Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gabriele Donati | -- | 2104 | 2022-11-10 12:37:43 | | | |

| 2 | Dean Liu | Meta information modification | 2104 | 2022-11-11 02:05:03 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Alfano, G.; Perrone, R.; Fontana, F.; Ligabue, G.; Giovanella, S.; Ferrari, A.; Gregorini, M.; Cappelli, G.; Magistroni, R.; Donati, G. Chronic Kidney Disease in the Aging Population. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/33949 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Alfano G, Perrone R, Fontana F, Ligabue G, Giovanella S, Ferrari A, et al. Chronic Kidney Disease in the Aging Population. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/33949. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Alfano, Gaetano, Rossella Perrone, Francesco Fontana, Giulia Ligabue, Silvia Giovanella, Annachiara Ferrari, Mariacristina Gregorini, Gianni Cappelli, Riccardo Magistroni, Gabriele Donati. "Chronic Kidney Disease in the Aging Population" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/33949 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Alfano, G., Perrone, R., Fontana, F., Ligabue, G., Giovanella, S., Ferrari, A., Gregorini, M., Cappelli, G., Magistroni, R., & Donati, G. (2022, November 10). Chronic Kidney Disease in the Aging Population. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/33949

Alfano, Gaetano, et al. "Chronic Kidney Disease in the Aging Population." Encyclopedia. Web. 10 November, 2022.

Copy Citation

The process of aging population will inevitably increase age-related comorbidities including chronic kidney disease (CKD). In light of this demographic transition, the lack of an age-adjusted CKD classification may enormously increase the number of new diagnoses of CKD in old subjects with an indolent decline in kidney function.

chronic kidney disease

aging

dialysis

palliative care

glomerular filtration rate

1. Introduction

Since 2013, the World Health Organization (WHO) has endorsed a project called “The Global Action Plan” aimed to promote health and psychophysical well-being of subjects worldwide. The goal of this program is to reduce mortality due to non-communicable diseases by 25% in 2025 through a wide action of prevention and control of risk factors [1].

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is recognized as a major public health problem affecting >10% of the global population. CKD is highly associated with morbidity and mortality and is linked to numerous negative effects that can potentially aggravate the outcome of the five most serious diseases (i.e., cardiovascular disease, diabetes, high blood pressure, HIV and malaria). Although CKD is not listed among the most clinically relevant chronic diseases, its management deserves careful consideration, because it has the potential to affect the prognosis of subjects and impact heavily on the resources of national healthcare systems [2].

CKD is a progressive chronic disease, leading to end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) in 1–2% of cases [3][4]. The Global Burden of Disease Study, an epidemiological study conducted in 195 countries, showed that kidney disease was responsible in 2015 for disability and reduced life expectancy by a cumulative 18 and 19 million years, respectively. The total number of reported death due to kidney disease accounted for 1.2 million yearly. This estimate was expected to rise to about 3–5 million/year people if mortality due to acute renal failure was included. However, the extent of the problem is likely underestimated, as access to laboratories for the screening of CKD is precluded in some geographical areas [5].

Kidney disease has the potential to involve all ages but is principally prevalent in older individuals. Aging is closely associated with kidney injury as advancing age is the major risk factor for kidney disease and age-related comorbidities. Aging is also implicated in the deleterious changes of kidney parenchyma secondary to cellular senescence as well as to cumulative effects of nephrotoxic agents prescribed during the patient’s life [6][7]. According to the latest projections, every country in the world is experiencing a rise in the number of older persons in their population. This subset of the population, at high risk of developing CKD, is projected to double in 2050 when one in six people in the world will be aged 65 years or over [8]. The current demographic transition will raise the prevalence of people with CKD. Consequently, the demand for care will pose a particular challenge to the concerning use of vast human and financial resources.

2. Definition and Staging of Chronic Kidney Disease in Adults

In 2002 the Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (KDOQI) guidelines defined the criteria for the diagnosis of CKD [9]. The further classifications substituted the previous definitions of nephropathy, relying on a series of poorly definable descriptive parameters and gave greater importance to the early stages of kidney disease in order to identify the disease preciously. According to the KDOQI guidelines and subsequent Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) modifications, CKD is characterized by a structural or functional dysfunction for ≥3 months. Glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and albuminuria are the two criteria utilized to classify CKD into “stages”. GFR divides kidney disease into five progressive stages while albuminuria identifies three additional categories for each level of kidney function. The combination of GFR (CKD stages, I–V) and albuminuria (A1–3) thresholds assumes also a prognostic significance, as classification in CKD staging predicts kidney survival [10]. However, three issues essentially limit the advantage of CKD classification in predicting the evolution of nephropathy and, above all, in planning an effective preventive strategy: assessment of albuminuria, methods for calculating GFR and the lack of a unanimously approved age-stratified CKD staging.

According to the 2009 KDIGO Controversies Conference report [11], albuminuria is a key criterion for the diagnosis of CKD. The magnitude of albuminuria may be easily misinterpreted because fluctuations are common in the real-word, and hypertension, cigarette smoking, inflammation and obesity may affect its excretion [12]. Furthermore, albuminuria may be overestimated in the elderly as reduced creatinine excretion secondary to the age-related decrease of muscle mass causes an increase in the urinary albumin/creatinine ratio. Lastly, to avoid overdiagnosis of CKD, the criterion of albuminuria should be met over at least 3 months of observation.

CKD prevalence estimations are influenced by population characteristics and different laboratory methods [13][14]. Ideally, to have an accurate estimate of GFR, it should be measured with nuclear medicine procedures, because formulae based on serum creatinine are characterized by several and well-known limitations [15]. Cystatin C provides an accurate alternative for measuring GFR. It is a reliable endogenous marker for the evaluation of kidney function compared to creatinine. Cystatin is not dependent on muscle conditions, therefore is more suitable in elderly patients with sarcopenia. Despite these advantages, its concentration is influenced by factors such as smoking, obesity, and inflammation [16][17]. The clearance of substances such as inulin, iohexol and iothalamate, allows a very precise measurement of renal function, excluding interfering variables such as age, body weight, muscle mass or inflammatory status from the calculation. Unfortunately, the availability of instrumentation in peripheral laboratory settings and lack of standardization potentially hamper comparisons across studies.

The Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation currently represents the most correct calculation method for estimating GFR in the general population. This equation overcomes the limit of the Cockcroft–Gault equation [18] (overestimation of GFR in obese people) [19] and MDRD (underestimation of GFR in people with normal or slightly reduced renal function [GFR between 60 to 100 mL/min]) [20].

The main limitation of the CKD-EPI equation is the tendency to overestimate GFR in the elderly. To overcome this discontinuity, which may have severe repercussions on renal function assessment and drug dose adaptation, a study conducted on white German participants aged >70 years with a mean measured GFR of 16–117 mL/min proposed the BIS-1 and BIS-2 GFR estimating equations [21]. These promising equations, albeit furnishing a precise and accurate tool to assess renal function in the elderly, still lack external validation studies against the KDIGO-recommended CKD-EPI equation. This latter also confirmed its superior performance when compared to the recent Lund–Malmö [22], FAS (Full Age Spectrum) [23] and CAPA (Caucasian and Asian Pediatric and Adult Subjects) [24] equations in the adult population.

In the absence of urinary alterations, the diagnosis of CKD is made by a GFR less than 60 mL/min. The use of a fixed threshold value across all age categories is undoubtedly a limiting element for the definition of CKD in the most extreme age groups of the population (i.e., young and elderly people). In these two groups, a similar value of GFR underlies a different prognostic value of kidney function, since projected life expectancies are poorly comparable. Based on these data, the classification of kideny function, embedded in a “rigid” staging system, may lead to inaccurate estimates of kidney outcomes. A classic example is the diagnosis of CKD in “healthy” old patients with a physiological decrease in kidney function.

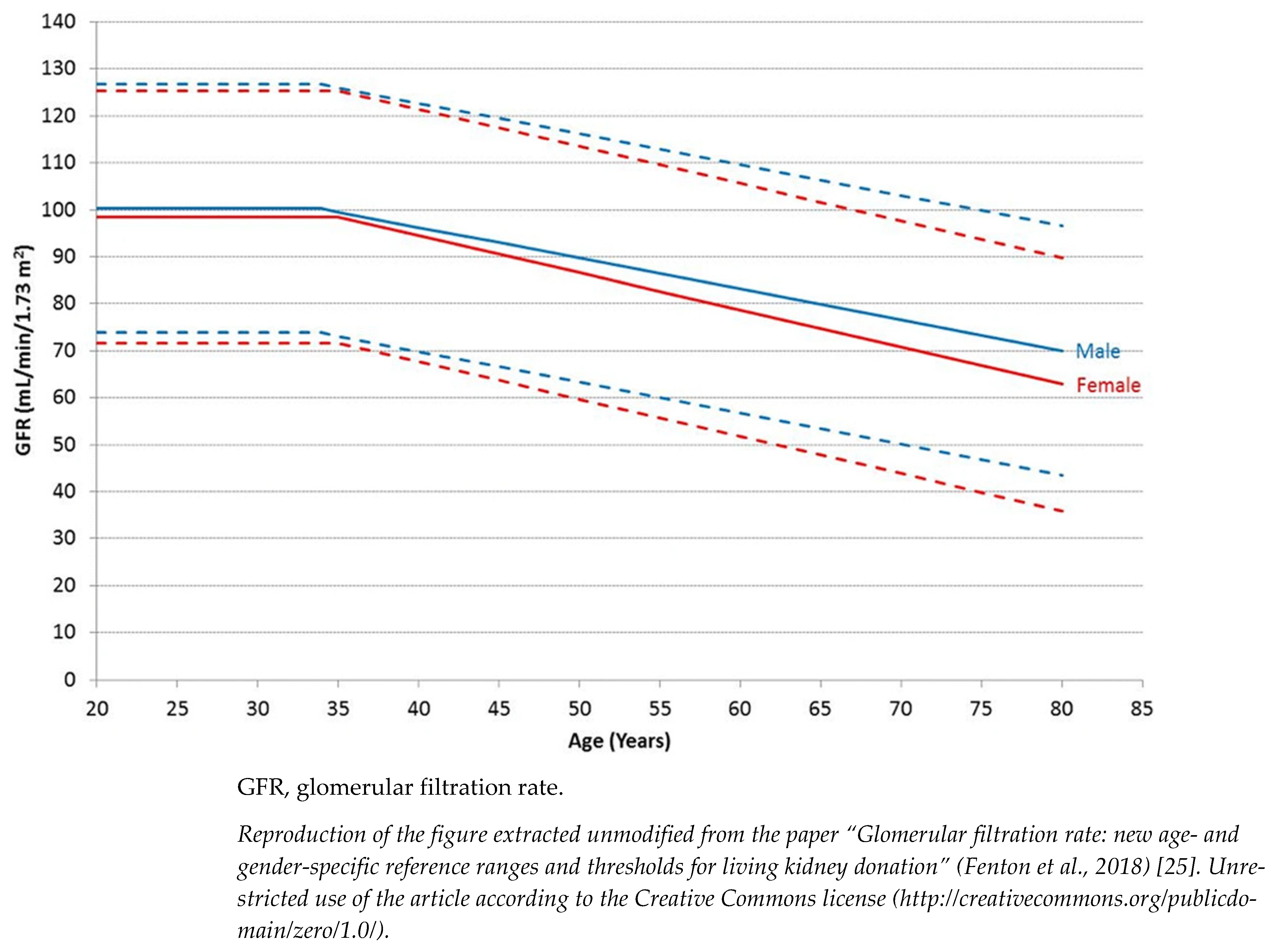

The current classification of CKD indeed does not separate kidney disease from kidney senescence, a physiological phenomenon occurring after 40 years of age (Figure 1) [25]. In support of this theory, histological evaluation of kidneys from elderly donors confirms a non-specific and generalized involution of the renal parenchyma. Evaluation of kidney biopsy revealed nephroangiosclerosis, global ischemia, tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis as well as a considerable reduction in the total number of nephrons in the absence of a real compensatory adaptation [26]. The decline of the filtrate usually becomes significant after 40 years of age regardless of the ethnicity of the population examined. Beyond this age, the decline in GFR is constant and could reach the lower normal limit of 45 mL/min in subjects aged more than 65 years.

Figure 1. Age- and gender-specific GFR reference ranges. Data include pre-donation mean GFR from 2974 prospective living kidney donors from 18 UK renal centers performed between 2003 and 2015. Solid lines represent mean GFR and interrupted lines are two standard deviations above and below the mean.

A meta-analysis conducted by the “CKD Prognosis Consortium” showed that the risk of ESKD and mortality is generally increased when GFR is substantially lower than 60 mL/min, but surprisingly, this threshold is lower in elderly patients [27]. Indeed, the elderly population with a GFR between 45 and 59 mL/min/1.73 m2, in the absence of urinary anomalies, tends rarely to progress towards ESKD (<1% at 5 years) [28].

Epidemiological studies have also reported that patients aged more than 65 years have a considerably higher risk of CKD progression only when the GFR is less than 45 mL/min. In support of the thesis, the “Renal Risk in Derby” study, conducted on 1741 people with a mean age of 72.9 ± 9 years and with an average GFR of 54 ± 12 mL/min/1.73 m2, confirmed that patients with stage IIIa of CKD have a mortality risk lower than CKD stage IIIb and IV and more importantly, these patients had a similar survival rate than the general population [29]. Based on these data, Delanaye et al. [30] proposed a CKD staging stratified according to three age categories: <40, 40–65 and >65 years. A GFR threshold of 75 mL/min should be considered “normal” for patients aged less than 40 years, 60 mL/min for individuals aged 40–65 years and 45 mL/min for the oldest (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Age-related threshold for diagnosis of CKD.

In other words, nephrological evaluation of the elderly patient with a reduction of GFR can no longer depend on a laboratory reporting system that defines GFR > 60 mL/min as normal. The use of a fixed threshold at 60 mL/min may induce misinterpretation of renal function. For instance, GFR slightly greater than 60 mL/min is a strong negative predictor of renal and patient survival in young patients. On the contrary, GFR slightly below 60 mL/min without urinary alterations in a patient aged >65 years represents a physiological condition not subject to further diagnostic investigations.

The evaluation of kidney function is also key in the setting of living kidney transplantation as post-donation GFR should remain within normal range without affecting the donor’s survival and the recipient should receive a healthy graft not affected by CKD. The correct interpretation of the donor’s kidney function is complex and must take into account the physiologic reduction of GFR with aging as well as potential comorbidities and lifetime risk of developing ESKD after donation [31]. In parallel to the age-adapted threshold for diagnosis of CKD in the general population, UK guidelines for kidney transplantation have released advisory threshold GFR levels for living kidney donation. As expected, the GFR threshold for performing a safe living kidney donation decreases with aging. In donors aged >30 years, it can range from 80 to 58 mL/min in males and from 80–49 mL/min in females [32].

3. Epidemiology of CKD

According to current estimates, about 700 million people are affected by CKD worldwide. The worldwide prevalence of CKD stage I–V is estimated between 3% and 18%, with a higher prevalence in women than males in patients older than 40 years [33]. Recent estimates (2015-2018) of CKD in the United States (US) showed that the overall prevalence of CKD, defined as eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 or urinary ACR ≥30 mg/g, in the adult US population is 14.4%. Most of the CKD population (93.7%) is affected by stages I and II, namely, early stages of kidney disease characterized by a mild decrease in their GFR (>60 mL/min). The distribution of patients based on KDIGO risk categories indicates that 1.3% of the CKD population is at high risk to progress toward kidney failure and receive RRT. As aforementioned, CKD is common in elderly patients [4]. About 40% of subjects living with GFR < 60 mL/min are aged 65 years old or older [4].

Demographic characteristics, quality of healthcare, socio-cultural level of the population and methods used for the evaluation of renal function are the main factors influencing the rate of CKD [34]. The differences in the rate of CKD increase especially between populations with different socio-cultural differences. Age-adjusted CKD prevalence ranges between 5.5% in people living in Spain and 13.7% in those living in Russia [14]. One glaring and surprising example is the considerable difference in the rate of CKD that has been found between counties with similar socio-economic and cultural profiles such as Norway (3.3%) and northeast Germany (17.1%) [35]. However, these results need to be interpreted with caution because different factors contribute to these epidemiological disparities. First, most studies are conducted in single regions or cities and, therefore, are poorly representative of the entire national territory. Second, modifiable factors such as genetic susceptibility [36][37][38] and environmental background (i.e., dietary pattern, infections, air pollution) [39][40][41][42] may drive many risk factors for the development of CKD.

References

- Mehta, R.L.; Cerdá, J.; Burdmann, E.A.; Tonelli, M.; García-García, G.; Jha, V.; Susantitaphong, P.; Rocco, M.; Vanholder, R.; Sever, M.S.; et al. International Society of Nephrology’s 0by25 Initiative for Acute Kidney Injury (Zero Preventable Deaths by 2025): A Human Rights Case for Nephrology. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2015, 385, 2616–2643.

- Cockwell, P.; Fisher, L.-A. The Global Burden of Chronic Kidney Disease. Lancet 2020, 395, 662–664.

- Boenink, R.; Astley, M.E.; Huijben, J.A.; Stel, V.S.; Kerschbaum, J.; Ots-Rosenberg, M.; Åsberg, A.A.; Lopot, F.; Golan, E.; Castro de la Nuez, P.; et al. The ERA Registry Annual Report 2019: Summary and Age Comparisons. Clin. Kidney J. 2022, 15, 452–472.

- United States Renal Data System. 2021 USRDS Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States; National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2021. Available online: https://adr.usrds.org/ (accessed on 14 October 2022).

- Bikbov, B.; Purcell, C.A.; Levey, A.S.; Smith, M.; Abdoli, A.; Abebe, M.; Adebayo, O.M.; Afarideh, M.; Agarwal, S.K.; Agudelo-Botero, M.; et al. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Chronic Kidney Disease, 1990–2017: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2020, 395, 709–733.

- Kaplan, C.; Pasternack, B.; Shah, H.; Gallo, G. Age-Related Incidence of Sclerotic Glomeruli in Human Kidneys. Am. J. Pathol. 1975, 80, 227.

- Perazella, M.A.; Rosner, M.H. Drug-Induced Acute Kidney Injury. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2022, 17, 1220–1233.

- United Nations. Ageing. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/global-issues/ageing (accessed on 16 September 2022).

- National Kidney Foundation K/DOQI Clinical Practice Guidelines for Chronic Kidney Disease: Evaluation, Classification, and Stratification. Am. J. Kidney Dis. Off. J. Natl. Kidney Found. 2002, 39, S1–S266.

- Levin, A.; Stevens, P.E.; Bilous, R.W.; Coresh, J.; Francisco, A.L.M.D.; Jong, P.E.D.; Griffith, K.E.; Hemmelgarn, B.R.; Iseki, K.; Lamb, E.J.; et al. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2012 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int. Suppl. 2013, 3, 1–150.

- Levey, A.S.; de Jong, P.E.; Coresh, J.; El Nahas, M.; Astor, B.C.; Matsushita, K.; Gansevoort, R.T.; Kasiske, B.L.; Eckardt, K.-U. The Definition, Classification, and Prognosis of Chronic Kidney Disease: A KDIGO Controversies Conference Report. Kidney Int. 2011, 80, 17–28.

- Winearls, C.G.; Glassock, R.J. Classification of Chronic Kidney Disease in the Elderly: Pitfalls and Errors. Nephron Clin. Pract. 2011, 119, c2–c4.

- Brück, K.; Jager, K.J.; Dounousi, E.; Kainz, A.; Nitsch, D.; Ärnlöv, J.; Rothenbacher, D.; Browne, G.; Capuano, V.; Ferraro, P.M.; et al. Methodology Used in Studies Reporting Chronic Kidney Disease Prevalence: A Systematic Literature Review. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2015, 30, iv6–iv16.

- van Rijn, M.H.C.; Alencar de Pinho, N.; Wetzels, J.F.; van den Brand, J.A.J.G.; Stengel, B. Worldwide Disparity in the Relation Between CKD Prevalence and Kidney Failure Risk. Kidney Int. Rep. 2020, 5, 2284–2291.

- Gaspari, F.; Perico, N.; Remuzzi, G. Measurement of Glomerular Filtration Rate. Kidney Int. Suppl. 1997, 63, S151–S154.

- Randers, E.; Erlandsen, E.J. Serum Cystatin C as an Endogenous Marker of the Renal Function—A Review. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 1999, 37, 389–395.

- Noronha, I.L.; Santa-Catharina, G.P.; Andrade, L.; Coelho, V.A.; Jacob-Filho, W.; Elias, R.M. Glomerular Filtration in the Aging Population. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 769329.

- Cockcroft, D.W.; Gault, M.H. Prediction of Creatinine Clearance from Serum Creatinine. Nephron 1976, 16, 31–41.

- Lemoine, S.; Guebre-Egziabher, F.; Sens, F.; Nguyen-Tu, M.-S.; Juillard, L.; Dubourg, L.; Hadj-Aissa, A. Accuracy of GFR Estimation in Obese Patients. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. CJASN 2014, 9, 720–727.

- Levey, A.S.; Coresh, J.; Greene, T.; Stevens, L.A.; Zhang, Y.L.; Hendriksen, S.; Kusek, J.W.; Van Lente, F. Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration Using Standardized Serum Creatinine Values in the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Equation for Estimating Glomerular Filtration Rate. Ann. Intern. Med. 2006, 145, 247–254.

- Schaeffner, E.S.; Ebert, N.; Delanaye, P.; Frei, U.; Gaedeke, J.; Jakob, O.; Kuhlmann, M.K.; Schuchardt, M.; Tölle, M.; Ziebig, R.; et al. Two Novel Equations to Estimate Kidney Function in Persons Aged 70 Years or Older. Ann. Intern. Med. 2012, 157, 471–481.

- Nyman, U.; Grubb, A.; Larsson, A.; Hansson, L.-O.; Flodin, M.; Nordin, G.; Lindström, V.; Björk, J. The Revised Lund-Malmö GFR Estimating Equation Outperforms MDRD and CKD-EPI across GFR, Age and BMI Intervals in a Large Swedish Population. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2014, 52, 815–824.

- Pottel, H.; Hoste, L.; Dubourg, L.; Ebert, N.; Schaeffner, E.; Eriksen, B.O.; Melsom, T.; Lamb, E.J.; Rule, A.D.; Turner, S.T.; et al. An Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate Equation for the Full Age Spectrum. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. Off. Publ. Eur. Dial. Transpl. Assoc.—Eur. Ren. Assoc. 2016, 31, 798–806.

- Grubb, A.; Horio, M.; Hansson, L.-O.; Björk, J.; Nyman, U.; Flodin, M.; Larsson, A.; Bökenkamp, A.; Yasuda, Y.; Blufpand, H.; et al. Generation of a New Cystatin C–Based Estimating Equation for Glomerular Filtration Rate by Use of 7 Assays Standardized to the International Calibrator. Clin. Chem. 2014, 60, 974–986.

- Fenton, A.; Montgomery, E.; Nightingale, P.; Peters, A.M.; Sheerin, N.; Wroe, A.C.; Lipkin, G.W. Glomerular Filtration Rate: New Age- and Gender- Specific Reference Ranges and Thresholds for Living Kidney Donation. BMC Nephrol. 2018, 19, 336.

- Denic, A.; Glassock, R.J.; Rule, A.D. Structural and Functional Changes with the Aging Kidney. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 2016, 23, 19–28.

- Hallan, S.I.; Matsushita, K.; Sang, Y.; Mahmoodi, B.K.; Black, C.; Ishani, A.; Kleefstra, N.; Naimark, D.; Roderick, P.; Tonelli, M.; et al. Age and Association of Kidney Measures with Mortality and End-Stage Renal Disease. JAMA 2012, 308, 2349–2360.

- Tangri, N.; Stevens, L.A.; Griffith, J.; Tighiouart, H.; Djurdjev, O.; Naimark, D.; Levin, A.; Levey, A.S. A Predictive Model for Progression of Chronic Kidney Disease to Kidney Failure. JAMA 2011, 305, 1553–1559.

- Shardlow, A.; McIntyre, N.J.; Fluck, R.J.; McIntyre, C.W.; Taal, M.W. Chronic Kidney Disease in Primary Care: Outcomes after Five Years in a Prospective Cohort Study. PLoS Med. 2016, 13, e1002128.

- Delanaye, P.; Jager, K.J.; Bökenkamp, A.; Christensson, A.; Dubourg, L.; Eriksen, B.O.; Gaillard, F.; Gambaro, G.; van der Giet, M.; Glassock, R.J.; et al. CKD: A Call for an Age-Adapted Definition. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. JASN 2019, 30, 1785–1805.

- Garg, N.; Poggio, E.D.; Mandelbrot, D. The Evaluation of Kidney Function in Living Kidney Donor Candidates. Kidney360 2021, 2, 1523–1530.

- Guidelines for Living Donor Kidney Transplantation. British Transplantation Society. Www.Bts.Org.Uk. March 2018 Fourth Edition. Available online: https://Bts.Org.Uk/Wp-Content/Uploads/2018/07/FINAL_LDKT-Guidelines_June-2018.Pdf (accessed on 18 September 2022).

- Glassock, R.J.; Warnock, D.G.; Delanaye, P. The Global Burden of Chronic Kidney Disease: Estimates, Variability and Pitfalls. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2017, 13, 104–114.

- Mills, K.T.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Bundy, J.D.; Chen, C.-S.; Kelly, T.N.; Chen, J.; He, J. A Systematic Analysis of Worldwide Population-Based Data on the Global Burden of Chronic Kidney Disease in 2010. Kidney Int. 2015, 88, 950–957.

- Brück, K.; Stel, V.S.; Gambaro, G.; Hallan, S.; Völzke, H.; Ärnlöv, J.; Kastarinen, M.; Guessous, I.; Vinhas, J.; Stengel, B.; et al. CKD Prevalence Varies across the European General Population. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. JASN 2016, 27, 2135–2147.

- Lei, H.H.; Perneger, T.V.; Klag, M.J.; Whelton, P.K.; Coresh, J. Familial Aggregation of Renal Disease in a Population-Based Case-Control Study. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 1998, 9, 1270–1276.

- Gumprecht, J.; Zychma, M.J.; Moczulski, D.K.; Gosek, K.; Grzeszczak, W. Family History of End-Stage Renal Disease among Hemodialyzed Patients in Poland. J. Nephrol. 2003, 16, 511–515.

- Satko, S.G.; Freedman, B.I.; Moossavi, S. Genetic Factors in End-Stage Renal Disease. Kidney Int. 2005, 67, S46–S49.

- Prasad, N.; Patel, M.R. Infection-Induced Kidney Diseases. Front. Med. 2018, 5, 327.

- Kuźma, Ł.; Małyszko, J.; Bachórzewska-Gajewska, H.; Kralisz, P.; Dobrzycki, S. Exposure to Air Pollution and Renal Function. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 11419.

- Asghari, G.; Farhadnejad, H.; Mirmiran, P.; Dizavi, A.; Yuzbashian, E.; Azizi, F. Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet Is Associated with Reduced Risk of Incident Chronic Kidney Diseases among Tehranian Adults. Hypertens. Res. 2017, 40, 96–102.

- Nettleton, J.A.; Steffen, L.M.; Palmas, W.; Burke, G.L.; Jacobs, D.R. Associations between Microalbuminuria and Animal Foods, Plant Foods, and Dietary Patterns in the Multiethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 87, 1825–1836.

More

Information

Subjects:

Urology & Nephrology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.5K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

11 Nov 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No