) initiative and its approaches. Geosci. Model Dev. 2016, 9, 175–222.

- United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and World Health Organization (WHO). Progress on Drinking Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene in Schools: 2000–2021 Data Update; United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and World Health Organization (WHO): New York, NY, USA, 2022.

- Chowdhary, P.; Bharagava, R.N.; Mishra, S.; Khan, N. Role of Industries in Water Scarcity and Its Adverse Effects on Environment and Human Health. In Environmental Concerns and Sustainable Development; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 235–256.

- Hanjra, M.A.; Qureshi, M.E. Global water crisis and future food security in an era of climate change. Food Policy 2010, 3, 365–377.

- Sachs, J.; Kroll, C.; Lafortune, G.; Fuller, G.; Woelm, F. Sustainable Development Report 2022; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022.

- Transparency International. Corruption Perceptions Index. 2017. Available online: www.transparency.org/news/feature/corruption_perceptions_index_2017#table (accessed on 16 September 2022).

- Vieilledent, G.; Nourtier, M.; Grinand, C.; Pedrono, M.; Clausen, A.; Rabetrano, T.; Rakotoarijaona, J.R.; Rakotoarivelo, B.; Rakotomalala, F.A.; Rakotomalala, L.; et al. It’s not just poverty: Unregulated global market and bad governance explain unceasing deforestation in Western Madagascar. BioRxiv 2020.

- Razafindratsima, O.H.; Kamoto, J.F.; Sills, E.O.; Mutta, D.N.; Song, C.; Kabwe, G.; Castle, S.E.; Kristjanson, P.M.; Ryan, C.M.; Brockhaus, M.; et al. Reviewing the evidence on the roles of forests and tree-based systems in poverty dynamics. For. Policy Econ. 2021, 131, 102576.

- Scales, I.R. The Drivers of Deforestation and the Complexity of Land Use in Madagascar. In Conservation and Environmental Management in Madagascar; Scales, I.R., Ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2014; pp. 05–126.

- Pedroso, J.R.; Murrieta, R.S.S.; Adams, C. A agricultura de corte e queima: Um sistema em transformação. Boletim do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi, Ciências Humanas. Belém 2008, 3, 153–174.

- Brinkmann, K.; Noromiarilanto, F.; Ratovonamana, R.Y.; Buekert, A. Deforestation processes in South-Western Madagascar over the past 40 years: What can we learn from settlement characteristics? Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2014, 195, 231–243.

- Delač, D.; Kisić, I.; Zgorelec, Ž.; Perčin, A.; Pereira, P. Slash-pile burning impacts on the quality of runoff waters in a Mediterranean environment (Croatia). Catena 2022, 218, 106559.

- Wang, G.; Zhu, T.; Zhou, J.; Yu, Y.; Petropoulos, E.; Müller, C. Slash-and-burn in karst regions lowers soil gross nitrogen (N) transformation rates and N-turnover. Geoderma 2022, 425, 116084.

- Frappier-Brinton, T.; Lehman, S.M. The burning island: Spatiotemporal patterns of fire occurrence in Madagascar. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263313.

- Eklund, J.; Jones, J.P.; Räsänen, M.; Geldmann, J.; Jokinen, A.P.; Pellegrini, A.; Rakotobe, D.; Rakotonarivo, O.S.; Toivonen, T.; Balmford, A. Elevated fires during COVID-19 lockdown and the vulnerability of protected areas. Nat. Sustain. 2022, 5, 603–609.

- Jones, J.P.; Rakotonarivo, O.S.; Razafimanahaka, J.H. Forest conservation in Madagascar: Past, Present, and Future. In The New Natural History of Madagascar; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2021.

- Schüßler, D.; Richter, T.; Mantilla-Contreras, J. Educational approaches to encourage pro-environmental behaviors in Madagascar. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3148.

- Madagascar; World Bank; USAID; Cooperation Suisse; UNESCO; UNDP; World Wildlife Fund. Madagascar—Environmental Action Plan, (French); World Bank Group: Washington, WA, USA, 2010; Volume 2, Available online: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/344971468756961739/Madagascar-Environmental-action-plan (accessed on 26 September 2022).

- Ministry of the Environment. The green and blue economy in Madagascar. 2021. Available online: https://www.environnement.mg/thematique-rubrique/economie-verte/ (accessed on 17 August 2022).

- Reibelt, L.M.; Richter, T.; Rendigs, A.; Mantilla-Contreras, J. Malagasy conservationists and environmental educators: Life paths into conservation. Sustainability 2017, 9, 227.