Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Zied Ltaief | -- | 2413 | 2022-11-23 21:35:51 | | | |

| 2 | Conner Chen | Meta information modification | 2413 | 2022-11-28 01:12:44 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Ltaief, Z.; Ben-Hamouda, N.; Rancati, V.; Gunga, Z.; Marcucci, C.; Kirsch, M.; Liaudet, L. Pathophysiology of Vasoplegic Syndrome after Cardiopulmonary Bypass. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/36138 (accessed on 08 February 2026).

Ltaief Z, Ben-Hamouda N, Rancati V, Gunga Z, Marcucci C, Kirsch M, et al. Pathophysiology of Vasoplegic Syndrome after Cardiopulmonary Bypass. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/36138. Accessed February 08, 2026.

Ltaief, Zied, Nawfel Ben-Hamouda, Valentina Rancati, Ziyad Gunga, Carlo Marcucci, Matthias Kirsch, Lucas Liaudet. "Pathophysiology of Vasoplegic Syndrome after Cardiopulmonary Bypass" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/36138 (accessed February 08, 2026).

Ltaief, Z., Ben-Hamouda, N., Rancati, V., Gunga, Z., Marcucci, C., Kirsch, M., & Liaudet, L. (2022, November 23). Pathophysiology of Vasoplegic Syndrome after Cardiopulmonary Bypass. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/36138

Ltaief, Zied, et al. "Pathophysiology of Vasoplegic Syndrome after Cardiopulmonary Bypass." Encyclopedia. Web. 23 November, 2022.

Copy Citation

Vasoplegic syndrome (VS) is a common complication following cardiovascular surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB), and its incidence varies from 5 to 44%. It is defined as a distributive form of shock due to a significant drop in vascular resistance after CPB.

vasoplegic syndrome

cardio-pulmonary bypass

cardiac surgery

vasopressin

1. Introduction

Vasoplegic syndrome (VS) complicating cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) is a frequently described syndrome with many used denominations: low vascular resistance syndrome, catecholamine refractory vasoplegia, cardiac vasoplegia syndrome, inflammatory response to bypass, systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) after cardiac surgery, post perfusion syndrome and vasoplegic shock post-bypass [1][2][3][4][5][6]. The clinical pattern is that of a distributive form of circulatory shock developing in the first 24 h after CPB [7], characterized by hypotension (mean arterial pressure < 65 mmHg resistant to fluid challenge), systemic vascular resistance < 800 dynes s/cm5 and a cardiac index > than 2.2 l/min/m2 [1][8].

The incidence of VS after CPB varies from 5 to 44% [1][8] and it accounts for 4.6% of all forms of circulatory shock [9]. A higher incidence has been reported in patients with low preoperative left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction (EF) and in those undergoing LV assist device surgery [10][11]. Several predisposing factors have been identified, such as advanced age, prolonged aortic cross-clamp and CPB time, as well as the pre-operative use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI) and diuretics [8][10][12]. Patients experiencing VS display an increased incidence of postoperative complications and, consequently, a longer intensive care unit (ICU) stay [8], as well as greater post-operative mortality (5.6–15%) [2][13] than in the overall cardiac surgery population (3.4–6.2%) [14][15]. Table 1 summarizes the main clinical characteristics, pathophysiological mechanisms, and principles of management of VS after CPB.

Table 1. Vasoplegic shock after cardiopulmonary bypass—main characteristics.

| Definition | Distributive Form of Circulatory Shock ≤ 24 h after CPB Initiation, Characterized by:

|

| Predisposing factors | |

| Patient-related factors | Advanced age; anemia; low LVEF; renal failure |

| Pre-/peri-operative drugs | Diuretics; sympatho-adrenergic inotropes; ACEI (controversial) |

| Operative factors | CPB/aortic cross clamping time; redo surgery; combined surgery; LVAD surgery; HTx |

| Pathophysiology | |

| Initiating events | Systemic inflammatory response triggered by:

|

| Mechanisms of pathological vasodilation |

|

| Outcome |

|

| Management |

|

Abbreviations: ACEI: Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors; Ang 2: Angiotensin 2; CI: Cardiac Index; CPB: CardioPulmonary Bypass; H2S: Hydrogen Sulfide; HTx: Heart Transplantation; ICU: Intensive Care Unit; MAP: Mean Arterial Pressure; LVAD: Left Ventricular Assist Device; LVEF: Left Ventricle Ejection Fraction; NO: Nitric Oxide; RAS: Renin−Angiotensin System; SVR: Systemic Vascular Resistance; VA−PCO2 gap: Venous to Arterial Difference in the Partial Pressure of Carbon Dioxide; VS: Vasoplegic Syndrome; VSMC: Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell. *: In some patients with severe cardiac dysfunction, vasoplegia may be present in spite of a low cardiac output (CI < 2.2 L/min/m2). These patients therefore do not fulfill the complete hemodynamic criteria of pure VS, and should be considered as presenting a mixed form of shock. **: Strong recommendation ***: Insufficient evidence; risk of harm incompletely documented; can be used on a case−by−case basis as a rescue therapy; need for additional adequately powered randomized controlled trials (RCTs). ****: Acts via anti−inflammatory actions + increased vascular responsiveness to vasoconstrictors; accelerates resolution of shock in sepsis, controversial effects on mortality; precise role in VS post−CPB presently undefined; may be used as adjunctive treatment to conventional vasopressors in refractory cases; need for additional adequately powered RCTs.

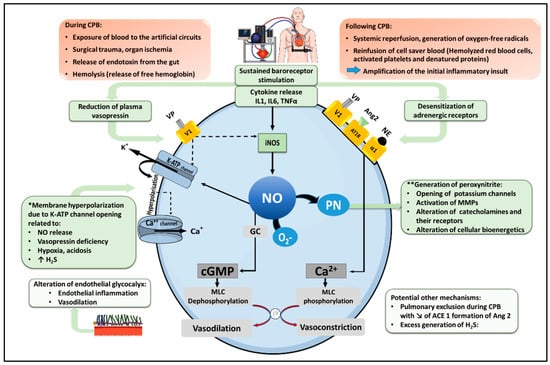

2. Pathophysiology of Vasoplegic Syndrome after CPB (Figure 1)

Figure 1. Pathophysiological mechanism of vasoplegia after cardio-pulmonary bypass. Under normal conditions, norepinephrine (NE), angiotensin 2 (Ang2) and vasopressin (VP) activate their respective receptors in vascular smooth muscle cells, namely the α1-adrenoreceptor, the Ang2 type I receptor (AT1R) and the vasopressin V1 receptor, to promote an increase in cytosolic Ca++, leading to Myosin Light Chain (MLC) phosphorylation, actin-myosin interaction and smooth muscle contraction. In addition, vasopressin exerts indirect vasoconstrictor actions by inhibiting two physiological mechanisms of vasodilation, including NO production and the opening of ATP-dependent potassium channels (KATP). Following cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB), cytokine release and sustained baroreceptor stimulation foster a down-regulation and desensitization of adrenergic receptors, as well as a reduction in plasma VP, reducing catecholamine and vasopressin-mediated vasoconstriction. In addition, inflammatory cytokines stimulate the expression of the inducible isoform of NO synthase (iNOS), leading to excessive NO production. NO activates soluble guanylyl cyclase (GC), generating cyclic GMP (cGMP), which dephosphorylates MLC with subsequent vasodilation. Moreover, NO activates KATP channels, causing K+ efflux, membrane hyperpolarization, and the closure of Ca++ channels, thereby reduce cytosolic Ca++. KATP channels opening and membrane hyperpolarization can also result from additional mechanisms, as indicated (*). NO further reacts with the superoxide anion radical (O2−) to form peroxynitrite (PN), which contributes to vasodilation via multiple processes, as indicated (**). CPB can also trigger alterations of the glycocalyx (favoring endothelial dysfunction and vascular inflammation), promote the production of hydrogen sulfide (H2S) with vasodilating properties, and reduce Ang2 formation by type I angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE 1). Solid lines indicate activation; dashed lines indicate inhibition.

2.1. Physiology of Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Contraction

The phosphorylation of the regulatory Myosin Light Chain (MLC) is the cornerstone of smooth muscle contraction. Vasoconstricting agents such as norepinephrine, angiotensin 2 and vasopressin activate cell surface G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) to induce an increase in intracellular Ca++ concentration in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs). In turn, Ca++ binds to calmodulin, forming a complex activating MLC Kinase to promote MLC phosphorylation, with subsequent actin-myosin interaction and smooth muscle contraction [16]. In contrast, vasodilators such as nitric oxide (NO) and natriuretic peptides trigger a guanylyl cyclase-dependent increase in cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP), which activates myosin phosphatase to dephoshorylate MLC, thereby preventing smooth muscle contraction [17][18]. CPB promotes a series of pathophysiological mechanisms concurring to alter smooth muscle Ca++ signaling and MLC phosphorylation, which may ultimately result in a state of vasoplegia, characterized by pathological vasodilation and reduced responsiveness to vasoconstrictors.

2.2. Inflammatory Pathways Triggered by CPB

Several mechanisms triggered at the time of CPB, and amplified upon its discontinuation, concur to trigger a systemic inflammatory response: the exposure of blood components to the artificial surfaces of the extracorporeal circuit, surgical trauma, organ ischemia, the release of endotoxin from the gut into the circulation, and hemolysis with liberation of free hemoglobin. Altogether, these mechanisms promote the activation of the complement cascade and the expression of pro-inflammatory mediators, such as interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) [6][19][20]. IL-6 is notably a potent inhibitor of vascular contraction by increasing the synthesis of cyclic AMP, which promotes vasodilation by reducing myoplasmic [Ca++] [21][22]. Accordingly, higher circulating levels of IL-6 have been associated with an increased incidence of VS and a higher need for vasopressors after CPB [23][24]. Longer CPB and aortic cross-clamping durations, combined surgery and redo intervention all predispose to a more intense inflammatory response and therefore represent independent risk factors for the development of VS [25]. Following the discontinuation of CPB, systemic reperfusion promotes the generation of oxygen-free radicals and the amplification of the initial inflammation. Moreover, the reinfusion of cell saver blood containing hemolyzed red blood cells, activated platelets and denatured proteins, may also contribute to this response [4][26]. Ultimately, such systemic inflammation engages a series of biological processes precipitating the loss of vascular tone, as detailed below.

2.3. Adrenoreceptor Desensitization

Inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6 and TNFα impair adrenoreceptor-dependent signaling by two mechanisms. The first one is related to a reduced expression of vascular α1-adrenoreceptors, consecutive to suppressed promoter activity at the level of gene transcription [27]. The second and most important mechanism relies in the desensitization of the receptors, triggered by the excessive release of catecholamines in response to baroreceptor and cytokine-dependent stimulation of the central sympathetic system. In turn, sustained adrenergic stimulation induces the phosphorylation of the G-protein coupled adrenoreceptor through the activation of GPCR kinases, inhibiting catecholamine binding and downstream signaling [26][28].

2.4. Increased Nitric Oxide Biosynthesis

Inflammatory cytokines stimulate the expression of the inducible isoform of NO synthase (iNOS) through the activation of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) [29]. In contrast to the low amounts of NO released by the constitutive, calcium-dependent NOS isoforms, the calcium-independent iNOS has the ability to produce copious quantities of NO over prolonged periods of time [29]. Elevated iNOS expression has been reported in lung tissue after CPB [30], and increased generation of NO has been shown to be proportional to the duration of CPB [31].

Several mechanisms account for the vasodilatory properties of NO. First and most importantly, NO activates soluble guanylyl cyclase in VSMCs to promote the formation of cyclic GMP, leading to MLC dephosphorylation [29]. Secondly, NO (via cGMP) activates adenosine triphosphate-sensitive potassium channels (KATP) in VSMCs, causing K+ efflux and membrane hyperpolarization. This results in the closure of voltage-activated calcium (Ca++) channels, the reduction in cytosolic Ca++ and vasodilation [32]. These effects are amplified by the ability of NO-cGMP to further promote K+ efflux by activating the vascular calcium-activated potassium channels (KCa++) [32]. An additional mechanism of NO-induced vasodilation is the generation of peroxynitrite, a strong oxidant and nitrating species formed from the rapid reaction of NO with the superoxide anion radical (O2−). Peroxynitrite contributes to vasoplegia by impairing bioenergetics in VSMCs, by activating matrix metalloproteinases, and by inativating catecholamines and their receptors [29].

2.5. Relative Deficiency of Vasopressin

Inflammatory cytokines and sustained baroreceptor stimulation are responsible for an overactivation of the central sympathetic system and the hypothalamo-pituitary axis, with subsequent release of high levels of norepinephrine, epinephrine, cortisol, and vasopressin [26]. Persistent shock and hypotension result in the progressive decline in the blood levels of these vasoactive mediators, a phenomenon particularly significant in the case of vasopressin [26]. Circulating vasopressin levels during CPB have been measured by Colson et al. in sixty-four consecutive patients. Patients developing VS displayed a significant drop of plasma vasopressin 8 h after CPB in comparison to non-VS patients (16 vs. 42 pmol/l, p = 0.01) [33]. Comparable results have been reported in patients with septic shock [34][35]. In turn, such decrease in vasopressin abrogates its vasopressor effects, which depend on the vascular V1 receptor (V1R), whose activation results in a protein kinase C (PKC)-dependent increase in intracellular calcium, both directly via Ca++ channel opening, and indirectly via KATP channel inhibition [36]. In addition, V1R-dependent PKC activation may inhibit MLC phosphatase, reduce iNOS expression and NO formation in response to inflammatory cytokines, promote the release of vasoconstrictors by endothelial cells (endothelin-1) and platelets (thromboxane A2), and ultimately can increase the vascular sensitivity to catecholamines [37][38][39][40].

2.6. Activation of KATP Channels and Membrane Hyperpolarization in VSMCs

The regulation of membrane potential in VSMCs depends on the activity of several types of K+ channels whose opening promotes K+ efflux and membrane hyperpolarization, resulting in the inhibition of Ca++-channel-dependent cellular influx of Ca++ and subsequent vasodilation. These channels include voltage dependent (Kv), Ca++ activated (KCa), inward rectifier (Kir) and ATP-sensitive (KATP) K+ channels [41]. Among these channels, the activation of KATP channel has been closely linked to the development of pathological vasodilation and the induction of hypotension in various forms of distributive shock [17]. Several mechanisms may account for the activation of KATP channel in VS associated with CPB, including NO release, vasopressin deficiency, hypoxia, acidosis and an increase in the generation of hydrogen sulfide (see below) [17][36][42][43][44][45].

2.7. Dysfunction of the Renin-Angiotensin System

Angiotensinogen, an inactive peptide produced by the liver, is cleaved by renin into angiotensin 1 (Ang1), and then to angiotensin 2 (Ang2) by the action of type 1 angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE 1) in the lung endothelium. In turn, Ang2 targets the vascular AT1 receptor, resulting in increased cytosolic Ca++ and vasoconstriction. Under conditions of impaired ACE 1 activity (pulmonary dysfunction), Ang2 formation is prevented, and Ang1 is converted into the vasodilating derivative Ang1–7 by the type 2 ACE (ACE 2) [46][47]. Such scenario might develop during the pulmonary exclusion associated with CPB, precipitating vasoplegia by reducing ACE 1 activity and Ang2 formation, while increasing Ang1 and Ang1–7. In addition, this process may be amplified by the enhanced secretion of renin, triggered in response to low Ang2 and reduced blood pressure, which further increases Ang1 formation (“high renin shock”) [47].

2.8. Endothelial Glycocalyx Alteration

The glycocalyx is a complex layer of glycosaminoglycans and proteoglycans coating the endothelial cell surface, with important components comprising heparan sulfate and syndecan-1. Heparan sulfate plays an important role in the regulation of vascular tone by modulating shear-stress dependent NO production, whereas syndecan-1 has been associated with anti-inflammatory effects by downregulating leukocyte adhesion and activation at the surface of the endothelium [48][49]. Circumstantial evidence indicates that CPB may induce damage to the glycocalyx, as reported in a pilot study by Boer et al., who found that glycocalyx thickness was significantly reduced after the initiation of CPB, a change which persisted after weaning and was associated with microcirculatory impairment [50]. Furthermore, Abou-Arab et al. reported that the plasma levels of syndecan-1 increased after CPB, consistent with glycocalyx shedding. Interestingly, patients developing VS had reduced baseline plasma syndecan-1 and a lesser increase after CPB, suggesting that altered glycocalyx structure with reduced syndecan-1 might predispose to endothelial inflammation and vasodilation after CPB [51].

2.9. Possible Role of an Excess Production of Hydrogen Sulfide

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) is a gaseous transmitter formed in the vascular system from the metabolism of cysteine and homocysteine by the enzymes cystathionine-gamma-lyase (CSE), cystathionine-beta-synthase (CBS), and 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase (3-MST) [52]. In blood vessels, H2S plays several homeostatic functions, notably acting as a vasodilator. This effect is related, on one hand, to the activation of KATP channels leading to membrane hyperpolarization [53], and on the other hand, to the enhancement, via multiple mechanisms, of vascular NO signaling [52]. An increased formation of H2S has been demonstrated in various animal models of septic shock, which might participate to the development of pathological vasodilation in such conditions [54]. Although not directly demonstrated in the setting of CPB, one can assume that the prevailing inflammatory conditions might enhance the synthesis of H2S as reported in sepsis. This would be consistent with the notion that hydroxocobalamin, which can bind H2S and inhibit its effects, can increase blood pressure in patients with severe VS post-CPB, as discussed later [55][56].

References

- Kristof, A.S.; Magder, S. Low systemic vascular resistance state in patients undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass. Crit. Care Med. 1999, 27, 1121–1127.

- Leyh, R.G.; Kofidis, T.; Strüber, M.; Fischer, S.; Knobloch, K.; Wachsmann, B.; Hagl, C.; Simon, A.R.; Haverich, A. Methylene blue: The drug of choice for catecholamine-refractory vasoplegia after cardiopulmonary bypass? J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2003, 125, 1426–1431.

- Nash, C.M. Vasoplegic Syndrome in Patients Undergoing Cardiac Surgery: A Literature Review. AACN Adv. Crit. Care 2021, 32, 137–145.

- Omar, S.; Zedan, A.; Nugent, K. Cardiac vasoplegia syndrome: Pathophysiology, risk factors and treatment. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2015, 349, 80–88.

- Petermichl, W.; Gruber, M.; Schoeller, I.; Allouch, K.; Graf, B.M.; Zausig, Y.A. The additional use of methylene blue has a decatecholaminisation effect on cardiac vasoplegic syndrome after cardiac surgery. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2021, 16, 205.

- Wan, S.; LeClerc, J.L.; Vincent, J.L. Inflammatory response to cardiopulmonary bypass: Mechanisms involved and possible therapeutic strategies. Chest 1997, 112, 676–692.

- Gomes, W.J.; Carvalho, A.C.; Palma, J.H.; Gonçalves, I., Jr.; Buffolo, E. Vasoplegic syndrome: A new dilemma. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 1994, 107, 942–943.

- Cremer, J.; Martin, M.; Redl, H.; Bahrami, S.; Abraham, C.; Graeter, T.; Haverich, A.; Schlag, G.; Borst, H.G. Systemic inflammatory response syndrome after cardiac operations. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 1996, 61, 1714–1720.

- De Backer, D.; Biston, P.; Devriendt, J.; Madl, C.; Chochrad, D.; Aldecoa, C.; Brasseur, A.; Defrance, P.; Gottignies, P.; Vincent, J.-L. Comparison of Dopamine and Norepinephrine in the Treatment of Shock. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 779–789.

- Argenziano, M.; Chen, J.M.; Choudhri, A.F.; Cullinane, S.; Garfein, E.; Weinberg, A.D.; Smith, C.R., Jr.; Rose, E.A.; Landry, D.W.; Oz, M.C. Management of vasodilatory shock after cardiac surgery: Identification of predisposing factors and use of a novel pressor agent. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 1998, 116, 973–980.

- Argenziano, M.; Choudhri, A.F.; Oz, M.C.; Rose, E.A.; Smith, C.R.; Landry, D.W. A prospective randomized trial of arginine vasopressin in the treatment of vasodilatory shock after left ventricular assist device placement. Circulation 1997, 96, II-286–II-290.

- Levin, M.A.; Lin, H.M.; Castillo, J.G.; Adams, D.H.; Reich, D.L.; Fischer, G.W. Early on-cardiopulmonary bypass hypotension and other factors associated with vasoplegic syndrome. Circulation 2009, 120, 1664–1671.

- Hajjar, L.A.; Vincent, J.L.; Barbosa Gomes Galas, F.R.; Rhodes, A.; Landoni, G.; Osawa, E.A.; Melo, R.R.; Sundin, M.R.; Grande, S.M.; Gaiotto, F.A.; et al. Vasopressin versus Norepinephrine in Patients with Vasoplegic Shock after Cardiac Surgery: The VANCS Randomized Controlled Trial. Anesthesiology 2017, 126, 85–93.

- Hansen, L.S.; Hjortdal, V.E.; Andreasen, J.J.; Mortensen, P.E.; Jakobsen, C.J. 30-day mortality after coronary artery bypass grafting and valve surgery has greatly improved over the last decade, but the 1-year mortality remains constant. Ann. Card. Anaesth. 2015, 18, 138–142.

- Mazzeffi, M.; Zivot, J.; Buchman, T.; Halkos, M. In-hospital mortality after cardiac surgery: Patient characteristics, timing, and association with postoperative length of intensive care unit and hospital stay. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2014, 97, 1220–1225.

- Touyz, R.M.; Alves-Lopes, R.; Rios, F.J.; Camargo, L.L.; Anagnostopoulou, A.; Arner, A.; Montezano, A.C. Vascular smooth muscle contraction in hypertension. Cardiovasc. Res. 2018, 114, 529–539.

- Landry, D.W.; Oliver, J.A. The pathogenesis of vasodilatory shock. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 345, 588–595.

- Surks, H.K.; Mochizuki, N.; Kasai, Y.; Georgescu, S.P.; Tang, K.M.; Ito, M.; Lincoln, T.M.; Mendelsohn, M.E. Regulation of myosin phosphatase by a specific interaction with cGMP- dependent protein kinase Ialpha. Science 1999, 286, 1583–1587.

- Hall, R.I.; Smith, M.S.; Rocker, G. The systemic inflammatory response to cardiopulmonary bypass: Pathophysiological, therapeutic, and pharmacological considerations. Anesth. Analg. 1997, 85, 766–782.

- Wan, S.; DeSmet, J.M.; Vincent, J.L.; LeClerc, J.L. Thrombus formation on a calcific and severely stenotic bicuspid aortic valve. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 1997, 64, 535–536.

- McDaniel, N.L.; Rembold, C.M.; Richard, H.M.; Murphy, R.A. Cyclic AMP relaxes swine arterial smooth muscle predominantly by decreasing cell Ca2+ concentration. J. Physiol. 1991, 439, 147–160.

- Ohkawa, F.; Ikeda, U.; Kanbe, T.; Kawasaki, K.; Shimada, K. Effects of inflammatory cytokines on vascular tone. Cardiovasc. Res. 1995, 30, 711–715.

- Weis, F.; Kilger, E.; Beiras-Fernandez, A.; Nassau, K.; Reuter, D.; Goetz, A.; Lamm, P.; Reindl, L.; Briegel, J. Association between vasopressor dependence and early outcome in patients after cardiac surgery. Anaesthesia 2006, 61, 938–942.

- Kilger, E.; Weis, F.; Briegel, J.; Frey, L.; Goetz, A.E.; Reuter, D.; Nagy, A.; Schuetz, A.; Lamm, P.; Knoll, A.; et al. Stress doses of hydrocortisone reduce severe systemic inflammatory response syndrome and improve early outcome in a risk group of patients after cardiac surgery. Crit. Care Med. 2003, 31, 1068–1074.

- Dayan, V.; Cal, R.; Giangrossi, F. Risk factors for vasoplegia after cardiac surgery: A meta-analysis. Interact Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2019, 28, 838–844.

- Busse, L.W.; Barker, N.; Petersen, C. Vasoplegic syndrome following cardiothoracic surgery-review of pathophysiology and update of treatment options. Crit. Care 2020, 24, 36.

- Kandasamy, K.; Prawez, S.; Choudhury, S.; More, A.S.; Ahanger, A.A.; Singh, T.U.; Parida, S.; Mishra, S.K. Atorvastatin prevents vascular hyporeactivity to norepinephrine in sepsis: Role of nitric oxide and α₁-adrenoceptor mRNA expression. Shock 2011, 36, 76–82.

- Levy, B.; Fritz, C.; Tahon, E.; Jacquot, A.; Auchet, T.; Kimmoun, A. Vasoplegia treatments: The past, the present, and the future. Crit. Care 2018, 22, 52.

- Pacher, P.; Beckman, J.S.; Liaudet, L. Nitric oxide and peroxynitrite in health and disease. Physiol. Rev. 2007, 87, 315–424.

- Delgado, R.; Rojas, A.; Glaría, L.A.; Torres, M.; Duarte, F.; Shill, R.; Nafeh, M.; Santin, E.; González, N.; Palacios, M. Ca(2+)-independent nitric oxide synthase activity in human lung after cardiopulmonary bypass. Thorax 1995, 50, 403–404.

- Hill, G.E.; Snider, S.; Galbraith, T.A.; Forst, S.; Robbins, R.A. Glucocorticoid reduction of bronchial epithelial inflammation during cardiopulmonary bypass. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1995, 152, 1791–1795.

- Sobey, C.G. Potassium Channel Function in Vascular Disease. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2001, 21, 28–38.

- Colson, P.H.; Bernard, C.; Struck, J.; Morgenthaler, N.G.; Albat, B.; Guillon, G. Post cardiac surgery vasoplegia is associated with high preoperative copeptin plasma concentration. Crit. Care 2011, 15, R255.

- Landry, D.W.; Levin, H.R.; Gallant, E.M.; Ashton, R.C., Jr.; Seo, S.; D’Alessandro, D.; Oz, M.C.; Oliver, J.A. Vasopressin deficiency contributes to the vasodilation of septic shock. Circulation 1997, 95, 1122–1125.

- Cuda, L.; Liaudet, L.; Ben-Hamouda, N. . Rev. Med. Suisse 2020, 16, 652–656.

- Wakatsuki, T.; Nakaya, Y.; Inoue, I. Vasopressin modulates K(+)-channel activities of cultured smooth muscle cells from porcine coronary artery. Am J. Physiol. 1992, 263, H491–H496.

- Barrett, L.K.; Singer, M.; Clapp, L.H. Vasopressin: Mechanisms of action on the vasculature in health and in septic shock. Crit. Care Med. 2007, 35, 33–40.

- Emori, T.; Hirata, Y.; Ohta, K.; Kanno, K.; Eguchi, S.; Imai, T.; Shichiri, M.; Marumo, F. Cellular mechanism of endothelin-1 release by angiotensin and vasopressin. Hypertension 1991, 18, 165–170.

- Imai, T.; Hirata, Y.; Emori, T.; Yanagisawa, M.; Masaki, T.; Marumo, F. Induction of endothelin-1 gene by angiotensin and vasopressin in endothelial cells. Hypertension 1992, 19, 753–757.

- Siess, W.; Stifel, M.; Binder, H.; Weber, P.C. Activation of V1-receptors by vasopressin stimulates inositol phospholipid hydrolysis and arachidonate metabolism in human platelets. Biochem. J. 1986, 233, 83–91.

- Ko, E.A.; Han, J.; Jung, I.D.; Park, W.S. Physiological roles of K+ channels in vascular smooth muscle cells. J. Smooth Muscle Res. 2008, 44, 65–81.

- Davies, N.W. Modulation of ATP-sensitive K+ channels in skeletal muscle by intracellular protons. Nature 1990, 343, 375–377.

- Keung, E.C.; Li, Q. Lactate activates ATP-sensitive potassium channels in guinea pig ventricular myocytes. J. Clin. Investig. 1991, 88, 1772–1777.

- Landry, D.W.; Oliver, J.A. The ATP-sensitive K+ channel mediates hypotension in endotoxemia and hypoxic lactic acidosis in dog. J. Clin. Investig. 1992, 89, 2071–2074.

- Tang, G.; Wu, L.; Liang, W.; Wang, R. Direct stimulation of K(ATP) channels by exogenous and endogenous hydrogen sulfide in vascular smooth muscle cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 2005, 68, 1757–1764.

- Liaudet, L.; Szabo, C. Blocking mineralocorticoid receptor with spironolactone may have a wide range of therapeutic actions in severe COVID-19 disease. Crit. Care 2020, 24, 318.

- Chow, J.H.; Wittwer, E.D.; Wieruszewski, P.M.; Khanna, A.K. Evaluating the evidence for angiotensin II for the treatment of vasoplegia in critically ill cardiothoracic surgery patients. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2022, 163, 1407–1414.

- Myers, G.J.; Wegner, J. Endothelial Glycocalyx and Cardiopulmonary Bypass. J. Extra Corpor. Technol. 2017, 49, 174–181.

- Voyvodic, P.L.; Min, D.; Liu, R.; Williams, E.; Chitalia, V.; Dunn, A.K.; Baker, A.B. Loss of Syndecan-1 Induces a Pro-inflammatory Phenotype in Endothelial Cells with a Dysregulated Response to Atheroprotective Flow. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 9547–9559.

- Boer, C.; Koning, N.J.; Van Teeffelen, J.; Vonk, A.B.; Vink, H. Changes in microcirculatory perfusion during cardiac surgery are paralleled by alterations in glycocalyx integrity. Crit. Care 2013, 17, P212.

- Abou-Arab, O.; Kamel, S.; Beyls, C.; Huette, P.; Bar, S.; Lorne, E.; Galmiche, A.; Guinot, P.G. Vasoplegia After Cardiac Surgery Is Associated with Endothelial Glycocalyx Alterations. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2020, 34, 900–905.

- Szabo, C. Hydrogen sulfide, an enhancer of vascular nitric oxide signaling: Mechanisms and implications. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2017, 312, C3–C15.

- Mustafa, A.K.; Sikka, G.; Gazi, S.K.; Steppan, J.; Jung, S.M.; Bhunia, A.K.; Barodka, V.M.; Gazi, F.K.; Barrow, R.K.; Wang, R.; et al. Hydrogen sulfide as endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor sulfhydrates potassium channels. Circ. Res. 2011, 109, 1259–1268.

- Coletta, C.; Szabo, C. Potential role of hydrogen sulfide in the pathogenesis of vascular dysfunction in septic shock. Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2013, 11, 208–221.

- Burnes, M.L.; Boettcher, B.T.; Woehlck, H.J.; Zundel, M.T.; Iqbal, Z.; Pagel, P.S. Hydroxocobalamin as a Rescue Treatment for Refractory Vasoplegic Syndrome After Prolonged Cardiopulmonary Bypass. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2017, 31, 1012–1014.

- Roderique, J.D.; VanDyck, K.; Holman, B.; Tang, D.; Chui, B.; Spiess, B.D. The Use of High-Dose Hydroxocobalamin for Vasoplegic Syndrome. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2014, 97, 1785–1786.

More

Information

Subjects:

Cardiac & Cardiovascular Systems

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.2K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

28 Nov 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No