| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sirius Huang | -- | 1973 | 2022-12-01 01:41:32 |

Video Upload Options

Gamma-Aminobutyric acid, or γ-aminobutyric acid /ˈɡæmə əˈmiːnoʊbjuːˈtɪrɪk ˈæsɪd/, or GABA /ˈɡæbə/, is the chief inhibitory neurotransmitter in the developmentally mature mammalian central nervous system. Its principal role is reducing neuronal excitability throughout the nervous system. GABA is sold as a dietary supplement in many countries. It has been traditionally thought that exogenous GABA (i.e. taken as a supplement) doesn't cross the blood-brain barrier, however data obtained from more current research indicates that it may be possible.

1. Function

1.1. Neurotransmitter

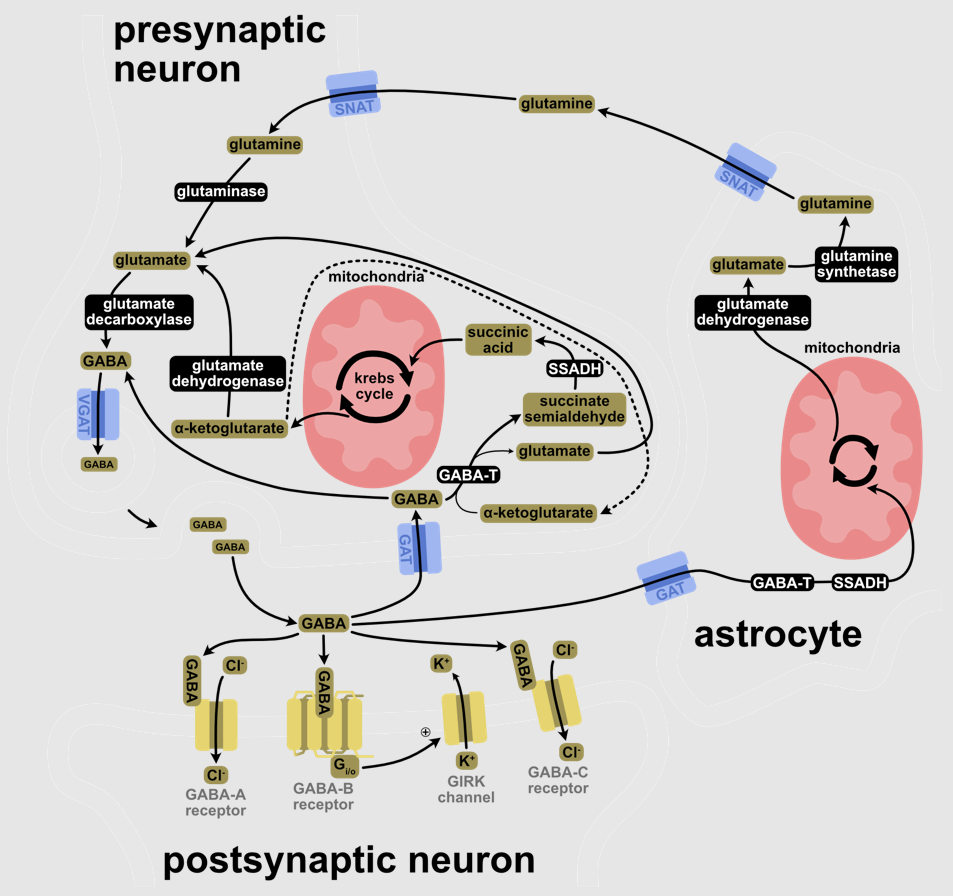

Two general classes of GABA receptor are known:[1]

- GABAA in which the receptor is part of a ligand-gated ion channel complex[2]

- GABAB metabotropic receptors, which are G protein-coupled receptors that open or close ion channels via intermediaries (G proteins)

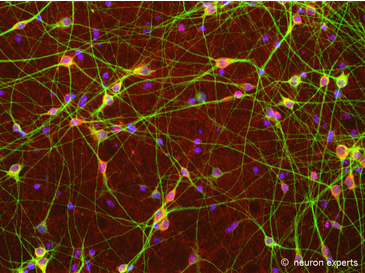

Neurons that produce GABA as their output are called GABAergic neurons, and have chiefly inhibitory action at receptors in the adult vertebrate. Medium spiny cells are a typical example of inhibitory central nervous system GABAergic cells. In contrast, GABA exhibits both excitatory and inhibitory actions in insects, mediating muscle activation at synapses between nerves and muscle cells, and also the stimulation of certain glands.[3] In mammals, some GABAergic neurons, such as chandelier cells, are also able to excite their glutamatergic counterparts.[4]

GABAA receptors are ligand-activated chloride channels: when activated by GABA, they allow the flow of chloride ions across the membrane of the cell.[5] Whether this chloride flow is depolarizing (makes the voltage across the cell's membrane less negative), shunting (has no effect on the cell's membrane potential), or inhibitory/hyperpolarizing (makes the cell's membrane more negative) depends on the direction of the flow of chloride. When net chloride flows out of the cell, GABA is depolarising; when chloride flows into the cell, GABA is inhibitory or hyperpolarizing. When the net flow of chloride is close to zero, the action of GABA is shunting. Shunting inhibition has no direct effect on the membrane potential of the cell; however, it reduces the effect of any coincident synaptic input by reducing the electrical resistance of the cell's membrane. Shunting inhibition can "override" the excitatory effect of depolarising GABA, resulting in overall inhibition even if the membrane potential becomes less negative. It was thought that a developmental switch in the molecular machinery controlling the concentration of chloride inside the cell changes the functional role of GABA between neonatal and adult stages. As the brain develops into adulthood, GABA's role changes from excitatory to inhibitory.[6]

1.2. Brain Development

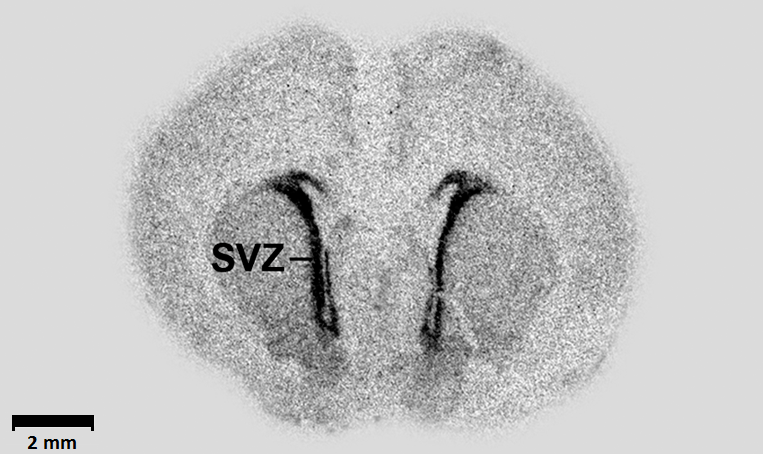

While GABA is an inhibitory transmitter in the mature brain, its actions were thought to be primarily excitatory in the developing brain.[6][7] The gradient of chloride was reported to be reversed in immature neurons, with its reversal potential higher than the resting membrane potential of the cell; activation of a GABA-A receptor thus leads to efflux of Cl− ions from the cell (that is, a depolarizing current). The differential gradient of chloride in immature neurons was shown to be primarily due to the higher concentration of NKCC1 co-transporters relative to KCC2 co-transporters in immature cells. GABAergic interneurons mature faster in the hippocampus and the GABA signalling machinery appears earlier than glutamatergic transmission. Thus, GABA is considered the major excitatory neurotransmitter in many regions of the brain before the maturation of glutamatergic synapses.[8]

In the developmental stages preceding the formation of synaptic contacts, GABA is synthesized by neurons and acts both as an autocrine (acting on the same cell) and paracrine (acting on nearby cells) signalling mediator.[9][10] The ganglionic eminences also contribute greatly to building up the GABAergic cortical cell population.[11]

GABA regulates the proliferation of neural progenitor cells,[12][13] the migration[14] and differentiation[15][16] the elongation of neurites[17] and the formation of synapses.[18]

GABA also regulates the growth of embryonic and neural stem cells. GABA can influence the development of neural progenitor cells via brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) expression.[19] GABA activates the GABAA receptor, causing cell cycle arrest in the S-phase, limiting growth.[20]

1.3. Beyond the Nervous System

Besides the nervous system, GABA is also produced at relatively high levels in the insulin-producing β-cells of the pancreas. The β-cells secrete GABA along with insulin and the GABA binds to GABA receptors on the neighboring islet α-cells and inhibits them from secreting glucagon (which would counteract insulin's effects).[22]

GABA can promote the replication and survival of β-cells[23][24][25] and also promote the conversion of α-cells to β-cells, which may lead to new treatments for diabetes.[26]

Alongside GABAergic mechanisms, GABA has also been detected in other peripheral tissues including intestines, stomach, Fallopian tubes, uterus, ovaries, testes, kidneys, urinary bladder, the lungs and liver, albeit at much lower levels than in neurons or β-cells.[27]

Experiments on mice have shown that hypothyroidism induced by fluoride poisoning can be halted by administering GABA. The test also found that the thyroid recovered naturally without further assistance after the Fluoride had been expelled by the GABA.[28]

Immune cells express receptors for GABA[29][30] and administration of GABA can suppress inflammatory immune responses and promote "regulatory" immune responses, such that GABA administration has been shown to inhibit autoimmune diseases in several animal models.[23][29][31][32]

In 2018, GABA has shown to regulate secretion of a greater number of cytokines. In plasma of T1D patients, levels of 26 cytokines are increased and of those, 16 are inhibited by GABA in the cell assays.[33]

In 2007, an excitatory GABAergic system was described in the airway epithelium. The system is activated by exposure to allergens and may participate in the mechanisms of asthma.[34] GABAergic systems have also been found in the testis[35] and in the eye lens.[36]

2. Structure and Conformation

GABA is found mostly as a zwitterion (i.e. with the carboxyl group deprotonated and the amino group protonated). Its conformation depends on its environment. In the gas phase, a highly folded conformation is strongly favored due to the electrostatic attraction between the two functional groups. The stabilization is about 50 kcal/mol, according to quantum chemistry calculations. In the solid state, an extended conformation is found, with a trans conformation at the amino end and a gauche conformation at the carboxyl end. This is due to the packing interactions with the neighboring molecules. In solution, five different conformations, some folded and some extended, are found as a result of solvation effects. The conformational flexibility of GABA is important for its biological function, as it has been found to bind to different receptors with different conformations. Many GABA analogues with pharmaceutical applications have more rigid structures in order to control the binding better.[37][38]

3. History

In 1883, GABA was first synthesized, and it was first known only as a plant and microbe metabolic product.[39]

In 1950, GABA was discovered as an integral part of the mammalian central nervous system.[39]

In 1959, it was shown that at an inhibitory synapse on crayfish muscle fibers GABA acts like stimulation of the inhibitory nerve. Both inhibition by nerve stimulation and by applied GABA are blocked by picrotoxin.[40]

4. Biosynthesis

GABA is primarily synthesized from glutamate via the enzyme glutamate decarboxylase (GAD) with pyridoxal phosphate (the active form of vitamin B6) as a cofactor. This process converts glutamate (the principal excitatory neurotransmitter) into GABA (the principal inhibitory neurotransmitter).[41][42]

GABA can also be synthesized from putrescine[43][44] by diamine oxidase and aldehyde dehydrogenase.[43]

Traditionally it was thought that exogenous GABA did not penetrate the blood–brain barrier,[45] however more current research[46] indicates that it may be possible, or that exogenous GABA (i.e. in the form of nutritional supplements) could exert GABAergic effects on the enteric nervous system which in turn stimulate endogenous GABA production. The direct involvement of GABA in the glutamate–glutamine cycle makes the question of whether GABA can penetrate the blood-brain barrier somewhat misleading, because both glutamate and glutamine can freely cross the barrier and convert to GABA within the brain.

5. Metabolism

GABA transaminase enzymes catalyze the conversion of 4-aminobutanoic acid (GABA) and 2-oxoglutarate (α-ketoglutarate) into succinic semialdehyde and glutamate. Succinic semialdehyde is then oxidized into succinic acid by succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase and as such enters the citric acid cycle as a usable source of energy.[47]

6. Pharmacology

Drugs that act as allosteric modulators of GABA receptors (known as GABA analogues or GABAergic drugs), or increase the available amount of GABA, typically have relaxing, anti-anxiety, and anti-convulsive effects (with equivalent efficacy to lamotrigine based on studies of mice).[48][49] Many of the substances below are known to cause anterograde amnesia and retrograde amnesia.[50]

In general, GABA does not cross the blood–brain barrier,[45] although certain areas of the brain that have no effective blood–brain barrier, such as the periventricular nucleus, can be reached by drugs such as systemically injected GABA.[51] At least one study suggests that orally administered GABA increases the amount of human growth hormone (HGH).[52] GABA directly injected to the brain has been reported to have both stimulatory and inhibitory effects on the production of growth hormone, depending on the physiology of the individual.[51] Certain pro-drugs of GABA (ex. picamilon) have been developed to permeate the blood–brain barrier, then separate into GABA and the carrier molecule once inside the brain. Prodrugs allow for a direct increase of GABA levels throughout all areas of the brain, in a manner following the distribution pattern of the pro-drug prior to metabolism.

GABA enhanced the catabolism of serotonin into N-acetylserotonin (the precursor of melatonin) in rats.[53] It is thus suspected that GABA is involved in the synthesis of melatonin and thus might exert regulatory effects on sleep and reproductive functions.[54]

7. Chemistry

Although in chemical terms, GABA is an amino acid (as it has both a primary amine and a carboxylic acid functional group), it is rarely referred to as such in the professional, scientific, or medical community. By convention the term "amino acid", when used without a qualifier, refers specifically to an alpha amino acid. GABA is not an alpha amino acid, meaning the amino group is not attached to the alpha carbon. Nor is it incorporated into proteins as are many alpha-amino acids.[55]

8. GABAergic Drugs

GABAA receptor ligands are shown in the following table[56]

| Activity at GABAA | Ligand |

|---|---|

| Orthosteric Agonist | Muscimol,[57] GABA,[57] gaboxadol (THIP),[57] isoguvacine, progabide, piperidine-4-sulfonic acid (partial agonist) |

| Positive allosteric modulators | Barbiturates,[58] benzodiazepines,[59] neuroactive steroids,[60] niacin/niacinamide,[61] nonbenzodiazepines (i.e. z-drugs, e.g. zolpidem, eszopiclone), etomidate,[62] etaqualone, alcohol (ethanol),[63][64][65] theanine , methaqualone, propofol, stiripentol,[66] and anaesthetics[57] (including volatile anaesthetics), glutethimide |

| Orthosteric (competitive) Antagonist | bicuculline,[57] gabazine,[67] thujone,[68] flumazenil[69] |

| Uncompetitive antagonist (e.g. channel blocker) | picrotoxin , cicutoxin |

| Negative allosteric modulators | neuroactive steroids (Pregnenolone sulfate ), furosemide, oenanthotoxin, amentoflavone |

Additionally, carisoprodol is an enhancer of GABAA activity . Ro15-4513 is a reducer of GABAA activity .

GABAergic pro-drugs include chloral hydrate, which is metabolised to trichloroethanol,[70] which then acts via the GABAA receptor.[71]

Skullcap and valerian are plants containing GABAergic substances . Furthermore, the plant kava contains GABAergic compounds, including kavain, dihydrokavain, methysticin, dihydromethysticin and yangonin.[72]

Other GABAergic modulators include:

- GABAB receptor ligands.

- Agonists: baclofen, propofol, GHB,[73] phenibut.

- Antagonists: phaclofen, saclofen.

- GABA reuptake inhibitors: deramciclane, hyperforin, tiagabine.

- GABA transaminase inhibitors: gabaculine, phenelzine, valproate, vigabatrin, lemon balm (Melissa officinalis).[74]

- GABA analogues: pregabalin, gabapentin,[75] picamilon, progabide

9. In Plants

GABA is also found in plants.[76][77] It is the most abundant amino acid in the apoplast of tomatoes.[78] Evidence also suggests a role in cell signalling in plants.[79][80]

The science team at GABA Labs has produced a botanical ingredient which was released to the market in the form of the drink "Sentia" in January 2021 as a "botanical spirit" that could mimic some of the effects of alcohol (ethanol) - primarily "conviviality" - in humans (impacting the GABA receptor) while avoiding the negative health impacts of alcohol.[81]

References

- Generalized Non-Convulsive Epilepsy: Focus on GABA-B Receptors, C. Marescaux, M. Vergnes, R. Bernasconi https://books.google.com/books?id=YggrBgAAQBAJ&pg=PT80

- Phulera, Swastik; Zhu, Hongtao; Yu, Jie; Claxton, Derek P; Yoder, Nate; Yoshioka, Craig; Gouaux, Eric (2018-07-25). "Cryo-EM structure of the benzodiazepine-sensitive α1β1γ2S tri-heteromeric GABAA receptor in complex with GABA" (in en). eLife 7: e39383. doi:10.7554/eLife.39383. ISSN 2050-084X. PMID 30044221. PMC 6086659. https://elifesciences.org/articles/39383.

- "A point mutation in a Drosophila GABA receptor confers insecticide resistance". Nature 363 (6428): 449–51. June 1993. doi:10.1038/363449a0. PMID 8389005. Bibcode: 1993Natur.363..449F. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038%2F363449a0

- "Excitatory effect of GABAergic axo-axonic cells in cortical microcircuits". Science 311 (5758): 233–235. January 2006. doi:10.1126/science.1121325. PMID 16410524. Bibcode: 2006Sci...311..233S. https://dx.doi.org/10.1126%2Fscience.1121325

- Phulera, Swastik; Zhu, Hongtao; Yu, Jie; Claxton, Derek P; Yoder, Nate; Yoshioka, Craig; Gouaux, Eric (2018-07-25). "Cryo-EM structure of the benzodiazepine-sensitive α1β1γ2S tri-heteromeric GABAA receptor in complex with GABA" (in en). eLife 7: e39383. doi:10.7554/eLife.39383. ISSN 2050-084X. PMID 30044221. PMC 6086659. https://elifesciences.org/articles/39383.

- "The role and the mechanism of γ-aminobutyric acid during central nervous system development". Neurosci Bull 24 (3): 195–200. June 2008. doi:10.1007/s12264-008-0109-3. PMID 18500393. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=5552538

- "GABA: a pioneer transmitter that excites immature neurons and generates primitive oscillations". Physiol. Rev. 87 (4): 1215–1284. October 2007. doi:10.1152/physrev.00017.2006. PMID 17928584. https://dx.doi.org/10.1152%2Fphysrev.00017.2006

- The Glutamate/GABA-Glutamine Cycle: Amino Acid Neurotransmitter Homeostasis, Arne Schousboe, Ursula Sonnewald https://books.google.com/books?id=rrKVDQAAQBAJ&pg=PA311

- Neuroscience (4th ed.). Sunderland, Mass: Sinauer. 2007. pp. 135, box 6D. ISBN 978-0-87893-697-7. https://archive.org/details/neuroscienceissu00purv.

- "The role of GABA in the early neuronal development". GABA in Autism and Related Disorders. International Review of Neurobiology. 71. 2005. 27–62. doi:10.1016/S0074-7742(05)71002-3. ISBN 9780123668721. https://books.google.com/books?id=IUb5ewXY09YC&pg=PA27.

- "A long, remarkable journey: tangential migration in the telencephalon". Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2 (11): 780–90. November 2001. doi:10.1038/35097509. PMID 11715055. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038%2F35097509

- "GABA and glutamate depolarize cortical progenitor cells and inhibit DNA synthesis". Neuron 15 (6): 1287–1298. December 1995. doi:10.1016/0896-6273(95)90008-X. PMID 8845153. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2F0896-6273%2895%2990008-X

- "Differential modulation of proliferation in the neocortical ventricular and subventricular zones". J. Neurosci. 20 (15): 5764–74. August 2000. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-15-05764.2000. PMID 10908617. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3823557

- "Differential response of cortical plate and ventricular zone cells to GABA as a migration stimulus". J. Neurosci. 18 (16): 6378–87. August 1998. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-16-06378.1998. PMID 9698329. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=6793175

- "GABA itself promotes the developmental switch of neuronal GABAergic responses from excitation to inhibition". Cell 105 (4): 521–32. May 2001. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00341-5. PMID 11371348. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2FS0092-8674%2801%2900341-5

- "Involvement of GABAA receptors in the outgrowth of cultured hippocampal neurons". Neurosci. Lett. 152 (1–2): 150–154. April 1993. doi:10.1016/0304-3940(93)90505-F. PMID 8390627. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2F0304-3940%2893%2990505-F

- "GABA expression dominates neuronal lineage progression in the embryonic rat neocortex and facilitates neurite outgrowth via GABA(A) autoreceptor/Cl− channels". J. Neurosci. 21 (7): 2343–60. April 2001. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-07-02343.2001. PMID 11264309. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=6762405

- "Excitatory actions of gaba during development: the nature of the nurture". Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 3 (9): 728–739. September 2002. doi:10.1038/nrn920. PMID 12209121. http://www.hal.inserm.fr/inserm-00484852.

- "Excitatory actions of GABA increase BDNF expression via a MAPK-CREB-dependent mechanism—a positive feedback circuit in developing neurons". J. Neurophysiol. 88 (2): 1005–15. August 2002. doi:10.1152/jn.2002.88.2.1005. PMID 12163549. https://dx.doi.org/10.1152%2Fjn.2002.88.2.1005

- "GABA regulates stem cell proliferation before nervous system formation". Epilepsy Curr 8 (5): 137–9. 2008. doi:10.1111/j.1535-7511.2008.00270.x. PMID 18852839. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2566617

- Reh, Thomas A., ed (2009). "Adult and embryonic GAD transcripts are spatiotemporally regulated during postnatal development in the rat brain". PLoS ONE 4 (2): e4371. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0004371. PMID 19190758. Bibcode: 2009PLoSO...4.4371P. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2629816

- "Glucose-inhibition of glucagon secretion involves activation of GABAA-receptor chloride channels". Nature 341 (6239): 233–6. 1989. doi:10.1038/341233a0. PMID 2550826. Bibcode: 1989Natur.341..233R. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038%2F341233a0

- "GABA exerts protective and regenerative effects on islet beta cells and reverses diabetes". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108 (28): 11692–7. 2011. doi:10.1073/pnas.1102715108. PMID 21709230. Bibcode: 2011PNAS..10811692S. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3136292

- "γ-Aminobutyric acid regulates both the survival and replication of human β-cells". Diabetes 62 (11): 3760–5. 2013. doi:10.2337/db13-0931. PMID 23995958. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3806626

- "GABA promotes human β-cell proliferation and modulates glucose homeostasis". Diabetes 63 (12): 4197–205. 2014. doi:10.2337/db14-0153. PMID 25008178. https://dx.doi.org/10.2337%2Fdb14-0153

- "Long-Term GABA Administration Induces Alpha Cell-Mediated Beta-like Cell Neogenesis". Cell 168 (1–2): 73–85.e11. 2017. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2016.11.002. PMID 27916274. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.cell.2016.11.002

- "γ-Aminobutyric acid outside the mammalian brain". J. Neurochem. 54 (2): 363–72. February 1990. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb01882.x. PMID 2405103. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2Fj.1471-4159.1990.tb01882.x

- "γ-Aminobutyric acid ameliorates fluoride-induced hypothyroidism in male Kunming mice". Life Sciences 146: 1–7. 2016. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2015.12.041. PMID 26724496. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.lfs.2015.12.041

- "GABAA receptors mediate inhibition of T cell responses". J. Neuroimmunol. 96 (1): 21–8. 1999. doi:10.1016/s0165-5728(98)00264-1. PMID 10227421. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fs0165-5728%2898%2900264-1

- "Different subtypes of GABA-A receptors are expressed in human, mouse and rat T lymphocytes". PLOS ONE 7 (8): e42959. 2012. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0042959. PMID 22927941. Bibcode: 2012PLoSO...742959M. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3424250

- "Gamma-aminobutyric acid inhibits T cell autoimmunity and the development of inflammatory responses in a mouse type 1 diabetes model". J. Immunol. 173 (8): 5298–304. 2004. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.173.8.5298. PMID 15470076. https://dx.doi.org/10.4049%2Fjimmunol.173.8.5298

- "Oral GABA treatment downregulates inflammatory responses in a mouse model of rheumatoid arthritis". Autoimmunity 44 (6): 465–70. 2011. doi:10.3109/08916934.2011.571223. PMID 21604972. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=5787624

- "+ T Cells and Is Immunosuppressive in Type 1 Diabetes". EBioMedicine 30: 283–294. April 2018. doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.03.019. PMID 29627388. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=5952354

- "A GABAergic system in airway epithelium is essential for mucus overproduction in asthma". Nat. Med. 13 (7): 862–7. July 2007. doi:10.1038/nm1604. PMID 17589520. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038%2Fnm1604

- The Leydig cell in health and disease. Humana Press. 2007. ISBN 978-1-58829-754-9.

- "GAD isoforms exhibit distinct spatiotemporal expression patterns in the developing mouse lens: correlation with Dlx2 and Dlx5". Dev. Dyn. 236 (12): 3532–44. December 2007. doi:10.1002/dvdy.21361. PMID 17969168. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002%2Fdvdy.21361

- "Conformation, electrostatic potential and pharmacophoric pattern of GABA (γ-aminobutyric acid) and several GABA inhibitors". Journal of Molecular Structure: THEOCHEM 180: 125–140. 1988. doi:10.1016/0166-1280(88)80084-8. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2F0166-1280%2888%2980084-8

- Molecular Orbital Calculations for Amino Acids and Peptides. Birkhäuser. 2000. ISBN 978-0-8176-3893-1.

- The Biochemical Basis of Neuropharmacology. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press. 2003. pp. 106. ISBN 978-0-19-514008-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=vNaM55VDoF8C&pg=PA106.

- W. G. Van der Kloot; J. Robbins (1959). "The effects of GABA and picrotoxin on the junctional potential and the contraction of crayfish muscle". Experientia 15: 36.

- "GABA and glutamate in the human brain". Neuroscientist 8 (6): 562–573. December 2002. doi:10.1177/1073858402238515. PMID 12467378. https://dx.doi.org/10.1177%2F1073858402238515

- "GABA: homeostatic and pharmacological aspects". Gaba and the Basal Ganglia - from Molecules to Systems. Progress in Brain Research. 160. 2007. 9–19. doi:10.1016/S0079-6123(06)60002-2. ISBN 978-0-444-52184-2. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2FS0079-6123%2806%2960002-2

- Krantis, Anthony (2000-12-01). "GABA in the Mammalian Enteric Nervous System". Physiology 15 (6): 284–290. doi:10.1152/physiologyonline.2000.15.6.284. ISSN 1548-9213. PMID 11390928. https://dx.doi.org/10.1152%2Fphysiologyonline.2000.15.6.284

- Sequerra, E. B.; Gardino, P.; Hedin-Pereira, C.; de Mello, F. G. (2007-05-11). "Putrescine as an important source of GABA in the postnatal rat subventricular zone". Neuroscience 146 (2): 489–493. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.01.062. ISSN 0306-4522. PMID 17395389. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.neuroscience.2007.01.062

- "Blood–brain barrier to H3-γ-aminobutyric acid in normal and amino oxyacetic acid-treated animals". Neuropharmacology 10 (1): 103–108. January 1971. doi:10.1016/0028-3908(71)90013-X. PMID 5569303. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2F0028-3908%2871%2990013-X

- "Neurotransmitters as food supplements: the effects of GABA on brain and behavior". Front Psychol 6: 1520. 2015. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01520. PMID 26500584. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=4594160

- "The Metabolism and Functions of γ-Aminobutyric Acid". Plant Physiol. 115 (1): 1–5. September 1997. doi:10.1104/pp.115.1.1. PMID 12223787. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=158453

- "Glutamate- and GABA-based CNS therapeutics". Curr Opin Pharmacol 6 (1): 7–17. February 2006. doi:10.1016/j.coph.2005.11.005. PMID 16377242. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.coph.2005.11.005

- "A pharmacological link between epilepsy and anxiety?". Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 22 (10): 491–3. October 2001. doi:10.1016/S0165-6147(00)01807-1. PMID 11583788. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2FS0165-6147%2800%2901807-1

- "Mechanisms of actions of inhaled anesthetics". N. Engl. J. Med. 348 (21): 2110–24. May 2003. doi:10.1056/NEJMra021261. PMID 12761368. https://dx.doi.org/10.1056%2FNEJMra021261

- "Neuroendocrine control of growth hormone secretion". Physiol. Rev. 79 (2): 511–607. April 1999. doi:10.1152/physrev.1999.79.2.511. PMID 10221989. https://dx.doi.org/10.1152%2Fphysrev.1999.79.2.511

- "Growth hormone isoform responses to GABA ingestion at rest and after exercise". Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 40 (1): 104–10. January 2008. doi:10.1249/mss.0b013e318158b518. PMID 18091016. https://dx.doi.org/10.1249%2Fmss.0b013e318158b518

- "The influence of GABA on the synthesis of N-acetylserotonin, melatonin, O-acetyl-5-hydroxytryptophol and O-acetyl-5-methoxytryptophol in the pineal gland of the male Wistar rat". Reproduction, Nutrition, Development 23 (1): 151–60. 1983. doi:10.1051/rnd:19830114. PMID 6844712. https://dx.doi.org/10.1051%2Frnd%3A19830114

- "Sexually dimorphic modulation of GABA(A) receptor currents by melatonin in rats gonadotropin–releasing hormone neurons". J Physiol Sci 58 (5): 317–322. 2008. doi:10.2170/physiolsci.rp006208. PMID 18834560. https://dx.doi.org/10.2170%2Fphysiolsci.rp006208

- The Brain, the Nervous System, and Their Diseases [3 volumes], Jennifer L. Hellier https://books.google.com/books?id=SDi2BQAAQBAJ&pg=RA1-PA435

- Many more GABAA ligands are listed at Template:GABA receptor modulators and at GABAA receptor

- "GABA a Receptors and the Diversity in their Structure and Pharmacology". GABAA Receptors and the Diversity in their Structure and Pharmacology. Advances in Pharmacology. 79. 2017. pp. 1–34. doi:10.1016/bs.apha.2017.03.003. ISBN 9780128104132. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fbs.apha.2017.03.003

- null

- "GABA and glycine". Basic Neurochemistry: Molecular, Cellular and Medical Aspects (7th ed.). Elsevier. 2006. pp. 291–302. ISBN 978-0-12-088397-4. https://archive.org/details/basicneurochemis00sieg_572.

- (a) "Neurosteroid modulation of synaptic and extrasynaptic GABA(A) receptors". Pharmacology & Therapeutics 116 (1): 20–34. October 2007. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.03.007. PMID 17531325. http://www.journals.elsevier.com/pharmacology-and-therapeutics. ; (b) "Endogenous neurosteroids regulate GABAA receptors through two discrete transmembrane sites". Nature 444 (7118): 486–9. November 2006. doi:10.1038/nature05324. PMID 17108970. Bibcode: 2006Natur.444..486H. ; (c)"Characterization of brain neurons that express enzymes mediating neurosteroid biosynthesis". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 103 (39): 14602–7. September 2006. doi:10.1073/pnas.0606544103. PMID 16984997. Bibcode: 2006PNAS..10314602A. ; (d) "Neurosteroid access to the GABAA receptor". The Journal of Neuroscience 25 (50): 11605–13. December 2005. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4173-05.2005. PMID 16354918. ; (e) "Neurosteroids: endogenous regulators of the GABA(A) receptor". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience 6 (7): 565–75. July 2005. doi:10.1038/nrn1703. PMID 15959466. ; (f) "Fluoxetine and norfluoxetine stereospecifically and selectively increase brain neurosteroid content at doses that are inactive on 5-HT reuptake". Psychopharmacology 186 (3): 362–72. June 2006. doi:10.1007/s00213-005-0213-2. PMID 16432684. ; (g) "Steroids, neuroactive steroids and neurosteroids in psychopathology". Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry 29 (2): 169–92. February 2005. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2004.11.001. PMID 15694225. ; (h) "Neurosteroids: biochemistry and clinical significance". Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism 13 (1): 35–43. 2002. doi:10.1016/S1043-2760(01)00503-3. PMID 11750861. ; (i) "Neurosteroids act on recombinant human GABAA receptors". Neuron 4 (5): 759–65. May 1990. doi:10.1016/0896-6273(90)90202-Q. PMID 2160838. ; (j) "Steroid hormone metabolites are barbiturate-like modulators of the GABA receptor". Science 232 (4753): 1004–7. May 1986. doi:10.1126/science.2422758. PMID 2422758. Bibcode: 1986Sci...232.1004D. https://zenodo.org/record/1230988. ; (k) "Neurosteroids — Endogenous Regulators of Seizure Susceptibility and Role in the Treatment of Epilepsy". Jasper's Basic Mechanisms of the Epilepsies [Internet]. 4th edition. Bethesda (MD): National Center for Biotechnology Information (US). National Center for Biotechnology Information (US). 2012. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK98218/.

- Toraskar, Mrunmayee; Pratima R.P. Singh; Shashank Neve (2010). "STUDY OF GABAERGIC AGONISTS". Deccan Journal of Pharmacology 1 (2): 56–69. http://www.ijdpls.com/uploaded/journal_files/120402040442.pdf. Retrieved 2019-04-01.

- Vanlersberghe, C; Camu, F (2008). Etomidate and other non-barbiturates. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. 182. pp. 267–82. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-74806-9_13. ISBN 978-3-540-72813-9. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2F978-3-540-74806-9_13

- "γ-aminobutyric acid B receptor 1 mediates behavior-impairing actions of alcohol in Drosophila: adult RNA interference and pharmacological evidence". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100 (9): 5485–5490. 2003. doi:10.1073/pnas.0830111100. PMID 12692303. Bibcode: 2003PNAS..100.5485D. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=154371

- "Sites of alcohol and volatile anaesthetic action on GABAA and glycine receptors". Nature 389 (6649): 385–389. 1997. doi:10.1038/38738. PMID 9311780. Bibcode: 1997Natur.389..385M. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038%2F38738

- "From gene to behavior and back again: new perspectives on GABAAreceptor subunit selectivity of alcohol actions". Adv. Pharmacol. 54 (8): 1581–1602. 2006. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2004.07.023. PMID 17175815. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.bcp.2004.07.023

- "The anti-convulsant stiripentol acts directly on the GABA(A) receptor as a positive allosteric modulator". Neuropharmacology 56 (1): 190–7. January 2009. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.06.004. PMID 18585399. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2665930

- Ueno, S; Bracamontes, J; Zorumski, C; Weiss, DS; Steinbach, JH (1997). "Bicuculline and gabazine are allosteric inhibitors of channel opening of the GABAA receptor". The Journal of Neuroscience 17 (2): 625–34. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.17-02-00625.1997. PMID 8987785. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=6573228

- Olsen RW (April 2000). "Absinthe and gamma-aminobutyric acid receptors". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97 (9): 4417–8. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.9.4417. PMID 10781032. Bibcode: 2000PNAS...97.4417O. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=34311

- Whitwam, J. G.; Amrein, R. (1995-01-01). "Pharmacology of flumazenil". Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica. Supplementum 108: 3–14. doi:10.1111/j.1399-6576.1995.tb04374.x. ISSN 0515-2720. PMID 8693922. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2Fj.1399-6576.1995.tb04374.x

- Jira, Reinhard; Kopp, Erwin; McKusick, Blaine C.; Röderer, Gerhard; Bosch, Axel; Fleischmann, Gerald. "Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a06_527.pub2. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002%2F14356007.a06_527.pub2

- Lu, J.; Greco, M. A. (2006). "Sleep circuitry and the hypnotic mechanism of GABAA drugs". Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine 2 (2): S19–S26. doi:10.5664/jcsm.26527. PMID 17557503. https://dx.doi.org/10.5664%2Fjcsm.26527

- "Therapeutic potential of kava in the treatment of anxiety disorders". CNS Drugs 16 (11): 731–43. 2002. doi:10.2165/00023210-200216110-00002. PMID 12383029. https://dx.doi.org/10.2165%2F00023210-200216110-00002

- "Drosophila GABAB receptors are involved in behavioral effects of gamma-hydroxybutyric acid (GHB)". Eur. J. Pharmacol. 519 (3): 246–252. 2005. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.07.016. PMID 16129424. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.ejphar.2005.07.016

- "Bioassay-guided fractionation of lemon balm (Melissa officinalis L.) using an in vitro measure of GABA transaminase activity". Phytother Res 23 (8): 1075–81. August 2009. doi:10.1002/ptr.2712. PMID 19165747. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002%2Fptr.2712

- "Gabapentin, A GABA analogue, enhances cognitive performance in mice". Neuroscience Letters 492 (2): 124–8. 2011. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2011.01.072. PMID 21296127. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.neulet.2011.01.072

- "GABA signalling modulates plant growth by directly regulating the activity of plant-specific anion transporters". Nat Commun 6: 7879. 2015. doi:10.1038/ncomms8879. PMID 26219411. Bibcode: 2015NatCo...6.7879R. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=4532832

- "γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA) signalling in plants". Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 74 (9): 1577–1603. 2016. doi:10.1007/s00018-016-2415-7. PMID 27838745. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2Fs00018-016-2415-7

- "Mutations in γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) transaminase genes in plants or Pseudomonas syringae reduce bacterial virulence". Plant J. 64 (2): 318–30. October 2010. doi:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04327.x. PMID 21070411. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2Fj.1365-313X.2010.04327.x

- "GABA in plants: just a metabolite?". Trends Plant Sci. 9 (3): 110–5. March 2004. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2004.01.006. PMID 15003233. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.tplants.2004.01.006

- "Does GABA Act as a Signal in Plants?: Hints from Molecular Studies". Plant Signal Behav 2 (5): 408–9. September 2007. doi:10.4161/psb.2.5.4335. PMID 19704616. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2634229

- Ducharme, Jamie (2021-12-28). "Can Synthetic Alcohol Make Drinking Safer? Experts Doubt It" (in en). https://time.com/6131012/synthetic-alcohol-health-benefits/.