Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bac Viet Le | -- | 1991 | 2022-11-30 00:43:04 | | | |

| 2 | Vivi Li | Meta information modification | 1991 | 2022-12-01 02:07:11 | | | | |

| 3 | Vivi Li | + 3 word(s) | 1994 | 2022-12-05 05:10:43 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Le, B.V.; Podszywałow-Bartnicka, P.; Piwocka, K.; Skorski, T. PARP Inhibitor-Induced Synthetic Lethality. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/37176 (accessed on 15 January 2026).

Le BV, Podszywałow-Bartnicka P, Piwocka K, Skorski T. PARP Inhibitor-Induced Synthetic Lethality. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/37176. Accessed January 15, 2026.

Le, Bac Viet, Paulina Podszywałow-Bartnicka, Katarzyna Piwocka, Tomasz Skorski. "PARP Inhibitor-Induced Synthetic Lethality" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/37176 (accessed January 15, 2026).

Le, B.V., Podszywałow-Bartnicka, P., Piwocka, K., & Skorski, T. (2022, November 30). PARP Inhibitor-Induced Synthetic Lethality. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/37176

Le, Bac Viet, et al. "PARP Inhibitor-Induced Synthetic Lethality." Encyclopedia. Web. 30 November, 2022.

Copy Citation

The advanced development of synthetic lethality has opened the doors for specific anti-cancer medications of personalized medicine and efficient therapies against cancers. One of the most popular approaches being investigated is targeting DNA repair pathways as the implementation of the poly-ADP ribose polymerase 1 (PARP) inhibitor (PARPi) into individual or combinational therapeutic schemes. Such treatment has been effectively employed against homologous recombination-defective solid tumors as well as hematopoietic malignancies. In the most common aspect of precision medicine, PARPi triggers synthetic lethality in cancer cells harboring BRCA1/2 mutations/deficiencies.

bone marrow microenvironment

DNA repair

PARP inhibitors

PARPi resistance

leukemia cells

synthetic lethality

1. Introduction

Synthetic lethality is a biological process inducing cell death, which is based on the simultaneous inhibition of two pathways that act parallelly in a process required for cell survival. Meanwhile, the inhibition of only one pathway results in cell survival. The synthetic lethality strategy has been widely implemented in anti-cancer therapies. As one pathway may be inactivated in cancer cells due to transformation-related changes, targeting the other pathway triggers cell death while sparing healthy cells [1].

One of the critical features of cancer cells is genomic instability generated by the accumulation of DNA damage, including DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs), which are one of the most lethal DNA lesions in cells [2][3]. However, cancer cells are able to survive and proliferate by modulating their DNA repair pathways, which may differ from those in normal cells [4].

DSBs can be repaired by two major mechanisms: BRCA1/2-mediated homologous recombination (HR) and canonical DNA-PKcs-mediated non-homologous end joining (c-NHEJ) [5]. HR is the major DSB repair mechanism in the S cell cycle phase, whereas c-NHEJ repairs DSBs throughout the cell cycle [6][7]. When HR is inactivated due to deficiencies in BRCA1/2, the prevention and repair of DSBs highly depend on poly-ADP ribose polymerase 1 (PARP1)-mediated base excision repair (BER) and alternative-non-homologous end-joining (a-NHEJ) [8][9]. a-NHEJ is also called microhomology-mediated end-joining (MMEJ) [10], and a-NHEJ/MMEJ involving DNA polymerase theta (Polθ) is called Polθ-mediated end-joining (TMEJ) [11]. Therefore, the inhibition of PARP1 can lead to the induction of the synthetic lethality in proliferating cells harboring HR deficiency (HRD) due to mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2—for example, [12][13][14][15][16]. Those studies led to the development and implementation of the synthetic lethality triggered by the PARP inhibitor (PARPi), which is currently one of the most effective agents against HR-deficient malignancies [17]. Concomitant c-NHEJ deficiencies enhance PARPi-mediated synthetic lethality in HR-deficient cells [18].

FDA-approved PARPi has been administered to patients with BRCA1/2-mutated cancers such as breast and ovarian carcinomas [19][20][21][22]. Although leukemia has not been recognized as a typical BRCA1/2-mutated cancer, researchers' group and others have recently reported that certain types of leukemias and other hematopoietic malignancies display HR with/without concomitant c-NHEJ functional deficiency caused by leukemia-inducing mutations [18][23][24][25][26]. In addition, HR and/or c-NHEJ deficiency could be induced by the treatment of leukemia/solid tumors with the tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKi) against the cancer-driven oncogenic tyrosine kinases (e.g., FLT3(ITD), JAK2(V617F), c-KIT(N822K), IGF-1R, EGFR). Therefore, oncogenic tyrosine kinase (OTK)-driven malignancies can effectively respond to PARPi after the inhibition of OTK [27][28][29][30][31].

2. PARPi-Induced Synthetic Lethality in BRCA1/2-Mutated Cancers

The usage of PARPi, which predominantly blocks the activity of PARP1, PARP2 and PARP3, is a well-established example of synthetic lethality-based therapy in BRCA1/2-mutated cancers with a limited toxicity towards normal cells and tissues [12][13][14][15]. In fact, the effectiveness of PARPi in the BRCA1/2-mutated breast/ovarian tumors has initiated an era of personalized medicine with the utilization of PARPi [32][33][34]. Mechanistically, mutations in BRCA1/2 inactivate the HR pathway, and in order to survive, BRCA1/2-mutated cancer cells require the activity of PARP1 in BER and/or a-NHEJ, to prevent the formation of DSBs from unrepaired DNA single-strand breaks (SSBs) during DNA replication. Therefore, the inhibition of PARP1 by PARPi results in stalled replication forks and the accumulation of lethal DSBs, leading to cell death.

Recently, another mechanism has been proposed to regulate PARPi-triggered synthetic lethality in BRCA1/2-mutated cells: the single-strand DNA replication gaps [35][36]. Enhanced replication gaps in BRCA1/2-deficient cells were coupled with PARPi sensitivity. Besides working effectively in BRCA1/2-mutated cancers, PARPi-mediated synthetic lethality is capable of sensitizing c-NHEJ-deficient cancer cells. For example, the downregulation of LIG4 (involved in the c-NHEJ pathway to perform DNA ligation) induced the sensitivity of melanoma cells to PARPi (olaparib), without a cytotoxic effect on normal melanocytes [37].

Initially, the major mechanism of the efficiency of PARPi has been associated with the interference of the accessibility of NAD+ to the PARP1 catalytic domain, leading to the inactivation of the PARylation process and the inhibition of BER and/or a-NHEJ [38]. However, recent studies have shown that the inhibition of the catalytic activity of PARPs is not the only mechanism triggering synthetic lethality [39]. Additionally, PARPi can cause the trapping of PARP1 (and probably also PARP2), resulting in DNA replication, transcriptional arrest and the accumulation of DSBs. The magnitude of synthetic lethality triggered by PARPi corresponds to their capability of PARP1 entrapment [40]. PARPi talazoparib (also known as BMN673) has been reported to be approximately 20–200 times more efficient than previous versions of PARPi, such as olaparib [41]. The elevated efficacy of talazoparib results from its enhanced PARP1-trapping capacity, thus making talazoparib one of the best PARP-trapping agents among currently available PARPi [42].

3. PARPi in Clinical Trials of BRCA1/2-Mutated Cancers

Olaparib (commercial name—Lynparza®) is the first pharmacological PARPi that has been administered in clinical trials. Until now, olaparib is the most common PARPi used in BRCA1/2-deficient cancers. Historically, olaparib became the first PARPi approved by the FDA in December 2014, based on its significant efficacy in the treatment of relapsed ovarian cancer individuals with BRCA1/2 mutations [43]. In August 2017, olaparib obtained the second approval from the FDA as an extensive therapy for patients with recurrent fallopian tube, peritoneal or epithelial ovarian cancer who have achieved partial or complete remission after the systematic standard chemotherapy [44][45]. Additionally, the potential of olaparib in the anticancer therapy has been extended in January 2018, when the FDA licensed the PARPi as a therapeutic strategy for germline BRCA1/2-mutated metastatic breast cancer patients who previously received chemotherapy [46]. This marked olaparib as the first FDA-approved compound working effectively in individuals with hereditary breast cancer. Besides the trials in BRCA1/2-mutated breast and ovarian cancer, olaparib was also granted approval by the FDA in different solid tumors. This includes BRCA1/2-mutated metastatic pancreatic cancer in 2019 [47], fallopian and primary peritoneal carcinoma in a combinational intervention with bevacizumab [48] and HR-deficient metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer in 2020 [49].

In addition, two other PARP inhibitors, rucaparib and niraparib, which also target polymerase enzymatic activity, have obtained approval for clinical trials. In detail, the FDA accepted the clinical trials of rucaparib for BRCA1/2-mutated advanced ovarian carcinomas undergoing multiple chemotherapy treatments in 2016 [50], reoccurring ovarian, fallopian and primary peritoneal carcinoma without BRCA1/2 mutational status in 2018 [51] and BRCA1/2-mutated metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer in 2020 [52]. Meanwhile, niraparib achieved the approval of the FDA for reoccurring ovarian, fallopian and primary peritoneal carcinoma with complete or partial chemotherapeutic response in 2017 [53], HR-deficient reoccurring ovarian, fallopian and primary peritoneal carcinoma without chemotherapeutic response in 2019 [54] and advanced ovarian carcinomas with complete or partial chemotherapeutic response in 2020 [55].

On the other hand, based on the significant PARP1 trapping capacity, talazoparib has been clinically employed in breast cancer patients with germline mutations of BRCA1/2 and other types of cancer that contain impaired DNA damage responses [22][56]. For example, phase III clinical trials of talazoparib demonstrated the increased overall survival rate of metastatic breast cancer patients [57], and it has been approved by the FDA since 2018 [58]. Besides talazoparib, another orally available PARPi (veliparib) is currently undergoing clinical trials [59]. It shows the best selectivity against PARP1/2/3 catalysis, though this PARPi exhibits a limited efficacy of PARP1 trapping [60]. This demonstrated that PARPi, which exerts a more potent and selective inhibitory effect on the PARylation process, is also capable of entering clinical trials.

4. Therapeutic Potential of PARPi in Hematopoietic Malignancies

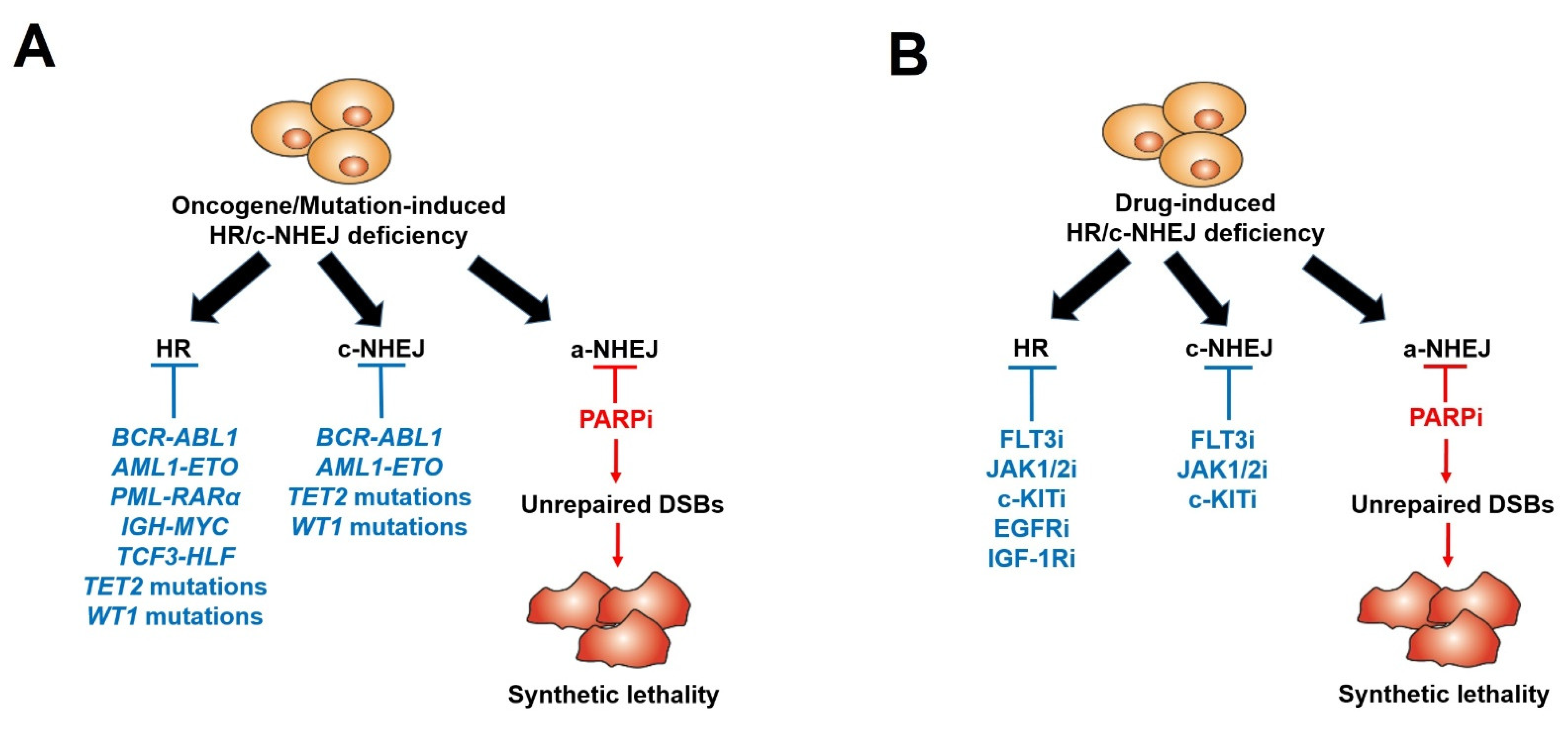

Many recent studies, including ours, have shown that even if BRCA1/2 mutations are rarely detected in leukemias, PARPi-induced synthetic lethality can be effectively exploited in BRCA1/2-deficient hematopoietic malignant cells. Using a comprehensive Gene Expression and Mutation Analysis strategy, researchers were able to identify acute myeloid leukemias/acute lymphoblastic leukemias (AMLs/ALLs) that displayed HR and/or c-NHEJ deficiency and were also sensitive to PARPi [18]. These DSB repair defects were detected by direct measurements of the expression of HR and c-NHEJ genes by mRNA microarrays, real-time PCR and/or flow cytometry. In addition, genetic alterations inducing hematopoietic malignancies, such as oncogenes driving myeloid and lymphoid malignancies, including AML1-ETO (also known as RUNX1-RUNX1T1), BCR-ABL1, PML-RARα, TCF3-HLF, IDH1/2mut and IGH-MYC, and loss-of-function mutations in tumor suppressor genes (e.g., TET2, WT1), can lead to the deregulation of HR and/or c-NHEJ activity, thus rendering cells susceptible to a synthetically lethal effect triggered by PARPi [23][24][25][61][62][63][64][65][66][67][68][69][70][71][72][73] (Figure 1A and Table 1). In addition, mutations in the core cohesion complex gene STAG2 (Stromal Antigen 2) induce DNA damage, stalled replication forks and a high genetic dependency on PARP1 in AML/myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) cells. Therefore, those cells are sensitive to PARPi talazoparib both in vitro and in vivo; however, the mechanism remains unexplored [74].

Figure 1. Scheme of PARP inhibitors administered in hematopoietic malignancies and other tumors displaying HR/c-NHEJ deficiency induced by oncogenes/mutations (A) and tyrosine kinase inhibitors (B).

Table 1. Oncogenes/Mutations inducing HR/c-NHEJ deficiency.

| Disease | Oncogene/Mutation-Induced HR/c-NHEJ Deficiency | Deregulated Protein | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| CML | BCR-ABL1 | BRCA1, DNA-PKcs | [18][23][64][68][73] |

| AML | AML1-ETO | BRCA1, BRCA2, Ku70 | [25] |

| AML | PML-RARα | BRCA2, RAD51C | [25][69] |

| Burkitt lymphoma | IGH-MYC | BRCA2 | [24] |

| AML | IDH1/IDH2 mutants | ATM | [66][70][71] |

| AML/ALL | TCF3-HLF | BRCA1, BRCA2 | [62] |

| AML | FLT3ITD+TET2 mutant | BRCA1, LIG4 | [67] |

| AML | FLT3ITD+WT1 mutant | BRCA1, LIG4 | [67] |

| AML/MDS | TET2 mutant | BRCA1 | [72] |

Furthermore, researchers and others described that those malignant hematopoietic cells expressing oncogenic tyrosine kinases (OTK) (e.g., BCR-ABL1, FLT3(ITD), JAK2(V617F)) spontaneously accumulate high levels of oxidative DNA damage and DSBs due to the increase in ROS production [75][76][77]. However, OTK-positive cells were capable of escaping from the cytotoxic effect of DSBs due to enhanced/modulated DSB repair. Remarkably, the inhibition of these OTKs by FDA-approved specific tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKi) (JAK1/2 inhibitor ruxolitinib, FLT3 inhibitor quizartinib, ABL1 inhibitor imatinib) resulted in acute HR/c-NHEJ deficiency (due to the downregulation of BRCA1, BRCA2, RAD51 and/or LIG4) and the sensitivity to PARPi (Figure 1B) (Table 2). Therefore, the combination of TKi and PARPi was capable of eradicating both proliferating and quiescent malignant hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells [18][27][28][29][61]. All these promising results have made up a rationale for clinical trials with PARPi in patients with leukemias and other related hematopoietic malignancies [26].

Table 2. Therapeutic drugs inducing HR/c-NHEJ deficiency.

| Disease | Drug-Induced HR/c-NHEJ Deficiency |

Deregulated Protein | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Myeloproliferative neoplams [JAK2(V617F)] |

JAK1/2 kinase inhibitor (Ruxolitinib) | BRCA1, RAD51C, LIG4 | [27] |

| AML [FLT3(ITD)] |

FLT3 kinase inhibitor (Quizartinib) | BRCA1, BRCA2, PALB2, RAD51, LIG4 | [28] |

| AML [c-KIT(N822K)] |

c-KIT kinase inhibitor (Avapritinib) | BRCA1, BRCA2, DNA-PKcs | [29] |

| Breast cancer | EGFR kinase inhibitor (Lapatinib) | BRCA1 | [30] |

| Breast and ovarian cancers | IGF-1R kinase inhibitor | RAD51 | [31] |

As a result, the first trial (NCT01399840) of PARPi in hematopoietic malignancies began in 2014, when the efficacy of talazoparib was tested in 25 AML/MDS patients and 8 other individuals with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and mantle cell lymphoma [78]. During 2017, there were three phase I clinical trials registered, including a combinational therapy of veliparib + temozolomide in 48 patients with relapsed/refractory AML (NCT01139970) [79], veliparib combination with topotecan and carboplatin in a clinical study of 99 patients with relapsed/refractory AML, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia or aggressive myeloproliferative neoplasms (NCT00588991) [80], and olaparib in 15 patients with relapsed CLL, T-prolymphocytic leukemia or mantle cell lymphoma [81]. In 2021, the results of a clinical trial (NCT04326023) examining the efficiency of PARP inhibitors, including olaparib, rucaparib, niraparib, talazoparib and veliparib, in 178 patients with MDS and AML were reported [82]. Although 104 in 178 MDS/AML participants were recorded with positive outcomes, PARPi increased the risk of MDS/AML in adults over 18 [82]. Additionally, a phase I clinical trial of the DNA methyltransferase inhibitor decitabine and talazoparib has been demonstrated in 25 patients with relapsed/refractory AML [83].

References

- Kaelin, W.G., Jr. The concept of synthetic lethality in the context of anticancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2005, 5, 689–698.

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674.

- Dudas, A.; Chovanec, M. DNA double-strand break repair by homologous recombination. Mutat. Res. 2004, 566, 131–167.

- Yang, H.; Zhong, Y.; Peng, C.; Chen, J.Q.; Tian, D. Important role of indels in somatic mutations of human cancer genes. BMC Med. Genet. 2010, 11, 128.

- Featherstone, C.; Jackson, S.P. DNA double-strand break repair. Curr. Biol. CB 1999, 9, R759–R761.

- Mao, Z.; Bozzella, M.; Seluanov, A.; Gorbunova, V. Comparison of nonhomologous end joining and homologous recombination in human cells. DNA Repair 2008, 7, 1765–1771.

- Humphryes, N.; Hochwagen, A. A non-sister act: Recombination template choice during meiosis. Exp. Cell Res. 2014, 329, 53–60.

- Caldecott, K.W. Mammalian single-strand break repair: Mechanisms and links with chromatin. DNA Repair 2007, 6, 443–453.

- Dueva, R.; Iliakis, G. Alternative pathways of non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) in genomic instability and cancer. Transl. Cancer Res. 2013, 2, 163–177.

- Truong, L.N.; Li, Y.; Shi, L.Z.; Hwang, P.Y.-H.; He, J.; Wang, H.; Razavian, N.; Berns, M.W.; Wu, X. Microhomology-mediated End Joining and Homologous Recombination share the initial end resection step to repair DNA double-strand breaks in mammalian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 7720–7725.

- Kent, T.; Chandramouly, G.; McDevitt, S.M.; Ozdemir, A.Y.; Pomerantz, R.T. Mechanism of microhomology-mediated end-joining promoted by human DNA polymerase theta. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2015, 22, 230–237.

- Farmer, H.; McCabe, N.; Lord, C.J.; Tutt, A.N.; Johnson, D.A.; Richardson, T.B.; Santarosa, M.; Dillon, K.J.; Hickson, I.; Knights, C.; et al. Targeting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells as a therapeutic strategy. Nature 2005, 434, 917–921.

- Bryant, H.E.; Schultz, N.; Thomas, H.D.; Parker, K.M.; Flower, D.; Lopez, E.; Kyle, S.; Meuth, M.; Curtin, N.J.; Helleday, T. Specific killing of BRCA2-deficient tumours with inhibitors of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. Nature 2005, 434, 913–917.

- Yap, T.A.; Sandhu, S.K.; Carden, C.P.; de Bono, J.S. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors: Exploiting a synthetic lethal strategy in the clinic. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2011, 61, 31–49.

- Rottenberg, S.; Jaspers, J.E.; Kersbergen, A.; van der Burg, E.; Nygren, A.O.; Zander, S.A.; Derksen, P.W.; de Bruin, M.; Zevenhoven, J.; Lau, A.; et al. High sensitivity of BRCA1-deficient mammary tumors to the PARP inhibitor AZD2281 alone and in combination with platinum drugs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 17079–17084.

- Fok, J.H.L.; Ramos-Montoya, A.; Vazquez-Chantada, M.; Wijnhoven, P.W.G.; Follia, V.; James, N.; Farrington, P.M.; Karmokar, A.; Willis, S.E.; Cairns, J.; et al. AZD7648 is a potent and selective DNA-PK inhibitor that enhances radiation, chemotherapy and olaparib activity. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5065.

- Chan, C.Y.; Tan, K.V.; Cornelissen, B. PARP Inhibitors in Cancer Diagnosis and Therapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 1585–1594.

- Nieborowska-Skorska, M.; Sullivan, K.; Dasgupta, Y.; Podszywalow-Bartnicka, P.; Hoser, G.; Maifrede, S.; Martinez, E.; Di Marcantonio, D.; Bolton-Gillespie, E.; Cramer-Morales, K.; et al. Gene expression and mutation-guided synthetic lethality eradicates proliferating and quiescent leukemia cells. J. Clin. Investig. 2017, 127, 2392–2406.

- Fong, P.C.; Boss, D.S.; Yap, T.A.; Tutt, A.; Wu, P.; Mergui-Roelvink, M.; Mortimer, P.; Swaisland, H.; Lau, A.; O'Connor, M.J.; et al. Inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase in tumors from BRCA mutation carriers. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 361, 123–134.

- Gunjur, A. Talazoparib for BRCA-mutated advanced breast cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2018, 19, e511.

- Hurvitz, S.A.; Gonçalves, A.; Rugo, H.S.; Lee, K.H.; Fehrenbacher, L.; Mina, L.A.; Diab, S.; Blum, J.L.; Chakrabarti, J.; Elmeliegy, M.; et al. Talazoparib in Patients with a Germline BRCA-Mutated Advanced Breast Cancer: Detailed Safety Analyses from the Phase III EMBRACA Trial. Oncol. 2019, 25, e439–e450.

- Litton, J.K.; Rugo, H.S.; Ettl, J.; Hurvitz, S.A.; Gonçalves, A.; Lee, K.H.; Fehrenbacher, L.; Yerushalmi, R.; Mina, L.A.; Martin, M.; et al. Talazoparib in Patients with Advanced Breast Cancer and a Germline BRCA Mutation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 753–763.

- Podszywalow-Bartnicka, P.; Wolczyk, M.; Kusio-Kobialka, M.; Wolanin, K.; Skowronek, K.; Nieborowska-Skorska, M.; Dasgupta, Y.; Skorski, T.; Piwocka, K. Downregulation of BRCA1 protein in BCR-ABL1 leukemia cells depends on stress-triggered TIAR-mediated suppression of translation. Cell Cycle 2014, 13, 3727–3741.

- Maifrede, S.; Martin, K.; Podszywalow-Bartnicka, P.; Sullivan-Reed, K.; Langer, S.K.; Nejati, R.; Dasgupta, Y.; Hulse, M.; Gritsyuk, D.; Nieborowska-Skorska, M.; et al. IGH/MYC Translocation Associates with BRCA2 Deficiency and Synthetic Lethality to PARP1 Inhibitors. Mol. Cancer Res. 2017, 15, 967–972.

- Esposito, M.T.; Zhao, L.; Fung, T.K.; Rane, J.K.; Wilson, A.; Martin, N.; Gil, J.; Leung, A.Y.; Ashworth, A.; So, C.W. Synthetic lethal targeting of oncogenic transcription factors in acute leukemia by PARP inhibitors. Nat. Med. 2015, 21, 1481–1490.

- Faraoni, I.; Giansanti, M.; Voso, M.T.; Lo-Coco, F.; Graziani, G. Targeting ADP-ribosylation by PARP inhibitors in acute myeloid leukaemia and related disorders. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2019, 167, 133–148.

- Nieborowska-Skorska, M.; Maifrede, S.; Dasgupta, Y.; Sullivan, K.; Flis, S.; Le, B.V.; Solecka, M.; Belyaeva, E.A.; Kubovcakova, L.; Nawrocki, M.; et al. Ruxolitinib-induced defects in DNA repair cause sensitivity to PARP inhibitors in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood 2017, 130, 2848–2859.

- Maifrede, S.; Nieborowska-Skorska, M.; Sullivan-Reed, K.; Dasgupta, Y.; Podszywalow-Bartnicka, P.; Le, B.V.; Solecka, M.; Lian, Z.; Belyaeva, E.A.; Nersesyan, A.; et al. Tyrosine kinase inhibitor-induced defects in DNA repair sensitize FLT3(ITD)-positive leukemia cells to PARP1 inhibitors. Blood 2018, 132, 67–77.

- Nieborowska-Skorska, M.; Paietta, E.M.; Levine, R.L.; Fernandez, H.F.; Tallman, M.S.; Litzow, M.R.; Skorski, T. Inhibition of the mutated c-KIT kinase in AML1-ETO-positive leukemia cells restores sensitivity to PARP inhibitor. Blood Adv. 2019, 3, 4050–4054.

- Nowsheen, S.; Cooper, T.; Stanley, J.A.; Yang, E.S. Synthetic Lethal Interactions between EGFR and PARP Inhibition in Human Triple Negative Breast Cancer Cells. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e46614.

- Amin, O.; Beauchamp, M.-C.; Nader, P.A.; Laskov, I.; Iqbal, S.; Philip, C.-A.; Yasmeen, A.; Gotlieb, W.H. Suppression of Homologous Recombination by insulin-like growth factor-1 inhibition sensitizes cancer cells to PARP inhibitors. BMC Cancer 2015, 15, 817.

- Iglehart, J.D.; Silver, D.P. Synthetic lethality--a new direction in cancer-drug development. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 361, 189–191.

- McCann, K.E.; Hurvitz, S.A. Advances in the use of PARP inhibitor therapy for breast cancer. Drugs Context 2018, 7, 212540.

- Mittica, G.; Ghisoni, E.; Giannone, G.; Genta, S.; Aglietta, M.; Sapino, A.; Valabrega, G. PARP Inhibitors in Ovarian Cancer. Recent Pat. Anticancer Drug Discov. 2018, 13, 392–410.

- Cong, K.; Peng, M.; Kousholt, A.N.; Lee, W.T.C.; Lee, S.; Nayak, S.; Krais, J.; VanderVere-Carozza, P.S.; Pawelczak, K.S.; Calvo, J.; et al. Replication gaps are a key determinant of PARP inhibitor synthetic lethality with BRCA deficiency. Mol. Cell 2021, 81, 3128–3144.e3127.

- Panzarino, N.J.; Krais, J.J.; Cong, K.; Peng, M.; Mosqueda, M.; Nayak, S.U.; Bond, S.M.; Calvo, J.A.; Doshi, M.B.; Bere, M.; et al. Replication Gaps Underlie BRCA Deficiency and Therapy Response. Cancer Res. 2021, 81, 1388–1397.

- Czyz, M.; Toma, M.; Gajos-Michniewicz, A.; Majchrzak, K.; Hoser, G.; Szemraj, J.; Nieborowska-Skorska, M.; Cheng, P.; Gritsyuk, D.; Levesque, M.; et al. PARP1 inhibitor olaparib (Lynparza) exerts synthetic lethal effect against ligase 4-deficient melanomas. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 75551–75560.

- Curtin, N.J.; Szabo, C. Therapeutic applications of PARP inhibitors: Anticancer therapy and beyond. Mol. Aspects Med. 2013, 34, 1217–1256.

- Murai, J.; Huang, S.Y.; Das, B.B.; Renaud, A.; Zhang, Y.; Doroshow, J.H.; Ji, J.; Takeda, S.; Pommier, Y. Trapping of PARP1 and PARP2 by Clinical PARP Inhibitors. Cancer Res. 2012, 72, 5588–5599.

- Hopkins, T.A.; Ainsworth, W.B.; Ellis, P.A.; Donawho, C.K.; DiGiammarino, E.L.; Panchal, S.C.; Abraham, V.C.; Algire, M.A.; Shi, Y.; Olson, A.M.; et al. PARP1 Trapping by PARP Inhibitors Drives Cytotoxicity in Both Cancer Cells and Healthy Bone Marrow. Mol. Cancer Res. 2019, 17, 409–419.

- Murai, J.; Huang, S.Y.; Renaud, A.; Zhang, Y.; Ji, J.; Takeda, S.; Morris, J.; Teicher, B.; Doroshow, J.H.; Pommier, Y. Stereospecific PARP trapping by BMN 673 and comparison with olaparib and rucaparib. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2014, 13, 433–443.

- Meehan, R.S.; Chen, A.P. New treatment option for ovarian cancer: PARP inhibitors. Gynecol. Oncol. Res. Pract. 2016, 3, 3.

- Kim, G.; Ison, G.; McKee, A.E.; Zhang, H.; Tang, S.; Gwise, T.; Sridhara, R.; Lee, E.; Tzou, A.; Philip, R.; et al. FDA Approval Summary: Olaparib Monotherapy in Patients with Deleterious Germline BRCA-Mutated Advanced Ovarian Cancer Treated with Three or More Lines of Chemotherapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 4257–4261.

- Pujade-Lauraine, E.; Ledermann, J.A.; Selle, F.; Gebski, V.; Penson, R.T.; Oza, A.M.; Korach, J.; Huzarski, T.; Poveda, A.; Pignata, S.; et al. Olaparib tablets as maintenance therapy in patients with platinum-sensitive, relapsed ovarian cancer and a BRCA1/2 mutation (SOLO2/ENGOT-Ov21): A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, 1274–1284.

- Friedlander, M.; Matulonis, U.; Gourley, C.; du Bois, A.; Vergote, I.; Rustin, G.; Scott, C.; Meier, W.; Shapira-Frommer, R.; Safra, T.; et al. Long-term efficacy, tolerability and overall survival in patients with platinum-sensitive, recurrent high-grade serous ovarian cancer treated with maintenance olaparib capsules following response to chemotherapy. Br. J. Cancer 2018, 119, 1075–1085.

- Robson, M.; Im, S.-A.; Senkus, E.; Xu, B.; Domchek, S.M.; Masuda, N.; Delaloge, S.; Li, W.; Tung, N.; Armstrong, A.; et al. Olaparib for Metastatic Breast Cancer in Patients with a Germline BRCA Mutation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 523–533.

- Golan, T.; Hammel, P.; Reni, M.; van Cutsem, E.; Macarulla, T.; Hall, M.J.; Park, J.O.; Hochhauser, D.; Arnold, D.; Oh, D.Y.; et al. Maintenance Olaparib for Germline BRCA-Mutated Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 317–327.

- Ray-Coquard, I.; Pautier, P.; Pignata, S.; Pérol, D.; González-Martín, A.; Berger, R.; Fujiwara, K.; Vergote, I.; Colombo, N.; Mäenpää, J.; et al. Olaparib plus Bevacizumab as First-Line Maintenance in Ovarian Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 2416–2428.

- De Bono, J.; Mateo, J.; Fizazi, K.; Saad, F.; Shore, N.; Sandhu, S.; Chi, K.N.; Sartor, O.; Agarwal, N.; Olmos, D.; et al. Olaparib for Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 2091–2102.

- Oza, A.M.; Tinker, A.V.; Oaknin, A.; Shapira-Frommer, R.; McNeish, I.A.; Swisher, E.M.; Ray-Coquard, I.; Bell-McGuinn, K.; Coleman, R.L.; O'Malley, D.M.; et al. Antitumor activity and safety of the PARP inhibitor rucaparib in patients with high-grade ovarian carcinoma and a germline or somatic BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation: Integrated analysis of data from Study 10 and ARIEL2. Gynecol. Oncol. 2017, 147, 267–275.

- Coleman, R.L.; Oza, A.M.; Lorusso, D.; Aghajanian, C.; Oaknin, A.; Dean, A.; Colombo, N.; Weberpals, J.I.; Clamp, A.; Scambia, G.; et al. Rucaparib maintenance treatment for recurrent ovarian carcinoma after response to platinum therapy (ARIEL3): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2017, 390, 1949–1961.

- Abida, W.; Campbell, D.; Patnaik, A.; Sautois, B.; Shapiro, J.; Vogelzang, N.J.; Bryce, A.H.; McDermott, R.; Ricci, F.; Rowe, J.; et al. 846PD - Preliminary results from the TRITON2 study of rucaparib in patients (pts) with DNA damage repair (DDR)-deficient metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC): Updated analyses. Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, v327–v328.

- Mirza, M.R.; Monk, B.J.; Herrstedt, J.; Oza, A.M.; Mahner, S.; Redondo, A.; Fabbro, M.; Ledermann, J.A.; Lorusso, D.; Vergote, I.; et al. Niraparib Maintenance Therapy in Platinum-Sensitive, Recurrent Ovarian Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 2154–2164.

- Moore, K.N.; Secord, A.A.; Geller, M.A.; Miller, D.S.; Cloven, N.; Fleming, G.F.; Wahner Hendrickson, A.E.; Azodi, M.; DiSilvestro, P.; Oza, A.M.; et al. Niraparib monotherapy for late-line treatment of ovarian cancer (QUADRA): A multicentre, open-label, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, 636–648.

- González-Martín, A.; Pothuri, B.; Vergote, I.; DePont Christensen, R.; Graybill, W.; Mirza, M.R.; McCormick, C.; Lorusso, D.; Hoskins, P.; Freyer, G.; et al. Niraparib in Patients with Newly Diagnosed Advanced Ovarian Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 2391–2402.

- De Bono, J.; Ramanathan, R.K.; Mina, L.; Chugh, R.; Glaspy, J.; Rafii, S.; Kaye, S.; Sachdev, J.; Heymach, J.; Smith, D.C.; et al. Phase I, Dose-Escalation, Two-Part Trial of the PARP Inhibitor Talazoparib in Patients with Advanced Germline BRCA1/2 Mutations and Selected Sporadic Cancers. Cancer Discov. 2017, 7, 620–629.

- Exman, P.; Barroso-Sousa, R.; Tolaney, S.M. Evidence to date: Talazoparib in the treatment of breast cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2019, 12, 5177–5187.

- Ettl, J.; Quek, R.G.W.; Lee, K.H.; Rugo, H.S.; Hurvitz, S.; Gonçalves, A.; Fehrenbacher, L.; Yerushalmi, R.; Mina, L.A.; Martin, M.; et al. Quality of life with talazoparib versus physician's choice of chemotherapy in patients with advanced breast cancer and germline BRCA1/2 mutation: Patient-reported outcomes from the EMBRACA phase III trial. Ann. Oncol. Off. J. Eur. Soc. Med. Oncol. 2018, 29, 1939–1947.

- Coleman, R.L.; Fleming, G.F.; Brady, M.F.; Swisher, E.M.; Steffensen, K.D.; Friedlander, M.; Okamoto, A.; Moore, K.N.; Efrat Ben-Baruch, N.; Werner, T.L.; et al. Veliparib with First-Line Chemotherapy and as Maintenance Therapy in Ovarian Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 2403–2415.

- Murai, J.; Pommier, Y. Classification of PARP Inhibitors Based on PARP Trapping and Catalytic Inhibition, and Rationale for Combinations with Topoisomerase I Inhibitors and Alkylating Agents. In PARP Inhibitors for Cancer Therapy; Curtin, N.J., Sharma, R.A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 261–274.

- Maifrede, S.; Martinez, E.; Nieborowska-Skorska, M.; Di Marcantonio, D.; Hulse, M.; Le, B.V.; Zhao, H.; Piwocka, K.; Tempera, I.; Sykes, S.M.; et al. MLL-AF9 leukemias are sensitive to PARP1 inhibitors combined with cytotoxic drugs. Blood Adv. 2017, 1, 1467–1472.

- Piao, J.; Takai, S.; Kamiya, T.; Inukai, T.; Sugita, K.; Ohyashiki, K.; Delia, D.; Masutani, M.; Mizutani, S.; Takagi, M. Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitors selectively induce cytotoxicity in TCF3-HLF-positive leukemic cells. Cancer Lett. 2017, 386, 131–140.

- Molenaar, R.J.; Radivoyevitch, T.; Nagata, Y.; Khurshed, M.; Przychodzen, B.; Makishima, H.; Xu, M.; Bleeker, F.E.; Wilmink, J.W.; Carraway, H.E.; et al. IDH1/2 Mutations Sensitize Acute Myeloid Leukemia to PARP Inhibition and This Is Reversed by IDH1/2-Mutant Inhibitors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 24, 1705–1715.

- Deutsch, E.; Jarrousse, S.; Buet, D.; Dugray, A.; Bonnet, M.L.; Vozenin-Brotons, M.C.; Guilhot, F.; Turhan, A.G.; Feunteun, J.; Bourhis, J. Down-regulation of BRCA1 in BCR-ABL-expressing hematopoietic cells. Blood 2003, 101, 4583–4588.

- Cimmino, L.; Dolgalev, I.; Wang, Y.; Yoshimi, A.; Martin, G.H.; Wang, J.; Ng, V.; Xia, B.; Witkowski, M.T.; Mitchell-Flack, M.; et al. Restoration of TET2 Function Blocks Aberrant Self-Renewal and Leukemia Progression. Cell 2017, 170, 1079–1095.e1020.

- Inoue, S.; Li, W.Y.; Tseng, A.; Beerman, I.; Elia, A.J.; Bendall, S.C.; Lemonnier, F.; Kron, K.J.; Cescon, D.W.; Hao, Z.; et al. Mutant IDH1 Downregulates ATM and Alters DNA Repair and Sensitivity to DNA Damage Independent of TET2. Cancer Cell 2016, 30, 337–348.

- Maifrede, S.; Le, B.V.; Nieborowska-Skorska, M.; Golovine, K.; Sullivan-Reed, K.; Dunuwille, W.M.B.; Nacson, J.; Hulse, M.; Keith, K.; Madzo, J.; et al. TET2 and DNMT3A Mutations Exert Divergent Effects on DNA Repair and Sensitivity of Leukemia Cells to PARP Inhibitors. Cancer Res. 2021, 81, 5089–5101.

- Dkhissi, F.; Aggoune, D.; Pontis, J.; Sorel, N.; Piccirilli, N.; LeCorf, A.; Guilhot, F.; Chomel, J.C.; Ait-Si-Ali, S.; Turhan, A.G. The downregulation of BAP1 expression by BCR-ABL reduces the stability of BRCA1 in chronic myeloid leukemia. Exp. Hematol. 2015, 43, 775–780.

- Alcalay, M.; Meani, N.; Gelmetti, V.; Fantozzi, A.; Fagioli, M.; Orleth, A.; Riganelli, D.; Sebastiani, C.; Cappelli, E.; Casciari, C.; et al. Acute myeloid leukemia fusion proteins deregulate genes involved in stem cell maintenance and DNA repair. J. Clin. Investig. 2003, 112, 1751–1761.

- Sulkowski Parker, L.; Corso Christopher, D.; Robinson Nathaniel, D.; Scanlon Susan, E.; Purshouse Karin, R.; Bai, H.; Liu, Y.; Sundaram Ranjini, K.; Hegan Denise, C.; Fons Nathan, R.; et al. 2-Hydroxyglutarate produced by neomorphic IDH mutations suppresses homologous recombination and induces PARP inhibitor sensitivity. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017, 9, eaal2463.

- Sulkowski, P.L.; Oeck, S.; Dow, J.; Economos, N.G.; Mirfakhraie, L.; Liu, Y.; Noronha, K.; Bao, X.; Li, J.; Shuch, B.M.; et al. Oncometabolites suppress DNA repair by disrupting local chromatin signalling. Nature 2020, 582, 586–591.

- Chen, L.L.; Lin, H.P.; Zhou, W.J.; He, C.X.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Cheng, Z.L.; Song, J.B.; Liu, P.; Chen, X.Y.; Xia, Y.K.; et al. SNIP1 Recruits TET2 to Regulate c-MYC Target Genes and Cellular DNA Damage Response. Cell Rep. 2018, 25, 1485–1500.e1484.

- Deutsch, E.; Dugray, A.; AbdulKarim, B.; Marangoni, E.; Maggiorella, L.; Vaganay, S.; M'Kacher, R.; Rasy, S.D.; Eschwege, F.; Vainchenker, W.; et al. BCR-ABL down-regulates the DNA repair protein DNA-PKcs. Blood 2001, 97, 2084–2090.

- Tothova, Z.; Valton, A.-L.; Gorelov, R.A.; Vallurupalli, M.; Krill-Burger, J.M.; Holmes, A.; Landers, C.C.; Haydu, J.E.; Malolepsza, E.; Hartigan, C.; et al. Cohesin mutations alter DNA damage repair and chromatin structure and create therapeutic vulnerabilities in MDS/AML. JCI Insight 2021, 6, e142149.

- Nowicki, M.O.; Falinski, R.; Koptyra, M.; Slupianek, A.; Stoklosa, T.; Gloc, E.; Nieborowska-Skorska, M.; Blasiak, J.; Skorski, T. BCR/ABL oncogenic kinase promotes unfaithful repair of the reactive oxygen species-dependent DNA double-strand breaks. Blood 2004, 104, 3746–3753.

- Nieborowska-Skorska, M.; Kopinski, P.K.; Ray, R.; Hoser, G.; Ngaba, D.; Flis, S.; Cramer, K.; Reddy, M.M.; Koptyra, M.; Penserga, T.; et al. Rac2-MRC-cIII-generated ROS cause genomic instability in chronic myeloid leukemia stem cells and primitive progenitors. Blood 2012, 119, 4253–4263.

- Marty, C.; Lacout, C.; Droin, N.; Le Couédic, J.P.; Ribrag, V.; Solary, E.; Vainchenker, W.; Villeval, J.L.; Plo, I. A role for reactive oxygen species in JAK2 V617F myeloproliferative neoplasm progression. Leukemia 2013, 27, 2187–2195.

- Mufti, G.; Estey, E.; Popat, R.; Mattison, R.; Menne, T.; Azar, J.; Bloor, A.; Gaymes, T.; Khwaja, A.; Juckett, M. Results of a phase 1 study of BMN 673, a potent and specific PARP-1/2 inhibitor, in patients with advanced hematological malignancies. In Haematologica, 2014; Ferrata Storti Foundation: Pavia, Italy, 2014; pp. 33–34.

- Gojo, I.; Beumer, J.H.; Pratz, K.W.; McDevitt, M.A.; Baer, M.R.; Blackford, A.L.; Smith, B.D.; Gore, S.D.; Carraway, H.E.; Showel, M.M.; et al. A Phase 1 Study of the PARP Inhibitor Veliparib in Combination with Temozolomide in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 697–706.

- Pratz, K.W.; Rudek, M.A.; Gojo, I.; Litzow, M.R.; McDevitt, M.A.; Ji, J.; Karnitz, L.M.; Herman, J.G.; Kinders, R.J.; Smith, B.D.; et al. A Phase I Study of Topotecan, Carboplatin and the PARP Inhibitor Veliparib in Acute Leukemias, Aggressive Myeloproliferative Neoplasms, and Chronic Myelomonocytic Leukemia. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 899–907.

- Pratt, G.; Yap, C.; Oldreive, C.; Slade, D.; Bishop, R.; Griffiths, M.; Dyer, M.J.S.; Fegan, C.; Oscier, D.; Pettitt, A.; et al. A multi-centre phase I trial of the PARP inhibitor olaparib in patients with relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, T-prolymphocytic leukaemia or mantle cell lymphoma. Br. J. Haematol. 2018, 182, 429–433.

- Morice, P.M.; Leary, A.; Dolladille, C.; Chrétien, B.; Poulain, L.; González-Martín, A.; Moore, K.; O'Reilly, E.M.; Ray-Coquard, I.; Alexandre, J. Myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukaemia in patients treated with PARP inhibitors: A safety meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials and a retrospective study of the WHO pharmacovigilance database. Lancet Haematol. 2021, 8, e122–e134.

- Baer, M.R.; Kogan, A.A.; Bentzen, S.M.; Mi, T.; Lapidus, R.G.; Duong, V.H.; Emadi, A.; Niyongere, S.; O'Connell, C.L.; Youngblood, B.A.; et al. Phase I Clinical Trial of DNA Methyltransferase Inhibitor Decitabine and PARP Inhibitor Talazoparib Combination Therapy in Relapsed/Refractory Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2022, 28, 1313–1322.

More

Information

Subjects:

Cell Biology; Biochemistry & Molecular Biology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

2.1K

Revisions:

3 times

(View History)

Update Date:

05 Dec 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No