| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Vivi Li | -- | 7990 | 2022-12-02 01:44:35 |

Video Upload Options

Compartmental models are a very general modelling technique. They are often applied to the mathematical modelling of infectious diseases. The population is assigned to compartments with labels – for example, S, I, or R, (Susceptible, Infectious, or Recovered). People may progress between compartments. The order of the labels usually shows the flow patterns between the compartments; for example SEIS means susceptible, exposed, infectious, then susceptible again. The origin of such models is the early 20th century, with important works being that of Ross in 1916, Ross and Hudson in 1917, Kermack and McKendrick in 1927 and Kendall in 1956 The models are most often run with ordinary differential equations (which are deterministic), but can also be used with a stochastic (random) framework, which is more realistic but much more complicated to analyze. Models try to predict things such as how a disease spreads, or the total number infected, or the duration of an epidemic, and to estimate various epidemiological parameters such as the reproductive number. Such models can show how different public health interventions may affect the outcome of the epidemic, e.g., what the most efficient technique is for issuing a limited number of vaccines in a given population.

1. The SIR Model

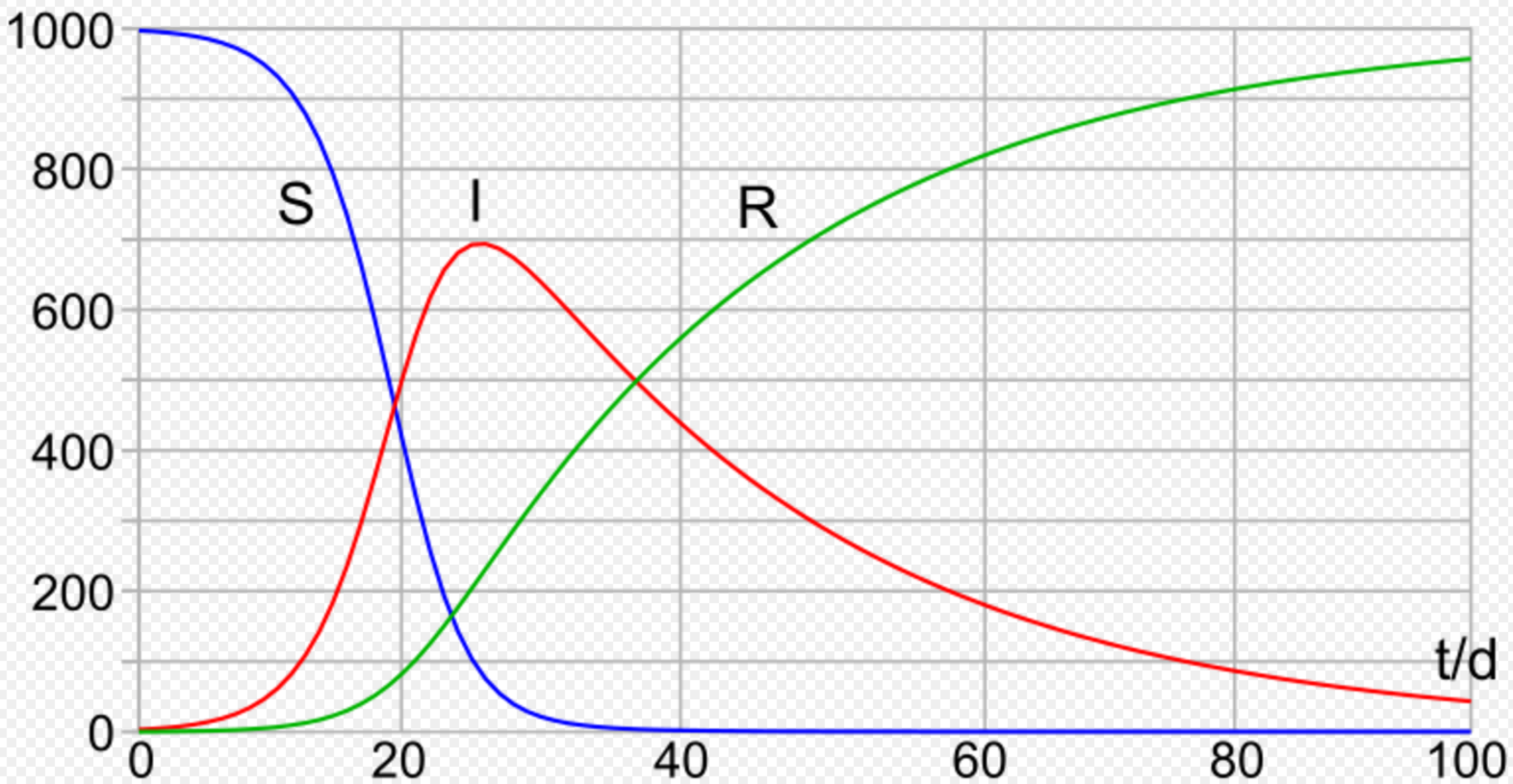

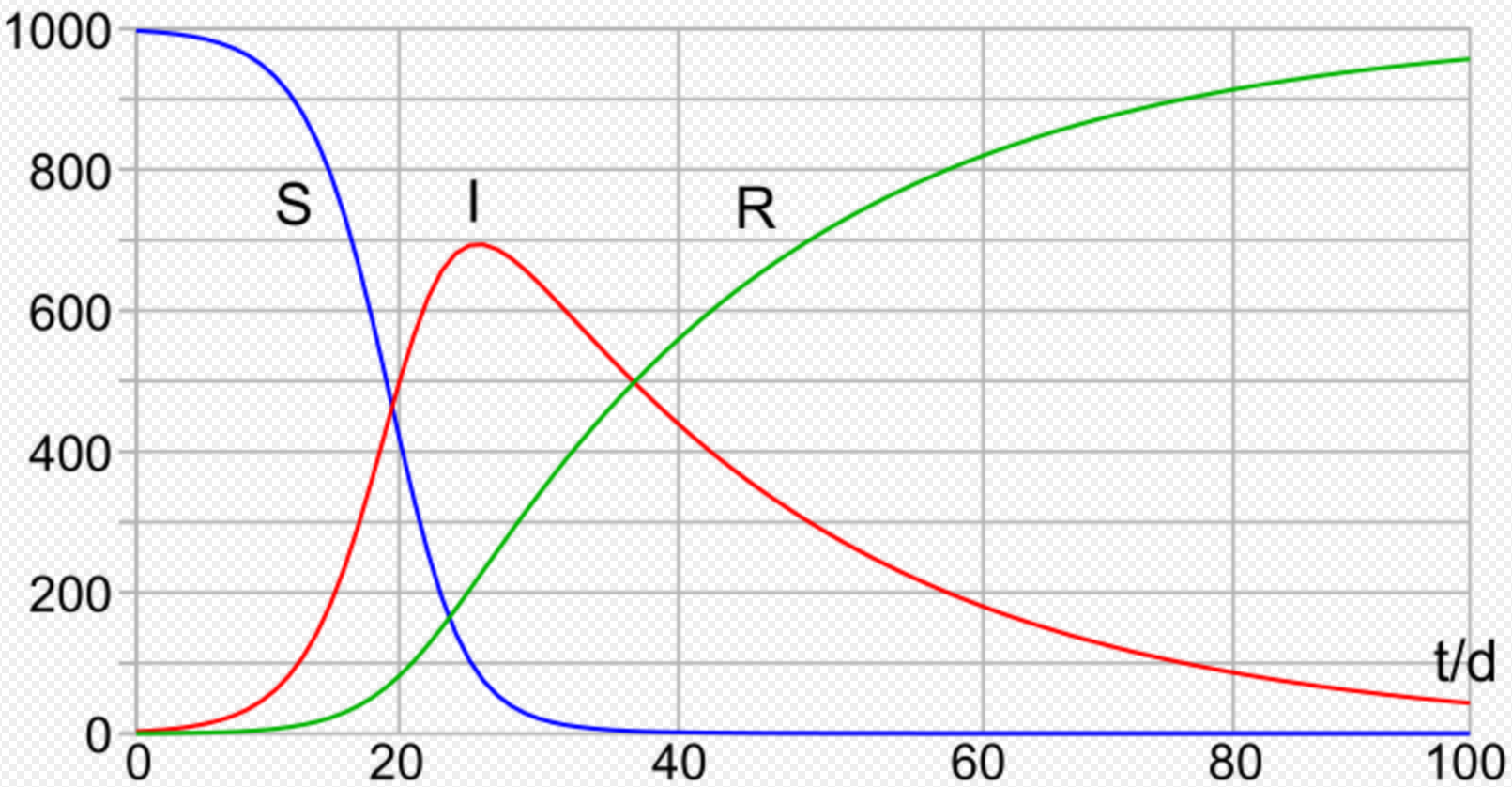

The SIR model[1][2][3][4] is one of the simplest compartmental models, and many models are derivatives of this basic form. The model consists of three compartments:-

- S: The number of susceptible individuals. When a susceptible and an infectious individual come into "infectious contact", the susceptible individual contracts the disease and transitions to the infectious compartment.

- I: The number of infectious individuals. These are individuals who have been infected and are capable of infecting susceptible individuals.

- R for the number of removed (and immune) or deceased individuals. These are individuals who have been infected and have either recovered from the disease and entered the removed compartment, or died. It is assumed that the number of deaths is negligible with respect to the total population. This compartment may also be called "recovered" or "resistant".

This model is reasonably predictive[5] for infectious diseases that are transmitted from human to human, and where recovery confers lasting resistance, such as measles, mumps and rubella.

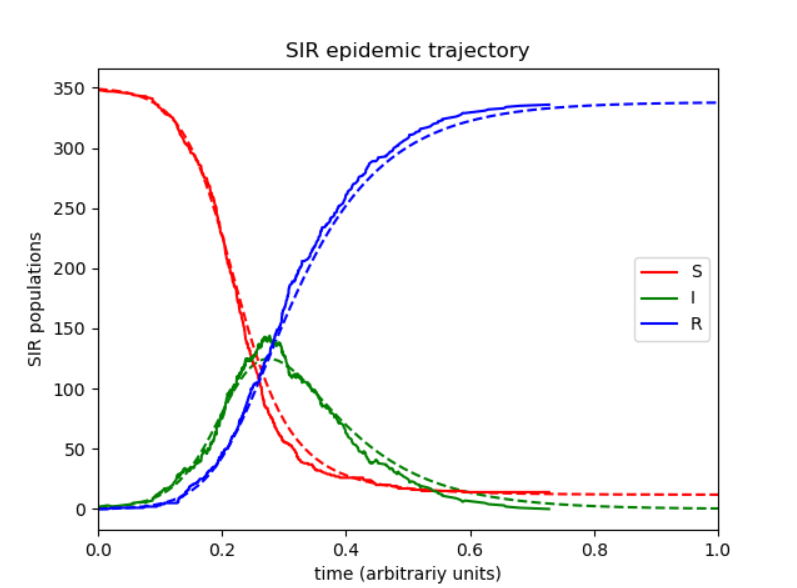

These variables (S, I, and R) represent the number of people in each compartment at a particular time. To represent that the number of susceptible, infectious and removed individuals may vary over time (even if the total population size remains constant), we make the precise numbers a function of t (time): S(t), I(t) and R(t). For a specific disease in a specific population, these functions may be worked out in order to predict possible outbreaks and bring them under control.[5]

As implied by the variable function of t, the model is dynamic in that the numbers in each compartment may fluctuate over time. The importance of this dynamic aspect is most obvious in an endemic disease with a short infectious period, such as measles in the UK prior to the introduction of a vaccine in 1968. Such diseases tend to occur in cycles of outbreaks due to the variation in number of susceptibles (S(t)) over time. During an epidemic, the number of susceptible individuals falls rapidly as more of them are infected and thus enter the infectious and removed compartments. The disease cannot break out again until the number of susceptibles has built back up, e.g. as a result of offspring being born into the susceptible compartment.

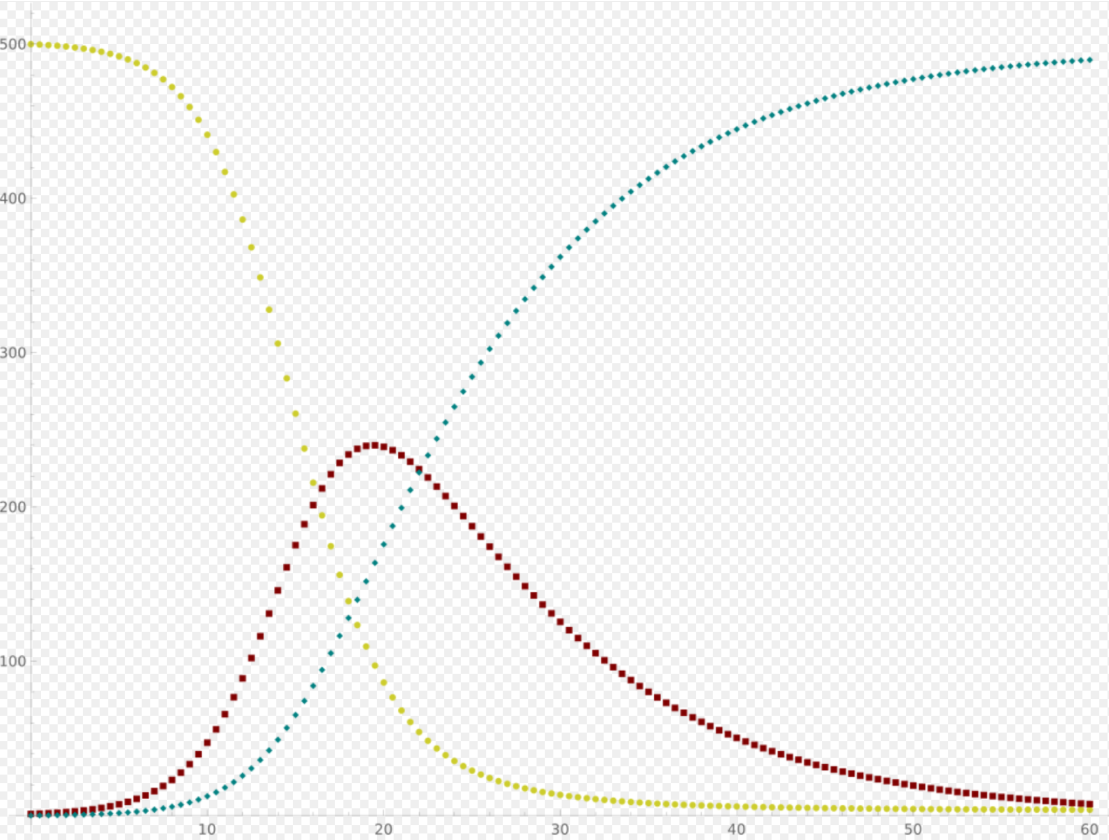

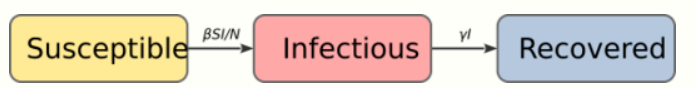

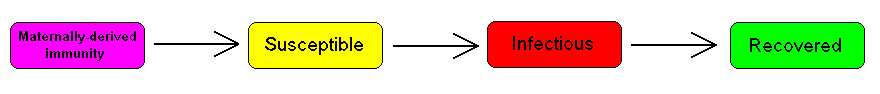

Each member of the population typically progresses from susceptible to infectious to recovered. This can be shown as a flow diagram in which the boxes represent the different compartments and the arrows the transition between compartments, i.e.

1.1. Transition Rates

For the full specification of the model, the arrows should be labeled with the transition rates between compartments. Between S and I, the transition rate is assumed to be d(S/N)/dt = -βSI/N2, where N is the total population, β is the average number of contacts per person per time, multiplied by the probability of disease transmission in a contact between a susceptible and an infectious subject, and SI/N2 is the fraction of those contacts between an infectious and susceptible individual which result in the susceptible person becoming infected. (This is mathematically similar to the law of mass action in chemistry in which random collisions between molecules result in a chemical reaction and the fractional rate is proportional to the concentration of the two reactants).

Between I and R, the transition rate is assumed to be proportional to the number of infectious individuals which is γI. This is equivalent to assuming that the probability of an infectious individual recovering in any time interval dt is simply γdt. If an individual is infectious for an average time period D, then γ = 1/D. This is also equivalent to the assumption that the length of time spent by an individual in the infectious state is a random variable with an exponential distribution. The "classical" SIR model may be modified by using more complex and realistic distributions for the I-R transition rate (e.g. the Erlang distribution[6]).

For the special case in which there is no removal from the infectious compartment (γ=0), the SIR model reduces to a very simple SI model, which has a logistic solution, in which every individual eventually becomes infected.

1.2. The SIR Model without Vital Dynamics

The dynamics of an epidemic, for example, the flu, are often much faster than the dynamics of birth and death, therefore, birth and death are often omitted in simple compartmental models. The SIR system without so-called vital dynamics (birth and death, sometimes called demography) described above can be expressed by the following system of ordinary differential equations:[2][7]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \left\{\begin{aligned} & \frac{dS}{dt} = - \frac{\beta I S}{N}, \\[6pt] & \frac{dI}{dt} = \frac{\beta I S}{N}- \gamma I, \\[6pt] & \frac{dR}{dt} = \gamma I, \end{aligned}\right. }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ S }[/math] is the stock of susceptible population, [math]\displaystyle{ I }[/math] is the stock of infected, [math]\displaystyle{ R }[/math] is the stock of removed population (either by death or recovery), and [math]\displaystyle{ N }[/math] is the sum of these three.

This model was for the first time proposed by William Ogilvy Kermack and Anderson Gray McKendrick as a special case of what we now call Kermack–McKendrick theory, and followed work McKendrick had done with Ronald Ross.

This system is non-linear, however it is possible to derive its analytic solution in implicit form.[1] Firstly note that from:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{dS}{dt} + \frac{dI}{dt} + \frac{dR}{dt} = 0, }[/math]

it follows that:

- [math]\displaystyle{ S(t) + I(t) + R(t) = \text{constant} = N, }[/math]

expressing in mathematical terms the constancy of population [math]\displaystyle{ N }[/math]. Note that the above relationship implies that one need only study the equation for two of the three variables.

Secondly, we note that the dynamics of the infectious class depends on the following ratio:

- [math]\displaystyle{ R_0 = \frac{\beta}{\gamma}, }[/math]

the so-called basic reproduction number (also called basic reproduction ratio). This ratio is derived as the expected number of new infections (these new infections are sometimes called secondary infections) from a single infection in a population where all subjects are susceptible.[8][9] This idea can probably be more readily seen if we say that the typical time between contacts is [math]\displaystyle{ T_{c} = \beta^{-1} }[/math], and the typical time until removal is [math]\displaystyle{ T_{r} = \gamma^{-1} }[/math]. From here it follows that, on average, the number of contacts by an infectious individual with others before the infectious has been removed is: [math]\displaystyle{ T_{r}/T_{c}. }[/math]

By dividing the first differential equation by the third, separating the variables and integrating we get

- [math]\displaystyle{ S(t) = S(0) e^{-R_0(R(t) - R(0))/N}, }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ S(0) }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ R(0) }[/math] are the initial numbers of, respectively, susceptible and removed subjects. Writing [math]\displaystyle{ s_0 = S(0) / N }[/math] for the initial proportion of susceptible individuals, and [math]\displaystyle{ s_\infty = S(\infty) / N }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ r_\infty = R(\infty) / N }[/math] for the proportion of susceptible and removed individuals respectively in the limit [math]\displaystyle{ t \to \infty, }[/math] one has

- [math]\displaystyle{ s_\infty = 1 - r_\infty = s_0 e^{-R_0(r_\infty - r_0)} }[/math]

(note that the infectious compartment empties in this limit). This transcendental equation has a solution in terms of the Lambert W function,[10] namely

- [math]\displaystyle{ s_\infty = 1-r_\infty = - R_0^{-1}\, W(-s_0 R_0 e^{-R_0(1-r_0)}). }[/math]

This shows that at the end of an epidemic that conforms to the simple assumptions of the SIR model, unless [math]\displaystyle{ s_0=0 }[/math], not all individuals of the population have been removed, so some must remain susceptible. A driving force leading to the end of an epidemic is a decline in the number of infectious individuals. The epidemic does not typically end because of a complete lack of susceptible individuals.

The role of both the basic reproduction number and the initial susceptibility are extremely important. In fact, upon rewriting the equation for infectious individuals as follows:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{dI}{dt} = \left(R_0 \frac{S}{N} - 1\right) \gamma I, }[/math]

it yields that if:

- [math]\displaystyle{ R_{0} \cdot S(0) \gt N, }[/math]

then:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{dI}{dt}(0) \gt 0 , }[/math]

i.e., there will be a proper epidemic outbreak with an increase of the number of the infectious (which can reach a considerable fraction of the population). On the contrary, if

- [math]\displaystyle{ R_{0} \cdot S(0) \lt N, }[/math]

then

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{dI}{dt}(0) \lt 0 , }[/math]

i.e., independently from the initial size of the susceptible population the disease can never cause a proper epidemic outbreak. As a consequence, it is clear that both the basic reproduction number and the initial susceptibility are extremely important.

The force of infection

Note that in the above model the function:

- [math]\displaystyle{ F = \beta I, }[/math]

models the transition rate from the compartment of susceptible individuals to the compartment of infectious individuals, so that it is called the force of infection. However, for large classes of communicable diseases it is more realistic to consider a force of infection that does not depend on the absolute number of infectious subjects, but on their fraction (with respect to the total constant population [math]\displaystyle{ N }[/math]):

- [math]\displaystyle{ F = \beta \frac{I}{N} . }[/math]

Capasso[11] and, afterwards, other authors have proposed nonlinear forces of infection to model more realistically the contagion process.

Exact analytical solutions to the SIR model

In 2014, Harko and coauthors derived an exact so-called analytical solution (involving an integral that can only be calculated numerically) to the SIR model.[1] In the case without vital dynamics setup, for [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{S}(u)=S(t) }[/math], etc., it corresponds to the following time parametrization

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{S}(u)= S(0)u }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{I}(u)= N -\mathcal{R}(u)-\mathcal{S}(u) }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{R}(u)=R(0) -\rho \ln(u) }[/math]

for

- [math]\displaystyle{ t= \frac{N}{\beta}\int_u^1 \frac{du^*}{u^*\mathcal{I}(u^*)} , \quad \rho=\frac{\gamma N}{\beta}, }[/math]

with initial conditions

- [math]\displaystyle{ (\mathcal{S}(1),\mathcal{I}(1),\mathcal{R}(1))=(S(0),N -R(0)-S(0),R(0)), \quad u_T\lt u\lt 1, }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ u_T }[/math] satisfies [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{I}(u_T)=0 }[/math]. By the transcendental equation for [math]\displaystyle{ R_{\infty} }[/math] above, it follows that [math]\displaystyle{ u_T=e^{-(R_{\infty}-R(0))/\rho}(=S_{\infty}/S(0) }[/math], if [math]\displaystyle{ S(0) \neq 0) }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ I_{\infty}=0 }[/math].

An equivalent so-called analytical solution (involving an integral that can only be calculated numerically) found by Miller[12][13] yields

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} S(t) & = S(0) e^{-\xi(t)} \\[8pt] I(t) & = N-S(t)-R(t) \\[8pt] R(t) & = R(0) + \rho \xi(t) \\[8pt] \xi(t) & = \frac{\beta}{N}\int_0^t I(t^*) \, dt^* \end{align} }[/math]

Here [math]\displaystyle{ \xi(t) }[/math] can be interpreted as the expected number of transmissions an individual has received by time [math]\displaystyle{ t }[/math]. The two solutions are related by [math]\displaystyle{ e^{-\xi(t)} = u }[/math].

Effectively the same result can be found in the original work by Kermack and McKendrick.[14]

These solutions may be easily understood by noting that all of the terms on the right-hand sides of the original differential equations are proportional to [math]\displaystyle{ I }[/math]. The equations may thus be divided through by [math]\displaystyle{ I }[/math], and the time rescaled so that the differential operator on the left-hand side becomes simply [math]\displaystyle{ d/d\tau }[/math], where [math]\displaystyle{ d\tau=I dt }[/math], i.e. [math]\displaystyle{ \tau=\int I dt }[/math]. The differential equations are now all linear, and the third equation, of the form [math]\displaystyle{ dR/d\tau = }[/math] const., shows that [math]\displaystyle{ \tau }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ R }[/math] (and [math]\displaystyle{ \xi }[/math] above) are simply linearly related.

A highly accurate analytic approximant of the SIR model as well as exact analytic expressions for the final values [math]\displaystyle{ S_{\infty} }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ I_{\infty} }[/math], and [math]\displaystyle{ R_{\infty} }[/math] were provided by Kröger and Schlickeiser,[3] so that there is no need to perform a numerical integration to solve the SIR model, to obtain its parameters from existing data, or to predict the future dynamics of an epidemics modeled by the SIR model. The approximant involves the Lambert W function which is part of all basic data visualization software such as Microsoft Excel, MATLAB, and Mathematica.

While Kendall[15] considered the so-called all-time SIR model where the initial conditions [math]\displaystyle{ S(0) }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ I(0) }[/math], and [math]\displaystyle{ R(0) }[/math] are coupled through the above relations, Kermack and McKendrick[14] proposed to study the more general semi-time case, for which [math]\displaystyle{ S(0) }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ I(0) }[/math] are both arbitrary. This latter version, denoted as semi-time SIR model,[3] makes predictions only for future times [math]\displaystyle{ t\gt 0 }[/math]. An analytic approximant and exact expressions for the final values are available for the semi-time SIR model as well.[4]

1.3. The SIR Model with Vital Dynamics and Constant Population

Consider a population characterized by a death rate [math]\displaystyle{ \mu }[/math] and birth rate [math]\displaystyle{ \Lambda }[/math], and where a communicable disease is spreading.[2] The model with mass-action transmission is:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \frac{dS}{dt} & = \Lambda - \mu S - \frac{\beta I S}{N} \\[8pt] \frac{dI}{dt} & = \frac{\beta I S}{N} - \gamma I -\mu I \\[8pt] \frac{dR}{dt} & = \gamma I - \mu R \end{align} }[/math]

for which the disease-free equilibrium (DFE) is:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \left(S(t),I(t),R(t)\right) =\left(\frac{\Lambda}{\mu},0,0\right). }[/math]

In this case, we can derive a basic reproduction number:

- [math]\displaystyle{ R_0 = \frac{ \beta}{\mu+\gamma}, }[/math]

which has threshold properties. In fact, independently from biologically meaningful initial values, one can show that:

- [math]\displaystyle{ R_0 \le 1 \Rightarrow \lim_{t \to \infty} (S(t),I(t),R(t)) = \textrm{DFE} = \left(\frac{\Lambda}{\mu},0,0\right) }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ R_0 \gt 1 , I(0)\gt 0 \Rightarrow \lim_{t \to \infty} (S(t),I(t),R(t)) = \textrm{EE} = \left(\frac{\gamma+\mu}{\beta},\frac{\mu}{\beta}\left(R_0-1\right), \frac{\gamma}{\beta} \left(R_0-1\right)\right). }[/math]

The point EE is called the Endemic Equilibrium (the disease is not totally eradicated and remains in the population). With heuristic arguments, one may show that [math]\displaystyle{ R_{0} }[/math] may be read as the average number of infections caused by a single infectious subject in a wholly susceptible population, the above relationship biologically means that if this number is less than or equal to one the disease goes extinct, whereas if this number is greater than one the disease will remain permanently endemic in the population.

1.4. The SIR Model

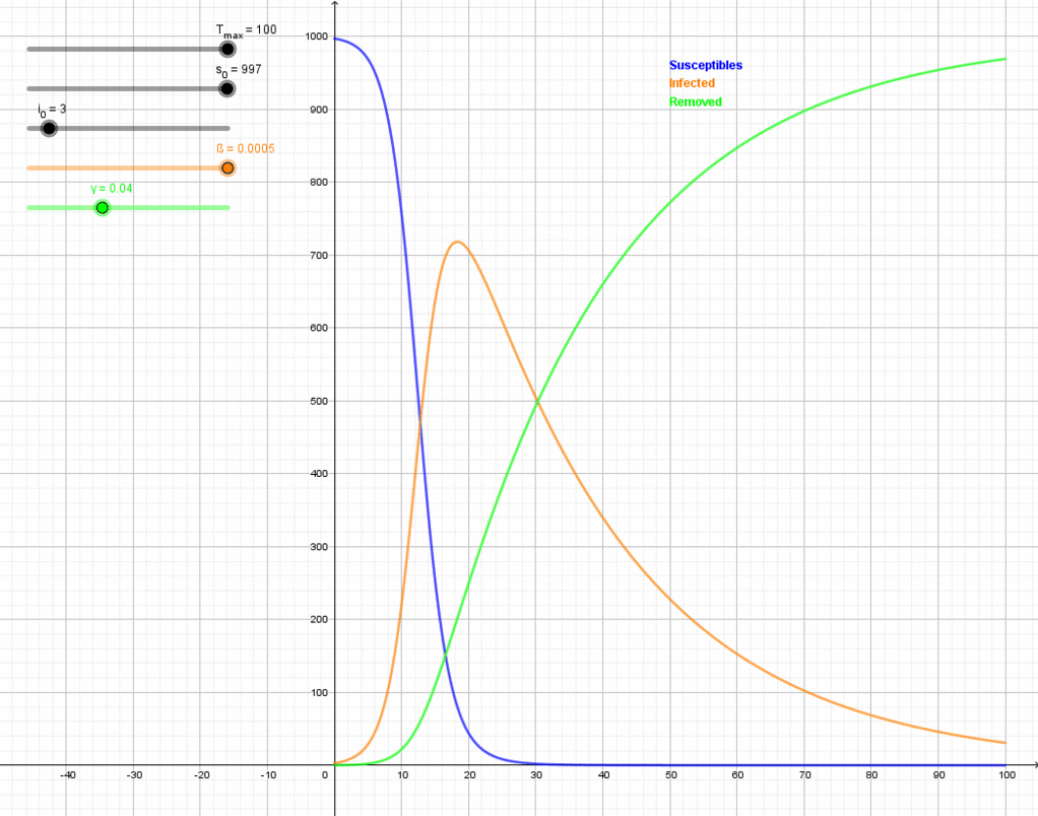

In 1927, W. O. Kermack and A. G. McKendrick created a model in which they considered a fixed population with only three compartments: susceptible, [math]\displaystyle{ S(t) }[/math]; infected, [math]\displaystyle{ I(t) }[/math]; and recovered, [math]\displaystyle{ R(t) }[/math]. The compartments used for this model consist of three classes:[14]

- [math]\displaystyle{ S(t) }[/math] is used to represent the individuals not yet infected with the disease at time t, or those susceptible to the disease of the population.

- [math]\displaystyle{ I(t) }[/math] denotes the individuals of the population who have been infected with the disease and are capable of spreading the disease to those in the susceptible category.

- [math]\displaystyle{ R(t) }[/math] is the compartment used for the individuals of the population who have been infected and then removed from the disease, either due to immunization or due to death. Those in this category are not able to be infected again or to transmit the infection to others.

The flow of this model may be considered as follows:

- [math]\displaystyle{ {\color{blue}{\mathcal{S} \rightarrow \mathcal{I} \rightarrow \mathcal{R}}} }[/math]

Using a fixed population, [math]\displaystyle{ N = S(t) + I(t) + R(t) }[/math] in the three functions resolves that the value [math]\displaystyle{ N }[/math] should remain constant within the simulation, if a simulation is used to solve the SIR model. Alternatively, the analytic approximant[3] can be used without performing a simulation. The model is started with values of [math]\displaystyle{ S(t=0) }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ I(t=0) }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ R(t=0) }[/math]. These are the number of people in the susceptible, infected and removed categories at time equals zero. If the SIR model is assumed to hold at all times, these initial conditions are not independent.[3] Subsequently, the flow model updates the three variables for every time point with set values for [math]\displaystyle{ \beta }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma }[/math]. The simulation first updates the infected from the susceptible and then the removed category is updated from the infected category for the next time point (t=1). This describes the flow persons between the three categories. During an epidemic the susceptible category is not shifted with this model, [math]\displaystyle{ \beta }[/math] changes over the course of the epidemic and so does [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma }[/math]. These variables determine the length of the epidemic and would have to be updated with each cycle.

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{dS}{dt} = - \frac{\beta S I}{N} }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{dI}{dt} = \frac{\beta S I}{N} - \gamma I }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{dR}{dt} = \gamma I }[/math]

Several assumptions were made in the formulation of these equations: First, an individual in the population must be considered as having an equal probability as every other individual of contracting the disease with a rate of [math]\displaystyle{ a }[/math] and an equal fraction [math]\displaystyle{ b }[/math] of people that an individual makes contact with per unit time. Then, let [math]\displaystyle{ \beta }[/math] be the multiplication of [math]\displaystyle{ a }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ b }[/math]. This is the transmission probability times the contact rate. Besides, an infected individual makes contact with [math]\displaystyle{ b }[/math] persons per unit time whereas only a fraction, [math]\displaystyle{ S/N }[/math] of them are susceptible.Thus, we have every infective can infect [math]\displaystyle{ a b S = \beta S }[/math] susceptible persons, and therefore, the whole number of susceptibles infected by infectives per unit time is [math]\displaystyle{ \beta S I }[/math]. For the second and third equations, consider the population leaving the susceptible class as equal to the number entering the infected class. However, a number equal to the fraction [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma }[/math] (which represents the mean recovery/death rate, or [math]\displaystyle{ 1/\gamma }[/math] the mean infective period) of infectives are leaving this class per unit time to enter the removed class. These processes which occur simultaneously are referred to as the Law of Mass Action, a widely accepted idea that the rate of contact between two groups in a population is proportional to the size of each of the groups concerned. Finally, it is assumed that the rate of infection and recovery is much faster than the time scale of births and deaths and therefore, these factors are ignored in this model.[16]

1.5. Steady-State Solutions

The expected duration of susceptibility will be [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname E[\min(T_L\mid T_S)] }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ T_L }[/math] reflects the time alive (life expectancy) and [math]\displaystyle{ T_S }[/math] reflects the time in the susceptible state before becoming infected, which can be simplified[17] to:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname E[\min(T_L\mid T_S)]=\int_0^\infty e^{-(\mu+\delta) x} \, dx= \frac{1}{\mu+\delta}, }[/math]

such that the number of susceptible persons is the number entering the susceptible compartment [math]\displaystyle{ \mu N }[/math] times the duration of susceptibility:

- [math]\displaystyle{ S = \frac{\mu N}{\mu + \lambda}. }[/math]

Analogously, the steady-state number of infected persons is the number entering the infected state from the susceptible state (number susceptible, times rate of infection [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda = \tfrac{\beta I}{N}, }[/math] times the duration of infectiousness [math]\displaystyle{ \tfrac{1}{\mu+v} }[/math]:

- [math]\displaystyle{ I = \frac{\mu N}{\mu + \lambda} \lambda \frac{1}{\mu + v}. }[/math]

1.6. Other Compartmental Models

There are many modifications of the SIR model, including those that include births and deaths, where upon recovery there is no immunity (SIS model), where immunity lasts only for a short period of time (SIRS), where there is a latent period of the disease where the person is not infectious (SEIS and SEIR), and where infants can be born with immunity (MSIR).

2. Variations on the Basic SIR Model

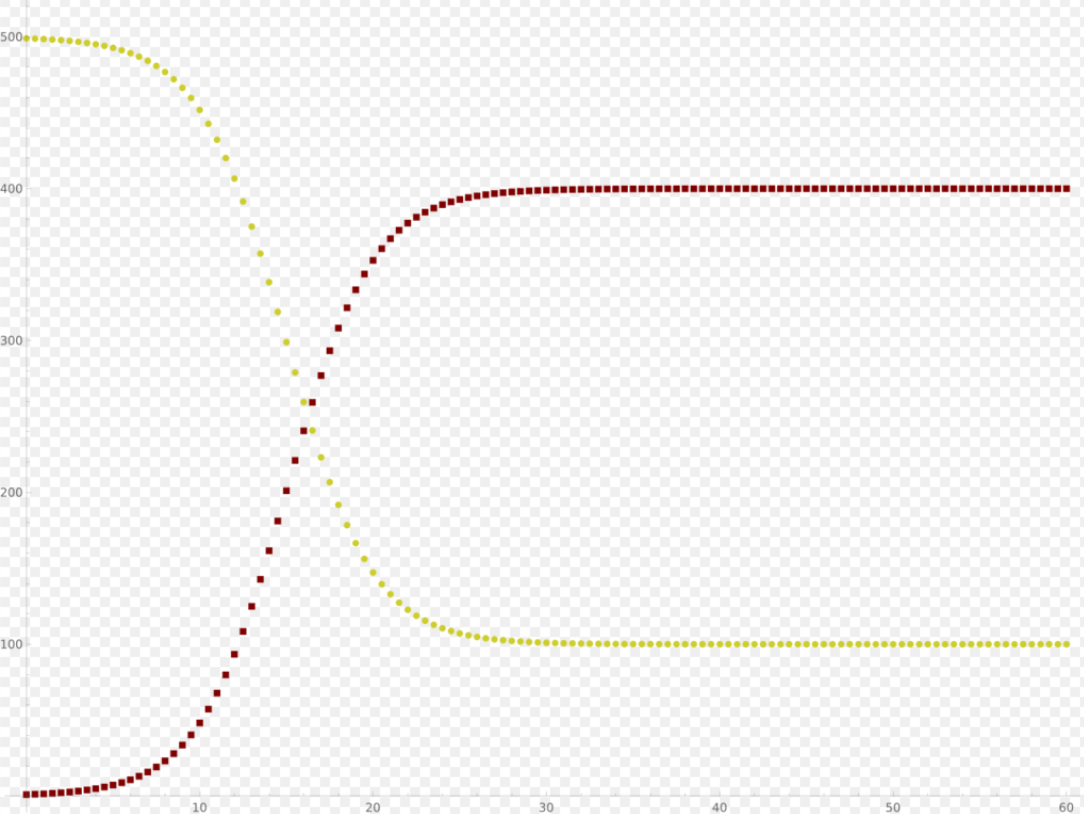

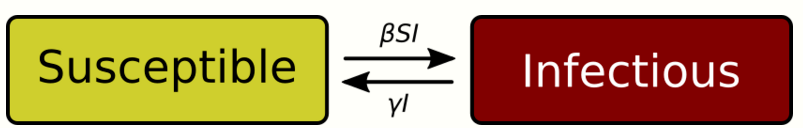

2.1. The SIS Model

Some infections, for example, those from the common cold and influenza, do not confer any long-lasting immunity. Such infections do not give immunity upon recovery from infection, and individuals become susceptible again.

SIS compartmental model. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=2040720

We have the model:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \frac{dS}{dt} & = - \frac{\beta S I}{N} + \gamma I \\[6pt] \frac{dI}{dt} & = \frac{\beta S I}{N} - \gamma I \end{align} }[/math]

Note that denoting with N the total population it holds that:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{dS}{dt} + \frac{dI}{dt} = 0 \Rightarrow S(t)+I(t) = N }[/math].

It follows that:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{dI}{dt} = (\beta - \gamma) I - \frac{\beta}{N} I^2 }[/math],

i.e. the dynamics of infectious is ruled by a logistic function, so that [math]\displaystyle{ \forall I(0) \gt 0 }[/math]:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & \frac{\beta}{\gamma} \le 1 \Rightarrow \lim_{t \to +\infty}I(t)=0, \\[6pt] & \frac{\beta}{\gamma} \gt 1 \Rightarrow \lim_{t \to +\infty}I(t) = \left(1 - \frac{\gamma}{\beta} \right) N. \end{align} }[/math]

It is possible to find an analytical solution to this model (by making a transformation of variables: [math]\displaystyle{ I = y^{-1} }[/math] and substituting this into the mean-field equations),[18] such that the basic reproduction rate is greater than unity. The solution is given as

- [math]\displaystyle{ I(t) = \frac{I_\infty}{1+V e^{-\chi t}} }[/math].

where [math]\displaystyle{ I_\infty = (1 -\gamma/\beta)N }[/math] is the endemic infectious population, [math]\displaystyle{ \chi = \beta-\gamma }[/math], and [math]\displaystyle{ V = I_\infty/I_0 - 1 }[/math]. As the system is assumed to be closed, the susceptible population is then [math]\displaystyle{ S(t) = N - I(t) }[/math].

As a special case, one obtains the usual logistic function by assuming [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma=0 }[/math]. This can be also considered in the SIR model with [math]\displaystyle{ R=0 }[/math], i.e. no removal will take place. That is the SI model.[19] The differential equation system using [math]\displaystyle{ S=N-I }[/math] thus reduces to:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{dI}{dt} \propto I\cdot (N-I). }[/math]

In the long run, in the SI model, all individuals will become infected. For evaluating the epidemic threshold in the SIS model on networks see Parshani et al.[20]

2.2. The SIRD Model

The Susceptible-Infectious-Recovered-Deceased model differentiates between Recovered (meaning specifically individuals having survived the disease and now immune) and Deceased.[8] This model uses the following system of differential equations:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & \frac{dS}{dt} = - \frac{\beta I S}{N}, \\[6pt] & \frac{dI}{dt} = \frac{\beta I S}{N} - \gamma I - \mu I, \\[6pt] & \frac{dR}{dt} = \gamma I, \\[6pt] & \frac{dD}{dt} = \mu I, \end{align} }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ \beta, \gamma, \mu }[/math] are the rates of infection, recovery, and mortality, respectively.[21]

2.3. The SIRV Model

The Susceptible-Infectious-Recovered-Vaccinated model is an extended SIR model that accounts for vaccination of the susceptible population.[22] This model uses the following system of differential equations:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & \frac{dS}{dt} = - \frac{\beta(t) I S}{N} - v(t) S, \\[6pt] & \frac{dI}{dt} = \frac{\beta(t) I S}{N} - \gamma(t) I, \\[6pt] & \frac{dR}{dt} = \gamma(t) I, \\[6pt] & \frac{dV}{dt} = v(t) S, \end{align} }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ \beta, \gamma, v }[/math] are the rates of infection, recovery, and vaccination, respectively. For the semi-time initial conditions [math]\displaystyle{ S(0)=(1-\eta)N }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ I(0)=\eta N }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ R(0)=V(0)=0 }[/math] and constant ratios [math]\displaystyle{ k=\gamma(t)/\beta(t) }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ b=v(t)/\beta(t) }[/math] the model had been solved approximately.[22] The occurrence of a pandemic outburst requires [math]\displaystyle{ k+b\lt 1-2\eta }[/math] and there is a critical reduced vaccination rate [math]\displaystyle{ b_c }[/math] beyond which the steady-state size [math]\displaystyle{ S_\infty }[/math]of the susceptible compartment remains relatively close to [math]\displaystyle{ S(0) }[/math]. Arbitrary initial conditions satisfying [math]\displaystyle{ S(0)+I(0)+R(0)+V(0)=N }[/math] can be mapped to the solved special case with [math]\displaystyle{ R(0)=V(0)=0 }[/math].[22]

2.4. The MSIR Model

For many infections, including measles, babies are not born into the susceptible compartment but are immune to the disease for the first few months of life due to protection from maternal antibodies (passed across the placenta and additionally through colostrum). This is called passive immunity. This added detail can be shown by including an M class (for maternally derived immunity) at the beginning of the model.

To indicate this mathematically, an additional compartment is added, M(t). This results in the following differential equations: https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1452231

-

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \frac{dM}{dt} & = \Lambda - \delta M - \mu M\\[8pt] \frac{dS}{dt} & = \delta M - \frac{\beta SI}{N} - \mu S\\[8pt] \frac{dI}{dt} & = \frac{\beta SI}{N} - \gamma I - \mu I\\[8pt] \frac{dR}{dt} & = \gamma I - \mu R \end{align} }[/math]

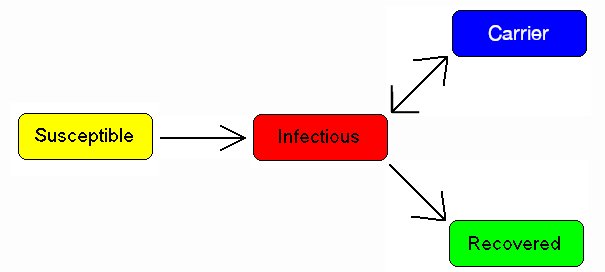

2.5. Carrier State

Some people who have had an infectious disease such as tuberculosis never completely recover and continue to carry the infection, whilst not suffering the disease themselves. They may then move back into the infectious compartment and suffer symptoms (as in tuberculosis) or they may continue to infect others in their carrier state, while not suffering symptoms. The most famous example of this is probably Mary Mallon, who infected 22 people with typhoid fever. The carrier compartment is labelled C.

A simple modification of previous image by Viki Male to make the word "Carrier" plainly visible. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1266629

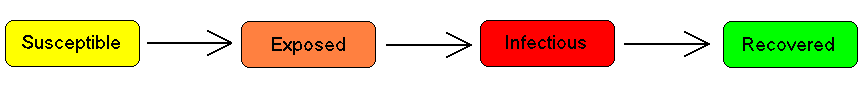

2.6. The SEIR Model

For many important infections, there is a significant latency period during which individuals have been infected but are not yet infectious themselves. During this period the individual is in compartment E (for exposed).

SEIR compartmental model. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1671667

Assuming that the latency period is a random variable with exponential distribution with parameter [math]\displaystyle{ a }[/math] (i.e. the average latency period is [math]\displaystyle{ a^{-1} }[/math]), and also assuming the presence of vital dynamics with birth rate [math]\displaystyle{ \Lambda }[/math] equal to death rate [math]\displaystyle{ N\mu }[/math] (so that the total number [math]\displaystyle{ N }[/math] is constant), we have the model:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \frac{dS}{dt} & = \mu N - \mu S - \frac{\beta I S}{N} \\[8pt] \frac{dE}{dt} & = \frac{\beta I S}{N} - (\mu +a ) E \\[8pt] \frac{dI}{dt} & = a E - (\gamma +\mu ) I \\[8pt] \frac{dR}{dt} & = \gamma I - \mu R. \end{align} }[/math]

We have [math]\displaystyle{ S+E+I+R=N, }[/math] but this is only constant because of the simplifying assumption that birth and death rates are equal; in general [math]\displaystyle{ N }[/math] is a variable.

For this model, the basic reproduction number is:

- [math]\displaystyle{ R_0 = \frac{a}{\mu+a}\frac{\beta}{\mu+\gamma}. }[/math]

Similarly to the SIR model, also, in this case, we have a Disease-Free-Equilibrium (N,0,0,0) and an Endemic Equilibrium EE, and one can show that, independently from biologically meaningful initial conditions

- [math]\displaystyle{ \left(S(0),E(0),I(0),R(0)\right) \in \left\{(S,E,I,R)\in [0,N]^4 : S \ge 0, E \ge 0, I\ge 0, R\ge 0, S+E+I+R = N \right\} }[/math]

it holds that:

- [math]\displaystyle{ R_0 \le 1 \Rightarrow \lim_{t \to +\infty} \left(S(t),E(t),I(t),R(t)\right) = DFE = (N,0,0,0), }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ R_0 \gt 1 , I(0)\gt 0 \Rightarrow \lim_{t \to +\infty} \left(S(t),E(t),I(t),R(t)\right) = EE. }[/math]

In case of periodically varying contact rate [math]\displaystyle{ \beta(t) }[/math] the condition for the global attractiveness of DFE is that the following linear system with periodic coefficients:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \frac{dE_1}{dt} & = \beta(t) I_1 - (\gamma +a ) E_1 \\[8pt] \frac{dI_1}{dt} & = a E_1 - (\gamma +\mu ) I_1 \end{align} }[/math]

is stable (i.e. it has its Floquet's eigenvalues inside the unit circle in the complex plane).

2.7. The SEIS Model

The SEIS model is like the SEIR model (above) except that no immunity is acquired at the end.

-

-

- [math]\displaystyle{ {\color{blue}{\mathcal{S} \to \mathcal{E} \to \mathcal{I} \to \mathcal{S}}} }[/math]

-

In this model an infection does not leave any immunity thus individuals that have recovered return to being susceptible, moving back into the S(t) compartment. The following differential equations describe this model:

-

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \frac{dS}{dt} & = \Lambda - \frac{\beta SI}{N} - \mu S + \gamma I \\[6pt] \frac{dE}{dt} & = \frac{\beta SI}{N} - (\epsilon + \mu)E \\[6pt] \frac{dI}{dt} & = \varepsilon E - (\gamma + \mu)I \end{align} }[/math]

2.8. The MSEIR Model

For the case of a disease, with the factors of passive immunity, and a latency period there is the MSEIR model.

-

-

- [math]\displaystyle{ \color{blue}{\mathcal{M} \to \mathcal{S} \to \mathcal{E} \to \mathcal{I} \to \mathcal{R}} }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \frac{dM}{dt} & = \Lambda - \delta M - \mu M \\[6pt] \frac{dS}{dt} & = \delta M - \frac{\beta SI}{N} - \mu S \\[6pt] \frac{dE}{dt} & = \frac{\beta SI}{N} - (\varepsilon + \mu)E \\[6pt] \frac{dI}{dt} & = \varepsilon E - (\gamma + \mu)I \\[6pt] \frac{dR}{dt} & = \gamma I - \mu R \end{align} }[/math]

-

2.9. The MSEIRS Model

An MSEIRS model is similar to the MSEIR, but the immunity in the R class would be temporary, so that individuals would regain their susceptibility when the temporary immunity ended.

-

-

- [math]\displaystyle{ {\color{blue}{\mathcal{M} \to \mathcal{S} \to \mathcal{E} \to \mathcal{I} \to \mathcal{R} \to \mathcal{S}}} }[/math]

-

2.10. Variable Contact rates

It is well known that the probability of getting a disease is not constant in time. As a pandemic progresses, reactions to the pandemic may change the contact rates which are assumed constant in the simpler models. Counter-measures such as masks, social distancing and lockdown will alter the contact rate in a way to reduce the speed of the pandemic.

In addition, Some diseases are seasonal, such as the common cold viruses, which are more prevalent during winter. With childhood diseases, such as measles, mumps, and rubella, there is a strong correlation with the school calendar, so that during the school holidays the probability of getting such a disease dramatically decreases. As a consequence, for many classes of diseases, one should consider a force of infection with periodically ('seasonal') varying contact rate

- [math]\displaystyle{ F = \beta(t) \frac{I}{N} , \quad \beta(t+T)=\beta(t) }[/math]

with period T equal to one year.

Thus, our model becomes

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \frac{dS}{dt} & = \mu N - \mu S - \beta(t) \frac{I}{N} S \\[8pt] \frac{dI}{dt} & = \beta(t) \frac{I}{N} S - (\gamma +\mu ) I \end{align} }[/math]

(the dynamics of recovered easily follows from [math]\displaystyle{ R=N-S-I }[/math]), i.e. a nonlinear set of differential equations with periodically varying parameters. It is well known that this class of dynamical systems may undergo very interesting and complex phenomena of nonlinear parametric resonance. It is easy to see that if:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac 1 T \int_0^T \frac{\beta(t)}{\mu+\gamma} \, dt \lt 1 \Rightarrow \lim_{t \to +\infty} (S(t),I(t)) = DFE = (N,0), }[/math]

whereas if the integral is greater than one the disease will not die out and there may be such resonances. For example, considering the periodically varying contact rate as the 'input' of the system one has that the output is a periodic function whose period is a multiple of the period of the input. This allowed to give a contribution to explain the poly-annual (typically biennial) epidemic outbreaks of some infectious diseases as interplay between the period of the contact rate oscillations and the pseudo-period of the damped oscillations near the endemic equilibrium. Remarkably, in some cases, the behavior may also be quasi-periodic or even chaotic.

2.11. SIR Model with Diffusion

Spatiotemporal compartmental models describe not the total number, but the density of susceptible/infective/recovered persons. Consequently, they also allow to model the distribution of infected persons in space. In most cases, this is done by combining the SIR model with a diffusion equation

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & \partial_t S = D_S \nabla^2 S - \frac{\beta I S}{N}, \\[6pt] & \partial_t I = D_I \nabla^2 I + \frac{\beta I S}{N}- \gamma I, \\[6pt] & \partial_t R = D_R \nabla^2 R + \gamma I, \end{align} }[/math][23]

where [math]\displaystyle{ D_S }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ D_I }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ D_R }[/math] are diffusion constants. Thereby, one obtains a reaction-diffusion equation. (Note that, for dimensional reasons, the parameter [math]\displaystyle{ \beta }[/math] has to be changed compared to the simple SIR model.) Early models of this type have been used to model the spread of the black death in Europe.[24] Extensions of this model have been used to incorporate, e.g., effects of nonpharmaceutical interventions such as social distancing.[25]

2.12. Interacting Subpopulation SEIR Model

As social contacts, disease severity and lethality, as well as the efficacy of prophylactic measures may differ substantially between interacting subpopulations, e.g., the elderly versus the young, separate SEIR models for each subgroup may be used that are mutually connected through interaction links.[26] Such Interacting Subpopulation SEIR models have been used for modeling the Covid-19 pandemic at continent scale to develop personalized, accelerated, subpopulation-targeted vaccination strategies[27] that promise a shortening of the pandemic and a reduction of case and death counts in the setting of limited access to vaccines during a wave of virus Variants of Concern.

2.13. Pandemic

A SIR community based model to assess the probability for a worldwide spreading of a pandemic has been developed by Valdez et al.[28]

2.14. SIR Model on Networks

The SIR model has been studied on networks of various kinds in order to model a more realistic form of connection than the homogeneous mixing condition which is usually required. A simple model for epidemics on networks in which an individual has a probability p of being infected by each of his infected neighbors in a given time step leads to results similar to giant component formation on Erdos Renyi random graphs.[29]

3. Modelling Vaccination

The SIR model can be modified to model vaccination.[30] Typically these introduce an additional compartment to the SIR model, [math]\displaystyle{ V }[/math], for vaccinated individuals. Below are some examples.

3.1. Vaccinating Newborns

In presence of a communicable diseases, one of the main tasks is that of eradicating it via prevention measures and, if possible, via the establishment of a mass vaccination program. Consider a disease for which the newborn are vaccinated (with a vaccine giving lifelong immunity) at a rate [math]\displaystyle{ P \in (0,1) }[/math]:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \frac{dS}{dt} & = \nu N (1-P) - \mu S - \beta \frac{I}{N} S \\[8pt] \frac{dI}{dt} & = \beta \frac{I}{N} S - (\mu+\gamma) I \\[8pt] \frac{dV}{dt} & = \nu N P - \mu V \end{align} }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ V }[/math] is the class of vaccinated subjects. It is immediate to show that:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \lim_{t \to +\infty} V(t)= N P, }[/math]

thus we shall deal with the long term behavior of [math]\displaystyle{ S }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ I }[/math], for which it holds that:

- [math]\displaystyle{ R_0 (1-P) \le 1 \Rightarrow \lim_{t \to +\infty} \left(S(t),I(t)\right) = DFE = \left(N \left(1-P\right),0\right) }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ R_0 (1-P) \gt 1 , \quad I(0)\gt 0 \Rightarrow \lim_{t \to +\infty} \left(S(t),I(t)\right) = EE = \left(\frac{N}{R_0(1-P)},N \left(R_0 (1-P)-1\right)\right). }[/math]

In other words, if

- [math]\displaystyle{ P \lt P^{*}= 1-\frac{1}{R_0} }[/math]

the vaccination program is not successful in eradicating the disease, on the contrary, it will remain endemic, although at lower levels than the case of absence of vaccinations. This means that the mathematical model suggests that for a disease whose basic reproduction number may be as high as 18 one should vaccinate at least 94.4% of newborns in order to eradicate the disease.

3.2. Vaccination and Information

Modern societies are facing the challenge of "rational" exemption, i.e. the family's decision to not vaccinate children as a consequence of a "rational" comparison between the perceived risk from infection and that from getting damages from the vaccine. In order to assess whether this behavior is really rational, i.e. if it can equally lead to the eradication of the disease, one may simply assume that the vaccination rate is an increasing function of the number of infectious subjects:

- [math]\displaystyle{ P=P(I), \quad P'(I)\gt 0. }[/math]

In such a case the eradication condition becomes:

- [math]\displaystyle{ P(0) \ge P^{*}, }[/math]

i.e. the baseline vaccination rate should be greater than the "mandatory vaccination" threshold, which, in case of exemption, cannot hold. Thus, "rational" exemption might be myopic since it is based only on the current low incidence due to high vaccine coverage, instead taking into account future resurgence of infection due to coverage decline.

3.3. Vaccination of Non-Newborns

In case there also are vaccinations of non newborns at a rate ρ the equation for the susceptible and vaccinated subject has to be modified as follows:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \frac{dS}{dt} & = \mu N (1-P) - \mu S - \rho S - \beta \frac{I}{N} S \\[8pt] \frac{dV}{dt} & = \mu N P + \rho S - \mu V \end{align} }[/math]

leading to the following eradication condition:

- [math]\displaystyle{ P \ge 1- \left(1+\frac{\rho}{\mu}\right)\frac{1}{R_0} }[/math]

3.4. Pulse Vaccination Strategy

This strategy repeatedly vaccinates a defined age-cohort (such as young children or the elderly) in a susceptible population over time. Using this strategy, the block of susceptible individuals is then immediately removed, making it possible to eliminate an infectious disease, (such as measles), from the entire population. Every T time units a constant fraction p of susceptible subjects is vaccinated in a relatively short (with respect to the dynamics of the disease) time. This leads to the following impulsive differential equations for the susceptible and vaccinated subjects:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \frac{dS}{dt} & = \mu N - \mu S - \beta \frac{I}{N} S, \quad S(n T^+) = (1-p) S(n T^-), & & n=0,1,2,\ldots \\[8pt] \frac{dV}{dt} & = - \mu V, \quad V(n T^+) = V(n T^-) + p S(n T^-), & & n=0,1,2,\ldots \end{align} }[/math]

It is easy to see that by setting I = 0 one obtains that the dynamics of the susceptible subjects is given by:

- [math]\displaystyle{ S^*(t) = 1- \frac{p}{1-(1-p)E^{-\mu T}} E^{-\mu MOD(t,T)} }[/math]

and that the eradication condition is:

- [math]\displaystyle{ R_0 \int_0^T S^*(t) \, dt \lt 1 }[/math]

4. The Influence of Age: Age-structured Models

Age has a deep influence on the disease spread rate in a population, especially the contact rate. This rate summarizes the effectiveness of contacts between susceptible and infectious subjects. Taking into account the ages of the epidemic classes [math]\displaystyle{ s(t,a),i(t,a),r(t,a) }[/math] (to limit ourselves to the susceptible-infectious-removed scheme) such that:

- [math]\displaystyle{ S(t)=\int_0^{a_M} s(t,a)\,da }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ I(t)=\int_0^{a_M} i(t,a)\,da }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ R(t)=\int_0^{a_M} r(t,a)\,da }[/math]

(where [math]\displaystyle{ a_M \le +\infty }[/math] is the maximum admissible age) and their dynamics is not described, as one might think, by "simple" partial differential equations, but by integro-differential equations:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \partial_t s(t,a) + \partial_a s(t,a) = -\mu(a) s(a,t) - s(a,t)\int_0^{a_M} k(a,a_1;t)i(a_1,t)\,da_1 }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \partial_t i(t,a) + \partial_a i(t,a) = s(a,t)\int_{0}^{a_M}{k(a,a_1;t)i(a_1,t)da_1} -\mu(a) i(a,t) - \gamma(a)i(a,t) }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \partial_t r(t,a) + \partial_a r(t,a) = -\mu(a) r(a,t) + \gamma(a)i(a,t) }[/math]

where:

- [math]\displaystyle{ F(a,t,i(\cdot,\cdot))=\int_0^{a_M} k(a,a_1;t)i(a_1,t) \, da_1 }[/math]

is the force of infection, which, of course, will depend, though the contact kernel [math]\displaystyle{ k(a,a_1;t) }[/math] on the interactions between the ages.

Complexity is added by the initial conditions for newborns (i.e. for a=0), that are straightforward for infectious and removed:

- [math]\displaystyle{ i(t,0)=r(t,0)=0 }[/math]

but that are nonlocal for the density of susceptible newborns:

- [math]\displaystyle{ s(t,0)= \int_0^{a_M} \left(\varphi_s(a) s(a,t)+\varphi_i(a) i(a,t)+\varphi_r(a) r(a,t)\right) \, da }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ \varphi_j(a), j=s,i,r }[/math] are the fertilities of the adults.

Moreover, defining now the density of the total population [math]\displaystyle{ n(t,a)=s(t,a)+i(t,a)+r(t,a) }[/math] one obtains:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \partial_t n(t,a) + \partial_a n(t,a) = -\mu(a) n(a,t) }[/math]

In the simplest case of equal fertilities in the three epidemic classes, we have that in order to have demographic equilibrium the following necessary and sufficient condition linking the fertility [math]\displaystyle{ \varphi(.) }[/math] with the mortality [math]\displaystyle{ \mu(a) }[/math] must hold:

- [math]\displaystyle{ 1 = \int_0^{a_M} \varphi(a) \exp\left(- \int_0^a{\mu(q)dq} \right) \, da }[/math]

and the demographic equilibrium is

- [math]\displaystyle{ n^*(a)=C \exp\left(- \int_0^a \mu(q) \, dq \right), }[/math]

automatically ensuring the existence of the disease-free solution:

- [math]\displaystyle{ DFS(a)= (n^*(a),0,0). }[/math]

A basic reproduction number can be calculated as the spectral radius of an appropriate functional operator.

5. Other Considerations Within Compartmental Epidemic Models

5.1. Vertical Transmission

In the case of some diseases such as AIDS and Hepatitis B, it is possible for the offspring of infected parents to be born infected. This transmission of the disease down from the mother is called Vertical Transmission. The influx of additional members into the infected category can be considered within the model by including a fraction of the newborn members in the infected compartment.[31]

5.2. Vector Transmission

Diseases transmitted from human to human indirectly, i.e. malaria spread by way of mosquitoes, are transmitted through a vector. In these cases, the infection transfers from human to insect and an epidemic model must include both species, generally requiring many more compartments than a model for direct transmission.[31][32]

5.3. Others

Other occurrences which may need to be considered when modeling an epidemic include things such as the following:[31]

- Non-homogeneous mixing

- Variable infectivity

- Distributions that are spatially non-uniform

- Diseases caused by macroparasites

6. Deterministic Versus Stochastic Epidemic Models

It is important to stress that the deterministic models presented here are valid only in case of sufficiently large populations, and as such should be used cautiously.[33]

To be more precise, these models are only valid in the thermodynamic limit, where the population is effectively infinite. In stochastic models, the long-time endemic equilibrium derived above, does not hold, as there is a finite probability that the number of infected individuals drops below one in a system. In a true system then, the pathogen may not propagate, as no host will be infected. But, in deterministic mean-field models, the number of infected can take on real, namely, non-integer values of infected hosts, and the number of hosts in the model can be less than one, but more than zero, thereby allowing the pathogen in the model to propagate. The reliability of compartmental models is limited to compartmental applications.

One of the possible extensions of mean-field models considers the spreading of epidemics on a network based on percolation theory concepts.[29] Stochastic epidemic models have been studied on different networks[34][35][36] and more recently applied to the COVID-19 pandemic.[37]

7. Efficient Distribution of Vaccinations

A method for efficient vaccination approach, via vaccinating a small fraction population called acquaintance immunization has been developed by Cohen et al.[38] An alternative method based on identifying and vaccination mainly spreaders has been developed by Liu et al[39]

References

- Harko, Tiberiu; Lobo, Francisco S. N.; Mak, M. K. (2014). "Exact analytical solutions of the Susceptible-Infected-Recovered (SIR) epidemic model and of the SIR model with equal death and birth rates" (in en). Applied Mathematics and Computation 236: 184–194. doi:10.1016/j.amc.2014.03.030. Bibcode: 2014arXiv1403.2160H. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.amc.2014.03.030

- Beckley, Ross; Weatherspoon, Cametria; Alexander, Michael; Chandler, Marissa; Johnson, Anthony; Batt, Ghan S. (2013). "Modeling epidemics with differential equations". Tennessee State University Internal Report. http://www.tnstate.edu/mathematics/mathreu/filesreu/GroupProjectSIR.pdf. Retrieved July 19, 2020.

- Kröger, Martin; Schlickeiser, Reinhard (2020). "Analytical solution of the SIR-model for the temporal evolution of epidemics. Part A: Time-independent reproduction factor" (in en). Journal of Physics A 53 (50): 505601. doi:10.1088/1751-8121/abc65d. Bibcode: 2020JPhA...53X5601K. https://dx.doi.org/10.1088%2F1751-8121%2Fabc65d

- Schlickeiser, Reinhard; Kröger, Martin (2021). "Analytical solution of the SIR-model for the temporal evolution of epidemics. Part B: Semi-time case" (in en). Journal of Physics A 54 (17): 175601. doi:10.1088/1751-8121/abed66. Bibcode: 2021JPhA...54X5601S. https://dx.doi.org/10.1088%2F1751-8121%2Fabed66

- Yang, Wuyue; Zhang, Dongyan; Peng, Liangrong; Zhuge, Changjing; Liu, Liu (2020). "Rational evaluation of various epidemic models based on the COVID-19 data of China". arXiv:2003.05666v1 [q-bio.PE]. //arxiv.org/archive/q-bio.PE

- Krylova, O.; Earn, DJ (May 15, 2013). "Effects of the infectious period distribution on predicted transitions in childhood disease dynamics". J R Soc Interface 10 (84). doi:10.1098/rsif.2013.0098. PMID 23676892. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3673147

- Hethcote H (2000). "The Mathematics of Infectious Diseases". SIAM Review 42 (4): 599–653. doi:10.1137/s0036144500371907. Bibcode: 2000SIAMR..42..599H. https://dx.doi.org/10.1137%2Fs0036144500371907

- Bailey, Norman T. J. (1975). The mathematical theory of infectious diseases and its applications (2nd ed.). London: Griffin. ISBN 0-85264-231-8.

- Sonia Altizer; Nunn, Charles (2006). Infectious diseases in primates: behavior, ecology and evolution. Oxford Series in Ecology and Evolution. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-856585-2.

- "Mathematica, Version 12.1". Champaign IL, 2020. https://www.wolfram.com/mathematica.

- Capasso, V. (1993). Mathematical Structure of Epidemic Systems. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 3-540-56526-4.

- Miller, J.C. (2012). "A note on the derivation of epidemic final sizes". Bulletin of Mathematical Biology 74 (9): section 4.1. doi:10.1007/s11538-012-9749-6. PMID 22829179. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3506030

- Miller, J.C. (2017). "Mathematical models of SIR disease spread with combined non-sexual and sexual transmission routes". Infectious Disease Modelling 2 (1): section 2.1.3. doi:10.1016/j.idm.2016.12.003. PMID 29928728. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=5963332

- Kermack, W. O.; McKendrick, A. G. (1927). "A Contribution to the Mathematical Theory of Epidemics". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Containing Papers of a Mathematical and Physical Character 115 (772): 700–721. doi:10.1098/rspa.1927.0118. Bibcode: 1927RSPSA.115..700K. https://dx.doi.org/10.1098%2Frspa.1927.0118

- Kendall, D. G. (1956). "Deterministic and stochastic epidemics in closed populations". Proceedings of the Third Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability: Contributions to Biology and Problems of Health 4: 149–165. doi:10.1525/9780520350717-011. ISBN 9780520350717. http://projecteuclid.org/euclid.bsmsp/1200502553.

- "A Density–Dependent Epidemiological Model for the Spread of Infectious Diseases". Liceo Journal of Higher Education Research 6 (2). 2 December 2010. doi:10.7828/ljher.v6i2.62. https://dx.doi.org/10.7828%2Fljher.v6i2.62

- May, Robert M.; Anderson, B. (1992-09-24) (in en). Infectious Diseases of Humans: Dynamics and Control (Revised ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198540403.

- Hethcote, Herbert W. (1989). "Three Basic Epidemiological Models". in Levin, Simon A.; Hallam, Thomas G.; Gross, Louis J.. Applied Mathematical Ecology. Biomathematics. 18. Berlin: Springer. pp. 119–144. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-61317-3_5. ISBN 3-540-19465-7. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2F978-3-642-61317-3_5

- (p. 19) The SI Model http://math.colgate.edu/~wweckesser/math312Spring06/handouts/IMM_SI_Model.pdf

- R. Parshani, S. Carmi, S. Havlin (2010). "Epidemic Threshold for the Susceptible-Infectious-Susceptible Model on Random Networks". Phys. Rev. Lett. 104 (25): 258701 (2010). doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.104.258701. PMID 20867419. Bibcode: 2010PhRvL.104y8701P. https://dx.doi.org/10.1103%2FPhysRevLett.104.258701

- The first and second differential equations are transformed and brought to the same form as for the SIR model above.

- Schlickeiser, Reinhard; Kröger, Martin (2021). "Analytical Modeling of the Temporal Evolution of Epidemics Outbreaks Accounting for Vaccinations" (in en). Physics 3 (2): 386. doi:10.3390/physics3020028. Bibcode: 2021Physi...3..386S. https://dx.doi.org/10.3390%2Fphysics3020028

- Hunziker, Patrick (2021-07-24). "Personalized-dose Covid-19 vaccination in a wave of virus Variants of Concern: Trading individual efficacy for societal benefit" (in en). Precision Nanomedicine 4 (3): 805–820. doi:10.33218/001c.26101. https://precisionnanomedicine.com/article/26101-personalized-dose-covid-19-vaccination-in-a-wave-of-virus-variants-of-concern-trading-individual-efficacy-for-societal-benefit.

- Noble, J.V. (1974). "Geographic and temporal development of plagues" (in en). Nature 250 (5469): 726–729. doi:10.1038/250726a0. PMID 4606583. Bibcode: 1974Natur.250..726N. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038%2F250726a0

- te Vrugt, Michael; Bickmann, Jens; Wittkowski, Raphael (2020). "Effects of social distancing and isolation on epidemic spreading modeled via dynamical density functional theory" (in en). Nature Communications 11 (1): 5576. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-19024-0. PMID 33149128. Bibcode: 2020NatCo..11.5576T. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=7643184

- Hunziker, Patrick (2021-07-24). "Personalized-dose Covid-19 vaccination in a wave of virus Variants of Concern: Trading individual efficacy for societal benefit" (in en). Precision Nanomedicine 4 (3): 805–820. doi:10.33218/001c.26101. https://precisionnanomedicine.com/article/26101-personalized-dose-covid-19-vaccination-in-a-wave-of-virus-variants-of-concern-trading-individual-efficacy-for-societal-benefit.

- Hunziker, Patrick (2021-03-07). "Vaccination strategies for minimizing loss of life in Covid-19 in a Europe lacking vaccines" (in en). medRxiv: 2021.01.29.21250747. doi:10.1101/2021.01.29.21250747. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.01.29.21250747v6.

- LD Valdez, LA Braunstein, S Havlin (2020). "Epidemic spreading on modular networks: The fear to declare a pandemic". Physical Review E 101 (3): 032309. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.101.032309. PMID 32289896. Bibcode: 2020PhRvE.101c2309V. https://dx.doi.org/10.1103%2FPhysRevE.101.032309

- Croccolo F. and Roman H.E. (2020). "Spreading of infections on random graphs: A percolation-type model for COVID-19". Chaos, Solitons & Fractals 139: 110077. doi:10.1016/j.chaos.2020.110077. PMID 32834619. Bibcode: 2020CSF...13910077C. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=7332959

- Gao, Shujing; Teng, Zhidong; Nieto, Juan J.; Torres, Angela (2007). "Analysis of an SIR Epidemic Model with Pulse Vaccination and Distributed Time Delay". Journal of Biomedicine and Biotechnology 2007: 64870. doi:10.1155/2007/64870. PMID 18322563. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2217597

- Brauer, F.; Castillo-Chávez, C. (2001). Mathematical Models in Population Biology and Epidemiology. NY: Springer. ISBN 0-387-98902-1.

- For more information on this type of model see Anderson, R. M., ed (1982). Population Dynamics of Infectious Diseases: Theory and Applications. London-New York: Chapman and Hall. ISBN 0-412-21610-8.

- Bartlett MS (1957). "Measles periodicity and community size". Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series A 120 (1): 48–70. doi:10.2307/2342553. https://dx.doi.org/10.2307%2F2342553

- May, Robert M.; Lloyd, Alun L. (2001-11-19). "Infection dynamics on scale-free networks". Physical Review E 64 (6): 066112. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.64.066112. PMID 11736241. Bibcode: 2001PhRvE..64f6112M. https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevE.64.066112.

- Pastor-Satorras, Romualdo; Vespignani, Alessandro (2001-04-02). "Epidemic Spreading in Scale-Free Networks". Physical Review Letters 86 (14): 3200–3203. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.86.3200. PMID 11290142. Bibcode: 2001PhRvL..86.3200P. https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevLett.86.3200.

- Newman, M. E. J. (2002-07-26). "Spread of epidemic disease on networks". Physical Review E 66 (1): 016128. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.66.016128. PMID 12241447. Bibcode: 2002PhRvE..66a6128N. https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevE.66.016128.

- Wong, Felix; Collins, James J. (2020-11-02). "Evidence that coronavirus superspreading is fat-tailed" (in en). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117 (47): 29416–29418. doi:10.1073/pnas.2018490117. ISSN 0027-8424. PMID 33139561. Bibcode: 2020PNAS..11729416W. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=7703634

- R Cohen, S Havlin, D Ben-Avraham (2003). "Efficient immunization strategies for computer networks and populations". Physical Review Letters 91 (24): 247901. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.91.247901. PMID 14683159. Bibcode: 2003PhRvL..91x7901C. https://dx.doi.org/10.1103%2FPhysRevLett.91.247901

- Y Liu, H Sanhedrai, GG Dong, LM Shekhtman, F Wang, SV Buldyrev, S. Havlin (2021). "Efficient network immunization under limited knowledge". National Science Review 8 (1). doi:10.1093/nsr/nwaa229. https://dx.doi.org/10.1093%2Fnsr%2Fnwaa229