Video Upload Options

Dunkleosteus is an extinct genus of large armored, jawed fishes that existed during the Late Devonian period, about 382–358 million years ago. It consists of ten species, some of which are among the largest placoderms to have ever lived: D. terrelli, D. belgicus, D. denisoni, D. marsaisi, D. magnificus, D. missouriensis, D. newberryi, D. amblyodoratus, and D. raveri. The largest and most well known species is D. terrelli, which grew up to 8.79 m (28.8 ft) long and 4 t (4.4 short tons) in weight. Dunkleosteus could quickly open and close its jaw, like modern-day suction feeders, and had a bite force of 6,000 N (612 kgf; 1,349 lbf) at the tip and 7,400 N (755 kgf; 1,664 lbf) at the blade edge. Numerous fossils of the various species have been found in North America, Poland , Belgium, and Morocco.

1. Etymology

Dunkleosteus was named in 1956 to honour David Dunkle (1911–1982), former curator of vertebrate paleontology at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History. The genus name Dunkleosteus combines David Dunkle's surname with the Greek word ὀστέον (ostéon 'bone'), literally meaning 'Dunkle's-bone'. The type species D. terrelli was originally described in 1873 as a species of Dinichthys, its specific epithet chosen in honor of Jay Terrell, the fossil's discoverer.[1]

2. Taxonomy

Originally thought to be a member of the genus Dinichthys, Dunkleosteus was later recognized as belonging to its own genus in 1956. It was thought to be closely related to Dinichthys, and they were grouped together in the family Dinichthyidae. However, in the 2010 Carr & Hlavin phylogenetic study, Dunkleosteus and Dinichthys were found to belong to two separate clades. Carr & Hlavin resurrected the family Dunkleosteidae and placed Dunkleosteus, Eastmanosteus, and a few other genera from Dinichthyidae within it.[2] Dinichthyidae, in turn, is left a monospecific family.[3]

The cladogram below from the 2013 Zhu & Zhu study shows the placement of Dunkleosteus within Dunkleosteidae and Dinichthys within the separate clade Aspinothoracidi:[4]

Alternatively, the subsequent 2016 Zhu et al. study using a larger morphological dataset recovered Panxiosteidae well outside of Dunkleosteoidea, leaving the status of Dunkleosteidae as a clade grouping separate from Dunkleosteoidea in doubt, as shown in the cladogram below:[5]

2.1. Species

At least ten different species[2][6] of Dunkleosteus have been described so far.

The type species, D. terrelli, is the largest, best-known species of the genus, measuring in length. It has a rounded snout. D. terrelli's fossil remains are found in Upper Frasnian to Upper Famennian Late Devonian strata of the United States (Huron and Cleveland Shale of Ohio, the Conneaut of Pennsylvania, Chattanooga Shale of Tennessee, Lost Burro Formation, California, and possibly Ives breccia of Texas[6]) and Europe.

D. belgicus (?) is known from fragments described from the Famennian of Belgium. The median dorsal plate is characteristic of the genus, but, a plate that was described as a suborbital is anterolateral.[6]

D. denisoni is known from a small median dorsal plate, typical in appearance for Dunkleosteus, but much smaller than normal. It is comparable in skull structure to D. marsaisi.[6]

D. marsaisi refers to the Dunkleosteus fossils from the Lower Famennian Late Devonian strata of the Atlas Mountains in Morocco. It differs in size, the known skulls averaging a length of and in form to D. terrelli. In D. marsaisi, the snout is narrower, and a postpineal fenestra may be present. Many researchers and authorities consider it a synonym of D. terrelli.[7] H. Schultze regards D. marsaisi as a member of Eastmanosteus.[6][8]

D. magnificus is a large placoderm from the Frasnian Rhinestreet Shale of New York. It was originally described as Dinichthys magnificus by Hussakof and Bryant in 1919, then as " Dinichthys mirabilis" by Heintz in 1932. Dunkle and Lane moved it to Dunkleosteus in 1971.[6]

D. missouriensis is known from fragments from Frasnian Missouri. Dunkle and Lane regard them as being very similar to D. terrelli.[6]

D. newberryi is known primarily from a long infragnathal with a prominent anterior cusp, found in the Frasnian portion of the Genesee Group of New York, and originally described as Dinichthys newberryi.[6]

D. amblyodoratus is known from some fragmentary remains from Late Devonian strata of Kettle Point, Canada. The species name means 'blunt spear' and refers to the way the nuchal and paranuchal plates in the back of the head form the shape of a blunted spearhead. Although it is known only from fragments, it is estimated to have been about long in life.[2]

D. raveri is a small species, possibly 1 meter long, known from an uncrushed skull roof found in a carbonate concretion from near the bottom of the Huron Shale, of the Famennian Ohio Shale strata. Besides its small size, it had comparatively large eyes. Because D. raveri was found in the strata directly below the strata where the remains of D. terrelli are found, D. raveri may have given rise to D. terrelli. The species name commemorates Clarence Raver of Wakeman, Ohio, who discovered the concretion where the holotype was found.[2]

3. Description

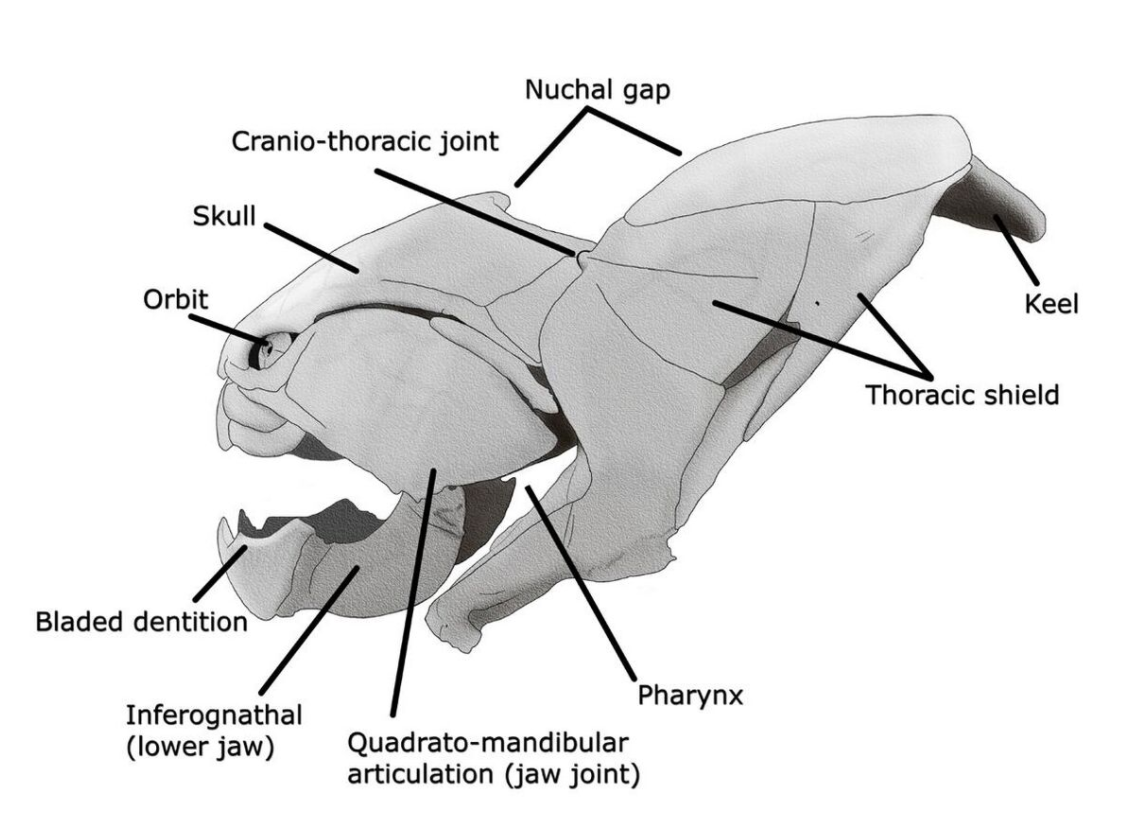

The largest species, D. terrelli, is estimated to have grown up to in length and in weight, making it one of the largest placoderms to have existed.[9][10][11][12][13] Like other placoderms, Dunkleosteus had a two-part bony, armoured exterior, which may have made it a relatively slow but powerful swimmer. Instead of teeth, Dunkleosteus possessed two pairs of sharp bony plates which formed a beak-like structure.[10] Dunkleosteus, together with most other placoderms, may have also been among the first vertebrates to internalize egg fertilization, as seen in some modern sharks.[14] Some other placoderms have been found with evidence that they may have been viviparous, including what appears to have been an umbilical cord.

Mainly the armored frontal sections of specimens have been fossilized, and consequently, the appearance of the other portions of the fish is mostly unknown.[15] In fact, only about 5% of Dunkleosteus specimens have more than a quarter of their skeleton preserved.[16] Because of this, many reconstructions of the hindquarters are often based on fossils of smaller arthrodires, such as Coccosteus, which have preserved hind sections. However, an exceptionally preserved specimen of D. terrelli preserves ceratotrichia in a pectoral fin, implying that the fin morphology of placoderms was much more variable than previously thought, and was heavily influenced by locomotory requirements. This knowledge, coupled with the knowledge that fish morphology is more heavily influenced by feeding niche than phylogeny, allowed a 2017 study to infer the body shape of D. terrelli. This new reconstruction gives D. terrelli a much more shark-like profile, including a strong anterior lobe on its tail, in contrast to reconstructions based on other placoderms.[12]

The largest collection of Dunkleosteus fossils in the world is housed at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History,[17] with smaller collections (in descending order of size) held at the American Museum of Natural History,[18] Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History,[19] Yale Peabody Museum,[20] the Natural History Museum in London, and the Cincinnati Museum Center. Specimens of Dunkleosteus are on display in many museums throughout the world (see table below), most of which are casts of CMNH 5768, the largest well-preserved individual of D. terrelli,[12] the original of which is on display in the Cleveland Museum of Natural History.

| Museum | City | State/Province | Country | Dunkleosteus Specimen |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cleveland Museum of Natural History | Cleveland | Ohio | United States | CMNH 5768 (original), also has smaller juvenile individual on display (CMNH 7424). Two other mounted individuals currently off display (CMNH 6090 and CMNH 7054), and a fifth that was once mounted but has since been disassembled (CMNH 6194). |

| American Museum of Natural History | New York City | New York | U.S. | AMNH 7301 (at least in part, may be a composite)[21] |

| Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History | Washington D.C. | Washington D.C. | U.S. | USNM V 21314[19] |

| The Field Museum | Chicago | Illinois | U.S. | Cast of CMNH 5768 |

| Carnegie Museum | Pittsburgh | Pennsylvania | U.S. | Cast of CMNH 5768 |

| University of Michigan Museum of Natural History | Ann Arbor | Michigan | U.S. | Cast of CMNH 5768 |

| Royal Ontario Museum | Toronto | Ontario | Canada | Cast of CMNH 5768 |

| Royal Tyrell Museum | Drumheller | Alberta | Canada | Cast of CMNH 5768 |

| University of Alberta Museum of Paleontology | Edmonton | Alberta | Canada | Cast of CMNH 5768 |

| Denver Museum of Nature and Science | Denver | Colorado | U.S. | Cast of CMNH 5768 |

| Burpee Museum of Natural History | Rockford | Illinois | U.S. | Cast of CMNH 5768[22] |

| Museum of Comparative Zoology | Harvard | Massachusetts | U.S. | Had a real mounted specimen of Dunkleosteus terrelli at one point, no longer clear if specimen is still on display.[23] |

| Sam Noble Oklahoma Museum of Natural History | Oklahoma City | Oklahoma | U.S. | Cast of CMNH 5768 |

| Museum of the Earth | Ithaca | New York | U.S. | Cast of CMNH 5768 |

| Great Lakes Aquarium | Duluth | Minnesota | U.S. | Cast of CMNH 5768 |

| Indiana State Museum | Indianapolis | Indiana | U.S. | Cast of CMNH 5768 |

| Orton Geological Museum | Columbus | Ohio | U.S. | Cast of CMNH 5768[24] |

| Cleveland Metroparks, Rocky River Nature Center | Rocky River | Ohio | U.S. | Cast of CMNH 5768 |

| Cincinnati Museum Center | Cincinnati | Ohio | U.S. | Cast of CMNH 5768 |

| Indiana State Museum | Indianapolis | Indiana | U.S. | Cast of CMNH 5768 |

| Pennsylvania State Museum | Harrisburg | Pennsylvania | U.S. | Cast of CMNH 5768[25] |

| Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle | Paris | Paris | France | Cast of CMNH 5768[26] |

| Naturmuseum Senckenberg | Frankfurt | Hesse | Germany | Cast of CMNH 5768 |

| Vienna Natural History Museum | Vienna | Vienna | Austria | Cast of CMNH 5768[27] |

| National Museum of Nature and Science | Tokyo | Kantō | Japan | Cast of CMNH 5768 |

| Queensland Museum | South Brisbane | Queensland | Australia | Cast of CMNH 5768[28] |

| Buffalo Museum of Science | Buffalo | New York | U.S. | BMS E 2381 Specimen of "Dinichthys" magnificus, which may or may not pertain to Dunkleosteus. Additional isolated material of D. terrelli on display. |

| Wyoming Dinosaur Center | Thermopolis | Wyoming | U.S. | Dunkleosteus maraisai, purportedly original specimen |

| Virginia Museum of Natural History | Charleston | South Carolina | U.S. | Cast of Dunkleosteus maraisai |

| Mace Brown Museum of Natural History | Charleston | South Carolina | U.S. | Cast of Dunkleosteus maraisai |

3.1. Diet

Dunkleosteus terrelli possessed a four-bar linkage mechanism for jaw opening that incorporated connections between the skull, the thoracic shield, the lower jaw and the jaw muscles joined together by movable joints.[9][10] This mechanism allowed D. terrelli to both achieve a high speed of jaw opening, opening their jaws in 20 milliseconds and completing the whole process in 50–60 milliseconds (comparable to modern fishes that use suction feeding to assist in prey capture;[9]) and producing high bite forces when closing the jaw, estimated at at the tip and at the blade edge in the largest individuals.[10] The pressures generated in those regions were high enough to puncture or cut through cuticle or dermal armor[9] suggesting that D. terrelli was adapted to prey on free-swimming, armored prey such as ammonites and other placoderms.[10] Fossils of Dunkleosteus are frequently found with boluses of fish bones, semidigested and partially eaten remains of other fish.[29] As a result, the fossil record indicates it may have routinely regurgitated prey bones rather than digest them. Mature individuals probably inhabited deep sea locations, like other Placoderms, living in shallow waters during adolescence.[30]

3.2. Juveniles

Morphological studies on the lower jaws of juveniles of D. terrelli reveal they were proportionally as robust as those of adults, indicating they already could produce high bite forces and likely were able to shear into resistant prey tissue similar to adults, albeit on a smaller scale. This pattern is in direct contrast to the condition common in tetrapods in which the jaws of juveniles are more gracile than in adults.[31]

References

- "Dunkleosteus terrelli: Fierce prehistoric predator" page at Cleveland Museum of Natural History. https://www.cmnh.org/dunk

- Carr R. K., Hlavin V. J. (2010). "Two new species of Dunkleosteus Lehman, 1956, from the Ohio Shale Formation (USA, Famennian) and the Kettle Point Formation (Canada, Upper Devonian), and a cladistic analysis of the Eubrachythoraci (Placodermi, Arthrodira)". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 159 (1): 195–222. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2009.00578.x. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2Fj.1096-3642.2009.00578.x

- Carr, Robert K.; William J. Hlavin (September 2, 1995). "Dinichthyidae (Placodermi):A paleontological fiction?". Geobios 28: 85–87. doi:10.1016/S0016-6995(95)80092-1. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2FS0016-6995%2895%2980092-1

- You-An Zhu; Min Zhu (2013). "A redescription of Kiangyousteus yohii (Arthrodira: Eubrachythoraci) from the Middle Devonian of China, with remarks on the systematics of the Eubrachythoraci". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 169 (4): 798–819. doi:10.1111/zoj12089. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2Fzoj12089

- Zhu, You-An; Zhu, Min; Wang, Jun-Qing (April 1, 2016). "Redescription of Yinostius major (Arthrodira: Heterostiidae) from the Lower Devonian of China, and the interrelationships of Brachythoraci". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 176 (4): 806–834. doi:10.1111/zoj.12356. ISSN 0024-4082. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2Fzoj.12356

- Denison, Robert (1978). "Placodermi". Handbook of Paleoichthyology. 2. Stuttgart New York: Gustav Fischer Verlag. pp. 128. ISBN 978-0-89574-027-4.

- Murray, A.M. (2000). "The Palaeozoic, Mesozoic and Early Cenozoic fishes of Africa". Fish and Fisheries 1 (2): 111–145. doi:10.1046/j.1467-2979.2000.00015.x. https://dx.doi.org/10.1046%2Fj.1467-2979.2000.00015.x

- Schultz, H (1973). "Large Upper Devonian arthrodires from Iran". Fieldiana Geology 23: 53–78. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.5270. https://dx.doi.org/10.5962%2Fbhl.title.5270

- Anderson, P.S.L.; Westneat, M. (2007). "Feeding mechanics and bite force modelling of the skull of Dunkleosteus terrelli, an ancient apex predator". Biology Letters 3 (1): 76–79. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2006.0569. PMID 17443970.

- Anderson, P.S.L.; Westneat, M. (2009). "A biomechanical model of feeding kinematics for Dunkleosteus terrelli (Arthrodira, Placodermi)". Paleobiology 35 (2): 251–269. doi:10.1666/08011.1. Retrieved October 29, 2017.

- Carr, Robert K. (2010). "Paleoecology of Dunkleosteus terrelli (Placodermi: Arthrodira).". Kirtlandia 57. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/235924093.

- Ferrón, Humberto G.; Martínez-Pérez, Carlos; Botella, Héctor (December 6, 2017). "Ecomorphological inferences in early vertebrates: reconstructing Dunkleosteus terrelli (Arthrodira, Placodermi) caudal fin from palaeoecological data" (in en). PeerJ 5: e4081. doi:10.7717/peerj.4081. ISSN 2167-8359. PMID 29230354. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=5723140

- "Ancient Predator Had Strongest Bite Of Any Fish, Rivaling Bite Of Large Alligators And T. Rex" (in en). ScienceDaily. November 29, 2006. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2006/11/061129094125.htm.

- Ahlberg, Per; Trinajstic, Kate; Johanson, Zerina; Long, John (2009). "Pelvic claspers confirm chondrichthyan-like internal fertilization in arthrodires". Nature 460 (7257): 888–889. doi:10.1038/nature08176. PMID 19597477. Bibcode: 2009Natur.460..888A. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038%2Fnature08176

- Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter exited with status 1. REDIRECT Template:Dead YouTube links Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter exited with status 1.

- Carr, R, & G.L. Jackson. 2008. The Vertebrates fauna of the Cleveland member (Famennian) of the Ohio Shale. Society of Vertebrates Paleontology. 1–17.

- "Dunkleosteus terrelli: Fierce prehistoric predator". https://www.cmnh.org/dunk.

- "Dunkleosteus". https://www.amnh.org/exhibitions/permanent/vertebrate-origins/dunkleosteus.

- "Collections Catalog of the Department of Paleobiology of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History". Smithsonian Institute. https://collections.nmnh.si.edu/search/paleo/.

- "Collections Database of the Yale Peabody Museum". Yale Peabody Museum. https://collections.peabody.yale.edu/search/Search/Results?sort=relevance&join=AND&lookfor0%5B%5D=dunkleosteus&type0%5B%5D=AllFields&lookfor0%5B%5D=&type0%5B%5D=AllFields&lookfor0%5B%5D=&type0%5B%5D=AllFields&bool0%5B%5D=AND&lookfor1%5B%5D=VP&type1%5B%5D=CatalogNumber&lookfor1%5B%5D=VPPU&type1%5B%5D=CatalogNumber&bool1%5B%5D=OR&filter%5B%5D=%7Ecollection%3A%22Vertebrate+Paleontology%22&limit=5&daterange%5B%5D=collecting_year_first&collecting_year_firstfrom=&collecting_year_firstto=.

- Dean, Bashford (1909). "A Mounted Specimen of Dinichthys terrelli". Memoirs of the American Museum of Natural History 9 (5): 268-271. https://digitallibrary.amnh.org/handle/2246/57.

- ""Photo of Burpee Museum Dunkleosteus"". https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Burpee_-_Dunkleosteus_terrelli.JPG.

- Stetson, H. (1930). "Notes on the structure of Dinichthys and Macropetalichthys". Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology 71: 19-39.

- ""Photo of Orton Geological Museum Dunkleosteus"". https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dunkleosteus_terrelli_(fossil_fish)_(Cleveland_Shale_Member,_Ohio_Shale,_Upper_Devonian;_Rocky_River_Valley,_Cleveland,_Ohio,_USA)_6_(33974377672).jpg.

- "Dunkleosteus". September 1, 2017. https://statemuseumpa.org/dunkleosteus-websized/.

- ""Photo of MNHN Dunkleosteus"". https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dunkleosteus_terrelli_343.JPG.

- ""Photo of Vienna Museum Dunkleosteus"". https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dunkleosteus_(15677042802).jpg.

- "File:Dunkleosteus skull QM email.jpg". August 21, 2006. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dunkleosteus_skull_QM_email.jpg.

- "Dunkleosteus Placodermi Devonian Armored Fish from Morocco". Fossil Archives. The Virtual Fossil Museum. http://www.fossilmuseum.net/Fossil_Galleries/Fish_Devonian/Dunkleosteous/Dunkleosteus.htm.

- "UWL Website". http://bioweb.uwlax.edu/bio203/f2013/peters_sadi/habitat.htm.

- Snively, E.; Anderson, P.S.L.; Ryan, M.J. (2009). "Functional and ontogenetic implications of bite stress in arthrodire placoderms". Kirtlandia 57.