| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Beatrix Zheng | -- | 1742 | 2022-11-10 01:35:53 | | | |

| 2 | Beatrix Zheng | Meta information modification | 1742 | 2022-11-10 04:22:28 | | |

Video Upload Options

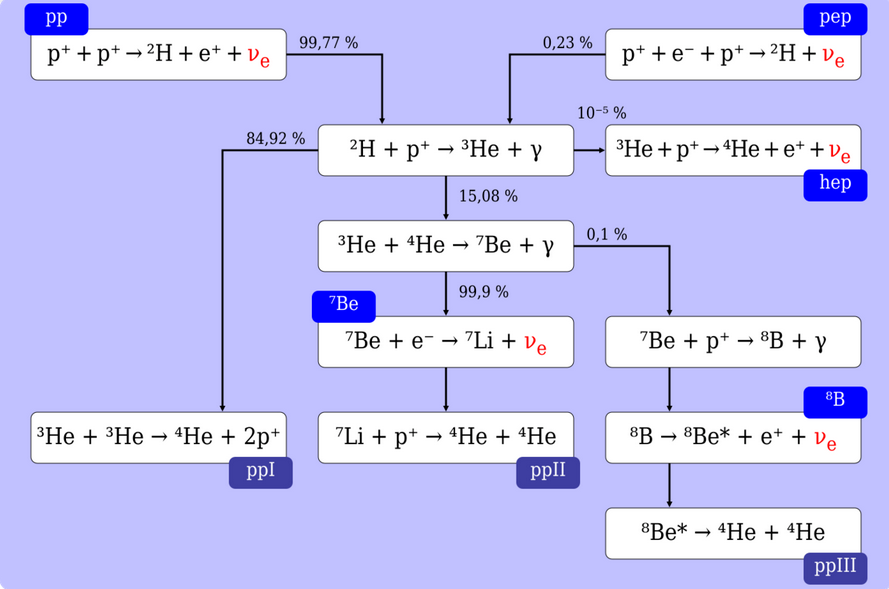

The proton–proton chain, also commonly referred to as the p-p chain, is one of two known sets of nuclear fusion reactions by which stars convert hydrogen to helium. It dominates in stars with masses less than or equal to that of the Sun, whereas the CNO cycle, the other known reaction, is suggested by theoretical models to dominate in stars with masses greater than about 1.3 times that of the Sun. In general, proton–proton fusion can occur only if the kinetic energy (i.e. temperature) of the protons is high enough to overcome their mutual electrostatic repulsion. In the Sun, deuterium-producing events are rare. Diprotons are the much more common result of proton–proton reactions within the star, and diprotons almost immediately decay back into two protons. Since the conversion of hydrogen to helium is slow, the complete conversion of the hydrogen initially in the core of the Sun is calculated to take more than ten billion years. Although sometimes called the "proton–proton chain reaction", it is not a chain reaction in the normal sense. In most nuclear reactions, a chain reaction designates a reaction that produces a product, such as neutrons given off during fission, that quickly induces another such reaction. The proton-proton chain is, like a decay chain, a series of reactions. The product of one reaction is the starting material of the next reaction. There are two main chains leading from Hydrogen to Helium in the Sun. One chain has five reactions, the other chain has six.

1. History of the Theory

The theory that proton–proton reactions are the basic principle by which the Sun and other stars burn was advocated by Arthur Eddington in the 1920s. At the time, the temperature of the Sun was considered to be too low to overcome the Coulomb barrier. After the development of quantum mechanics, it was discovered that tunneling of the wavefunctions of the protons through the repulsive barrier allows for fusion at a lower temperature than the classical prediction.

In 1939, Hans Bethe attempted to calculate the rates of various reactions in stars. Starting with two protons combining to give deuterium and a positron he found what we now call Branch II of the proton-proton chain. But he did not consider the reaction of two 3He nuclei (Branch I) which we now know to be important.[1] This was part of the body of work in stellar nucleosynthesis for which Bethe won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1967.

2. The Proton–Proton Chain

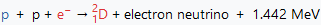

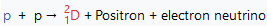

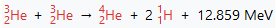

The first step in all the branches is the fusion of two protons into deuterium. As the protons fuse, one of them undergoes beta plus decay, converting into a neutron by emitting a positron and an electron neutrino[2] (though a small amount of deuterium is produced by the "pep" reaction, see below):

The positron will annihilate with an electron from the environment into two gamma rays. Including this annihilation and the energy of the neutrino, the net reaction

(which is the same as the PEP reaction, see below) has a Q value (released energy) of 1.442 MeV:[2] The relative amounts of energy going to the neutrino and to the other products is variable.

This is the rate-limiting reaction and is extremely slow due to it being initiated by the weak nuclear force. The average proton in the core of the Sun waits 9,000 million years before it successfully fuses with another proton. It has not been possible to measure the cross-section of this reaction experimentally because it is so low[3] but it can be calculated from theory.[4]

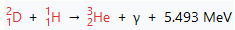

After it is formed, the deuterium produced in the first stage can fuse with another proton to produce the light isotope of helium, 3He:

This process, mediated by the strong nuclear force rather than the weak force, is extremely fast by comparison to the first step. It is estimated that, under the conditions in the Sun's core, each newly created deuterium nucleus exists for only about one second before it is converted into helium-3.[4]

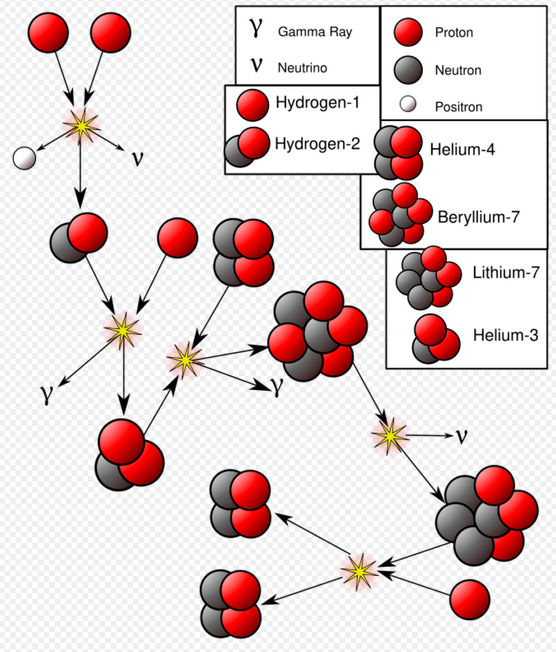

In the Sun, each helium-3 nucleus produced in these reactions exists for only about 400 years before it is converted into helium-4.[5] Once the helium-3 has been produced, there are four possible paths to generate 4He. In p–p I, helium-4 is produced by fusing two helium-3 nuclei; the p–p II and p–p III branches fuse 3He with pre-existing 4He to form beryllium-7, which undergoes further reactions to produce two helium-4 nuclei.

About 99% of the energy output of the sun comes from the various p-p chains, with the other 1% coming from the CNO cycle. According to one model of the sun, 83.3 percent of the 4He produced by the various p-p branches is produced via branch I while p–p II produces 16.68 percent and p–p III 0.02 percent.[4] Since half the neutrinos produced in branches II and III are produced in the first step (synthesis of deuterium), only about 8.35 percent of neutrinos come from the later steps (see below), and about 91.65 percent are from deuterium synthesis. However, another solar model from around the same time gives only 7.14 percent of neutrinos from the later steps and 92.86 percent from the synthesis of deuterium.[6] The difference is apparently due to slightly different assumptions about the composition and metallicity of the sun.

There is also the extremely rare p–p IV branch. Other even rarer reactions may occur. The rate of these reactions is very low due to very small cross-sections, or because the number of reacting particles is so low that any reactions that might happen are statistically insignificant.

The overall reaction is:

- 4 1H+ + 2e- → 4He2+ + 2νe

releasing 26.73 MeV of energy, some of which is lost to the neutrinos.

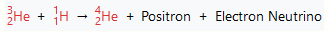

2.1. The P–P I Branch

The complete chain releases a net energy of 26.732 MeV[7] but 2.2 percent of this energy (0.59 MeV) is lost to the neutrinos that are produced.[8] The p–p I branch is dominant at temperatures of 10 to 14 MK.

2.2. The P–P II Branch

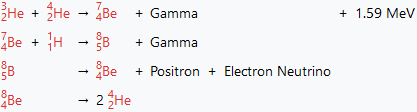

-

32He + 42He → 74Be + γ + 1.59 MeV 74Be + e− → 73Li− + νe + 0.861 MeV / 0.383 MeV 73Li + 11H → 242He + 17.35 MeV

The p–p II branch is dominant at temperatures of 14 to 23 MK.

Note that the energies in the second reaction above are the energies of the neutrinos that are produced by the reaction. 90 percent of the neutrinos produced in the reaction of 7Be to 7Li carry an energy of 0.861 MeV, while the remaining 10 percent carry 0.383 MeV. The difference is whether the lithium-7 produced is in the ground state or an excited (metastable) state, respectively. The total energy released going from 7Be to stable 7Li is about 0.862 MeV, almost all of which is lost to the neutrino if the decay goes directly to the stable lithium.

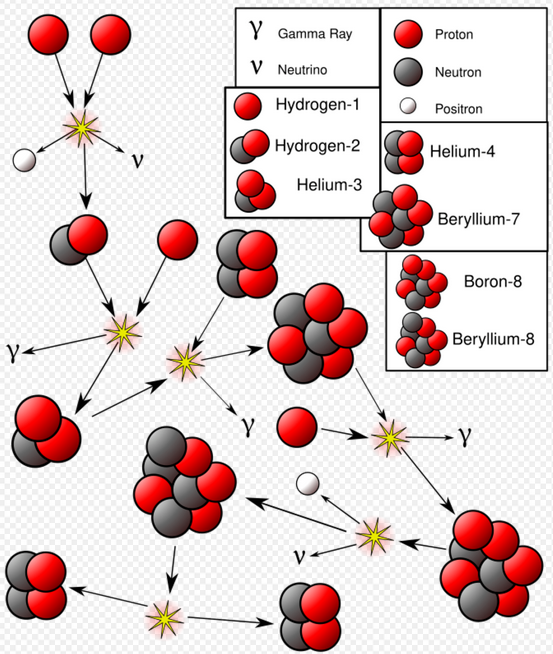

2.3. The P–P III branch

The last three stages of this chain, plus the positron annihilation, contribute a total of 18.209 MeV, though much of this is lost to the neutrino.

The p–p III chain is dominant if the temperature exceeds 23 MK.

The p–p III chain is not a major source of energy in the Sun, but it was very important in the solar neutrino problem because it generates very high energy neutrinos (up to 14.06 MeV).

2.4. The P–P IV (Hep) Branch

This reaction is predicted theoretically, but it has never been observed due to its rarity (about 0.3 ppm in the Sun). In this reaction, helium-3 captures a proton directly to give helium-4, with an even higher possible neutrino energy (up to 18.8 MeV).

The mass-energy relationship gives 19.795 MeV for the energy released by this reaction plus the ensuing annihilation, some of which is lost to the neutrino.

2.5. Energy Release

Comparing the mass of the final helium-4 atom with the masses of the four protons reveals that 0.7 percent of the mass of the original protons has been lost. This mass has been converted into energy, in the form of kinetic energy of produced particles, gamma rays, and neutrinos released during each of the individual reactions. The total energy yield of one whole chain is 26.73 MeV.

Energy released as gamma rays will interact with electrons and protons and heat the interior of the Sun. Also kinetic energy of fusion products (e.g. of the two protons and the 42He from the p–p I reaction) adds energy to the plasma in the Sun. This heating keeps the core of the Sun hot and prevents it from collapsing under its own weight as it would if the sun were to cool down.

Neutrinos do not interact significantly with matter and therefore do not heat the interior and thereby help support the Sun against gravitational collapse. Their energy is lost: the neutrinos in the p–p I, p–p II, and p–p III chains carry away 2.0%, 4.0%, and 28.3% of the energy in those reactions, respectively.[9]

The following table calculates the amount of energy lost to neutrinos and the amount of "solar luminosity" coming from the three branches. "Luminosity" here means the amount of energy given off by the Sun as electromagnetic radiation rather than as neutrinos. The starting figures used are the ones mentioned higher in this article. The table concerns only the 99% of the power and neutrinos that come from the p-p reactions, not the 1% coming from the CNO cycle.

| Branch | Percent of helium-4 produced | Percent loss due to neutrino production | Relative amount of energy lost | Relative amount of luminosity produced | Percentage of total luminosity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Branch I | 83.3 | 2 | 1.67 | 81.6 | 83.6 |

| Branch II | 16.68 | 4 | 0.67 | 16.0 | 16.4 |

| Branch III | 0.02 | 28.3 | 0.0057 | 0.014 | 0.015 |

| Total | 100 | 2.34 | 97.7 | 100 |

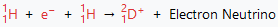

3. The PEP Reaction

Deuterium can also be produced by the rare pep (proton–electron–proton) reaction (electron capture):

In the Sun, the frequency ratio of the pep reaction versus the p–p reaction is 1:400. However, the neutrinos released by the pep reaction are far more energetic: while neutrinos produced in the first step of the p–p reaction range in energy up to 0.42 MeV, the pep reaction produces sharp-energy-line neutrinos of 1.44 MeV. Detection of solar neutrinos from this reaction were reported by the Borexino collaboration in 2012.[10]

Both the pep and p–p reactions can be seen as two different Feynman representations of the same basic interaction, where the electron passes to the right side of the reaction as a positron. This is represented in the figure of proton–proton and electron-capture reactions in a star, available at the NDM'06 web site.[11]

References

- Hans Bethe (Mar 1, 1939). "Energy Production in Stars". Physical Review 55 (5): 434–456. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.55.434. Bibcode: 1939PhRv...55..434B. https://dx.doi.org/10.1103%2FPhysRev.55.434

- Iliadis, Christian (2007). Nuclear Physics of Stars. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. ISBN 9783527406029. OCLC 85897502. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/85897502

- Phillips, Anthony C. (1999). The Physics of Stars (2nd ed.). Chichester: John Wiley. ISBN 0471987972. OCLC 40948449. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/40948449

- Adelberger, Eric G. (12 April 2011). "Solar fusion cross sections. II. The pp chain and CNO cycles". Reviews of Modern Physics 83 (1): 201. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.83.195. Bibcode: 2011RvMP...83..195A. See Figure 2. The caption is not very clear but it has been confirmed that the percentages refer to how much of each reaction takes place, or equivalently how much helium-4 is produced by each branch. https://dx.doi.org/10.1103%2FRevModPhys.83.195

- This time and the two other times above come from: Byrne, J. Neutrons, Nuclei, and Matter, Dover Publications, Mineola, NY, 2011, ISBN:0486482383, p 8.

- Aldo Serenelli (Nov 2009). "New Solar Composition: The Problem With Solar Models Revisited". The Astrophysical Journal Letters 705 (2): L123–L127. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/705/2/L123. Bibcode: 2009ApJ...705L.123S. Calculated from model AGSS09 in Table 3. https://dx.doi.org/10.1088%2F0004-637X%2F705%2F2%2FL123

- LeBlanc, Francis. An Introduction to Stellar Astrophysics.

- Burbidge, E.; Burbidge, G.; Fowler, William; Hoyle, F. (1 October 1957). "Synthesis of the Elements in Stars". Reviews of Modern Physics 29 (4): 547–650. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.29.547. Bibcode: 1957RvMP...29..547B. https://dx.doi.org/10.1103%2FRevModPhys.29.547

- Claus E. Rolfs and William S. Rodney, Cauldrons in the Cosmos, The University of Chicago Press, 1988, p. 354.

- Bellini, G. (2 February 2012). "First Evidence of pep Solar Neutrinos by Direct Detection in Borexino". Physical Review Letters 108 (5): 051302. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.051302. PMID 22400925. Bibcode: 2012PhRvL.108e1302B. https://dx.doi.org/10.1103%2FPhysRevLett.108.051302

- Int'l Conference on Neutrino and Dark Matter, Thursday 07 Sept 2006, https://indico.lal.in2p3.fr/getFile.py/access?contribId=s16t1&sessionId=s16&resId=1&materialId=0&confId=a05162 Session 14.