| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sirius Huang | -- | 1751 | 2022-11-18 01:40:47 |

Video Upload Options

Sarcopterygii (/ˌsɑːrkɒptəˈrɪdʒi.aɪ/; from grc σάρξ (sárx) 'flesh', and πτέρυξ (ptérux) 'wing, fins')—sometimes considered synonymous with Crossopterygii (from grc κροσσός (krossós) 'fringe')—is a taxon (traditionally a class or subclass) of the bony fishes whose members are known as lobe-finned fishes. The group Tetrapoda, a superclass including amphibians, reptiles (including dinosaurs and therefore birds), and mammals, evolved from certain sarcopterygians; under a cladistic view, tetrapods are themselves considered a group within Sarcopterygii. The known extant non-tetrapod sarcopterygians include two species of coelacanths and six species of lungfishes.

1. Characteristics

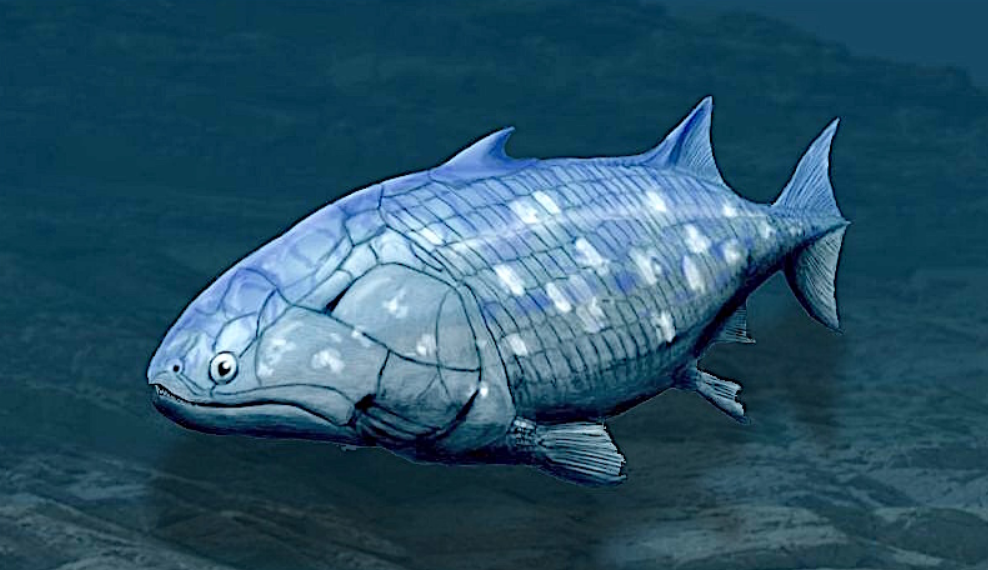

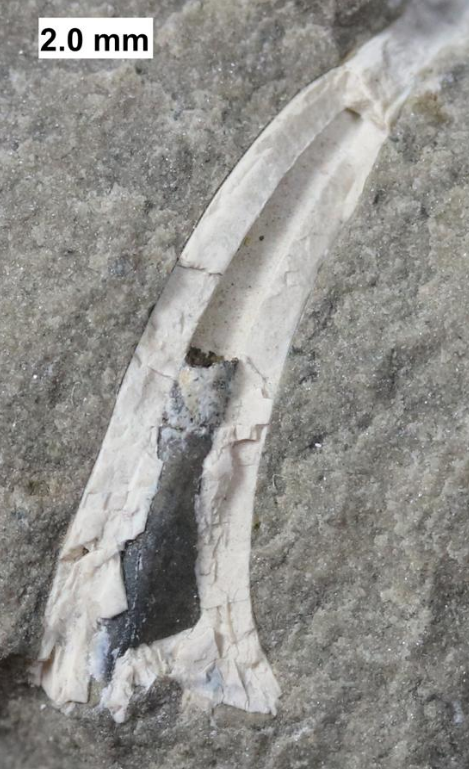

Early lobe-finned fishes are bony fish with fleshy, lobed, paired fins, which are joined to the body by a single bone.[5] The fins of lobe-finned fishes differ from those of all other fish in that each is borne on a fleshy, lobelike, scaly stalk extending from the body. The scales of sarcopterygians are true scaloids, consisting of lamellar bone surrounded by layers of vascular bone, dentine-like cosmine, and external keratin.[6] The morphology of tetrapodomorphs, fish that are similar-looking to tetrapods, give indications of the transition from water to terrestrial life.[7] Pectoral and pelvic fins have articulations resembling those of tetrapod limbs. The first tetrapod land vertebrates, basal amphibian organisms, possessed legs derived from these fins. Sarcopterygians also possess two dorsal fins with separate bases, as opposed to the single dorsal fin of actinopterygians (ray-finned fish). The braincase of sarcopterygians primitively has a hinge line, but this is lost in tetrapods and lungfish. Many early sarcopterygians have a symmetrical tail. All sarcopterygians possess teeth covered with true enamel.

Most species of lobe-finned fishes are extinct. The largest known lobe-finned fish was Rhizodus hibberti from the Carboniferous period of Scotland which may have exceeded 7 meters in length. Among the two groups of extant (living) species, the coelacanths and the lungfishes, the largest species is the West Indian Ocean coelacanth, reaching 2 m (6 ft 7 in) in length and weighing up 110 kg (240 lb). The largest lungfish is the African lungfish which can reach 2 m (6.6 ft) in length and weigh up to 50 kg (110 lb).[8][9]

2. Classification

Taxonomists who subscribe to the cladistic approach include the grouping Tetrapoda within this group, which in turn consists of all species of four-limbed vertebrates.[10] The fin-limbs of lobe-finned fishes such as the coelacanths show a strong similarity to the expected ancestral form of tetrapod limbs. The lobe-finned fishes apparently followed two different lines of development and are accordingly separated into two subclasses, the Rhipidistia (including the Dipnoi, the lungfish, and the Tetrapodomorpha which include the Tetrapoda) and the Actinistia (coelacanths).

2.1. Taxonomy

The classification below follows Benton (2004),[11] and uses a synthesis of rank-based Linnaean taxonomy and also reflects evolutionary relationships. Benton included the Superclass Tetrapoda in the Subclass Sarcopterygii in order to reflect the direct descent of tetrapods from lobe-finned fish, despite the former being assigned a higher taxonomic rank.[11]

| Actinistia |  |

Actinistia, coelacanths, are a subclass of lobe-finned fishes, all but two of which are fossil species. The subclass Actinistia contains the coelacanths, including the two living coelacanths: the West Indian Ocean coelacanth and the Indonesian coelacanth. |

|---|---|---|

| Dipnoi |  |

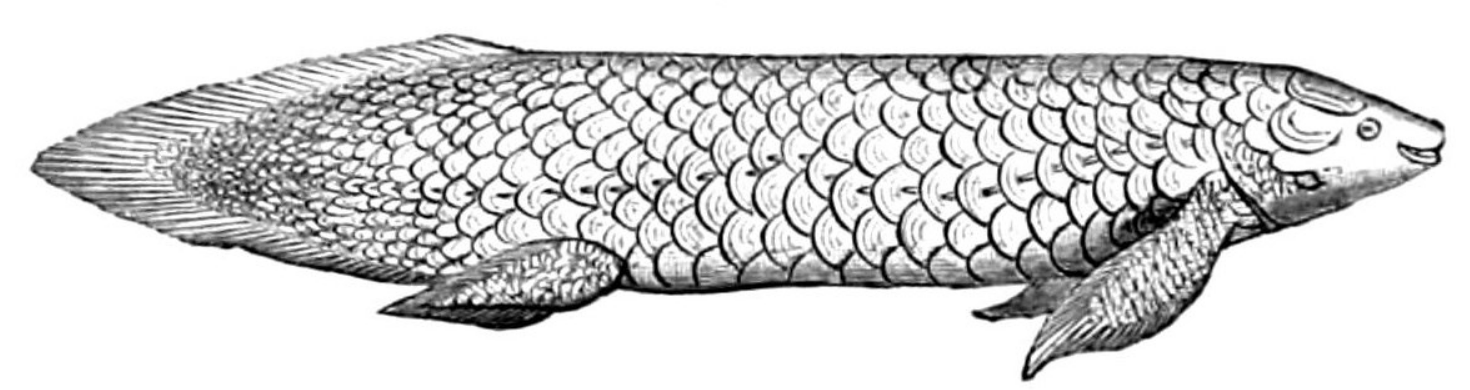

Dipnoi, lungfish, also known as salamanderfish,[12] are a subclass of freshwater fish. Lungfish are best known for retaining characteristics primitive within the bony fishes, including the ability to breathe air, and structures primitive within the lobe-finned fishes, including the presence of lobed fins with a well-developed internal skeleton. Today, lungfish live only in Africa, South America, and Australia . While vicariance would suggest this represents an ancient distribution limited to the Mesozoic supercontinent Gondwana, the fossil record suggests advanced lungfish had a widespread freshwater distribution and the current distribution of modern lungfish species reflects extinction of many lineages following the breakup of Pangaea, Gondwana, and Laurasia. |

| Tetrapodomorpha |  |

Tetrapodomorpha, tetrapods and their extinct relatives, are a clade of vertebrates consisting of tetrapods (four-limbed vertebrates) and their closest sarcopterygian relatives that are more closely related to living tetrapods than to living lungfish.[13] Advanced forms transitional between fish and the early labyrinthodonts, like Tiktaalik, have been referred to as "fishapods" by their discoverers, being half-fish, half-tetrapods, in appearance and limb morphology. The Tetrapodomorpha contain the crown group tetrapods (the last common ancestor of living tetrapods and all of its descendants) and several groups of early stem tetrapods, and several groups of related lobe-finned fishes, collectively known as the osteolepiforms. The Tetrapodamorpha minus the crown group Tetrapoda are the stem tetrapoda, a paraphyletic unit encompassing the fish to tetrapod transition. Among the characters defining tetrapodomorphs are modifications to the fins, notably a humerus with convex head articulating with the glenoid fossa (the socket of the shoulder joint). Tetrapodomorph fossils are known from the early Devonian onwards, and include Osteolepis, Panderichthys, Kenichthys, and Tungsenia.[14] |

- Subclass Sarcopterygii

- †Order Onychodontida

- Order Actinistia

- Infraclass Dipnomorpha

- †Order Porolepiformes

- Subclass Dipnoi

- Order Ceratodontiformes

- Order Lepidosireniformes

- Infraclass Tetrapodomorpha

- †Order Rhizodontida

- Superorder Osteolepidida

- †Order Osteolepiformes

- †Family Tristichopteridae

- †Order Panderichthyida

- Superclass Tetrapoda

- †Order Osteolepiformes

2.2. Phylogeny

The cladogram presented below is based on studies compiled by Janvier et al. (1997) for the Tree of Life Web Project,[15] Mikko's Phylogeny Archive[16] and Swartz (2012).[17]

- Sarcopterygii incertae sedis

- †Guiyu oneiros Zhu et al., 2009

- †Diabolepis speratus (Chang & Yu, 1984)

- †Langdenia campylognatha Janvier & Phuong, 1999

- †Ligulalepis Schultze, 1968

- †Meemannia eos Zhu, Yu, Wang, Zhao & Jia, 2006

- †Psarolepis romeri Yu 1998 sensu Zhu, Yu, Wang, Zhao & Jia, 2006

- †Megamastax ambylodus Choo, Zhu, Zhao, Jia, & Zhu, 2014

- †Sparalepis tingi Choo, Zhu, Qu, Yu, Jia & Zhaoh, 2017[18][19]

- paraphyletic Osteolepida incertae sedis|[20]

- †Bogdanovia orientalis Obrucheva 1955 [has been treated as Coelacanthinimorph sarcopterygian]

- †Canningius groenlandicus Säve-Söderbergh, 1937

- †Chrysolepis

- †Geiserolepis

- †Latvius

- †L. grewingki (Gross, 1933)

- †L. porosus Jarvik, 1948

- †L. obrutus Vorobyeva, 1977

- †Lohsania utahensis Vaughn, 1962

- †Megadonichthys kurikae Vorobyeva, 1962

- †Platyethmoidia antarctica Young, Long & Ritchie, 1992

- †Shirolepis ananjevi Vorobeva, 1977

- †Sterropterygion brandei Thomson, 1972

- †Thaumatolepis edelsteini Obruchev, 1941

- †Thysanolepis micans Vorobyeva, 1977

- †Vorobjevaia dolonodon Young, Long & Ritchie, 1992

- paraphyletic Elpistostegalia/Panderichthyida incertae sedis

- †Parapanderichthys stolbovi (Vorobyeva, 1960) Vorobyeva, 1992

- †Howittichthys warrenae Long & Holland, 2008

- †Livoniana multidentata Ahlberg, Luksevic & Mark-Kurik, 2000

- Stegocephalia incertae sedis

- †Antlerpeton clarkii Thomson, Shubin & Poole, 1998

- †Austrobrachyops jenseni Colbert & Cosgriff, 1974

- †Broilisaurus raniceps (Goldenberg, 1873) Kuhn, 1938

- †Densignathus rowei Daeschler, 2000

- †Doragnathus woodi Smithson, 1980

- †Jakubsonia livnensis Lebedev, 2004

- †Limnerpeton dubium Fritsch, 1901 (nomen dubium)

- †Limnosceloides Romer, 1952

- †L. dunkardensis Romer, 1952 (Type)

- †L. brahycoles Langston, 1966

- †Occidens portlocki Clack & Ahlberg, 2004

- †Ossinodus puerorum emend Warren & Turner, 2004

- †Romeriscus periallus Baird & Carroll, 1968

- †Sigournea multidentata Bolt & Lombard, 2006

- †Sinostega pani Zhu et al., 2002

- †Ymeria denticulata Clack et al., 2012

3. Evolution

Lobe-finned fishes (sarcopterygians) and their relatives the ray-finned fishes (actinopterygians) comprise the superclass of bony fishes (Osteichthyes) characterized by their bony skeleton rather than cartilage. There are otherwise vast differences in fin, respiratory, and circulatory structures between the Sarcopterygii and the Actinopterygii, such as the presence of cosmoid layers in the scales of sarcopterygians. The earliest fossils of sarcopterygians were found in the uppermost Silurian, about 418 Ma (million years ago). They closely resembled the acanthodians (the "spiny fish", a taxon that became extinct at the end of the Paleozoic). In the early–middle Devonian (416–385 Ma), while the predatory placoderms dominated the seas, some sarcopterygians came into freshwater habitats.

In the Early Devonian (416–397 Ma), the sarcopterygians split into two main lineages: the coelacanths and the rhipidistians. Coelacanths never left the oceans and their heyday was the late Devonian and Carboniferous, from 385 to 299 Ma, as they were more common during those periods than in any other period in the Phanerozoic. Coelacanths of the genus Latimeria still live today in the open (pelagic) oceans.

The Rhipidistians, whose ancestors probably lived in the oceans near the river mouths (estuaries), left the ocean world and migrated into freshwater habitats. In turn, they split into two major groups: lungfish and the tetrapodomorphs. Lungfish radiated into their greatest diversity during the Triassic period; today fewer than a dozen genera remain. They evolved the first proto-lungs and proto-limbs, adapting to living outside a submerged water environment by the middle Devonian (397–385 Ma).

3.1. Hypotheses for Means of Pre-Adaption

There are three major hypotheses as to how lungfish evolved their stubby fins (proto-limbs).

- Shrinking waterhole

- The first, traditional explanation is the "shrinking waterhole hypothesis", or "desert hypothesis", posited by the American paleontologist Alfred Romer, who believed that limbs and lungs may have evolved from the necessity of having to find new bodies of water as old waterholes dried up.[21]

- Inter-tidal adaption

- Niedźwiedzki, Szrek, Narkiewicz, et al. (2010)[22] proposed a second, the "inter-tidal hypothesis": That sarcopterygians may have first emerged unto land from intertidal zones rather than inland bodies of water, based on the discovery of the 395 million-year-old Zachełmie tracks in Zachełmie, Świętokrzyskie Voivodeship, Poland , the oldest discovered fossil evidence of tetrapods.[22][23]

- Woodland swamp adaption

- Retallack (2011)[24] proposed a third hypothesis is dubbed the "woodland hypothesis": Retallack argues that limbs may have developed in shallow bodies of water, in woodlands, as a means of navigating in environments filled with roots and vegetation. He based his conclusions on the evidence that transitional tetrapod fossils are consistently found in habitats that were formerly humid and wooded floodplains.[21][24]

- Habitual escape onto land

- A fourth, minority hypothesis posits that advancing onto land achieved more safety from predators, less competition for prey, and certain environmental advantages not found in water—such as oxygen concentration,[25] and temperature control[26]—implying that organisms developing limbs were also adapting to spending some of their time out of water. However, studies have found that sarcopterygians developed tetrapod-like limbs suitable for walking well before venturing onto land.[27] This suggests they adapted to walking on the ground-bed under water before they advanced onto dry land.

3.2. History Through to the End-Permian Extinction

The first tetrapodomorphs, which included the gigantic rhizodonts, had the same general anatomy as the lungfish, who were their closest kin, but they appear not to have left their water habitat until the late Devonian epoch (385–359 Ma), with the appearance of tetrapods (four-legged vertebrates). Tetrapods are the only tetrapodomorphs which survived after the Devonian.

Non-tetrapod sarcopterygians continued until towards the end of Paleozoic era, suffering heavy losses during the Permian–Triassic extinction event (251 Ma).

References

- Zhao, W.; Zhang, X.; Jia, G.; Shen, Y.; Zhu, M. (2021). "The Silurian-Devonian boundary in East Yunnan (South China) and the minimum constraint for the lungfish-tetrapod split". Science China Earth Sciences 64 (10): 1784–1797. doi:10.1007/s11430-020-9794-8. Bibcode: 2021ScChD..64.1784Z. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/353479392.

- Zhu, M.; Zhao, W.; Jia, L.; Lu, J.; Qiao, T.; Qu, Q. (2009). "The oldest articulated osteichthyan reveals mosaic gnathostome characters". Nature 458 (7237): 469–474. doi:10.1038/nature07855. PMID 19325627. Bibcode: 2009Natur.458..469Z. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038%2Fnature07855

- Coates, M.I. (2009). "Palaeontology: Beyond the age of fishes". Nature 458 (7237): 413–414. doi:10.1038/458413a. PMID 19325614. Bibcode: 2009Natur.458..413C. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038%2F458413a

- "Pharyngula – Guiyu oneiros". 1 April 2009. http://scienceblogs.com/pharyngula/2009/04/guiyu_oneiros.php.

- Clack, J.A. (2002). Gaining Ground. Indiana University.

- Kardong, Kenneth V. (1998). Vertebrates: Comparative anatomy, function, evolution (second ed.). USA: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-115356-X. ISBN:0-697-28654-1

- Clack, J.A. (2009). "The fin to limb transition: New data, interpretations, and hypotheses from paleontology and developmental biology". Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 37 (1): 163–179. doi:10.1146/annurev.earth.36.031207.124146. Bibcode: 2009AREPS..37..163C. https://dx.doi.org/10.1146%2Fannurev.earth.36.031207.124146

- Froese, Rainer, and Daniel Pauly, eds. (2009). "Lepidosirenidae" in FishBase. January 2009 version. http://www.fishbase.org/Summary/FamilySummary.php?Family=Lepidosirenidae

- "Protopterus aethiopicus". http://fishing-worldrecords.com/lung%20fishes/Protopterus%20aethiopicus.html.

- Nelson, Joseph S. (2006). Fishes of the World. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-25031-9.

- Benton, M.J. (2004). Vertebrate Paleontology (3rd ed.). Blackwell Science.

- The History of Creation, or, the Development of the Earth and Its Inhabitants by the Action of Natural Causes (8th, German ed.). D. Appleton. 1892. p. 289. https://books.google.com/books?id=ltUj8vk3auEC. "A popular exposition of the doctrine of evolution in general, and of that of Darwin, Goethe, and Lamarck in particular."

- Amemiya, C.T. et al. (2013). "The African coelacanth genome provides insights into tetrapod evolution". Nature 496 (7445): 311–316. doi:10.1038/nature12027. PMID 23598338. Bibcode: 2013Natur.496..311A. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3633110

- Lu, Jing; Zhu, Min; Long, John A.; Zhao, Wenjin; Senden, Tim J.; Jia, Liantao; Qiao, Tuo (2012). "The earliest known stem-tetrapod from the lower Devonian of China". Nature Communications 3: 1160. doi:10.1038/ncomms2170. PMID 23093197. Bibcode: 2012NatCo...3.1160L. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038%2Fncomms2170

- Janvier, Philippe (1997-01-01). "Vertebrata: Animals with backbones". The Tree of Life Web Project. http://tolweb.org/Vertebrata/14829/1997.01.01.

- Haaramo, Mikko (2003). "Sarcopterygii". University of Helsinki. http://www.helsinki.fi/~mhaaramo/metazoa/deuterostoma/chordata/sarcopterygii/sarcopterygii_1.html.

- Swartz, B. (2012). "A marine stem-tetrapod from the Devonian of western North America". PLOS ONE 7 (3): e33683. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0033683. PMID 22448265. Bibcode: 2012PLoSO...733683S. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3308997

- Choo, Brian; Zhu, Min; Qu, Qingming; Yu, Xiaobo; Jia, Liantao; Zhao, Wenjin (2017-03-08). "A new osteichthyan from the late Silurian of Yunnan, China". PLOS ONE 12 (3): e0170929. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0170929. ISSN 1932-6203. PMID 28273081. Bibcode: 2017PLoSO..1270929C. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=5342173

- Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter exited with status 1.

- The Osteolepida taxa were not addressed by Ahlberg & Johanson (1998).Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter exited with status 1.

- "Fish-tetrapod transition got a new hypothesis in 2011". Science 2.0. 27 December 2011. http://www.science20.com/news_articles/fishtetrapod_transition_got_new_hypothesis_2011-85782.

- Niedźwiedzki, Grzegorz; Szrek, Piotr; Narkiewicz, Katarzyna; Narkiewicz, Marek; Ahlberg, Per E. (2010). "Tetrapod trackways from the early Middle Devonian period of Poland". Nature 463 (7277): 43–48. doi:10.1038/nature08623. PMID 20054388. Bibcode: 2010Natur.463...43N. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038%2Fnature08623

- Barley, Shanta (6 January 2010). "Oldest footprints of a four-legged vertebrate discovered". New Scientist. https://www.newscientist.com/article/dn18346-oldest-footprints-of-a-fourlegged-vertebrate-discovered.html. Retrieved 3 January 2010.

- "Woodland hypothesis for Devonian tetrapod evolution". Journal of Geology (University of Chicago Press) 119 (3): 235–258. May 2011. doi:10.1086/659144. Bibcode: 2011JG....119..235R. https://dx.doi.org/10.1086%2F659144

- Carroll, Irwin, & Green (2005),[24] cited in[25]

- Clack (2007),[27] cited in[25]

- King (2011),[29] cited in[30]