| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Camila Xu | -- | 1108 | 2022-11-14 01:43:00 |

Video Upload Options

In game theory, a focal point (or Schelling point) is a solution that people tend to choose by default in the absence of communication. The concept was introduced by the American economist Thomas Schelling in his book The Strategy of Conflict (1960). Schelling states that "(p)eople can often concert their intentions or expectations with others if each knows that the other is trying to do the same" in a cooperative situation (at page 57), so their action would converge on a focal point which has some kind of prominence compared with the environment. However, the conspicuousness of the focal point depends on time, place and people themselves. It may not be a definite solution.

1. Existence

The existence of the focal point is first demonstrated by Schelling with a series of questions. The most famous one is the New York City question: if you are to meet a stranger in New York City, but you cannot communicate with the person, then when and where will you choose to meet? This is a coordination game, where any place and time in the city could be an equilibrium solution. Schelling asked a group of students this question, and found the most common answer was "noon at (the information booth at) Grand Central Terminal". There is nothing that makes Grand Central Terminal a location with a higher payoff (you could just as easily meet someone at a bar or the public library reading room), but its tradition as a meeting place raises its salience and therefore makes it a natural "focal point".[1] Later, Schelling's informal experiments have been replicated under controlled conditions with monetary incentives by Judith Mehta.[2]

2. Theories

Although the concept of a focal point has been widely accepted in game theory, it is still unclear how a focal point forms. The researchers have proposed theories from two aspects.

2.1. The level-n Theory

Stahl and Wilson argue that a focal point is formed because players would try to predict how other players act. They model the level of "rational expectation" players by their ability to

- form priors (models) about the behavior of other players;

- choose the best responses given these priors.

A level-0 player will choose actions regardless of the actions of other players. A level-1 player believes that all other players are level-0 types. A level-n player estimates that all other players are level-0, 1, 2, ..., n-1 types. Based on experimental data, most of the players only use one model to predict the behavior of all the other players. Although the hierarchy of types could be indefinite, the benefits of higher levels would decrease substantially while incurring a much greater cost.[3] Because of the limit of players' expectation level and players' priors, it is possible to reach an equilibrium in games without communication.

The cognitive hierarchy theory

The cognitive hierarchy (CH) theory is a derivation of level-n theory. A level-n player from CH model would assume that the numbers level-0, 1, 2, ..., n-1 players follow a normalized Poisson distribution. [4] This model works well in multi-player games where the players need to estimate a number in a given range, such as the Keynesian beauty contest.

2.2. The Team Reasoning

Bacharach argued that people could find a focal point because they act as members of a team instead of individuals in a cooperative game.[5] With the identity changed, the player follows the prescription of an imaginary group leader to maximize the group interest.

3. Examples

3.1. Schelling's Questions

Here is a subset of the questions raised by Schelling to prove the existence of a focal point. [1]

- Head-tail game: Name "heads" or "tails". If the two players name the same, they win an award, otherwise, they get nothing.

- Letter order game: Give an order to letters A, B, and C. If the three players give the same order, they win an award, otherwise they get nothing.

- Split money game: Two players share $100. They first write down their individual claims on a sheet of paper. If their claims add to $100 or less, both of them will get exactly what they claimed, but if the sum is higher than $100 they get nothing.

The results of the informal experiments are

- For the two players, A and B, in head-tail game. 16 out of 22 A and 15 out of 22 B chose "heads".

- For the three players, A, B, and C, in letter order game. 9 out of 12 A, 10 out of 12 B, and 14 out of 16 C wrote "ABC".

- For the players to claim part of the $100. 36 out of 40 chose $50. 2 of the remainder chose $49 and $49.99.

These games suggest that focal points have some saliency. These characteristics make them preferable choices to people. Furthermore, people would assume each other has also noticed the saliency and make the same decision.[2]

3.2. In Coordination Game

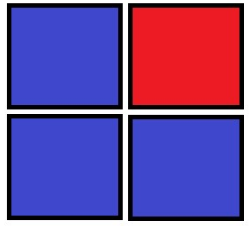

In a simple example, two people unable to communicate with each other are each shown a panel of four squares and asked to select one; if and only if they both select the same one, they will each receive a prize. Three of the squares are blue and one is red. Assuming they each know nothing about the other player, but that they each do want to win the prize, then they will, reasonably, both choose the red square.

The red square is not in a sense a better square; they could win by both choosing any square and in this sense, all squares are technically a Nash equilibrium. The red square is the "right" square to select only if a player can be sure that the other player has selected it, but by hypothesis neither can. However, it is the most salient and notable square, so—lacking any other one—most people will choose it, and this will in fact (often) work.

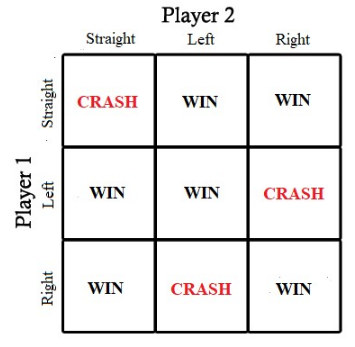

3.3. Collision Game

Focal points can also have real-life applications. For example, imagine two bicycles headed towards each other and in danger of crashing. Avoiding collision becomes a coordination game where each player's winning choice depends on the other player's choice. Each player, in this case, has the choice to go straight, swerve to the left or swerve to the right. Both players want to avoid crashing, but neither knows what the other will do.[6] In this case, the decision to swerve right can serve as a focal point which leads to the winning right-right outcome. It seems a natural focal point in places using right-hand traffic.

This idea of anti-coordination game is also apparent in the game of chicken, which involves two cars racing toward each other on a collision course and in which the driver who first decides to swerve is seen as a coward, while no driver swerving results in a fatal collision for both.

References

- Schelling, Thomas C. (1960). The strategy of conflict (First ed.). Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-84031-7.

- Mehta, Judith; Starmer, Chris; Sugden, Robert (1994). "The Nature of Salience: An Experimental Investigation of Pure Coordination Games". The American Economic Review 84 (3): 658–673. ISSN 0002-8282. http://www.worldcat.org/issn/0002-8282

- null

- Camerer, Colin F.; Ho, Teck-Hua; Chong, Juin-Kuan (1 August 2004). "A Cognitive Hierarchy Model of Games" (in en). The Quarterly Journal of Economics 119 (3): 861–898. doi:10.1162/0033553041502225. ISSN 0033-5533. https://academic.oup.com/qje/article-abstract/119/3/861/1938841.

- Bacharach, Michael (1 June 1999). "Interactive team reasoning: A contribution to the theory of co-operation". Research in Economics 53 (2): 117–147. doi:10.1006/reec.1999.0188. ISSN 1090-9443. https://dx.doi.org/10.1006%2Freec.1999.0188

- "Focal Points (or Schelling Points): How We Naturally Organize in Games of Coordination – Mind Your Decisions" (in en-US). https://mindyourdecisions.com/blog/2008/04/01/focal-points-or-schelling-points-how-we-naturally-organize-in-games-of-coordination/.