| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Annie Tubadji | + 3222 word(s) | 3222 | 2020-11-20 07:11:06 | | | |

| 2 | Catherine Yang | Meta information modification | 3222 | 2020-12-21 08:04:59 | | |

Video Upload Options

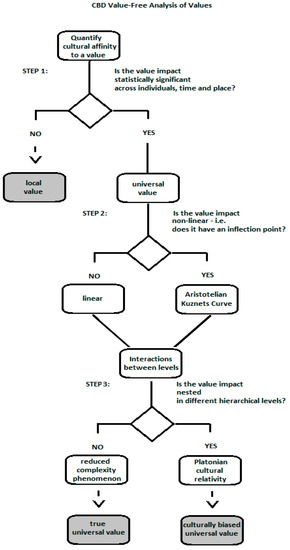

The Culture-Based Development (CBD) approach suggests that the value-free analysis of values needs: (i) to use positive methods to classify a value as local or universal; (ii) to examine the existence of what is termed the Aristotelian Kuznets curve of values (i.e., to test for the presence of an inflection point in the economic impact from the particular value) and (iii) to account for Platonian cultural relativity (i.e., the cultural embeddedness expressed in the geographic nestedness of the empirical data about values). In short, the value-free analysis of values is a novel methodological protocol that ensures an accurate and precise analysis of the impact from a particular cultural value on a specific socio-economic outcome of interest.

1. Introduction

Can economics identify which local cultural attitudes are universally valuable for the economic systems? A system that depends on value judgements cannot be adequately studied without including values as a factor for the operation of the system. Yet, a scientific study of values should be objective, without deterministic subjective labelling of values as good or bad. The Culture-Based Development (CBD) approach proposes that the universality of a value should be positively analyzed against its objective effect on a socio-economic output of interest.

The question about the importance of values for the existence of economies and society has been an integral part of science since its very dawn. Based on: (i) a systematic literature review covering contributions from 1677 till 2020 on economic thought on values, culture, wellbeing and welfare and earlier philosophical contributions that this economic research built on (reviewing material mainly from Jstor, Web of Science, Google Scholar and Science Direct); and then (ii) an integrative literature review that synthesizes and recombines main perspectives from part one, in order to create a new theoretical model (of value free analysis of values), CBD delivers a mixed method of systematic-integrative literature review and outlines several cornerstones in the literature of particular importance to economics as a field and fundamental for the here proposed specific CBD approach for the value-free analysis of values (see the link to the full article at the end of this entry).

Modern moral philosophy, propelled by Sen and Nussbaum’s research, calls for a return to the question of values in studying the factors for economic development [1][2][3][4][5][6][7]. Revisiting the argonauts of philosophy and sciences, Plato, and his student Aristotle, we choose to highlight here two main concepts, which are very compatible with each other. Plato (Republic 375 BC) is known for his parable of the cave, suggesting that cultural relativity of values exists due to the individual’s local bias in the perception of the pure truth. Pure truth is presented by the parable as a flame and one’s perception of pure truth is equivalent to only the reflection of this flame on the walls of one’s own ‘cave’ (i.e., one’s context). Aristotle (Nicomachean Ethics 350 BCE) suggested that a ‘golden mean’ of every value exists. Put differently, too much or too little affinity towards a particular value never leads to the most optimal behavior. Instead, an individual needs to empirically find out where the most-useful (i.e., ‘golden’) mean level of affinity to a value should be placed in order to live a really good life. Next, the father of economics as a moral philosophy, Adam Smith [8], suggested his own theory of moral sentiments, relying to a big extent on the notion of the ‘Impartial’ Spectator. In line with work by Khalil [9], the latter notion is interpreted in this study as the presence of a socially prescribed and internally monitored value system, which is in essence the outline of the cultural cave in which we are embedded. These three classical approaches to studying values have been deserted in neoclassical economics for decades.

In the 1930s, the urge for a value-free study of economics was suggested by neoclassical economists [10][11]. It was argued that utility and culture are difficult to measure and explain. It was hoped that a study of the economy as a system, operating on certain value-free mechanisms, could help reveal these mechanisms and put them in service for socio-economic recovery and development [12]. It was however, soon realized that it is impossible to mechanically separate culture from the economic mechanisms. Signals for this problem started being powerfully sent by important contributions to the new economic academic world [13][14]. The work by Herbert Simon, Tibor Scitovsky, Daniel Kahneman has pointed to the cultural- and value-dependence of the macro economics of place development and micro economics of customer behavior [15][16][17]. Yet, the cultural economics field became too diverse and internally disintegrated, and remained mostly apocrypha and muted in the majority of its contributions, ultimately evolving into a misperception that there needs to be necessarily some deep methodological divide between neoclassical and institutional (cultural) economics.

It was only in recent years that New Institutional Economics (NIE) realized and started promoting the alternative more natural thesis—that actually using a common methodological ground might be the key to ameliorating the general economic field and its understanding of culture and values.

New Institutional Economics (NIE) revolutionalized the field of institutional economics by opening its doors in a pluralistic manner to the use of empirical methods. NIE promoted the quantitative study of institutions and culture [18]. Studies building on this literature have empirically demonstrated that there is persistence and path-dependence in the process of impact by cultural institutions on socio-economic development [19]. Working on a very similar vein, one of the fathers of modern Political Economy, Alesina and Perotti [20], demonstrate how empirical neoclassical models can accommodate for the study of the impact by political and voting behavior on the economic process. The entire field of New Cultural Economics (NCE) has also generated numerous elaborate empirical studies demonstrating the various effects of cultural variables on various economic processes [21][22]. Alesina, Miano and Stancheva [23] also discuss the endogeneity of values and beliefs.

CBD is a research paradigm which defines development as a process that depends on economic decisions which are inevitably culturally embedded and biased. In this study, CBD suggests a systematic approach to value-free study of any value in three steps through: (i) establishing whether the value has a universal impact across space, (ii) detecting if its impact exhibits nonlinearities (such as Aristotle’s golden mean suggests) and (iii) explaining through Platonian cultural relativity how the universality of moral values and the presence of diverse local culturally dependent ethics can find a coherent conceptual and empirical explanation.

2. Main Principles of the CBD Value-Free Analysis of Values

Ultimately, CBD seeks to analyze the objective effect of an attitude on the output without implying any qualitative judgement whether this is a good or a bad (virtuous or not virtuous) outcome i.e., in a value-free manner. Moreover, CBD aims to offer a roadmap for answering both the first Adam Smith’s question about moral philosophy (whether a value is universally virtuous), and also his second question, regarding the systematic internal mechanisms and complexities of this impact. CBD does so through a positive methodology and with a different rationale than what has been done so far.

Addressing the first question, the CBD value-free study of values leads us to first objectively identify whether a value/attitude is universally-contributive to certain outcomes of interest, without involving subjective pre-determined classifications or prescriptions of what should be thought as ‘virtuous’. Here, the CBD approach suggests focusing the analysis on a positive exploration of what are the objective observed consequences of certain values.

Addressing the second question, the CBD approach suggests accounting for the complexity of culture and the non-linearity of its impact [24] CBD classifies a value’s universality based on positively documented trans-geographical and trans-cultural impact of this value on certain outcomes of interest. CBD distinguishes between a true universal/moral value and a culturally biased universal value. The distinction between the two types of universal values is based on the objective universality of the impact from the value with regards to the same outcome across space as opposed to presence of local cultural bias (expressed in heterogeneity of the impact across space). Put differently, the CBD addresses the second question by finding out in a positive manner whether a certain value behaves as: (i) part of a truly universal ‘Impartial’ Spectator (of Adam Smith’s original type); or (ii) a value that has (a) a varying significance across time and space and also (b) only a partial, in terms of weak, Culturally Biased Spectator (i.e., ultimately boundedly partial ‘Impartial’ Spectators (due to doxa, as defined in the previous section)). Thus, the CBD proposed approach of value-free analysis of values entails a procedure composed of three clear cut methodological steps, as detailed below.

2.1. When Is a Value Universal?

CBD proposes the positive study of values to start with the clear acknowledgement of the Cartesian doubt, i.e., the limitation of the mind in knowing the absolute truth even based on induction. CBD recognizes that the natural moral cannot be readily known by human deduction or induction, and yet, CBD proposes a positive study of values, aiming to understand: (i) whether they are potentially of universal benefit with regard to particular outcome of interest and (ii) if so-how much deviation (cultural bias) exists locally with regards to these universal values in the current world. Put differently, CBD proposes to study positively the universality of the impact from values through empirical methods regarding particular outcomes. This positive approach purges the value judgementalism in the analysis of values by basing the classification on observed outcomes.

Namely, the first step of the proposed CBD approach to value-free analysis of values is consistent as method with what is done so far in quantitative studies in cultural economics, but the CBD interpretation of the results is from a different perspective. It still entails identifying a measure or proxy for a certain cultural value that varies across individuals or places, and then testing whether this value-related variable exhibits statistical significance for the outcome of interest [21][22]. However, it judges the universal ‘virtuousness’ of the value based on the statistical significance it can exhibit. Clearly, this testing requires precise model and quantitative method, implemented at the presence of individual and space related fixed effects and relevant controls and other explanatory variables that fully specify the model.

The above first step of the CBD approach is in line with Adam Smith’s suggestion that universal values are a natural global tendency of all ‘Impartial’ Spectators’, who indifferent of their subjective and culturally relative bias are generally converging towards a common natural tendency worldwide (see Glick [25] on cultural relativity and differences between culture and morality from anthropological perspective and Littlewood [26] for an extensive literature review on the matter). Smith’s claim that a worldwide predominant value is universal however is treated by CBD as in essence a deterministic claim. Instead, CBD first positively tests whether the affinity to the value produces the desired outcome of interest and only then classifies this value as universal. Thus, it is not the presence of affinity but the outcome of this affinity that CBD uses to define the universality of the value in a value-free manner.

2.2. Aristotelian Kuznets Curve

Aristotle’s and Plato’s view on values are sometimes considered as opposing since Aristotle’s view suggests that some middle enacted level of an attitude is best (virtuous), while Plato generally suggests that nothing practiced is as good as the real true best (virtue) [27]. Yet, CBD interprets these two stands as simply alternative aspects of virtue. Aristotle’s take regards the amount of affinity (passion) and its eventual turning point above which the effect of the value of the outcome changes sign after a certain increase in amount of affinity to this value. Plato’s take on virtue, instead, is embraced by CBD from the perspective of its meaning for regional cultural relativity, namely: the local natural moral can be seen as always deviating from the natural ideal mean due to local cultural biases and path-dependencies in culture.

Kuznets [28][29] demonstrated that the concentration of people in cities had first a positive, then a negative association with certain regional development aspects such as inequality. Similar relationship of urbanization with pollution was termed the environmental Kuznets curve [30][31]. CBD reinterprets this in Aristotelian golden mean sense, as the ‘goodness’ of the value to be in the city being first associated with a positive outcome, yet, with the increase in affinity to this value, an inflection point in the impact occurs, and its impact becomes positive (entailing many complex economic reasons for this switch of sign).

Therefore, CBD proposes that at a second step, after identifying the universality of a certain value, the analysis of its impact should go beyond asking whether an impact exists universally and should disentangle how exactly this impact is generated. Namely, CBD points to the importance of acknowledging the Aristotelian notion of the ‘golden mean’ of a value. Aristotle, whom Smith largely follows in his dwelling on virtue, suggests that a virtue is not an extreme but a well-measured optimally balanced point between two extremes of affinity to an attitude. For example, too much affinity to the attitude that good humour is important may result in a phoney clownish behavior, and too little affinity to this attitude may result into low spiritedness.

Thus, the positive approach proposed by CBD coins here the notion of Aristotelian Kuznets Curve which can be used to conduct the empirical analysis of the impact from a value in terms of the existence of an inflection point. Such an inflection point will document a non-linearity in the impact from this value (i.e., a form of Kuznets curve type of relationship between the increase in affinity to an attitude (how much virtuous a virtue is perceived) and its impact on the outcome of interest). This Kuznets curve relationship should be thought of in absolute terms as a nonlinearity of the impact at the presence of a linear increase in the input. Thus, the presence of an inflection point is interesting in itself, indifferent if it switches from positive to negative impact or vice versa. This is part of the value-free rationale proposed here by CBD.

If such an inflection point is found to exist, then Amartya Sen’s claim that freedom of capabilities is a universal value will be positively empirically confirmed. Namely, a Kuznets curve of this kind will signify that too much of any virtuous/‘good thing’ (too much of affinity to an universal value, may become, after a certain level of affinity, less conducive to the outcome of interest (i.a. there are prominent contributions to growth theory, showing that too much investment in R&D becomes negatively impacting the economic growth process [32]). Therefore, when the inflection point is reached, people should have the freedom to switch their order of preferences and opt out from further increases in their affinity to this value if they want to optimize the cultural value input and to maximize the outcome of interest.

Put differently, it is crucial that decision makers have the freedom to constantly update themselves on whether their level of affinity to a certain attitude is currently below, at or above the inflection point of the Aristotelian Kuznets curve and to change their order of preferences accordingly, so that their overall utility is indeed maximized through their choice. Yet, the existence of an Aristotelian Kuznets curve in the relationship between the amount of an affinity to a value and the amount of a certain outcome of interest is an empirical question.

2.3. Platonian Cultural Bias: Subjectivity and Relativity of the ‘Impartial’ Spectator

Adam Smith himself noted that the ‘Impartial’ Spectator is prone to individual subjectivity and cultural relativity biases due to customs and social proximity (TMS, Part I, Chapter I–V; Part V, Chapter I). CBD agrees with this, by understanding it from Plato’s point of view that the true moral is an unknown ideal state of calibration of the affinity to certain values (a view that has been pointed out also in related research [26][33]. Local ethics represent only ‘reflections from the flame’ of this ideal on the local ‘cave’ of a particular time and space. Thus, CBD states that local cultural capital creates local culturally biased ‘morals’ which have been transmitted across generations through the persistence of group ethics.

CBD therefore proposes as a third step the analysis of universal values to pass through the empirical cleaning of subjectivity and positive documentation of its geographic relativity. In particular, CBD suggests that the individual subjectivity of values can be treated as individual uniqueness (see Shackle [34]) and can be cured empirically through the use of individual fixed effects. CBD has also been flagging elsewhere (see for instance [35]) the danger of ‘throwing the baby with the water’, since an under-specification of an empirical model may result due to the omission of the cultural factor and simple use of individual fixed effects. Use of fixed effects without presence of cultural explanatory variables results in inability to analyze the cultural effect on individual choice. Here, however, we recommend use of individual fixed effects in the presence of cultural explanatory variables).

Meanwhile, the cultural relativity of values and moral systems can be understood and handled in the analysis as a local (ethical/cultural) bias over the ‘fellow-feeling’ which dictates the ‘Impartial’ Spectators ‘sentimental’ reasoning (for some recent contributions on the role of feelings/emotions in socio-economic behavior, see Borowecki [36] from an economic perspective, and Nussbaum [8] from a philosophical perspective). This bias is sometimes termed in the economic literature as ‘home bias’ [37][38][39]. This cultural relativity bias has in its roots the local cultural capital and it creates nestedness of the individual observations in local cultural groups. This nestedness has to be empirically modelled accordingly in order to cure the Platonian cultural bias from identifying the impact of a value. The use of hierarchical modelling or other related methods that stochastically account for both the individual and local effects in the data are suggested to cure the Platonian subjective and cultural relativity.

Figure 1 provides a synthesis of the above proposed three steps. It depicts the logic tree behind the three steps that the CBD value-free analysis of values suggests and sums up the main rationale for each step. Implementing the three steps of the CBD value-free analysis of values can help determine whether a value has a universal socio-economic significance; whether there is some limit to its exploitation (if there is an inflection point shaping an Aristotelian Kuznets curve); and whether it is subject to cultural biases that can make the transferability of interventions with regard to this value sensitive to the context in which they are implemented (pointing precisely analytically to what structural level drives the effect in the economic system).

Figure 1. The CBD Value-free Analysis of Values—Logic Tree Diagram. Note: The figure shows the essence of each logical step in the CBD value-free analysis of values, respectively: (i) Step 1—identifying whether a value is universal or local in terms of its impact; (ii) Step 2—identifying nonlinearities in the impact from the value, or the presence of what is called the Aristotelian Kuznets Curve; (iii) Step 3—exploring the complexities of the impact from the value in terms of the individual and local levels that shape the Platonian cultural relativity of values.

References

- Sen, A. Gender Inequality and Theories of Justice. In Women, Culture, and Development; Nussbaum, M.C., Glover, J., Eds.; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1995; pp. 259–273.

- Sen, A. On Ethics and Economics; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1987.

- Nussbaum, M.C. Philosophy and Economics in the Capabilities Approach: An Essential Dialogue. J. Hum. Dev. Capab. 2015, 16, 1–14.

- Nussbaum, M.C. Economics Still Needs Philosophy. Rev. Soc. Econ. 2016, 74, 229–247.

- Nussbaum, M.C. Morality and Emotions. Routledge Encycl. Philos. 2018.

- Nussbaum, M. Upheavals of Thought: The Intelligence of Emotions; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001.

- Nussbaum, M.; Sen, A. The Quality of Life; Calrendon Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993.

- Smith, A. The Theory of Moral Sentiments; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1759.

- Khalil, E.L. Adam Smith and Three Theories of Altruism. Rech. Econ. Louvain 2001, 67, 421–435.

- Robbins, L. An Essay on the Nature and Significance of Economic Science; Macmillan &, Co.: London, UK, 1932.

- Heilbroner, R.L. Economics as a “Value-Free” Science. Soc. Res. 1973, 40, 129–143.

- Putnam, H.; Walsh, V. The End of Value-Free Economics; Routledge: London, UK, 2012.

- Klappholz, K. Value Judgments and Economics. Br. J. Philos. Sci. 1964, 15, 97–114.

- Sinha, A. Theories of Value from Adam Smith to Piero Sraffa; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2018.

- Simon, H. A behavioral model of rational choice. Q. J. Econ. 1955, 69, 99–118.

- Scitovsky, T. The Joyless Economy; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1992.

- Kahneman, D. Thinking, Fast and Slow; Macmillan: London, UK, 2011.

- Adkisson, R.V. Quantifying Culture: Problems and Promises. J. Econ. Issues 2014, 48, 89–108.

- Tubadji, A.; Nijkamp, P. Cultural Corridors: An Analysis of Persistence in Impacts on Local Development—A Neo-Weberian Perspective on South-East Europe. J. Econ. Issues 2018, 52, 173–204.

- Alesina, A.; Perotti, R. The Political Economy of Growth: A Critical Survey of the Recent Literature. World Bank Econ. Rev. 1994, 8, 351–371.

- Guiso, L.; Sapienza, P.; Zingales, L. Does Culture Affinity Economic Outcomes? J. Econ. Perspect. 2006, 20, 23–48.

- Alesina, A.; Giuliano, P. Culture and Institutions. J. Econ. Lit. 2015, 53, 898–944.

- Alesina, A.; Miano, A.; Stantcheva, S. The Polarization of Reality. AEA Pap. Proc. 2020, 110, 324–328.

- Nijkamp, P. Ceteris Paribus, Spatial Complexity and Spatial Equilibrium. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2007, 37, 509–516.

- Glick, L.B. Culture and Morality: The Relativity of Values in Anthropology. Elvin Hatch. Am. Ethnol. 1984, 11, 198–199.

- Littlewood, R.A. Culture and Morality: The Relativity of Values in Anthropology. Elvin Hatch. J. Anthr. Res. 1984, 40, 335–336.

- Van Staveren, I. The Values of Economics: An Aristotelian Perspective; Routledge: London, UK, 2001.

- Kuznets, S. Economic Growth and Income Inequality. Am. Econ. Rev. 2019, 1, 25–37.

- Kuznets, S. Quantitative Aspects of the Economic Growth of Nations: VIII. Distribution of Income by Size. Econ. Dev. Cult. Chang. 1963, 11, 1–80.

- Grossman, G.M.; Krueger, A.B. Economic Growth and the Environment. Q. J. Econ. 1995, 110, 353–377.

- Grossman, G.; Krueger, A. The Inverted-U: What Does It Mean? Environ. Dev. Econ. 1996, 1, 119–122.

- Strulik, H. Too Much of a Good Thing? The Quantitative Economics of R&D-Driven Growth Revisited. Scand. J. Econ. 2007, 109, 369–386.

- Qizilbash, M. Development, Common Foes and Shared Values. Rev. Political Econ. 2002, 14, 463–480.

- Shackle, G.L.S. Time and Thought. Br. J. Philos. Sci. 1959, 9, 285–298.

- Tubadji, A. Was Weber Right? The Cultural Capital Roots of Economic Growth. Int. J. Manpow. 2014, 35, 56–88.

- Borowiecki, K.J. How Are You, My Dearest Mozart? Well-Being and Creativity of Three Famous Composers Based on Their Letters. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2017, 99, 591–605.

- Obstfeld, M.; Rogoff, K. The Six Major Puzzles in International Macroeconomics: Is There a Common Cause. In NBER Macroeconomics Annual; Bernanke, B., Rogoff, K., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003.

- Bernstein, S.; Lerner, J.; Schoar, A. The Investment Strategies of Sovereign Wealth Funds. J. Econ. Perspect. 2013, 27, 219–238.

- Morrison, P.S.; Weckroth, M. Human Values, Subjective Well-Being and the Metropolitan Region. Reg. Stud. 2018, 52, 325–337.