| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dean Liu | -- | 5896 | 2022-11-10 01:40:58 |

Video Upload Options

Synesthesia (American English) or synaesthesia (British English) is a perceptual phenomenon in which stimulation of one sensory or cognitive pathway leads to involuntary experiences in a second sensory or cognitive pathway. People who report a lifelong history of such experiences are known as synesthetes. Awareness of synesthetic perceptions varies from person to person. In one common form of synesthesia, known as grapheme–color synesthesia or color–graphemic synesthesia, letters or numbers are perceived as inherently colored. In spatial-sequence, or number form synesthesia, numbers, months of the year, or days of the week elicit precise locations in space (e.g., 1980 may be "farther away" than 1990), or may appear as a three-dimensional map (clockwise or counterclockwise). Synesthetic associations can occur in any combination and any number of senses or cognitive pathways. Little is known about how synesthesia develops. It has been suggested that synesthesia develops during childhood when children are intensively engaged with abstract concepts for the first time. This hypothesis – referred to as semantic vacuum hypothesis – could explain why the most common forms of synesthesia are grapheme–color, spatial sequence, and number form. These are usually the first abstract concepts that educational systems require children to learn. Difficulties have been recognized in adequately defining synesthesia. Many different phenomena have been included in the term synesthesia, and in many cases the terminology seems to be inaccurate. A more accurate but less common term may be ideasthesia. The earliest recorded case of synesthesia is attributed to the Oxford University academic and philosopher John Locke, who, in 1690, made a report about a blind man who said he experienced the color scarlet when he heard the sound of a trumpet. However, there is disagreement as to whether Locke described an actual instance of synesthesia or was using a metaphor. The first medical account came from German physician Georg Tobias Ludwig Sachs in 1812. The term is from the Ancient Greek σύν syn, 'together', and αἴσθησις aisthēsis, 'sensation'.

1. Types

There are two overall forms of synesthesia:

- projective synesthesia: seeing colors, forms, or shapes when stimulated (the widely understood version of synesthesia)

- associative synesthesia: feeling a very strong and involuntary connection between the stimulus and the sense that it triggers

For example, in chromesthesia (sound to color), a projector may hear a trumpet, and see an orange triangle in space, while an associator might hear a trumpet, and think very strongly that it sounds "orange".

Synesthesia can occur between nearly any two senses or perceptual modes, and at least one synesthete, Solomon Shereshevsky, experienced synesthesia that linked all five senses.[1] Types of synesthesia are indicated by using the notation x → y, where x is the "inducer" or trigger experience, and y is the "concurrent" or additional experience. For example, perceiving letters and numbers (collectively called graphemes) as colored would be indicated as grapheme-color synesthesia. Similarly, when synesthetes see colors and movement as a result of hearing musical tones, it would be indicated as tone → (color, movement) synesthesia.

While nearly every logically possible combination of experiences can occur, several types are more common than others.

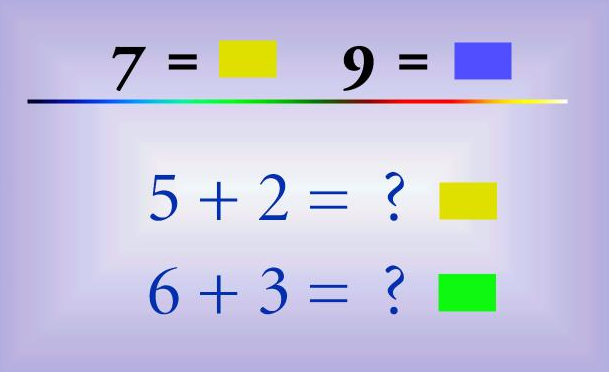

1.1. Grapheme–Color Synesthesia

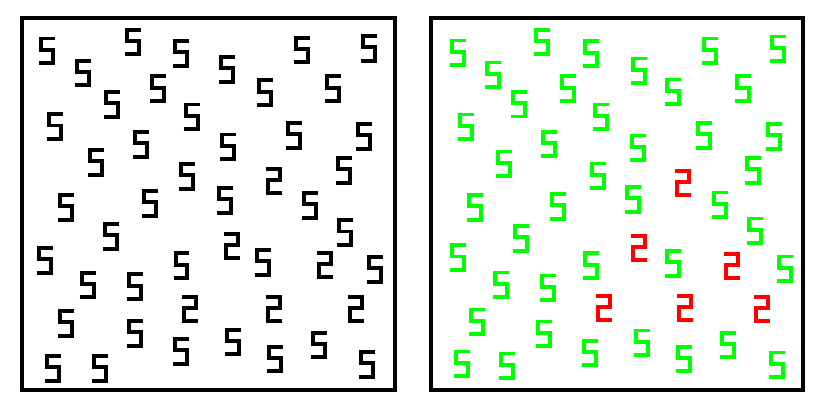

In one of the most common forms of synesthesia, individual letters of the alphabet and numbers (collectively referred to as "graphemes") are "shaded" or "tinged" with a color. While different individuals usually do not report the same colors for all letters and numbers, studies with large numbers of synesthetes find some commonalities across letters (e.g., A is likely to be red).[3]

1.2. Chromesthesia

Another common form of synesthesia is the association of sounds with colors. For some, everyday sounds can trigger seeing colors. For others, colors are triggered when musical notes or keys are being played. People with synesthesia related to music may also have perfect pitch because their ability to see and hear colors aids them in identifying notes or keys.[4]

The colors triggered by certain sounds, and any other synesthetic visual experiences, are referred to as photisms.

According to Richard Cytowic,[2] chromesthesia is "something like fireworks": voice, music, and assorted environmental sounds such as clattering dishes or dog barks trigger color and firework shapes that arise, move around, and then fade when the sound ends. Sound often changes the perceived hue, brightness, scintillation, and directional movement. Some individuals see music on a "screen" in front of their faces. For Deni Simon, music produces waving lines "like oscilloscope configurations – lines moving in color, often metallic with height, width, and, most importantly, depth. My favorite music has lines that extend horizontally beyond the 'screen' area."

Individuals rarely agree on what color a given sound is. Composers Franz Liszt and Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov famously disagreed on the colors of musical keys.

1.3. Spatial Sequence Synesthesia

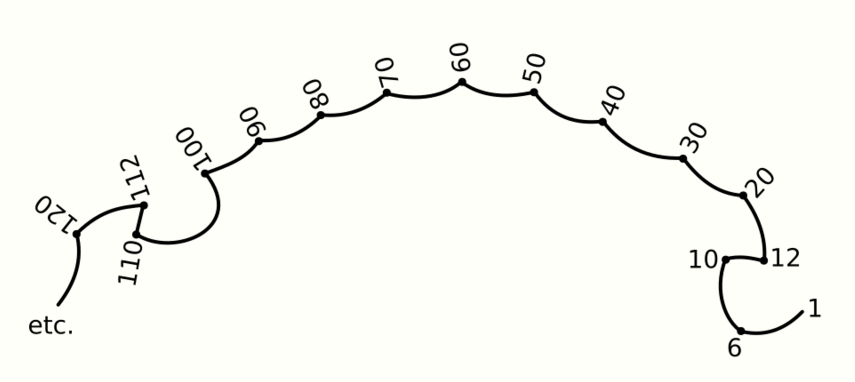

Those with spatial sequence synesthesia (SSS) tend to see ordinal sequences as points in space. People with SSS may have superior memories; in one study, they were able to recall past events and memories far better and in far greater detail than those without the condition. They can also see months or dates in the space around them, but most synesthetes "see" these sequences in their mind's eye. Some people see time like a clock above and around them.[5][6][7]

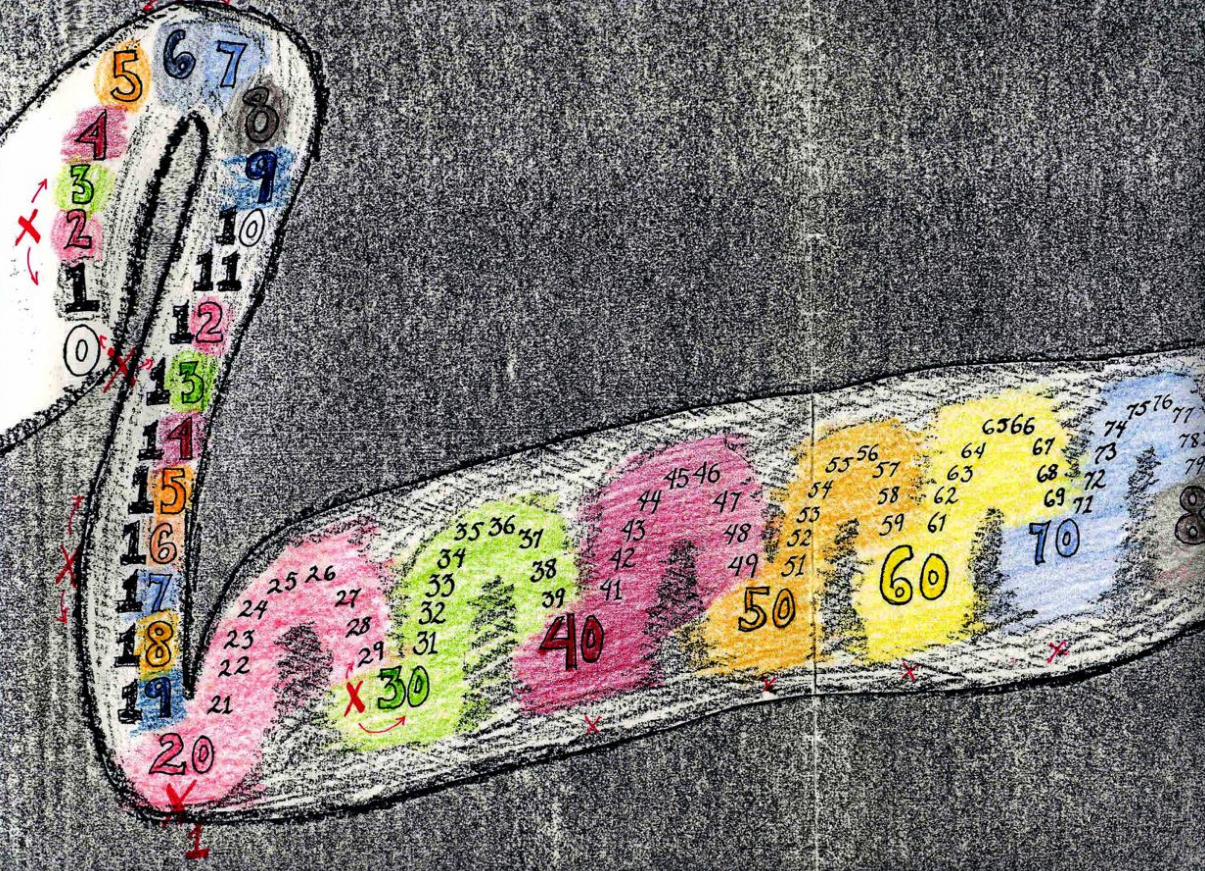

1.4. Number Form

A number form is a mental map of numbers that automatically and involuntarily appear whenever someone who experiences number-forms synesthesia thinks of numbers. These numbers might appear in different locations and the mapping changes and varies between individuals. Number forms were first documented and named in 1881 by Francis Galton in "The Visions of Sane Persons".[9]

1.5. Auditory–Tactile Synesthesia

In auditory–tactile synesthesia, certain sounds can induce sensations in parts of the body. For example, someone with auditory–tactile synesthesia may experience that hearing a specific word or sound feels like touch in one specific part of the body or may experience that certain sounds can create a sensation in the skin without being touched (not to be confused with the milder general reaction known as frisson, which affects approximately 50% of the population). It is one of the least common forms of synesthesia.[10]

1.6. Ordinal Linguistic Personification

Ordinal-linguistic personification (OLP, or personification) is a form of synesthesia in which ordered sequences, such as ordinal numbers, week-day names, months, and alphabetical letters are associated with personalities or genders (Simner & Hubbard 2006). Although this form of synesthesia was documented as early as the 1890s,[11][12] researchers have, until recently, paid little attention to it (see History of synesthesia research). This form of synesthesia was named "OLP" in the contemporary literature by Julia Simner and colleagues[13] although it is now also widely recognised by the term "sequence-personality" synesthesia. Ordinal linguistic personification normally co-occurs with other forms of synesthesia such as grapheme–color synesthesia.

1.7. Misophonia

Misophonia is a neurological disorder in which negative experiences (anger, fright, hatred, disgust) are triggered by specific sounds. Cytowic suggests that misophonia is related to, or perhaps a variety of, synesthesia.[14] Edelstein and her colleagues have compared misophonia to synesthesia in terms of connectivity between different brain regions as well as specific symptoms.[14] They formed the hypothesis that "a pathological distortion of connections between the auditory cortex and limbic structures could cause a form of sound-emotion synesthesia."[15] Studies suggest that individuals with misophonia have a normal hearing sensitivity level but the limbic system and autonomic nervous system are constantly in a "heightened state of arousal" where abnormal reactions to sounds will be more prevalent.[16]

Newer studies suggest that depending on its severity, misophonia could be associated with lower cognitive control when individuals are exposed to certain associations and triggers.[17]

It is unclear what causes misophonia. Some scientists believe it could be genetic, others believe it to be present with other additional conditions however there is not enough evidence to conclude what causes it.[18] There are no current treatments for the condition but could be managed with different types of coping strategies.[18] These strategies vary from person to person, some have reported the avoidance of certain situations that could trigger the reaction: mimicking the sounds, cancelling out the sounds by using different methods like earplugs, music, internal dialog and many other tactics. Most misophonics use these to "overwrite" these sounds produced by others.[19]

1.8. Mirror-Touch Synesthesia

This is a form of synesthesia where individuals feel the same sensation that another person feels (such as touch). For instance, when such a synesthete observes someone being tapped on their shoulder, the synesthete involuntarily feels a tap on their own shoulder as well. People with this type of synesthesia have been shown to have higher empathy levels compared to the general population. This may be related to the so-called mirror neurons present in the motor areas of the brain, which have also been linked to empathy.[20]

1.9. Lexical–Gustatory Synesthesia

This is another form of synesthesia where certain tastes are experienced when hearing words. For example, the word basketball might taste like waffles. The documentary 'Derek Tastes of Earwax' gets its name from this phenomenon, in references to pub owner James Wannerton who experiences this particular sensation whenever he hears the name spoken.[21][22] It is estimated that 0.2% of the synesthesia population has this form of synesthesia, making it the rarest form.[23]

1.10. Kinesthetic Synesthesia

Kinesthetic synesthesia is one of the rarest documented forms of synesthesia in the world.[24] This form of synesthesia is a combination of various different types of synesthesia. Features appear similar to auditory–tactile synesthesia but sensations are not isolated to individual numbers or letters but complex systems of relationships. The result is the ability to memorize and model complex relationships between numerous variables by feeling physical sensations around the kinesthetic movement of related variables. Reports include feeling sensations in the hands or feet, coupled with visualizations of shapes or objects when analyzing mathematical equations, physical systems, or music. In another case, a person described seeing interactions between physical shapes causing sensations in the feet when solving a math problem. Generally, those with this type of synesthesia can memorize and visualize complicated systems, and with a high degree of accuracy, predict the results of changes to the system. Examples include predicting the results of computer simulations in subjects such as quantum mechanics or fluid dynamics when results are not naturally intuitive.[3][25]

1.11. Other Forms

Other forms of synesthesia have been reported, but little has been done to analyze them scientifically. There are at least 80 types of synesthesia.[24]

In August 2017 a research article in the journal Social Neuroscience reviewed studies with fMRI to determine if persons who experience autonomous sensory meridian response are experiencing a form of synesthesia. While a determination has not yet been made, there is anecdotal evidence that this may be the case, based on significant and consistent differences from the control group, in terms of functional connectivity within neural pathways. It is unclear whether this will lead to ASMR being included as a form of existing synesthesia, or if a new type will be considered.[26]

2. Signs and Symptoms

Some synesthetes often report that they were unaware their experiences were unusual until they realized other people did not have them, while others report feeling as if they had been keeping a secret their entire lives.[27] The automatic and ineffable nature of a synesthetic experience means that the pairing may not seem out of the ordinary. This involuntary and consistent nature helps define synesthesia as a real experience. Most synesthetes report that their experiences are pleasant or neutral, although, in rare cases, synesthetes report that their experiences can lead to a degree of sensory overload.[3]

Though often stereotyped in the popular media as a medical condition or neurological aberration, many synesthetes themselves do not perceive their synesthetic experiences as a handicap. On the contrary, some report it as a gift – an additional "hidden" sense – something they would not want to miss. Most synesthetes become aware of their distinctive mode of perception in their childhood. Some have learned how to apply their ability in daily life and work. Synesthetes have used their abilities in memorization of names and telephone numbers, mental arithmetic, and more complex creative activities like producing visual art, music, and theater.[27]

Despite the commonalities which permit the definition of the broad phenomenon of synesthesia, individual experiences vary in numerous ways. This variability was first noticed early in synesthesia research.[28] Some synesthetes report that vowels are more strongly colored, while for others consonants are more strongly colored.[3] Self-reports, interviews, and autobiographical notes by synesthetes demonstrate a great degree of variety in types of synesthesia, the intensity of synesthetic perceptions, awareness of the perceptual discrepancies between synesthetes and non-synesthetes, and the ways synesthesia is used in work, creative processes, and daily life.[27][29]

Synesthetes are very likely to participate in creative activities.[25] It has been suggested that individual development of perceptual and cognitive skills, in addition to one's cultural environment, produces the variety in awareness and practical use of synesthetic phenomena.[29][30] Synesthesia may also give a memory advantage. In one study, conducted by Julia Simner of the University of Edinburgh, it was found that spatial sequence synesthetes have a built-in and automatic mnemonic reference. Whereas a non-synesthete will need to create a mnemonic device to remember a sequence (like dates in a diary), a synesthete can simply reference their spatial visualizations.[31]

3. Mechanism

As of 2015, the neurological correlates of synesthesia had not been established.[33]

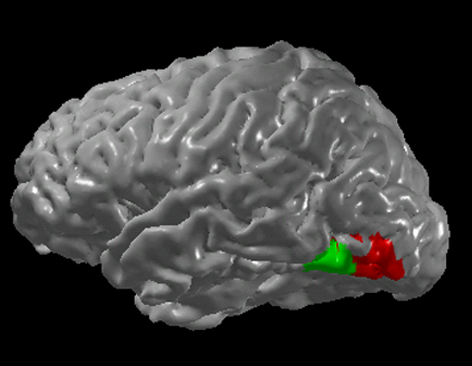

Dedicated regions of the brain are specialized for given functions. Increased cross-talk between regions specialized for different functions may account for the many types of synesthesia. For example, the additive experience of seeing color when looking at graphemes might be due to cross-activation of the grapheme-recognition area and the color area called V4 (see figure).[32] This is supported by the fact that grapheme–color synesthetes can identify the color of a grapheme in their peripheral vision even when they cannot consciously identify the shape of the grapheme.[32]

An alternative possibility is disinhibited feedback, or a reduction in the amount of inhibition along normally existing feedback pathways.[34] Normally, excitation and inhibition are balanced. However, if normal feedback were not inhibited as usual, then signals feeding back from late stages of multi-sensory processing might influence earlier stages such that tones could activate vision. Cytowic and Eagleman find support for the disinhibition idea in the so-called acquired forms[2] of synesthesia that occur in non-synesthetes under certain conditions: temporal lobe epilepsy,[35] head trauma, stroke, and brain tumors. They also note that it can likewise occur during stages of meditation, deep concentration, sensory deprivation, or with use of psychedelics such as LSD or mescaline, and even, in some cases, marijuana.[2] However, synesthetes report that common stimulants, like caffeine and cigarettes do not affect the strength of their synesthesia, nor does alcohol.[2]:137–40

A very different theoretical approach to synesthesia is that based on ideasthesia. According to this account, synesthesia is a phenomenon mediated by the extraction of the meaning of the inducing stimulus. Thus, synesthesia may be fundamentally a semantic phenomenon. Therefore, to understand neural mechanisms of synesthesia the mechanisms of semantics and the extraction of meaning need to be understood better. This is a non-trivial issue because it is not only a question of a location in the brain at which meaning is "processed" but pertains also to the question of understanding – epitomized in e.g., the Chinese room problem. Thus, the question of the neural basis of synesthesia is deeply entrenched into the general mind–body problem and the problem of the explanatory gap.[36]

3.1. Genetics

Due to the prevalence of synesthesia among the first-degree relatives of people affected,[37] there may be a genetic basis, as indicated by the monozygotic twins studies showing an epigenetic component. Synesthesia might also be an oligogenic condition, with locus heterogeneity, multiple forms of inheritance, and continuous variation in gene expression. While the exact genetic loci for this trait haven't been identified, research indicates that the genetic constructs underlying synesthesia are most likely more complex than the simple X-linked mode of inheritance that early researchers believed it to be.[38] Further, it remains uncertain as to whether synesthesia perseveres in the genetic pool because it provides a selective advantage, or because it has become a byproduct of some other useful selected trait.[39] Women have a higher chance of developing synesthesia, as demonstrated in the UK where females are 8 times more likely to have it. As technological equipment continues to advance, the search for clearer answers regarding the genetics behind synesthesia will become more promising.

Although often termed a "neurological condition," synesthesia is not listed in either the DSM-IV or the ICD since it usually does not interfere with normal daily functioning.[40] Indeed, most synesthetes report that their experiences are neutral or even pleasant.[3] Like perfect pitch, synesthesia is simply a difference in perceptual experience.

The simplest approach is test-retest reliability over long periods of time, using stimuli of color names, color chips, or a computer-screen color picker providing 16.7 million choices. Synesthetes consistently score around 90% on the reliability of associations, even with years between tests.[14] In contrast, non-synesthetes score just 30–40%, even with only a few weeks between tests and a warning that they would be retested.[14]

Many tests exist for synesthesia. Each common type has a specific test. When testing for grapheme–color synesthesia, a visual test is given. The person is shown a picture that includes black letters and numbers. A synesthete will associate the letters and numbers with a specific color. An auditory test is another way to test for synesthesia. A sound is turned on and one will either identify it with a taste or envision shapes. The audio test correlates with chromesthesia (sounds with colors). Since people question whether or not synesthesia is tied to memory, the "retest" is given. One is given a set of objects and is asked to assign colors, tastes, personalities, or more. After a period of time, the same objects are presented and the person is asked again to do the same task. The synesthete can assign the same characteristics because that person has permanent neural associations in the brain, rather than memories of a certain object.

Grapheme–color synesthetes, as a group, share significant preferences for the color of each letter (e.g., A tends to be red; O tends to be white or black; S tends to be yellow, etc.)[3] Nonetheless, there is a great variety in types of synesthesia, and within each type, individuals report differing triggers for their sensations and differing intensities of experiences. This variety means that defining synesthesia in an individual is difficult, and the majority of synesthetes are completely unaware that their experiences have a name.[3]

Neurologist Richard Cytowic identifies the following diagnostic criteria for synesthesia in his first edition book. However, the criteria are different in the second book:[2][14][41]

- Synesthesia is involuntary and automatic.

- Synesthetic perceptions are spatially extended, meaning they often have a sense of "location." For example, synesthetes speak of "looking at" or "going to" a particular place to attend to the experience.

- Synesthetic percepts are consistent and generic (i.e., simple rather than pictorial).

- Synesthesia is highly memorable.

- Synesthesia is laden with affect.

Cytowic's early cases mainly included individuals whose synesthesia was frankly projected outside the body (e.g., on a "screen" in front of one's face). Later research showed that such stark externalization occurs in a minority of synesthetes. Refining this concept, Cytowic and Eagleman differentiated between "localizers" and "non-localizers" to distinguish those synesthetes whose perceptions have a definite sense of spatial quality from those whose perceptions do not.[2]

4. Prevalence

Estimates of prevalence of synesthesia have ranged widely, from 1 in 4 to 1 in 25,000–100,000. However, most studies have relied on synesthetes reporting themselves, introducing self-referral bias.[42] In what is cited as the most accurate prevalence study so far,[42] self-referral bias was avoided by studying 500 people recruited from the communities of Edinburgh and Glasgow Universities; it showed a prevalence of 4.4%, with 9 different variations of synesthesia.[43] This study also concluded that one common form of synesthesia – grapheme–color synesthesia (colored letters and numbers) – is found in more than one percent of the population, and this latter prevalence of graphemes–color synesthesia has since been independently verified in a sample of nearly 3,000 people in the University of Edinburgh.[44]

The most common forms of synesthesia are those that trigger colors, and the most prevalent of all is day–color.[43] Also relatively common is grapheme–color synesthesia. We can think of "prevalence" both in terms of how common is synesthesia (or different forms of synesthesia) within the population, or how common are different forms of synesthesia within synesthetes. So within synesthetes, forms of synesthesia that trigger color also appear to be the most common forms of synesthesia with a prevalence rate of 86% within synesthetes.[43] In another study, music–color is also prevalent at 18–41%. Some of the rarest are reported to be auditory–tactile, mirror-touch, and lexical–gustatory.[45]

There is research to suggest that the likelihood of having synesthesia is greater in people with autism spectrum condition.[46]

5. History

The interest in colored hearing dates back to Greek antiquity when philosophers asked if the color (chroia, what we now call timbre) of music was a quantifiable quality.[47] Isaac Newton proposed that musical tones and color tones shared common frequencies, as did Goethe in his book Theory of Colours.[48] There is a long history of building color organs such as the clavier à lumières on which to perform colored music in concert halls.[49][50]

The first medical description of "colored hearing" is in an 1812 thesis by the German physician Georg Tobias Ludwig Sachs.[51][52][53] The "father of psychophysics," Gustav Fechner, reported the first empirical survey of colored letter photisms among 73 synesthetes in 1876,[54][55] followed in the 1880s by Francis Galton.[8][56][57] Carl Jung refers to "color hearing" in his Symbols of Transformation in 1912.[58]

In the early 1920s, the Bauhaus teacher and musician Gertrud Grunow researched the relationships between sound, color, and movement and developed a 'twelve-tone circle of colour' which was analogous with the twelve-tone music of the Austrian composer Arnold Schönberg (1874-1951).[59] She was a participant in at least one of the Congresses for Colour-Sound Research (German:Kongreß für Farbe-Ton-Forschung) held in Hamburg in the late 1920s and early 1930s.[60]

Research into synesthesia proceeded briskly in several countries, but due to the difficulties in measuring subjective experiences and the rise of behaviorism, which made the study of any subjective experience taboo, synesthesia faded into scientific oblivion between 1930 and 1980.

As the 1980s cognitive revolution made inquiry into internal subjective states respectable again, scientists returned to synesthesia. Led in the United States by Larry Marks and Richard Cytowic, and later in England by Simon Baron-Cohen and Jeffrey Gray, researchers explored the reality, consistency, and frequency of synesthetic experiences. In the late 1990s, the focus settled on grapheme → color synesthesia, one of the most common[3] and easily studied types. Psychologists and neuroscientists study synesthesia not only for its inherent appeal but also for the insights it may give into cognitive and perceptual processes that occur in synesthetes and non-synesthetes alike. Synesthesia is now the topic of scientific books and papers, Ph.D. theses, documentary films, and even novels.

Since the rise of the Internet in the 1990s, synesthetesia began contacting one another and creating websites devoted to the condition. These rapidly grew into international organizations such as the American Synesthesia Association, the UK Synaesthesia Association, the Belgian Synesthesia Association, the Canadian Synesthesia Association, the German Synesthesia Association, and the Netherlands Synesthesia Web Community.

6. Society and Culture

6.1. Notable Cases

Solomon Shereshevsky, a newspaper reporter turned celebrated mnemonist, was discovered by Russian neuropsychologist Alexander Luria to have a rare fivefold form of synesthesia, of which he is the only known case.[1] Words and text were not only associated with highly vivid visuospatial imagery but also sound, taste, color, and sensation.[1] Shereshevsky could recount endless details of many things without form, from lists of names to decades-old conversations, but he had great difficulty grasping abstract concepts. The automatic, and nearly permanent, retention of every detail due to synesthesia greatly inhibited Shereshevsky's ability to understand what he read or heard.[1]

Neuroscientist and author V.S. Ramachandran studied the case of a grapheme–color synesthete who was also color blind. While he couldn't see certain colors with his eyes, he could still "see" those colors when looking at certain letters. Because he didn't have a name for those colors, he called them "Martian colors."[61]

6.2. Art

Other notable synesthetes come particularly from artistic professions and backgrounds. Synesthetic art historically refers to multi-sensory experiments in the genres of visual music, music visualization, audiovisual art, abstract film, and intermedia.[27][62][63][64][65][66] Distinct from neuroscience, the concept of synesthesia in the arts is regarded as the simultaneous perception of multiple stimuli in one gestalt experience.[67] Neurological synesthesia has been a source of inspiration for artists, composers, poets, novelists, and digital artists.

Writers

Vladimir Nabokov writes explicitly about synesthesia in several novels. Nabokov described his grapheme–color synesthesia at length in his autobiography, Speak, Memory, and portrayed it in some of his characters.[68] In addition to Messiaen, whose three types of complex colors are rendered explicitly in musical chord structures that he invented,[2][69] other composers who reported synesthesia include Duke Ellington,[70] Rimsky-Korsakov,[71] and Jean Sibelius.[63] Daniel Tammet wrote a book on his experiences with synesthesia called Born on a Blue Day.[72] Joanne Harris, author of Chocolat, is a synesthete who says she experiences colors as scents.[73] Her novel Blueeyedboy features various aspects of synesthesia.

Painters and photographers

Wassily Kandinsky (a synesthete) and Piet Mondrian (not a synesthete) both experimented with image–music congruence in their paintings. Contemporary artists with synesthesia, such as Carol Steen[74] and Marcia Smilack[75] (a photographer who waits until she gets a synesthetic response from what she sees and then takes the picture), use their synesthesia to create their artwork. Linda Anderson, according to NPR considered "one of the foremost living memory painters", creates with oil crayons on fine-grain sandpaper representations of the auditory-visual synaesthesia she experiences during severe migraine attacks.[76][77] Brandy Gale, a Canadian visual artist, experiences an involuntary joining or crossing of any of her senses – hearing, vision, taste, touch, smell and movement. Gale paints from life rather than from photographs and by exploring the sensory panorama of each locale attempts to capture, select, and transmit these personal experiences.[78][79][80] David Hockney perceives music as color, shape, and configuration and uses these perceptions when painting opera stage sets (though not while creating his other artworks). Kandinsky combined four senses: color, hearing, touch, and smell.[2][14]

Composers

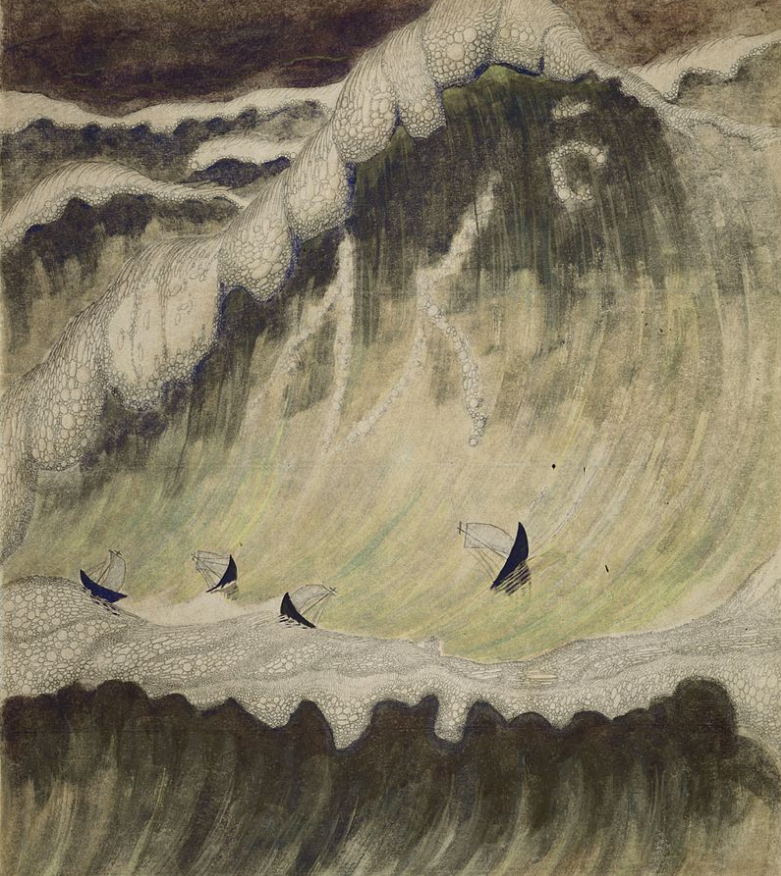

Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis, 1875 – 1911, was a Lithuanian painter, composer and writer. In his short life, he composed about 400 pieces of music and created about 300 paintings, as well as many literary works and poems. He perceived colors and music simultaneously. Many of his paintings bear the names of matching musical pieces: sonatas, fugues, and preludes. Čiurlionis's works have been displayed at international exhibitions in Japan, Germany, Spain, and elsewhere. His paintings were featured at "Visual Music" fest, an homage to synesthesia that included the works of Wassily Kandinsky, James McNeill Whistler, and Paul Klee, at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles in 2005. Čiurlionis's life was depicted in the 2012 film Letters to Sofija, directed by Robert Mullan. Example matching image and music on the right:

Alexander Scriabin composed colored music that was deliberately contrived and based on the circle of fifths, whereas Olivier Messiaen invented a new method of composition (the modes of limited transposition) specifically to render his bi-directional sound–color synesthesia. For example, the red rocks of Bryce Canyon are depicted in his symphony Des canyons aux étoiles... ("From the Canyons to the Stars"). New art movements such as literary symbolism, non-figurative art, and visual music have profited from experiments with synesthetic perception and contributed to the public awareness of synesthetic and multi-sensory ways of perceiving.[27] Michael Torke is a contemporary example of a synesthetic composer.[63] Ramin Djawadi, a composer best known for his work on composing the theme songs and scores for such TV series as Game of Thrones, Westworld and for the Iron Man movie, also has synesthesia. He says he tends to "associate colors with music, or music with colors."[81]

British composer Daniel Liam Glyn created the classical-contemporary music project Changing Stations using Grapheme Colour Synaesthesia. Based on the 11 main lines of the London Underground, the eleven tracks featured on the album represent the eleven main tube line colours: Bakerloo, Central, Circle, District, Hammersmith and City, Jubilee, Metropolitan, Northern, Piccadilly, Victoria, and Waterloo and City.[82] Each track focuses heavily on the different speeds, sounds, and mood of each line, and are composed in the key signature synaesthetically assigned by Glyn with reference to the colour of the tube line on the map.[83]

Musicians

The producer, rapper, and fashion designer Kanye West is a prominent interdisciplinary case. In an impromptu speech he gave during an Ellen interview, he described his condition, saying that he sees sounds, and that everything he sonically makes is a painting.[84] Other notable synesthetes include musicians Billy Joel,[85]:89, 91 Andy Partridge,[86] Itzhak Perlman,[85]:53 Lorde,[87] Billie Eilish,[88] Brendon Urie,[89][90] Ida Maria,[91] and Brian Chase;[92][93] electronic musician Richard D. James a.k.a. Aphex Twin (who claims to be inspired by lucid dreams as well as music); and classical pianist Hélène Grimaud. Musician Kristin Hersh sees music in colors.[94] Drummer Mickey Hart of The Grateful Dead wrote about his experiences with synaesthesia in his autobiography Drumming at the Edge of Magic.[95] Pharrell Williams, of the groups The Neptunes and N.E.R.D., also experiences synesthesia[96][97] and used it as the basis of the album Seeing Sounds. Singer/songwriter Marina and the Diamonds experiences music → color synesthesia and reports colored days of the week.[98]

Artists without synesthesia

Some artists frequently mentioned as synesthetes did not, in fact, have the neurological condition. Scriabin's 1911 Prometheus, for example, is a deliberate contrivance whose color choices are based on the circle of fifths and appear to have been taken from Madame Blavatsky.[2][99] The musical score has a separate staff marked luce whose "notes" are played on a color organ. Technical reviews appear in period volumes of Scientific American.[2] On the other hand, his older colleague Rimsky-Korsakov (who was perceived as a fairly conservative composer) was, in fact, a synesthete.[100]

French poets Arthur Rimbaud and Charles Baudelaire wrote of synesthetic experiences, but there is no evidence they were synesthetes themselves. Baudelaire's 1857 Correspondances introduced the notion that the senses can and should intermingle. Baudelaire participated in a hashish experiment by psychiatrist Jacques-Joseph Moreau and became interested in how the senses might affect each other.[27] Rimbaud later wrote Voyelles (1871), which was perhaps more important than Correspondances in popularizing synesthesia. He later boasted "J'inventais la couleur des voyelles!" (I invented the colors of the vowels!).[101]

6.3. Science

Some technologists, like inventor Nikola Tesla,[102] and scientists also reported being synesthetic. Physicist Richard Feynman describes his colored equations in his autobiography, What Do You Care What Other People Think?.[103]

6.4. Literature

Synesthesia is sometimes used as a plot device or way of developing a character's inner life. Author and synesthete Pat Duffy describes four ways in which synesthetic characters have been used in modern fiction.[104][105]

- Synesthesia as Romantic ideal: in which the condition illustrates the Romantic ideal of transcending one's experience of the world. Books in this category include The Gift by Vladimir Nabokov.

- Synesthesia as pathology: in which the trait is pathological. Books in this category include The Whole World Over by Julia Glass.

- Synesthesia as Romantic pathology: in which synesthesia is pathological but also provides an avenue to the Romantic ideal of transcending quotidian experience. Books in this category include Holly Payne's The Sound of Blue and Anna Ferrara's The Woman Who Tried To Be Normal.

- Synesthesia as psychological health and balance: Painting Ruby Tuesday by Jane Yardley, and A Mango-Shaped Space by Wendy Mass.

Literary depictions of synesthesia are criticized as often being more of a reflection of an author's interpretation of synesthesia than of the phenomenon itself.

7. Research

Research on synesthesia raises questions about how the brain combines information from different sensory modalities, referred to as crossmodal perception or multisensory integration.

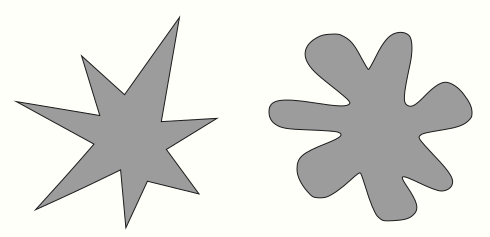

An example of this is the bouba/kiki effect. In an experiment first designed by Wolfgang Köhler, people are asked to choose which of two shapes is named bouba and which kiki. The angular shape, kiki, is chosen by 95–98% and bouba for the rounded one. Individuals on the island of Tenerife showed a similar preference between shapes called takete and maluma. Even 2.5-year-old children (too young to read) show this effect.[106] Research indicated that in the background of this effect may operate a form of ideasthesia.[107]

Researchers hope that the study of synesthesia will provide better understanding of consciousness and its neural correlates. In particular, synesthesia might be relevant to the philosophical problem of qualia,[108][109] given that synesthetes experience extra qualia (e.g., colored sound). An important insight for qualia research may come from the findings that synesthesia has the properties of ideasthesia,[110] which then suggest a crucial role of conceptualization processes in generating qualia.[111]

7.1. Technological Applications

Synesthesia also has a number of practical applications, one of which is the use of 'intentional synesthesia' in technology.[112] These applications include sensory prosthetics, as discussed by Chaim-Meyer Scheff in "Experimental model for the study of changes in the organization of human sensory information processing through the design and testing of non-invasive prosthetic devices for sensory impaired people".[SIGCAPH Comput. Phys. Handicap. (36): 3–10. doi:10.1145/15711.15713. S2CID 119242 [113]]

The Voice (vOICe)

Peter Meijer developed a sensory substitution device for the visually impaired called The vOICe (the capital letters "O," "I," and "C" in "vOICe" are intended to evoke the expression "Oh I see"). The vOICe is a privately owned research project, running without venture capital, that was first implemented using low-cost hardware in 1991.[114] The vOICe is a visual-to-auditory sensory substitution device (SSD) preserving visual detail at high resolution (up to 25,344 pixels).[115] The device consists of a laptop, head-mounted camera or computer camera, and headphones. The vOICe converts visual stimuli of the surroundings captured by the camera into corresponding aural representations (soundscapes) delivered to the user through headphones at a default rate of one soundscape per second. Each soundscape is a left-to-right scan, with height represented by pitch, and brightness by loudness.[116] The vOICe compensates for the loss of vision by converting information from the lost sensory modality into stimuli in a remaining modality.[117]

References

- Searching for Memory: The Brain, The Mind, And The Past. Basic Books. 1996. pp. 81. ISBN 978-0-465-07552-2. https://archive.org/details/searchingformemo00dani/page/81.

- Wednesday is Indigo Blue: Discovering the Brain of Synesthesia (with an afterword by Dmitri Nabokov). Cambridge: MIT Press. 2009. ISBN 978-0-262-01279-9.

- Synesthesia: perspectives from cognitive neuroscience. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2005. ISBN 978-0-19-516623-1. OCLC 53020292. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/53020292

- "Absolute Pitch and Synesthesia | The Feinstein Institute for Medical Research" (in en-US). http://www.feinsteininstitute.org/robert-s-boas-center-for-genomics-and-human-genetics/projects/genetics-and-epidemiology-of-absolute-pitch-and-related-cognitive-traits/.

- Jonas, Clare N.; Price, Mark C. (2014-10-30). "Not all synesthetes are alike: spatial vs. visual dimensions of sequence-space synesthesia". Frontiers in Psychology 5: 1171. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01171. ISSN 1664-1078. PMID 25400596. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=4214186

- Do sequence-space synaesthetes have better spatial imagery skills? Maybe not, The National Center for Biotechnology Information http://www.sciencemag.org/site/help/about/index.xhtml

- A Mind That Touches the Past, Sciencemag.org https://www.science.org/content/article/mind-touches-past

- "Visualized Numerals". Nature 21 (543): 494–5. 1880. doi:10.1038/021494e0. Bibcode: 1880Natur..21..494G. https://zenodo.org/record/1429243.

- "The Visions of Sane Persons". Ploughshares 39 (1): 144–145. 2013. doi:10.1353/plo.2013.0012. ISSN 2162-0903. https://dx.doi.org/10.1353%2Fplo.2013.0012

- "Touching sounds: thalamocortical plasticity and the neural basis of multisensory integration". Journal of Neurophysiology 102 (1): 7–8. July 2009. doi:10.1152/jn.00209.2009. PMID 19403745. http://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/28e0/779e6d740192099466d629c490f93210eff5.pdf.

- Flournoy 2001

- Calkins 1893

- "Variants of synesthesia interact in cognitive tasks: evidence for implicit associations and late connectivity in cross-talk theories". Neuroscience 143 (3): 805–814. December 2006. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.08.018. PMID 16996695. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.neuroscience.2006.08.018

- Synesthesia: A Union of the Senses (2nd ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. 2002. ISBN 978-0-262-03296-4. OCLC 49395033. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/49395033

- "Misophonia: physiological investigations and case descriptions". Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 7: 296. 2013. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2013.00296. PMID 23805089. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3691507

- "Diminished n1 auditory evoked potentials to oddball stimuli in misophonia patients". Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience 8: 123. 2014-04-09. doi:10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00123. PMID 24782731. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3988356

- "Severity of misophonia symptoms is associated with worse cognitive control when exposed to misophonia trigger sounds". PLOS ONE 15 (1): e0227118. 2020-01-16. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0227118. PMID 31945068. Bibcode: 2020PLoSO..1527118D. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=6964854

- "Misophonia: An Overview" (in en). Seminars in Hearing 35 (2): 084–091. 2014-04-29. doi:10.1055/s-0034-1372525. ISSN 0734-0451. https://dx.doi.org/10.1055%2Fs-0034-1372525

- "Misophonia: physiological investigations and case descriptions". Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 7: 296. 2013. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2013.00296. PMID 23805089. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3691507

- "Where do mirror neurons come from?". Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 34 (4): 575–583. March 2010. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.11.007. PMID 19914284. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.neubiorev.2009.11.007

- "Derek Tastes of Ear Wax". Top Documentary Films. http://topdocumentaryfilms.com/derek-tastes-of-ear-wax.

- "BBC – Science & Nature – Horizon". bbc.co.uk. http://www.bbc.co.uk/sn/tvradio/programmes/horizon/derek_prog_summary.shtml.

- "Lexical–Gustatory Synesthesia". Encyclopedia of Neuroscience. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. 2009. pp. 2149–2152. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-29678-2_2766. ISBN 978-3-540-23735-8. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2F978-3-540-29678-2_2766

- "Types-of-Syn". http://www.daysyn.com/Types-of-Syn.html.

- "Creativity, synesthesia, and physiognomic perception". Creativity Research Journal 10 (1): 1–8. 1997. doi:10.1207/s15326934crj1001_1. https://dx.doi.org/10.1207%2Fs15326934crj1001_1

- "An examination of the default mode network in individuals with autonomous sensory meridian response (ASMR)". Social Neuroscience 12 (4): 361–365. August 2017. doi:10.1080/17470919.2016.1188851. PMID 27196787. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080%2F17470919.2016.1188851

- The Hidden Sense: Synesthesia in Art and Science. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. 2007. ISBN 978-0-262-22081-1. OCLC 80179991. https://archive.org/details/hiddensensesynes0000camp.

- Des phénomènes de synopsie (Audition colorée). Adamant Media Corporation. 2001. ISBN 978-0-543-94462-7.

- (in German) Synästhesien. Roter Faden durchs Leben?. Essen: Verlag Die Blaue Eule. 2007.

- "The Hidden Sense: On Becoming Aware of Synesthesia". Teccogs 1: 1–13. 2009. http://www.pucsp.br/pos/tidd/teccogs/artigos/pdf/teccogs_edicao1_2009_artigo_CAMPEN.pdf.

- "Investigating Spatial Sequence Synesthesia" (in en-US). 2012-06-26. http://www.synesthesiatest.org/blog/spatial-sequence-synesthesia#sthash.gan4VYDZ.dpuf.

- "Synaesthesia: A window into perception, thought and language". Journal of Consciousness Studies 8 (12): 3–34. 2001. http://psy.ucsd.edu/~edhubbard/papers/JCS.pdf.

- "A critical review of the neuroimaging literature on synesthesia". Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 9: 103. 2015. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2015.00103. PMID 25873873. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=4379872

- "Mechanisms of synesthesia: cognitive and physiological constraints". Trends in Cognitive Sciences 5 (1): 36–41. January 2001. doi:10.1016/S1364-6613(00)01571-0. PMID 11164734. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2FS1364-6613%2800%2901571-0

- "Synesthetic associations and psychosensory symptoms of temporal epilepsy". Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment 12: 109–112. 11 January 2016. doi:10.2147/NDT.S95464. PMID 26811683. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=4714732

- "Evidence against functionalism from neuroimaging of the alien colour effect in synaesthesia". Cortex; A Journal Devoted to the Study of the Nervous System and Behavior 42 (2): 309–318. February 2006. doi:10.1016/s0010-9452(08)70357-5. PMID 16683506. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fs0010-9452%2808%2970357-5

- "Synaesthesia: prevalence and familiality". Perception 25 (9): 1073–1079. 1 September 1996. doi:10.1068/p251073. PMID 8983047. https://dx.doi.org/10.1068%2Fp251073

- "Neurocognitive mechanisms of synesthesia". Neuron 48 (3): 509–520. November 2005. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2005.10.012. PMID 16269367. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.neuron.2005.10.012

- "Survival of the synesthesia gene: why do people hear colors and taste words?". PLOS Biology 9 (11): e1001205. November 2011. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001205. PMID 22131906. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3222625

- "Neurophysiology of synesthesia". Current Psychiatry Reports 9 (3): 193–199. June 2007. doi:10.1007/s11920-007-0018-6. PMID 17521514. https://www.hal.inserm.fr/inserm-00150599/file/Hubbard_CurrPsychReports.pdf.

- The Man Who Tasted Shapes. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. 2003. ISBN 978-0-262-53255-6. OCLC 53186027. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/53186027

- "A brief history of synesthesia research" (in en). Oxford Handbook of Synesthesia. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. 2013. pp. 13–17. ISBN 978-0-19-960332-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=WXq9AgAAQBAJ&q=Oxford+Handbook+of+Synesthesia. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- "Synaesthesia: the prevalence of atypical cross-modal experiences". Perception 35 (8): 1024–1033. 2006. doi:10.1068/p5469. PMID 17076063. http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/14073/1/p5469.pdf.

- "Validating a standardised test battery for synesthesia: Does the Synesthesia Battery reliably detect synesthesia?". Consciousness and Cognition 33: 375–385. May 2015. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2015.02.001. PMID 25734257. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=5047354

- "Color synesthesia. Insight into perception, emotion, and consciousness". Current Opinion in Neurology 28 (1): 36–44. February 2015. doi:10.1097/WCO.0000000000000169. PMID 25545055. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=4286234

- Baron-Cohen S, Johnson D, Asher J, Wheelwright S, Fisher SE, Gregerson PK, Allison C, "Is synaesthesia more common in autism?", Molecular Autism, 20 November 2013

- Colour and Culture. Practice and Meaning from Antiquity to Abstraction. London: Thames & Hudson. 1993.

- Theory of Colours. J. Murray. 1840.

- "Instruments to Perform Color-Music: Two Centuries of Technological Experimentation". Leonardo 21 (4): 397–406. 1988. doi:10.2307/1578702. http://www.matchtoneapp.com/images/instrumentstoperformcolor.pdf.

- Farbe – Licht – Musik. Synaesthesie und Farblichtmusik.. Bern: Peter Lang. 2006.

- "Das Problem der 'audition colorée': Eine historisch-kritische Untersuchung". Archiv für die gesamte Psychologie 57: 165–301. 1926.

- "A colorful albino: the first documented case of synaesthesia, by Georg Tobias Ludwig Sachs in 1812". Journal of the History of the Neurosciences 18 (3): 293–303. July 2009. doi:10.1080/09647040802431946. PMID 20183209. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080%2F09647040802431946

- "Synesthesia". 2018-12-28. https://www.britannica.com/science/synesthesia.

- Vorschule der Aesthetik. Leipzig: Breitkopf und Hartel. 1876. https://archive.org/details/vorschulederaest12fechuoft.

- "De verwarring der zintuigen. Artistieke en psychologische experimenten met synesthesie". Psychologie & Maatschappij 20 (1): 10–26. 1996.

- "Visualized Numerals". Nature 21 (533): 252–6. 1880. doi:10.1038/021252a0. Bibcode: 1880Natur..21..252G. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038%2F021252a0

- Inquiries into Human Faculty and Its Development. Macmillan. 1883. http://galton.org/books/human-faculty/. Retrieved 2008-06-17.

- "The Transformation of Libido". Symbols of Transformation. CW5, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. 1956. p. 237.

- Bauhaus100.Curriculum. Harmonisation theory 1919-1924. Retrieved 2 December 2018 https://www.bauhaus100.com/the-bauhaus/training/curriculum/classes-by-gertrud-grunow/

- Farbe-Ton-Forschungen. III. Band. Bericht über den II. Kongreß für Farbe-Ton-Forschung (Hamburg 1. - 5. Oktober 1930). Published 1931.

- "Martian Colors - Cosmic Variance". 5 November 2007. https://www.discovermagazine.com/the-sciences/martian-colors.

- "Artistic and psychological experiments with synesthesia". Leonardo 32 (1): 9–14. 1999. doi:10.1162/002409499552948. https://dx.doi.org/10.1162%2F002409499552948

- "Synesthesia and the Arts". Leonardo 32 (1): 15–22. 1999. doi:10.1162/002409499552957. https://dx.doi.org/10.1162%2F002409499552957

- The Sound of Painting: Music in Modern Art (Pegasus Library). Munich: Prestel. 1999. ISBN 978-3-7913-2082-3.

- Colour and culture: practice and meaning from antiquity to abstraction. London: Thames and Hudson. 1993. ISBN 978-0-500-27818-5.

- Color and meaning: art, science, and symbolism. Berkeley: University of California Press. 1999. ISBN 978-0-520-22611-1.

- "Visual Music and Musical Paintings. The Quest for Synesthesia in the Arts.". Making Sense of Art, making Art of Sense.. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2009.

- Speak, Memory: An Autobiography Revisited. New York: Putnam. 1966.

- Olivier Messiaen: Music and Color. Conversations with Claude Samuel.. Portland, Oregon: Amadeus Press. 1994.

- Duke Ellington as quoted in Sweet man: The real Duke Ellington.. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons. 1981. p. 226.

- according to the Russian press: "On N.A.Rimsky-Korsakov's color sound- contemplation." (in Russian). Russkaya Muzykalnaya Gazeta (39–40): 842–845. 1908. cited by Bulat Galeyev (1999).

- Born on a Blue Day. Free Press. 2007. ISBN 978-1-4165-3507-2. https://archive.org/details/bornonbluedayins00tamm.

- "Chocolat author Joanne Harris talks about her latest novel Blue Eyed Boy". Metro. 7 April 2010. http://metro.co.uk/2010/04/07/chocolat-author-joanne-harris-talks-about-her-latest-novel-blue-eyed-boy-226133/.

- "Visions Shared: A Firsthand Look into Synesthesia and Art". Leonardo 34 (3): 203–208. 2001. doi:10.1162/002409401750286949. https://dx.doi.org/10.1162%2F002409401750286949

- Marcia Smilack Website Accessed 20 August 2006. http://www.marciasmilack.com/synethesia-intro.php

- "Linda Anderson - MOCA GA". 2019-04-07. https://mocaga.org/collections/permanent-art-collection-artists/linda-anderson/.

- "Linda Anderson". 2019-04-07. http://www.gpb.org/stateofthearts/term/anderson.

- "Coastal Synaesthesia: Paintings and Photographs of Hawaii, Fiji and California by Brandy Gale – Gualala Arts Center exhibit: January, 2015". gualalaarts.org. http://www.gualalaarts.org/Exhibits/Gallery/2015-01-Coastal-Synaesthesia.html.

- EG. "The Wondrous Sensory Spectrum of Brandy Gale". FORA.tv. http://library.fora.tv/2013/04/19/The_Wondrous_Sensory_Spectrum_of_Brandy_Gale.

- brandygale.com http://BrandyGale.com

- "Meet the musical genius behind the 'Game of Thrones' soundtrack who watches each season before anyone else" (in en). Business Insider. http://www.businessinsider.com/game-of-thrones-music-composer-ramin-djawadi-interview-2016-7.

- "Sounds of the Underground: Synaesthetic Musician Creates LP Based on Tube Map". The Big Issue. 27 April 2017. https://www.bigissue.com/news/sounds-underground-synaesthetic-musician-creates-lp-based-tube-map/. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- "Do all London Underground lines have a unique sound?". Norwegian Air Magazine. http://pages.cdn.pagesuite.com/7/8/7848c73a-e3c4-4f48-9fd3-18c7ac451991/page.pdf. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- (in en) Kanye West FULL Banned Ellen Interview HD May 19 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W58_fnZ3oGQ, retrieved 2022-08-20

- Tasting the Universe. New Page Books. 2011. ISBN 978-1-60163-159-6.

- https://tidal.com/magazine/article/inside-synesthesia/1-72048

- "Lorde explains the experience of having synaesthesia". 2017-05-11. https://www.nme.com/news/music/lorde-synaesthesia-explained-2069855.

- "Billie Eilish Explains How Synesthesia Affects Her Music" (in en). https://www.iheart.com/content/2019-05-29-billie-eilish-explains-how-synesthesia-affects-her-music/.

- "Panic! at the Disco: Band Is 'Outlet for Nonchalant Chaos'" (in en-US). Rolling Stone. 2016-01-15. https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-features/panic-at-the-discos-brendon-urie-band-is-outlet-for-nonchalant-chaos-188429/. Retrieved 2019-11-13.

- "4 Singers Who Draw Inspiration From Synesthesia To Write Music" (in en-US). 23 January 2018. https://culturacolectiva.com/music/singers-with-synesthesia-inspiration-sounds.

- "Times Online interview". The Times (London). 24 February 2008. http://entertainment.timesonline.co.uk/tol/arts_and_entertainment/music/article3404605.ece.

- "Emma Forrest meets New York's favourite art-punk rockers Yeah Yeah Yeahs". guardian.co.uk (London: The Guardian). 30 March 2009. https://www.theguardian.com/music/2009/mar/30/pop-music-yeah-yeah-yeahs.

- "Brian Chase's blog". yeahyeahyeahs.com. http://site.yeahyeahyeahs.com/blog/brian.aspx.

- Seaman, Duncan (May 8, 2021). "Strange Angels: Kristin Hersh On Music & Motherhood". https://thequietus.com/articles/29947-seeing-sideways-kristin-hersh-interview.

- Drumming at the edge of magic: a journey into the spirit of percussion. San Francisco, CA: Harper. 1990. p. 133.

- It just always stuck out in my mind, and I could always see it. I don't know if that makes sense, but I could always visualize what I was hearing... Yeah, it was always like weird colors." From a Nightline interview with Pharrell

- "Synesthetes: "People of the Future"". 3 March 2012. http://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/tasting-the-universe/201203/synesthetes-people-the-future.

- "Loose Women: Marina and the Diamonds". ITV Lifestyle. ITV Network. 27 April 2010. http://www.itv.com/lifestyle/loosewomen/videos/m/celebrityguests/marinaandthediamonds/.

- Bright colors falsely seen: synaesthesia and the search for transcendental knowledge. New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press. 1998. ISBN 978-0-300-06619-7.

- This is according to an article in the Russian press, Yastrebtsev V. "On N.A.Rimsky-Korsakov's color sound- contemplation." Russkaya muzykalnaya gazeta, 1908, N 39–40, pp. 842–845 (in Russian), cited by Bulat Galeyev (1999).

- Sensory Perception: Mind & Matter. Vienna: Springer Vienna. 2012. pp. 221. ISBN 978-3-211-99750-5. "I invented the colours of the vowels!"

- "The Strange Life of Nikola Tesla". pitt.edu. http://www.neuronet.pitt.edu/~bogdan/tesla/tesla.pdf.

- What Do You Care What Other People Think?. New York: Norton. 1988. p. 59.

- "Images of Synesthetes and their Perceptions of Language in Fiction". 6th Annual Meeting of the American Synesthesia Association. University of South Florida. 2006. http://www.synesthesia.info/florida.html.

- "Synaesthesia in fiction". Cortex; A Journal Devoted to the Study of the Nervous System and Behavior 46 (2): 277–278. February 2010. doi:10.1016/j.cortex.2008.11.003. PMID 19081086. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.cortex.2008.11.003

- "The shape of boubas: sound-shape correspondences in toddlers and adults". Developmental Science 9 (3): 316–322. May 2006. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7687.2006.00495.x. PMID 16669803. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2Fj.1467-7687.2006.00495.x

- "The Kiki-Bouba effect: A case of personification and ideaesthesia". Journal of Consciousness Studies 20 (1–2): 84–102. 2013.

- Synaesthesia: classic and contemporary readings. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. 1996. ISBN 978-0-631-19764-5. OCLC 59664610. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/59664610

- "Implications of synaesthesia for functionalism: Theory and experiments". Journal of Consciousness 9 (12): 5–31. 2002.

- "Is synaesthesia actually ideaesthesia? An inquiry into the nature of the phenomenon". Proceedings of the Third International Congress on Synaesthesia, Science & Art, Granada, Spain, April 26–29. 2009. http://www.danko-nikolic.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/09/Synesthesia2009-Nikolic-Ideaesthesia.pdf.

- "Semantic mechanisms may be responsible for developing synesthesia". Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 8: 509. 2014. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2014.00509. PMID 25191239. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=4137691

- "Synesthesia in science and technology: more than making the unseen visible". Current Opinion in Chemical Biology 16 (5–6): 557–563. December 2012. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2012.10.030. PMID 23183411. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3606019

- Scheff, Chaim-Meyer (1986-01-01). "Experimental model for the study of changes in the organization of human sensory information processing through the design and testing of non-invasive prosthetic devices for sensory impaired people". ACM SIGCAPH Computers and the Physically Handicapped (36): 3–10. doi:10.1145/15711.15713. ISSN 0163-5727. https://doi.org/10.1145/15711.15713.

- "Augmented Reality for the Totally Blind". http://www.seeingwithsound.com/.

- "'Visual' acuity of the congenitally blind using visual-to-auditory sensory substitution". PLOS ONE 7 (3): e33136. 16 March 2012. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0033136. PMID 22438894. Bibcode: 2012PLoSO...733136S. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3306374

- "Device Trains Blind People To 'See' By Listening". 10 July 2013. http://www.popsci.com/science/article/2013-07/synesthesia-blind?dom=PSC&loc=recent&lnk=1&con=read-full-story.

- "How well do you see what you hear? The acuity of visual-to-auditory sensory substitution". Frontiers in Psychology 4: 330. 2013. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00330. PMID 23785345. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3684791