| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Camila Xu | -- | 5679 | 2022-12-01 01:41:49 |

Video Upload Options

Gaulish was an ancient Celtic language that was spoken in parts of Continental Europe before and during the period of the Roman Empire. In the narrow sense, Gaulish was the language spoken by the Celtic inhabitants of Gaul (modern-day France, Luxembourg, Belgium, most of Switzerland, Northern Italy, as well as the parts of the Netherlands and Germany on the west bank of the Rhine). In a wider sense, it also comprises varieties of Celtic that were spoken across much of central Europe ("Noric"), parts of the Balkans, and Anatolia ("Galatian"), which are thought to have been closely related. The more divergent Lepontic of Northern Italy has also sometimes been subsumed under Gaulish. Together with Lepontic and the Celtiberian language spoken in the Iberian Peninsula, Gaulish helps form the geographic group of Continental Celtic languages. The precise linguistic relationships among them, as well as between them and the modern Insular Celtic languages, are uncertain and a matter of ongoing debate because of their sparse attestation. Gaulish is found in some 800 (often fragmentary) inscriptions including calendars, pottery accounts, funeral monuments, short dedications to gods, coin inscriptions, statements of ownership, and other texts, possibly curse tablets. Gaulish texts were first written in the Greek alphabet in southern France and in a variety of the Old Italic script in northern Italy. After the Roman conquest of those regions, writing shifted to the use of the Latin alphabet. During his conquest of Gaul, Caesar reported that the Helvetii were in possession of documents in the Greek script, and all Gaulish coins used the Greek script until about 50 BC. Gaulish in Western Europe was supplanted by Vulgar Latin and various Germanic languages from around the 5th century AD onwards. It is thought to have gone extinct some time around the late 6th century.

1. Classification

It is estimated that during the Bronze Age, Proto-Celtic started fragmenting into distinct languages, including Celtiberian and Gaulish.[1] As a result of the expansion of Celtic tribes during the 4th and 3rd centuries BC, closely related varieties of Celtic came to be spoken in a vast arc extending from present-day Britain and France through the Alpine region and Pannonia in central Europe, and into parts of the Balkans and Anatolia. Their precise linguistic relationships are uncertain because of the fragmentary nature of the evidence.

The Gaulish varieties of central and eastern Europe and of Anatolia (known as Noric and Galatian, respectively) are barely attested, but from what little is known of them it appears that they were still quite similar to those of Gaul and can be considered dialects of a single language.[2] Among those regions where substantial inscriptional evidence exists, three varieties are usually distinguished.

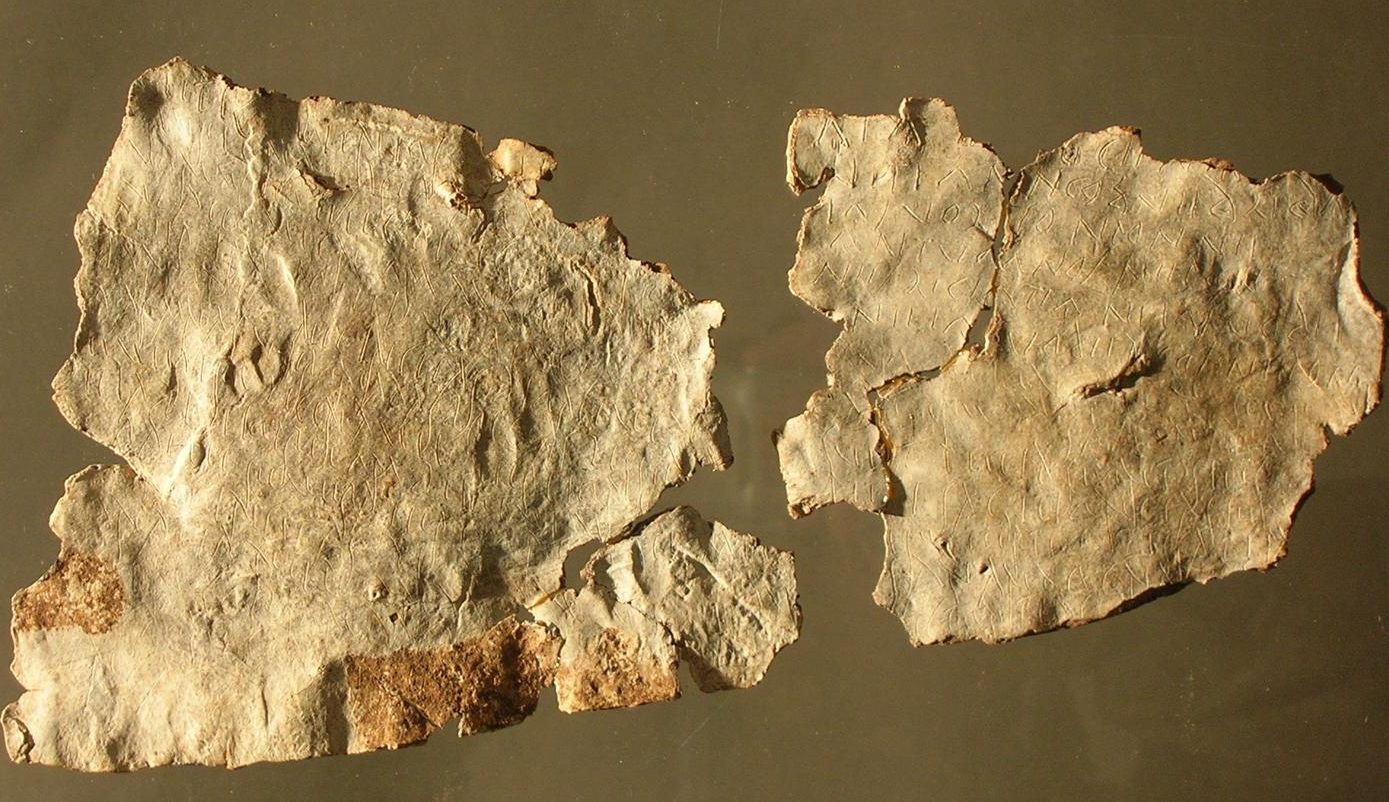

- Lepontic, attested from a small area on the southern slopes of the Alps, around the present-day Swiss town of Lugano, is the oldest Celtic language known to have been written, with inscriptions in a variant of the Old Italic script appearing circa 600 BC. It has been described as either an "early dialect of an outlying form of Gaulish" or a separate Continental Celtic language.[3]

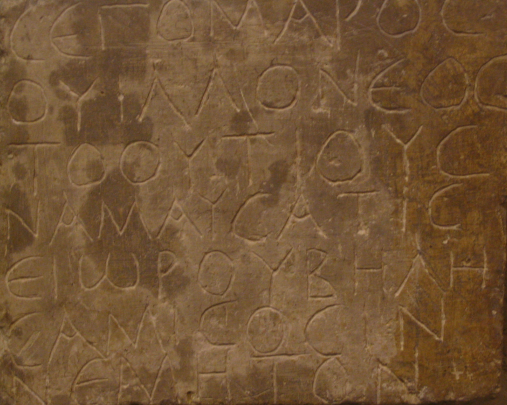

- Attestations of Gaulish proper in present-day France are known as "Transalpine Gaulish". Its written record begins in the 3rd century BC with inscriptions in the Greek alphabet, found mainly in the Rhône area of southern France, where Greek cultural influence was present via the colony of Massilia, founded circa 600 BC. After the Roman conquest of Gaul (58–50 BC), the writing of Gaulish shifted to the Latin alphabet.

- Finally, there are a small number of inscriptions from the second and first centuries BC in Cisalpine Gaul (modern northern Italy), which share the same archaic alphabet as the Lepontic inscriptions but are found outside the Lepontic area proper. As they were written after the time of the Gaulish conquest of Cisalpine Gaul, they are usually identified as "Cisalpine Gaulish". They share some linguistic features both with Lepontic and with Transalpine Gaulish; for instance, both Lepontic and Cisalpine Gaulish simplify the consonant clusters -nd- and -χs- to -nn- and -ss- respectively, while both Cisalpine and Transalpine Gaulish replace inherited word-final -m with -n.[4] Scholars have debated to what extent the distinctive features of Lepontic reflect merely its earlier origin or a genuine genealogical split, and to what extent Cisalpine Gaulish should be seen as a continuation of Lepontic or an independent offshoot of mainstream Transalpine Gaulish.

The relationship between Gaulish and the other Celtic languages is also subject to debate. Most scholars today agree that Celtiberian was the first to branch off from the remaining Celtic languages.[5] Gaulish, situated in the centre of the Celtic language area, shares with the neighbouring Brittonic languages of Great Britain, the change of the Indo-European labialized voiceless velar stop /kʷ/ > /p/, whereas both Celtiberian in the south and Goidelic in Ireland retain /kʷ/. Taking this as the primary genealogical isogloss, some scholars see the Celtic languages to be divided into a "q-Celtic" group and a "p-Celtic" group, in which the p-Celtic languages Gaulish and Brittonic form a common "Gallo-Brittonic" branch. Other scholars place more emphasis on shared innovations between Brittonic and Goidelic and group these together as an Insular Celtic branch. (Sims-Williams 2007) discusses a composite model, in which the Continental and Insular varieties are seen as part of a dialect continuum, with genealogical splits and areal innovations intersecting.[6]

2. History

2.1. Early Period

Although Gaulish personal names written by Gauls in the Greek alphabet are attested from the region surrounding Massalia by the 3rd century BC, the first true inscriptions in the Gaulish language appeared in the 2nd century BC.[7][8]

At least 13 references to Gaulish speech and Gaulish writing can be found in Greek and Latin writers of antiquity. The word "Gaulish" (gallicum) as a language term is first explicitly used in the Appendix Vergiliana in a poem referring to Gaulish letters of the alphabet.[9] Julius Caesar reported in his Commentarii de Bello Gallico of 58 BC that the Celts/Gauls and their language are separated from the neighboring Aquitanians and Belgae by the rivers Garonne and Seine/Marne, respectively.[10] Caesar relates that census accounts written in the Greek alphabet were found among the Helvetii.[11] He also notes that as of 53 BC the Gaulish druids used the Greek alphabet for private and public transactions, with the important exception of druidic doctrines, which could only be memorised and were not allowed to be written down.[12] According to the Recueil des Inscriptions Gauloises, nearly three quarters of Gaulish inscriptions (disregarding coins) are in the Greek alphabet. Later inscriptions dating to Roman Gaul are mostly in the Latin alphabet and have been found principally in central France.[13]

2.2. Roman Period

Latin was quickly adopted by the Gaulish aristocracy after the Roman conquest to maintain their elite power and influence,[14] trilingualism in southern Gaul being noted as early as the 1st century BC.[15]

Early references to Gaulish in Gaul tend to be made in the context of problems with Greek or Latin fluency until around 400, whereas after c. 450, Gaulish begins to be mentioned in contexts where Latin has replaced "Gaulish" or "Celtic" (whatever the authors meant by those terms), though at first these only concerned the upper classes. For Galatia (Anatolia), there is no source explicitly indicating a 5th century language replacement:

- During the last quarter of the 2nd century, Irenaeus, bishop of Lugdunum (present-day Lyon), apologises for his inadequate Greek, being "resident among the Keltae and accustomed for the most part to use a barbarous dialect".[16]

- According to the Vita Sancti Symphoriani, Symphorian of Augustodunum (present-day Autun) was executed on 22 August 178 for his Christian faith. While he was being led to his execution, "his venerable mother admonished him from the wall assiduously and notable to all (?), saying in the Gaulish speech: Son, son, Symphorianus, think of your God!" (uenerabilis mater sua de muro sedula et nota illum uoce Gallica monuit dicens: 'nate, nate Synforiane, mentobeto to diuo' [17]). The Gaulish sentence has been transmitted in a corrupt state in the various manuscripts; as it stands, it has been reconstructed by Thurneysen. According to David Stifter (2012), *mentobeto looks like a Proto-Romance verb derived from Latin mens, mentis ‘mind’ and habere ‘to have’, and it cannot be excluded that the whole utterance is an early variant of Romance, or a mixture of Romance and Gaulish, instead of being an instance of pure Gaulish. On the other hand, nate is attested in Gaulish (for example in Endlicher's Glossary[18]), and the author of the Vita Sancti Symphoriani, whether or not fluent in Gaulish, evidently expects a non-Latin language to have been spoken at the time.

- The Latin author Aulus Gellius (c. 180) mentions Gaulish alongside the Etruscan language in one anecdote, indicating that his listeners had heard of these languages, but would not understand a word of either.[19]

- The Roman History by Cassius Dio (written AD 207-229) may imply that Cis- and Transalpine Gauls spoke the same language, as can be deduced from the following passages: (1) Book XIII mentions the principle that named tribes have a common government and a common speech, otherwise the population of a region is summarised by a geographic term, as in the case of the Spanish/Iberians.[20] (2) In Books XII and XIV, Gauls between the Pyrenees and the River Po are stated to consider themselves kinsmen.[21][22] (3) In Book XLVI, Cassius Dio explains that the defining difference between Cis- and Transalpine Gauls is the length of hair and the style of clothes (i.e., he does not mention any language difference), the Cisalpine Gauls having adopted shorter hair and the Roman toga at an early date (Gallia Togata).[23] Potentially in contrast, Caesar described the river Rhone as a frontier between the Celts and provincia nostra.[10]

- In the Digesta XXXII, 11 of Ulpian (AD 222–228) it is decreed that fideicommissa (testamentary provisions) may also be composed in Gaulish.[24]

- Writing at some point between c. AD 378 and AD 395, the Latin poet and scholar Decimus Magnus Ausonius, from Burdigala (present-day Bordeaux), characterizes his deceased father Iulius's ability to speak Latin as inpromptus, "halting, not fluent"; in Attic Greek, Iulius felt sufficiently eloquent.[25] This remark is sometimes taken as an indication that the first language of Iulius Ausonius (c. AD 290-378) was Gaulish,[26] but may alternatively mean that his first language was Greek. As a physician, he would have cultivated Greek as part of his professional proficiency.

- In the Dialogi de Vita Martini I, 26 by Sulpicius Seuerus (AD 363–425), one of the partners in the dialogue utters the rhetorical commonplace that his deficient Latin might insult the ears of his partners. One of them answers: uel Celtice aut si mauis Gallice loquere dummodo Martinum loquaris ‘speak Celtic or, if you prefer, Gaulish, as long as you speak about Martin’.[27]

- Saint Jerome (writing in AD 386/387) remarked in a commentary on St. Paul's Epistle to the Galatians that the Belgic Treveri spoke almost the same language as the Galatians, rather than Latin.[28] This agrees with an earlier report in AD180 by Lucian.[29]

- In a letter of AD 474 to his brother-in-law, Sidonius Apollinaris, bishop of Clermont in the Auvergne, states that in his younger years, "our nobles... resolved to forsake the barbarous Celtic dialect", evidently in favour of eloquent Latin.[30]

2.3. Medieval Period

- Cassiodorus (ca. 490–585) cites in his book Variae VIII, 12, 7 (dated 526) from a letter to king Athalaric: Romanum denique eloquium non suis regionibus inuenisti et ibi te Tulliana lectio disertum reddidit, ubi quondam Gallica lingua resonauit ‘Finally you found Roman eloquence in regions that were not originally its own; and there the reading of Cicero rendered you eloquent where once the Gaulish language resounded’[31]

- In the 6th century Cyril of Scythopolis (AD 525-559) tells a story about a Galatian monk who was possessed by an evil spirit and was unable to speak, but if forced to, could speak only in Galatian.[32]

- Gregory of Tours wrote in the 6th century (c. 560-575) that a shrine in Auvergne which "is called Vasso Galatae in the Gallic tongue" was destroyed and burnt to the ground.[33] This quote has been held by historical linguistic scholarship to attest that Gaulish was indeed still spoken as late as the mid to late 6th century in France.[34][35]

Conditions of final demise

Despite considerable Romanization of the local material culture, the Gaulish language is held to have survived and coexisted with spoken Latin during the centuries of Roman rule of Gaul.[34] The exact time of the final extinction of Gaulish is unknown, but it is estimated to have been in the late 5th or early 6th century AD,[36] after the collapse of the Western Roman Empire.[37]

The language shift was uneven in its progress and shaped by sociological factors. Although there was a presence of retired veterans in colonies, these did not significantly alter the linguistic composition of Gaul's population, of which 90% was autochthonous;[38][39] instead, the key Latinizing class was the coopted local elite, who sent their children to Roman schools and administered lands for Rome. In the 5th century, at the time of the Western Roman collapse, the vast majority (non-elite and predominantly rural) of the population remained Gaulish speakers, and acquired Latin as their native speech only after the demise of the Empire, as both they and the new Frankish ruling elite adopted the prestige language of their urban literate elite.[37]

Bonnaud[40] maintains that while Latinisation occurred earlier in Provence and in major urban centrers, while Gaulish persisted longest, possibly as late as the tenth century[41] with evidence for continued use according to Bonnaud continuing into the ninth century,[42] in Langres and the surrounding regions, the regions between Clermont, Argenton and Bordeaux, and in Armorica. Fleuriot,[43] Falc'hun,[44] and Gvozdanovic[45] likewise maintained a late survival in Armorica and language contact of some form with the ascendant Breton language; however, it has been noted that there is little uncontroversial evidence supporting a relatively late survival specifically in Brittany whereas there is uncontroversial evidence that supports the relatively late survival of Gaulish in the Swiss Alps and in regions in Central Gaul.[46] Drawing from these data, which include the mapping of substrate vocabulary as evidence, Kerkhof argues that we may "tentatively" posit a survival of Gaulish speaking communities in the "at least into the sixth century" in pockets of mountainous regions of the Central Massif, the Jura, and the Swiss Alps.[46]

3. Corpus

3.1. Summary of Sources

According to the Recueil des inscriptions gauloises, more than 760 Gaulish inscriptions have been found throughout present-day France, with the notable exception of Aquitaine, and in northern Italy.[47] Inscriptions include short dedications, funerary monuments, proprietary statements, and expressions of human sentiments, but the Gauls also left some longer documents of a legal or magical-religious nature,[48] the three longest being the Larzac tablet, the Chamalières tablet and the Lezoux dish. The most famous Gaulish record is the Coligny calendar, a fragmented bronze tablet dating from the 2nd century AD and providing the names of Celtic months over a five-year span; it is a lunisolar calendar attempting to synchronize the solar year and the lunar month by inserting a thirteenth month every two and a half years.

Many inscriptions consist of only a few words (often names) in rote phrases, and many are fragmentary.[49][50] They provide some evidence for morphology and better evidence for personal and mythological names. Occasionally, marked surface clausal configurations provide some evidence of a more formal, or poetic, register. It is clear from the subject matter of the records that the language was in use at all levels of society.

Other sources also contribute to knowledge of Gaulish: Greek and Latin authors mention Gaulish words,[13] personal and tribal names,[51] and toponyms. A short Gaulish-Latin vocabulary (about 20 entries headed De nominib[us] Gallicis) called "Endlicher's Glossary", is preserved in a 9th century manuscript (Öst. Nationalbibliothek, MS 89 fol. 189v).[18]

Some Gaulish loanwords are found in the French language. Today, French contains approximately 150 to 180 words known to be of Gaulish origin, most of which concern pastoral or daily activity.[52][53] If dialectal and derived words are included, the total is approximately 400 words, the largest stock of Celtic words in any Romance language.[54][55]

3.2. Inscriptions

Gaulish inscriptions are edited in the Recueil des Inscriptions Gauloises (R.I.G.), in four volumes:

- Volume 1: Inscriptions in the Greek alphabet, edited by Michel Lejeune (items G-1 –G-281)

- Volume 2.1: Inscriptions in the Etruscan alphabet (Lepontic, items E-1 – E-6), and inscriptions in the Latin alphabet in stone (items l. 1 – l. 16), edited by Michel Lejeune

- Volume 2.2: inscriptions in the Latin alphabet on instruments (ceramic, lead, glass etc.), edited by Pierre-Yves Lambert (items l. 18 – l. 139)

- Volume 3: The Coligny calendar (73 fragments) and that of Villards-d'Héria (8 fragments), edited by Paul-Marie Duval and Georges Pinault

- Volume 4: inscriptions on Celtic coinage, edited by Jean-Baptiste Colbert de Beaulieu and Brigitte Fischer (338 items)

The longest known Gaulish text is the Larzac tablet, found in 1983 in l'Hospitalet-du-Larzac, France. It is inscribed in Roman cursive on both sides of two small sheets of lead. Probably a curse tablet (defixio), it clearly mentions relationships between female names, for example aia duxtir adiegias [...] adiega matir aiias (Aia, daughter of Adiega... Adiega, mother of Aia) and seems to contain incantations regarding one Severa Tertionicna and a group of women (often thought to be a rival group of witches), but the exact meaning of the text remains unclear.[57][58]

The Coligny calendar was found in 1897 in Coligny, France, with a statue identified as Mars. The calendar contains Gaulish words but Roman numerals, permitting translations such as lat evidently meaning days, and mid month. Months of 30 days were marked matus, "lucky", months of 29 days anmatus, "unlucky", based on comparison with Middle Welsh mad and anfad, but the meaning could here also be merely descriptive, "complete" and "incomplete".[59]

The pottery at La Graufesenque[60] is our most important source for Gaulish numerals. Potters shared furnaces and kept tallies inscribed in Latin cursive on ceramic plates, referring to kiln loads numbered 1 to 10:

- 1st cintus, cintuxos (Welsh cynt "before", cyntaf "first", Breton kent "in front" kentañ "first", Cornish kynsa "first", Old Irish céta, Irish céad "first")

- 2nd allos, alos (W ail, Br eil, OIr aile "other", Ir eile)

- 3rd tri[tios] (W trydydd, Br trede, OIr treide)

- 4th petuar[ios] (W pedwerydd, Br pevare)

- 5th pinpetos (W pumed, Br pempet, OIr cóiced)

- 6th suexos (possibly mistaken for suextos, but see Rezé inscription below; W chweched, Br c'hwec'hved, OIr seissed)

- 7th sextametos (W seithfed, Br seizhved, OIr sechtmad)

- 8th oxtumeto[s] (W wythfed, Br eizhved, OIr ochtmad)

- 9th namet[os] (W nawfed, Br naved, OIr nómad)

- 10th decametos, decometos (CIb dekametam, W degfed, Br degvet, OIr dechmad)

The lead inscription from Rezé (dated to the 2nd century, at the mouth of the Loire, 450 kilometres (280 mi) northwest of La Graufesenque) is evidently an account or a calculation and contains quite different ordinals:[61]

- 3rd trilu

- 4th paetrute

- 5th pixte

- 6th suexxe, etc.

Other Gaulish numerals attested in Latin inscriptions include *petrudecametos "fourteenth" (rendered as petrudecameto, with Latinized dative-ablative singular ending) and *triconts "thirty" (rendered as tricontis, with a Latinized ablative plural ending; compare Irish tríocha). A Latinized phrase for a "ten-night festival of (Apollo) Grannus", decamnoctiacis Granni, is mentioned in a Latin inscription from Limoges. A similar formation is to be found in the Coligny calendar, in which mention is made of a trinox[...] Samoni "three-night (festival?) of (the month of) Samonios". As is to be expected, the ancient Gaulish language was more similar to Latin than modern Celtic languages are to modern Romance languages. The ordinal numerals in Latin are prīmus/prior, secundus/alter (the first form when more than two objects are counted, the second form only when two, alius, like alter means "the other", the former used when more than two and the latter when only two), tertius, quārtus, quīntus, sextus, septimus, octāvus, nōnus, and decimus.

A number of short inscriptions are found on spindle whorls and are among the most recent finds in the Gaulish language. Spindle whorls were apparently given to girls by their suitors and bear such inscriptions as:

- moni gnatha gabi / buððutton imon (RIG l. 119) "my girl, take my penis(?)[62]"

- geneta imi / daga uimpi (RIG l. 120) '"I am a young girl, good (and) pretty".

Inscriptions found in Switzerland are rare. The most notable inscription found in Helvetic parts is the Bern zinc tablet, inscribed ΔΟΒΝΟΡΗΔΟ ΓΟΒΑΝΟ ΒΡΕΝΟΔΩΡ ΝΑΝΤΑΡΩΡ (Dobnorēdo gobano brenodōr nantarōr) and apparently dedicated to Gobannus, the Celtic god of metalwork. Furthermore, there is a statue of a seated goddess with a bear, Artio, found in Muri bei Bern, with a Latin inscription DEAE ARTIONI LIVINIA SABILLINA, suggesting a Gaulish Artiū "Bear (goddess)".

Some coins with Gaulish inscriptions in the Greek alphabet have also been found in Switzerland, e.g. RIG IV Nos. 92 (Lingones) and 267 (Leuci). A sword, dating to the La Tène period, was found in Port, near Biel/Bienne, with its blade inscribed with KORICIOC (Korisos), probably the name of the smith.

4. Phonology

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i iː | u uː | |

| Mid | e eː | o oː | |

| Open | a aː |

- vowels:

- short: a, e, i, o u

- long: ā, ē, ī, (ō), ū

- diphthongs: ai, ei, oi, au, eu, ou

| Bilabial | Dental Alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasals | m | n | ||

| Stops | p b | t d | k ɡ | |

| Affricates | ts | |||

| Fricatives | s | (x)1 | ||

| Approximants | j | w | ||

| Liquids | r, l |

- [x] is an allophone of /k/ before /t/.

- occlusives:

- voiceless: p, t, k

- voiced: b, d, g

- resonants

- nasals: m, n

- liquids r, l

- sibilant: s

- affricate: ts

- semi-vowels: w, y

The diphthongs all transformed over the historical period. Ai and oi changed into long ī and eu merged with ou, both becoming long ō. Ei became long ē. In general, long diphthongs became short diphthongs and then long vowels. Long vowels shortened before nasals in coda.

Other transformations include unstressed i became e, ln became ll, a stop + s became ss, and a nasal + velar became /ŋ/ + velar.

The voiceless plosives seem to have been lenis,[clarification needed] unlike in Latin, which distinguished voiced occlusives with a lenis realization from voiceless occlusives with a fortis realization, which caused confusions like Glanum for Clanum, vergobretos for vercobreto, Britannia for Pritannia.[63]

4.1. Orthography

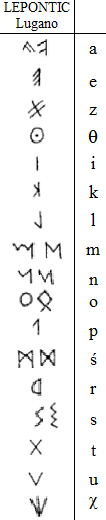

The alphabet of Lugano used in Cisalpine Gaul for Lepontic:

- AEIKLMNOPRSTΘVXZ

The alphabet of Lugano does not distinguish voicing in stops: P represents /b/ or /p/, T is for /d/ or /t/, K for /g/ or /k/. Z is probably for /ts/. U /u/ and V /w/ are distinguished in only one early inscription. Θ is probably for /t/ and X for /g/ (Lejeune 1971, Solinas 1985).

The Eastern Greek alphabet used in southern Gallia Narbonensis:

- αβγδεζηθικλμνξοπρϲτυχω

- ΑΒΓΔΕΖΗΘΙΚΛΜΝΞΟΠΡϹΤΥΧΩ

Χ is used for [x], θ for /ts/, ου for /u/, /ū/, /w/, η and ω for both long and short /e/, /ē/ and /o/, /ō/ while ι is for short /i/ and ει for /ī/. Note that the sigma, in the Eastern Greek alphabet, is a Ϲ (lunate sigma). All Greek letters were used except phi and psi.

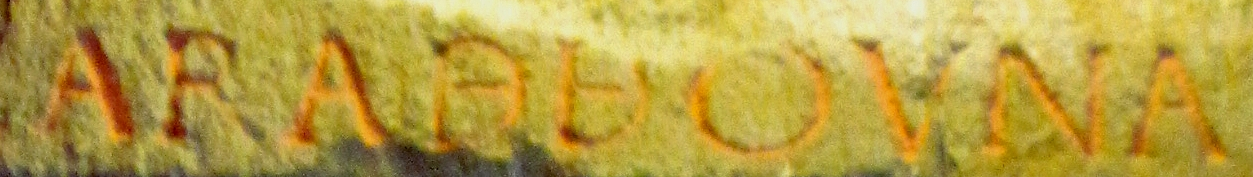

Latin alphabet (monumental and cursive) in use in Roman Gaul:

- ABCDÐEFGHIKLMNOPQRSTVXZ

- abcdðefghiklmnopqrstvxz

G and K are sometimes used interchangeably (especially after R). Ð/ð, ds and s may represent /ts/ and/or /dz/. X, x is for [x] or /ks/. Q is only used rarely (Sequanni, Equos) and may represent an archaism (a retained *kw) or, as in Latin, an alternate spelling of -cu- (for original /kuu/, /kou/, or /kom-u/).[66] Ð and ð are used to represent the letter ![]() (tau gallicum, the Gaulish dental affricate). In March, 2020 Unicode added four characters to represent tau gallicum:[67]

(tau gallicum, the Gaulish dental affricate). In March, 2020 Unicode added four characters to represent tau gallicum:[67]

- U+A7C7 Ꟈ LATIN CAPITAL LETTER D WITH SHORT STROKE OVERLAY

- U+A7C8 ꟈ LATIN SMALL LETTER D WITH SHORT STROKE OVERLAY

- U+A7C9 Ꟊ LATIN CAPITAL LETTER S WITH SHORT STROKE OVERLAY

- U+A7CA ꟊ LATIN SMALL LETTER S WITH SHORT STROKE OVERLAY

4.2. Sound Laws

- Gaulish changed the PIE voiceless labiovelar kʷ to p, a development also observed in the Brittonic languages (as well as Greek and some Italic languages like the Osco-Umbrian languages), while other Celtic languages retained the labiovelar. Thus, the Gaulish word for "son" was mapos,[68] contrasting with Primitive Irish *maq(q)os (attested genitive case maq(q)i), which became mac (gen. mic) in modern Irish. In modern Welsh the word map, mab (or its contracted form ap, ab) is found in surnames. Similarly one Gaulish word for "horse" was epos (in Old Breton eb and modern Breton keneb "pregnant mare") while Old Irish has ech, the modern Irish language and Scottish Gaelic each, and Manx egh, all derived from proto-Indo-European *h₁eḱwos.[69] The retention or innovation of this sound does not necessarily signify a close genetic relationship between the languages; Goidelic and Brittonic are, for example, both Insular Celtic languages and quite closely related.

- The Proto-Celtic voiced labiovelar *gʷ (From PIE *gʷʰ) became w: *gʷediūmi → uediiumi "I pray" (but Celtiberian Ku.e.z.o.n.to /gueðonto/ < *gʷʰedʰ-y-ont 'imploring, pleading', Old Irish guidim, Welsh gweddi "to pray").

- PIE ds, dz became /tˢ/, spelled ð: *neds-samo → neððamon (cf. Irish nesamh "nearest", Welsh nesaf "next"). Modern Breton nes and nesañ "next".

- PIE ew became eu or ou, and later ō: PIE *tewtéh₂ → teutā/toutā → tōtā "tribe" (cf. Irish túath, Welsh tud "people").

- PIE ey became ei, ē and ī PIE *treyes → treis → trī (cf. Irish trí "three").

- Additionally, intervocalic /st/ became the affricate [tˢ] (alveolar stop + voiceless alveolar stop) and intervocalic /sr/ became [ðr] and /str/ became [θr]. Finally, when a labial or velar stop came before /t/ or /s/, the two sounds merged into the fricative [χ].

5. Morphology

There was some areal (or genetic, see Italo-Celtic) similarity to Latin grammar, and the French historian Ferdinand Lot argued that it helped the rapid adoption of Vulgar Latin in Roman Gaul.[70]

5.1. Noun Cases

Gaulish had seven cases: the nominative, vocative, accusative, genitive, dative, instrumental and the locative case. Greater epigraphical evidence attests common cases (nominative and accusative) and common stems (-o- and -a- stems) than for cases less frequently used in inscriptions or rarer -i-, -n- and -r- stems. The following table summarises the reconstructed endings for the words *toṷtā "tribe, people", *mapos "boy, son", *ṷātis "seer", *gutus "voice", *brātīr "brother".[71][72]

| Case | Singular | Plural | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ā-stem | o-stem | i-stem | u-stem | r-stem | ā-stem | o-stem | i-stem | u-stem | r-stem | ||

| Nominative | *toṷtā | *mapos (n. *-on) | *ṷātis | *gutus | *brātīr | *toṷtās | *mapoi | *ṷātīs | *gutoṷes | *brāteres | |

| Vocative | *toṷtā | *mape | *ṷāti | *gutu | *brāter | *toṷtās | *mapoi | *ṷātīs | *gutoṷes | *brāteres | |

| Accusative | *toṷtan ~ *toṷtam > *toṷtim | *mapon ~ *mapom (n. *-on) | *ṷātin ~ *ṷātim | *gutun ~ *gutum | *brāterem | *toṷtās | *mapōs > *mapūs | *ṷātīs | *gutūs | *brāterās | |

| Genitive | toṷtās > *toṷtiās | *mapoiso > *mapi | *ṷātēis | *gutoṷs > *gutōs | *brātros | *toṷtanom | *mapon | *ṷātiom | *gutoṷom | *brātron | |

| Dative | *toṷtai > *toṷtī | *mapūi > *mapū | *ṷātei > *ṷāte | *gutoṷei > gutoṷ | *brātrei | *toṷtābo(s) | *mapobo(s) | *ṷātibo(s) | *gutuibo(s) | *brātrebo(s) | |

| Instrumental | *toṷtia > *toṷtī | *mapū | *ṷātī | *gutū | *brātri | *toṷtābi(s) | *mapuis > *mapūs | *ṷātibi(s) | *gutuibi(s) | *brātrebi(s) | |

| Locative | *toṷtī | *mapei > *mapē | *ṷātei | *gutoṷ | *brātri | *toṷtābo(s) | *mapois | *ṷātibo(s) | *gutubo(s) | *brātrebo(s) | |

In some cases, a historical evolution is attested; for example, the dative singular of a-stems is -āi in the oldest inscriptions, becoming first *-ăi and finally -ī as in Irish a-stem nouns with attenuated (slender) consonants: nom. lámh "hand, arm" (cf. Gaul. lāmā) and dat. láimh (< *lāmi; cf. Gaul. lāmāi > *lāmăi > lāmī). Further, the plural instrumental had begun to encroach on the dative plural (dative atrebo and matrebo vs. instrumental gobedbi and suiorebe), and in the modern Insular languages, the instrumental form is known to have completely replaced the dative.

For o-stems, Gaulish also innovated the pronominal ending for the nominative plural -oi and genitive singular -ī in place of expected -ōs and -os still present in Celtiberian (-oś, -o). In a-stems, the inherited genitive singular -as is attested but was subsequently replaced by -ias as in Insular Celtic. The expected genitive plural -a-om appears innovated as -anom (vs. Celtiberian -aum).

There also appears to be a dialectal equivalence between -n and -m endings in accusative singular endings particularly, with Transalpine Gaulish favouring -n, and Cisalpine favouring -m. In genitive plurals the difference between -n and -m relies on the length of the preceding vowel, with longer vowels taking -m over -n (in the case of -anom this is a result of its innovation from -a-om).

5.2. Verbs

Gaulish verbs have present, future, perfect, and imperfect tenses; indicative, subjunctive, optative and imperative moods; and active and passive voices.[72][73] Verbs show a number of innovations as well. The Indo-European s-aorist evolved into the Gaulish t-preterit, formed by merging an old 3rd personal singular imperfect ending -t- to a 3rd personal singular perfect ending -u or -e and subsequent affixation to all forms of the t-preterit tense. Similarly, the s-preterit is formed from the extension of -ss (originally from the third person singular) and the affixation of -it to the third person singular (to distinguish it as such). Third-person plurals are also marked by the addition of -s in the preterit system.

6. Syntax

6.1. Word Order

Most Gaulish sentences seem to consist of a subject–verb–object word order:

-

-

Subject Verb Indirect Object Direct Object martialis dannotali ieuru ucuete sosin celicnon Martialis, son of Dannotalos, dedicated this edifice to Ucuetis

-

Some, however, have patterns such as verb–subject–object (as in living Insular Celtic languages) or with the verb last. The latter can be seen as a survival from an earlier stage in the language, very much like the more archaic Celtiberian language.

Sentences with the verb first can be interpreted, however, as indicating a special purpose, such as an imperative, emphasis, contrast, and so on. Also, the verb may contain or be next to an enclitic pronoun or with "and" or "but", etc. According to J. F. Eska, Gaulish was certainly not a verb-second language, as the following shows:

-

-

ratin briuatiom frontu tarbetisonios ie(i)uru NP.Acc.Sg. NP.Nom.Sg. V.3rd Sg. Frontus Tarbetisonios dedicated the board of the bridge.

-

Whenever there is a pronoun object element, it is next to the verb, as per Vendryes' Restriction. The general Celtic grammar shows Wackernagel's Rule, so putting the verb at the beginning of the clause or sentence. As in Old Irish[74] and traditional literary Welsh,[75] the verb can be preceded by a particle with no real meaning by itself but originally used to make the utterance easier.

-

-

sioxt-i albanos panna(s) extra tuð(on) CCC V-Pro.Neut. NP.Nom.Sg. NP.Fem.Acc.Pl. PP Num. Albanos added them, vessels beyond the allotment (in the amount of) 300.

-

-

-

to-me-declai obalda natina Conn.-Pro.1st.Sg.Acc.-V.3rd.Sg. NP.Nom.Sg. Appositive Obalda, (their) dear daughter, set me up.

-

According to Eska's model, Vendryes' Restriction is believed to have played a large role in the development of Insular Celtic verb-subject-object word order. Other authorities such as John T. Koch, dispute that interpretation.

Considering that Gaulish is not a verb-final language, it is not surprising to find other "head-initial" features:

- Genitives follow their head nouns:

-

-

atom deuogdonion The border of gods and men.

-

- The unmarked position for adjectives is after their head nouns:

-

-

toutious namausatis citizen of Nîmes

-

- Prepositional phrases have the preposition, naturally, first:

-

-

in alixie in Alesia

-

- Passive clauses:

-

-

uatiounui so nemetos commu escengilu To Vatiounos this shrine (was dedicated) by Commos Escengilos

-

6.2. Subordination

Subordinate clauses follow the main clause and have an uninflected element (jo) to show the subordinate clause. This is attached to the first verb of the subordinate clause.

-

-

gobedbi dugijonti-jo ucuetin in alisija NP.Dat/Inst.Pl. V.3rd.Pl.- Pcl. NP.Acc.Sg. PP to the smiths who serve Ucuetis in Alisia

-

Jo is also used in relative clauses and to construct the equivalent of THAT-clauses

-

-

scrisu-mi-jo uelor V.1st.Sg.-Pro.1st Sg.-Pcl. V.1st Sg. I wish that I spit

-

This element is found residually in the Insular Celtic languages and appears as an independent inflected relative pronoun in Celtiberian, thus:

- Welsh

- modern sydd "which is" ← Middle Welsh yssyd ← *esti-jo

- vs. Welsh ys "is" ← *esti

- Irish

- Old Irish relative cartae "they love" ← *caront-jo

- Celtiberian

- masc. nom. sing. ioś, masc. dat. sing. iomui, fem. acc. plural iaś

6.3. Clitics

Gaulish had object pronouns that infixed inside a word:

-

-

to- so -ko -te Conn.- Pro.3rd Sg.Acc - PerfVZ - V.3rd Sg he gave it

-

Disjunctive pronouns also occur as clitics: mi, tu, id. They act like the emphasizing particles known as notae augentes in the Insular Celtic languages.

-

-

dessu- mii -iis V.1st.Sg. Emph.-Pcl.1st Sg.Nom. Pro.3rd Pl.Acc. I prepare them

-

-

-

buet- id V.3rd Sg.Pres.Subjunc.- Emph.Pcl.3rd Sg.Nom.Neut. it should be

-

Clitic doubling is also found (along with left dislocation), when a noun antecedent referring to an inanimate object is nonetheless grammatically animate. (There is a similar construction in Old Irish.)

7. Modern Usage

In an interview, Swiss folk metal band Eluveitie said that some of their songs are written in a reconstructed form of Gaulish. The band asks scientists for help in writing songs in the language.[76] The name of the band comes from graffiti on a vessel from Mantua (c. 300 BC).[77] The inscription in Etruscan letters reads eluveitie, which has been interpreted as the Etruscan form of the Celtic (h)elvetios ("the Helvetian"),[78] presumably referring to a man of Helvetian descent living in Mantua.

References

- Forster & Toth 2003.

- Stifter 2012, p. 107

- Eska 2012, p. 534.

- Stifter 2012, p. 27

- Eska 2008, p. 165.

- Cited after (Stifter 2012)

- Vath & Ziegler 2017, p. 1174.

- de Hoz, Javier (2005). "Ptolemy and the linguistic history of the Narbonensis". in de Hoz, Javier. New approaches to Celtic place-names in Ptolemy’s Geography. Ediciones Clásicas. ISBN 978-8478825721.

- Corinthiorum amator iste uerborum, iste iste rhetor, namque quatenus totus Thucydides, tyrannus Atticae febris: tau Gallicum, min et sphin ut male illisit, ita omnia ista uerba miscuit fratri. — Virgil, Catalepton II: "THAT lover of Corinthian words or obsolete, That--well, that spouter, for that all of Thucydides, a tyrant of Attic fever: that he wrongly fixed on the Gallic tau and min and spin, thus he mixed all those words for [his] brother".

- "The Internet Classics Archive - The Gallic Wars by Julius Caesar". mit.edu. http://classics.mit.edu/Caesar/gallic.1.1.html.

- BG I 29,1 In castris Helvetiorum tabulae repertae sunt litteris Graecis confectae et ad Caesarem relatae, quibus in tabulis nominatim ratio confecta erat, qui numerus domo exisset eorum qui arma ferre possent, et item separatim, quot pueri, senes mulieresque. "In the camp of the Helvetii, lists were found, drawn up in Greek characters, and were brought to Caesar, in which an estimate had been drawn up, name by name, of the number who had gone forth from their country who were able to bear arms; and likewise the numbers of boys, old men, and women, separately."

- BG VI 6,14 Magnum ibi numerum versuum ediscere dicuntur. Itaque annos nonnulli vicenos in disciplina permanent. Neque fas esse existimant ea litteris mandare, cum in reliquis fere rebus, publicis privatisque rationibus Graecis litteris utantur. Id mihi duabus de causis instituisse videntur, quod neque in vulgum disciplinam efferri velint neque eos, qui discunt, litteris confisos minus memoriae studere: quod fere plerisque accidit, ut praesidio litterarum diligentiam in perdiscendo ac memoriam remittant. "They are said there to learn by heart a great number of verses; accordingly some remain in the course of training twenty years. Nor do they regard it divinely lawful to commit these to writing, though in almost all other matters, in their public and private transactions, they use Greek letters. That practice they seem to me to have adopted for two reasons: because they neither desire their doctrines to be divulged among the mass of the people, nor those who learn, to devote themselves the less to the efforts of memory, relying on writing; since it generally occurs to most men, that, in their dependence on writing, they relax their diligence in learning thoroughly, and their employment of the memory."

- Pierre-Yves Lambert, La langue gauloise, éditions errance 1994.

- Bruno Rochette, "Language Policies in the Roman Republic and Empire," translated by James Clackson, in A Companion to the Latin Language (Blackwell, 2011), p. 550; Stefan Zimmer, "Indo-European," in Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia (ABC-Clio, 2006), p. 961; Leonard A. Curchin, "Literacy in the Roman Provinces: Qualitative and Quantitative Data from Central Spain," American Journal of Philology 116.3 (1995), p. 464; Richard Miles, "Communicating Culture, Identity, and Power," in Experiencing Rome: Culture, Identity and Power in the Roman Empire (Routledge, 2000), pp. 58–59.

- Alex Mullen, Southern Gaul and the Mediterranean: Multilingualism and Multiple Identities in the Iron Age and Roman Periods (Cambridge University Press, 2013), p. 269 (note 19) and p. 300 on trilingualism.

- On the Detection and Overthrow of the So-Called Gnosis; Adv. haer., book I, praef. 3 "You will not expect from me, as a resident among the Keltae, and accustomed for the most part to use a barbarous dialect, any display of rhetoric"

- R. Thurneysen, "Irisches und Gallisches," in: Zeitschrift für Celtische Philologie 14 (1923) 1-17.

- "Archived copy". http://www.univie.ac.at/indogermanistik/bilder/quellentexte/endlicher.jpg.

- Aulus Gellius, Noctes Atticae, Extract: ueluti Romae nobis praesentibus uetus celebratusque homo in causis, sed repentina et quasi tumultuaria doctrina praeditus, cum apud praefectum urbi uerba faceret et dicere uellet inopi quendam miseroque uictu uiuere et furfureum panem esitare uinumque eructum et feditum potare. "hic", inquit,"eques Romanus apludam edit et flocces bibit". aspexerunt omnes qui aderant alius alium, primo tristiores turbato et requirente uoltu quidnam illud utriusque uerbi foret: post deinde, quasi nescio quid Tusce aut Gallice dixisset, uniuersi riserunt. "For instance in Rome in our presence, a man experienced and celebrated as a pleader, but furnished with a sudden and, as it were, hasty education, was speaking to the Prefect of the City, and wished to say that a certain man with a poor and wretched way of life ate bread from bran and drank bad and spoiled wine. 'This Roman knight', he said, 'eats apluda and drinks flocces.' All who were present looked at each other, first seriously and with an inquiring expression, wondering what the two words meant; thereupon, as if he might have said something in, I don’t know, Gaulish or Etruscan, all of them burst out laughing."(based on BLOM 2007: 183)

- Cassius Dio Roman History XIII, cited in Zonaras 8, 21 "Spain, in which the Saguntines dwell, and all the adjoining land is in the western part of Europe. It extends for a great distance along the inner sea, past the Pillars of Hercules, and along the Ocean itself; furthermore, it includes the regions inland for a very great distance, even to the Pyrenees. This range, beginning at the sea called anciently the sea of the Bebryces, but later the sea of the Narbonenses, reaches to the great outer sea, and contains many diverse nationalities; it also separates the whole of Spain from the neighbouring land of Gaul. The tribes were neither of one speech, nor did they have a common government. As a result, they were not known by one name: the Romans called them Spaniards, but the Greeks Iberians, from the river Iberus [Ebro]."

- Cassius Dio Roman History XII,20 "The Insubres, a Gallic tribe, after securing allies from among their kinsmen beyond the Alps, turned their arms against the Romans"

- Cassius Dio Roman History XIV, cited in Zonoras 8 "Hannibal, desiring to invade Italy with all possible speed, marched on hurriedly, and traversed without a conflict the whole of Gaul lying between the Pyrenees and the Rhone. Then Hannibal, in haste to set out for Italy, but suspicious of the more direct roads, turned aside from them and followed another, on which he met with grievous hardships. For the mountains there are exceedingly precipitous, and the snow, which had fallen in great quantities, was driven by the winds and filled the chasms, and the ice was frozen very hard. ... For this reason, then, he did not turn back, but suddenly appearing from the Alps, spread astonishment and fear among the Romans. Hannibal ... proceeded to the Po, and when he found there neither rafts nor boats — for they had been burned by Scipio — he ordered his brother Mago to swim across with the cavalry and pursue the Romans, whereas he himself marched up toward the sources of the river, and then ordered that the elephants should cross down stream. In this manner, while the water was temporarily dammed and spread out by the animals' bulk, he effected a crossing more easily below them. [...] Of the captives taken he killed the Romans, but released the rest. This he did also in the case of all those taken alive, hoping to conciliate the cities by their influence. And, indeed, many of the other Gauls as well as Ligurians and Etruscans either murdered the Romans dwelling within their borders, or surrendered them and then transferred their allegiance."

- Cassius Dio Roman History XLVI,55,4-5 "Individually, however, in order that they should not be thought to be appropriating the entire government, they arranged that both Africas, Sardinia, and Sicily should be given to Caesar to rule, all of Spain and Gallia Narbonensis to Lepidus, and the rest of Gaul, both south and north of the Alps, to Antony. The former was called Gallia Togata, as I have stated, [evidently in a lost portion of Cassius Dio's work] because it seemed to be more peaceful than the other divisions of Gaul, and because the inhabitants already employed the Roman citizen-garb; the other was termed Gallia Comata because the Gauls there for the most part let their hair grow long, and were in this way distinguished from the others."

- Fideicommissa quocumque sermone relinqui possunt, non solum Latina uel Graeca, sed etiam Punica uel Gallicana uel alterius cuiuscumque genti Fideicommissa may be left in any language, not only in Latin or Greek, but also in Punic or Gallicanian or of whatever other people. David Stifter, ‘Old Celtic Languages’, 2012, p110

- Ausonius, Epicedion in patrem 9–10 (a first-person poem written in the voice of his father), "Latin did not flow easily, but the language of Athens provided me with sufficient words of polished eloquence" (sermone inpromptus Latio, verum Attica lingua suffecit culti vocibus eloquii); J.N. Adams, Bilingualism and the Latin Language (Cambridge University Press, 2003), pp. 356–357, especially note 109, citing R.P.H. Green, The Works of Ausonius (Oxford: Clarendon Press, p. 1991), p. 276 on the view that Gaulish was the native language of Iulius Ausonius.

- Bordeaux [Burdigala] was a Gaulish enclave in Aquitania according to Strabo's Geographia IV, 2,1

- David Stifter, ‘Old Celtic Languages’, 2012, p110

- Jerome (Latin: Hieronymus), writing in AD 386-7, Commentarii in Epistulam ad Galatas II, 3 =Patrologia Latina 26, 357, cited after David Stifter, Old Celtic Languages, 2012, p.110. Galatas excepto sermone Graeco, quo omnis oriens loquitur, propriam linguam eandem paene habere quam Treuiros "Apart from the Greek language, which is spoken throughout the entire East, the Galatians have their own language, almost the same as the Treveri".

- Lucian, Pamphlet against the pseudo-prophet Alexandros, cited after Eugenio Luján, The Galatian Place Names in Ptolemy, in: Javier de Hoz, Eugenio R. Luján, Patrick Sims-Williams (eds.), New Approaches to Celtic Place-Names in Ptolemy's Geography, Madrid: Ediciones Clásicas 2005, 263. Lucian, an eye-witness, reports on Alexandros (around AD 180) using interpreters in Paphlagonia (northeast of Galatia): ἀλλὰ καὶ βαρβάροις πολλάκις ἔρχησεν, εἴ τις τῇ πατρίῳ ἔροιτο φωνῇ, Συριστὶ ἢ Κελτιστὶ, ῥᾳδίως ἐξευρίσκων τινὰς ἐπιδημοῦντας ὁμοεθνεῖς τοῖς δεδωκόσιν. "But he [Alexandros] gave oracles to barbarians many times, given that if someone asked a question in his [the questioner's] native language, in Syrian or in Celtic, he [Alexandros] easily found residents of the same people as the questioners"

- Sidonius Apollinaris (Letters, III.3.2) mitto istic ob gratiam pueritiae tuae undique gentium confluxisse studia litterarum tuaeque personae quondam debitum, quod sermonis Celtici squamam depositura nobilitas nunc oratorio stilo, nunc etiam Camenalibus modis imbuebatur. I will forget that your schooldays brought us a veritable confluence of learners and the learned from all quarters, and that if our nobles were imbued with the love of eloquence and poetry, if they resolved to forsake the barbarous Celtic dialect, it was to your personality that they owed all. Alternative translation according to David Stifter: ...sermonis Celtici squamam depositura nobilitas nunc oratorio stilo, nunc etiam Camenalibus modis imbuebatur ‘...the (Arvernian) nobility, wishing to cast off the scales of Celtic speech, will now be imbued (by him = brother-in-law Ecdicius) with oratorial style, even with tunes of the Muses’.

- after BLOM 2007:188, cited from David Stifter, ‘Old Celtic Languages’, 2012, p110

- εἰ δὲ πάνυ ἐβιάζετο, Γαλατιστὶ ἐφθέγγετο. ‘If he was forced to, he spoke in Galatian’ (Vita S. Euthymii 55; after Eugenio Luján, ‘The Galatian Place Names in Ptolemy’, in: Javier de Hoz, Eugenio R. Luján, Patrick Sims-Williams (eds.), New Approaches to Celtic Place-Names in Ptolemy's Geography, Madrid: Ediciones Clásicas 2005, 264).

- Hist. Franc., book I, 32 Veniens vero Arvernos, delubrum illud, quod Gallica lingua Vasso Galatæ vocant, incendit, diruit, atque subvertit. And coming to Clermont [to the Arverni] he set on fire, overthrew and destroyed that shrine which they call Vasso Galatæ in the Gallic tongue.

- Laurence Hélix (2011). Histoire de la langue française. Ellipses Edition Marketing S.A.. p. 7. ISBN 978-2-7298-6470-5. "Le déclin du Gaulois et sa disparition ne s'expliquent pas seulement par des pratiques culturelles spécifiques: Lorsque les Romains conduits par César envahirent la Gaule, au 1er siecle avant J.-C., celle-ci romanisa de manière progressive et profonde. Pendant près de 500 ans, la fameuse période gallo-romaine, le gaulois et le latin parlé coexistèrent; au VIe siècle encore; le temoignage de Grégoire de Tours atteste la survivance de la langue gauloise."

- Blom, Alderik. "Lingua gallica, lingua celtica: Gaulish, Gallo-Latin, or Gallo-Romance?." Keltische Forschungen 4 (2009). https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:eec44e1b-2292-4d96-a273-2f99a60b19f3/download_file?file_format=pdf&safe_filename=KF%2B4%2B-%2BBlom%2B7-54.pdf&type_of_work=Journal+article

- Stifter 2012, p. 109.

- Mufwene, Salikoko S. "Language birth and death." Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 33 (2004): 201-222. Page 213: "... the Romans did not colonize Europe on the settlement model... However, the local rulers, who had Romanized already, maintained Latin as the language of their administrations... (footnote) Latin was spread outside Rome largely by foreign mercenaries in Roman legions, similar to how English is spreading today as a world lingua franca significantly by nonnative speakers using it and teaching it to others.. (main) More significant is that the Roman colonies were not fully Latinized in the fifth century. When the Romans left, lower classes (the population majority) continued to use Celtic languages, especially in rural areas..." Page 214: "The protracted development of the Romance languages under the substrate influence of Celtic languages is correlated with the gradual loss of the latter, as fewer and fewer children found it useful to acquire the Celtic languages and instead acquired [regional Latin]... Today the Celtic languages and other more indigenous languages similar to Basque, formerly spoken in the same territory, have vanished." Page 215: "[In contrast to the Angles and Saxons who kept Germanic speech and religion], the Franks surrendered their Germanic traditions, embracing the language and religion of the indigenous rulers, Latin and Catholicism."

- Lodge, R. Anthony (1993). French: From Dialect to Standard. pp. 46. ISBN 9780415080712. https://books.google.com/books?id=hfanhTGi-z0C.

- Craven, Thomas D. (2002). Comparative Historical Dialectology: Italo-Romance Clues to Ibero-Romance Sound Change. John Benjamins Publishing. pp. 51. ISBN 1588113132. https://books.google.com/books?id=XvODm8_Y6CgC&q=Braudel&pg=PA1.

- P Bonnaud (1981). Terres et langages. Peuples et régions. Clermont-Ferrand: Auvernha Tara d'Oc. pp. 109–110.

- Lodge, R. Anthony (1993). French: From Dialect to Standard. p. 43. ISBN 9780415080712. https://books.google.com/books?id=hfanhTGi-z0C.

- P Bonnaud (1981). Terres et langages. Peuples et régions. Clermont-Ferrand: Auvernha Tara d'Oc. pp. 38.

- Léon Fleuriot. Les origins de la Bretagne. Paris: Bibliothèque historique Payot, Éditions Payot. p. 77.

- François Falc'hun. "Celtique continental et celtique insulaire en Breton". Annales de Bretagne 70 (4): 431–432.

- Jadranka Gvozdanovic (2009). Celtic and Slavic and the Great Migrations. Heidelberg: Winter Verlag.

- Kerkhof, Peter Alexander (2018). "Language, law and loanwords in early medieval Gaul: language contact and studies in Gallo-Romance phonology". Page 50

- Peter Schrijver, "Gaulish", in Encyclopedia of the Languages of Europe, ed. Glanville Price (Oxford: Blackwell, 1998), 192.

- null

- Schmidt, Karl Horst, "The Celtic Languages of Continental Europe" in: Bulletin of the Board of Celtic Studies volume XXVIII. 1980. University of Wales Press.

- Article by Lambert, Pierre-Yves, Bulletin of the Board of Celtic Studies volume XXXIV. 1987. University of Wales Press.

- C. Iulius Caesar, "Commentarii de Bello Gallico"

- Pierre-Yves Lambert, La langue gauloise, éditions errance 1994. p. 185.

- M. H. Offord, French words: past, present, and future, pp. 36-37 https://books.google.com/books?id=FXystBj82S8C&pg=PA36&lpg=PA36#v=onepage&q&f=false

- W. Meyer-Lübke, Romanisches etymologisches Wörterbuch, Heidelberg, 3rd edition 1935.

- Lambert 185

- Koch 2005, p. 1106

- Lejeune, Michel; Fleuriot, L.; Lambert, P. Y.; Marichal, R.; Vernhet, A. (1985), Le plomb magique du Larzac et les sorcières gauloises, CNRS, ISBN 2-222-03667-4

- Inscriptions and French translations on the lead tablets from Larzac http://www.arbre-celtique.com/encyclopedie/plomb-du-larzac-233.htm

- Bernhard Maier: Lexikon der keltischen Religion und Kultur. S. 81 f.

- "la graufesenque". ac-toulouse.fr. http://pedagogie.ac-toulouse.fr/culture/divers/lagraufesenque.htm.

- Pierre-Yves Lambert, David Stifter ‘Le texte gaulois de Rezé’, Études Celtiques 38:139-164 (2012)

- Delamarre 2008, p. 92-93

- Paul Russell, An Introduction to the Celtic Languages, (London: Longman, 1995), 206-7.

- Delamarre, Xavier. Dictionnaire de la langue gauloise. Editions Errance, Paris, 2008, p. 299

- Greg Woolf (2007). Ancient civilizations: the illustrated guide to belief, mythology, and art. Barnes & Noble. p. 415. ISBN 978-1-4351-0121-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=94NuSg3tlsgC&q=Gaulish+Greek.

- Stifter, David. (Recension of) Helmut Birkhan, Kelten. Celts. Bilder ihrer Kultur. Images of their Culture, Wien 1999, in: Die Sprache, 43/2, 2002-2003, pp. 237-243

- Everson, Michael; Lilley, Chris (2019-05-26). "L2/19-179: Proposal for the addition of four Latin characters for Gaulish". https://www.unicode.org/L2/L2019/19179-n5044-tau-gallicum.pdf.

- Delamarre 2008, p. 215-216

- Delamarre 2008, p. 163

- La Gaule (1947); for the relevance of the question of the transition from Gaulish to Latin in French national identity, see also Nos ancêtres les Gaulois.

- Lambert 2003 pp.51–67

- Václav, Blažek. "Gaulish language". https://digilib.phil.muni.cz/handle/11222.digilib/114125.

- David, Stifter (2008). "Old Celtic Languages: Gaulish. General Information" (in en). http://eprints.maynoothuniversity.ie/3740/.

- Thurneysen, Rudolf (1993). A Grammar of Old Irish. School of Celtic Studies, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies. ISBN 978-1-85500-161-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=CTSANgAACAAJ.

- Williams, Stephen J., Elfennau Gramadeg Cymraeg. Gwasg Prifysgol Cymru, Caerdydd. 1959.

- "Interview With Eluveiti". Headbangers India. http://www.headbangers.in/interviews/interview-eluveitie/.

- Reproduction in Raffaele Carlo De Marinis, Gli Etruschi a nord del Po, Mantova, 1986.

- Stifter, David. "MN·2 – Lexicon Leponticum". University of Vienna. http://www.univie.ac.at/lexlep/wiki/MN·2.