Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Rodrigo Duarte-Casar | -- | 1625 | 2022-11-23 16:20:30 | | | |

| 2 | Beatrix Zheng | + 1 word(s) | 1626 | 2022-11-24 04:13:58 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

González-Jaramillo, N.; Bailon-Moscoso, N.; Duarte-Casar, R.; Romero-Benavides, J.C. Peach Palm (Bactris gasipaes Kunth.). Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/36126 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

González-Jaramillo N, Bailon-Moscoso N, Duarte-Casar R, Romero-Benavides JC. Peach Palm (Bactris gasipaes Kunth.). Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/36126. Accessed February 07, 2026.

González-Jaramillo, Nancy, Natalia Bailon-Moscoso, Rodrigo Duarte-Casar, Juan Carlos Romero-Benavides. "Peach Palm (Bactris gasipaes Kunth.)" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/36126 (accessed February 07, 2026).

González-Jaramillo, N., Bailon-Moscoso, N., Duarte-Casar, R., & Romero-Benavides, J.C. (2022, November 23). Peach Palm (Bactris gasipaes Kunth.). In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/36126

González-Jaramillo, Nancy, et al. "Peach Palm (Bactris gasipaes Kunth.)." Encyclopedia. Web. 23 November, 2022.

Copy Citation

A pre-Columbian staple, Bactris gasipaes Kunth. is a palm tree domesticated around 4000 years ago, so appreciated that a Spanish chronicler wrote in 1545, “only their wives and children were held in higher regard” by the Mesoamerican natives. The peach palm is an integral part of the foodways and gastronomy of Ecuador, Colombia, Bolivia, Peru, Brazil, and other tropical American countries; meanwhile, it is almost unknown in the rest of the world, except for hearts of palm. Although abundant, the species faces anthropogenic threats.

palm

Bactris gasipaes

food sovereignty

1. Introduction

The Amazon is a multicultural and multiethnic space where natural resources have been used ancestrally to provide housing, medicine, and food to its inhabitants [1]. Some of these are fruits that are currently considered promising for their sensory, nutritional, and ethnomedicinal characteristics [2][3][4]. Among these important species, palms are an important family. Palm trees are considered to be more useful to mankind than any other family, inspiring the tree of life motif [5]. An important palm in the Amazon and tropical America is Bactris gasipaes Kunth., in the Areacaceae family, the most important pre-Columbian American palm [6], a polyvalent pre-Columbian staple. This species, among many others, is expected to undergo changes in the land area suitable for cultivation due to climate change, with loss of current cultivation areas and the emergence of new ones [7]. This would not be the first climate event in Amazonia [8], and B. gasipaes overcame earlier events.

There is abundant research published on B. gasipaes, including excellent review articles [9][10]. The researchers found the need for an integrated, updated view that presents the current knowledge of the food and phytochemical study of the species. Most research on the species centers on its biology and agriculture.

2. Taxonomy and Distribution

Bactris gasipaes Kunth. Belongs to the Bactris Jacq. ex Scop. genus of spiny palms in the Arecaceae family, Cocoseae tribe. The genus includes seventy-nine species, of which several are edible. B. gasipaes is the most used species as a food resource in the genus. There are two accepted varieties of the species: Bactris gasipaes var. chichagui (H. Karst.) A.J. Hend. [11], and Bactris gasipaes var. gasipaes [12][13]. The chichagui variety is mostly wild with smaller, oilier fruit, and the gasipaes variety is cultivated, with larger and starchier fruit [14].

B. gasipaes currently extends throughout the Amazon basin and other humid lowlands of the neotropics, with one population up to 1800 m above sea level in Colombia. The species has been introduced to countries such as Australia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Reunion island, and Hawaii [15][16][17] to relieve the pressure on local palms endangered by non-sustainable production, especially where hearts of palm are produced.

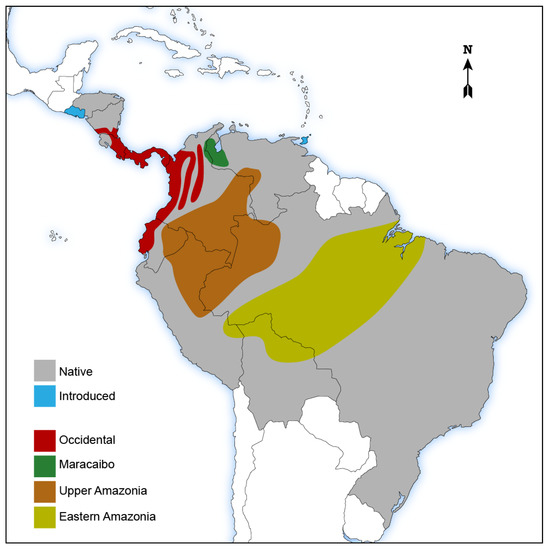

Common names for this species vary depending on the region, some of which are presented in Table 1. Figure 1 shows the distribution of B. gasipaes in tropical America by country, both as a native and as an introduced species.

Figure 1. Distribution of Bactris gasipaes Kunth., in tropical Central and South America. Grey: native; light blue: introduced (Trinidad and Tobago, El Salvador). Source: [18]. Shaded areas, main complexes: red: Occidental; green: Maracaibo; brown: Upper Amazonia; yellow: Eastern Amazonia. Source: [19].

Table 1. Common names of Bactris gasipaes according to location.

| Country | Names |

|---|---|

| Brazil | Papunha; Pupunha; Pupunheira; Popunha. |

| Bolivia | Chonta; Palma de Castilla; Tembe; Chima; Anua; Mue; Huanima; Pupuña; Tëmbi; Eat; Tempe. |

| Colombia | Cachipay; Chantaduro; Chenga; Chonta; Chontaduro; Chichagai; Pijiguay; Pupunha; Pupuña; Pejibá; Jijirre; Macanilla; Contaruro; Have; Pipire. |

| Costa Rica | Pejibaye; Pejivalle. |

| Ecuador | Chonta; Chonta dura; Chontaduro; Chonta palm; Palmito; Chantaduro, Puka chunta; Shalin chunta |

| Guyana | Paripie; Parepon. |

| Peru | Chonta; Ruru; Pejwao; Pifuayo; Chonta Duro; Joó; Uyai; Mee; Pijuayo; Pisho-Guayo; Sara-Pifuayo. |

| Suriname | Amana; Paripe; Paripoe. |

| Venezuela | Bobi; Cachipaes; Macana; Peach; Pijiguao; Pixabay; Rancanilla; Gachipaes; Pichiguao; Piriguao; Cachipay; Pachigaro. |

3. Morphological Description

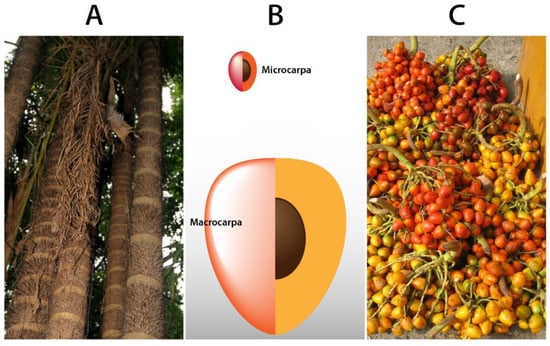

The species is characterized by being cespitose, i.e., several trunks (one to fifteen) with heights from six to twenty meters stemming from the point of origin, smooth in appearance, with evident internodes, surrounded by a ring of black thorns (Figure 2A) [15][19]. The leaves, located at the top of the trunk, are arched and long (up to 100 cm), their sheath covered with small white or dark brown spines; inflorescences appear in intrafoliar clusters and are monoecious: female and male flowers emerge from the same stem; with some structures, such as the peduncle, covered with spines. The species can produce up to ten inflorescences per year [16][20].

Figure 2. Morphology of Bactris gasipaes: (A). Trunks showing internodes covered with thorns. Source: David Stang (CC BY-SA 4.0); (B). Difference between macrocarpa and microcarpa fruits; (C). B. gasipaes fruit, microcarpa variety, Cali Colombia. Source: Michael Hermann (CC BY-SA 3.0).

Inside the trunk, the heart of palm can be found, a vegetable considered a delicacy: cylindrical and sweet-tasting, it consists of the apical meristem, divided into basal, central and apical with marked differences in texture due to the arrangement of the structural fibers; its harvest results in the death of some species [21][22], but not in Bactris spp., and other cespitose palms. This is why it has become a more sustainable prime source for hearts of palm, together with Euterpe oleracea (Açai).

The fruits are spherical or ovoid in shape, and come in a variety of sizes; the largest are up to10 cm long and up to 6 cm in diameter, they are clustered, green when unripe, and from yellow to orange when ripe [5][23]. The inside of the pulp is floury or oily depending on the variety, and in the center, there is a seed that resembles a very oily small coconut (Figure 2B). According to the weight of the fruit, B. gasipaes is categorized as microcarpa (<20 g), mesocarpa (>21 g, <70 g) and macrocarpa (>70 g) (Figure 2C), and also as orange, yellow, and lately, white varieties [24][25]. The fruit presents low polyphenol oxidase activity, which makes it suitable for minimally processed products [17].

The similarity with other species suggests the species was domesticated in areas of the Amazon through hybridization [5][26][27]. Its food use is mainly for its oil content, plus the harvesting process has ethnic, cultural, and traditional value [5][14][27][28]; in addition, it is attractive as a promising industrial resource for new products derived from the same species (chonta, palm heart, wood) [29][30].

4. Mythical Origins

There are several related origin myths for B. gasipaes in the traditions of Peruvian (Asháninka), Colombian (Yukuna Matapi), and Ecuadorian (Shuar Achuar) native peoples [31][32][33][34]. A common motif is that chonta and maize come from the otherworld, stolen by human or demigod visitors. In a Catío myth, the immortals of Armucurá, a planet below earth, feed on the vapors of B. gasipaes, but it is the human visitors that return with seeds for human cultivation and consumption [34]. In these stories, practical elements are transmitted: the quality of the wood for the making of proper weapons; the food value of the species; and the importance of not throwing the seeds away but saving them for cultivation. The interdependence of the cultivated palm and humans is shown in these stories, pointing to a domesticated species, no longer able to survive in the wild. Another example of how ingrained B. gasipaes is in the local cultures is the calendar use: “Pupunha summer” is part of the calendar of the indigenous peoples of the Tiquié river in Brazil [35], and the harvest season between December and March is an important event. Today, chonta festivities that reenact these myths survive and are becoming a community tourism product [36].

5. History

The origin of the species is unclear, but consensus points to the Bolivian amazon as a possible origin [5]. Three hypotheses coexist: a southwestern Amazon domestication, a northwestern South America domestication, and that of multiple origins. Two dispersals are supported by genetic diversity patterns: one along the Ucayali river, northwestern South America, and into Central America with a starchy, fermentable fruit used as a staple; another, along the Madeira river into central and eastern Amazonia in which the smaller, starchy, and oily fruit is used for snacking [14]. Similarity with other species suggests the species was domesticated in areas of the Amazon through hybridization, with highest genetical diversity in northern Peruvian and Ecuadorian Amazon. The domestication of the species is tentatively dated between 4000 and 3000 years BP, coincident with the establishment of sedentary communities in Amazonia [5][26][27]. The earliest archaeological remains of the species, presumably already cultivated, are dated 2300–1700 BC in Costa Rica [37].

The records about the species date back to the fifteenth century, and it is presumed that the beginning of its production under the Spanish was as timber, not as a food resource. During the Spanish conquest, native crops such as B. gasipaes lost importance, due to the massive native population loss [8] and the adoption of European productive systems. The European contact in the fifteenth–sixteenth centuries in Central America is marked by the awe of the Spaniards towards how appreciated the species was. Spanish chronicler Godínez Osorio wrote in 1575 that, “only their wives and children were held in higher regard” [38]. The timber of B. gasipaes was used in the early 1540s by the Spaniards to build fortifications because of its hardness and the fact that the trunk is naturally covered by thorns. It was also used as a weapon: more than 30,000 palms were cut down to submit the natives to hunger [39]. The same chronicle attests to the consumption of hearts of palm by a Chichimeca army under the orders of the Spaniards. Before the Spanish invasion, the fruit of B. gasipaes was a staple, and the harvest was one of the most important events of the year, with most births taking place nine months after it. Even today, 500 years later, the use of the species has not reached back to its pre-Hispanic level [14][16][40]. B. gasipaes fruit has been relegated pejoratively as a “fruit of the Indians”, a forgotten, neglected fruit [38][41]; however, in times of scarcity it has been used to provide food security [42], and it still is today [9].

References

- Aguirre Mendoza, Z.; León Abad, N. Sobrevivencia y Crecimiento Inicial de Especies Vegetales En El Jardín Botánico de La Quinta El Padmi, Zamora Chinchipe. Arnaldoa 2011, 18, 117–124.

- Clavijo, J.; Yánez, P. Plantas Frecuentemente Utilizadas En Zonas Rurales de La Región Amazónica Centro Occidental de Ecuador. INNOVA Res. J. 2017, 2, 9–21.

- Brito, B.; Paredes, N.; Vargas, Y. Calidad y Valor Agregado de Los Frutales Amazónicos. In Proceedings of the Primer Congreso Internacional Alternativas Tecnológicas para la Producción Agropecuaria Sostenible en la Amazonía Ecuatoriana; Caicedo, C., Buitrón, L., Díaz, A., Velástegui, F., Yánez, C., Cuasapaz, P., Eds.; Estación Central de la Amazonía INIAP: Orellana, Sacha, Ecuador, 2018; Volume 1, pp. 1–3.

- Toledo, D.; Brito, B. Aprovechamiento Del Potencial Nutritivo y Funcional de Algunas Frutas de La Amazonía Ecuatoriana; Estación Experimental Santa Catalina: Quito, Ecuador, 2008.

- Vargas, V.; Clement, C.; Moraes, M. Bactris Gasipaes (Arecaceae): Una Palmera Con Larga Historia de Aprovechamiento y Selección En Sud América. In Palmeras y usos: Especies de Bolivia y la Región; Moraes, M., Ed.; Universidad Mayor de San: La Paz, Bolivia, 2020; pp. 37–46. ISBN 978-99954-1-969-1.

- Arunachalam, V. Peach Palm. In Genomics of Cultivated Palms; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 75–80. ISBN 978-0-12-387736-9.

- Pirovani, D.B.; Pezzopane, J.E.M.; Xavier, A.C.; Pezzopane, J.R.M.; de Jesus Júnior, W.C.; Machuca, M.A.H.; dos Santos, G.M.A.D.A.; da Silva, S.F.; de Almeida, S.L.H.; de Oliveira Peluzio, T.M.; et al. Climate Change Impacts on the Aptitude Area of Forest Species. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 95, 405–416.

- Bush, M.B.; Nascimento, M.N.; Åkesson, C.M.; Cárdenes-Sandí, G.M.; Maezumi, S.Y.; Behling, H.; Correa-Metrio, A.; Church, W.; Huisman, S.N.; Kelly, T.; et al. Widespread Reforestation before European Influence on Amazonia. Science 2021, 372, 484–487.

- Graefe, S.; Dufour, D.; van Zonneveld, M.; Rodriguez, F.; Gonzalez, A. Peach Palm (Bactris Gasipaes) in Tropical Latin America: Implications for Biodiversity Conservation, Natural Resource Management and Human Nutrition. Biodivers. Conserv. 2013, 22, 269–300.

- da Costa, R.D.S.; da Rodrigues, A.M.C.; da Silva, L.H.M. The Fruit of Peach Palm (Bactris Gasipaes) and Its Technological Potential: An Overview. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 42, e82721.

- Henderson, A. Bactris (Palmae). Flora Neotrop. 2000, 79, 1–181.

- Govaerts, R.; Dransfield, J. World Checklist of Palms; Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew: Richmond, UK, 2005; ISBN 978-1-84246-084-9.

- Buitrago Acosta, M.C.; Montúfar, R.; Guyot, R.; Mariac, C.; Tranbarger, T.J.; Restrepo, S.; Couvreur, T.L.P. Bactris Gasipaes Kunth Var. Gasipaes Complete Plastome and Phylogenetic Analysis. Mitochondrial DNA Part B 2022, 7, 1540–1544.

- Clement, C.; Araújo, M.; Coppens d’Eeckenbrugge, G.; dos Reis, V.; Lehnebach, R.; Picanço, D. Origin and Dispersal of Domesticated Peach Palm. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 5, 1–19.

- Lim, T.K. Bactris Gasipaes. In Edible Medicinal and Non-Medicinal Plants: Volumen 6, Fruits; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012; Volume 1, pp. 285–292.

- Lehmann, H.; Gutmann, O.; Lasso, M.; Mayo, R.; Ponce, T.; Caicamo, O.; Silva, V.; Perez, N.; Riascos, G.; Muñoz, M.; et al. Dramatic Fruit Fall of Peach Palm in Subsistence Agriculture in Colombia: Epidemiology, Cause and Control. In Proceedings of the TROPENTAG 2013, Stuttgart, Germany, 17–19 September 2013; University of Hohenheim: Stuttgart, Germany, 2013; pp. 1–11.

- Joas, J.; Le Blanc, M.; Beaumont, C.; Michels, T. Physico-Chemical Analyses, Sensory Evaluation and Potential of Minimal Processing of Pejibaye (Bactris Gasipaes) Compared to Mascarenes Palms. J. Food Qual. 2010, 33, 216–229.

- Paniagua-Zambrana, N.Y.; Bussmann, R.W.; Romero, C. Bactris Gasipaes Kunth. In Ethnobotany of the Andes; Paniagua-Zambrana, N.Y., Bussmann, R.W., Eds.; Ethnobotany of Mountain Regions; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–17. ISBN 978-3-319-77093-2.

- Paniagua, N.; Bussmann, R.; Romero, C. Bactris Gasipaes Kunth; Paniagua, N., Bussmann, R., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2020.

- Gutiérrez, C.; Peralta, R. Palmas Comunes de Pando; Editora El País; Proyecto de Manejo Forestal Sostenible de Pando: Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Bolivia, 2001.

- Ribeiro, S.A.; Coneglian, R.C.C.; Silva, B.C.; Deco, T.A.; Prudêncio, E.R.; Dias, A. Shelf Life Extension of Peach Palm Heart Packed in Different Plastic Packages. Hortic. Bras. 2021, 39, 26–31.

- Stevanato, N.; Ribeiro, T.H.; Giombelli, C.; Cardoso, T.; Wojeicchowski, J.P.; Godoy, E.D.; Bolanho, B. Effect of Canning on the Antioxidant Activity, Fiber Content, and Mechanical Properties of Different Parts of Peach Palm Heart. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2020, 44, 1–8.

- Theilkuhl, S. Chontaduro Bactris Gasipaes (Kunth); Agricultural Science; Colegio Bolívar: Cali, Colombia, 2018.

- dos Santos, O.V.; Soares, S.D.; Dias, P.C.S.; das Chagas Alves do Nascimento, F.; Vieira da Conceição, L.R.; da Costa, R.S.; da Silva Pena, R. White Peach Palm (Pupunha) a New Bactris Gasipaes Kunt Variety from the Amazon: Nutritional Composition, Bioactive Lipid Profile, Thermogravimetric and Morphological Characteristics. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2022, 112, 104684.

- Chisté, R.C.; Costa, E.L.N.; Monteiro, S.F.; Mercadante, A.Z. Carotenoid and Phenolic Compound Profiles of Cooked Pulps of Orange and Yellow Peach Palm Fruits (Bactris Gasipaes) from the Brazilian Amazonia. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2021, 99, 103873.

- Galluzzi, G.; Dufour, D.; Thomas, E.; van Zonneveld, M.; Escobar Salamanca, A.F.; Giraldo Toro, A.; Rivera, A.; Salazar Duque, H.; Suárez Baron, H.; Gallego, G.; et al. An Integrated Hypothesis on the Domestication of Bactris Gasipaes. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0144644.

- Cárdenas, D.; Marín, N.; Castaño, N. Plantas Alimenticias No Convencionales En La Amazonía Colombiana y Anotaciones Sobre Otras Plantas Alimenticias. Rev. Colomb. Amaz. 2012, 5, 58–81.

- Vargas, V.; Moraes R., M.; Roncal, J. Fruit Morphology and Yield of Bactris Gasipaes in Tumupasa, Bolivia. Palms 2018, 62, 17–24.

- Haro, E.E.; Szpunar, J.A.; Odeshi, A.G. Dynamic and Ballistic Impact Behavior of Biocomposite Armors Made of HDPE Reinforced with Chonta Palm Wood (Bactris Gasipaes) Microparticles. Def. Technol. 2018, 14, 238–249.

- da Silva, J.; Clement, C. Wild Pejibaye (Bactris Gasipaes Kunth Var. Chichagui) in Southeastern Amazonía. Acta Botánica Bras. 2005, 19, 281–284.

- Sosnowska, J.; Kujawska, M. All Useful Plants Have Not Only Identities, but Stories: The Mythical Origins of the Peach Palm (Bactris Gasipaes Kunth) According to the Peruvian Asháninka. Trames J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2014, 18, 173.

- Herrera Angel, L. Kanuma: Un Mito de Los Yukuna Matapí. Rev. Colomb. Antropol. 1975, 18, 285–416.

- Nantipia, J.E.; La Sánchez, F. Celebración del rito de Uwi en el pueblo Shuar-Achuar (Fiesta de la Chonta). In La Fiesta Religiosa Indigena en el Ecuador: Pueblos indigenas y educación; Abya Yala: Quito, Ecuador, 1995; ISBN 9978-04-159-1.

- Villa Posse, E. (Ed.) Mitos y Leyendas de Colombia: Selección de Textos, 1st ed.; Colección “Integración cultural”; Ediciones IADAP: Quito, Ecuador, 1991; ISBN 978-9978-60-004-7.

- Nakashima, D.; Krupnik, I.; Rubis, J.T. (Eds.) Indigenous Knowledge for Climate Change Assessment and Adaptation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2018; ISBN 978-1-107-13788-2.

- Yucci, T.E.V.; León, P.; Torres, D. Fiesta de la chonta y su impacto en el turismo comunitario del pueblo shuar. Kill. Soc. 2017, 1, 9–14.

- Mora-Urpí, J. Pejibaye (Bactris gasipaes). In Cultivos Marginados: Otra Perspectiva de 1492; Hernández Bermejo, J.E., León, J., Eds.; Producción y Protección Vegetal; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1992; ISBN 978-92-5-303217-4.

- Mora-Urpi, J.; Weber, J.C.; Clement, C.R. Peach Palm: Bactris Gasipaes Kunth; Promoting the Conservation and Use of Underutilized and Neglected Crops; IPK: Rome, Italy; IPGRI: Rome, Italy, 1997; ISBN 978-92-9043-347-7.

- Patiño, V.M. Historia Colonial y Nombres Indígenas de La Palma Pijibay (Guilielma Gasipaes (HBK) Bailey). Rev. Colomb. Antropol. 1960, 9, 25–72.

- Prance, G.; Nesbitt, M. The Cultural History of Plants; Routledge: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2005; ISBN 978-0-415-92746-8.

- Popenoe, W.; Jimenez, O. The Pejibaye a Neglected Food-Plant of Tropical America. J. Hered. 1921, 12, 154–166.

- Patiño, V.M. Historia y Dispersión de los Frutales Nativos del Neotrópico; CIAT: London, UK, 2002; ISBN 978-958-694-037-5.

More

Information

Subjects:

Food Science & Technology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.4K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

24 Nov 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No