| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Roberto Comparelli | + 3200 word(s) | 3200 | 2020-12-02 07:55:12 | | | |

| 2 | Vivi Li | + 3 word(s) | 3203 | 2020-12-08 05:29:43 | | |

Video Upload Options

Pathogenic microorganisms can spread throughout the world population, as the current COVID-19 pandemic has dramatically demonstrated. In this scenario, a protection against pathogens and other microorganisms can come from the use of photoactive materials as antimicrobial agents able to hinder, or at least limit, their spreading by means of photocatalytically assisted processes activated by light—possibly sunlight—promoting the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that can kill microorganisms in different matrices such as water or different surfaces without affecting human health. Here, we focus the attention on TiO2 nanoparticle-based antimicrobial materials, intending to provide an overview of the most promising synthetic techniques, toward possible large-scale production, critically review the capability of such materials to promote pathogen (i.e., bacteria, virus, and fungi) inactivation, and, finally, take a look at selected technological applications.

1. Introduction

Over the last decades, titanium dioxide (TiO2) has been extensively investigated for its physical-chemical properties, that, combined with its high stability, low cost, and safety for the environment and humans, have resulted in a range of environmental and energy applications.

When TiO2 is obtained at nanoscale, many relevant properties of this semiconductor are enhanced, due to the increased surface area, which results from the high surface-to-volume ratio, the excellent surface morphology, and the band edge modulation, that, overall, turn into a control on the photocatalytic behavior and performance of the nanostructured materials [1][2][3].

Upon illumination, TiO2 nanoparticles (NPs) convert incoming photons into excitons, or electron/hole pairs, which can migrate to the surface and participate in redox reactions and generate reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as hydroxyl radicals (OH·) and superoxide(O2−) [3][4].

Indeed, the photocatalytic behavior of TiO2 NPs has been widely exploited for removal of water and air contaminants and self-cleaning surfaces [1][2][3][4]. Currently, increasing concerns regarding the COVID-19 pandemic are drawing the attention of researchers and general public more and more to photocatalytic antimicrobial and antiviral treatments with the purpose of hindering virus spreading, by using light (possibly solar light) activated systems.

TiO2 NPs are among the most studied materials in the area of photocatalytic antimicrobial applications, having demonstrated a great potential for the disinfection/inactivation of harmful pathogens, including bacteria, viruses, and fungi [5]. However, aside from the superior advantage of TiO2 nanostructured materials, some drawbacks have been identified, i.e., high recombination rate of the photogenerated species and limited solar light sensitivity, therefore various modifications have been developed to enhance the photocatalytic efficiency [3][4].

Upon photoactivation of TiO2 NPs, the biocidal action is a result of the modulation of charge carriers, electrons, and holes at the surface of the material, resulting in powerful and long-lasting capabilities [1], since the process does not rely on the release of metal ions, and hence the material consumption, as it happens in the case of Ag-based antimicrobial material. Moreover, TiO2 NPs-based systems have a substantial advantage due to their non-contact biocidal action. Finally, since any possible release into the environment of potentially toxic NPs—with unpredictable effects on human health—from the material or device for the final application must be prevented, the TiO2-based structures are required to be suited for immobilization onto substrate and/or incorporation in matrices. In this regard, this class of materials could be considered reasonably environmentally friendly.

The antimicrobial activity of TiO2 NPs is primarily attributed to the photocatalytic generation, under band-gap irradiation, of ROS with high oxidative potentials. However, other possible factors may be considered to explain their biocidal effect, such as free metal ions formation or synergistic effects deriving from the combination of TiO2 NPs with other materials and compounds in nanocomposite systems [1][2][5].

2. Technological Applications of Antimicrobial TiO2-Based Nanostructured Materials

2.1. Environmental Applications

2.1.1. TiO2-Based Nanostructured Materials for Water Disinfection

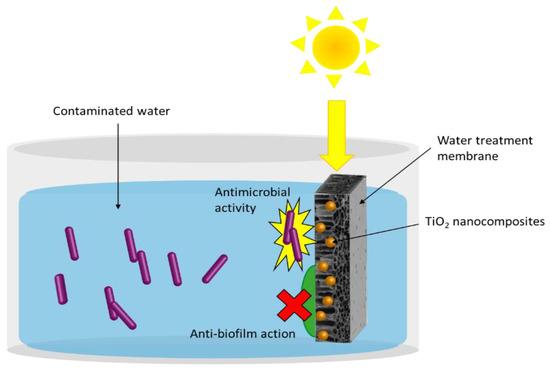

TiO2 based nanocomposites are well known and extensively used materials in water treatment technologies [3][4][6]. Indeed they are able, due to their photocatalytic activity, to degrade organic pollutants such as dyes, [7] pesticides [8], pharmaceuticals [3][9], and personal care products [10], that pose a great danger for human and aquatic life. Moreover, their antimicrobial properties are effective against waterborne pathogens such as bacteria, viruses, and fungi that originate from the urban microbiome and tend to be released and accumulated in sewage and urban runoff. The mechanism is summarized in Figure 1 and will be explained in the following. Waterborne diseases derive often from bacteria such as E. coli, Legionella pneumophila, Mycobacterium avium, S. flexneri, L. monocytogenes, V. parahaemolyticus and, to a lesser extent, from viruses, that are typically present at lower concentration. Every year, waterborne infections cause nearly 200 million deaths worldwide, mainly localized in low income countries [11]. One of the most critical classes of bacteria in wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) is antibiotic resistant bacteria (ARB), which derive from the extensive use and abuse of antibiotics. WWTPs offer an ideal environment for ARB proliferation and, under these conditions, the antibiotic resistance genes (ARG) that induce the resistance in the bacterial population, can spread easily and quickly. Therefore, as the use of common antibiotics becomes ineffective, it is fundamental to develop alternative strategies to treat microbial infections and to promptly take action against the spreading of ARB in water as well as in the air [12]. The present section will focus on TiO2-based nanomaterials as an excellent alternative to conventional methods for water disinfection. In addition, nanomaterials applied to counteract the biofouling will be reviewed, as it is another great problem affecting water treatment plants as well as materials in contact with water, including distribution pipes and filtration membranes [13].

Figure 1. General scheme of TiO2 NPs-based nanocomposite application for water disinfection, that highlights the ability to prevent biofilm formation at the surface of the substrate, such as a membrane, and the antibacterial activity against water pathogens driven by photocatalysis.

TiO2 NPs-based nanocomposites for water disinfection are often investigated as colloidal suspensions, since, under these conditions, the whole NPs surface is available, exposing all the active catalytic sites to the aqueous environment dispersing the pathogens. However, while suspended NPs are typically found to display a higher photocatalytic activity in comparison with NPs immobilized on a substrate [14], the dispersed NPs present technological problems, as they need to be recovered to prevent them from becoming a source of pollution in the environment.

2.1.2. Immobilization of Nanocomposites on Membranes or Recoverable Supports

The immobilization of photocatalytic TiO2 NPs and their nanocomposites onto a suitable substrate is essential to accomplish technologically feasible applications. As mentioned above, a robust and durable immobilization of NPs onto appropriate support is fundamental, not only for enabling the nanosized photocatalyst recovery, but also to prevent the accidental release of NPs in the environment, that, becoming themselves a possible contaminant, may become harmful [4]. Here, some of the most original proposed solutions for the deposition and immobilization of TiO2 NPs-based nanomaterials specifically designed for photocatalytic microorganism inactivation are summarized.

Photocatalytic membrane reactors (PMRs) combine the membrane technology with the advantages of photocatalysis assisted reactions. Two main configurations are reported in the literature: PMRs with the photocatalyst immobilized on the membrane or incorporated therein, and PMRs based on the photocatalyst dispersed in a colloidal suspension. In both cases the photocatalyst is confined in the reaction environment. However, the former configuration allows an effective recovery and reuse of the catalyst, thanks to its stable immobilization, while the recovery is more complicated in the latter case, although the whole NPs surface can be more effectively exploited for adsorption and catalysis [15]. Among the possible photocatalysts for PMR fabrication, TiO2 NPs and TiO2 NPs-based nanocomposites have been the most investigated [16]. Cheng et al. fabricated a PMR based on the combination of a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane and a suspension of TiO2 P25 in tap water and studied the biocide effect for virus removal, using phage f2 as a model. The effect of the amount of humic acid (HA) in the water dispersion on the efficiency of the system was also investigated. Moreover, HA was found to compete with phage f2 at the adsorption sites on TiO2 NPs surface, and the UV light absorbed by HA overall led to a reduction of biocide activity at high HA concentration [17]. A PMR based on a microfiltration hollow polyethylene (PE) fiber membrane coupled with a suspension of TiO2 P25 was investigated for the reduction in bacterial population of secondary effluent water sample, that was assessed, down to 2 log, when a 1g/L TiO2 NPs suspension was used [18]. Another typical and efficient approach for nanocatalyst immobilization, able to preserve their activity, relies on their immobilization onto fibers that, possessing a high surface, allow optimal interaction between the target substrate dispersed in water and the photocatalyst. Amarjargal et al. functionalized the surface of electrospun polyurethane (PU) fibers with Ag-TiO2 NPs by simply dipping the fiber in hot colloidal photocatalyst dispersion for 4 h and 12 h. After 3 h UV irradiation (320–500nm), a 6-log cycles reduction of E. coli population was found for the sample obtained after 4 h immersion and a 5-log cycles reduction for that immersed for 12 h. Interestingly, only 2-log cycles reduction was detected after exposure to UV, in absence of Ag-TiO2 and no reduction was observed upon exposure of the nanocomposite to ambient light [19]. The antibacterial activity of electrospun Ag-TiO2 nanofibers was tested against E. coli. The study demonstrated that, under the investigated experimental conditions: (i) no biocidal activity was obtained upon exposure to light (solar simulator) of the bare fiber, nor in the dark for TiO2/Ag fibers and P25-coated fibers, (ii) fibers functionalized with the synthesized TiO2 performed better, in terms of photocatalytic antibacterial activity, than fibers coated with TiO2 P25, and (iii) the antibacterial activity in presence of Ag NPs was found higher in the dark than under light irradiation [20]. A TiO2/Polyamide 6 (PA-6) electrospun fiber was tested by Daels et al. for the removal of St. aureus and HA from a secondary effluent sample. HA reduction of 83% after 2 h irradiation with simulated solar light (300 W Osram Ultra-Vitalux lamp) with an intensity of about 5 mW/cm2 and 99.99% bacteria reduction after 6h UV irradiation was detected. The same fibers, tested in a filtration process (flow rate 11 m3/(m2h)) in a photocatalytic experiment performed under UV irradiation achieved 37% HA reduction and 76% St. aureus inactivation [21]. Zheng et al. electrospun Cu-TiO2 nanofibers and tested the biocide activity under visible light against f2 phage and the system formed by f2 phage and E. coli as its host, and reported a photocatalytic inactivation of E. coli higher than that of f2 phage. Remarkably, the E. coli inactivation did not seem affected by the presence of f2 phage, while the inactivation of the phage f2 in the bacteria host system was lower than that found in absence of E. coli. Such a result was explained by considering that E. coli can behave as a ROS scavenger, probably due to its membrane structure, as discussed above, thus reducing amount of ROS effective for f2 inactivation, thus somehow preventing its inactivation [22].

2.1.3. Anti-Biofouling Membranes for Water Treatment

The biofouling process is defined as the accumulation of microorganisms on a surface, and is realized in four steps: (i) organic matters are adsorbed on the surface, (ii) microorganisms adsorb and adhere to the surface, and (iii) start to grow and reproduce on the surface, and finally (iv) extracellular polymers are secreted and mutual adhesion among the clonal cells takes place [23]. These processes ultimately result in the formation of a biofilm, namely an assembly of microbial cells, irreversibly bound to a surface and embedded in a matrix of polysaccharide material [24]. When biofouling takes place at the surface of a membrane, its flux is limited, thus interfering with rejection and reducing the lifetime of the membrane itself, with the consequent drawbacks. In order to prevent biofilm formation, two main strategies can be employed. The first relies on the ability to enhance the hydrophilicity of the membrane, which reduces the affinity of the organic matter, and enhances its affinity with water, that can, thus, form a thin layer on the membrane surface, finally hampering the microorganisms’ adhesion. The second route is based on the incorporation of antibacterial agents into the membrane, such as TiO2-based nanomaterials [25]. TiO2-based nanocomposites are greatly suggested for this application since they display antibacterial properties and, concomitantly, convey, as a function of their chemical nature, hydrophilicity to the host membrane [26]. The combination of the intrinsic antibacterial properties with the photocatalytic properties of TiO2 NPs-based nanocomposites offers multiple advantages for hindering the biofouling. As an example, Kim et al. deposited TiO2 NPs on a polyamide thin film composite (TFC) membrane and tested their anti-biofouling properties, along with the antibacterial activity against E. coli. The water flux was measured for three days, for pristine and TiO2 NPs-modified membrane, and with and without UV-light irradiation. After pipetting E. coli dispersion onto the membranes and incubating at 37 °C, a fast and significant reduction of the flux, a clear indication of the occurrence of a higher fouling, was observed for the membranes not exposed to UV, while a slow and low reduction of the flux was found for TiO2-modified membranes, especially upon UV irradiation, finally demonstrating how the anti-biofouling activity is tightly connected to antibacterial behavior of UV-active TiO2 photocatalysts [27].

2.2. TiO2 NPs-Based Nanocomposite against Biofouling on Building Materials

In the construction field, nanostructured TiO2 is commonly employed to degrade organic pollutants in the air or to protect the building materials from soot, due to its photocatalytic and hydrophobic properties. The biocide activity of TiO2 can also be exploited to reduce the formation of biofilms formed on the surface of buildings [28]. Indeed, biofouling causes, not only aesthetic and structural degradation of construction materials and surfaces, but also bacteria and fungi proliferation that may pose a great health concern [29]. The application of photocatalytic TiO2 NPs as a biocidal agent has considerable relevance, especially for locations strongly sensitive to biological safety, such as medical facilities and food industries, where usually ceramic tiles are used to coat walls and floor. The photocatalytic activity of TiO2 nanomaterials was found to successfully reduce the bacterial proliferation and the fungi population (and, consequently, mycotoxins production) indoor when applied to surfaces, tiles, furniture etc. [30]. Dyshlyuk et al. tested suspensions of TiO2, ZnO, and SiO2 against microorganisms known for damaging construction materials, namely a bacterium (B. subtilis) and several common fungi (A. niger, Aspergillus terreus, Aureobasidium pullulans var. pullulans, Cladosporium cladosporioides, Penicillium ochrochloron, Trichoderma viride, and Paecilomyces variotii). They found TiO2 and SiO2 less active under sunlight than ZnO [31]. Sikora et al. fabricated core-shell nanocomposites of mesoporous silica (mSiO2, core) and TiO2 (shell) to be applied on cement mortars. The merging of the two nanomaterials in one nanocomposite was found to play the two roles of introducing in the building material a filler, mSiO2, able to improve its mechanical properties, and conveying, with TiO2, anti-biofouling and self-cleaning activity upon UV exposure. The mSiO2/TiO2 composite antibacterial activity was tested against E. coli and, after 2 h, a 67% and a 42% reduction were measured after exposure to UV light and at dark, respectively [32].

2.3. Photocatalytic TiO2 NPs-Based Nanocomposites for Biomaterials Disinfection

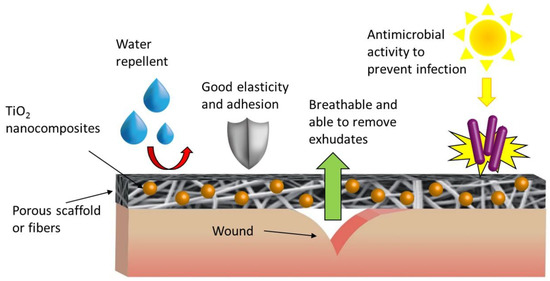

Antibacterial NPs find a wide range of applications in the field of biomaterials. Materials designed for wound dressing or for tissue engineering-related applications need to comply with several requirements as summarized in Figure 2, as they need to be biocompatible, non-allergenic, easily removable, and degradable after implantation.

Figure 2. General scheme of TiO2 NPs-based nanocomposite application for biomaterial-related applications highlighting the ability to repel water, to adhere to the skin following its movements, to remove exudates, to be permeable to air, and to prevent infections due to the antimicrobial activity driven by photocatalysis.

Antibacterial behavior is strongly desirable in this kind of material to prevent infections during wound recovery [33][34]. A great deal of work has been carried out in the development of biocompatible TiO2-NPs-based nanocomposites, with intrinsic antimicrobial activity, specifically designed for tissue engineering-related applications to be used in healthcare facilities [35][36][37][38][39][40].

2.4. TiO2 NPs-Based Nanocomposites Designed for Disinfection of Food Packaging and Processing Materials

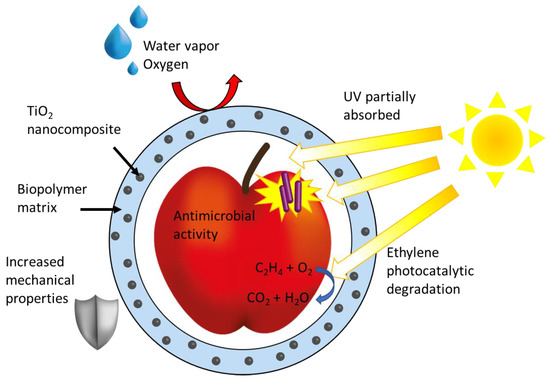

Food packaging materials containing TiO2 NPs-based nanocomposites have been thoroughly investigated materials for food contact-related applications and a steadily increasing number of technologies has been in development in the last years. This is in order to accomplish multiple purposes including improved mechanical, thermal, optical and antimicrobial properties, control of gas and moisture permeability, UV shielding, nutraceuticals release, and installing sensors for pathogens and harmful substances (Figure 3) [41][42][43]. Indeed, surfaces of food-processing plant components need to comply with the same requirements, as they are often in contact with food and the presence of microorganisms therein can easily lead to food contamination, causing transmission of diseases [17]. Indeed, the presence of antimicrobial substances in food packaging materials may inhibit growth of harmful microorganisms and pathogens on food, improving its safety and shelf life. NPs and nanocomposites can be integrated in food packaging materials as growth inhibitors, antimicrobial agents, or carriers [44], and are usually applied to the packaging of meat, fish, poultry, bread, cheese, fruits, and vegetables [45]. TiO2 NPs, aside from antibacterial properties, also possess unique characteristics that may prove particularly useful for such applications. For example, TiO2 shields UV light, a property that is generally exploited in the formulation of sunscreen lotions, and therefore may be an effective additive in packaging to preserve food from irradiation, and thus limit its deterioration [46][47]. Moreover, when TiO2 NPs are contained in a packaging material, upon UV exposure they can photocatalytically degrade the ethylene molecules produced during the ripening process, which are responsible for food degradation [48].

Figure 3. General scheme of TiO2 NPs-based nanocomposite application for food packaging highlighting the advantages of TiO2 in the coating as improved mechanical properties, water and oxygen repellence, UV shielding, and ethylene scavenger and antimicrobial activity.

In the last years, the choice of a polymer suitable and environmentally sustainable for food packaging has oriented towards biopolymers, which can be easily degraded and recycled, for a more ecological fingerprint in a field that has been, so far, heavily relying on petroleum-based polymers. Such biopolymers include poly hydroxybutyrates (PHB), polylactic acid (PLA), poly caprolactone (PCL), polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), poly butylene succinate, lipids (wax and free fatty acids), proteins (casein, whey, and gluten), polysaccharides (starch and cellulose derivatives, alginates, and chitosan) and their possible blends [49]. In particular, chitosan, a polysaccharide derived from chitin, is especially suited for food packaging, considering, as reported above, its biocompatibility, biodegradability, and antibacterial and antifungal behavior, along with good film forming properties [46][50].

Besides chitosan-based blends, many other polymers have been used recently to develop antimicrobial composite coatings containing TiO2 NPs for food packaging. Xie et al., for example, embedded TiO2 NPs into three different biodegradable polymers: cellulose acetate (CA), polycaprolactone (PCL), and PLA. A higher compatibility of TiO2 with CA and PLA was observed, along with improved film forming properties, resulting in uniform films. Moreover, the CA/TiO2-based films showed a high transparency, and good photocatalytic activity, as demonstrated by degradation of methylene blue upon irradiation with a UV-A light. The best antibacterial activity under the investigated experimental conditions, when compared to the other systems, was found against E. coli upon 2 h UV-A light irradiation with light intensity of 1.30 ± 0.15 mW/cm2, and was found to increase at higher TiO2 concentration, achieving a 1.69 log CFU/mL reduction. Very low reduction was, instead, observed, even at the highest TiO2 concentration, without irradiation [51]. Xie et al. thoroughly investigated the behavior of the best performing CA/TiO2 coatings when the bacteria were inoculated under the coating itself and—upon UV-A exposure—a higher TiO2 concentration was found to act as a screen, decreasing the intensity of the light reaching the inoculum and resulting in reduced antibacterial activity [52].

References

- Laxma Reddy, P.V.; Kavitha, B.; Kumar Reddy, P.A.; Kim, K.-H. TiO2-based photocatalytic disinfection of microbes in aqueous media: A review. Environ. Res. 2017, 154, 296–303.

- Li, Q.; Mahendra, S.; Lyon, D.Y.; Brunet, L.; Liga, M.V.; Li, D.; Alvarez, P.J.J. Antimicrobial nanomaterials for water disinfection and microbial control: Potential applications and implications. Water Res. 2008, 42, 4591–4602.

- Petronella, F.; Truppi, A.; Sibillano, T.; Giannini, C.; Striccoli, M.; Comparelli, R.; Curri, M.L. Multifunctional TiO2/FexOy/Ag based nanocrystalline heterostructures for photocatalytic degradation of a recalcitrant pollutant. Catal. Today 2017, 284, 100–106.

- Petronella, F.; Truppi, A.; Ingrosso, C.; Placido, T.; Striccoli, M.; Curri, M.L.; Agostiano, A.; Comparelli, R. Nanocomposite materials for photocatalytic degradation of pollutants. Catal. Today 2017, 281, 85–100.

- Khezerlou, A.; Alizadeh-Sani, M.; Azizi-Lalabadi, M.; Ehsani, A. Nanoparticles and their antimicrobial properties against pathogens including bacteria, fungi, parasites and viruses. Microb. Pathog. 2018, 123, 505–526.

- Abdelbasir, S.M.; Shalan, A.E. An overview of nanomaterials for industrial wastewater treatment. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2019, 36, 1209–1225.

- Akpan, U.G.; Hameed, B.H. Parameters affecting the photocatalytic degradation of dyes using TiO2-based photocatalysts: A review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 170, 520–529.

- Reddy, P.V.; Kim, K.H. A review of photochemical approaches for the treatment of a wide range of pesticides. J. Hazard. Mater. 2015, 285, 325–335.

- Truppi, A.; Petronella, F.; Placido, T.; Margiotta, V.; Lasorella, G.; Giotta, L.; Giannini, C.; Sibillano, T.; Murgolo, S.; Mascolo, G.; et al. Gram-scale synthesis of UV–vis light active plasmonic photocatalytic nanocomposite based on TiO2/Au nanorods for degradation of pollutants in water. Appl. Catal. B 2019, 243, 604–613.

- Tahir, M.B.; Ahmad, A.; Iqbal, T.; Ijaz, M.; Muhammad, S.; Siddeeg, S.M. Advances in photo-catalysis approach for the removal of toxic personal care product in aqueous environment. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020, 22, 6029–6052.

- JISR1702:2012. Fine Ceramics (Advanced Ceramics, Advanced Technical Ceramics)—Test Method For Antibacterial Activity of Photocatalytic Products under Photoirradiation and Efficacy; Japanese Standards Association, 2012.

- Zhang, G.; Li, W.; Chen, S.; Zhou, W.; Chen, J. Problems of conventional disinfection and new sterilization methods for antibiotic resistance control. Chemosphere 2020, 254, 126831.

- Mahendra, S.; Li, Q.L.; Lyon, D.Y.; Brunet, L.; Alvarez, P.J.J. Nanotechnology-Enabled Water Disinfection and Microbial Control: Merits and Limitations; William Andrew Inc.: Norwich, UK, 2009; pp. 157–166.

- Mascolo, G.; Comparelli, R.; Curri, M.L.; Lovecchio, G.; Lopez, A.; Agostiano, A. Photocatalytic degradation of methyl red by TiO2: Comparison of the efficiency of immobilized nanoparticles versus conventional suspended catalyst. J. Hazard. Mater. 2007, 142, 130–137.

- Zheng, X.; Shen, Z.P.; Shi, L.; Cheng, R.; Yuan, D.H. Photocatalytic Membrane Reactors (PMRs) in Water Treatment: Configurations and Influencing Factors. Catalysts 2017, 7, 224.

- Riaz, S.; Park, S.-J. An overview of TiO2-based photocatalytic membrane reactors for water and wastewater treatments. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2020, 84, 23–41.

- Cheng, R.; Shen, L.J.; Wang, Q.; Xiang, S.Y.; Shi, L.; Zheng, X.; Lv, W.Z. Photocatalytic Membrane Reactor (PMR) for Virus Removal in Drinking Water: Effect of Humic Acid. Catalysts 2018, 8, 284.

- Jiang, L.; Zhang, X.; Choo, K.-H. Submerged microfiltration-catalysis hybrid reactor treatment: Photocatalytic inactivation of bacteria in secondary wastewater effluent. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2018, 198, 87–92.

- Amarjargal, A.; Tijing, L.D.; Ruelo, M.T.G.; Lee, D.H.; Kim, C.S. Facile synthesis and immobilization of Ag-TiO2 nanoparticles on electrospun PU nanofibers by polyol technique and simple immersion. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2012, 135, 277–281.

- Liu, L.; Liu, Z.Y.; Bai, H.W.; Sun, D.D. Concurrent filtration and solar photocatalytic disinfection/degradation using high-performance Ag/TiO2 nanofiber membrane. Water Res. 2012, 46, 1101–1112.

- Daels, N.; Radoicic, M.; Radetic, M.; De Clerck, K.; Van Hulle, S.W.H. Electrospun nanofibre membranes functionalised with TiO2 nanoparticles: Evaluation of humic acid and bacterial removal from polluted water. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2015, 149, 488–494.

- Zheng, X.; Shen, Z.-p.; Cheng, C.; Shi, L.; Cheng, R.; Yuan, D.-H. Photocatalytic disinfection performance in virus and virus/bacteria system by Cu-TiO2 nanofibers under visible light. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 237, 452–459.

- Nazerah, A.; Ismail, A.F.; Jaafar, J. Incorporation of bactericidal nanomaterials in development of antibacterial membrane for biofouling mitigation: A mini review. J. Teknol. 2016, 78, 53–61.

- Donlan, R.M. Biofilms: Microbial life on surfaces. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2002, 8, 881–890.

- Haghighat, N.; Vatanpour, V.; Sheydaei, M.; Nikjavan, Z. Preparation of a novel polyvinyl chloride (PVC) ultrafiltration membrane modified with Ag/TiO2 nanoparticle with enhanced hydrophilicity and antibacterial activities. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2020, 237, 116374.

- Sotto, A.; Boromand, A.; Zhang, R.X.; Luis, P.; Arsuaga, J.M.; Kim, J.; Van der Bruggen, B. Effect of nanoparticle aggregation at low concentrations of TiO2 on the hydrophilicity, morphology, and fouling resistance of PES-TiO2 membranes. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2011, 363, 540–550.

- Kim, S.H.; Kwak, S.Y.; Sohn, B.H.; Park, T.H. Design of TiO2 nanoparticle self-assembled aromatic polyamide thin-film-composite (TFC) membrane as an approach to solve biofouling problem. J. Membr. Sci. 2003, 211, 157–165.

- Becerra, J.; Zaderenko, A.P.; Gomez-Moron, M.A.; Ortiz, P. Nanoparticles Applied to Stone Buildings. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 2019, 1–16.

- Colmenares, J.C.; Kuna, E. Photoactive Hybrid Catalysts Based on Natural and Synthetic Polymers: A Comparative Overview. Molecules 2017, 22, 790.

- Chen, J.; Poon, C.S. Photocatalytic construction and building materials: From fundamentals to applications. Build. Environ. 2009, 44, 1899–1906.

- Dyshlyuk, L.; Babich, O.; Ivanova, S.; Vasilchenco, N.; Atuchin, V.; Korolkov, I.; Russakov, D.; Prosekov, A. Antimicrobial potential of ZnO, TiO2 and SiO2 nanoparticles in protecting building materials from biodegradation. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2020, 146, 8.

- Wu, Q.; Zhang, Z.H. The Fabrication of Magnetically Recyclable La-Doped TiO2/Calcium Ferrite/Diatomite Composite for Visible-Light-Driven Degradation of Antibiotic and Disinfection of Bacteria. Environ. Eng. Sci. 2020, 37, 109–119.

- Chen, L.; Pan, H.; Zhuang, C.F.; Peng, M.Y.; Zhang, L. Joint wound healing using polymeric dressing of chitosan/strontium-doped titanium dioxide with high antibacterial activity. Mater. Lett. 2020, 268, 3.

- Chan, B.P.; Leong, K.W. Scaffolding in tissue engineering: General approaches and tissue-specific considerations. Eur. Spine J. 2008, 17, S467–S479.

- Ahmed, A.; Niazi, M.B.K.; Jahan, Z.; Ahmad, T.; Hussain, A.; Pervaiz, E.; Janjua, H.A.; Hussain, Z. In-vitro and in-vivo study of superabsorbent PVA/Starch/g-C3N4/Ag@TiO2 NPs hydrogel membranes for wound dressing. Eur. Polym. J. 2020, 130, 109650.

- Malmir, S.; Karbalaei, A.; Pourmadadi, M.; Hamedi, J.; Yazdian, F.; Navaee, M. Antibacterial properties of a bacterial cellulose CQD-TiO2 nanocomposite. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 234, 10.

- Fan, X.L.; Chen, K.K.; He, X.C.; Li, N.; Huang, J.B.; Tang, K.Y.; Li, Y.J.; Wang, F. Nano-TiO2/collagen-chitosan porous scaffold for wound repairing. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 91, 15–22.

- Marulasiddeshwara, R.; Jyothi, M.S.; Soontarapa, K.; Keri, R.S.; Velmurugan, R. Nonwoven fabric supported, chitosan membrane anchored with curcumin/TiO2 complex: Scaffolds for MRSA infected wound skin reconstruction. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 144, 85–93.

- Ansarizadeh, M.; Haddadi, S.A.; Amini, M.; Hasany, M.; SaadatAbadi, A.R. Sustained release of CIP from TiO2-PVDF/starch nanocomposite mats with potential application in wound dressing. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2020, 137, 11.

- Ashraf, R.; Sofi, H.S.; Akram, T.; Rather, H.A.; Abdal-Hay, A.; Shabir, N.; Vasita, R.; Alrokayan, S.H.; Khan, H.A.; Sheikh, F.A. Fabrication of multifunctional cellulose/TiO2/Ag composite nanofibers scaffold with antibacterial and bioactivity properties for future tissue engineering applications. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2020, 108, 947–962.

- Jamróz, E.; Kulawik, P.; Kopel, P. The Effect of Nanofillers on the Functional Properties of Biopolymer-Based Films: A Review. Polymers 2019, 11, 675.

- Nazir, S.; Azad, Z.R.A.A. Food Nanotechnology: An Emerging Technology in Food Processing and Preservation. In Health and Safety Aspects of Food Processing Technologies; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 567–576.

- Bajpai, V.K.; Kamle, M.; Shukla, S.; Mahato, D.K.; Chandra, P.; Hwang, S.K.; Kumar, P.; Huh, Y.S.; Han, Y.-K. Prospects of using nanotechnology for food preservation, safety, and security. J. Food Drug Anal. 2018, 26, 1201–1214.

- Hoseinnejad, M.; Jafari, S.M.; Katouzian, I. Inorganic and metal nanoparticles and their antimicrobial activity in food packaging applications. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 44, 161–181.

- Sharma, R.; Jafari, S.M.; Sharma, S. Antimicrobial bio-nanocomposites and their potential applications in food packaging. Food Control 2020, 112, 11.

- Anaya-Esparza, L.M.; Ruvalcaba-Gomez, J.M.; Maytorena-Verdugo, C.I.; Gonzalez-Silva, N.; Romero-Toledo, R.; Aguilera-Aguirre, S.; Perez-Larios, A.; Montalvo-Gonzalez, E. Chitosan-TiO2: A Versatile Hybrid Composite. Materials 2020, 13, 811.

- Goudarzi, V.; Shahabi-Ghahfarrokhi, I.; Babaei-Ghazvini, A. Preparation of ecofriendly UV-protective food packaging material by starch/TiO2 bio-nanocomposite: Characterization. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 95, 306–313.

- Bohmer-Maas, B.W.; Fonseca, L.M.; Otero, D.M.; Zavareze, E.D.; Zambiazi, R.C. Photocatalytic zein-TiO2 nanofibers as ethylene absorbers for storage of cherry tomatoes. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2020, 24, 7.

- Youssef, A.M.; El-Sayed, S.M. Bionanocomposites materials for food packaging applications: Concepts and future outlook. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 193, 19–27.

- Zhang, X.D.; Xiao, G.; Wang, Y.Q.; Zhao, Y.; Su, H.J.; Tan, T.W. Preparation of chitosan-TiO2 composite film with efficient antimicrobial activities under visible light for food packaging applications. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 169, 101–107.

- Xie, J.; Hung, Y.C. UV-A activated TiO2 embedded biodegradable polymer film for antimicrobial food packaging application. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 96, 307–314.

- Hong, L.; Luo, S.H.; Yu, C.H.; Xie, Y.; Xia, M.Y.; Chen, G.Y.; Peng, Q. Functional Nanomaterials and Their Potential Applications in Antibacterial Therapy. Pharm. Nanotechnol. 2019, 7, 129–146.