| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sirius Huang | -- | 6604 | 2022-11-15 01:37:14 |

Video Upload Options

The Emergency in India was a 21-month period from 1975 to 1977 when Prime Minister Indira Gandhi had a state of emergency declared across the country. Officially issued by President Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed under Article 352 of the Constitution because of the prevailing "internal disturbance", the Emergency was in effect from 25 June 1975 until its withdrawal on 21 March 1977. The order bestowed upon the Prime Minister the authority to rule by decree, allowing elections to be cancelled and civil liberties to be suspended. For much of the Emergency, most of Indira Gandhi's political opponents were imprisoned and the press was censored. Several other human rights violations were reported from the time, including a mass forced sterilization campaign spearheaded by Sanjay Gandhi, the Prime Minister's son. The Emergency is one of the most controversial periods of independent India's history. The final decision to impose an emergency was proposed by Indira Gandhi, agreed upon by the president of India, and thereafter ratified by the cabinet and the parliament (from July to August 1975), based on the rationale that there were imminent internal and external threats to the Indian state.

1. Prelude

1.1. Rise of Indira Gandhi

— Congress president D. K. Barooah, c. 1974[1]

Between 1967 and 1971, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi came to obtain near-absolute control over the government and the Indian National Congress party, as well as a huge majority in Parliament. The first was achieved by concentrating the central government's power within the Prime Minister's Secretariat, rather than the Cabinet, whose elected members she saw as a threat and distrusted. For this, she relied on her principal secretary, P. N. Haksar, a central figure in Indira's inner circle of advisors. Further, Haksar promoted the idea of a "committed bureaucracy" that required hitherto-impartial government officials to be "committed" to the ideology of the ruling party of the day.

Within the Congress, Indira ruthlessly outmanoeuvred her rivals, forcing the party to split in 1969—into the Congress (O) (comprising the old-guard known as the "Syndicate") and her Congress (R). A majority of the All-India Congress Committee and Congress MPs sided with the prime minister. Indira's party was of a different breed from the Congress of old, which had been a robust institution with traditions of internal democracy. In the Congress (R), on the other hand, members quickly realised that their progress within the ranks depended solely on their loyalty to Indira Gandhi and her family, and ostentatious displays of sycophancy became routine. In the coming years, Indira's influence was such that she could install hand-picked loyalists as chief ministers of states, rather than their being elected by the Congress legislative party.

Indira's ascent was backed by her charismatic appeal among the masses that was aided by her government's near-radical leftward turns. These included the July 1969 nationalisation of several major banks and the September 1970 abolition of the privy purse; these changes were often done suddenly, via ordinance, to the shock of her opponents. She had strong support in the disadvantaged sections—the poor, Dalits, women and minorities. Indira was seen as "standing for socialism in economics and secularism in matters of religion, as being pro-poor and for the development of the nation as a whole."[2]

In the 1971 general elections, the people rallied behind Indira's populist slogan of Garibi Hatao! (abolish poverty!) to award her a huge majority (352 seats out of 518). "By the margin of its victory," historian Ramachandra Guha later wrote, Congress (R) came to be known as the real Congress, "requiring no qualifying suffix."[2] In December 1971, under her proactive war leadership, India routed arch-enemy Pakistan in a war that led to the independence of Bangladesh, formerly East Pakistan. Awarded the Bharat Ratna the next month, she was at her greatest peak; for her biographer Inder Malhotra, "The Economist's description of her as the 'Empress of India' seemed apt." Even opposition leaders, who routinely accused her of being a dictator and of fostering a personality cult, referred to her as Durga, a Hindu goddess.[3][4][5]

1.2. Increasing Government Control of the Judiciary

In 1967's Golaknath case,[6] the Supreme Court said that the Constitution could not be amended by Parliament if the changes affect basic issues such as fundamental rights. To nullify this judgement, Parliament dominated by the Indira Gandhi Congress, passed the 24th Amendment in 1971. Similarly, after the government lost a Supreme Court case for withdrawing the privy purse given to erstwhile princes, Parliament passed the 26th Amendment. This gave constitutional validity to the government's abolition of the privy purse and nullified the Supreme Court's order.

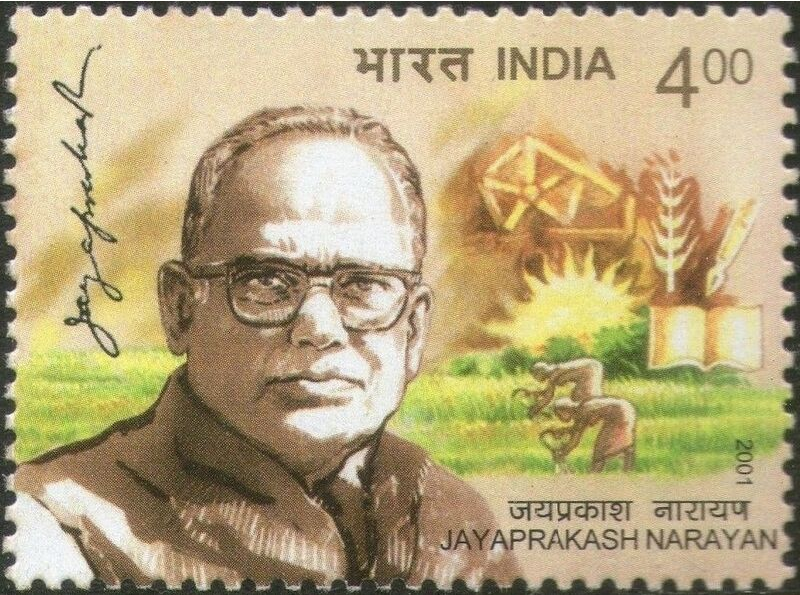

This judiciary–executive battle would continue in the landmark Kesavananda Bharati Case, where the 24th Amendment was called into question. With a wafer-thin majority of 7 to 6, the bench of the Supreme Court restricted Parliament's amendment power by stating it could not be used to alter the "basic structure" of the Constitution. Subsequently, Prime Minister Gandhi made A. N. Ray—the senior-most judge amongst those in the minority in Kesavananda Bharati—Chief Justice of India. Ray superseded three judges more senior to him—J. M. Shelat, K. S. Hegde and Grover—all members of the majority in Kesavananda Bharati. Indira Gandhi's tendency to control the judiciary met with severe criticism, both from the press and political opponents such as Jayaprakash Narayan ("JP").

1.3. Political Unrest

This led some Congress party leaders to demand a move towards a presidential system emergency declaration with a more powerful directly elected executive. The most significant of the initial such movement was the Nav Nirman movement in Gujarat, between December 1973 and March 1974. Student unrest against the state's education minister ultimately forced the central government to dissolve the state legislature, leading to the resignation of the chief minister, Chimanbhai Patel, and the imposition of President's rule. Meanwhile, there were assassination attempts on public leaders as well as the assassination of the railway minister Lalit Narayan Mishra by a bomb. All of these indicated a growing law and order problem in the entire country, which Mrs Gandhi's advisors warned her of for months.

In March–April 1974, a student agitation by the Bihar Chatra Sangharsh Samiti received the support of Gandhian socialist Jayaprakash Narayan, referred to as JP, against the Bihar government. In April 1974, in Patna, JP called for "total revolution," asking students, peasants, and labour unions to non-violently transform Indian society. He also demanded the dissolution of the state government, but this was not accepted by the centre. A month later, the railway-employees union, the largest union in the country, went on a nationwide railways strike. This strike which was led by the firebrand trade union leader George Fernandes who was the President of the All India Railwaymen's Federation. He was also the President of the Socialist Party. The strike was brutally suppressed by the Indira Gandhi government, which arrested thousands of employees and drove their families out of their quarters.[7]

1.4. Raj Narain Verdict

Raj Narain, who had been defeated in the 1971 parliamentary election by Indira Gandhi, lodged cases of election fraud and use of state machinery for election purposes against her in the Allahabad High Court. Shanti Bhushan fought the case for Narain. Indira Gandhi was also cross-examined in the High Court which was the first such instance for an Indian Prime Minister.[8]

On 12 June 1975, Justice Jagmohanlal Sinha of the Allahabad High Court found the prime minister guilty on the charge of misuse of government machinery for her election campaign. The court declared her election null and void and unseated her from her seat in the Lok Sabha. The court also banned her from contesting any election for an additional six years. Serious charges such as bribing voters and election malpractices were dropped and she was held responsible for misusing government machinery and found guilty on charges such as using the state police to build a dais, availing herself of the services of a government officer, Yashpal Kapoor, during the elections before he had resigned from his position, and use of electricity from the state electricity department.[9]

Because the court unseated her on comparatively frivolous charges, while she was acquitted on more serious charges, The Times described it as "firing the Prime Minister for a traffic ticket". Her supporters organised mass pro-Indira demonstrations in the streets of Delhi close to the Prime Minister's residence.[10] The persistent efforts of Narain were praised worldwide as it took over four years for Justice Sinha to pass judgement against the prime minister.

Indira Gandhi challenged the High Court's decision in the Supreme Court. Justice V. R. Krishna Iyer, on 24 June 1975, upheld the High Court judgement and ordered all privileges Gandhi received as an MP be stopped, and that she be debarred from voting. However, she was allowed to continue as Prime Minister pending the resolution of her appeal. Jayaprakash Narayan and Morarji Desai called for daily anti-government protests. The next day, Jayaprakash Narayan organised a large rally in Delhi, where he said that a police officer must reject the orders of government if the order is immoral and unethical as this was Mahatma Gandhi's motto during the freedom struggle. Such a statement was taken as a sign of inciting rebellion in the country. Later that day, Indira Gandhi requested a compliant President Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed to proclaim a state of emergency. Within three hours, the electricity to all major newspapers was cut and the political opposition arrested. The proposal was sent without discussion with the Union Cabinet, who only learnt of it and ratified it the next morning.[11][12]

1.5. Preventive Detention Laws

Before the emergency, the Indira Gandhi government passed draconian laws which would be used to arrest political opponents before and during emergency. One of these was the Maintanence of Internal Security Act (MISA), 1971, which was passed in May 1971 despite criticism from prominent opposition figures across partisan lines such as CPI(M)'s Jyotirmoy Basu, Jana Sangh's Atal Bihari Vajpayee, and the Anglo-Indian nominated MP Frank Anthony.[13] The Indira government also renewed the Defense of India rules, which was withdrawn in 1967,[14] Defense of India rules were given an expanded mandate 5 days into the emergency and renamed as Defense and Internal Security of India Rules. Another law, Conservation of Foreign Exchange and Prevention of Smuggling Activities Act (COFEPOSA) passed in December 1974, was also frequently used to target political opponents. [13]

2. Proclamation of the Emergency

The Government cited threats to national security, as a war with Pakistan had recently been concluded. Due to the war and additional challenges of drought and the 1973 oil crisis, the economy was in poor condition. The Government claimed that the strikes and protests had paralysed the government and hurt the economy of the country greatly. In the face of massive political opposition, desertion and disorder across the country and the party, Gandhi stuck to the advice of a few loyalists and her younger son Sanjay Gandhi, whose own power had grown considerably over the last few years to become an "extra-constitutional authority". Siddhartha Shankar Ray, the Chief Minister of West Bengal, proposed to the prime minister to impose an "internal emergency". He drafted a letter for the President to issue the proclamation based on information Indira had received that "there is an imminent danger to the security of India being threatened by internal disturbances". He showed how democratic freedom could be suspended while remaining within the ambit of the Constitution.[15][16]

After a quick question regarding a procedural matter, President Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed declared a state of internal emergency upon the prime minister's advice on the night of 25 June 1975, just a few minutes before the clock struck midnight.

As the constitution requires, Mrs Gandhi advised and President Ahmed approved the continuation of Emergency over every six months until she decided to hold elections in 1977. In 1976, Parliament voted to delay elections, something it could only do with the Constitution suspended by the Emergency.[17][18]

3. Administration

Indira Gandhi devised a '20-point' economic programme to increase agricultural and industrial production, improve public services and fight poverty and illiteracy, through "the discipline of the graveyard".[19] In addition to the official twenty points, Sanjay Gandhi declared his five-point programme promoting literacy, family planning, tree planting, the eradication of casteism and the abolition of dowry. Later during the Emergency, the two projects merged into a twenty-five-point programme.[20]

3.1. Arrests

Invoking articles 352 and 356 of the Indian Constitution, Gandhi granted herself extraordinary powers and launched a massive crackdown on civil rights and political opposition. The Government used police forces across the country to place thousands of protestors and strike leaders under preventive detention. Vijayaraje Scindia, Jayaprakash Narayan, Raj Narain, Morarji Desai, Charan Singh, Jivatram Kripalani, Atal Bihari Vajpayee, Lal Krishna Advani, Arun Jaitley,[21] Satyendra Narayan Sinha, Gayatri Devi, the dowager queen of Jaipur,[22] and other protest leaders were immediately arrested. Organisations like the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and Jamaat-e-Islami, along with some political parties, were banned. Numerous Communist leaders[clarification needed] were arrested along with many others involved with their party. Congress leaders who dissented against the Emergency declaration and amendment to the constitution, such as Mohan Dharia and Chandra Shekhar, resigned their government and party positions and were thereafter arrested and placed under detention.[23][24]

Cases like the Baroda dynamite case and the Rajan case became exceptional examples of atrocities committed against civilians in independent India.

3.2. Laws, Human Rights and Elections

Elections for the Parliament and state governments were postponed. Gandhi and her parliamentary majorities could rewrite the nation's laws since her Congress party had the required mandate to do so – a two-thirds majority in the Parliament. And when she felt the existing laws were 'too slow', she got the President to issue 'Ordinances' – a law-making power in times of urgency, invoked sparingly – completely bypassing the Parliament, allowing her to rule by decree. Also, she had little trouble amending the Constitution that exonerated her from any culpability in her election-fraud case, imposing President's Rule in Gujarat and Tamil Nadu, where anti-Indira parties ruled (state legislatures were thereby dissolved and suspended indefinitely), and jailing thousands of opponents. The 42nd Amendment, which brought about extensive changes to the letter and spirit of the Constitution, is one of the lasting legacies of the Emergency. In the conclusion of his Making of India's Constitution, Justice Khanna writes:

If the Indian constitution is our heritage bequeathed to us by our founding fathers, no less are we, the people of India, the trustees, and custodians of the values which pulsate within its provisions! A constitution is not a parchment of paper, it is a way of life and has to be lived up to. Eternal vigilance is the price of liberty and in the final analysis, its only keepers are the people. The imbecility of men, history teaches us, always invites the impudence of power.[25]

A fallout of the Emergency era was the Supreme Court laid down that, although the Constitution is amenable to amendments (as abused by Indira Gandhi), changes that tinker with its basic structure[26] cannot be made by the Parliament. (see Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala)[27]

In the Rajan case, P. Rajan of the Regional Engineering College, Calicut, was arrested by the police in Kerala on 1 March 1976,[28] tortured in custody until he died and then his body was disposed of and was never recovered. The facts of this incident came out owing to a habeas corpus suit filed in the Kerala High Court.[29][30]

Many cases where teens were arrested and imprisoned have come into light, one such example is of Dilip Sharma who aged 16 was arrested and imprisoned for over 11 months. He was released based on Patna High Court's judgment on 29 July 1976.[31]

3.3. Economics

Christophe Jaffrelot considers the economic policy of the emergency regime to be corporatist, five programmes in the 20 point programme were aimed at benefiting the middle classes and industrialists, these included- liberalising investment procedures, introducing new schemes for workers' associations in industry, implementing a national permit scheme for road transport, tax breaks to the middle class by exempting anyone earning under Rs. 8,000 from income taxes, and an austerity programme to reduce public spending.[13]

Trade Unions and Worker's Rights

The emergency regime cracked down on trade unionism, banned strikes, imposed wage freezes, and phased out wage bonuses.[32] The largest trade unions in the country at the time such as the Congress' INTUC, CPI's AITUC, and Socialist affiliated HMS were made to comply with the new regime, while the CPI(M)'s CITU continued it's opposition for which it had 20 of it's leaders arrested. State governments were asked to form bipartite councils composing of representatives of the workers and the management for firms having more than 500 employees, similar apex bipartite committes were formed by the Centre for major public sector industries, while a National Apex Board was set up for the private industries. These were meant to give a veneer of worker participation in decision making, but were in reality stacked in the favour of the management, and tasked with increasing "productivity" by cutting holidays (including Sundays), bonuses, agreeing to wage freeze, and allowing layoffs.[13][32]

Worker demonstrations that took place during the emergency were subject to heavy state repression, such as when the AITUC organised a one-day strike to protest slashing of bonuses in January 1976, to which the state responded by arresting 30,000-40,000 workers. In another such instance the 8,000 workers of the Indian Telephone Industries (a Banglore based state-owned company) took part in a peaceful sit-in protest in response to the management reneging it's promise of 20% bonus to just 8%, they found themselves lathi charged by the police who also arrested a few hundred of them.[13]

Coal miners were forced to work in abysmal conditions with irregular pay, collieries were made to run for all the seven days of a week, complaints of workers and unions about the abysmal and dangerous working conditions were ignored and met with state repression. These terrible workplace conditions led to the deadliest mining disaster in Indian history on 27th December 1975, at Chasnala coal mine near Dhanbad which claimed the lives of 375 miners due to more than 100 million gallons of water flooding the mine. This was the 222nd such accident that year, the previous incidents having claimed 288 lives.[13]

Inflation and Price control

The emergency government enjoyed a degree of popular support due to lower prices of goods and services at least during 1975. This was due to many reasons such as RBI's policy of putting in place a 6 percent ceiling on annual money supply growth months before the emergency, record monsoon in the year of 1975 leading to record harvest of foodgrains which led to food prices declining, increased import of grains, and reduced demand due to cutting of worker's wages and bonuses. In addition to this half of the dearness allowance of workers was withheld as part of the Wage Freeze act as compulsory deposits to combat inflation. However these reduced prices only lasted till March 1976 when the prices of commodities started to go up again, on account of foodgrain production declining by 7.9%. Between 1st April and 6th October of 1976 the wholesole price index rose by 10%, in which the price of rice rose by 8.3%, groundnut oil rose by 48%, while the prices of industrial raw materials as a group rose by 29.3%.[13][33]

Tax Policy

The emergency regime exempted those earning between Rs 6,000-8,000 from taxation, provided tax breaks for those earning between Rs 8,000-15,000 in the range of Rs 45-264. There were only 3.8 million (38 lakh) tax payers in the country at the time. Wealth taxes were also cut from 8% to 2.5% while the income taxes on those earning more than Rs 100,000 were reduced from 77% to 66%. This was expected to lower the government's revenue by Rs 3.08-3.25 billion. To compensate for this indirect taxes grew, the ration of indirect taxes to direct taxes was at 5.31 in 1976. Despite this there was a loss in revenue of Rs 400 million (40 crores), to compensate for this the Indira Gandhi government decided to cut spending in education and social welfare.[13]

3.4. Forced Sterilisation

In September 1976, Sanjay Gandhi initiated a widespread compulsory sterilisation programme to limit population growth. The exact extent of Sanjay Gandhi's role in the implementation of the programme is disputed, with some writers[34][35][36][37] holding Gandhi directly responsible for his authoritarianism, and other writers[38] blaming the officials who implemented the programme rather than Gandhi himself. It is clear that international pressure from the United States, United Nations, and World Bank played a role in the implementation of these population control measures.[39] Rukhsana Sultana was a socialite known for being one of Sanjay Gandhi's close associates[40] and she gained a lot of notoriety in leading Sanjay Gandhi's sterilisation campaign in Muslim areas of old Delhi.[41][42][43] The campaign primarily involved getting males to undergo vasectomy. Quotas were set up that enthusiastic supporters and government officials worked hard to achieve. There were allegations of coercion of unwilling candidates too.[44] In 1976–1977, the programme led to 8.3 million sterilisations, most of them forced, up from 2.7 million the previous year. The bad publicity led many 1977 governments to stress that family planning is entirely voluntary.[45]

- Kartar, a cobbler, was taken to a Block Development Officer (BDO) by six policemen, where he was asked how many children he had. He was forcefully taken for sterilisation in a jeep. En route, the police forced a man on the bicycle into the jeep because he was not sterilised. Kartar had an infection and pain because of the procedure and could not work for months.[46]

- Shahu Ghalake, a peasant from Barsi in Maharashtra, was taken for sterilisation. After mentioning that he was already sterilised, he was beaten. A sterilisation procedure was undertaken on him for a second time.[46]

- Hawa Singh, a young widower, from Pipli was taken from the bus against his will and sterilised. The ensuing infection took his life.[46]

- Harijan, a 70-year-old with no teeth and bad eyesight, was sterilised forcefully.[46]

- Ottawa, a village 80 kilometres south of Delhi, woke up to the police loudspeakers at 03:00. Police gathered 400 men at the bus stop. In the process of finding more villagers, police broke into homes and looted. A total of 800 forced sterilisations were done.[46]

- In Muzaffarnagar, Uttar Pradesh, on 18 October 1976, police picked up 17 people, of which two were over 75 and two under 18. Hundreds of people surrounded the police station demanding they free captives. The police refused to release them and used tear gas shells. The crowd retaliated by throwing stones and to control the situation, the police fired on the crowd. 30 people died as a result.[46]

3.5. Demolitions

Demolitions in Delhi

Delhi served as the epicenter of Sanjay Gandhi's "urban renewal" programme, aided in large part by DDA vice-president Jagmohan Malhotra who himself had a desire to "beautify" the city. During the emergency Jagmohan emerged as the single most powerful person in the DDA, and went to extra-ordinary lengths to do the bidding of Sajay Gandhi, as the Shah commission notes-

"Shri Jagmohan during the emergency, became a law unto himself and went about doing the biddings of Shri Sanjay Gandhi without care or concern for the miseries of the people affected thereby"[47]

In total 700,000 or 7 lakhs people in Delhi were displaced due to the demolitions carried out in Delhi.

| Period | Structures Demolished by | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Emergency | DDA | MCD | NDMC | Total |

| 1973 | 50 | 320 | 5 | 375 |

| 1974 | 680 | 354 | 25 | 1,059 |

| 1975 (up to June) | 190 | 149 | 27 | 366 |

| Total | 920 | 823 | 57 | 1,800 |

| Emergency | ||||

| 1975 | 35,767 | 4,589 | 796 | 41,252 |

| 1976 | 94,652 | 4,013 | 408 | 99,073 |

| 1977 (up to 23rd March) | 7,545 | 96 | - | 7,641 |

| Year unspecified but during the emergency |

- | 1,962 | 177 | 2,139 |

| Total | 137,964 | 10,760 | 1,381 | 150,105 |

Demolisions outside Delhi

During the Emergency various state governments also carried out demolitions to clear "encroachments", undertaken to please Sanjay Gandhi. In many of these cases resisdents were given very short notices, state governments like those of Bihar and Haryana avoided giving official notices to the residents of "encroachments" to avoid a case in a civil court, instead they notified them through public channels, or in the case of Haryana through drum beats, and in some cases gave no prior information. States passed various laws to aid them in this process such as Maharashtra Vacant Land Act 1975, Bihar Public Encroachment Act 1975, and Madhya Pradesh Land Revenue Code (Amendment) Act. These demolitions were often accompanied by the police to threaten the residents with arrest under MISA or DIR. In Mahrashtra Mumbai alone saw demolitions of 12,000 huts, while Pune saw demolitions of 1285 huts and 29 shops.[49]

3.6. Criticism of the Government

Criticism and accusations from the Emergency era may be grouped as:

- Detention of people by police without charge or notification of families

- Abuse and torture of detainees and political prisoners

- Use of public and private media institutions, like the national television network Doordarshan, for government propaganda

- During the Emergency, Sanjay Gandhi asked the popular singer Kishore Kumar to sing for a Congress party rally in Bombay, but he refused.[50] As a result, Information and broadcasting minister Vidya Charan Shukla put an unofficial ban on playing Kishore Kumar songs on state broadcasters All India Radio and Doordarshan from 4 May 1976 till the end of Emergency.[51][52]

- Forced sterilisation.

- Destruction of the slum and low-income housing in the Turkmen Gate and Jama Masjid area of old Delhi.

- Large-scale and illegal enactment of new laws (including modifications to the Constitution).

4. Resistance Movements

4.1. The Role of RSS

Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, which was seen close to opposition leaders, was also banned.[53] Police clamped down on the organisation and thousands of its workers were imprisoned.[54] The RSS defied the ban and thousands participated in Satyagraha (peaceful protests) against the ban and the curtailment of fundamental rights. Later, when there was no letup, the volunteers of the RSS formed underground movements for the restoration of democracy. Literature that was censored in the media was clandestinely published and distributed on a large scale and funds were collected for the movement. Networks were established between leaders of different political parties in the jail and outside for the co-ordination of the movement.[55]

The attitude of senior RSS leaders about the Emergency was divided: several opposed it staunchly, others apologised and were released, and several senior leaders, notably Balasaheb Deoras sought an accommodation with Sanjay and Indira Gandhi.[56][57] Nanaji Deshmukh and Madan Lal Khurana managed to escape the police and led the RSS resistance to the Emergency. As did Subramanian Swamy.[58]

Zonal RSS leaders also authorised Eknath Ramakrishna Ranade to quietly enter into a dialogue with Indira Gandhi.

Indira Gandhi had helped Ranade, who had been second to Golwalkar in the RSS hierarchy, in numerous projects to commemorate Vivekananda. She had nominated Ranade to the governing council of the Indian Council for Cultural Relations, and the two used ICCR as a facade to conduct secret one-on-one negotiations.[58]

Arun Jaitley, Student leader and head of the RSS affiliated ABVP (Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad) in Delhi, was among the first to be arrested, and he spent the entire Emergency in jail. However, other ABVP leaders such as Balbir Punj and Prabhu Chawla pledged allegiance to Indira Gandhi's Twenty Point Programme and Sanjay Gandhi's Five Point Programme, in return for staying out of jail.[58]

In November 1976, over 30 leaders of the RSS, led by Madhavrao Muley, Dattopant Thengadi, and Moropant Pingle, wrote to Indira Gandhi, promising support to the Emergency if all RSS workers were released from prison. Their 'Document of Surrender', to take effect from January 1977, was processed by H.Y. Sharada Prasad.[58]

On his return from his meeting with Om Mehta, Vajpayee ordered the cadres of the ABVP to apologise unconditionally to Indira Gandhi. The ABVP students refused.

The RSS 'Document of Surrender', was also confirmed by Subramanian Swamy in his article: “...I must add that not all in the RSS were in a surrender mode...But a tearful Muley told me in early November 1976 and I had better escape abroad again since the RSS had finalised the Document of Surrender to be signed in end January 1977, and that on Mr. Vajpayee's insistence I would be sacrificed to appease an irate Indira and a fulminating Sanjay....”.[58]

4.2. Sikh Opposition

Shortly after the declaration of the Emergency, the Sikh leadership convened meetings in Amritsar where they resolved to oppose the "fascist tendency of the Congress".[59] The first mass protest in the country, known as the "Campaign to Save Democracy" was organised by the Akali Dal and launched in Amritsar, 9 July. A statement to the press recalled the historic Sikh struggle for independence under the Mughals, then under the British, and voiced concern that what had been fought for and achieved was being lost. The police were out in force for the demonstration and arrested the protestors, including the Shiromani Akali Dal and Shiromani Gurdwara Prabandhak Committee (SGPC) leaders.

The question before us is not whether Indira Gandhi should continue to be prime minister or not. The point is whether democracy in this country is to survive or not.[60]

According to Amnesty International, 140,000 people had been arrested without trial during the twenty months of Gandhi's Emergency. Jasjit Singh Grewal estimates that 40,000 of them came from India's two per cent Sikh minority.[61]

4.3. The Role of CPI(M)

Members of CPI(M) were identified and arrested all over India. Raids were conducted in houses suspected to be sympathetic of CPI(M) or the opposition to the emergency.

Those jailed during the Emergency include the current general secretary of the Communist Party of India (Marxist), Sitaram Yechury, and his predecessor, Prakash Karat. Both were then leaders of the Students Federation of India, the party's student wing.

Other Communist Party of India (Marxist) members to be jailed included the current Chief Minister of Kerala Pinarayi Vijayan, then a young MLA. He was taken into custody during the Emergency and subjected to third degree methods. On his release, Pinarayi reached the Assembly and made an impassionate speech holding up the blood-stained shirt he wore when in police custody, causing serious embarrassment to the then C. Achutha Menon government.[62]

Hundreds of Communists, whether from the Communist Party of India (Marxist), other Marxist parties, or the Naxalites, were arrested during the Emergency.[63] Some were tortured or, as in the case of the Kerala student P Rajan, killed.

5. Elections of 1977

On 18 January 1977, Gandhi called fresh elections for March and released a few political prisoners, many remained in prison even after she was ousted, though the Emergency officially ended on 21 March 1977. The opposition Janata movement's campaign warned Indians that the elections might be their last chance to choose between "democracy and dictatorship."

In the Lok Sabha elections, held in March, Indira Gandhi and Sanjay both lost their Lok Sabha seats, as did all the Congress candidates in northern states such as Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. Many Congress Party loyalists deserted Mrs Gandhi. The Congress was reduced to just 153 seats, 92 of which were from four of the southern states. The Janata Party's 298 seats and its allies' 47 seats (of a total 542) gave it a massive majority. Morarji Desai became the first non-Congress Prime Minister of India.

Voters in the electorally largest state of Uttar Pradesh, historically a Congress stronghold, turned against Gandhi and her party failed to win a single seat in the state. Dhanagare says the structural reasons behind the discontent against the Government included the emergence of the strong and united opposition, disunity and weariness inside Congress, an effective underground opposition, and the ineffectiveness of Gandhi's control of the mass media, which had lost much credibility. The structural factors allowed voters to express their grievances, notably their resentment of the emergency and its authoritarian and repressive policies. One grievance often mentioned was the 'nasbandi' (vasectomy) campaign in rural areas. The middle classes also emphasised the curbing of freedom throughout the state and India.[64] Meanwhile, Congress hit an all-time low in West Bengal because of the poor discipline and factionalism among Congress activists as well as the numerous defections that weakened the party.[65] Opponents emphasised the issues of corruption in Congress and appealed to a deep desire by the voters for fresh leadership.[66]

6. The Tribunal

The efforts of the Janata administration to get government officials and Congress politicians tried for Emergency-era abuses and crimes were largely unsuccessful due to a disorganised, over-complex and politically motivated process of litigation. The Thirty-eighth Amendment of the Constitution of India, put in place shortly after the outset of the Emergency and which among other things prohibited judicial reviews of states of emergencies and actions taken during them, also likely played a role in this lack of success. Although special tribunals were organised and scores of senior Congress Party and government officials arrested and charged, including Mrs Gandhi and Sanjay Gandhi, police were unable to submit sufficient evidence for most cases, and only a few low-level officials were convicted of any abuses.

7. Legacy

The Emergency lasted 21 months, and its legacy remains intensely controversial. A few days after the Emergency was imposed, the Bombay edition of The Times of India carried an obituary that read

A few days later censorship was imposed on newspapers. The Delhi edition of the Indian Express on 28 June, carried a blank editorial, while the Financial Express reproduced in large type Rabindranath Tagore's poem "Where the mind is without fear".[69]

However, the Emergency also received support from several sections. It was endorsed by social reformer Vinoba Bhave (who called it Anushasan Parva, a time for discipline), industrialist J. R. D. Tata, writer Khushwant Singh, and Indira Gandhi's close friend and Orissa Chief Minister Nandini Satpathy. However, Tata and Satpathy later regretted that they spoke in favour of the Emergency.[70][71]

In the book JP Movement and the Emergency, historian, Bipan Chandra wrote, "Sanjay Gandhi and his cronies like Bansi Lal, Minister of Defence at the time, were keen on postponing elections and prolonging the emergency by several years. In October – November 1976, an effort was made to change the basic civil libertarian structure of the Indian Constitution through the 42nd amendment to it. ... The most important changes were designed to strengthen the executive at the cost of the judiciary, and thus disturb the carefully crafted system of Constitutional checks and balance between the three organs of the government."[72]

8. In Culture

8.1. Literature

- Writer Rahi Masoom Raza criticised the Emergency through his novel Qatar bi Aarzoo.[73]

- Shashi Tharoor portrays the Emergency allegorically in his The Great Indian Novel (1989), describing it as "The Siege". He also authored a satirical play on the Emergency, Twenty-Two Months in the Life of a Dog, that was published in his The Five-Dollar Smile and Other Stories.

- A Fine Balance and Such a Long Journey by Rohinton Mistry take place during the Emergency and highlight many of the abuses that occurred during that period, largely through the lens of India's small but culturally influential Parsi minority.

- Rich Like Us by Nayantara Sahgal is partly set during the Emergency and deals with themes such as political corruption and oppression in the context of the event.[74]

- Booker Prize-winner Midnight's Children by Salman Rushdie, has the protagonist, Saleem Sinai, in India during the Emergency. His home in a low-income area, called the "magician's ghetto", is destroyed as part of the national beautification program. He is forcibly sterilised as part of the vasectomy program. The principal antagonist of the book is "the Widow" (a likeness that Indira Gandhi successfully sued Rushdie for). There was one line in the book that repeated an old Indian rumour that Indira Gandhi's son didn't like his mother because he suspected her of causing the death of his father. As this was a rumour; there was no substantiation to be found.[75]

- India: A Wounded Civilization, a book by V. S. Naipaul is also oriented around The Emergency.[76]

- The Plunge, an English-language novel by Sanjeev Tare, is the story told by four youths studying at Kalidas College in Nagpur. They tell the reader what they went through during those politically turbulent times.

- The Malayalam-language novel Delhi Gadhakal (Tales from Delhi) by M. Mukundan highlights many waves of abuse that occurred during the Emergency including forced sterilisation of men and the destruction of houses and shops owned by Muslims in Turkmen Gate.

- Brutus, You!, a book by Chanakya Sen, is based on internal politics of Jawaharlal Nehru University, Delhi during the period of Emergency.

- Vasansi Jirnani, a play by Torit Mitra, is inspired by Ariel Dorfman's Death and the Maiden and effects of the Emergency.

- The Tamil-language novel Marukkozhunthu Mangai (Girl with Fragrant Chinese Mugwort ) by Ra. Su. Nallaperumal which is based on the history of Pallavas Dynasty and a popular uprising in Kanchi during 725 A.D. It explains how the widowed Queen and the Princess kill the freedom of the people. Most of the incidents described in the novel resemble the Emergency period. Even the name of the characters in the novel is similar to Mrs Gandhi and her family.

- The Malayalam-language autobiographical diary by political activist R. C. Unnithan, penned while the author was imprisoned as a political prisoner during the Emergency under MISA for sixteen months at Poojappura state prison in Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, gives a personal account of his travails during the dark days of Indian democracy.

- The Tamil-language novel Karisal'' (Black Soil) by Ponneelan deals with the socio-political changes during the period.

- The Tamil-language novel Ashwamedam by Ramachandra Vaidyanath deals with the political movements during the period.

- In 2001, in the book Life of Pi by Canadian author, Yann Martel , Pi's father decides to sell the zoo and move his family to Canada , around the same time of the Emergency.

- The graphic novel Delhi Calm,[77] by Vishwajyoti Ghosh, was published in 2010, that narrates the events of the Emergency.

8.2. Film

- Gulzar's Aandhi (1975) was banned, because the film was supposedly based on Indira Gandhi.[78]

- Amrit Nahata's film Kissa Kursi Ka (1977) a bold spoof on the Emergency, where Shabana Azmi plays 'Janata' (the public) a mute, dumb protagonist, was subsequently banned and reportedly, all its prints were burned by Sanjay Gandhi and his associates at his Maruti factory in Gurgaon.[79]

- Yamagola a 1977 Telugu film (Hindi re-make Lok Parlok) spoofs the emergency issues.

- I. S. Johar's 1978 Bollywood Film Nasbandi is sarcasm on the sterilisation drive of the Government of India, where each one of the characters is trying to find sterilisation cases. The film was banned after its release due to its portrayal of the Indira Gandhi government.

- Although Satyajit Ray's 1980 film Hirak Rajar Deshe was a children's comedy, it was a satire on the Emergency where the ruler forcefully mind washes the poor people.

- The 1985 Malayalam film Yathra directed by Balu Mahendra has the human rights violations by the police during the Emergency as its main plotline.

- 1988 Malayalam film Piravi is about a father searching for his son Rajan, who had been arrested by the police (and allegedly killed in custody).

- The 2005 Hindi film Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi is set against the backdrop of the Emergency. The film, directed by Sudhir Mishra, also tries to portray the growth of the Naxalite movement during the Emergency era. The movie tells the story of three youngsters in the 1970s when India was undergoing massive social and political changes.

- The 2012 Marathi film Shala discusses the issues related to the Emergency.

- The critically acclaimed 2012 film adaptation, Life of Pi, uses the Emergency as the backdrop of which Pi's father decides to sell the zoo and move his family to Canada .

- Midnight's Children, a 2012 adaptation of Rushdie's novel, created widespread controversy due to the negative portrayal of Indira Gandhi and other leaders. The film was not shown at the International Film Festival of India and was banned from further screening at the International Film Festival of Kerala where it was premièred in India.

- Indu Sarkar, 2017 Hindi political thriller film about the emergency, directed by Madhur Bhandarkar.

- 21 Months of Hell, documentary film about the torture methods performed by the police.

- Sarpatta Parambarai, 2021 Tamil language sports film which is set in the backdrop of the Emergency and shows the arrest of DMK political members.

References

- Guha, p. 467

- Guha, p. 439

- Malhotra, p. 141

- Hellmann-Rajanayagam, Dagmar (2013). "The Pioneers: Durga Amma, The Only Man in the Cabinet". Dynasties and Female Political Leaders in Asia: Gender, Power and Pedigree. ISBN 978-3-643-90320-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=UKBcLhCxSvQC&pg=PA27. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- Puri, Balraj (1993). "Indian Muslims since Partition". Economic and Political Weekly 28 (40): 2141–2149.

- https://indiankanoon.org/doc/120358/

- Doshi, Vidhi (9 March 2017). "Indira Jaising: "In India, you can't even dream of equal justice. Not at all"". The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development-professionals-network/2017/mar/09/indira-jaising-india-is-in-crisis-this-fight-is-going-to-go-on.

- "Justice Sinha, who set aside Indira Gandhi's election, dies at 87". The Indian Express. 2008-03-22. http://www.expressindia.com/latest-news/aaJustice-Sinha-who-set-aside-Indira-Gandhis-election-dies-at-87/287227/.

- Kuldip Singh (1995-04-11). "OBITUARY: Morarji Desai". The Independent. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/people/obituary-morarji-desai-1615165.html.

- Katherine Frank (2001). Indira: The Life of Indira Nehru Gandhi. HarperCollins. pp. 372–373. ISBN 0-00-255646-4.

- "Indian Emergency of 1975-77". Mount Holyoke College. http://www.mtholyoke.edu/~ghosh20p/page1.html.

- "The Rise of Indira Gandhi". Library of Congress Country Studies. http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?frd/cstdy:@field(DOCID+in0029).

- Christophe Jaffrelot, Pratinav Anil (2021). India's first dictatorship : the emergency, 1975 -1977. Noida. ISBN 978-93-90351-60-2. OCLC 1242023968. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1242023968.

- Mussells, Premila Menon (1980). Democracy and Emergency rule in India : (Thesis thesis). https://shareok.org/handle/11244/4750

- NAYAR, KULDIP (25 June 2000). Yes, Prime Minister . The Indian Express. http://www.indianexpress.com/ie/daily/20000713/e1.htm

- "[Explained Why Did Indira Gandhi Impose Emergency In 1975?"]. thehansindia. https://www.thehansindia.com/hans/opinion/news-analysis/why-did-indira-gandhi-impose-emergency-in-1975-630015.

- Malhotra, Inder (2014-08-04). "The abrupt end of Emergency" (in en). https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/the-abrupt-end-of-emergency/.

- Times, William Borders; Special to The New York (1976-02-05). "DELAY IN ELECTION IS VOTED IN INDIA" (in en-US). The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. https://www.nytimes.com/1976/02/05/archives/delay-in-election-is-voted-in-india-lower-house-over-strong.html.

- Jaitely, Arun (5 November 2007) – "A tale of three Emergencies: real reason always different", The Indian Express http://www.indianexpress.com/news/a-tale-of-three-emergencies-real-reason-always-different/235992/0

- Tarlo, Emma (2001). Unsettling memories : narratives of the emergency in Delhi. University of California Press. pp. 27–28. ISBN 0-520-23122-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=3IO1WB2H8UUC&q=+%22five+point%22++&pg=PR5. Retrieved 28 June 2016.

- Today, India. "Arun Jaitley: From Prison to Parliament". http://indiatoday.intoday.in/story/arun-jaitley-from-prison-to-parliament/1/369679.html.

- Malgonkar, Manohar (1987). The Last Maharani of Gwalior: An Autobiography By Manohar Malgonkar. pp. 233, 242–244. ISBN 9780887066597. https://books.google.com/books?id=sbNaTBhe5nUC&q=Gayatri+Devi&pg=PA233.

- Austin, Granville (1999). Working a Democratic Constitution - A History of the Indian Experience. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. p. 320. ISBN 019565610-5. https://archive.org/details/workingdemocrati00aust.

- Narasimha Rao, the Best Prime Minister? by Janak Raj Jai - 1996 - Page 101

- H. R. Khanna (2008). Making of India's Constitution. Eastern Book Co, Lucknow, 1981. ISBN 978-81-7012-108-4.

- V. Venkatesan, Revisiting a verdict Frontline (vol. 29 – Issue 01 :: 14–27 Jan 2012) http://www.hindu.com/fline/fl2901/stories/20120127290107100.htm

- "The case that saved Indian democracy". The Hindu (24 April 2013). Retrieved 4 September 2013. http://www.thehindu.com/opinion/op-ed/the-case-that-saved-indian-democracy/article4647800.ece

- PUCL Archives, Oct 1981, Rajan. http://www.pucl.org/from-archives/81oct/rajan.htm

- Rediff.com, Report dated 26 June 2000. http://news.rediff.com/report/2000/jun/26/george.htm

- "Fresh probe in Rajan case sought ". The Hindu, 25 January 2011. https://web.archive.org/web/20110301082725/http://www.hindu.com/2011/01/25/stories/2011012561990500.htm

- "PALPAL INDIA January2017". https://issuu.com/palpalindia.com/docs/january2017.

- Rudolph, Lloyd I.; Rudolph, Susanne Hoeber (1978-04-01). "To the Brink and Back: Representation and the State in India" (in en). Asian Survey 18 (4): 379–400. doi:10.2307/2643401. ISSN 0004-4687. https://online.ucpress.edu/as/article/18/4/379/21348/To-the-Brink-and-Back-Representation-and-the-State.

- Toye, J. F. J. (1977-04-01). "Economic trends and policies in India during the Emergency" (in en). World Development 5 (4): 303–316. doi:10.1016/0305-750X(77)90036-5. ISSN 0305-750X. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0305750X77900365.

- Vinay Lal. "Indira Gandhi". http://www.sscnet.ucla.edu/southasia/History/Independent/Indira.html. ""Sanjay Gandhi, started to run the country as though it were his fiefdom and earned the fierce hatred of many whom his policies had victimised. He ordered the removal of slum dwellings, and in an attempt to curb India's growing population, initiated a highly resented programme of forced sterilisation.""

- Subodh Ghildiyal (29 December 2010). "Cong blames Sanjay Gandhi for Emergency 'excesses'". The Times of India. http://articles.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/2010-12-29/india/28661327_1_slum-clearance-sanjay-gandhi-sterilization. ""Sanjay Gandhi's rash promotion of sterilization and forcible clearance of slums ... sparked popular anger""

- Kumkum Chadha (4 January 2011). "Sanjay's men and women". http://blogs.hindustantimes.com/just-people/2011/01/04/sanjays-men-and-women/. ""The Congress, on the other hand, charges Sanjay Gandhi of "over-enthusiasm" in dealing with certain programmes and I quote yet again: "Unfortunately, in certain spheres, over-enthusiasm led to compulsion in the enforcement of certain programmes like compulsory sterilisation and clearance of slums. Sanjay Gandhi had by then emerged as a leader of great significance.".""

- "Sanjay Gandhi worked in an authoritarian manner: Congress book". 28 December 2010. http://www.zeenews.com/news677226.html.

- India: The Years of Indira Gandhi. Brill Academic Pub. 1988. ISBN 9788131734650. https://books.google.com/books?id=8v7Vr2iQUHkC&pg=PA171.

- Green, Hannah Harris. "The legacy of India's quest to sterilise millions of men" (in en). https://qz.com/india/1414774/the-legacy-of-indias-quest-to-sterilise-millions-of-men/.

- "Tragedy at Turkman Gate: Witnesses recount horror of Emergency". 28 June 2015. https://www.hindustantimes.com/india/tragedy-at-turkman-gate-witnesses-recount-horror-of-emergency/story-UD6kxHbROYSBMlDbjQLYpJ.html.

- "Those were the days". http://indiatoday.intoday.in/story/rukhsana-sultana-the-chief-glamour-girl-of-the-emergency/1/435570.html.

- "Emergency Duty". http://indiatoday.intoday.in/story/rukhsana-sultana-an-exotic-female/1/155841.html.

- "THE NIGHT OF THE LONG KNIVES". https://www.telegraphindia.com/1150628/jsp/7days/story_28218.jsp.

- Gwatkin, Davidson R. 'Political Will and Family Planning: The Implications of India's Emergency Experience', in: Population and Development Review, 5/1, 29–59;

- Carl Haub and O. P. Sharma, "India's Population Reality: Reconciling Change and Tradition," Population Bulletin (2006) 61#3 pp 3+. online https://www.questia.com/PM.qst?a=o&d=5045013834

- Mehta, Vinod (1978). The Sanjay Story. Harper Collins Publishers India.

- Shah Commission Of Inquiry Interim Report II. pp. 118. http://archive.org/details/ShahCommissionOfInquiryInterimReportII.

- Shah Commission Of Inquiry Interim Report II. pp. 78. http://archive.org/details/ShahCommissionOfInquiryInterimReportII.

- Shah Commission Of Inquiry 3rd Final Report. pp. 208-217. http://archive.org/details/ShahCommissionOfInquiry3rdFinalReport.

- Vinay Kumar (19 August 2005). "The spark that he was". The Hindu. http://www.hindu.com/fr/2005/08/19/stories/2005081902110400.htm.

- "A Star's Real Stripes". The Times of India. 25 March 2012. http://articles.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/2012-03-25/special-report/31236427_1_political-films-bollywood-hindi-film-industry.

- Sharma, Dhirendra (1997). The Janata (people's) Struggle. Philosophy and Social Action. p. 76.

- Jaffrelot Christophe, Hindu Nationalism, 1987, 297, Princeton University Press, ISBN:0-691-13098-1, ISBN:978-0-691-13098-9

- Chitkara M G, Hindutva, Published by APH Publishing, 1997 ISBN:81-7024-798-5, ISBN:978-81-7024-798-2

- Post Independence India, Encyclopedia of Political Parties,2002, Published by Anmol Publications PVT. LTD, ISBN:81-7488-865-9, ISBN:978-81-7488-865-5

- Abdul Gafoor Abdul Majeed Noorani (2000). The RSS and the BJP: A Division of Labour. LeftWord Books. pp. 31–32. ISBN 978-81-87496-13-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=6PnBFW7cdtsC&pg=PT8.

- Christophe Jaffrelot (1999). The Hindu Nationalist Movement and Indian Politics: 1925 to the 1990s : Strategies of Identity-building, Implantation and Mobilisation (with Special Reference to Central India). Penguin Books India. pp. 273–274. ISBN 978-0-14-024602-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=iVsfVOTUnYEC&pg=PR7.

- https://theprint.in/opinion/rss-leaders-deserted-jayaprakash-resistance-during-indira-emergency/448294/%3famp

- J.S. Grewal, The Sikhs of Punjab,(Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1990) 213

- Gurmit Singh, A History of Sikh Struggles, New Delhi, Atlantic Publishers and Distributors, 1991, 2:39

- J.S. Grewal, The Sikhs of Punjab, (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1990) 214; Inder Malhotra, Indira Gandhi: A Personal and Political Biography,(London/Toronto, Hodder and Stoughton, 1989) 178

- "പിണറായിയുടെ 1977 മാര്ച്ച് 30 ലെ നിയമസഭ പ്രസംഗം". https://www.asianetnews.com/magazine/pinarayi-vijayan-kerala-assembly-speech.

- Nair, C. Gouridasan (21 May 2016). "Pinarayi Vijayan: Steeled by a life of relentless adversities". The Hindu. http://www.thehindu.com/elections/kerala2016/pinarayi-vijayan-steeled-by-a-life-of-relentless-adversities/article8627081.ece/amp.

- D.N. Dhanagare, "Sixth Lok Sabha Election in Uttar Pradesh – 1977: The End of the Congress Hegemony," Political Science Review (1979) 18#1 pp 28–51

- Mira Ganguly and Bangendu Ganguly, "Lok Sabha Election, 1977: The West Bengal Scene," Political Science Review (1979) 18#3 pp 28–53

- M.R. Masani, "India's Second Revolution," Asian Affairs (1977) 5#1 pp 19–38.

- Joseph, Manu (20 May 2007). "How Indians Protest." The Times of India (timesofindia.indiatimes.com). Retrieved 10 November 2018. http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/home/stoi/How-Indians-Protest/articleshow/2061978.cms

- Austin, Granville (1999). Working a democratic constitution: the Indian experience. Oxford University Press. p. 295. ISBN 0-19-564888-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=r42bAAAAMAAJ.

- Arputham, Avneesh (27 June 2009). "Emergency: The Darkest Period in Indian Democracy". http://theviewspaper.net/emergency-the-darkest-period-in-indian-democracy/.

- Beyond the Last Blue Mountain - A Life of J.R.D. Tata by R. M. Lala.

- Nandini Satpathy (in Oriya) by Ashish Ranjan Mohapatra.

- "New book flays Indira Gandhi's decision to impose Emergency". IBN Live News. 30 May 2011. http://ibnlive.in.com/generalnewsfeed/news/new-book-flays-indira-gandhis-decision-to-impose-emergency/706495.html.

- O. P. Mathur. Indira Gandhi and the emergency as viewed in the Indian novel. Sarup & Sons. 2004. ISBN:978-81-7625-461-8.

- Hassan, Nigeenah; Sharma, Mukesh (2017). "India Under Emergency: Rich Like us Nayantara Sahgal". International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology 2,6. https://ijisrt.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/India-Under-Emergency-Rich-Like-us-Nayantara-Sahgal.pdf.

- Joseph Bendaña. "Rushdie Talk Recasts Role of Public and Private in Politics and Literature". Watson Institute, Brown University. 17 February 2010. http://watsoninstitute.org/news_detail.cfm?id=1291

- Nixon, Rob (1992). London calling : V.S. Naipaul, Postcolonial Mandarin. New York u.a.: Oxford Univ. Press. p. 73. ISBN 9780195067170. https://archive.org/details/londoncalling00robn. "India: A Wounded Civilization Naipaul emergency."

- "Delhi Calm". https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/8559030-delhi-calm.

- Gulzar; Nihalani, Govind; Chatterjee, Saibal (2003). Encyclopaedia of Hindi Cinema. New Delhi, Mumbai: Encyclopædia Britannica (India), Popular Prakashan. p. 425. ISBN 81-7991-066-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=8y8vN9A14nkC.

- Farzand Ahmed, "1978 – Kissa Kursi Ka: Celluloid chutzpah". Cover Story, India Today (24 December 2009) http://indiatoday.intoday.in/story/1978-+Kissa+Kursi+Ka:+Celluloid+chutzpah/1/76362.html