| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sirius Huang | -- | 1616 | 2022-11-24 01:38:08 |

Video Upload Options

Halemaʻumaʻu Crater (six syllables: HAH-lay-MAH-oo-MAH-oo) is a pit crater located within the much larger summit caldera of Kīlauea in Hawaii Volcanoes National Park. The roughly circular crater was 770 meters (2,530 ft) x 900 m (2,950 ft) prior to collapses that roughly doubled the size of the crater after May 3, 2018. Halemaʻumaʻu is home to Pele, goddess of fire and volcanoes, according to the traditions of Hawaiian religion. Halemaʻumaʻu means "house of the ʻāmaʻu fern". The crater until recently contained an active lava lake. From 2008, when the current vent inside Halemaʻumaʻu crater first erupted, to April 2015, lava was present inside the vent, fluctuating from 20 to 150 meters below the crater rim. On April 24, 2015 molten lava in the vent, known as the Overlook Crater, became directly visible for the first time from the Jaggar Museum overlook at the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory, when the lava rose to an all-time high level since the Overlook Crater first opened. A few days later, on April 29, the lava started spilling over the rim of the Overlook Crater and onto the floor of Halemaʻumaʻu Crater, ultimately adding a layer of lava approximately 30 feet (9 m) thick to the crater floor. For three years from 2015 to 2018 the lava lake level remained close to the rim, with a further minor overflow event in October 2016 and a significant one in April 2018 that covered a majority of the crater floor in new lava. In early May 2018 the lava level in the Overlook Crater dropped over 700 feet and out of sight, resulting in explosions, earthquakes and large clouds of ash and toxic gas, causing closure of the Kīlauea summit area of the national park from May 10 to September 22. While the park visitor center and headquarters have reopened to the public, the crater is currently in a state of collapse that includes substantial portions of Kīlauea Caldera. The Jaggar Museum overlooking the crater remains closed.

1. Early History

Early eruptions were recorded by oral history. A large one in 1790 killed several people, and left footprints in hardened ash of some Hawaiians killed by pyroclastic flows.

William Ellis, a British missionary and amateur ethnographer and geologist, published the first English description of Halemaʻumaʻu as it appeared in 1823.[1]

Astonishment and awe for some moments rendered us mute, and like statues, we stood fixed to the spot, with our eyes riveted on the abyss below. Immediately before us yawned an immense gulf, in the form of a crescent, about two miles (3 km) in length, from north-east to south-west, nearly a mile in width, and apparently 800 feet (240 m) deep. The bottom was covered with lava, and the south-west and northern parts of it were one vast flood of burning matter, in a state of terrific ebullition, rolling to and fro its "fiery surge" and flaming billows.

In 1866, Mark Twain, an American humorist, satirist, lecturer, and writer hiked to the Caldera floor.[2]

He wrote the following account of the lake of molten lava which he found there:

It was like gazing at the sun at noon-day, except that the glare was not quite so white. At unequal distances all around the shores of the lake were nearly white-hot chimneys or hollow drums of lava, four or five feet high, and up through them were bursting gorgeous sprays of lava-gouts and gem spangles, some white, some red and some golden--a ceaseless bombardment, and one that fascinated the eye with its unapproachable splendor. The more distant jets, sparkling up through an intervening gossamer veil of vapor, seemed miles away; and the further the curving ranks of fiery fountains receded, the more fairy-like and beautiful they appeared.

Another missionary, Titus Coan, observed and wrote about eruptions in the 19th century.[3] Geologist Thomas Jaggar opened an observatory in 1912, and the area became Hawaii Volcanoes National Park in 1916.

The level of the lava lake varied over the decades and at times was only 30 meters (100 ft) below the crater rim. In 1924,[4] unusual explosive eruptions sent dust high into the atmosphere and doubled the diameter of the crater. Fractures allowed the lava lake to drain to the east until its surface was 366 m (1,200 ft) below the caldera floor. Subsequent eruptions have mostly refilled the crater. Most of the current crater floor was formed in 1974.[5] A 1982 eruption covered a small portion of the northeastern crater floor.[6]

2. Crater Eruption - 2008 to Present

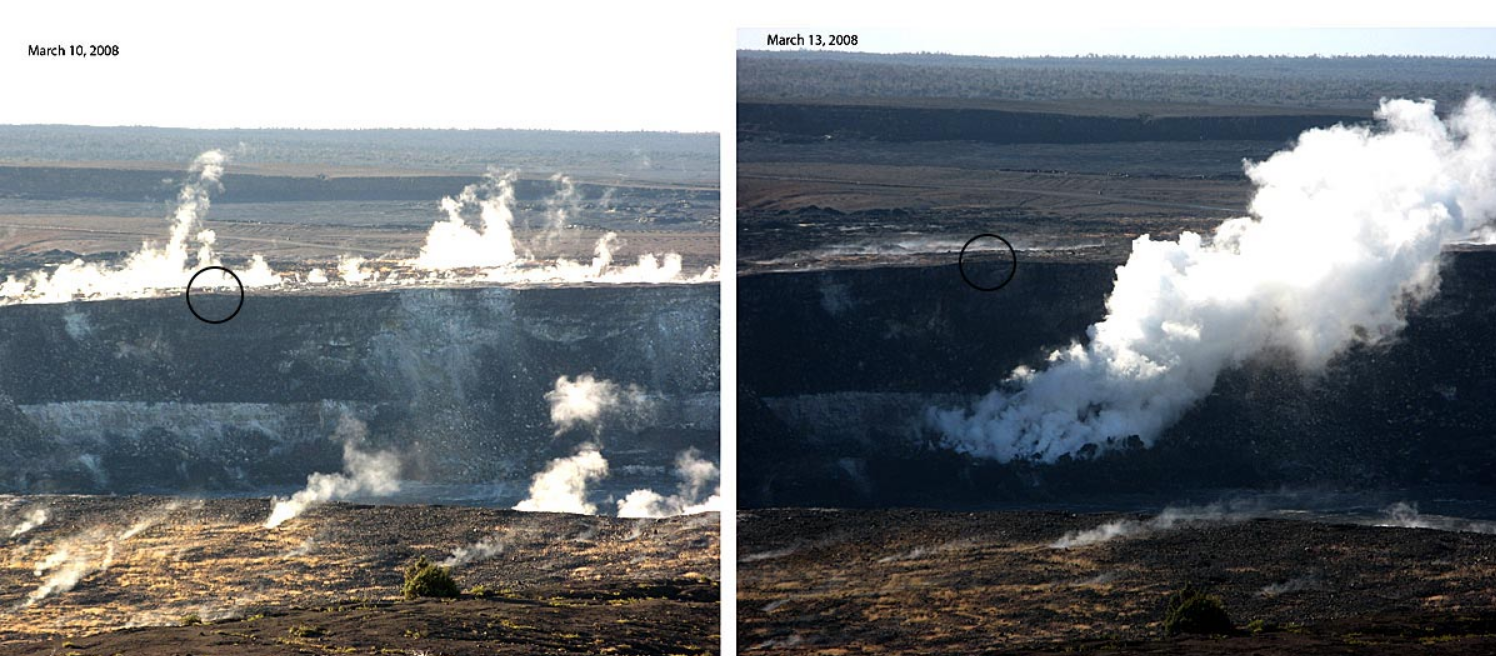

2.1. March 2008 Eruption Episode

Crater activity began to increase when between March 10 and March 14, 2008 gas began to vent from the east wall fumarole directly below the Crater Overlook.[7] At 02:58 am HST on March 19, 2008, HVO personnel recorded seismic events, and sunrise revealed a 20–30 meter (65–100 foot) diameter hole blown in the side where the vent once was; the explosion scattered debris and spatter across 0.30 square kilometers (74 acres) and damaged the Crater Overlook.[8] Pieces as large as 20 millimeters (1 in) were found on Crater Rim Drive while 0.3 m (1 ft) blocks hit the crater overlook area.[9] This was the first explosive eruption of Halemaʻumaʻu Crater since 1924, and the first lava eruption from the crater since 1982.[10]

Sulfur dioxide gas emissions increased rapidly at the beginning of the episode. On March 13, HVO recorded a rate of 2,000 tons/day, the highest rate since measurements began in 1979. A concentration of over 40 ppm on Crater Rim Drive was measured, prompting alerts and other public safety measures.[7][11] Halemaʻumaʻu crater continued to intermittently emit high levels of volcanic gases, ash, spatter, Pele's Tears, and Pele's Hair until the second episode.[12]

2.2. April 2008 Eruption Episode

This episode began with an explosion on the night of April 9, 2008 that widened the hole by an additional 5–10 meters (15–30 feet), ejected debris over some 60 m (200 ft) and further damaged the overlook as well as scientific monitoring instruments.[13]

In response to the second episode, scientists and local government officials on April 9, 2008 ordered hundreds of people to evacuate from the Park and nearby villages because the sulfur dioxide concentration levels had reached a critical level and a hazardous vog plume extended downwind from the crater. The evacuation lasted two days.[11]

On April 16, 2008 the crater was rocked with its third significant explosive event, sending ash and debris throughout the area.

A second evacuation of the park and surrounding areas was ordered on April 23, 2008.[14]

Before and after view of second explosion on April 9, 2008. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1382488

At night, an incandescent glow illuminates the venting gas plume on September 21, 2008. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1647005

2.3. May–August 2008

Activity within the crater and vent continued to present scientists with work as the vent continued to eject ash and gases. It wasn't until August 1, 2008 that the crater was rocked with the 4th explosive event and later on August 27, 2008 its 5th.

2.4. September 2008 Eruption Episode

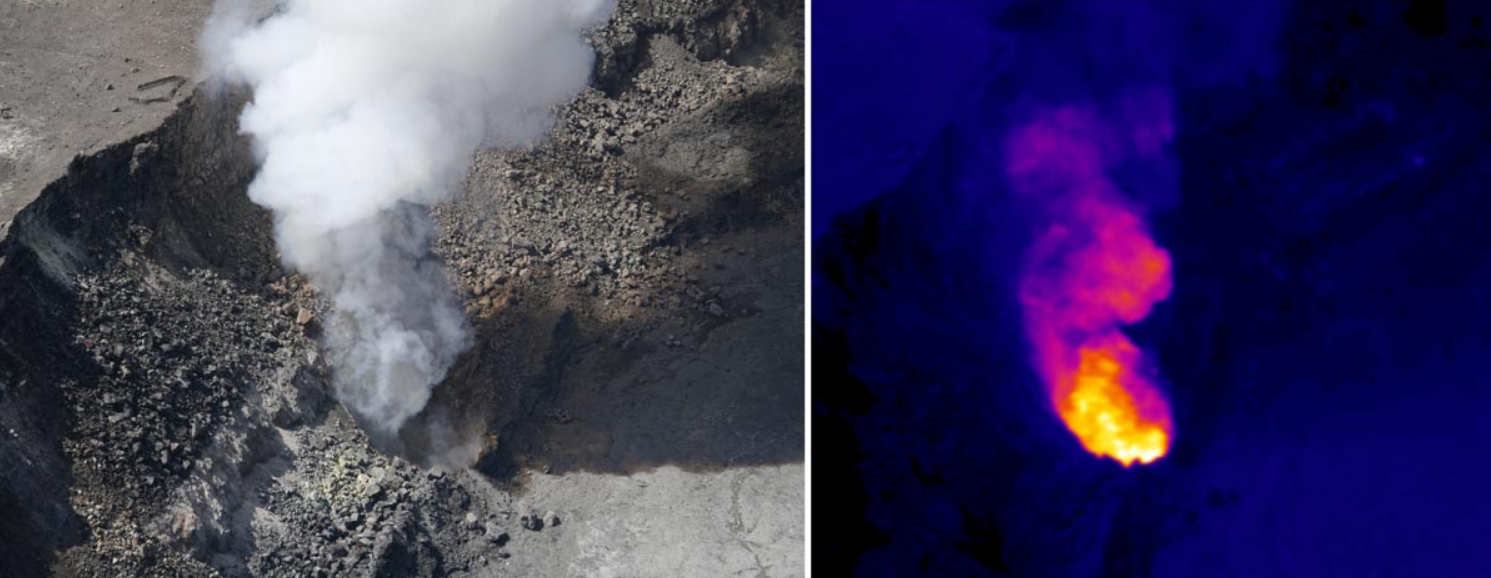

A Hawaii Volcano Observatory news release and images dated September 5, 2008 confirmed the first recorded images of a lava lake 130 feet below the lip of the vent. The HVO had alluded to the presence of lava within the vent, including the sporadic ejecting of lava materials from the vent due to explosive episodes, but this gave officials the first opportunity to visually confirm that active lava was present. The report also noted that the lava could not be seen from observation points around the crater.[15]

Since the vent's first appearance there were six significant explosive events to September 2, 2008, changing the vent significantly.

2.5. April–July 2018 Eruption Episode

In April 2018, the lava lake at Halema'uma'u Crater rose to an all-time high level prior to the May eruption. At its peak, the lava covered two-thirds of the crater floor with fresh lava. The flow of lava was accompanied by pyrotechnics at the summit, although most of the property and life threatening activity stemmed from May fissures, lava fountains and poisonous gases in the East Rift zone. [16]

On April 30, the Pu'u O'o crater collapsed and shortly thereafter lava began to emerge from rifts in Leilani Estates; the USGS status update on the evening of May 6 reported that Halemaʻumaʻu‘s Overlook Crater lava lake had dropped by 722 feet (220 m) since April 30.[17][18]

3. Ongoing Activity

Activity in the crater's vent has been almost constant since March 2008, though it has enlarged since the 2008 events and contained a semi-permanent lava lake, which was visible from the Jaggar Center overlook for about a week from 23 April 2015.[19] Other than the described events, major fountaining of lava has not occurred in the crater, unlike the concurrent activity on the Eastern Rift Zone around Puʻu ʻŌʻō. Explosive events have occurred as a result of crater wall cave-ins, however.

The crater's webcams show ongoing activity, including the active lava lake as seen from the Observatory[20] and as seen from the crater rim, looking down into the vent.[21] The Halemaʻumaʻu Overlook and its parking lot were lost when segments of the crater rim slumped into the crater, [22] while Crater Rim Drive is closed along with the closure of the entire Kīlauea section of the Park.

In May 2015 and October 2016, the lava lake overflowed onto the surrounding floor of the crater.

In April 2018, a significant series of overflows had reportedly covered most of the Halema'uma'u Crater floor with new lava.[23]

References

- William Ellis (1823). A journal of a tour around Hawai'i, the largest of the Sandwich Islands. Crocker and Brewster, New York, republished 2004, Mutual Publishing, Honolulu. ISBN 1-56647-605-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=dN8wuzrh6m8C&pg=PR1.

- Mark Twain (1872). "LXXV". Roughing It. David Widger. http://www.fullbooks.com/Roughing-It-Part-8-.html.

- Coan, Titus (1882). Life in Hawaii. New York: Anson Randolph & Company. http://www.soest.hawaii.edu/GG/HCV/COAN/coan-intro.html.

- "The 1924 explosions of Kilauea". Hawaiian Volcano Observatory. May 1924. http://hvo.wr.usgs.gov/kilauea/history/1924May18/. Retrieved 2008-04-25.

- Knabel, Sarah (2005-11-23). "Field Stop 12: Halema'uma'u Crater". Geography Capstone October 23, 2005. Archived from the original on December 11, 2012. https://archive.is/20121211114058/http://www.uwec.edu/jolhm/Hawaii2005/Day3/HIwebsite/FS12.htm. Retrieved 2009-07-09.

- "Summary of Historical Eruptions, 1750 - Present". Hawaiian Volcano Observatory. 18 April 2005. http://hvo.wr.usgs.gov/kilauea/history/historytable.html. Retrieved 2008-04-23.

- "New gas vent in Halemaʻumaʻu crater doubles sulfur dioxide emission rates". Hawaii Volcano Observatory (HVO) (HVO, USGS). March 14, 2008. http://hvo.wr.usgs.gov/pressreleases/pr03_14_08.html.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2008-03-28. https://web.archive.org/web/20080328002649/http://volcanoes.usgs.gov/Products/Pglossary/spatter.html. Retrieved 2008-04-23.

- "Explosive eruption in Halema`uma`u Crater, Kilauea Volcano, is first since 1924". Hawaii Volcano Observatory (HVO) (HVO, USGS). March 19, 2008. http://hvo.wr.usgs.gov/pressreleases/pr03_19_08.html.

- Dondoneau, Dave (March 19, 2008). "1st explosive eruption since 1924 reported at Kilauea". The Honolulu Advertiser (Gannett Corporation). http://www.honoluluadvertiser.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20080319/BREAKING01/80319046/-1/BREAKING01. Retrieved 2008-04-18.

- Dayton, Kevin (April 9, 2008). "Volcano park evacuated; Blanket of toxic vog drifts over Big Isle but most residents stay put". The Honolulu Advertiser (Gannett Corporation). http://www.honoluluadvertiser.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20080409/NEWS01/804090433. Retrieved 2008-04-18.

- "Halemaʻumaʻu gas plume becomes ash-laden". Hawaii Volcano Observatory (HVO), USGS. March 24, 2008. http://hvo.wr.usgs.gov/pressreleases/pr03_24_08.html. Retrieved 2008-04-22.

- "Halema‘uma‘u Vent Explodes a Second Time". Hawaii Volcano Observatory (HVO), USGS. April 10, 2008. http://hvo.wr.usgs.gov/pressreleases/pr04_10_08.html. Retrieved 2008-04-22.

- "KITV News, April 23, 2008". Kitv.com. 2008-04-23. http://www.kitv.com/r/15972877/detail.html. Retrieved 2013-12-27.

- "Sloshing lava lake viewed within Halema'uma'u vent". Hawaii Volcano Observatory (HVO), USGS. September 5, 2008. http://hvo.wr.usgs.gov/pressreleases/pr09_05_08.html. Retrieved 2008-09-06.

- "Volcanologist: Why live near Hawaii’s volcano". CNN Wire. May 6, 2018. http://cw39.com/2018/05/06/volcanologist-why-live-near-hawaiis-volcano/. Retrieved 2018-05-06.

- [1]

- Changes in the Kīlauea caldera from May 14 to July 19, 2018 (Planet Labs Inc.) https://www.planet.com/stories/kilauea-caldera-p_5H8jpig

- "HVO Kilauea Status". http://hvo.wr.usgs.gov/activity/kilaueastatus.php. April 24th Update

- "HVO Webcams". Volcanoes.usgs.gov. http://volcanoes.usgs.gov/hvo/cams/KIcam/. Retrieved 2013-12-27.

- "HVO Webcams". Volcanoes.usgs.gov. http://volcanoes.usgs.gov/hvo/cams/HMcam/. Retrieved 2013-12-27.

- http://www.staradvertiser.com/2018/07/02/hawaii-news/kilauea-eruption-has-shaken-volcano-village/

- "Summit lava lake still overflowing into crater". Star Advertiser. April 26, 2018. http://www.staradvertiser.com/2018/04/26/hawaii-news/summit-lava-lake-still-overflowing-into-crater/. Retrieved 27 April 2018.