Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ibrahim Halil Demirsoy | -- | 1860 | 2022-11-29 11:10:30 | | | |

| 2 | Catherine Yang | Meta information modification | 1860 | 2022-11-30 03:20:21 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Demirsoy, I.H.; Ferrari, G. The NK-1 Receptor Signaling in the Eye. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/37116 (accessed on 12 March 2026).

Demirsoy IH, Ferrari G. The NK-1 Receptor Signaling in the Eye. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/37116. Accessed March 12, 2026.

Demirsoy, Ibrahim Halil, Giulio Ferrari. "The NK-1 Receptor Signaling in the Eye" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/37116 (accessed March 12, 2026).

Demirsoy, I.H., & Ferrari, G. (2022, November 29). The NK-1 Receptor Signaling in the Eye. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/37116

Demirsoy, Ibrahim Halil and Giulio Ferrari. "The NK-1 Receptor Signaling in the Eye." Encyclopedia. Web. 29 November, 2022.

Copy Citation

Neurokinin-1 receptor (NK1R) signaling pathways play a crucial role in a number of biological processes in the eye. Specifically, in the ocular surface, their activity modulates epithelial integrity, inflammation, and generation of pain, while they have a role in visual processing in the retina. The NK1R is broadly expressed in the eye, in both ocular and non-ocular cells, such as leukocytes and neurons.

inflammation

corneal nerves

neurokinin-1 receptor

1. The Tachykinin Peptide Family and Its Receptors

The tachykinin peptide family is one of the largest peptide families in mammals, which regulates key biological processes, such as wound healing and inflammation. The tachykinin family consists of three genes and multiple neuropeptides. Neurokinin A (NKA), neuropeptide K (NPK), neuropeptide gamma (NPγ), and SP are expressed by the tachykinin precursor 1 (TAC1) gene through alternative splicing. Neurokinin B (NKB) is encoded by TAC3 gene. TAC4 gene expresses both hemokinin-1 (HK-1) and endokinins [1][2][3].

Tachykinin receptors genes (TACR1, TACR2, and TACR3) encode tachykinin 1 (NK1R), 2 (NK2R), and 3 (NK3R), respectively [4]. SP and HK-1 bind with high affinity to NK1R, NKA to NK2R, and NKB to NK3R. NKA and NKB bind to NK1R with low affinity (almost 100 times lower than SP). NKB and SP have a low affinity for NK2R, while NKA and SP exhibit low affinity for NK3R [5][6].

The NK1R is widely expressed in the eye, including ocular (corneal and retinal cells) and non-ocular cells (endothelial cells, leukocytes, and neurons) [3][7].

2. NK1R Structure

NK1R is a G-protein coupled receptor with extracellular glycosylation sites. It is located on the cell membrane and it contains 1221 nucleotides and 5 exons. It exists in two isoforms: one which is full length, and the other which is truncated and generated through alternative splicing [8][9][10].

The short carboxyl tail of the truncated form leads to partially active and less efficient SP-mediated NK1R signaling. This is mediated by the interaction with G-proteins and downstream pathways [11][12]. Specifically, the full-length isoform via SP rapidly activates the downstream RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK pathway and NF-κB. That increases IL-8 mRNA expression and intracellular Ca2+ concentrations. However, the NK1R truncated form is less effective in increasing IL-8 and intracellular calcium levels than the full form. Moreover, the activation of the truncated form has no effect on NF-κB expression. Finally, the truncated NK1R induces protein kinase C (PKC) downregulation and delays the activation of the RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK signaling pathway [11][13][14].

In addition to the effects of the carboxyl tail, the presence of glycosylation also impacts NK1R function. Indeed, the glycosylated NK1R is more stable probably because it favors NK1R anchoring to the cell membrane [15].

3. NK1R Signaling Activity

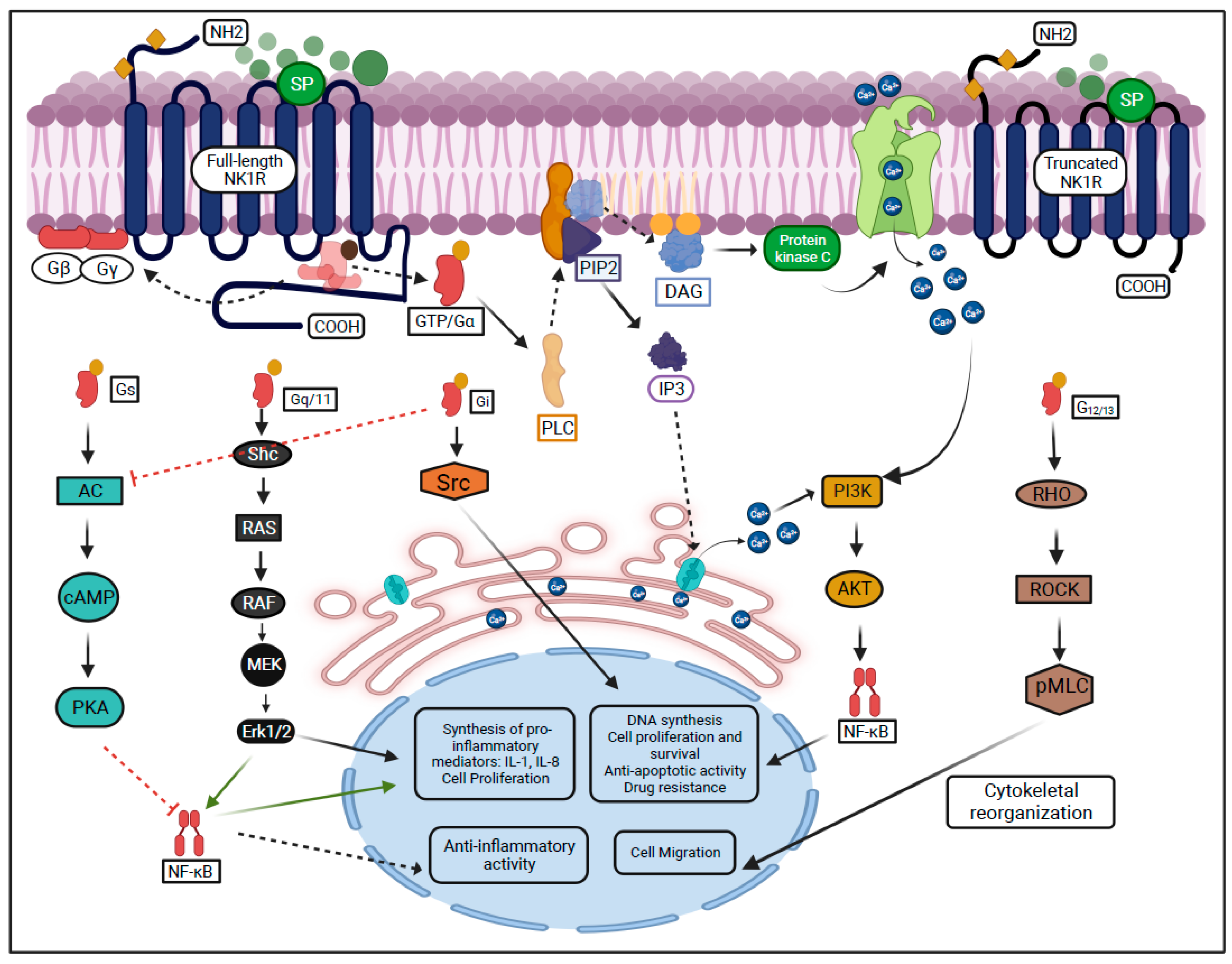

NK1R, a member of the G protein-coupled receptors superfamily regulates multiple signaling pathways in the eye. Substance P (SP) is a neuropeptide abundantly expressed on the ocular surface, including cornea and the retina [16][17][18], and has the highest affinity for NK1R. Dissociation of SP from NK1R is mediated by metalloproteases [19][20][21][22]. SP-NK1R interaction leads to increased cell proliferation and/or migration of corneal epithelial, endothelial cells, keratocytes, and leukocytes. Moreover, it stimulates corneal and retinal neurogenesis [3][23][24]. The binding of SP to the NK1R activates G proteins subunits (G-alpha, G-beta, and G-gamma), and leads to dissociation of the GDP/Gα subunit complex. The dissociated G-beta and G-gamma subunits remain bound to the cell membrane, whereas the GTP/Gα complex further leads to the activation of phospholipase C (PLC) and the production of second messengers [25][26]. Different active Gα subunits transmit the signals from the NK1R (Gq/11, Gs, G12/13, and Gi) [27].

The Gq/11 subunit is involved in the regulation of the MAPK-ERK pathway, leading to proliferation in neural progenitor cells [28]. The GTP/Gq/11 complex activates PLC, which stimulates the hydrolysis of phospholipids and the production of second messengers, such as DAG (diacylglycerol) and IP3 (inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate) [29]. DAG activates protein kinase C leading to an increase in intracellular Ca2+ concentrations, which is followed by the activation of phosphoinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), Akt serine/threonine kinase, and NF-κB. This leads to the synthesis of cytokines interleukin-1 and -8 (IL-1 and IL-8) [30][31]. Besides, the increased Ca2+ and DAG concentrations stimulate the phosphorylation of Ras/Raf proteins, which also promote cell proliferation and differentiation [32][33]. On the other hand, IP3 binds to inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors (IP3R) on the endoplasmic reticulum leading to increased Ca2+ concentrations in the cytosol (Figure 1) [34][35].

Figure 1. SP-mediated activation of NK1R and its downstream signaling pathways.

The GTP/G12/13 complex induces cytoskeletal remodeling through the Rock/Rho signaling pathway and leads to cell migration [32][36]. The G12/13 subunit leads to cell invasion and metastasis and has been described in breast and prostate cancer cell lines through the activation of the RhoA family [37][38].

The GTP/Gi complex activates the Src, which leads to the transactivation of the tropomyosin receptor kinases and promotes cell proliferation [39][40]. Previously, the Gi subunit has been reported to suppress cyclic AMP in vitro and activate directly SRC in murine fibroblast cells [41][42].

The Gs subunit is encoded by GNAS (guanine nucleotide binding protein) abundantly found in neuron precursors [30][43][44]. It has been reported that the Gs suppresses tumor progression in the medulloblastoma cell line and inhibits T lymphocyte proliferation in S49 lymphoma cells [45][46].

4. Distribution of NK1R in the Eye

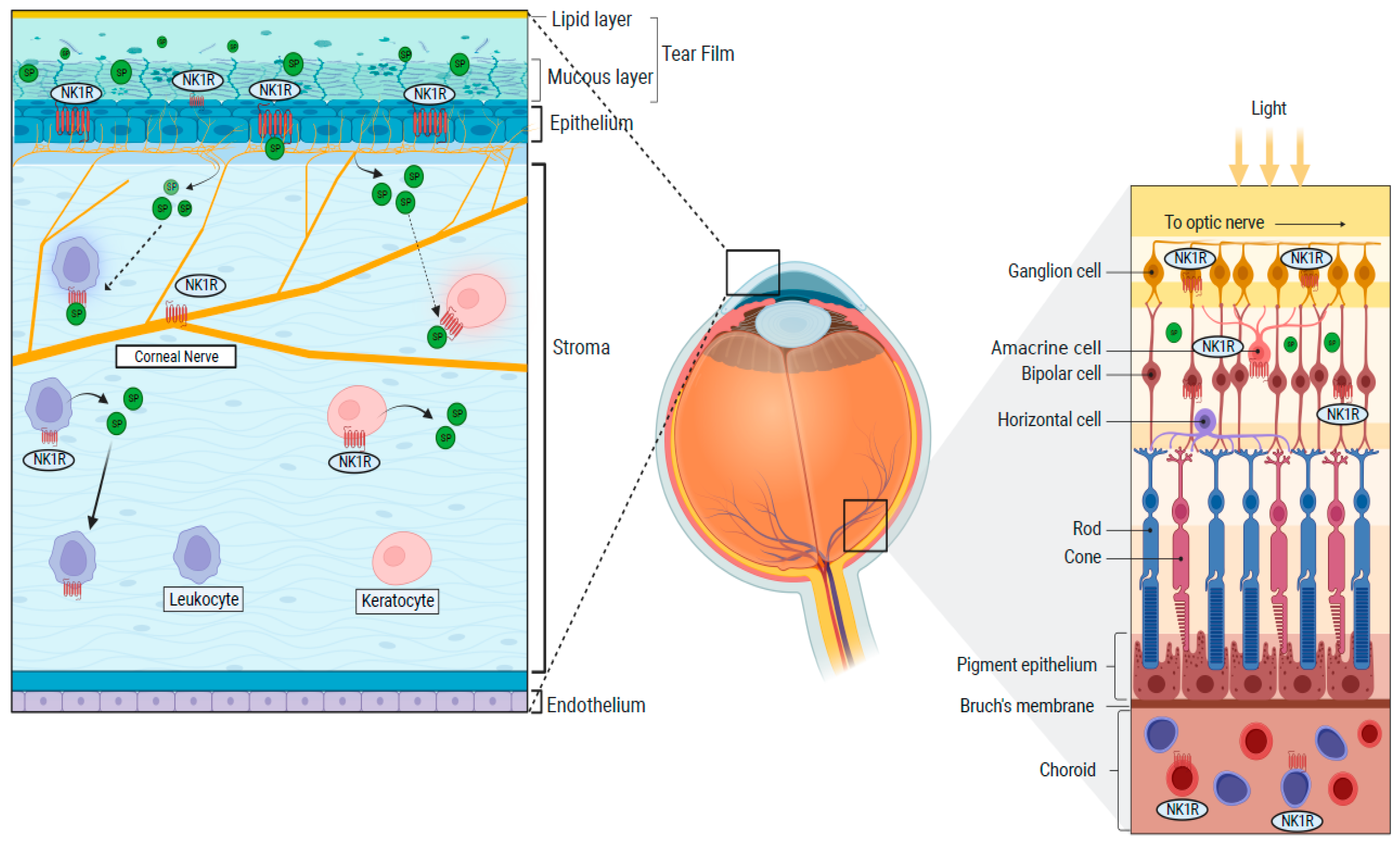

NK1R is broadly expressed in the cornea, iris, retina and choroid, conjunctiva, optic nerve, and lacrimal gland (Figure 2) [3][47][48][49].

Figure 2. Distributions of the NK1R in the cornea and the retina.

In the cornea, the epithelium, keratocytes, and corneal nerves express the NK1R [17][18][47]. Moreover, NK1R is expressed on limbal vasculature (on endothelial cells), where it promotes vascular permeability and lymphangiogenesis [3][50][51]. NK1R is also expressed on the iris sphincter smooth muscle fibers and vascular endothelial cells in the choroid [18][48]. The lacrimal gland also expresses NK1R, while the tear fluid contains large amounts of SP, both in mice and humans [52][53][54][55]. Finally, non-neural cells populating the eye, such as immune cells (T-cells, dendritic cells, lymphocytes, and monocytes), also show NK1R expression [3][56][57]. SP-mediated activation of the NK1 receptor induces different effects in different tissues. For instance, it modulates contraction in the iris sphincter muscle [58].

It should be noted, however, that the expression profiles and distribution of the full-length versus truncated form of NK1R remains unknown in the eye.

5. NK1R in Wound Healing, Inflammation, and Pain

Activation of the NK1R has been specifically studied in the pathophysiology of corneal epithelial wound healing, ocular surface inflammation, and pain [17][55][59][60][61].

5.1. NK1R and Corneal Epithelial Wound Healing

The corneal epithelium is frequently exposed to injuries because it is located on the outer surface of the eye, which can result in severe visual impairment [3][62][63]. Moreover, damage and/or activation of corneal nerves—which are distributed on the epithelial surface—result in the release of large amounts of SP. Substance P can then bind to the NK1R abundantly expressed on the corneal epithelium and nerves [3][64][65].

The role of NK1R and its ligand SP in the maintenance of an intact corneal epithelium is epitomized by diabetic keratopathy, a form of neurotrophic keratopathy associated to sensory neuropathy and epithelial instability and/or disruption. SP levels are reduced in patients with type 1 diabetes, although it is not clear if this is simply a reflection of reduced corneal nerve density, which is commonly observed in these subjects [66][67][68].

5.2. NK1R and Ocular Inflammation

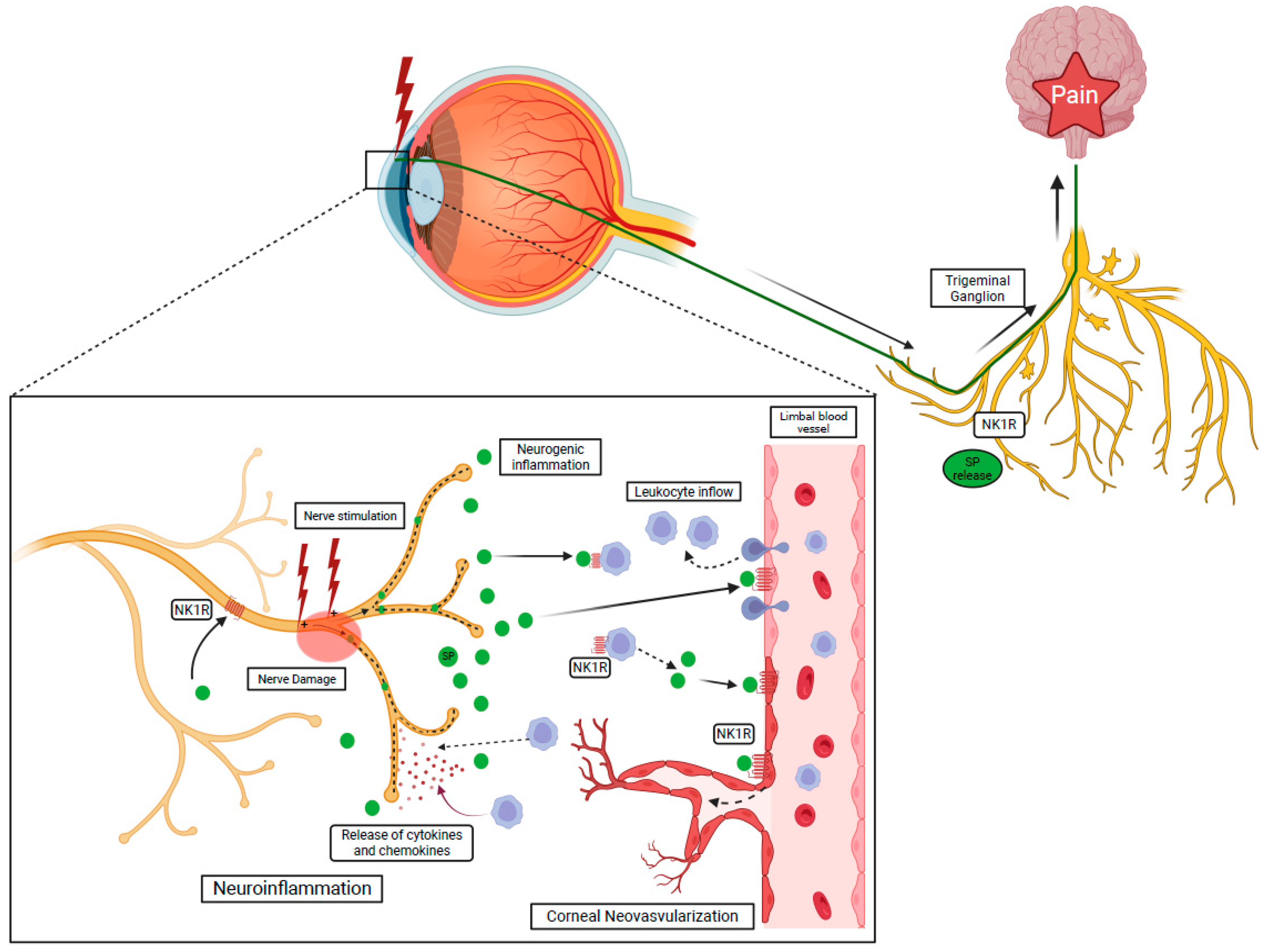

Activation of NK1R has a cardinal role in the modulation on multiple layers of the inflammatory response. In the cornea, the inflammatory response can be initiated by the release of the principal NK1R ligand, SP, following damage and/or stimulation of corneal nerves (neurogenic inflammation) (Figure 3) [3][62][69][70][71]. The NK1R is expressed by virtually all the key players of the inflammatory response: vascular endothelial cells, leukocytes, and nerves. Specifically, proliferation and migration of lymphatic endothelial cells are achieved through regulation of the VEGFR3 expression following SP-mediated NK1R activation and facilitated by the recruitment of neutrophils with angiogenic activity [51][72][73][74].

Figure 3. NK1R activation via SP induces the recruitment of the leukocyte through the breakdown of the blood–tissue barrier and initiates neurogenic inflammation. Activated leukocytes release cytokines and chemokines leading to nerve damage, called neuroinflammation.

The role of NK1R has also been studied in other retinal diseases. Proliferative vitreoretinopathy (PVR) is a serious complication of retinal detachment and is characterized by the growth and contraction of subretinal membranes within the vitreous cavity, ultimately leading to visual loss [75][76]. While the exact pathophysiology of PVR is still incompletely understood, it seems clear that an altered inflammatory response is involved. Interestingly, SP levels are increased in the ocular fluids of PVR patients. On the other hand, a study on mice showed that SP can inhibit the progression of PVR through modulation of cytokines including TNF-α [77][78]. In conclusion, existing evidence suggest that the exact roles of SP and its receptor NK1 in PVR needs further elucidation.

Herpes Simplex Keratitis (HSK) is associated with increased levels of SP in severe cases [79]. It was reported that CD8 T cell proliferation was significantly reduced in mice treated with an NK1R antagonist, L-760735, compared to controls, suggesting a key role for SP in herpes-induced corneal inflammation. In conclusion, blocking of SP suppresses the inflammation and infiltrating of immune cells [17][80][81].

5.3. NK1R and Ocular Pain

The activation of the NK1R is known to simultaneously promote inflammation and pain [3]. Corneal pain is normally generated by the activation of transient receptor potential. Trigeminal neurons are responsible for collection of sensory stimuli reaching the cornea and transmit them to the pons via their central branch. From there, the sensory information is further transmitted to the thalamus and cortex, through central neurons [82][83].

Ocular surface pain is a consequence of most ocular surface diseases, injuries, and surgery [84]. SP, acting through the NK1R, is involved in conveying corneal pain to the trigeminal ganglion. Specifically, it was shown that large amounts of SP are released in the tear fluid following nerve injury/stimulation [82][85]. SP can bind to the NK1R expressed on corneal nerves, therefore inducing nerve depolarization and pain [3][86]. Recently, it was demonstrated that topical application of an NK1R antagonist, fosaprepitant, resulted in a substantial decrease of corneal pain and leukocyte infiltration as a consequence of nerve-released SP blockade [87].

6. NK1R Antagonists and Their Potential in Eye Diseases

Different NK1R antagonists, including Fosaprepitant, Lanepitant, Spantide I/II, L-732138 and SR140333, L-733060, and aprepitant have been shown to be effective in ocular graft versus host diseases and pre-clinical models of eye diseases [60][62][88]. One of these medications, Fosaprepitant, has been in clinical use for years, with an excellent safety profile, for the treatment of nausea associated with chemotherapy. Fosaprepitant, applied topically to the ocular surface, effectively reduced ocular surface pain, hem- and lymphangiogenesis, and decreased the level of SP in the tear fluid [71][89]. Spantide I inhibited the synthesis of IL-8 in corneal epithelial cells, reduced infiltration of inflammatory cells, and decreased hemangiogenesis [90][91]. Spantide II was able to reinstate the previously abolished immune privilege in the cornea and allowed long-term survival of corneal grafts [92]. CP-96,345 reduced the SP-mRNA expression and inhibited IL-8 gene expression [93].

References

- Pennefather, J.N.; Lecci, A.; Candenas, M.L.; Patak, E.; Pinto, F.M.; Maggi, C.A. Tachykinins and Tachykinin Receptors: A Growing Family. Life Sci. 2004, 74, 1445–1463.

- Zhang, Y.; Berger, A.; Milne, C.D.; Paige, C.J. Tachykinins in the Immune System. Curr. Drug Targets 2006, 7, 1011–1020.

- Lasagni Vitar, R.M.; Rama, P.; Ferrari, G. The Two-Faced Effects of Nerves and Neuropeptides in Corneal Diseases. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2022, 86, 100974.

- Pinto, F.M.; Pintado, C.O.; Pennefather, J.N.; Patak, E.; Candenas, L. Ovarian Steroids Regulate Tachykinin and Tachykinin Receptor Gene Expression in the Mouse Uterus. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2009, 7, 77.

- Gerard, N.P.; Garraway, L.A.; Eddy, R.L.; Shows, T.B.; Iijima, H.; Paquet, J.L.; Gerard, C. Human Substance P Receptor (NK-1): Organization of the Gene, Chromosome Localization, and Functional Expression of CDNA Clones. Biochemistry 1991, 30, 10640–10646.

- Blasco, V.; Pinto, F.M.; González-Ravina, C.; Santamaría-López, E.; Candenas, L.; Fernández-Sánchez, M. Tachykinins and Kisspeptins in the Regulation of Human Male Fertility. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 9, 113.

- Keringer, P.; Rumbus, Z. The Interaction between Neurokinin-1 Receptors and Cyclooxygenase-2 in Fever Genesis. Temp. Austin 2019, 6, 4–6.

- Almeida, T.A.; Rojo, J.; Nieto, P.M.; Pinto, F.M.; Hernandez, M.; Martín, J.D.; Candenas, M.L. Tachykinins and Tachykinin Receptors: Structure and Activity Relationships. Curr. Med. Chem. 2004, 11, 2045–2081.

- Douglas, S.D.; Leeman, S.E. Neurokinin-1 Receptor: Functional Significance in the Immune System in Reference to Selected Infections and Inflammation. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2011, 1217, 83–95.

- Maggi, C.A. The Mammalian Tachykinin Receptors. Gen. Pharmacol. Vasc. Syst. 1995, 26, 911–944.

- Spitsin, S.; Pappa, V.; Douglas, S.D. Truncation of Neurokinin-1 Receptor-Negative Regulation of Substance P Signaling. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2018, 103, 1043–1051.

- Eapen, P.M.; Rao, C.M.; Nampoothiri, M. Crosstalk between Neurokinin Receptor Signaling and Neuroinflammation in Neurological Disorders. Rev. Neurosci. 2019, 30, 233–243.

- Lai, J.-P.; Lai, S.; Tuluc, F.; Tansky, M.F.; Kilpatrick, L.E.; Leeman, S.E.; Douglas, S.D. Differences in the Length of the Carboxyl Terminus Mediate Functional Properties of Neurokinin-1 Receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 12605–12610.

- Markovic, D.; Challiss, R.A.J. Alternative Splicing of G Protein-Coupled Receptors: Physiology and Pathophysiology. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2009, 66, 3337–3352.

- Tansky, M.F.; Pothoulakis, C.; Leeman, S.E. Functional Consequences of Alteration of N-Linked Glycosylation Sites on the Neurokinin 1 Receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 10691–10696.

- Redkiewicz, P. The Regenerative Potential of Substance P. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 750.

- Singh, R.B.; Naderi, A.; Cho, W.; Ortiz, G.; Musayeva, A.; Dohlman, T.H.; Chen, Y.; Ferrari, G.; Dana, R. Modulating the Tachykinin: Role of Substance P and Neurokinin Receptor Expression in Ocular Surface Disorders. Ocul. Surf. 2022, 25, 142–153.

- Bignami, F.; Rama, P.; Ferrari, G. Substance P and Its Inhibition in Ocular Inflammation. Curr. Drug Targets 2016, 17, 1265–1274.

- Maggi, C.A.; Patacchini, R.; Giachetti, A.; Meli, A. Tachykinin Receptors in the Circular Muscle of the Guinea-Pig Ileum. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1990, 101, 996–1000.

- Satake, H.; Kawada, T. Overview of the Primary Structure, Tissue-Distribution, and Functions of Tachykinins and Their Receptors. Curr. Drug Targets 2006, 7, 963–974.

- Bost, K.L. Tachykinin-Mediated Modulation of the Immune Response. Front. Biosci. 2004, 9, 3331–3332.

- Koon, H.-W.; Zhao, D.; Na, X.; Moyer, M.P.; Pothoulakis, C. Metalloproteinases and Transforming Growth Factor-α Mediate Substance P-Induced Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Activation and Proliferation in Human Colonocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 45519–45527.

- Garcia-Hirschfeld, J.; Lopez-Briones, L.G.; Belmonte, C. Neurotrophic Influences on Corneal Epithelial Cells. Exp. Eye Res. 1994, 59, 597–605.

- Słoniecka, M.; Le Roux, S.; Zhou, Q.; Danielson, P. Substance P Enhances Keratocyte Migration and Neutrophil Recruitment through Interleukin-8. Mol. Pharmacol. 2016, 89, 215–225.

- Morelli, A.E.; Sumpter, T.L.; Rojas-Canales, D.M.; Bandyopadhyay, M.; Chen, Z.; Tkacheva, O.; Shufesky, W.J.; Wallace, C.T.; Watkins, S.C.; Berger, A.; et al. Neurokinin-1 Receptor Signaling Is Required for Efficient Ca2+ Flux in T-Cell-Receptor-Activated T Cells. Cell Rep. 2020, 30, 3448–3465.e8.

- García-Aranda, M.; Téllez, T.; McKenna, L.; Redondo, M. Neurokinin-1 Receptor (NK-1R) Antagonists as a New Strategy to Overcome Cancer Resistance. Cancers 2022, 14, 2255.

- O’Hayre, M.; Degese, M.S.; Gutkind, J.S. Novel Insights into G Protein and G Protein-Coupled Receptor Signaling in Cancer. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2014, 27, 126–135.

- Morishita, R.; Ueda, H.; Ito, H.; Takasaki, J.; Nagata, K.-I.; Asano, T. Involvement of Gq/11 in Both Integrin Signal-Dependent and -Independent Pathways Regulating Endothelin-Induced Neural Progenitor Proliferation. Neurosci. Res. 2007, 59, 205–214.

- Guard, S.; Watson, S.P. Tachykinin Receptor Types: Classification and Membrane Signalling Mechanisms. Neurochem. Int. 1991, 18, 149–165.

- Ye, R.D. Regulation of Nuclear Factor KappaB Activation by G-Protein-Coupled Receptors. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2001, 70, 839–848.

- Tsybko, A.S.; Ilchibaeva, T.V.; Popova, N.K. Role of Glial Cell Line-Derived Neurotrophic Factor in the Pathogenesis and Treatment of Mood Disorders. Rev. Neurosci. 2017, 28, 219–233.

- Schwindinger, W.F.; Robishaw, J.D. Heterotrimeric G-Protein Βγ-Dimers in Growth and Differentiation. Oncogene 2001, 20, 1653–1660.

- Raddatz, R.; Crankshaw, C.L.; Snider, R.M.; Krause, J.E. Similar Rates of Phosphatidylinositol Hydrolysis Following Activation of Wild-Type and Truncated Rat Neurokinin-1 Receptors. J. Neurochem. 2002, 64, 1183–1191.

- Torrens, Y.; Daguet De Montety, M.C.; el Etr, M.; Beaujouan, J.C.; Glowinski, J. Tachykinin Receptors of the NK1 Type (Substance P) Coupled Positively to Phospholipase C on Cortical Astrocytes from the Newborn Mouse in Primary Culture. J. Neurochem. 1989, 52, 1913–1918.

- Sun, L.; Yu, F.; Ullah, A.; Hubrack, S.; Daalis, A.; Jung, P.; Machaca, K. Endoplasmic Reticulum Remodeling Tunes IP3-Dependent Ca2+ Release Sensitivity. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e27928.

- Meshki, J.; Douglas, S.D.; Lai, J.-P.; Schwartz, L.; Kilpatrick, L.E.; Tuluc, F. Neurokinin 1 Receptor Mediates Membrane Blebbing in HEK293 Cells through a Rho/Rho-Associated Coiled-Coil Kinase-Dependent Mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 9280–9289.

- Kelly, P.; Moeller, B.J.; Juneja, J.; Booden, M.A.; Der, C.J.; Daaka, Y.; Dewhirst, M.W.; Fields, T.A.; Casey, P.J. The G12 Family of Heterotrimeric G Proteins Promotes Breast Cancer Invasion and Metastasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 8173–8178.

- Kelly, P.; Stemmle, L.N.; Madden, J.F.; Fields, T.A.; Daaka, Y.; Casey, P.J. A Role for the G12 Family of Heterotrimeric G Proteins in Prostate Cancer Invasion. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 26483–26490.

- Garcia-Recio, S.; Gascón, P. Biological and Pharmacological Aspects of the NK1-Receptor. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 495704.

- Yamaguchi, K.; Kugimiya, T.; Miyazaki, T. Substance P Receptor in U373 MG Human Astrocytoma Cells Activates Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases ERK1/2 through Src. Brain Tumor Pathol. 2005, 22, 1–8.

- Wong, Y.H.; Federman, A.; Pace, A.M.; Zachary, I.; Evans, T.; Pouysségur, J.; Bourne, H.R. Mutant Alpha Subunits of Gi2 Inhibit Cyclic AMP Accumulation. Nature 1991, 351, 63–65.

- Ma, Y.C.; Huang, J.; Ali, S.; Lowry, W.; Huang, X.Y. Src Tyrosine Kinase Is a Novel Direct Effector of G Proteins. Cell 2000, 102, 635–646.

- Ding, H.; Zhang, X.; Su, Y.; Jia, C.; Dai, C. GNAS Promotes Inflammation-Related Hepatocellular Carcinoma Progression by Promoting STAT3 Activation. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 2020, 25, 8.

- Johnson, E.N.; Druey, K.M. Heterotrimeric G Protein Signaling: Role in Asthma and Allergic Inflammation. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2002, 109, 592–602.

- He, X.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Y.; Remke, M.; Shih, D.; Lu, F.; Wang, H.; Deng, Y.; Yu, Y.; Xia, Y.; et al. The G Protein α Subunit Gαs Is a Tumor Suppressor in Sonic Hedgehog-Driven Medulloblastoma. Nat. Med. 2014, 20, 1035–1042.

- Yan, L.; Herrmann, V.; Hofer, J.K.; Insel, P.A. Beta-Adrenergic Receptor/CAMP-Mediated Signaling and Apoptosis of S49 Lymphoma Cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2000, 279, C1665–C1674.

- Bonelli, F.; Lasagni Vitar, R.M.; Merlo Pich, F.G.; Fonteyne, P.; Rama, P.; Mondino, A.; Ferrari, G. Corneal Endothelial Cell Reduction and Increased Neurokinin-1 Receptor Expression in a Graft-versus-Host Disease Preclinical Model. Exp. Eye Res. 2022, 220, 109128.

- Roux, S.L.; Borbely, G.; Słoniecka, M.; Backman, L.J.; Danielson, P. Transforming Growth Factor Beta 1 Modulates the Functional Expression of the Neurokinin-1 Receptor in Human Keratocytes. Curr. Eye Res. 2016, 41, 1035–1043.

- Gaddipati, S.; Rao, P.; Jerome, A.D.; Burugula, B.B.; Gerard, N.P.; Suvas, S. Loss of Neurokinin-1 Receptor Alters Ocular Surface Homeostasis and Promotes an Early Development of Herpes Stromal Keratitis. J. Immunol. 2016, 197, 4021–4033.

- Edvinsson, J.C.; Reducha, P.V.; Sheykhzade, M.; Warfvinge, K.; Haanes, K.A.; Edvinsson, L. Neurokinins and Their Receptors in the Rat Trigeminal System: Differential Localization and Release with Implications for Migraine Pain. Mol. Pain 2021, 17, 17448069211059400.

- Lee, S.J.; Im, S.-T.; Wu, J.; Cho, C.S.; Jo, D.H.; Chen, Y.; Dana, R.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, S.-M. Corneal Lymphangiogenesis in Dry Eye Disease Is Regulated by Substance P/Neurokinin-1 Receptor System through Controlling Expression of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor 3. Ocul. Surf. 2021, 22, 72–79.

- Lasagni Vitar, R.M.; Bonelli, F.; Atay, A.; Triani, F.; Fonteyne, P.; Di Simone, E.; Rama, P.; Mondino, A.; Ferrari, G. Topical Neurokinin-1 Receptor Antagonist Fosaprepitant Ameliorates Ocular Graft-versus-Host Disease in a Preclinical Mouse Model. Exp. Eye Res. 2021, 212, 108825.

- Yamada, M.; Ogata, M.; Kawai, M.; Mashima, Y.; Nishida, T. Substance P in Human Tears. Cornea 2003, 22, S48–S54.

- Yamada, M.; Ogata, M.; Kawai, M.; Mashima, Y.; Nishida, T. Substance P and Its Metabolites in Normal Human Tears. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2002, 43, 2622–2625.

- Suvas, S. Role of Substance P Neuropeptide in Inflammation, Wound Healing, and Tissue Homeostasis. J. Immunol. 2017, 199, 1543–1552.

- Mishra, A.; Lal, G. Neurokinin Receptors and Their Implications in Various Autoimmune Diseases. Curr. Res. Immunol. 2021, 2, 66–78.

- Kitamura, H.; Kobayashi, M.; Wakita, D.; Nishimura, T. Neuropeptide Signaling Activates Dendritic Cell-Mediated Type 1 Immune Responses through Neurokinin-2 Receptor. J. Immunol. Baltim. Md. 1950 2012, 188, 4200–4208.

- Hall, J.M.; Mitchell, D.; Morton, I.K.M. Typical and Atypical NK1 Tachykinin Receptor Characteristics in the Rabbit Isolated Iris Sphincter. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1994, 112, 985–991.

- Hwang, D.D.-J.; Lee, S.-J.; Kim, J.-H.; Lee, S.-M. The Role of Neuropeptides in Pathogenesis of Dry Dye. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 4248.

- Yu, M.; Lee, S.-M.; Lee, H.; Amouzegar, A.; Nakao, T.; Chen, Y.; Dana, R. Neurokinin-1 Receptor Antagonism Ameliorates Dry Eye Disease by Inhibiting Antigen-Presenting Cell Maturation and T Helper 17 Cell Activation. Am. J. Pathol. 2020, 190, 125–133.

- Liu, L.; Dana, R.; Yin, J. Sensory Neurons Directly Promote Angiogenesis in Response to Inflammation via Substance P Signaling. FASEB J. Off. Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 2020, 34, 6229–6243.

- Bignami, F.; Giacomini, C.; Lorusso, A.; Aramini, A.; Rama, P.; Ferrari, G. NK1 Receptor Antagonists as a New Treatment for Corneal Neovascularization. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2014, 55, 6783–6794.

- Ljubimov, A.V.; Saghizadeh, M. Progress in Corneal Wound Healing. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2015, 49, 17–45.

- Labetoulle, M.; Baudouin, C.; Calonge, M.; Merayo-Lloves, J.; Boboridis, K.G.; Akova, Y.A.; Aragona, P.; Geerling, G.; Messmer, E.M.; Benítez-del-Castillo, J. Role of Corneal Nerves in Ocular Surface Homeostasis and Disease. Acta Ophthalmol. 2019, 97, 137–145.

- Zoukhri, D. Effect of Inflammation on Lacrimal Gland Function. Exp. Eye Res. 2006, 82, 885–898.

- Mansoor, H.; Tan, H.C.; Lin, M.T.-Y.; Mehta, J.S.; Liu, Y.-C. Diabetic Corneal Neuropathy. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3956.

- Zhou, T.; Lee, A.; Lo, A.C.Y.; Kwok, J.S.W.J. Diabetic Corneal Neuropathy: Pathogenic Mechanisms and Therapeutic Strategies. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 816062.

- Dogru, M.; Katakami, C.; Inoue, M. Tear Function and Ocular Surface Changes in Noninsulin-Dependent Diabetes Mellitus. Ophthalmology 2001, 108, 586–592.

- Choi, J.E.; Di Nardo, A. Skin Neurogenic Inflammation. Semin. Immunopathol. 2018, 40, 249–259.

- Corrigan, F.; Vink, R.; Turner, R.J. Inflammation in Acute CNS Injury: A Focus on the Role of Substance P: Neurogenic Inflammation in Acute CNS Injury. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2016, 173, 703–715.

- Barbariga, M.; Fonteyne, P.; Ostadreza, M.; Bignami, F.; Rama, P.; Ferrari, G. Substance P Modulation of Human and Murine Corneal Neovascularization. Investig. Opthalmology Vis. Sci. 2018, 59, 1305–1312.

- Ziche, M.; Morbidelli, L.; Pacini, M.; Geppetti, P.; Alessandri, G.; Maggi, C.A. Substance P Stimulates Neovascularization in Vivo and Proliferation of Cultured Endothelial Cells. Microvasc. Res. 1990, 40, 264–278.

- Greeno, E.W.; Mantyh, P.; Vercellotti, G.M.; Moldow, C.F. Functional Neurokinin 1 Receptors for Substance P Are Expressed by Human Vascular Endothelium. J. Exp. Med. 1993, 177, 1269–1276.

- Kohara, H.; Tajima, S.; Yamamoto, M.; Tabata, Y. Angiogenesis Induced by Controlled Release of Neuropeptide Substance P. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 8617–8625.

- Troger, J.; Kremser, B.; Irschick, E.; Göttinger, W.; Kieselbach, G. Substance P in Proliferative Vitreoretinopathy: The Significance of Aqueous Humor Levels for Evolution of the Disease. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 1998, 236, 900–903.

- Nagasaki, H.; Shinagawa, K.; Mochizuki, M. Risk Factors for Proliferative Vitreoretinopathy. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 1998, 17, 77–98.

- Yoo, K.; Son, B.K.; Kim, S.; Son, Y.; Yu, S.-Y.; Hong, H.S. Substance P Prevents Development of Proliferative Vitreoretinopathy in Mice by Modulating TNF-α. Mol. Vis. 2017, 23, 933–943.

- Idrees, S.; Sridhar, J.; Kuriyan, A.E. Proliferative Vitreoretinopathy: A Review. Int. Ophthalmol. Clin. 2019, 59, 221–240.

- Bagga, B.; Kate, A.; Joseph, J.; Dave, V.P. Herpes Simplex Infection of the Eye: An Introduction. Community Eye Health 2020, 33, 68–70.

- Jerome, A.; Suvas, S. Discrepancy between Neurokinin 1 Receptor Antagonist Treatment and Neurokinin 1 Receptor Knockout Mice in the CD8 T Cell Response to Corneal HSV-1 Infection. J. Immunol. 2018, 200, 126.16.

- Poccardi, N.; Rousseau, A.; Haigh, O.; Takissian, J.; Naas, T.; Deback, C.; Trouillaud, L.; Issa, M.; Roubille, S.; Juillard, F.; et al. Herpes Simplex Virus 1 Replication, Ocular Disease, and Reactivations from Latency Are Restricted Unilaterally after Inoculation of Virus into the Lip. J. Virol. 2019, 93, e01586-19.

- McKay, T.B.; Seyed-Razavi, Y.; Ghezzi, C.E.; Dieckmann, G.; Nieland, T.J.F.; Cairns, D.M.; Pollard, R.E.; Hamrah, P.; Kaplan, D.L. Corneal Pain and Experimental Model Development. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2019, 71, 88–113.

- Puja, G.; Sonkodi, B.; Bardoni, R. Mechanisms of Peripheral and Central Pain Sensitization: Focus on Ocular Pain. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 764396.

- Mehra, D.; Cohen, N.K.; Galor, A. Ocular Surface Pain: A Narrative Review. Ophthalmol. Ther. 2020, 9, 1–21.

- Hagan, S.; Martin, E.; Enríquez-de-Salamanca, A. Tear Fluid Biomarkers in Ocular and Systemic Disease: Potential Use for Predictive, Preventive and Personalised Medicine. EPMA J. 2016, 7, 15.

- Galor, A.; Hamrah, P.; Haque, S.; Attal, N.; Labetoulle, M. Understanding Chronic Ocular Surface Pain: An Unmet Need for Targeted Drug Therapy. Ocul. Surf. 2022, 26, 148–156.

- Lasagni Vitar, R.M.; Barbariga, M.; Fonteyne, P.; Bignami, F.; Rama, P.; Ferrari, G. Modulating Ocular Surface Pain Through Neurokinin-1 Receptor Blockade. Investig. Opthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2021, 62, 26.

- Puri, S.; Kenyon, B.M.; Hamrah, P. Immunomodulatory Role of Neuropeptides in the Cornea. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1985.

- Bignami, F.; Lorusso, A.; Rama, P.; Ferrari, G. Growth Inhibition of Formed Corneal Neovascularization Following Fosaprepitant Treatment. Acta Ophthalmol. 2017, 95, e641–e648.

- Tran, M.T.; Lausch, R.N.; Oakes, J.E. Substance P Differentially Stimulates IL-8 Synthesis in Human Corneal Epithelial Cells. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2000, 41, 3871–3877.

- Johnson, M.B.; Young, A.D.; Marriott, I. The Therapeutic Potential of Targeting Substance P/NK-1R Interactions in Inflammatory CNS Disorders. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2017, 10, 296.

- Paunicka, K.J.; Mellon, J.; Robertson, D.; Petroll, M.; Brown, J.R.; Niederkorn, J.Y. Severing Corneal Nerves in One Eye Induces Sympathetic Loss of Immune Privilege and Promotes Rejection of Future Corneal Allografts Placed in Either Eye: Corneal Nerves and Corneal Graft Rejection. Am. J. Transplant. 2015, 15, 1490–1501.

- Lai, J.-P.; Ho, W.-Z.; Yang, J.-H.; Wang, X.; Song, L.; Douglas, S.D. A Non-Peptide Substance P Antagonist down-Regulates SP MRNA Expression in Human Mononuclear Phagocytes. J. Neuroimmunol. 2002, 128, 101–108.

More

Information

Subjects:

Neurosciences

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.4K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

30 Nov 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No