The COVID-19 crisis and the war between Russia and Ukraine affects the world economy badly. The western countries’ economic sanctions on Russia and the Russian government’s reverse sanctions on western countries create pressure on the world economy. Countries over the world registered less economic growth, high inflation rate, and high government debt in 2022 compared to the fiscal period of 2019–2021. The emerging economies and developing countries of Europe were badly affected by the crisis as the level of inflation rate hit 27 percent and the economic growth of the region registered a negative 2.9 percent. It also found rising interest rates, exchange rate volatility, risk of stagflation, and rising energy prices are the short-term risks to economies. The issue of sustainable development goals and green aspects, risk of hyperinflation, and risk of economic recession are the long-term strategic challenges or risks to economies. Bailout and debt relief were found to be necessary for those countries badly affected by the crisis. Policymakers should facilitate financial policies and should switch from general assistance to targeted support of viable enterprises.

1. Introduction

It would be a great question to investigate “Does COVID-19 and the geopolitical crisis of the era suggest that peoplee need a new way of thinking about economics and the economy”? The question would certainly take to Keynes’ theory of 1936 from The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money. This theory developed and changed the way people thought about economics

[1].

The same is true today, not just in response to the COVID-19 crisis but to the era of seemingly multiple crises

[2]. As evidence, the Southeast Asian economic crisis in 1997 collapsed currency values, stock markets, and other asset values in many Southeast Asian countries

[3]. The 2007–2008 global financial crisis created the first global recession. The subprime mortgage crisis that resulted from 2007 to 2008 created a financial crisis that affected the United States and other countries in the world. At the same time, the pandemics such as smallpox, SARS, and currently COVID-19, and the rising concern about carbon emissions are those factors among others affecting the economy badly.

As a result of the COVID-19 outbreak, there have been numerous negative effects on human life all over the world

[4]. The ruthlessness of the pandemic is changing the focus of academics’ attention away from economic activity and onto human life

[5] (p. 19). People’s health is actually of utmost importance and saving lives must come first. However, economic forces continue to be important. Even knowing how much to invest for protection must depend in part on economic considerations

[6]. If more consideration was given to economic activities in a bid to fight the pandemic and other crises, fewer lives would have been lost. Furthermore, an uneconomical way of fighting the pandemic and other crises will create many short-term risks and long-term strategic challenges and will lead to an economic recession that will typically result in greater death rates (through a deterioration in physical and mental health, a rise in suicides, and so forth). The pandemic creates many economic challenges for both developed and developing countries

[7], as a result, many countries are facing structural breakdowns in macro-economic variables

[8]. The level of government debt stayed high and increased

[9], unemployment hit a peak

[10], economic growth declined, volatility in exchange rates were observed, and the level of trade, tourism, hospitality, manufacturing, transport, and so on decreased for all countries. Therefore, the economy, economics, and economic policy remain important to prepare the rest of world on the way forward

[11].

Apart from the COVID-19 pandemic, the war between Russia and Ukraine takes the level of crisis even further. The study conducted by

[12] shows that the Russia–Ukraine war hit Germany’s economy and the European Economic Area as a second major shock following the coronavirus pandemic. More specifically, the study highlights the risk of geopolitical disruptions and how they are forcing the German economy’s business models to adjust. The crisis added another challenge to global economies by harming growth and putting upward pressure on inflation when inflation was already at high levels in different countries

[13]. It also brings significant escalation in energy prices due to Russia being one of the world’s largest oil producers and energy exporters.

The political risk and uncertainty drive up savings ratios and makes firms more reluctant to invest, this could also slow inward foreign direct investment. Restrictions on exports would increase the reliance on money printing to finance the war, which leads to increasing upside inflation risks. New lenders will be wary and those anticipating loan payments will be anxious, share prices have decreased as risk premia on some European banks have increased

[14]. The collective impact of the crisis creates high pressure on different countries’ economies and politics. Particularly, the war caused Russia’s GDP to decline by 1.5% in 2022 and 2.6% in 2023 (compared to base) as forecasted by the IMF

[15]. The country’s currency (RUB) was devaluated dramatically at the beginning of the war. However, changing currency payments from USD to RUB for major Russian exports helps the currency of the country to recover

[15]. This is mainly related to the increase in Russian energy exports. On the other hand, the economic condition of emerging and developing Europe was affected badly as a result of the conflict

[15]. The 2022 GDP registers a negative 2.9 percent compared to the base year. Inflation hit 27 percent and energy price increased dramatically

[15]. The war has different implications across the regions. Those countries highly dependent on Russian energy (the Czech Republic, Germany, Hungary, Italy, and the Slovak Republic) are affected badly. As a result, it is shown the effect of increasing energy and food prices.

2. Consequences of Geopolitics and COVID-19 on Economic Performance

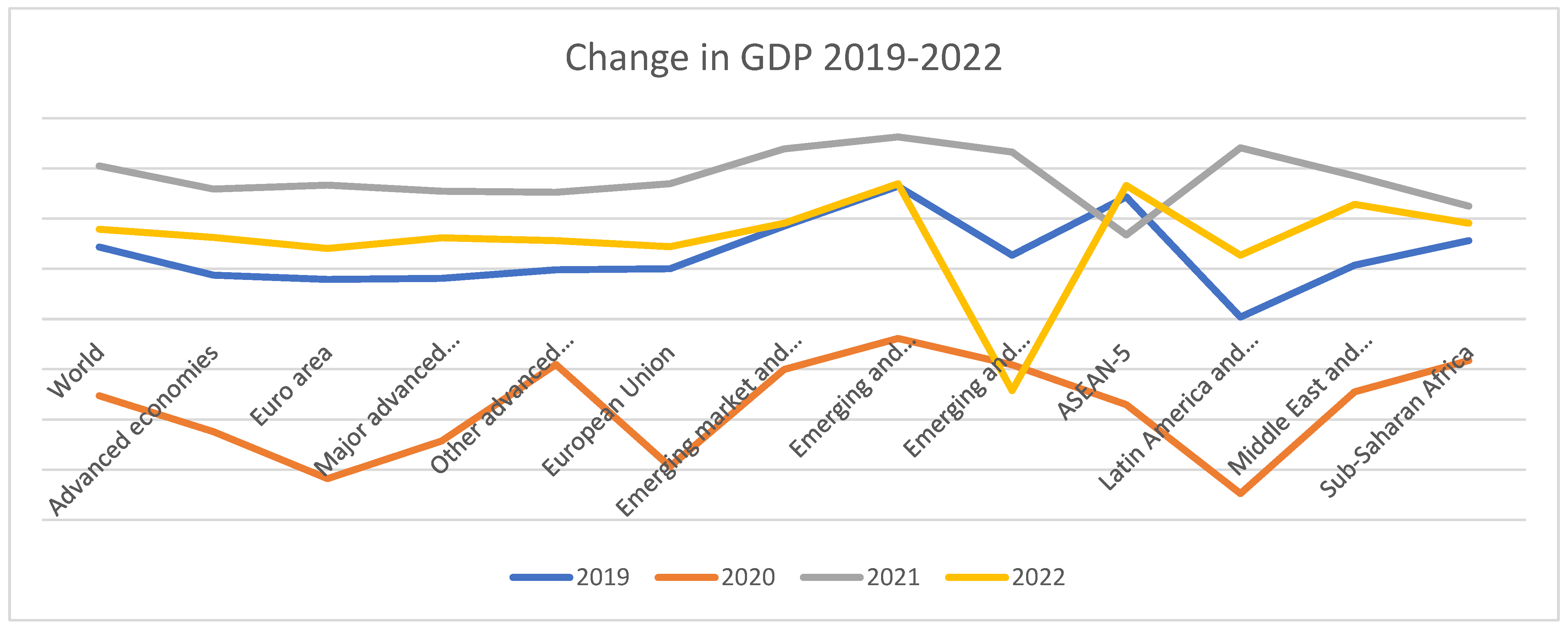

According to data extracted from the IMF database and presented in

Figure 1, 2020 was the worst for economic performance for all countries across the world; world economic growth was estimated as a negative 3 percent change, which is much less than 2019. Countries such as the major advanced economies (G7), the European Union, Latin America, and Caribbean countries registered the worst economic records of the era. This could be due to the spread of COVID-19 and the correction measurements taken to protect people through lockdowns. Besides, 2021 was the greatest year of economic recovery during the COVID-19 era. The world economy registered a growth of 6.1 percent in 2021

[15]. The majority of developed and developing countries recovered during this year. However, the recent IMF forecast of regional outlooks implies that the growth level registered in 2021 will be not repeated in 2022, as far as the forecasted result shows there will be 3.6 percent growth in the year 2022. The war between Russia and Ukraine plays a significant role in the downward registration of economic performance in 2022. More specifically, emerging and developing European countries are expected to register the worst economic record after 2020 as far IMF predicted a negative 2.9 percent economic decline. Despite the COVID-19 crisis and the Russia–Ukraine war, the IMF forecasts positive economic growth for the majority of countries across the world except for the emerging and developing countries of Europe.

Figure 1. Economic performance during the COVID-19 era for all continents. Source: IMF 2022.

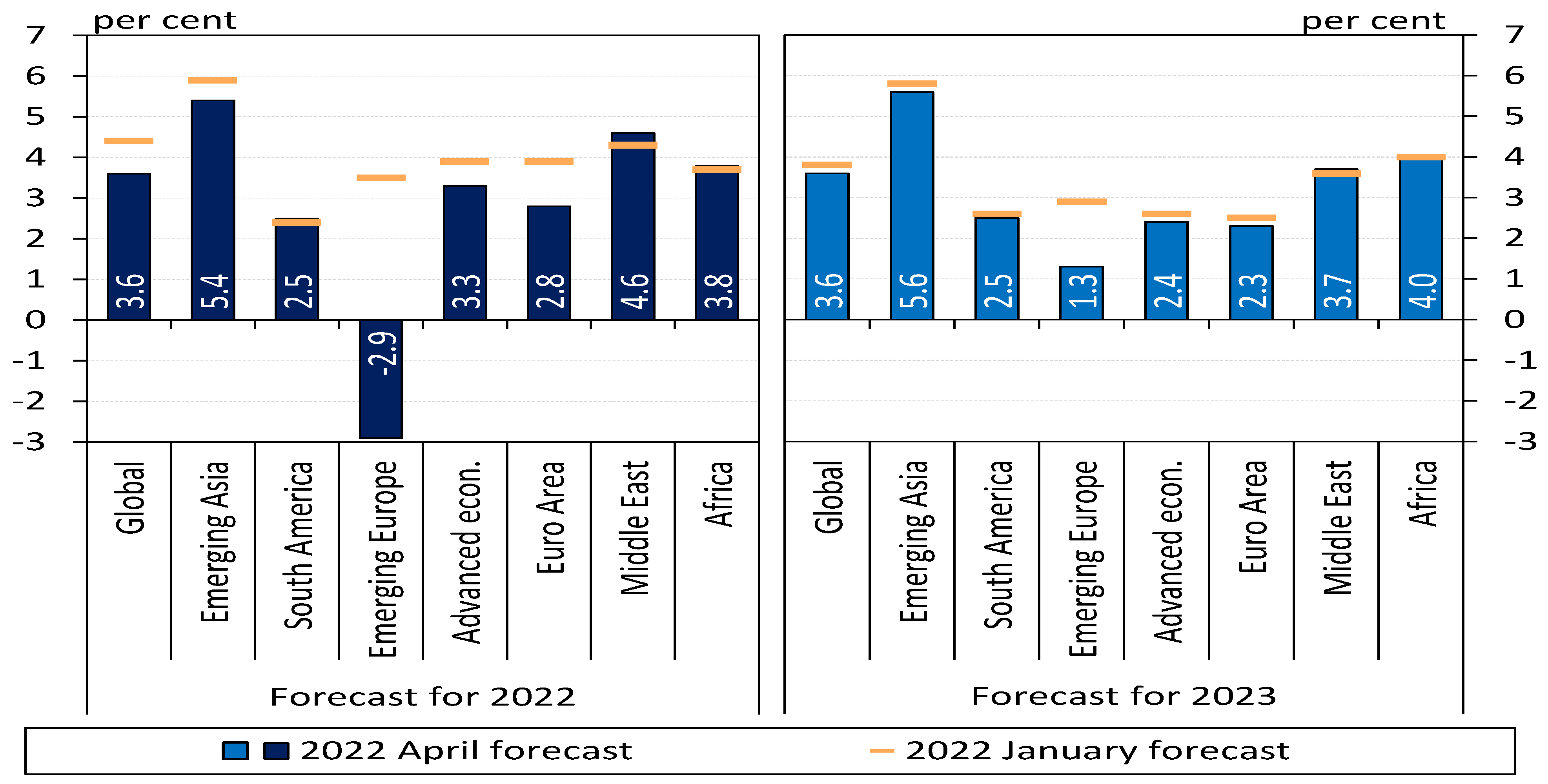

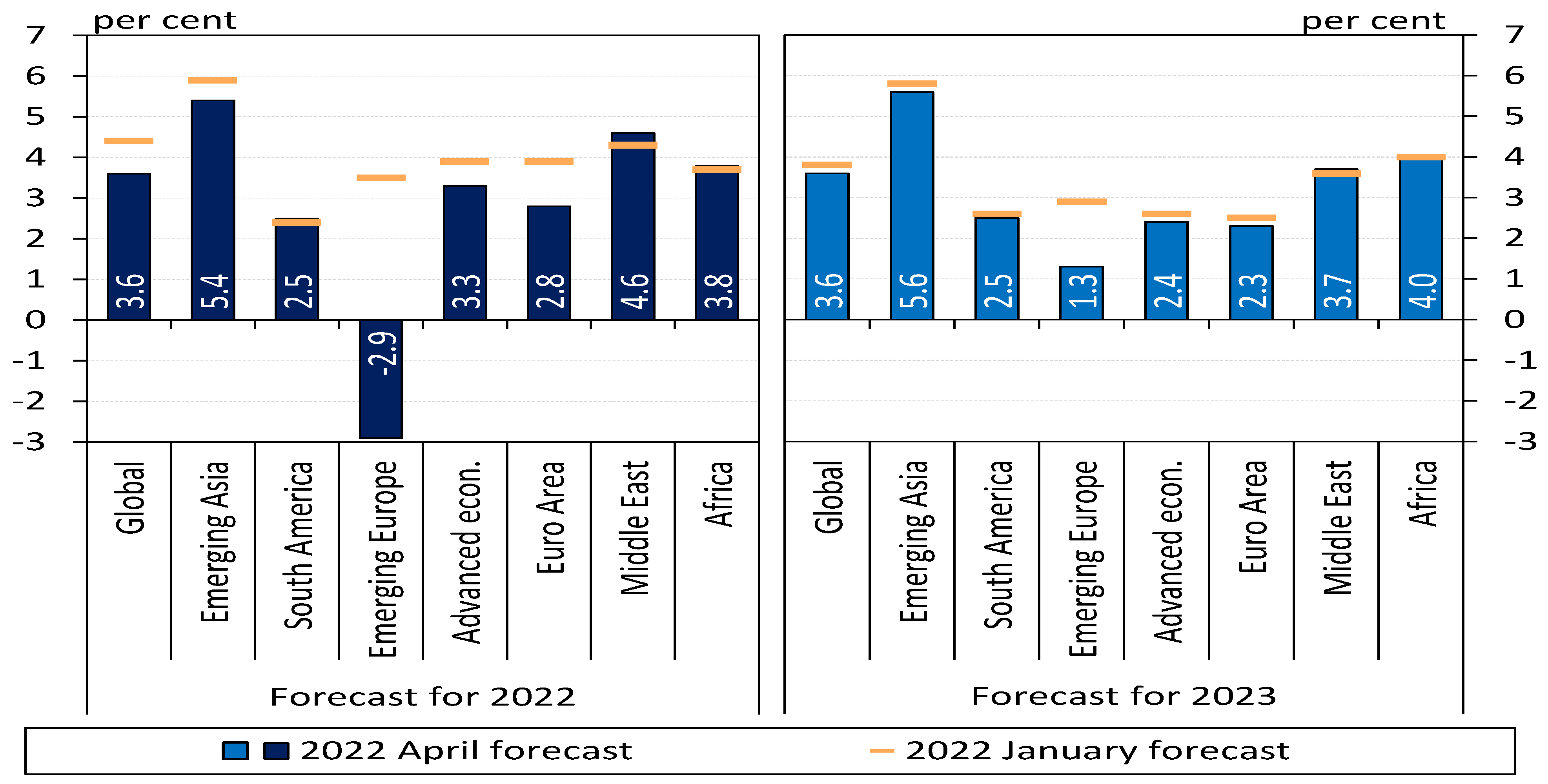

As seen in

Figure 2, even countries in Latin America, the Caribbean, Africa, and the Middle East are projected to register positive economic growth. The Latin American and Caribbean continent, which suffered the highest economic decline in 2020, is expected to register a growth of 2.5 percent. Hence, this could raise the question of why only the emerging and developing European countries are expected to register negative economic growth. This result is highly an indication of how the European continent (especially the emerging economies) was affected by the war between Russia and Ukraine. According to an IMF report of 2020, in the periods of two months since the outbreak of the war, about 5 million people, mostly women and children, have fled Ukraine and a further 7 million are estimated to be displaced internally. The refugee inflow into Europe has already exceeded that from Syria in 2015–2016

[16]. Countries that share borders with Ukraine, especially Poland but also Hungary, Moldova, Romania, and the Slovak Republic, are hosting most of these refugees and this could also be an additional factor that distorts the economic performance of the countries

[13].

Figure 2. Economic performance of 2022 for all continents. Source: IMF, 2022.

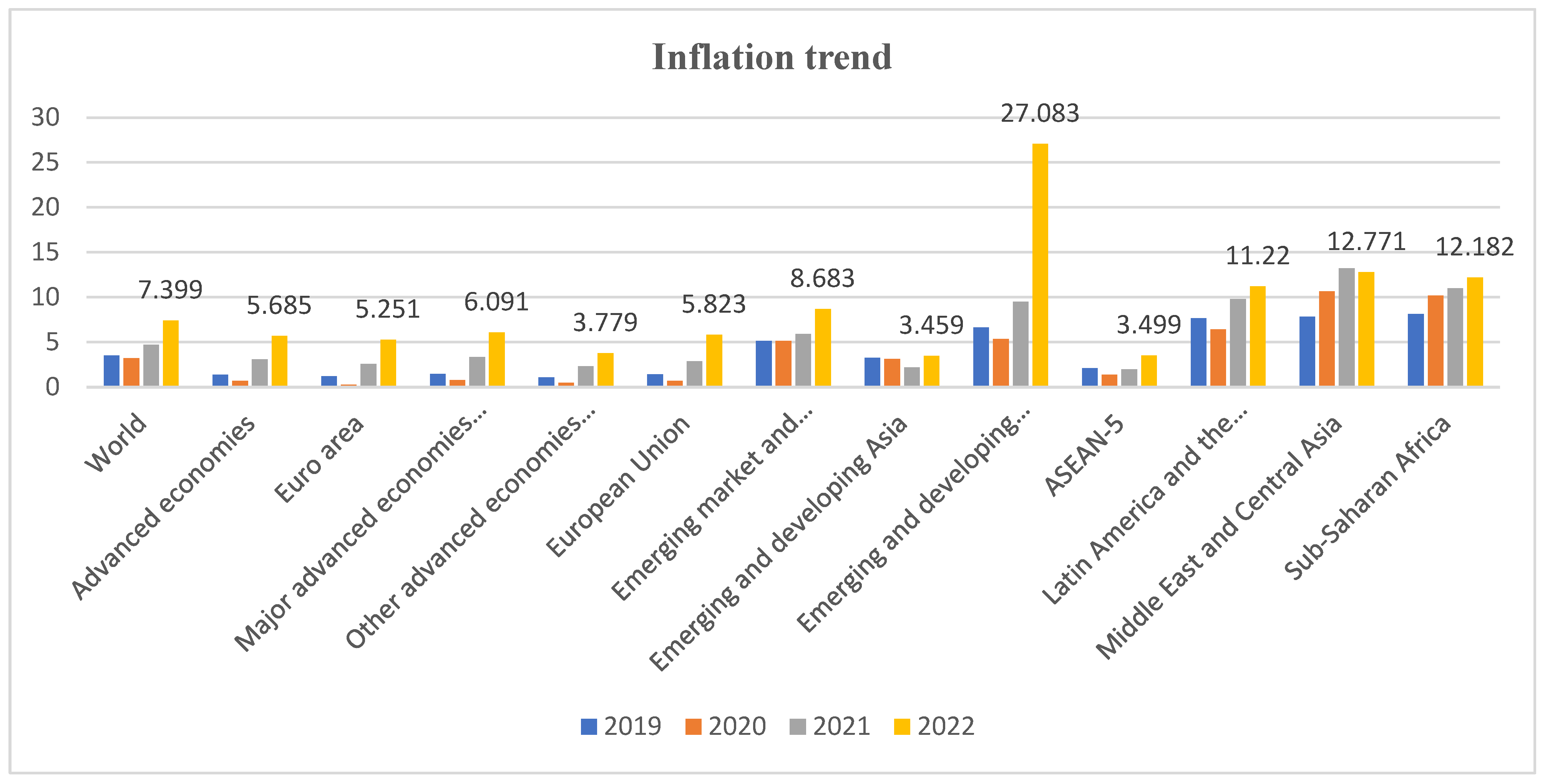

As seen in

Figure 3, the inflation rate in the world reaches the highest percentage registering 7.4 percent in the year 2022

[15]. It seems that inflation is highly increased in all continents of the world. The IMF data report implies that the emerging and developing countries of Europe registered the highest and worst inflation rate increment in 2022 with a 27 percent inflation rate. Sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East, and Central Asia, as well as Latin America and the Caribbean, emerging markets, and developing economies, also registered the highest rate of inflation. The increment level of inflation in 2022 is suppressed compared to other years during the COVID-19 era. Even in 2020, the economic performance of the entire world declined and the inflation rate was not as high as in 2022. This result implies how the Russia–Ukraine war contributed a significant effect to the rise in inflation in Europe and the rest of the world. The war-induced commodity price increases and broadening price pressures have led to the 2022 inflation increment. So far, some European countries and the rest of the world have used monetary policy measures to address inflationary pressures. Policymakers across the region have reacted decisively by tightening monetary policy and implementing measures to soften the blow of higher food and energy prices on the most vulnerable—thus mitigating the risks of social unrest. However, the crisis is still unrest.

Figure 3. Inflation trend over time for all continents. Source: IMF 2022.

In general, the Forex reserve level has multiple implications throughout the crisis. As evidenced in 2022, the advanced economies, major advanced economies, and other advanced economies have declined the level of Forex reserves compared to the preceding years of 2020 and 2021. However, emerging economies, the Middle East and Central Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa have increased the level of forex reserves compared to the preceding years of 2020 and 2021. It is believed that an increase in forex reserves increases the pressure on foreign exchange resulting in financial regulation and controlling difficulties. Therefore, for advanced economies, those currencies trading USD and EUR, increasing the level of forex reserves creates unnecessary currency competition. This scenario has been observed practically in most developing economies as USD became stronger than ever compared to their domestic currencies. As the majority of foreign trades are transacted by USD, the value of it became strong across the globe. However, this scenario forces different countries to look for alternatives as Russia has by setting the RUB as the world trading currency with Russian partners.

It was surprisingly observed that the level of government debt in 2022 for the majority of African, Asian, and Middle Eastern countries increased at the highest rate compared to the preceding years of 2020 and 2021. The governments and policymakers were forced to increase the level of government debt as they have no alternative strategy to fight the impact of COVID-19 by providing vaccinations, food for the poor during the crisis, and providing direct support to different sectors of the economy to boost the performance. Apart from the COVID-19 crisis, the Russia–Ukraine war has badly affected the continents by distorting the prices of food and energy across the world, which indirectly increases the cost of imports. The data from the IMF show that in countries such as Cape Verde, Ghana, Namibia, Sri Lanka, and Brunei government debts hit a peak and they almost became equal to the gross domestic products of the countries or, in some of them, were greater. This could be a dangerous signal for all countries, especially for those countries with the highest government debts. If current debt trends in some countries continue, increasing the public-debt burden means higher interest costs, which divert resources from education, health care, and infrastructure. Apart from that, an increase in government debt decreases the international reputation of the countries and decreases the inward foreign direct investment, increases domestic capital flight, and creates instability in the exchange rate. These economic factors have a direct effect on the society’s cost of living, unemployment, and tax structure that leads governments and policymakers to think about measurement through fiscal and monetary policies. The reaction of considering these two policies to correct economic performance will shift economic crises into political crises and create unrest crises in the countries. More specifically, policy correction was serious during this economic crisis. For example, in Asian and Middle Eastern countries, it was reported that the region had faced some economic challenges when fighting pandemic waves with weak vaccination progress that resulted in rising inflation, which has contributed to declining monetary policy space and added to the difficulties posed by limited fiscal policy space.

Short-Term Risks

Risk of stagflation: Stagflation can be defined in different ways under different scenarios. However, the main idea of stagflation is to describe the economy that has slow growth with relatively high unemployment, which is at the same time accompanied by rising prices (i.e., inflation)

[17]. Stagflation can alternatively be defined as a period of inflation combined with a decline in the gross domestic product (GDP). As observed from the data provided by IMF, there could still be an estimated rate of decline in gross domestic product and an increase in inflation rates across the world. The combination of these two variables will put the world at a short-term risk of stagflation. The risk of stagflation can lead policymakers to think about share economies instead of wage economies as the share economies significantly improve the unemployment–inflation tradeoff (stagflation). However, it also argued that the widespread introduction of share contracts is unlikely to improve macroeconomic performance.

Risk of interest rate: The other disadvantage of the crisis is the raising levels of interest rates. An increased inflation rate directly affects the levels of interest rates. Most emerging and developing countries have corrected their level of interest to control the market. The Hungarian National Bank corrected the interest rate at the beginning of July 2022 by increasing the interest rate from 7.75 to 9.75 percent, the Bank of Canada increased by 1 percent, and the banks of Korea and New Zealand corrected the interest rate by 0.5 percent. The aim of raising interest rates is to slow down the economy by making borrowing more expensive

[18]. In turn, consumers, investors, and businesses are limited in investing

[19], which result in a decrease in the money supply on the market. Furthermore, raising interest rates increase interest expenses for borrowers

[20]. Hence, the willingness to borrow will decrease. However, a decrease in borrowing will make an investment and businesses pause and rise in the unemployment rate

[21]. Additionally, raising interest rates causes the export to be less competitive and makes imports cheaper. The government cost of debt will raise immediately. Using this policy is only recommendable for those countries highly dependent on imports

[22]. Apart from interest rate increments, some countries such as the United Kingdom followed different strategies to tackle the impact of the crisis. They decided to manage through cash transfers. The transferred cash decided to distribute directly to the society based on installment payments. The effectiveness of both strategies is yet to seen based on the market response to the crisis.

The volatility of the exchange rate: One of the most surprising issues during the crisis was the reaction of local currencies to USD across the globe. Changes in economic policies related to interest rates and inflation created an immediate response to the exchange rate

[23]. During the crisis, especially after the beginning of the Russia–Ukraine war, the response of local currencies in developing economies was immediate. The reason for the volatility in the dollar/local currency exchange rates is the fluctuation in the volume of exports, fluctuation of the interest rates, fluctuation in the inflation rate, and so on

[24]. As the western partners, including the USA, put sanctions on Russia for not trading with her; some European countries shifted their face to the USA as a trading partner. As a result, on 11 July 2022, the USD level became equal to the EUR for the first time in 20 years. The INR, IDR, and HUF registered at historic exchange rate levels. The fluctuation of the exchange rate is seemingly happening in microseconds across the globe with the highest rate of variation. The USD is getting stronger than ever compared to other currencies as it is used as a world trading currency. However, countries such as China, Russia, and India are putting pressure on the USD by introducing their local currency as international trading currencies. This could create another alternative for different countries to manage the volatility of their domestic currency against the USD by creating a portfolio as Israel has done. Besides, the volatility of the exchange rate creates additional pressure on the domestic inflation rate by importing aboard inflation

[25]. This scenario is highly observed in those countries mainly dependent on imports, as the consumers are forced to pay the highest price for the same commodity sold for the lowest price in another country.

Rising energy prices: The protracted war in Ukraine and the sanctions imposed on Russia by the European Union have led to a dramatic increase in energy prices across Europe, which has caused an energy crisis in a large part of the continent. Different reports such as vg.hu show that the electricity prices in Europe have risen 515 percent in just over a year, while gas prices have increased 650 percent in the same period through early July. The explosion of energy prices due to the war not only led to a drastic increase in inflation, but also to enormous uncertainty, which has a significant negative impact on foreign exchange rates.

Long-Term Strategic Challenges

Sustainable development goals and green aspects: The three pillars (economic, environmental, and social) of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) represent the most ambitious development agenda ever, setting the vision, framework, and targets for the transition to a sustainable and resilient society. The global socioeconomic and financial systems face unprecedented challenges because of climate change and environmental deterioration

[26]. The existing modes of production and consumption lead to unsustainable levels of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions as well as other environmental consequences that go beyond what the ecosystems can absorb and recycle

[27]. As the clock is running, with just over a decade left to achieve the SDGs, a major push is needed to achieve the sustainable development goals.

Climate finance has emerged as one of the greatest toolkits to overcome the issue

[28]. A key focus is on putting in place new mechanisms at global, regional and country levels to increase climate finance. Countries emerged to devote some part of their budget to green investments after the 2015 Paris agreement. Since that, there has been progress regarding the financing of green projects. However, as a result of the COVID-19 outbreak, the financing level for green investment decreased by 25 percent in 2019

[29]. This number slowly increased to a huge amount of the green finance gap

[30]. According to a recent 2021 report published by

[31], the current investments in green projects found not enough to achieve the objective of sustainable development goals of green aspects, and a USD 133 billion financing gap is expected by 2030 and a 4.1 trillion financing gap is expected by 2050. It calls on all stakeholders to enhance the level of green finance for green investments. However, the current geopolitical and COVID-19 crisis seems major concern in the transition to low-carbon energy. Therefore, how do countries obtain sufficient finances to fill the required green investment? Do country leaders prioritize financing green aspects by putting aside the economic crisis? Does the current economic activity respond to the planned target positively? This is the main question of the era. Hence, the impact of COVID-19 and geopolitics create long-term strategic challenges for green aspects.

Risk of Hyperinflation: Accumulated stagflation has the capability of leading the economy to hyperinflation. Hyperinflation can happen when the prices of goods and services rapidly increase and become out of control

[32]. Theoretically, the economic pieces of the literature suggest an inflation rate that hits 50 percent for continuous years could be considered hyperinflation. Based on this fact, it has been observed in emerging and developing countries of Europe implies a risk of hyperinflation. The region has registered negative economic performances and the highest rates of inflation of any continent in the world. If the current Russia–Ukraine war keeps going, the political crisis of the region can have a different shape as interventions from different countries are expected; this could raise the level of economic crises even more as most of both Russia and Ukraine’s trading partners are in the European region. The extended time of conflict will lead to a decline in productivity and create unexpected pay rises for several goods and services. By accounting for this scenario, it is a decisive time for policymakers to develop new strategies that could tackle the problem. Stopping the war would be the immediate solution to human, economic, and social crises; however, in the long run, alternative strategies should be developed for the countries in this region to lift them from dependence on Russia and Ukraine.

Risk of economic recession: The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and geopolitical crisis are likely to have a profound impact on economic productivity. As the crises continue, there is the possibility of a slowdown in general economic activities especially in emerging and developing European countries as observed in 2022. This situation is likely to force governments to increase the level of government debt to inject the economy, resulting in a higher inflation rate, creating many unbalanced macro-economic variables and providing signs of economic recessions. These could lead consumers to spend less, which means businesses earn less. In response, they produce less and cut wages or lay off workers. This can lead cash-strapped consumers to spend even less, so the recession feeds on itself. At the same time, the level of inflation will hit high as a result of a shortage of goods and services. The policymakers should investigate the current economic scenario of their countries to avoid economic recession. Necessary measurements policies shall take on time by using both fiscal and monetary policy economic toolkits.