| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Camila Xu | -- | 1849 | 2022-11-18 01:30:38 |

Video Upload Options

Alvin Plantinga's free will defense is a logical argument developed by American analytic philosopher Alvin Plantinga, the John A. O'Brien Professor of Philosophy Emeritus at the University of Notre Dame, and published in its final version in his 1977 book God, Freedom, and Evil. Plantinga's argument is a defense against the logical problem of evil as formulated by philosopher J. L. Mackie beginning in 1955. Mackie's formulation of the logical problem of evil argued that three attributes of God, omniscience, omnipotence, and omnibenevolence, in orthodox Christian theism are logically incompatible with the existence of evil. In 1982, Mackie conceded that Plantinga's defense successfully refuted his argument in The Miracle of Theism, though he did not claim that the problem of evil had been put to rest.

1. Mackie's Logical Argument from Evil

The logical argument from evil argued by J. L. Mackie, and to which the free will defense responds, is an argument against the existence of the Christian God based on the idea that a logical contradiction exists between four theological tenets in orthodox Christian theology. Specifically, the argument from evil asserts that the following set of propositions are, by themselves, logically inconsistent or contradictory:

- God is omniscient (all-knowing)

- God is omnipotent (all-powerful)

- God is omnibenevolent (morally perfect)

- There is evil in the world

Most orthodox Christian theologians agree with the first three propositions describing God as all-knowing (1), all-powerful (2), and morally perfect (3), and agree with the proposition that there is evil in the world, as described in proposition (4). The logical argument from evil asserts that a God with the attributes (1-3), must know about all evil, would be capable of preventing it, and as morally perfect would be motivated to do so.[1][2] The argument from evil concludes that the existence of the orthodox Christian God is, therefore, incompatible with the existence of evil and can be logically ruled out.

2. Plantinga's Free Will Defense

Plantinga's free will defense begins by asserting that Mackie's argument failed to establish an explicit logical contradiction between God and the existence of evil. In other words Plantinga shows that (1-4) are not on their own contradictory, and that any contradiction must originate from an atheologian's implicit unstated assumptions, assumptions representing premises not stated in the argument itself. With an explicit contradiction ruled out, an atheologian must add premises to the argument for it to succeed.[3] Nonetheless, if Plantinga had offered no further argument then an atheologian's intuitive impressions that a contradiction must exist would have remained unanswered. Plantinga sought to resolve this by offering two further points.[3]

First, Plantinga pointed out that God, though omnipotent, could not be expected to do literally anything. God could not, for example, create square circles, act contrary to his nature, or, more relevantly, create beings with free will that would never choose evil.[3] Taking this latter point further, Plantinga argued that the moral value of human free will is a credible offsetting justification that God could have as a morally justified reason for permitting the existence of evil.[3] Plantinga did not claim to have shown that the conclusion of the logical problem is wrong, nor did he assert that God's reason for allowing evil is, in fact, to preserve free will. Instead, his argument sought only to show that the logical problem of evil was unsound.[3]

Plantinga's defense has received strong support among Christian academic philosophers and theologians.[4][5][6][7][8][9][10] Contemporary atheologians[11][12][13][14] have presented arguments claiming to have found the additional premises needed to create an explicitly contradictory theistic set by adding to the propositions 1-4. These arguments have not yet gained wider academic philosophical support.[15][16][17]

In addition to Plantinga's free will defense, there are other arguments purporting to undermine or disprove the logical argument from evil.[6] Plantinga's free will defense is the best known of these responses at least in part because of his thoroughness in describing and addressing the relevant questions and issues in God, Freedom, and Evil.[16]

3. Further Details

As opposed to a theodicy (a justification for God's actions), Plantinga puts forth a defense, offering a new proposition that is intended to demonstrate that it is logically possible for an omnibenevolent, omnipotent and omniscient God to create a world that contains moral evil. Significantly, Plantinga does not need to assert that his new proposition is true, merely that it is logically valid. In this way Plantinga's approach differs from that of a traditional theodicy, which would strive to show not just that the new propositions are valid, but that the argument is sound, prima facie plausible, or that there are good grounds for making it.[18] Thus the burden of proof on Plantinga is lessened, and yet his approach may still serve as a defense against the claim by Mackie that the simultaneous existence of evil and an omnipotent and omnibenevolent God is "positively irrational".[19]

As Plantinga summarised his defense:[20][21]

A world containing creatures who are significantly free (and freely perform more good than evil actions) is more valuable, all else being equal, than a world containing no free creatures at all. Now God can create free creatures, but He can't cause or determine them to do only what is right. For if He does so, then they aren't significantly free after all; they do not do what is right freely. To create creatures capable of moral good, therefore, He must create creatures capable of moral evil; and He can't give these creatures the freedom to perform evil and at the same time prevent them from doing so. As it turned out, sadly enough, some of the free creatures God created went wrong in the exercise of their freedom; this is the source of moral evil. The fact that free creatures sometimes go wrong, however, counts neither against God's omnipotence nor against His goodness; for He could have forestalled the occurrence of moral evil only by removing the possibility of moral good.

Plantinga's argument is that even though God is omnipotent, it is possible that it was not in his power to create a world containing moral good but no moral evil; therefore, there is no logical inconsistency involved when God, although wholly good, creates a world of free creatures who choose to do evil.[22] The argument relies on the following propositions:

- There are possible worlds that even an omnipotent being can not actualize.

- A world with morally free creatures producing only moral good is such a world.

Plantinga refers to the first statement as "Leibniz's lapse" as the opposite was assumed by Leibniz.[23] The second proposition is more contentious. Plantinga rejects the compatibilist notion of freedom whereby God could directly cause agents to only do good without sacrificing their freedom. Although it would contradict a creature's freedom if God were to cause, or in Plantinga's terms strongly actualize, a world where creatures only do good, an omniscient God would still know the circumstances under which creatures would go wrong. Thus, God could avoid creating such circumstances, thereby weakly actualizing a world with only moral good. Plantinga's crucial argument is that this possibility may not be available to God because all possible morally free creatures suffer from "transworld depravity".

4. Reception

According to Chad Meister, professor of philosophy at Bethel College, most philosophers accept Plantinga's free will defense and thus see the logical problem of evil as having been sufficiently rebutted.[7] Robert Adams says that "it is fair to say that Plantinga has solved this problem. That is, he has argued convincingly for the consistency of God and evil."[8] William Alston has said that "Plantinga [...] has established the possibility that God could not actualize a world containing free creatures that always do the right thing."[9] William L. Rowe has written "granted incompatibilism, there is a fairly compelling argument for the view that the existence of evil is logically consistent with the existence of the theistic God", referring to Plantinga's argument.[24]

In Arguing about Gods, Graham Oppy offers a dissent, acknowledging that "[m]any philosophers seem to suppose that [Plantinga's free will defense] utterly demolishes the kinds of 'logical' arguments from evil developed by Mackie" but continuing "I am not sure this is a correct assessment of the current state of play".[25] Concurring with Oppy, A.M. Weisberger writes “contrary to popular theistic opinion, the logical form of the argument is still alive and beating.”[26] Among contemporary philosophers, most discussion on the problem of evil presently revolves around the evidential problem of evil, namely that the existence of God is unlikely, rather than illogical.[27]

5. Additional Objections and Responses

5.1. Incompatibilist View of Free Will

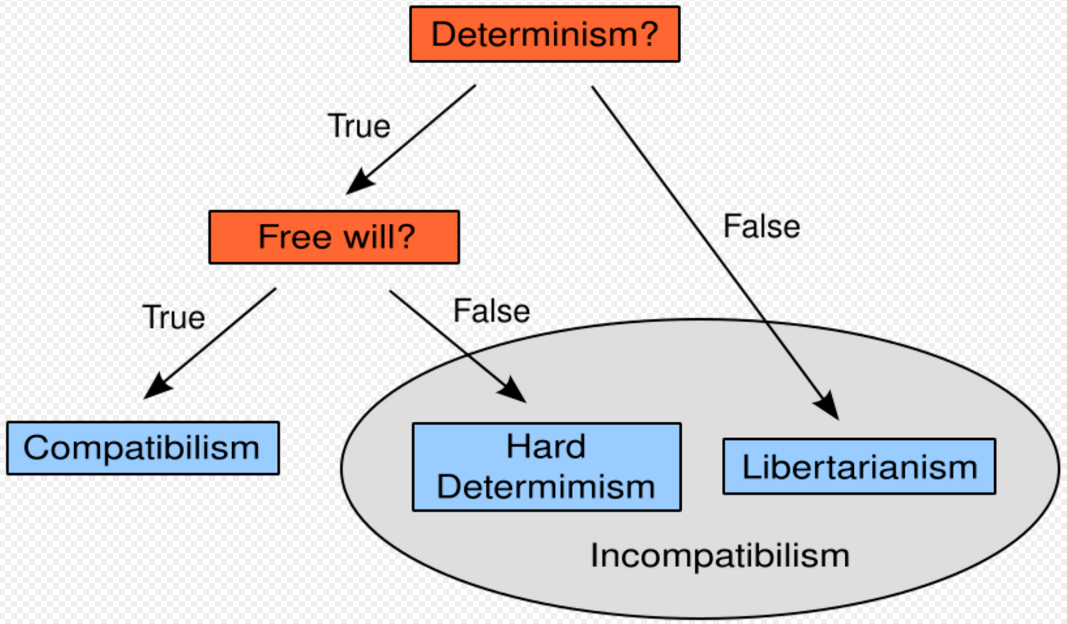

Critics of Plantinga's argument, such as philosopher Antony Flew, have responded that it presupposes a libertarian, incompatibilist view of free will (free will and determinism are metaphysically incompatible), while their view is a compatibilist view of free will (free will and determinism, whether physical or divine, are metaphysically compatible).[28][29] The view of compatibilists is that God could have created a world containing moral good but no moral evil. In such a world people could have chosen to only perform good deeds, even though all their choices were predestined.[22]

Plantinga dismisses compatibilism, stating "this objection... seems utterly implausible. One might as well claim that being in jail doesn't really limit one's freedom on the grounds that if one were not in jail, he'd be free to come and go as he pleased".[30]

5.2. Transworld Depravity

Plantinga's idea of weakly actualizing a world can be viewed as having God actualizing a subset of the world, letting the free choices of creatures complete the world. Therefore, it is certainly possible that a person completes the world by only making morally good choices; that is, there exist possible worlds where a person freely chooses to do no moral evil. However, it may be the case that for each such world, there is some morally significant choice that this person would do differently if these circumstances were to occur in the actual world. In other words, each such possible world contains a world segment, meaning everything about that world up to the point where the person must make that critical choice, such that if that segment was part of the actual world, the person would instead go wrong in completing that world. Formally, transworld depravity is defined as follows:[31]

Less formally: Consider all possible (not actual) worlds in which someone always chooses the right. In all those, there will be a subpart of the world that says that person was free to choose a certain right or wrong action, but does not say whether they chose it. If that subpart were actual (in the real world), then they would choose the wrong.

Plantinga responds that "What is important about the idea of transworld depravity is that if a person suffers from it, then it wasn't within God's power to actualize any world in which that person is significantly free but does no wrong—that is, a world in which he produces moral good but no moral evil"[31] and that it is logically possible that every person suffers from transworld depravity.[32]

References

- Mackie, J. L. (1955). "Evil and Omnipotence". Mind 64: 200–12.

- McCloskey, H. J. (1960). "God and Evil". Philosophical Quarterly 10: 97–114.

- Plantinga, Alvin (1977). God, Freedom, and Evil. Grand Rapids, MI:: Eerdmans. pp. Chapter 4. ISBN 0-8028-1731-9.

- "It used to be widely held by philosophers that God and evil are incompatible. Not any longer. Alvin Plantinga's Free Will Defense is largely responsible for this shift."Howard-Snyder, Daniel; John O’Leary-Hawthorne (1999). "Transworld Sanctity and Plantinga's Free Will Defense". International Journal for the Philosophy of Religion 16 (3): 336–351. http://commonsenseatheism.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/02/Howard-Snyder-Transworld-Sanctity-and-Plantingas-Free-Will-Defense.pdf. Retrieved 2013-09-12.

- "Most philosophers have agreed that the free will defense has defeated the logical problem of evil. [...] Because of [Plantinga's argument], it is now widely accepted that the logical problem of evil has been sufficiently rebutted." Meister 2009, p. 134

- Craig, William Lane. "The problem of evil". http://www.reasonablefaith.org/the-problem-of-evil. "Therefore, I’m very pleased to be able to report that it is widely agreed among contemporary philosophers that the logical problem of evil has been dissolved. The co-existence of God and evil is logically possible."

- Meister 2009, p. 134

- Howard-Snyder & O'Leary-Hawthorne 1998, p. 1

- Alston 1991, p. 49

- Peterson et al. 1991, p. 133

- LaFollette, Hugh (1980). "Plantinga on the Free Will Defense". International Journal for Philosophy of Religion: 123–32. http://www.hughlafollette.com/papers/Plantinga_on_the_Free_Will_Defense.pdf. Retrieved 11 September 2013.

- Bradley, Raymond D.. "The Free Will Defense Refuted and God's Existence Disproved". http://www.infidels.org/library/modern/raymond_bradley/fwd-refuted.html. Retrieved 11 September 2013.

- Bergmann, Michael (1999). "Might-Counterfactuals, Transworld Untrustworthiness, and Plantinga's Free Will Defense". Faith and Philosophy 16 (3): 336–351. doi:10.5840/faithphil199916332. https://dx.doi.org/10.5840%2Ffaithphil199916332

- Howard-Snyder, Daniel; John Hawthorne (1998). "Transworld Sanctity and Plantinga's Free Will Defense". Int'l. Journal for Philosophy of Religion 44: 1–21.

- Craig, William Lane. "Logical Problem of Evil". http://www.reasonablefaith.org/the-problem-of-evil. "I’m very pleased to be able to report that it is widely agreed among contemporary philosophers that the logical problem of evil has been dissolved. The co-existence of God and evil is logically possible."

- "Logical Problem of Evil". http://www.iep.utm.edu/evil-log/. "But if the atheist means there’s some implicit contradiction between God and evil, then he must be assuming some hidden premises which bring out this implicit contradiction. But the problem is that no philosopher has ever been able to identify such premises. Therefore, the logical problem of evil fails to prove any inconsistency between God and evil."

- Craig, William Lane. "The Problem of Evil". http://www.reasonablefaith.org/the-problem-of-evil. "But if the atheist means there’s some implicit contradiction between God and evil, then he must be assuming some hidden premises which bring out this implicit contradiction. But the problem is that no philosopher has ever been able to identify such premises. Therefore, the logical problem of evil fails to prove any inconsistency between God and evil."

- Surin 1995, p. 193

- Mackie 1955, p. 200

- Plantinga 1974, pp. 166–167

- Plantinga 1977, p. 30

- Peterson et al. 1991, pp. 130–133

- Plantinga 1977, pp. 33–34

- Rowe 1979, p. 335

- Oppy 2006, pp. 262–263

- Weisberger 1999, p. 39

- Beebe 2005

- Mackie 1962

- Flew 1973

- Plantinga 1977, p. 32

- Plantinga 1977, p. 48

- Plantinga 1977, p. 53