| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sirius Huang | -- | 2102 | 2022-11-22 01:31:21 |

Video Upload Options

The quadruple along with the quintuple innovation helix framework was co-developed by Elias G. Carayannis and David F.J. Campbell, with the quadruple helix being described in a 2009 article and the quintuple helix in a 2010 article. It extends and expands substantially the triple helix model of innovation economics as the framework introduces civil society and the environment as pillars and focal points of policy and practice. In particular, civil society emphasizes the role of bottom-up initiatives complementing top-down government, university and industry policies and practices, and the environment emphasizes the sustainability priorities and exigencies that need to inform and moderate top-down policies and practices as well as bottom-up initiatives. Within the quintuple helix, these represent the sine qua non of smart, sustainable and inclusive growth. The quintuple helix views the natural environments of society and the economy as drivers for knowledge production and innovation, thus defining opportunities for the knowledge society and knowledge economy. The quintuple helix can be described in terms of the models of knowledge that it extends, the five subsystems (helices) it incorporates, and the steps involved in the circulation of knowledge. How to define these new helices has been debated and some researchers see them as additional helices while some see them as different types of helix which overarch the previous helices.

1. Definition

The quintuple helix model is based on the triple and quadruple helix models and adds as fifth helix the natural environment, “where the environment or the natural environments represent the fifth helix”: “The Quintuple Helix can be proposed as a framework for transdisciplinary (and interdisciplinary) analysis of sustainable development and social ecology”.[1]

2. Models of Knowledge

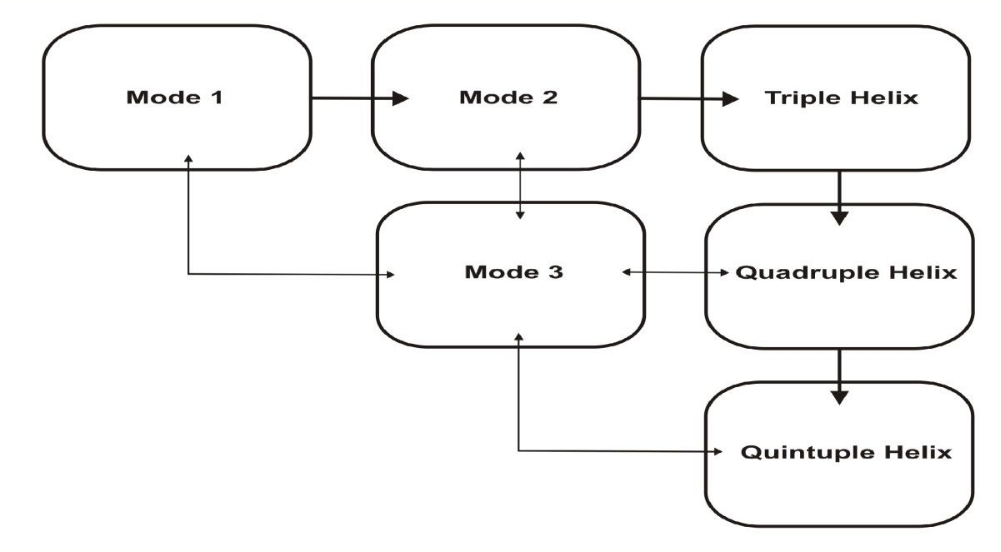

The quintuple helix can be seen as the logical extension of previous models of knowledge, specifically mode 1, mode 2, the triple helix, mode 3, and the quadruple helix.

These are summarized as:

Mode 1.[2] Mode 1 was theorized by Michael Gibbons and “focuses on the traditional role of university research in an elderly ‘linear model of innovation’ understanding”, and success in mode 1 “is defined as a quality or excellence that is approved by hierarchically established peers”.[3]

Mode 2.[4] Mode 2 was theorized by Michael Gibbons and is characterized by the following five principles: (1) knowledge produced in the context of application; (2) transdisciplinarity; (3) heterogeneity and organizational diversity; (4) social accountability and reflexivity; (5) and quality control.[5]

Triple Helix.[6] The triple helix was first suggested by Henry Etzkowitz and Loet Leydesdorff in 1995.[7] The “Triple Helix overlay provides a model at the level of social structure for the explanation of mode 2 as an historically emerging structure for the production of scientific knowledge, and its relation to Mode 1,”[8] and it is a “model of ‘trilateral networks and hybrid organizations’ of ‘university-industry-government relations’”.[9]

Mode 3.[10] Mode 3 was developed by Elias G. Carayannis and David F.J. Campbell in 2006. “The concept of mode 3 is more inclined to emphasize the coexistence and coevolution of different knowledge and innovation modes. Mode 3 even accentuates such pluralism and diversity of knowledge and innovation modes as being necessary for advancing societies and economies. This pluralism supports the processes of a mutual cross-learning from the different knowledge modes”.[11] Mode 3 “encourages interdisciplinary thinking and transdisciplinary application of interdisciplinary knowledge” and “allows and emphasizes the coexistence and coevolution of different knowledge and innovation paradigms.’”[12]

The quadruple helix. Building on the triple helix model of innovation economics, the quadruple helix model adds a fourth component to the framework of interactions between university, industry and government: civil society and the media.[13] This was first suggested in 2009 by Elias G. Carayannis and David F.J. Campbell in "‘Mode 3’ and ‘Quadruple Helix’: toward a 21st century fractal innovation ecosystem";[14] various authors were exploring the concept of a user-oriented quadruple helix extension to the triple helix model of innovation around the same time.[15][16][17] The aim is to bridge the gaps between innovation and users in the form of civil society. Indeed, this framework claims that under the triple helix model, emerging technologies do not always match the demands and needs of society, thus limiting their potential impact. This framework emphasizes a societal responsibility of universities, in addition to their role of educating and conduction research. The quadruple helix model also incorporates the concept of a 'media-based democracy',[18] which Carayannis and Campbell, following Plasser, define as "media reality overlaps with political and social reality; perception of politics primarily through the media; and the laws of the media system determining political actions and strategies."[19] Carayannis and Campbell state this fourth helix includes both the civil society and the users of innovation, thereby acknowledging that knowledge and innovation policies and strategies must incorporate the ‘public’ to successfully achieve goals and objectives. In the quadruple helix, public reality is constantly being constructed and communicated via the media, while also being influenced by culture and values through cultural artefacts like movies. When the political system (government) is developing innovation policy to develop the economy, it must adequately communicate its innovation policy with the public via the media "to seek legitimation and justification,"[20] i.e., public support for new strategies or policies. For industry involved in R&D, companies' public relations strategies have to negotiate ‘reality construction’ by the media.[21] For university and academia, Carayannis and Campbell offer the example of improving the gender ratio in engineering courses by improving the ‘social images’ of women and technology in society[22] in order to improve the "innovation cultures"[23] involved. How to define this fourth helix has been debated according to Högluind and Linton (2018),[24] and some researchers see it as an additional helix while others see it as a different type of helix which is overarching all the other helices.[25] The quadruple helix has implications for smart co-evolution of regional innovation and institutional arrangements, i.e., regional innovation systems.[26][27][28] As such, the quadruple helix is the approach that the European Union has intended to take for the development of a competitive knowledge-based society.[29] The quadruple helix has been applied to European Union-sponsored projects and policies, including the EU-MACS (EUropean MArket for Climate Services) project,[30] a follow-up project of the European Research and Innovation Roadmap for Climate Services, and the European Commission's Open Innovation 2.0 (OI2) policy for a digital single market that supports open innovation.[31] It has also been applied to OECD countries.[32]

3. The Five Helices

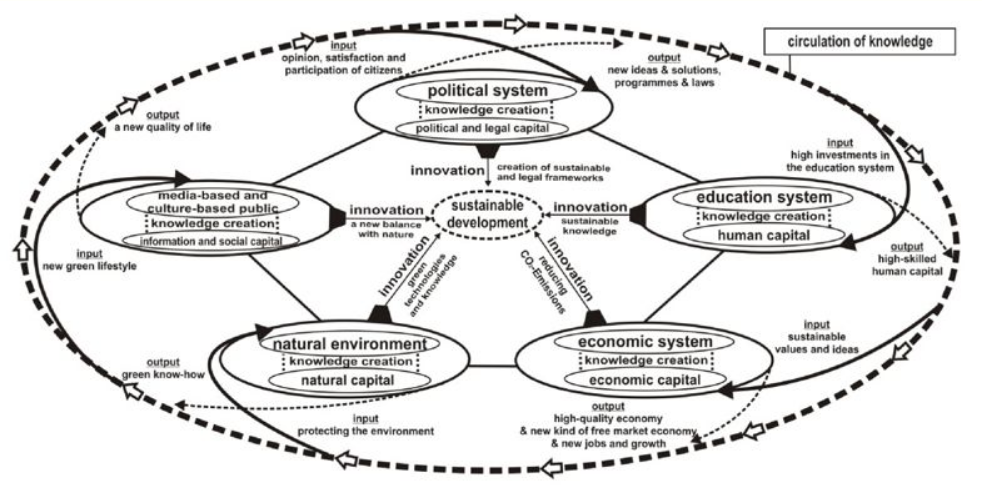

Apart from active human agents, the most important constituent element of the quintuple helix is knowledge, which, through a circulation between societal subsystems, changes to innovation and know-how in a society and for the economy.[33] The quintuple helix visualizes the collective interaction and exchange of this knowledge in a state by means of the following five subsystems (i.e., helices): (1) education system, (2) economic system, (3) natural environment, (4) media-based and culture-based public (also ‘civil society’), (5) and the political system.[34] Each of the five helices has an asset at its disposal, with a societal and scientific relevance.

1) The education system defines itself in reference to academia, universities, higher education systems, and schools. In this helix, the necessary ‘human capital’ (e.g., students, teachers, scientists/ researchers, academic entrepreneurs, etc.) of a state is being formed by diffusion and research of knowledge.

2) The economic system consists of industry/industries, firms, services and banks. This helix concentrates and focuses the economic capital (e.g., entrepreneurship, machines, products, technology, money, etc.) of a state.

3) The natural environment subsystem is decisive for sustainable development and provides people with natural capital (e.g., resources, plants, variety of animals, etc.).

4) The media-based and culture-based public subsystem integrates and combines two forms of capital. This helix has, through the culture-based public (e.g., traditions, values, etc.), a social capital. In addition, the helix of media-based public (e.g., television, internet, newspapers, etc.) contains capital of information (e.g., news, communication, social networks).

5) The political system formulates the will, i.e., where the state is heading, thereby also defining, organizing, and administering the general conditions of the state. Therefore, this helix has political and legal capital (e.g., ideas, laws, plans, politicians, etc.).

4. Circulation of Knowledge

The resource of knowledge is the most important ‘commodity’ in the quintuple helix, and the circulation of knowledge continually stimulates new knowledge. Consequently, all helices in the quintuple helix influence each other with knowledge in order to promote sustainability through new, advanced and pioneering innovations. The circulation of knowledge can be readily understood via the example of how injections of education in sustainable development circulate within the economy in five steps:[35]

Step 1: When investments flow into the education helix to promote sustainable development, they create new impulses and suggestions for knowledge creation in the education system. Therefore, a larger output of innovations from science and research can be obtained. Simultaneously, teaching and training improve their effectiveness. The output that arises from human capital for sustainable development is then an input into the economic system helix.

Step 2: Through the input of new knowledge via human capital into the economic system helix, the value of the knowledge economy consequently increases. Through the enhancement of knowledge, important further production facilitates and develops opportunities for a sustainable, future-sensitive green economy, based on knowledge creation. This knowledge creation realizes in the economic system new types of jobs, new green products and new green services, together with new and decisive impulses for greener economic growth. In this subsystem, new values, like corporate social responsibility, are demanded, enabling and supporting a new output of know-how and innovations by the economic system into the natural environment helix.

Step 3: This new sustainability as an output of the economic system is a new input of knowledge in the natural environment helix. This new knowledge ‘communicates’ to nature and results in less exploitation, destruction, contamination, and wastefulness. The natural environment can, thus, regenerate itself and strengthen its natural capital, and humanity can also learn from nature via new knowledge creation. The goal of this helix is to live in balance with nature, to develop regenerative technologies, and to use available, finite resources sustainably. Here, natural science disciplines come into play, forming new green know-how. This know-how is then an output of the natural environment subsystem into the public helix.

Step 4: The output of the natural environment results in an input of new knowledge about nature and a greener lifestyle for the media-based and culture-based public helix. Here, the media-based public receives information capital, which spreads through the media information about a new green consciousness. This capital should provide incentives on how a green lifestyle can be implemented in a simple, affordable, and conscious way, i.e., knowledge creation. This knowledge creation promotes the social capital of the culture-based public, on which a society depends for sustainable development. This know-how output then serves as new input, about the wishes, needs, problems, or satisfaction of citizens, for the political system helix.

Step 5: The input of knowledge into the political system is the know-how from the media-based and culture-based public together with the collective knowledge from the three other subsystems of society. Important discussions on this new knowledge in the political systems are necessary impulses for knowledge creation. The goal of this knowledge creation is political and legal capital, making the quintuple helix model more effective and more sustainable. Consequently, there is an output of suggestions, sustainable investments, and objectives. This leads to the circulation of knowledge back into the education system.

5. Implications for Quality of Democracy

The quintuple helix has implications for the quality of democracy because it embeds civil society and the media (the quadruple helix) within the helical architecture (government, university, industry, civil society and the environment).[36][37][38] Within quintuple helix literature, this is referred to as the ‘democracy of knowledge’.[39] The democracy of knowledge “highlights and underscores parallel processes between political pluralism in advanced democracy, and knowledge and innovation heterogeneity and diversity in advanced economy and society.”[40] It is therefore a form of overlapping of the knowledge economy, the knowledge society and the 'knowledge democracy' and extends the ‘republic of science’ concept[41] put forth by Michael Polanyi.

6. Quintuple Helix and Policy Making

The quintuple helix presents an inter-disciplinary and trans-disciplinary framework of analysis that relates knowledge, innovation and the environment (natural environments) to each other. The quintuple helix has been applied to the 'green new deal';[42] the quality of democracy,[43][44][45][46] including in innovation systems;[47] international cooperation;[48] forest-based bioeconomies;[49] the Russian Arctic zone energy shelf;[50] regional ecosystems;[51] smart specialization and living labs;[52] and innovation diplomacy,[53] a quintuple-helix based extension of science diplomacy.

References

- Carayannis, Elias G.; Campbell, David F.J. (2010). "Triple Helix, Quadruple Helix and Quintuple Helix and How Do Knowledge, Innovation and the Environment Relate To Each Other?: A Proposed Framework for a Trans-disciplinary Analysis of Sustainable Development and Social Ecology" (in en). International Journal of Social Ecology and Sustainable Development 1 (1): 61–62. doi:10.4018/jsesd.2010010105. ISSN 1947-8402. https://semanticscholar.org/paper/89b7a6e5c8e1266b84f8a37d860a24517a90d232.

- 1939-, Gibbons, Michael (1994). The new production of knowledge : the dynamics of science and research in contemporary societies. Nowotny, Helga,, Schwartzman, Simon, 1939-, Scott, Peter, 1946-, Trow, Martin A., 1926-2007. London. ISBN 978-0803977938. OCLC 32093699. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/32093699

- Carayannis, Elias G.; Campbell, David F.J. (2010). "Triple Helix, Quadruple Helix and Quintuple Helix and How Do Knowledge, Innovation and the Environment Relate To Each Other?: A Proposed Framework for a Trans-disciplinary Analysis of Sustainable Development and Social Ecology" (in en). International Journal of Social Ecology and Sustainable Development 1 (1): 48. doi:10.4018/jsesd.2010010105. ISSN 1947-8402. https://semanticscholar.org/paper/89b7a6e5c8e1266b84f8a37d860a24517a90d232.

- 1939-, Gibbons, Michael (1994). The new production of knowledge : the dynamics of science and research in contemporary societies. Nowotny, Helga,, Schwartzman, Simon, 1939-, Scott, Peter, 1946-, Trow, Martin A., 1926-2007. London. ISBN 978-0803977938. OCLC 32093699. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/32093699

- 1939-, Gibbons, Michael (1994). The new production of knowledge : the dynamics of science and research in contemporary societies. Nowotny, Helga,, Schwartzman, Simon, 1939-, Scott, Peter, 1946-, Trow, Martin A., 1926-2007. London. pp. 3=4. ISBN 978-0803977938. OCLC 32093699. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/32093699

- Etzkowitz, Henry; Leydesdorff, Loet (2000). "The dynamics of innovation: from National Systems and "Mode 2" to a Triple Helix of university–industry–government relations" (in en). Research Policy 29 (2): 109–123. doi:10.1016/S0048-7333(99)00055-4. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2FS0048-7333%2899%2900055-4

- Etzkowitz, Henry; Leydesdorff, Loet (1995). "The Triple Helix -- University-Industry-Government Relations: A Laboratory for Knowledge Based Economic Development". EASST Review 14: 14–19.

- Etzkowitz, Henry; Leydesdorff, Loet (2000). "The dynamics of innovation: from National Systems and "Mode 2" to a Triple Helix of university–industry–government relations" (in en). Research Policy 29 (2): 118. doi:10.1016/S0048-7333(99)00055-4. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2FS0048-7333%2899%2900055-4

- Etzkowitz, Henry; Leydesdorff, Loet (2000). "The dynamics of innovation: from National Systems and "Mode 2" to a Triple Helix of university–industry–government relations" (in en). Research Policy 29 (2): 111–112. doi:10.1016/S0048-7333(99)00055-4. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2FS0048-7333%2899%2900055-4

- Carayannis, Elias G.; Campbell, David F.J. (2006). "Meaning and Implications from a Knowledge Systems Perspective". Knowledge creation, diffusion, and use in innovation networks and knowledge clusters. A comparative systems approach across the United States, Europe and Asia. Praeger Publishers. pp. 1–25. ISBN 978-1567204865.

- Carayannis, Elias G.; Campbell, David F.J. (2010). "Triple Helix, Quadruple Helix and Quintuple Helix and How Do Knowledge, Innovation and the Environment Relate To Each Other?: A Proposed Framework for a Trans-disciplinary Analysis of Sustainable Development and Social Ecology" (in en). International Journal of Social Ecology and Sustainable Development 1 (1): 57. doi:10.4018/jsesd.2010010105. ISSN 1947-8402. https://semanticscholar.org/paper/89b7a6e5c8e1266b84f8a37d860a24517a90d232.

- Carayannis, Elias G.; Campbell, David F.J. (2010). "Triple Helix, Quadruple Helix and Quintuple Helix and How Do Knowledge, Innovation and the Environment Relate To Each Other?: A Proposed Framework for a Trans-disciplinary Analysis of Sustainable Development and Social Ecology" (in en). International Journal of Social Ecology and Sustainable Development 1 (1): 51–52. doi:10.4018/jsesd.2010010105. ISSN 1947-8402. https://semanticscholar.org/paper/89b7a6e5c8e1266b84f8a37d860a24517a90d232.

- Cavallini, Simona; Soldi, Rossella; Friedl, Julia; Volpe, Margherita (2016). "Using the Quadruple Helix Approach to Accelerate the Transfer of Research and Innovation Results to Regional Growth". European Union Committee of the Regions. http://cor.europa.eu/en/documentation/studies/Documents/quadruple-helix.pdf.

- Carayannis, E.G.; Campbell, D.F.J. (2009). "'Mode 3' and 'Quadruple Helix': toward a 21st century fractal innovation ecosystem". International Journal of Technology Management 46 (3/4): 201–234. doi:10.1504/IJTM.2009.023374. https://edisciplinas.usp.br/pluginfile.php/3572572/mod_resource/content/1/8-carayannis2009.pdf.

- Rönkä, K; Orava, J (2007) (in Finnish). Kehitysalustoilla neloskierteeseen. Käyttäjälähtöiset living lab- ja testbed-innovaatioympäristöt. Tulevaisuuden kehitysalustat -hankkeen loppuraportti. Helsinki: Movense Oy & The Center for Knowledge and Innovation Research, HSE.

- Arnkil, Robert; Järvensivu, Anu; Koski, Pasi; Piirainen, Tatu (2010). Exploring Quadruple Helix: Outlining user-oriented innovation models. Tampere: University of Tampere. ISBN 978-951-44-8208-3. http://tampub.uta.fi/handle/10024/65758.

- MacGregor, Steven P. (2010). CLIQboost : baseline research for CLIQ INTERREGIVC (Creating Local Innovations for SMEs through a Quadruple Helix) : presented by the University of Girona to the city of Jyväskylä. Girona: Documenta Universitaria. ISBN 9788492707348. OCLC 804706118. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/804706118

- Plasser, Fritz (2004). Politische Kommunikation in Österreich : ein praxisnahes Handbuch. Wien: WUV. pp. 22–23. ISBN 3851148584. OCLC 57566424. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/57566424

- Carayannis, Elias G.; Campbell, David F.J. (2009). "'Mode 3' and 'Quadruple Helix': toward a 21st century fractal innovation ecosystem" (in en). International Journal of Technology Management 46 (3/4): 218. doi:10.1504/IJTM.2009.023374. ISSN 0267-5730. https://semanticscholar.org/paper/6716912960e98af379c65344188e84198c65b488.

- Carayannis, Elias G.; Campbell, David F.J. (2009). "'Mode 3' and 'Quadruple Helix': toward a 21st century fractal innovation ecosystem" (in en). International Journal of Technology Management 46 (3/4): 219. doi:10.1504/IJTM.2009.023374. ISSN 0267-5730. https://semanticscholar.org/paper/6716912960e98af379c65344188e84198c65b488.

- Carayannis, Elias G.; Campbell, David F.J. (2009). "'Mode 3' and 'Quadruple Helix': toward a 21st century fractal innovation ecosystem" (in en). International Journal of Technology Management 46 (3/4): 219. doi:10.1504/IJTM.2009.023374. ISSN 0267-5730. https://semanticscholar.org/paper/6716912960e98af379c65344188e84198c65b488.

- Carayannis, Elias G.; Campbell, David F.J. (2009). "'Mode 3' and 'Quadruple Helix': toward a 21st century fractal innovation ecosystem" (in en). International Journal of Technology Management 46 (3/4): 219. doi:10.1504/IJTM.2009.023374. ISSN 0267-5730. https://semanticscholar.org/paper/6716912960e98af379c65344188e84198c65b488.

- Kuhlmann, Stefan (2001). "Future governance of innovation policy in Europe — three scenarios" (in en). Research Policy 30 (6): 954. doi:10.1016/S0048-7333(00)00167-0. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2FS0048-7333%2800%2900167-0

- Höglund, Linda; Linton, Gabriel (2018). "Smart specialization in regional innovation systems: a quadruple helix perspective: Smart specialization in regional innovation systems" (in en). R&D Management 48 (1): 60–72. doi:10.1111/radm.12306. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2Fradm.12306

- Höglund, Linda; Linton, Gabriel (2018). "Smart specialization in regional innovation systems: a quadruple helix perspective: Smart specialization in regional innovation systems" (in en). R&D Management 48 (1): 60–72. doi:10.1111/radm.12306. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2Fradm.12306

- Lew, Yong Kyu; Khan, Zaheer; Cozzio, Sara (2018). "Gravitating toward the quadruple helix: international connections for the enhancement of a regional innovation system in Northeast Italy" (in en). R&D Management 48 (1): 44–59. doi:10.1111/radm.12227. http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/101137/3/Quadruple%20Helix%20R%2526D%20managementforthcoming2016.pdf.

- Höglund, Linda; Linton, Gabriel (2018). "Smart specialization in regional innovation systems: a quadruple helix perspective: Smart specialization in regional innovation systems" (in en). R&D Management 48 (1): 60–72. doi:10.1111/radm.12306. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2Fradm.12306

- Vallance, Paul (2017). "The co-evolution of regional innovation domains and institutional arrangements: Smart specialisation through quadruple helix relations?". in Philip, McCann. The Empirical and Institutional Dimensions of Smart Specialisation. Abingdon: Routledge. pp. 127–144. ISBN 978-113869575-7.

- Cresson, Edith (17 November 1997). Towards a Knowledge-based Europe. Lecture by Mrs Edith Cresson at the London School of Economics and Political Science.

- "GUIDELINES FOR LIVING LABS IN CLIMATE SERVICES – EU MACS" (in en). http://eu-macs.eu/outputs/livinglabs/.

- hubavem (2013-12-04). "Open Innovation 2.0" (in en). https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/open-innovation-20.

- Carayannis, Elias G. (2017-03-01). The quadruple innovation helix nexus : a smart growth model, quantitative empirical validation and operationalization for OECD countries. Monteiro, Sara Paulina de Oliveira,, Carayannis, Elias G.. New York. ISBN 9781137555779. OCLC 974489134. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/974489134

- Barth, Thorsten D. (2011). "The Idea of a Green New Deal in a Quintuple Helix Model of Knowledge, Know-How and Innovation" (in en). International Journal of Social Ecology and Sustainable Development 2 (1): 6. doi:10.4018/jsesd.2011010101. ISSN 1947-8402. https://semanticscholar.org/paper/acb5df373a8baa3328fb072f0efa4be7f383d221.

- Carayannis, Elias G.; Campbell, David F.J. (2010). "Triple Helix, Quadruple Helix and Quintuple Helix and How Do Knowledge, Innovation and the Environment Relate To Each Other?: A Proposed Framework for a Trans-disciplinary Analysis of Sustainable Development and Social Ecology" (in en). International Journal of Social Ecology and Sustainable Development 1 (1): 46–48, 62. doi:10.4018/jsesd.2010010105. ISSN 1947-8402. https://semanticscholar.org/paper/89b7a6e5c8e1266b84f8a37d860a24517a90d232.

- Carayannis, Elias G.; Barth, Thorsten D.; Campbell, David F.J. (2012). "The Quintuple Helix innovation model: global warming as a challenge and driver for innovation". Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship 1 (2): 2. doi:10.1186/2192-5372-1-2. https://dx.doi.org/10.1186%2F2192-5372-1-2

- Carayannis, Elias G; Campbell, David FJ (2014). "Developed democracies versus emerging autocracies: arts, democracy, and innovation in Quadruple Helix innovation systems" (in en). Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship 3 (1). doi:10.1186/s13731-014-0012-2. ISSN 2192-5372. https://dx.doi.org/10.1186%2Fs13731-014-0012-2

- Schlattl, Gerhard (2013). "The Quality of Democracy-Concept vs. the Quintuple Helix: On the Virtues of Minimalist vs. Maximalist Approaches in Assessing the Quality of Democracy and the Quality of Society" (in en). International Journal of Social Ecology and Sustainable Development 4 (1): 66–85. doi:10.4018/jsesd.2013010104. ISSN 1947-8402. https://semanticscholar.org/paper/5a90ad21ddd2ff13cf252c4c65a99a8cdc8e8007.

- Carayannis, Elias G.; Campbell, David F. J. (2017). "Les systèmes d'innovation de la quadruple et de la quintuple hélice" (in fr). Innovations 54 (3): 173. doi:10.3917/inno.pr1.0023. ISSN 1267-4982. https://dx.doi.org/10.3917%2Finno.pr1.0023

- Carayannis, Elias G.; Kaloudis, Aris (2010). "A Time for Action and a Time to Lead: Democratic Capitalism and a New "New Deal" for the US and the World in the Twenty-first Century" (in en). Journal of the Knowledge Economy 1 (1): 9. doi:10.1007/s13132-009-0002-y. ISSN 1868-7865. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2Fs13132-009-0002-y

- G., Carayannis, Elias (2012). Mode 3 knowledge production in quadruple helix innovation systems : 21st-century democracy, innovation, and entrepreneurship for development. Campbell, David F. J., 1963-. New York, NY: Springer. pp. 55. ISBN 9781461420620. OCLC 768111055. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/768111055

- Polanyi, Michael (1962). "The Republic of science: Its political and economic theory" (in en). Minerva 1 (1): 54–73. doi:10.1007/BF01101453. ISSN 0026-4695. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2FBF01101453

- Barth, Thorsten D. (2011). "The Idea of a Green New Deal in a Quintuple Helix Model of Knowledge, Know-How and Innovation" (in en). International Journal of Social Ecology and Sustainable Development 2 (1): 1–14. doi:10.4018/jsesd.2011010101. ISSN 1947-8402. https://semanticscholar.org/paper/acb5df373a8baa3328fb072f0efa4be7f383d221.

- Carayannis, Elias G.; Kaloudis, Aris (2010). "A Time for Action and a Time to Lead: Democratic Capitalism and a New "New Deal" for the US and the World in the Twenty-first Century" (in en). Journal of the Knowledge Economy 1 (1): 4–17. doi:10.1007/s13132-009-0002-y. ISSN 1868-7865. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2Fs13132-009-0002-y

- Carayannis, Elias G; Campbell, David FJ (2014). "Developed democracies versus emerging autocracies: arts, democracy, and innovation in Quadruple Helix innovation systems" (in en). Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship 3 (1). doi:10.1186/s13731-014-0012-2. ISSN 2192-5372. https://dx.doi.org/10.1186%2Fs13731-014-0012-2

- Schlattl, Gerhard (2013). "The Quality of Democracy-Concept vs. the Quintuple Helix: On the Virtues of Minimalist vs. Maximalist Approaches in Assessing the Quality of Democracy and the Quality of Society" (in en). International Journal of Social Ecology and Sustainable Development 4 (1): 66–85. doi:10.4018/jsesd.2013010104. ISSN 1947-8402. https://semanticscholar.org/paper/5a90ad21ddd2ff13cf252c4c65a99a8cdc8e8007.

- Carayannis, Elias G.; Campbell, David F. J. (2017). "Les systèmes d'innovation de la quadruple et de la quintuple hélice" (in fr). Innovations 54 (3): 173. doi:10.3917/inno.pr1.0023. ISSN 1267-4982. https://dx.doi.org/10.3917%2Finno.pr1.0023

- Campbell, David F. J.; Carayannis, Elias G.; Rehman, Scheherazade S. (2015). "Quadruple Helix Structures of Quality of Democracy in Innovation Systems: the USA, OECD Countries, and EU Member Countries in Global Comparison" (in en). Journal of the Knowledge Economy 6 (3): 467–493. doi:10.1007/s13132-015-0246-7. ISSN 1868-7865. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2Fs13132-015-0246-7

- Casaramona, Andreana; Sapia, Antonia; Soraci, Alberto (2015). "How TOI and the Quadruple and Quintuple Helix Innovation System Can Support the Development of a New Model of International Cooperation" (in en). Journal of the Knowledge Economy 6 (3): 505–521. doi:10.1007/s13132-015-0253-8. ISSN 1868-7865. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2Fs13132-015-0253-8

- Grundel, Ida; Dahlström, Margareta (2016). "A Quadruple and Quintuple Helix Approach to Regional Innovation Systems in the Transformation to a Forestry-Based Bioeconomy" (in en). Journal of the Knowledge Economy 7 (4): 963–983. doi:10.1007/s13132-016-0411-7. ISSN 1868-7865. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2Fs13132-016-0411-7

- Carayannis, Elias G.; Cherepovitsyn, Alexey E.; Ilinova, Alina A. (2017). "Sustainable Development of the Russian Arctic zone energy shelf: the Role of the Quintuple Innovation Helix Model" (in en). Journal of the Knowledge Economy 8 (2): 456–470. doi:10.1007/s13132-017-0478-9. ISSN 1868-7865. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2Fs13132-017-0478-9

- Carayannis, Elias G.; Grigoroudis, Evangelos; Campbell, David F. J.; Meissner, Dirk; Stamati, Dimitra (2018). "The ecosystem as helix: an exploratory theory-building study of regional co-opetitive entrepreneurial ecosystems as Quadruple/Quintuple Helix Innovation Models: The ecosystem as helix" (in en). R&D Management 48 (1): 148–162. doi:10.1111/radm.12300. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2Fradm.12300

- Provenzano, Vincenzo; Arnone, Massimo; Seminara, Maria Rosaria (2018), Bisello, Adriano; Vettorato, Daniele; Laconte, Pierre et al., eds., "The Links Between Smart Specialisation Strategy, the Quintuple Helix Model and Living Labs", Smart and Sustainable Planning for Cities and Regions (Springer International Publishing): pp. 563–571, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-75774-2_38, ISBN 9783319757735 https://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2F978-3-319-75774-2_38

- Carayannis, Elias G.; Campbell, David F. J. (2011). "Open Innovation Diplomacy and a 21st Century Fractal Research, Education and Innovation (FREIE) Ecosystem: Building on the Quadruple and Quintuple Helix Innovation Concepts and the "Mode 3" Knowledge Production System" (in en). Journal of the Knowledge Economy 2 (3): 327–372. doi:10.1007/s13132-011-0058-3. ISSN 1868-7865. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2Fs13132-011-0058-3