| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Catherine Yang | -- | 3200 | 2022-11-22 01:33:56 |

Video Upload Options

1. Introduction

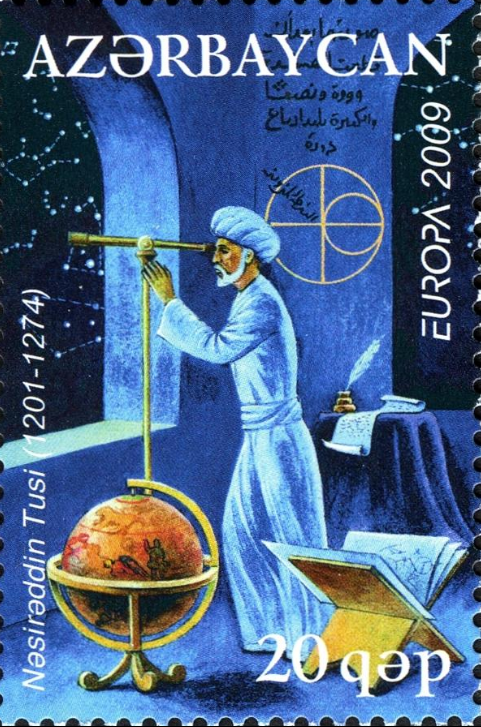

Muhammad ibn Muhammad ibn al-Hasan al-Tūsī (Persian: محمد ابن محمد ابن حسن طوسی 18 February 1201 – 26 June 1274), better known as Nasir al-Din al-Tusi (Persian: نصیر الدین طوسی; or simply Tusi /ˈtuːsi/[1] in the West), was a Persian polymath, architect, philosopher, physician, scientist, and theologian.[2] Nasir al-Din al-Tusi was a well published author, writing on subjects of math, engineering, prose, and mysticism. Additionally, al-Tusi made several scientific advancements. In astronomy, al-Tusi created very accurate tables of planetary motion, an updated planetary model, and critiques of Ptolemaic astronomy. He also made strides in logic, mathematics but especially trigonometry, biology, and chemistry. Nasir al-Din al-Tusi left behind a great legacy as well. Some consider Tusi one of the greatest scientists of medieval Islam,[3] since he is often considered the creator of trigonometry as a mathematical discipline in its own right.[4][5][6] The Muslim scholar Ibn Khaldun (1332–1406) considered Tusi to be the greatest of the later Persian scholars.[7] There is also reason to believe that he may have influenced Copernican heliocentrism.[8][9][10][11][12][13]

2. Biography

Nasir al-Din al-Tusi was born in the city of Tus in medieval Khorasan (northeastern Iran) in the year 1201 and began his studies at an early age. In Hamadan and Tus he studied the Quran, hadith, Ja'fari jurisprudence, logic, philosophy, mathematics, medicine, and astronomy.[14]

He was born into a Shī‘ah family and lost his father at a young age. Fulfilling the wish of his father, the young Muhammad took learning and scholarship very seriously and traveled far and wide to attend the lectures of renowned scholars and acquired knowledge, an exercise highly encouraged in his Islamic faith. At a young age, he moved to Nishapur to study philosophy under Farid al-Din Damad and mathematics under Muhammad Hasib.[15] He met also Attar of Nishapur, the legendary Sufi master who was later killed by the Mongols, and he attended the lectures of Qutb al-Din al-Misri.

Nasir-al-Din Tusi writes in his work, Desideratum of the Faithful (Maṭlūb al-muʾminīn),“To become people of spiritual reality, it is incumbent to fulfill the symbolic elucidation (ta'wīl) of the seven pillars of the religious law (sharīʿat)”. He also explains that fulfilling the religious law is much easier than fulfilling its spiritual interpretation.[16]

He explains in his book Aghaz u anjam that the sacred accounts of history that we perceive within the bounds of space and time symbolize events that have no such restrictions. They are only expressed in this way so that humans are able to comprehend them.[17]

In Mosul, al-Tusi studied mathematics and astronomy with Kamal al-Din Yunus (d. AH 639 / AD 1242), a pupil of Sharaf al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī.[18] Later on he corresponded with Sadr al-Din al-Qunawi, the son-in-law of Ibn Arabi, and it seems that mysticism, as propagated by Sufi masters of his time, was not appealing to him. Once the occasion was suitable, he composed his own manual of philosophical Sufism in the form of a small booklet entitled Awsaf al-Ashraf, or "The Attributes of the Illustrious".

As the armies of Genghis Khan swept his homeland, he was employed by the Nizari Ismaili state and, while moving from stronghold to stronghold, made his most important contributions in science,[19] first in those of the Quhistan region under Muhtasham Nasir al-Din Abd al-Rahim ibn Abi Mansur (where he wrote the Nasirean Ethics). He was later sent to the major castles of Alamut and Maymun-Diz to continue his career under Nizari Imam Ala al-Din Muhammad.[20][21] He was captured after the fall of Maymun-Diz to the Mongol forces under Hulagu Khan.[22]

Nasir al-Din Tusi’s autobiography, The Voyage (Sayr wa-Suluk) explains that a literary devastation such as the devastation of the Alamūt libraries in 1256 would not waver the spirit of the Nizari Ismaili community because they give more importance to the “living book” (the Imam of the Time) rather than the “written word”. Their hearts are attached to the Commander of the Believers (amir al-mu'minin), not just the “command” itself. There is always a present living Imam in world, and following him, a believer will never go astray.[23]

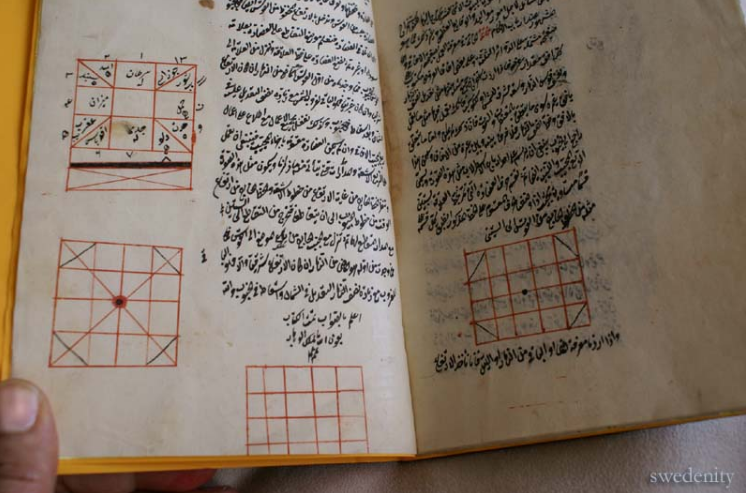

3. Works

Tusi has about 150 works, of which 25 are in Persian and the remaining are in Arabic,[24] and there is one treatise in Persian, Arabic and Turkish.[25]

- Sayr wa-Suluk (The Voyage) - Autobiography[23]

- Kitāb al-Shakl al-qattāʴ Book on the complete quadrilateral. A five-volume summary of trigonometry.

- Al-Tadhkirah fi'ilm al-hay'ah – A memoir on the science of astronomy. Many commentaries were written about this work called Sharh al-Tadhkirah (A Commentary on al-Tadhkirah) - Commentaries were written by Abd al-Ali ibn Muhammad ibn al-Husayn al-Birjandi and by Nazzam Nishapuri.

- Akhlaq-i Nasiri – A work on ethics.

- al-Risalah al-Asturlabiyah – A Treatise on the astrolabe.

- Zij-i Ilkhani (Ilkhanic Tables) – A major astronomical treatise, completed in 1272.

- Sharh al-Isharat (Commentary on Avicenna's Isharat)

- Awsaf al-Ashraf a short mystical-ethical work in Persian.[26]

- Tajrīd al-Iʿtiqād (Summation of Belief) – A commentary on Shia doctrines.

- Talkhis al-Muhassal (summary of summaries).

- Maṭlūb al-muʾminīn (Desideratum of the Faithful)[16]

- Aghaz u anjam - Esoteric interpretation of the Quran[17]

An example from one of his poems:

Anyone who knows, and knows that he knows,

makes the steed of intelligence leap over the vault of heaven.

Anyone who does not know but knows that he does not know,

can bring his lame little donkey to the destination nonetheless.

Anyone who does not know, and does not know that he does not know,

is stuck forever in double ignorance.

4. Achievements

During his stay in Nishapur, Tusi established a reputation as an exceptional scholar. Tusi’s prose writing, which numbers over 150 works, represent one of the largest collections by a single Islamic author. Writing in both Arabic and Persian, Nasir al-Din Tusi dealt with both religious ("Islamic") topics and non-religious or secular subjects ("the ancient sciences").[24] His works include the definitive Arabic versions of the works of Euclid, Archimedes, Ptolemy, Autolycus, and Theodosius of Bithynia.[24]

4.1. Astronomy

Tusi convinced Hulegu Khan to construct an observatory for establishing accurate astronomical tables for better astrological predictions. Beginning in 1259, the Rasad Khaneh observatory was constructed in Azarbaijan, south of the river Aras, and to the west of Maragheh, the capital of the Ilkhanate Empire.[27]

Based on the observations in this for the time being most advanced observatory, Tusi made very accurate tables of planetary movements as depicted in his book Zij-i ilkhani (Ilkhanic Tables). This book contains astronomical tables for calculating the positions of the planets and the names of the stars. His model for the planetary system is believed to be the most advanced of his time, and was used extensively until the development of the heliocentric model in the time of Nicolaus Copernicus. Between Ptolemy and Copernicus, he is considered by many to be one of the most eminent astronomers of his time. His famous student Shams al-Din al-Bukhari[28] was the teacher of Byzantine scholar Gregory Chioniades,[29] who had in turn trained astronomer Manuel Bryennios[30] about 1300 in Constantinople.

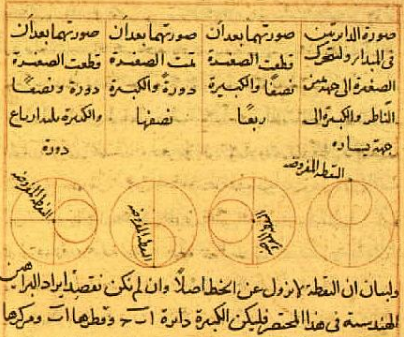

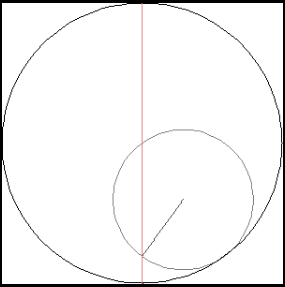

For his planetary models, he invented a geometrical technique called a Tusi-couple, which generates linear motion from the sum of two circular motions. He used this technique to replace Ptolemy's problematic equant[31] for many planets, but was unable to find a solution to Mercury, which was solved later by Ibn al-Shatir as well as Ali Qushji.[32] The Tusi couple was later employed in Ibn al-Shatir's geocentric model and Nicolaus Copernicus' heliocentric Copernican model.[33] He also calculated the value for the annual precession of the equinoxes and contributed to the construction and usage of some astronomical instruments including the astrolabe.

Ṭūsī criticized Ptolemy's use of observational evidence to show that the Earth was at rest, noting that such proofs were not decisive. Although it doesn't mean that he was a supporter of mobility of the earth, as he and his 16th-century commentator al-Bīrjandī, maintained that the earth's immobility could be demonstrated, only by physical principles found in natural philosophy.[34] Tusi's criticisms of Ptolemy were similar to the arguments later used by Copernicus in 1543 to defend the Earth's rotation.[35]

About the real essence of the Milky Way, Ṭūsī in his Tadhkira writes: "The Milky Way, i.e. the galaxy, is made up of a very large number of small, tightly-clustered stars, which, on account of their concentration and smallness, seem to be cloudy patches. because of this, it was likened to milk in color." [36] Three centuries later the proof of the Milky Way consisting of many stars came in 1610 when Galileo Galilei used a telescope to study the Milky Way and discovered that it is really composed of a huge number of faint stars.[37]

4.2. Logic

Nasir al-Din Tusi was a supporter of Avicennian logic, and wrote the following commentary on Avicenna's theory of absolute propositions:

"What spurred him to this was that in the assertoric syllogistic Aristotle and others sometimes used contradictories of absolute propositions on the assumption that they are absolute; and that was why so many decided that absolutes did contradict absolutes. When Avicenna had shown this to be wrong, he wanted to develop a method of construing those examples from Aristotle."[38]

4.3. Mathematics

Al-Tusi was the first to write a work on trigonometry independently of astronomy.[39] Al-Tusi, in his Treatise on the Quadrilateral, gave an extensive exposition of spherical trigonometry, distinct from astronomy.[40] It was in the works of Al-Tusi that trigonometry achieved the status of an independent branch of pure mathematics distinct from astronomy, to which it had been linked for so long.[41][42]

He was the first to list the six distinct cases of a right triangle in spherical trigonometry.[43]

This followed earlier work by Greek mathematicians such as Menelaus of Alexandria, who wrote a book on spherical trigonometry called Sphaerica, and the earlier Muslim mathematicians Abū al-Wafā' al-Būzjānī and Al-Jayyani.

In his On the Sector Figure, appears the famous Sine Law for plane triangles.[44]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{a}{\sin A} = \frac{b}{\sin B} = \frac{c}{\sin C} }[/math]

He also stated the sine law for spherical triangles,[45][46] discovered the law of tangents for spherical triangles, and provided proofs for these laws.[44]

4.4. Color Theory

While Aristotle (d. 322 BCE) had suggested that all colors can be aligned on a single line from black to white, Ibn-Sina (d. 1037) described that there were three paths from black to white, one path via grey, a second path via red and the third path via green. Al-Tusi (ca. 1258) stated that there are no less than five of such paths, via lemon (yellow), blood (red), pistachio (green), indigo (blue) and grey. This text, which was copied in the Middle East numerous times until at least the nineteenth century as part of the textbook Revision of the Optics (Tanqih al-Manazir) by Kamal al-Din al-Farisi (d. 1320), made color space effectively two-dimensional.[47] Robert Grosseteste (d. 1253) proposed an effectively three-dimensional model of color space.[48]

4.5. Biology

In his Akhlaq-i Nasiri, Tusi wrote about several biological topics. He defended a version of Aristotle's scala naturae, in which he placed man above animals, plants, minerals, and the elements. He described "grasses which grow without sowing or cultivation, by the mere mingling of elements,"[49] as closest to minerals. Among plants, he considered the date-palm as the most highly developed, since "it only lacks one thing further to reach (the stage of) an animal: to tear itself loose from the soil and to move away in the quest for nourishment."[49]

The lowest animals "are adjacent to the region of plants: such are those animals which propagate like grass, being incapable of mating [...], e.g. earthworms, and certain insects".[50] The animals "which reach the stage of perfection [...] are distinguished by fully developed weapons", such as antlers, horns, teeth, and claws. Tusi described these organs as adaptations to each species's lifestyle, in a way anticipating natural theology. He continued:

"The noblest of the species is that one whose sagacity and perception is such that it accepts discipline and instruction: thus there accrues to it the perfection not originally created in it. Such are the schooled horse and the trained falcon. The greater this faculty grows in it, the more surpassing its rank, until a point is reached where the (mere) observation of action suffices as instruction: thus, when they see a thing, they perform the like of it by mimicry, without training [...]. This is the utmost of the animal degrees, and the first of the degrees of Man in contiguous therewith."[51]

Thus, in this paragraph, Tusi described different types of learning, recognising observational learning as the most advanced form, and correctly attributing it to certain animals.

Tusi seems to have perceived man as belonging to the animals, since he stated that "the Animal Soul [comprising the faculties of perception and movement ...] is restricted to individuals of the animal species", and that, by possessing a "Human Soul, [...] mankind is distinguished and particularized among other animals."[52]

Some scholars have interpreted Tusi's biological writings as suggesting that he adhered to some kind of evolutionary theory.[53][54] However, Tusi did not state explicitly that he believed species to change over time.

4.6. Chemistry

Tusi contributed to the field of chemistry, stating an early law of conservation of mass.[55]

4.7. Philosophy

Tusi contributed many writings to the topic of philosophy. Amongst his philosophical work are his disagreements with fellow philosopher Avicenna. His most famous philosophical work is Akhlaq-i nasiri or Nasirean Ethics in English.[56] Within this work he discusses and compares Islamic teachings to the ethics of Aristotle and Plato. Tusi's book became a popular ethical work in the Muslim world, specifically in India and Persia.[56] Tusi's work also left an impact on Shi'ite Islamic theology. His book Targid also called Catharsis is significant in Shi'ite theology.[57] He also contributed five works to the subject of logic; which were highly regarded by his contemporaries and achieved notoriety in the Muslim world.[57]

5. Influence and Legacy

A 60-km diameter lunar crater located on the southern hemisphere of the moon is named after him as "Nasireddin". A minor planet 10269 Tusi discovered by Soviet astronomer Nikolai Stepanovich Chernykh in 1979 is named after him.[58][59] The K. N. Toosi University of Technology in Iran and Observatory of Shamakhy in the Republic of Azerbaijan are also named after him. In February 2013, Google celebrated his 812th birthday with a doodle, which was accessible in its websites with Arabic language calling him al-farsi (the Persian).[60][61] His birthday is also celebrated as Engineer's Day in Iran.[62]

5.1. Possible Influence on Nicolaus Copernicus

Some scholars believe that Nicolaus Copernicus may have been influenced by Middle Eastern astronomers due to uncanny similarities between his work and the uncited work of these Islamic scholars, including Nasir al-Din al-Tusi, Ibn al-Shatir, Muayyad al-Din al-Urdi, and Qutb al-Din al-Shirazi.[8][9][10][11][12][13] al-Tusi specifically, the plagiarism in question comes from similarities in the Tusi couple and Copernicus' geometric method of removing the Equant from mathematical astronomy.[10][12] Not only do both of the methods match geometrically, however, more importantly they both use the same exact lettering system for each vertex; a detail that seems too preternatural to be happenstance.[10][12] Moreover, the fact that several other details of his model also mirror other Islamic scholars bolsters the notion that Copernicus' work may not have been only his own.[12]

There is no evidence that any of the direct work of Nasir al-Din al-Tusi ever made it to Copernicus, however there is evidence that the mathematics and theories did make the journey to Europe.[8][9] There were Jewish scientists and pilgrims who would make the journey from the Middle East to Europe, bringing with them Middle Eastern scientific ideas to share with their Christian counterparts.[9] While acknowledging that this is not direct evidence that Copernicus has access to al-Tusi's work, it does show that it was possible.[9] There was just such a Jewish scholar by the name of Abner of Burgos who wrote a book containing an incomplete version of the Tusi couple that he had learned second hand, which could have been found by Copernicus.[8] It is important to note that his version had no proofs of the geometry either, so if Copernicus had obtained this book he would have had to complete both the proof and mechanism.[8] Additionally, some scholars believe that, if not Jewish thinkers, it could have been transmission from the Islamic school in Maragheh, home to Nasir al-Din al-Tusi's observatory to Muslim Spain.[8][9] From Spain, al-Tusi and other Islamic cosmological theories could spread through Europe.[8][9] Spread of Islamic astronomy from Maragheh Observatory into Europe could have also been possible in the form of Greek translations from Gregory Choniades.[9] There is evidence as to the means of Copernicus acquiring the Tusi couple and suspicious similarities, not only in math but in visual details as well.[8][9][10][11][12][13]

Despite this circumstantial evidence, there is still no direct proof that Copernicus did plagiarize the work of Nasir al-Din al-Tusi, and if he did that he did so intentionally.[10][63][64][65] The Tusi couple is not a unique principle, and as the equant was a problematic necessity to preserve circular motion it is possible that more than one astronomer wished to improve on it; to that end, some scholars argue it would not be difficult for an astronomer to use Euclid's own work to derive the Tusi couple on their own, and that Copernicus most likely did this instead of stealing.[63][64] Before Copernicus ever published the work on his geometrical mechanism, he had written at length his dissatisfaction over Ptolemaic astronomy and the use of the equant, so some scholars then purport that it was not unfounded for Copernicus to have rederived the Tusi couple without having seen it as he had clear motive to do so.[64] Also, some scholars that argue Copernicus did commit plagiarism say that by never claiming it as his own, he inherently condemns himself.[65] However, others critique that mathematicians do not normally claim work like other scientists, so declaring a theorem for oneself is an exception and not the norm.[65] Therefore, there is motive and some explanation as to why and how Copernicus did not plagiarize, despite the evidence against him.[63][64][65]

References

- "Tusi". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary. http://www.dictionary.com/browse/tusi

- Bennison, Amira K. (2009). The great caliphs : the golden age of the 'Abbasid Empire. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 204. ISBN 978-0-300-15227-2. "Hulegu killed the last ‘Abbasid caliph but also patronized the foundation of a new observatory at Maragha in Azerbayjan at the instigation of the Persian Shi‘i polymath Nasir al-Din Tusi." Goldschmidt, Arthur; Boum, Aomar (2015). A Concise History of the Middle East. Avalon Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8133-4963-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=hSOdBAAAQBAJ. "Hulegu, contrite at the damage he had wrought, patronized the great Persian scholar, Nasiruddin Tusi (died 1274), who saved the lives of many other scientists and artists, accumulated a library of 400000 volumes, and built an astronomical ..." Bar Hebraeus; Joosse, Nanne Pieter George (2004). A Syriac Encyclopaedia of Aristotelian Philosophy: Barhebraeus (13th C.), Butyrum Sapientiae, Books of Ethics, Economy, and Politics : a Critical Edition, with Introduction, Translation, Commentary, and Glossaries. Brill. p. 11. ISBN 978-90-04-14133-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=eYV3AAAAMAAJ. "the Persian scholar Naṣīr al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī" Seyyed Hossein Nasr (2006). Islamic Philosophy from Its Origin to the Present: Philosophy in the Land of Prophecy. State University of New York Press. p. 167. ISBN 978-0-7914-6800-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=0k5iy4RvAwcC. "In fact it was common among Persian Islamic philosophers to write few quatrains on the side often in the spirit of some of the poems of Khayyam singing about the impermanence of the world and its transience and similar themes. One needs to only recall the names of Ibn Sina, Suhrawardi, Nasir al-Din Tusi and Mulla Sadra, who wrote poems along with extensive prose works." Rodney Collomb, "The rise and fall of the Arab Empire and the founding of Western pre-eminence", Published by Spellmount, 2006. pg 127: "Khawaja Nasr ed-Din Tusi, the Persian, Khorasani, former chief scholar and scientist of" Seyyed Hossein Nasr, Islamic Philosophy from Its Origin to the Present: Philosophy in the Land of Prophecy, SUNY Press, 2006, ISBN:0-7914-6799-6. page 199 Seyyed H. Badakhchani. Contemplation and Action: The Spiritual Autobiography of a Muslim Scholar: Nasir al-Din Tusi (In Association With the Institute of Ismaili Studies. I. B. Tauris (December 3, 1999). ISBN:1-86064-523-2. page.1: ""Nasir al-Din Abu Ja`far Muhammad b. Muhammad b. Hasan Tusi:, the renowned Persian astronomer, philosopher and theologian" Glick, Thomas F.; Livesey, Steven John; Wallis, Faith (2005). Medieval Science, Technology, and Medicine: An Encyclopedia. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-96930-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=SaJlbWK_-FcC. "drawn by the Persian cosmographer al-Tusi." Laet, Sigfried J. de (1994). History of Humanity: From the seventh to the sixteenth century. UNESCO. p. 908. ISBN 978-92-3-102813-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=PvlthkbFU1UC. "the Persian astronomer and philosopher Nasir al-Din Tusi." Mirchandani, Vinnie (2010). The New Polymath: Profiles in Compound-Technology Innovations. John Wiley & Sons. p. 300. ISBN 978-0-470-76845-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=v7bP_KlooLwC&pg=PA300. "Nasir. al-Din. al-Tusi: Stay. Humble. Nasir al-Din al-Tusi, the Persian polymath, talked about humility: “Anyone who does not know and does not know that he does not know is stuck forever in double ..." Ṭūsī, Naṣīr al-Dīn Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad; Badakchani, S. J. (2005), Paradise of Submission: A Medieval Treatise on Ismaili Thought, Ismaili Texts and Translations, 5, London: I.B. Tauris in association with Institute of Ismaili Studies, pp. 2–3, ISBN 1-86064-436-8

- Brummelen, Glen Van (2009) (in en). The Mathematics of the Heavens and the Earth: The Early History of Trigonometry. Princeton University Press. p. 187. ISBN 978-0-691-12973-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=bHD8IBaYN-oC&q=al-kashi+law+of+cosines&pg=PA182.

- "Al-Tusi_Nasir biography". http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Al-Tusi_Nasir.html. "One of al-Tusi's most important mathematical contributions was the creation of trigonometry as a mathematical discipline in its own right rather than as just a tool for astronomical applications. In Treatise on the quadrilateral al-Tusi gave the first extant exposition of the whole system of plane and spherical trigonometry. This work is really the first in history on trigonometry as an independent branch of pure mathematics and the first in which all six cases for a right-angled spherical triangle are set forth."

- "the cambridge history of science". https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/the-cambridge-history-of-science/islamic-mathematics/4BF4D143150C0013552902EE270AF9C2.

- electricpulp.com. "ṬUSI, NAṢIR-AL-DIN i. Biography – Encyclopaedia Iranica" (in en). http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/tusi-nasir-al-din-bio. "His major contribution in mathematics (Nasr, 1996, pp. 208-14) is said to be in trigonometry, which for the first time was compiled by him as a new discipline in its own right. Spherical trigonometry also owes its development to his efforts, and this includes the concept of the six fundamental formulas for the solution of spherical right-angled triangles."

- James Winston Morris, "An Arab Machiavelli? Rhetoric, Philosophy and Politics in Ibn Khaldun’s Critique of Sufism", Harvard Middle Eastern and Islamic Review 8 (2009), pp 242–291. [1] excerpt from page 286 (footnote 39): "Ibn Khaldun’s own personal opinion is no doubt summarized in his pointed remark (Q 3: 274) that Tusi was better than any other later Iranian scholar". Original Arabic: Muqaddimat Ibn Khaldūn : dirāsah usūlīyah tārīkhīyah / li-Aḥmad Ṣubḥī Manṣūr-al-Qāhirah : Markaz Ibn Khaldūn : Dār al-Amīn, 1998. ISBN:977-19-6070-9. Excerpt from Ibn Khaldun is found in the section: الفصل الثالث و الأربعون: في أن حملة العلم في الإسلام أكثرهم العجم (On how the majority who carried knowledge forward in Islam were Persians) In this section, see the sentence where he mentions Tusi as more knowledgeable than other later Persian ('Ajam) scholars: . و أما غيره من العجم فلم نر لهم من بعد الإمام ابن الخطيب و نصير الدين الطوسي كلاما يعول على نهايته في الإصابة. فاعتير ذلك و تأمله تر عجبا في أحوال الخليقة. و الله يخلق ما بشاء لا شريك له الملك و له الحمد و هو على كل شيء قدير و حسبنا الله و نعم الوكيل و الحمد لله.

- Nosonovsky, Michael (2018-08-14). "Abner of Burgos: The Missing Link between Nasir al-Din al-Tusi and Nicolaus Copernicus?" (in en). Zutot 15 (1): 25–30. doi:10.1163/18750214-12151070. ISSN 1571-7283. https://brill.com/view/journals/zuto/15/1/article-p25_3.xml.

- Morrison, Robert (March 2014). "A Scholarly Intermediary between the Ottoman Empire and Renaissance Europe". Isis 105 (1): 32–57. doi:10.1086/675550. ISSN 0021-1753. PMID 24855871. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/pdfplus/10.1086/675550.

- Pedersen, Olaf (1993-03-11) (in en). Early Physics and Astronomy: A Historical Introduction. CUP Archive. pp. 273–274. ISBN 978-0-521-40899-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=z7M8AAAAIAAJ.

- Rabin, Sheila (2004-11-30). "Nicolaus Copernicus". https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/copernicus/.

- Hartner, Willy (1973). "Copernicus, the Man, the Work, and Its History". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 117 (6): 413–422. ISSN 0003-049X. https://www.jstor.org/stable/986460.

- Kennedy, E. S. (October 1966). "Late Medieval Planetary Theory". Isis 57 (3): 365–378. doi:10.1086/350144. ISSN 0021-1753. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/350144.

- Dabashi, Hamid. "Khwajah Nasir al-Din Tusi: The philosopher/vizier and the intellectual climate of his times". Routledge History of World Philosophies. Vol I. History of Islamic Philosophy. Seyyed Hossein Nasr and Oliver Leaman (eds.) London: Routledge. 1996. p. 529

- Siddiqi, Bakhtyar Husain. "Nasir al-Din Tusi". A History of Islamic Philosophy. Vol 1. M. M. Sharif (ed.). Wiesbaden:: Otto Harrossowitz. 1963. p. 565

- Virani, Shafique N. (2018-04-16). "Alamūt, Ismailism and Khwāja Qāsim Tushtarī's Recognizing God". Shii Studies Review 2 (1–2): 193–227. doi:10.1163/24682470-12340021. ISSN 2468-2462. http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/24682470-12340021.

- Virani, Shafique. "Hierohistory in Qāḍī l-Nuʿmān's Foundation of Symbolic Interpretation (Asās al-Taʾwīl): The Birth of Jesus" (in en). Studies in Islamic Historiography. doi:10.1163/9789004415294_007. https://www.academia.edu/41992496.

- Sharaf al-Din al-Muzaffar al-Tusi biography - MacTutor History of Mathematics http://www-history.mcs.st-and.ac.uk/Biographies/Al-Tusi_Sharaf.html

- Peter Willey, The Eagle's Nest: Ismaili Castles in Iran and Syria, (I.B. Tauris, 2005), 172.

- Farhad Daftari. "اسماعیلیان سدههای میانه در سرزمینهای ایران | The Institute of Ismaili Studies". http://akdn2stg.prod.acquia-sites.com/sites/default/files/The%20mediaeval%20Ismailis%20of%20the%20Iranian%20Lands%20-%20Farsi-103105894.pdf.

- Lagerlund, Henrik (2010) (in en). Encyclopedia of Medieval Philosophy: Philosophy Between 500 and 1500. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 825. ISBN 978-1-4020-9728-7.

- Michael Axworthy, A History of Iran: Empire of the Mind, (Basic Books, 2008), 104.

- Virani, Shafique N. (2007-04-01), "Salvation and Imamate", The Ismailis in the Middle Ages (Oxford University Press): pp. 165–182, doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195311730.003.0009, ISBN 978-0-19-531173-0, http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195311730.003.0009, retrieved 2020-11-17

- H. Daiber, F.J. Ragep, "Tusi" in Encyclopaedia of Islam. Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel and W.P. Heinrichs. Brill, 2007. Brill Online. Quote: "Tusi's prose writings, which number over 150 works, represent one of the largest collections by a single Islamic author. Writing in both Arabic and Persian, Nasir al-Din dealt with both religious ("Islamic") topics and non-religious or secular subjects ("the ancient sciences")."

- Seyyed Hossein Nasr. The Islamic Intellectual Tradition in Persia. Curson Press, 1996. See p. 208: "Nearly 150 treatises and letters by Nasir al-Din Tusi are known, of which 25 are in Persian and the rest in Arabic. There is even a treatise on geomancy which Tusi wrote in Arabic, Persian, and Turkish, demonstrating his mastery of all three languages."

- Lameer, Joep (29 April 2020). "A New Look at Ṭūsī's Awṣāf al-ashrāf". Journal of Islamic Manuscripts 11 (1): 1–27. doi:10.1163/1878464X-01101001. https://dx.doi.org/10.1163%2F1878464X-01101001

- Morris Rossabi (28 November 2014). From Yuan to Modern China and Mongolia: The Writings of Morris Rossabi. BRILL. pp. 281–. ISBN 978-90-04-28529-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=GXejBQAAQBAJ&pg=PA281.

- Shams al‐Dīn al‐Bukhārī at the Mathematics Genealogy Project https://www.genealogy.math.ndsu.nodak.edu/id.php?id=204293

- Nasir al-Din al-Tusi at the Mathematics Genealogy Project https://www.genealogy.math.ndsu.nodak.edu/id.php?id=201288

- Nasir al-Din al-Tusi at the Mathematics Genealogy Project https://www.genealogy.math.ndsu.nodak.edu/id.php?id=184632

- Craig G. Fraser, 'The cosmos: a historical perspective', Greenwood Publishing Group, 2006 p.39 https://books.google.com/books?id=3tJr_vl6rYsC&lpg=PA39&pg=PA39#v=onepage&q&f=false

- George Saliba, 'Al-Qushji's Reform of the Ptolemaic Model for Mercury', Arabic Sciences and Philosophy, v.3 1993, pp.161-203 http://www.tad.org.tr/wp-content/files/webfiles/alikuscu_makale_saliba.pdf

- George Saliba, 'Revisiting the Astronomical Contacts Between the World of Islam and Renaissance Europe: The Byzantine Connection', 'The occult sciences in Byzantium', 2006, p.368 https://books.google.com/books?id=muGVUiKEYccC&lpg=PA368&pg=PA368#v=onepage&q&f=false

- Ragep, F. Jamil (2001), "Freeing Astronomy from Philosophy: An Aspect of Islamic Influence on Science", Osiris 16, 2nd ser.: 49–64, doi:10.1086/649338, Bibcode: 2001Osir...16...49R, http://digitool.Library.McGill.CA:80/webclient/DeliveryManager?pid=156332&custom_att_2=direct , at p. 60.

- F. Jamil Ragep (2001), "Tusi and Copernicus: The Earth's Motion in Context", Science in Context 14 (1-2), p. 145–163. Cambridge University Press . https://www.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cambridge%20University%20Press

- Ragep, Jamil, Nasir al-Din Tusi’s Memoir on Astronomy (al-Tadhkira fi `ilm al-hay’ a) Edition, Translation, Commentary, and Introduction. 2 vols. Sources in the History of Mathematics and Physical Sciences. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1993. pp. 129

- O'Connor, J. J.; Robertson, E. F. (November 2002). "Galileo Galilei". University of St Andrews. http://www-gap.dcs.st-and.ac.uk/~history/Biographies/Galileo.html.

- Tony Street (July 23, 2008). "Arabic and Islamic Philosophy of Language and Logic". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/arabic-islamic-language.

- "trigonometry". Encyclopædia Britannica. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/605281/trigonometry. Retrieved 2011-04-25.

- * Katz, Victor J. (1993). A History of Mathematics: An Introduction, p259. Addison Wesley. ISBN:0-673-38039-4.

- Bosworth, Clifford E.; Asimov (2003). History of civilizations of Central Asia.. 4. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 190. ISBN 81-208-1596-3.

- Hayes, John R.; Badeau, John S. (1983). The genius of Arab civilization : source of Renaissance (2nd ed.). Taylor & Francis. p. 156. ISBN 0-262-08136-9.

- http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Al-Tusi_Nasir.html,"One of al-Tusi's most important mathematical contributions was the creation of trigonometry as a mathematical discipline in its own right rather than as just a tool for astronomical applications. In Treatise on the quadrilateral al-Tusi gave the first extant exposition of the whole system of plane and spherical trigonometry. This work is really the first in history on trigonometry as an independent branch of pure mathematics and the first in which all six cases for a right-angled spherical triangle are set forth"/

- Berggren, J. Lennart (2007). "Mathematics in Medieval Islam". The Mathematics of Egypt, Mesopotamia, China, India, and Islam: A Sourcebook. Princeton University Press. p. 518. ISBN 978-0-691-11485-9.

- Also the 'sine law' (of geometry and trigonometry, applicable to spherical trigonometry) is attributed, among others, to Alkhujandi. (The three others are Abul Wafa Bozjani, Nasiruddin Tusi, and Abu Nasr Mansur). Razvi, Syed Abbas Hasan (1991) A history of science, technology, and culture in Central Asia, Volume 1 University of Peshawar, Peshawar, Pakistan, page 358, OCLC 26317600 https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/26317600

- Bijli suggests that three mathematicians are in contention for the honor, Alkhujandi, Abdul-Wafa and Mansur, leaving out Nasiruddin Tusi. Bijli, Shah Muhammad and Delli, Idarah-i Adabiyāt-i (2004) Early Muslims and their contribution to science: ninth to fourteenth century Idarah-i Adabiyat-i Delli, Delhi, India, page 44, OCLC 66527483 https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/66527483

- Kirchner, E. (2013). "Color theory and color order in medieval Islam: A review". Color Research & Application 40 (1): 5-16. doi:10.1002/col.21861. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002%2Fcol.21861

- Smithson, H.E.; Dinkova-Bruun, G.; Gasper, G.E.M.; Huxtable, M.; McLeish, T.C.B.; Panti, C. (2012). "A three-dimensional color space from the 13th century". J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 29 (2): 346-352. doi:10.1364/josaa.29.00A346. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3287286

- Nasir ad-Din Tusi (1964) The Nasirean Ethics (translator: G.M. Wickens). London: Allen & Unwin, p. 44.

- Nasir ad-Din Tusi (1964) The Nasirean Ethics (translator: G.M. Wickens). London: Allen & Unwin, p. 45.

- Nasir ad-Din Tusi (1964) The Nasirean Ethics (translator: G.M. Wickens). London: Allen & Unwin, p. 45f.

- Nasir ad-Din Tusi (1964) The Nasirean Ethics (translator: G.M. Wickens). London: Allen & Unwin, p. 42 (emphasis added).

- Alakbarli, Farid (Summer 2001). "A 13th-Century Darwin? Tusi's Views on Evolution". Azerbaijan International 9 (2): 48–49. http://azer.com/aiweb/categories/magazine/92_folder/92_articles/92_tusi.html.

- Shoja, M.M.; Tubbs, R.S. (2007). "The history of anatomy in Persia". Journal of Anatomy 210 (4): 359–378. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2007.00711.x. PMID 17428200. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2100290

- Alakbarli, Farid (2001). "A 13th-Century Darwin? Tusi's Views on Evolution". Azerbaijan International 9 (2 (Summer 2001)): 48–49. https://azer.com/aiweb/categories/magazine/92_folder/92_articles/92_tusi.html. Retrieved 27 January 2018. "While this reasoning may seem backward to today's Western mind, some of Tusi's theories did have merit. For instance, Tusi believed that a body of matter is able to change, but is not able to entirely disappear. He wrote: 'A body of matter cannot disappear completely. It only changes its form, condition, composition, color and other properties and turns into a different complex or elementary matter'.".

- Freely, John (2011). Light from the East. doi:10.5040/9780755600007. ISBN 9780755600007. http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9780755600007.

- Freely, John (2011). Light from the East: How the Science of Medieval Islam Helped to Shape the Western World. I.B.Tauris. doi:10.5040/9780755600007. ISBN 978-0-7556-0000-7. https://www.bloomsburymedievalstudies.com/encyclopedia?docid=b-9780755600007.

- 2003ASPC..289..157B Page 157. Adsabs.harvard.edu. Bibcode: 2003ASPC..289..157B. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2003ASPC..289..157B

- 10269 tusi - Mano biblioteka - Google knygos. https://books.google.com/books?q=10269+tusi&hl=lt. Retrieved 2013-02-27.

- "Nasir al-Din al-Tusi's 812th Birthday". https://www.google.com/doodles/nasir-al-din-al-tusis-812th-birthday.

- "In Persian نگاه عربی به خواجه نصیرالدین طوسی در گوگل". 19 February 2013. http://www.bbc.co.uk/persian/science/2013/02/130219_l42_khaje_nasir_google.shtml.

- "مرکز تقويم موسسه ژئوفيزيک دانشگاه تهران". http://calendar.ut.ac.ir.

- Veselovsky, I. N. (1973-06-01). "Copernicus and Nasīr Al-DĪn AL-TŪSĪ" (in en). Journal for the History of Astronomy 4 (2): 128–130. doi:10.1177/002182867300400205. ISSN 0021-8286. https://doi.org/10.1177/002182867300400205.

- Blåsjö, Viktor (2014-04-15). "A Critique of the Arguments for Maragha Influence on Copernicus". Journal for the History of Astronomy 45 (2): 183–195. doi:10.1177/002182861404500203. ISSN 0021-8286. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/002182861404500203.

- Blasjo, V. N. E. (2018). "A rebuttal of recent arguments for Maragha influence on Copernicus" (in en). http://dspace.library.uu.nl/bitstream/handle/1874/374781/blasjo2.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

Location: Tus, Khurasan, Khwarzamid Empire