| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nikos E. Papaioannou | -- | 2590 | 2022-11-23 10:07:56 | | | |

| 2 | Lindsay Dong | -2 word(s) | 2588 | 2022-11-24 14:07:16 | | | | |

| 3 | Lindsay Dong | Meta information modification | 2588 | 2022-11-24 14:08:02 | | |

Video Upload Options

Immune-mediated inflammatory diseases (IMIDs) are a group of autoimmune and chronic inflammatory disorders with constantly increasing prevalence in the modern world. The vast majority of IMIDs develop as a consequence of complex mechanisms dependent on genetic, epigenetic, molecular, cellular, and environmental elements, that lead to defects in immune regulatory guardians of tolerance, such as dendritic (DCs) cells.

1. Introduction

2. Dendritic Cells as Multifaceted Orchestrators of Immune Responses

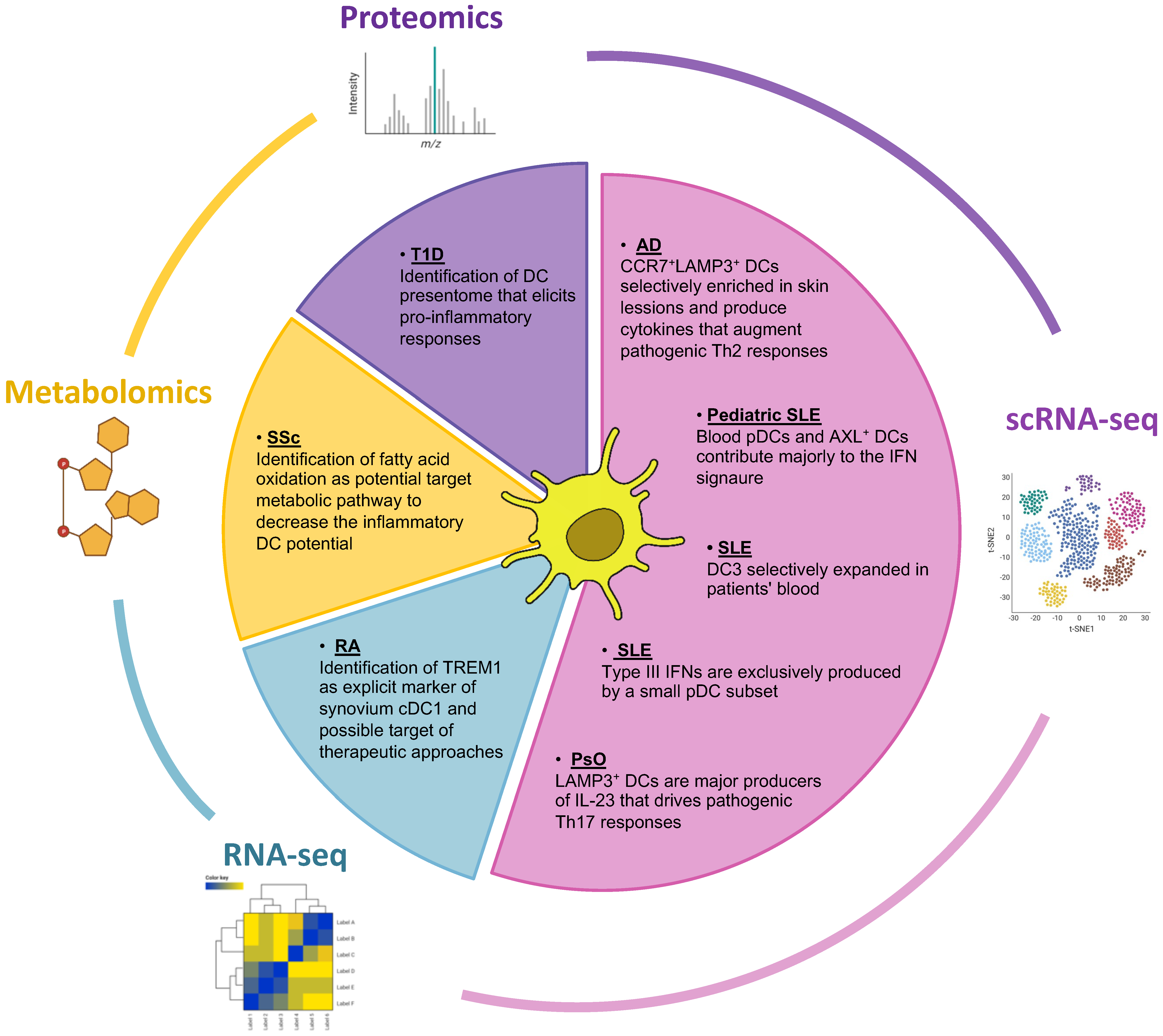

The multifaceted role of DCs in immune responses is a derivative of their heterogeneity. Notably, the DC term functions as an umbrella that encloses several cell subsets, each possessing distinct developmental requirements, phenotype and functional properties [11][12]. While DCs have initially been studied more extensively in mice, with the help of multi-omics approaches, recent publications have elegantly dissected the human DC compartment, elucidating in parallel a high interspecies conservation of their development, phenotype and function [12][13][14]. Among DCs, two main distinct lineages can be distinguished, namely conventional DCs (cDCs) and plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs).

2.1. Elucidating the Role of Dendritic Cells in IMIDs Utilizing Multi-Omics Approaches

2.2. Bulk and Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Have Expanded the Portfolio of DC Subsets and Illuminated Their Role in IMIDs Perturbations

2.3. Contribution of Proteomics in the Identification of DC-Presented Epitopes in IMIDs

2.4. Bridging the Metabolic Profile and the Function of DCs in IMIDs: An Emerging Field of Research

References

- Wahren-Herlenius, M.; Dörner, T. Immunopathogenic Mechanisms of Systemic Autoimmune Disease. Lancet 2013, 382, 819–831.

- Bluestone, J.A.; Anderson, M. Tolerance in the Age of Immunotherapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1156–1166.

- Steinman, R.M.; Hemmi, H. Dendritic Cells: Translating Innate to Adaptive Immunity. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2006, 311, 17–58.

- Mellman, I.; Steinman, R.M. Dendritic Cells Specialized and Regulated Antigen Processing Machines. Cell 2001, 106, 255–258.

- Sakaguchi, S.; Yamaguchi, T.; Nomura, T.; Ono, M. Regulatory T Cells and Immune Tolerance. Cell 2008, 133, 775–787.

- Fontenot, J.D.; Gavin, M.A.; Rudensky, A.Y. Foxp3 Programs the Development and Function of CD4+CD25+ Regulatory T Cells. Nat. Immunol. 2003, 4, 330–336.

- Coutant, F.; Miossec, P. Altered Dendritic Cell Functions in Autoimmune Diseases: Distinct and Overlapping Profiles. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2016, 12, 703–715.

- Sakaguchi, S.; Mikami, N.; Wing, J.B.; Tanaka, A.; Ichiyama, K.; Ohkura, N. Regulatory T Cells and Human Disease. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 38, 541–566.

- Dominguez-Villar, M.; Hafler, D.A. Regulatory T Cells in Autoimmune Disease. Nat. Immunol. 2018, 19, 665–673.

- Hatzioannou, A.; Boumpas, A.; Papadopoulou, M.; Papafragkos, I.; Varveri, A.; Alissafi, T.; Verginis, P. Regulatory T Cells in Autoimmunity and Cancer: A Duplicitous Lifestyle. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 731947.

- Durai, V.; Murphy, K.M. Functions of Murine Dendritic Cells. Immunity 2016, 45, 719–736.

- Cabeza-Cabrerizo, M.; Cardoso, A.; Minutti, C.M.; da Costa, M.P.; Reis e Sousa, C. Dendritic Cells Revisited. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2021, 39, 131–166.

- Guilliams, M.; Dutertre, C.-A.; Scott, C.L.; McGovern, N.; Sichien, D.; Chakarov, S.; Gassen, S.V.; Chen, J.; Poidinger, M.; Prijck, S.D.; et al. Unsupervised High-Dimensional Analysis Aligns Dendritic Cells across Tissues and Species. Immunity 2016, 45, 669–684.

- Patente, T.A.; Pinho, M.P.; Oliveira, A.A.; Evangelista, G.C.M.; Bergami-Santos, P.C.; Barbuto, J.A.M. Human Dendritic Cells: Their Heterogeneity and Clinical Application Potential in Cancer Immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2019, 9, 3176.

- Reizis, B. Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells: Development, Regulation, and Function. Immunity 2019, 50, 37–50.

- See, P.; Dutertre, C.-A.; Chen, J.; Günther, P.; McGovern, N.; Irac, S.E.; Gunawan, M.; Beyer, M.; Händler, K.; Duan, K.; et al. Mapping the Human DC Lineage through the Integration of High-Dimensional Techniques. Science 2017, 356, eaag3009.

- Matsui, T.; Connolly, J.E.; Michnevitz, M.; Chaussabel, D.; Yu, C.I.; Glaser, C.; Tindle, S.; Pypaert, M.; Freitas, H.; Piqueras, B.; et al. CD2 Distinguishes Two Subsets of Human Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells with Distinct Phenotype and Functions. J. Immunol. 2009, 182, 6815.

- Villadangos, J.A.; Young, L. Antigen-Presentation Properties of Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells. Immunity 2008, 29, 352–361.

- Hoeffel, G.; Ripoche, A.C.; Matheoud, D.; Nascimbeni, M.; Escriou, N.; Lebon, P.; Heshmati, F.; Guillet, J.G.; Gannagé, M.; Caillat-Zucman, S.; et al. Antigen Crosspresentation by Human Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells. Immunity 2007, 27, 481–492.

- Rodrigues, P.F.; Alberti-Servera, L.; Eremin, A.; Grajales-Reyes, G.E.; Ivanek, R.; Tussiwand, R. Distinct Progenitor Lineages Contribute to the Heterogeneity of Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells. Nat. Immunol. 2018, 19, 711–722.

- Dress, R.J.; Dutertre, C.-A.; Giladi, A.; Schlitzer, A.; Low, I.; Shadan, N.B.; Tay, A.; Lum, J.; Kairi, M.F.B.M.; Hwang, Y.Y.; et al. Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells Develop from Ly6D+ Lymphoid Progenitors Distinct from the Myeloid Lineage. Nat. Immunol. 2019, 20, 852–864.

- Feng, J.; Pucella, J.N.; Jang, G.; Alcántara-Hernández, M.; Upadhaya, S.; Adams, N.M.; Khodadadi-Jamayran, A.; Lau, C.M.; Stoeckius, M.; Hao, S.; et al. Clonal Lineage Tracing Reveals Shared Origin of Conventional and Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells. Immunity 2022, 55, 405–422.e11.

- Mair, F.; Liechti, T. Comprehensive Phenotyping of Human Dendritic Cells and Monocytes. Cytom. Part A 2021, 99, 231–242.

- Poulin, L.F.; Reyal, Y.; Uronen-Hansson, H.; Schraml, B.U.; Sancho, D.; Murphy, K.M.; Hakansson, U.K.; Moita, L.F.; Agace, W.W.; Bonnet, D.; et al. DNGR-1 Is a Specific and Universal Marker of Mouse and Human Batf3-Dependent Dendritic Cells in Lymphoid and Nonlymphoid Tissues. Blood 2012, 119, 6052–6062.

- Sichien, D.; Scott, C.L.; Martens, L.; Vanderkerken, M.; Gassen, S.V.; Plantinga, M.; Joeris, T.; Prijck, S.D.; Vanhoutte, L.; Vanheerswynghels, M.; et al. IRF8 Transcription Factor Controls Survival and Function of Terminally Differentiated Conventional and Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells, Respectively. Immunity 2016, 45, 626–640.

- Hildner, K.; Edelson, B.T.; Purtha, W.E.; Diamond, M.; Matsushita, H.; Kohyama, M.; Calderon, B.; Schraml, B.U.; Unanue, E.R.; Diamond, M.S.; et al. Batf3 Deficiency Reveals a Critical Role for CD8α+ Dendritic Cells in Cytotoxic T Cell Immunity. Science 2008, 322, 1097–1100.

- Hacker, C.; Kirsch, R.D.; Ju, X.S.; Hieronymus, T.; Gust, T.C.; Kuhl, C.; Jorgas, T.; Kurz, S.M.; Rose-John, S.; Yokota, Y.; et al. Transcriptional Profiling Identifies Id2 Function in Dendritic Cell Development. Nat. Immunol. 2003, 4, 380–386.

- Kashiwada, M.; Pham, N.L.; Pewe, L.L.; Harty, J.T.; Rothman, P.B. NFIL3/E4BP4 Is a Key Transcription Factor for CD8α+ Dendritic Cell Development. Blood 2011, 117, 6193–6197.

- Liu, T.-T.; Kim, S.; Desai, P.; Kim, D.-H.; Huang, X.; Ferris, S.T.; Wu, R.; Ou, F.; Egawa, T.; Dyken, S.J.V.; et al. Ablation of cDC2 Development by Triple Mutations within the Zeb2 Enhancer. Nature 2022, 607, 142–148.

- Reis e Sousa, C.; Hieny, S.; Scharton-Kersten, T.; Jankovic, D.; Charest, H.; Germain, R.N.; Sher, A. In Vivo Microbial Stimulation Induces Rapid CD40 Ligand-Independent Production of Interleukin 12 by Dendritic Cells and Their Redistribution to T Cell Areas. J. Exp. Med. 1997, 186, 1819–1829.

- Mashayekhi, M.; Sandau, M.M.; Dunay, I.R.; Frickel, E.M.; Khan, A.; Goldszmid, R.S.; Sher, A.; Ploegh, H.L.; Murphy, T.L.; Sibley, L.D.; et al. CD8α+ Dendritic Cells Are the Critical Source of Interleukin-12 That Controls Acute Infection by Toxoplasma Gondii Tachyzoites. Immunity 2011, 35, 249–259.

- Idoyaga, J.; Fiorese, C.; Zbytnuik, L.; Lubkin, A.; Miller, J.; Malissen, B.; Mucida, D.; Merad, M.; Steinman, R.M. Specialized Role of Migratory Dendritic Cells in Peripheral Tolerance Induction. J. Clin. Investig. 2013, 123, 844–854.

- Tabansky, I.; Keskin, D.B.; Watts, D.; Petzold, C.; Funaro, M.; Sands, W.; Wright, P.; Yunis, E.J.; Najjar, S.; Diamond, B.; et al. Targeting DEC-205-DCIR2+ Dendritic Cells Promotes Immunological Tolerance in Proteolipid Protein-Induced Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis. Mol. Med. 2018, 24, 17.

- Bosteels, C.; Scott, C.L. Transcriptional Regulation of DC Fate Specification. Mol. Immunol. 2020, 121, 38–46.

- Dudziak, D.; Kamphorst, A.O.; Heidkamp, G.F.; Buchholz, V.R.; Trumpfheller, C.; Yamazaki, S.; Cheong, C.; Liu, K.; Lee, H.W.; Park, C.G.; et al. Differential Antigen Processing by Dendritic Cell Subsets in Vivo. Science 2007, 315, 107–111.

- Shin, C.; Han, J.-A.; Choi, B.; Cho, Y.-K.; Do, Y.; Ryu, S. Intrinsic Features of the CD8α− Dendritic Cell Subset in Inducing Functional T Follicular Helper Cells. Immunol. Lett. 2016, 172, 21–28.

- Persson, E.K.; Uronen-Hansson, H.; Semmrich, M.; Rivollier, A.; Hägerbrand, K.; Marsal, J.; Gudjonsson, S.; Håkansson, U.; Reizis, B.; Kotarsky, K.; et al. IRF4 Transcription-Factor-Dependent CD103+CD11b+ Dendritic Cells Drive Mucosal T Helper 17 Cell Differentiation. Immunity 2013, 38, 958–969.

- Schlitzer, A.; McGovern, N.; Teo, P.; Zelante, T.; Atarashi, K.; Low, D.; Ho, A.W.S.; See, P.; Shin, A.; Wasan, P.S.; et al. IRF4 Transcription Factor-Dependent CD11b+ Dendritic Cells in Human and Mouse Control Mucosal IL-17 Cytokine Responses. Immunity 2013, 38, 970–983.

- Tussiwand, R.; Everts, B.; Grajales-Reyes, G.E.; Kretzer, N.M.; Iwata, A.; Bagaitkar, J.; Wu, X.; Wong, R.; Anderson, D.A.; Murphy, T.L.; et al. Klf4 Expression in Conventional Dendritic Cells Is Required for T Helper 2 Cell Responses. Immunity 2015, 42, 916–928.

- Rojas, I.M.L.; Mok, W.-H.; Pearson, F.E.; Minoda, Y.; Kenna, T.J.; Barnard, R.T.; Radford, K.J. Human Blood CD1c+ Dendritic Cells Promote Th1 and Th17 Effector Function in Memory CD4+ T Cells. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 971.

- Binnewies, M.; Mujal, A.M.; Pollack, J.L.; Combes, A.J.; Hardison, E.A.; Barry, K.C.; Tsui, J.; Ruhland, M.K.; Kersten, K.; Abushawish, M.A.; et al. Unleashing Type-2 Dendritic Cells to Drive Protective Antitumor CD4+ T Cell Immunity. Cell 2019, 177, 556–571.e16.

- Mayer, J.U.; Hilligan, K.L.; Chandler, J.S.; Eccles, D.A.; Old, S.I.; Domingues, R.G.; Yang, J.; Webb, G.R.; Munoz-Erazo, L.; Hyde, E.J.; et al. Homeostatic IL-13 in Healthy Skin Directs Dendritic Cell Differentiation to Promote TH2 and Inhibit TH17 Cell Polarization. Nat. Immunol. 2021, 22, 1538–1550.

- Bamboat, Z.M.; Stableford, J.A.; Plitas, G.; Burt, B.M.; Nguyen, H.M.; Welles, A.P.; Gonen, M.; Young, J.W.; DeMatteo, R.P. Human Liver Dendritic Cells Promote T Cell Hyporesponsiveness. J. Immunol. 2009, 182, 1901.

- Hu, Z.; Li, Y.; Nieuwenhuijze, A.V.; Selden, H.J.; Jarrett, A.M.; Sorace, A.G.; Yankeelov, T.E.; Liston, A.; Ehrlich, L.I.R. CCR7 Modulates the Generation of Thymic Regulatory T Cells by Altering the Composition of the Thymic Dendritic Cell Compartment. Cell Rep. 2017, 21, 168–180.

- Brown, C.C.; Gudjonson, H.; Pritykin, Y.; Deep, D.; Lavallée, V.-P.; Mendoza, A.; Fromme, R.; Mazutis, L.; Ariyan, C.; Leslie, C.; et al. Transcriptional Basis of Mouse and Human Dendritic Cell Heterogeneity. Cell 2019, 179, 846–863.e24.

- Lewis, K.L.; Caton, M.L.; Bogunovic, M.; Greter, M.; Grajkowska, L.T.; Ng, D.; Klinakis, A.; Charo, I.F.; Jung, S.; Gommerman, J.L.; et al. Notch2 Receptor Signaling Controls Functional Differentiation of Dendritic Cells in the Spleen and Intestine. Immunity 2011, 35, 780–791.

- Bosteels, C.; Neyt, K.; Vanheerswynghels, M.; Helden, M.J.V.; Sichien, D.; Debeuf, N.; Prijck, S.D.; Bosteels, V.; Vandamme, N.; Martens, L.; et al. Inflammatory Type 2 cDCs Acquire Features of cDC1s and Macrophages to Orchestrate Immunity to Respiratory Virus Infection. Immunity 2020, 52, 1039–1056.e9.

- Villani, A.-C.; Satija, R.; Reynolds, G.; Sarkizova, S.; Shekhar, K.; Fletcher, J.; Griesbeck, M.; Butler, A.; Zheng, S.; Lazo, S.; et al. Single-Cell RNA-Seq Reveals New Types of Human Blood Dendritic Cells, Monocytes, and Progenitors. Science 2017, 356, eaah4573.

- Dutertre, C.-A.; Becht, E.; Irac, S.E.; Khalilnezhad, A.; Narang, V.; Khalilnezhad, S.; Ng, P.Y.; van den Hoogen, L.L.; Leong, J.Y.; Lee, B.; et al. Single-Cell Analysis of Human Mononuclear Phagocytes Reveals Subset-Defining Markers and Identifies Circulating Inflammatory Dendritic Cells. Immunity 2019, 51, 573–589.e8.

- Bourdely, P.; Anselmi, G.; Vaivode, K.; Ramos, R.N.; Missolo-Koussou, Y.; Hidalgo, S.; Tosselo, J.; Nuñez, N.; Richer, W.; Vincent-Salomon, A.; et al. Transcriptional and Functional Analysis of CD1c+ Human Dendritic Cells Identifies a CD163+ Subset Priming CD8+CD103+ T Cells. Immunity 2020, 53, 335–352.e8.

- Nehar-Belaid, D.; Hong, S.; Marches, R.; Chen, G.; Bolisetty, M.; Baisch, J.; Walters, L.; Punaro, M.; Rossi, R.J.; Chung, C.-H.; et al. Mapping Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Heterogeneity at the Single-Cell Level. Nat. Immunol. 2020, 21, 1094–1106.

- Liu, K.; Victora, G.D.; Schwickert, T.A.; Guermonprez, P.; Meredith, M.M.; Yao, K.; Chu, F.-F.; Randolph, G.J.; Rudensky, A.Y.; Nussenzweig, M. In Vivo Analysis of Dendritic Cell Development and Homeostasis. Science 2009, 324, 392–397.

- Granot, T.; Senda, T.; Carpenter, D.J.; Matsuoka, N.; Weiner, J.; Gordon, C.L.; Miron, M.; Kumar, B.V.; Griesemer, A.; Ho, S.-H.; et al. Dendritic Cells Display Subset and Tissue-Specific Maturation Dynamics over Human Life. Immunity 2017, 46, 504–515.

- Canavan, M.; Walsh, A.M.; Bhargava, V.; Wade, S.M.; McGarry, T.; Marzaioli, V.; Moran, B.; Biniecka, M.; Convery, H.; Wade, S.; et al. Enriched Cd141+ DCs in the Joint Are Transcriptionally Distinct, Activated, and Contribute to Joint Pathogenesis. JCI Insight 2018, 3, e95228.

- Canavan, M.; Marzaioli, V.; McGarry, T.; Bhargava, V.; Nagpal, S.; Veale, D.J.; Fearon, U. Rheumatoid Arthritis Synovial Microenvironment Induces Metabolic and Functional Adaptations in Dendritic Cells. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2020, 202, 226–238.

- He, H.; Suryawanshi, H.; Morozov, P.; Gay-Mimbrera, J.; Duca, E.D.; Kim, H.J.; Kameyama, N.; Estrada, Y.; Der, E.; Krueger, J.G.; et al. Single-Cell Transcriptome Analysis of Human Skin Identifies Novel Fibroblast Subpopulation and Enrichment of Immune Subsets in Atopic Dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immun. 2020, 145, 1615–1628.

- Rojahn, T.B.; Vorstandlechner, V.; Krausgruber, T.; Bauer, W.M.; Alkon, N.; Bangert, C.; Thaler, F.M.; Sadeghyar, F.; Fortelny, N.; Gernedl, V.; et al. Single-Cell Transcriptomics Combined with Interstitial Fluid Proteomics Defines Cell Type–Specific Immune Regulation in Atopic Dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immun. 2020, 146, 1056–1069.

- Van Lummel, M.; van Veelen, P.A.; de Ru, A.H.; Janssen, G.M.C.; Pool, J.; Laban, S.; Joosten, A.M.; Nikolic, T.; Drijfhout, J.W.; Mearin, M.L.; et al. Dendritic Cells Guide Islet Autoimmunity through a Restricted and Uniquely Processed Peptidome Presented by High-Risk HLA-DR. J. Immunol. 2016, 196, 3253–3263.

- Ottria, A.; Hoekstra, A.T.; Zimmermann, M.; van der Kroef, M.; Vazirpanah, N.; Cossu, M.; Chouri, E.; Rossato, M.; Beretta, L.; Tieland, R.G.; et al. Fatty Acid and Carnitine Metabolism Are Dysregulated in Systemic Sclerosis Patients. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 822.