Virtual autopsies (VAs) are non-invasive, bypassing many of the challenges posed by traditional autopsies (TAs). One of the main methods for post mortem (PM) imaging is the use of X-ray images, a technique that has been used for a relatively long time now. PM X-ray images allow clear visualisation of fractures and radio-opaque foreign bodies within the deceased, and in this way are useful in guiding TAs in certain circumstances, for example in traumatic deaths. This imaging can also limit the TA, perhaps by providing information that would be difficult to access during the invasive examination, such as fractures in areas like the base of the skull which would require extensive, time-consuming, and delicate dissection.

1. Introduction

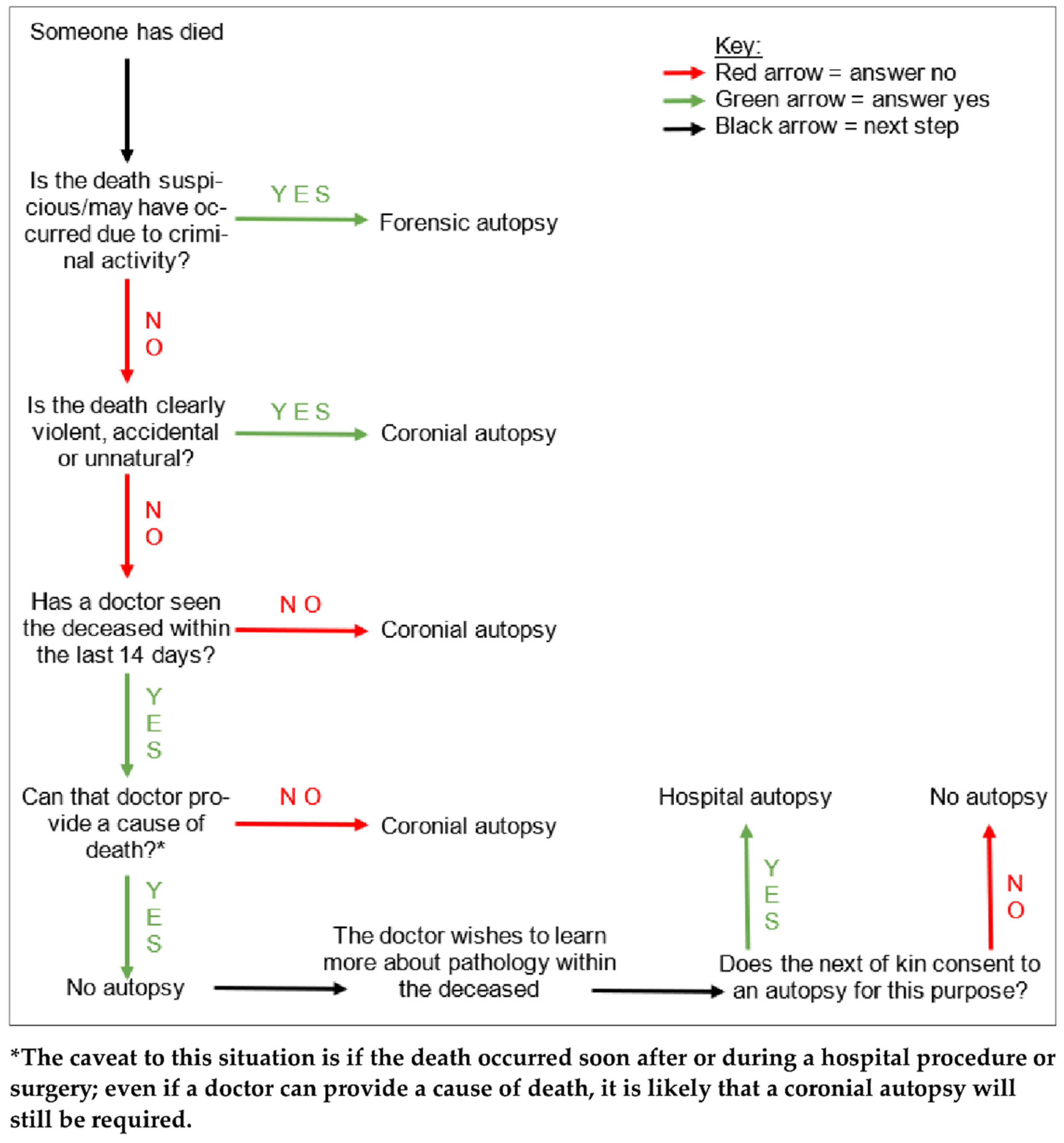

Autopsies are the examinations of deceased patients which are performed in order to determine the cause of death. As outlined in

Figure 1, autopsies in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland are carried out for three main reasons. Firstly, if the cause of death has been clinically certified, but the attending doctor to the deceased has obtained consent from the next of kin, an autopsy may be performed in order to learn more about the pathology (hospital autopsy). Secondly, if there is no clinician involved in the care of the deceased who can certify the cause of death, but the death is not suspicious, the Coroner may order an examination (coronial autopsy). Thirdly, if the death was suspicious or potentially due to criminal activity, it may involve both a police investigation as well as coronial interest, and a more thorough autopsy would be performed in order to find the cause of death, and to gain evidence to present in a court of law (forensic autopsy)

[1].

Figure 1. A tree diagram demonstrating the simplified general decision pathway undertaken when ascertaining whether an autopsy is required, and if so, what type. There are various caveats to these conditions but this diagram provides a general overview.

Traditional autopsies (TAs) are invasive procedures, typically involving an external examination of the body, and an examination of the internal organs which are obtained by evisceration of the thorax, abdomen, and skull. This is coupled with a report surrounding the circumstances of the death, provided by the Coroner’s office, as well as the medical history of the deceased. If the cause of death cannot be found through macroscopic examination of the viscera, samples may have to be retained for further histological, toxicological, biochemical, and/or microbiological analysis.

It is worth noting that coronial autopsies do not require informed consent from the deceased’s next of kin in order to take place. However, the family and friends of the deceased may be able to negotiate a limited TA on the basis of certain lesions within the body. For example, if a clear cause of death has already been found upon thoracoabdominal examination, the head and skull may not need to be opened in order to examine the brain. In general though, if the next of kin object to an autopsy taking place on whatever grounds, this will not affect the Coroner’s decision for one to be performed.

Due to a variety of reasons surrounding the challenges and disadvantages of TAs, the use of radiological imaging for non-invasive examinations, or virtual autopsies (VAs), is gaining traction. Most commonly, post mortem (PM) computed tomography (PMCT) and PM magnetic resonance (PMMR) are being used in various applications to garner more information surrounding the cause of death. VAs also increase the use of non-invasive and minimally invasive examination techniques available to pathologists, thereby reducing the necessity to fully open the body in order to perform an autopsy

[2]. As radiological technology advances, the idea of using VA techniques as a substitute, rather than just an adjunct, for TA is gaining popularity.

2. General Overview of Imaging in Autopsy

One of the main methods for PM imaging is the use of X-ray images, a technique that has been used for a relatively long time now

[3]. PM X-ray images allow clear visualisation of fractures and radio-opaque foreign bodies within the deceased, and in this way are useful in guiding TAs in certain circumstances, for example in traumatic deaths. This imaging can also limit the TA, perhaps by providing information that would be difficult to access during the invasive examination, such as fractures in areas like the base of the skull which would require extensive, time-consuming, and delicate dissection. Another benefit for taking X-ray images is the portability and speed. However, a pitfall for this imaging method is its two-dimensional quality; to gain any appreciation of structures in a three-dimensional state, multiple X-ray images must be obtained, often through laborious manoeuvring and balancing of the body into many different positions for each image

[3]. This is a tedious process and in terms of coronial investigations, its usage is limited to specific circumstances and deaths.

2.1. PMCT

As such, the evolution of more modern, three-dimensional clinical imaging techniques has taken place, and these imaging methods have emerged into PM investigations, instead of being used only with living patients. The current availability of imaging methods for VA are largely PMCT techniques. Full body PMCT scanning is growing in usage for coronial autopsies, for example where there are large Muslim or Jewish communities

[4]. PMCT is also available privately in Wales and the South of England for families who wish to avoid a TA for their loved ones

[4]. The cost of a private PMCT for the next of kin in these areas is quoted as £500–£1500

[5][6][7].

2.2. PMMR

Whilst PMCT techniques are currently at the forefront of VA in England and Wales, PMMR methods are also available. The difference in the use of current VA methods may explain the disparity in the amount of studies reported on PMCT and PMMR; namely, there is a lot more literature on the former than the latter. Practically, there are many areas in which PMCT is superior to PMMR. PMCT is both cheaper and faster to perform than PMMR, with a PMCT taking around five to ten minutes to perform in comparison to the approximate hour taken for PMMR

[8][9][10]. PMCT is also more widely available across England and Wales; together, these may be the main reasons for the currently more frequent use of PMCT over PMMR

[4][9][11][12]. However, one advantage of PMMR over PMCT is that MRI scanning does not use radiation in order to acquire images

[13], rendering it a safer VA technique for mortuary technicians, who tend to be the team members who manoeuvre the bodies in and out of the scanners. On the other hand, one issue posed by the use of PMMR is metal artefacts within the body; the presence of metal can not only distort the images on the scan, but may even disrupt the body if ripped out by the strong magnetic fields used to image

[14].

2.3. Overview of the VA Procedure

Typically, the current method for VA is to perform a full-body scan; this would be undertaken alongside an external examination of the body by a pathologist. As with TA, this is in conjunction with scrutiny of the Coroner’s office report detailing the circumstances surrounding the death, as well as the medical records of the deceased

[15]. The imaging would then be interpreted by a radiologist, who then offers either a cause of death to the pathologist, or a recommendation for TA; a TA would be recommended in the instance that the scan is inconclusive regarding cause of death, or when there is a degree of uncertainty regarding any significant lesions on VA. The radiologist’s report will be considered by the pathologist, who will either proceed with a TA anyway, or complete the cause of death form on the basis of the lesions seen at VA and the opinion of the radiologist.

2.4. VA vs. TA

There are many advantages of VA over TA. The images obtained through VA serve as a permanent record of the autopsy, unlike during TA, where the body goes on to be destroyed by cremation or decomposition in burial without any evidence of the lesions except in the pathologist’s report. Not only would the records of VA enable pathologists to more readily seek second opinions, but they would also allow more scrutiny of autopsies, which could help to improve the quality of autopsy reports being produced by pathologists

[16][17][18].

Further, nearly 40% of all deaths being reported to the Coroner in England and Wales require an autopsy

[19]; the increased speed of an accurate VA in comparison to TA has the potential to help with the management of this huge workload for the mortuary and pathologist. This could also improve turnaround times to release the body, a positive for the loved ones of the deceased, but also regarding mortuary storage capacity

[20]. This time-saving and service expansion is also of importance considering the current shortage of pathologists across England and Wales who are willing to perform TAs

[21]. Indeed, perhaps the emergence of non-invasive investigations would encourage more pathologists to continue performing PM investigations instead of choosing to opt out.

Lastly, another advantage of VA over TA is the lack of physical contact involved with the body, since the scans are performed with the deceased remaining zipped in a body-bag. As aforementioned, this proved to be essential during the COVID-19 pandemic, in order to reduce the risk of the SARS-CoV-2 virus infecting mortuary staff and pathologists; the transmission of bloodborne and airborne diseases would be reduced by a lower number of TAs. Further, this practice contains any entomological infestations of a decomposing corpse within the body-bag, reducing the risk of infestation spreading to other bodies as well as within the mortuary itself, particularly during the hot summer months. A non-invasive autopsy also means that fewer sharp instruments are used, reducing the risk of needlestick injuries for mortuary staff and pathologists, as well as further transmission of bloodborne diseases

[22].

However, there is a caveat: these advantages of VA can only be achieved through accurate diagnoses. If a VA is performed and no cause of death can be found, the TA may have to be performed anyway. This combination of TA following VA would result in an invasive examination regardless, as well as prolonged turnaround times in comparison to TA alone, not to mention the cost of both autopsies instead of one. As such, the accuracy and effectiveness of VA techniques must be optimised in order to justify using VA as a first-line investigation into the cause of death, as well as the financial and spatial investments in setting up such services.

Finally, it is an unfortunate fact that not every mortuary, particularly public mortuaries which are not part of a hospital, has the space or funding to realistically consider on-site installation of VA scanning facilities. This would mean transferring bodies to other facilities in order to perform scanning, which is timely and costly. If mortuaries do have scanners on site, they may have to share the usage with scans for living patients; this juggling could mean longer waiting times for autopsies to take place, depending on how busy the hospital is.

3. Conclusion

PMCT and PMMR each have individual strengths and weaknesses, in practical, financial, and imaging terms. VA can provide detailed, non-invasive information about the whole body, although for truly thorough imaging, at present, one method would not be sufficient to adequately analyse all areas. There are still flaws in the ability of VA to detect very common causes of death when used in general coronial investigations. As such, VA is currently a useful adjunct or preliminary investigation method to TA, but not a replacement just yet; the usefulness of VA seems to depend on the circumstances and pathologies surrounding the death. However, together, VA and TA may be able to achieve a more complete and thorough autopsy than either method alone.