| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Camila Xu | -- | 2845 | 2022-11-07 01:52:05 |

Video Upload Options

Earwax, also known by the medical term cerumen, is a brown, orange, red, yellowish or gray waxy substance secreted in the ear canal of humans and other mammals. It protects the skin of the human ear canal, assists in cleaning and lubrication, and provides protection against bacteria, fungi, and water. Earwax consists of dead skin cells, hair, and the secretions of cerumen by the ceruminous and sebaceous glands of the outer ear canal. Major components of earwax are long chain fatty acids, both saturated and unsaturated, alcohols, squalene, and cholesterol. Excess or compacted cerumen is the buildup of ear wax causing a blockage in the ear canal and it can press against the eardrum or block the outside ear canal or hearing aids, potentially causing hearing loss.

1. Physiology

Cerumen is produced in the cartilaginous portion which is the outer third portion of the ear canal. It is a mixture of viscous secretions from sebaceous glands and less-viscous ones from modified apocrine sweat glands.[1] The primary components of earwax are shed layers of skin, with, on average, 60% of the earwax consisting of keratin, 12–20% saturated and unsaturated long-chain fatty acids, alcohols, squalene and 6–9% cholesterol.[2]

1.1. Wet or Dry

There are two distinct genetically determined types of earwax: the wet type, which is dominant, and the dry type, which is recessive. East Asians, Southeast Asians and Native Americans are more likely to have the dry type of earwax (gray and flaky), while African and European people are more likely to have wet type earwax (honey-brown, dark orange to dark-brown and moist).[3] 30-50% of South Asians, Central Asians and Pacific Islanders have the dry type of cerumen.[4] Cerumen type has been used by anthropologists to track human migratory patterns, such as those of the Inuit.[5] In Japan, wet-type earwax is more prevalent among the Ainu, in contrast to the Yamato majority.[6] The wet type earwax differs biochemically from the dry type mainly by its higher concentration of lipid and pigment granules; for example the wet type is 50% lipid while the dry type is only 20%.[2]

A specific gene has been identified that determines whether people have wet or dry earwax.[7] The difference in cerumen type has been tracked to a single base change (a single nucleotide polymorphism) in a gene known as "ATP-binding cassette C11 gene", specifically rs17822931.[8] Dry-type individuals are homozygous for adenine whereas wet-type requires at least one guanine. Wet-type earwax is associated with armpit odor, which is increased by sweat production. Researchers have conjectured that the reduction in sweat or body odor was beneficial to the ancestors of East Asians and Native Americans who are thought to have lived in cold climates.[9][10]

1.2. Cleaning

Cleaning of the ear canal occurs as a result of the "conveyor belt" process of epithelial migration, aided by jaw movement.[11] Cells formed in the centre of the tympanic membrane migrate outwards from the umbo (at a rate comparable to that of fingernail growth) to the walls of the ear canal, and move towards the entrance of the ear canal. The cerumen in the ear canal is also carried outwards, taking with it any particulate matter that may have gathered in the canal. Jaw movement assists this process by dislodging debris attached to the walls of the ear canal, increasing the likelihood of its expulsion.

Removing earwax is in the scope of practice for audiologists and otorhinolaryngologists (ear, nose, and throat) doctors.

1.3. Lubrication

The lubrication provided by cerumen prevents desiccation of the skin within the ear canal. The lubricative properties arise from the high lipid content of the sebum produced by the sebaceous glands. In wet-type cerumen, these lipids include cholesterol, squalene, and many long-chain fatty acids and alcohols.[12][13]

1.4. Antimicrobial Effects

While studies conducted up until the 1960s found little evidence supporting antibacterial activity for cerumen,[14] more recent studies have found that cerumen has a bactericidal effect on some strains of bacteria. Cerumen has been found to reduce the viability of a wide range of bacteria, including Haemophilus influenzae, Staphylococcus aureus, and many variants of Escherichia coli, sometimes by as much as 99%.[15][16] The growth of two fungi commonly present in otomycosis was also significantly inhibited by human cerumen.[17] These antimicrobial properties are due principally to the presence of saturated fatty acids, lysozyme and, especially, to the slight acidity of cerumen (pH typically around 6.1 in average individuals[18]). Conversely, other research has found that cerumen can support microbial growth and some cerumen samples were found to have bacterial counts as high as 107/g cerumen. The bacteria were predominantly commensals.[19]

2. Excess Earwax (Impacted Cerumen)

Earwax is produced by sebaceous and ceruminous glands in the ear canal,[2] which leads from the outer ear to the eardrum. Earwax helps protect the ear by trapping dust and other foreign particles that could filter through and damage the eardrum.[2] Normally, earwax moves toward the opening of the ear and falls out or is washed away, but some people's ears produce too much wax. This is referred to as excessive earwax or impacted cerumen.[20]

Excessive earwax may impede the passage of sound in the ear canal, causing mild[21] conductive hearing loss, pain in the ear, itchiness, or dizziness. Untreated impacted wax can result in hearing loss, social withdrawal, poor work function and even mild paranoia. People with impacted wax may also present with perforated eardrums; this is usually self-induced as compacted earwax alone cannot perforate the eardrum, though for example the use of earbuds could be responsible.[2] A physical exam usually checks for visibility of the tympanic membrane, which can be blocked by excessive cerumen.

Impacted cerumen may improve on its own, but treatment by a doctor is generally safe and effective. Hearing usually returns completely after the impacted earwax is removed.

Hearing aids may be associated with increased earwax impaction,[22] as they prevent earwax from being removed from the ear canal, thus causing blockage which leads to it being impacted.[2] It is estimated to be the cause of 60–80% of hearing aid faults. Earwax can get into a hearing aid's vents and receivers, and degrades the components inside the hearing aid due to its acidity.[23] Excessive earwax can also cause tinnitus, a constant ringing in the ears,[24] ear fullness, hearing loss and ear pain.[2]

2.1. Treatment

Movement of the jaw helps the ears' natural cleaning process. The American Academy of Otolaryngology discourages earwax removal, unless the excess earwax is symptomatic.[25]

While a number of methods of earwax removal are effective, their comparative merits have not been determined.[26] A number of softeners are effective; however, if this is not sufficient,[26] the most common method of cerumen removal is syringing with warm water.[27] A curette method is more likely to be used by audiologists and otolaryngologists when the ear canal is partially occluded and the material is not adhering to the skin of the ear canal. Cotton swabs, on the other hand, push most of the earwax farther into the ear canal and remove only a small portion of the top layer of wax that happens to adhere to the fibers of the swab.[28]

Softeners

This process is referred to as cerumenolysis. Topical preparations for the removal of earwax may be better than no treatment, and there may not be much difference between types, including water and olive oil.[26][29] However, there were not enough studies to draw firm conclusions, and the evidence on irrigation and manual removal is equivocal.[26]

Commercially or commonly available cerumenolytics include:[30]

- Any of a number of types of oil

- Urea hydrogen peroxide (6.5%) and glycerine

- A solution of sodium bicarbonate in water, or sodium bicarbonate B.P.C. (sodium bicarbonate and glycerine)

- Cerumol (peanut oil, turpentine and dichlorobenzene)

- Cerumenex (triethanolamine, polypeptides and oleate-condensate)

- Docusate, an emulsifying agent, an active ingredient found in laxatives

- Mineral oil

A cerumenolytic should be used 2–3 times daily for 3–5 days prior to the cerumen extraction.[31]

Microsuction

Microsuction involves the use of a vacuum suction probe to break up and extract impacted cerumen. Microsuction can be preferred over other methods as it avoids the presence of moisture in the ear, is often faster than irrigation, and is performed with direct vision of the earwax being removed.[32] Typically, a camera with lights and guide hole is utilised, with a long metal vacuum probe being inserted into the guide hole - the practitioner is then able to see inside the ear and remove earwax under pressure. Potential adverse effects include dizziness, temporary tinnitus, and reduced hearing due to volume of the pump and the proximity of the vacuum probe to the ear drum - the frequency of these are reduced where the cerumen is softened in the five days preceding microsuction. In general, microsuction is well tolerated and even preferred by many patients.[33]

Ear irrigation

Once the cerumen has been softened, it may be removed from the ear canal by irrigation, but the evidence on this practice is equivocal.[26] This may be effectively accomplished with a spray type ear washer, commonly used in the medical setting or at home, with a bulb syringe.[34] Ear syringing techniques are described in great detail by Wilson & Roeser[31] and Blake et al.[35] who advise pulling the external ear up and back, and aiming the nozzle of the syringe slightly upwards and backwards so that the water flows as a cascade along the roof of the canal. The irrigation solution flows out of the canal along its floor, taking wax and debris with it. The solution used to irrigate the ear canal is usually warm water,[35] normal saline,[36] sodium bicarbonate solution,[37] or a solution of water and vinegar to help prevent secondary infection.[35]

Affected people generally prefer the irrigation solution to be warmed to body temperature,[36] as dizziness is a common side effect of ear washing or syringing with fluids that are colder or warmer than body temperature.[27][35]

Curette and cotton swabs

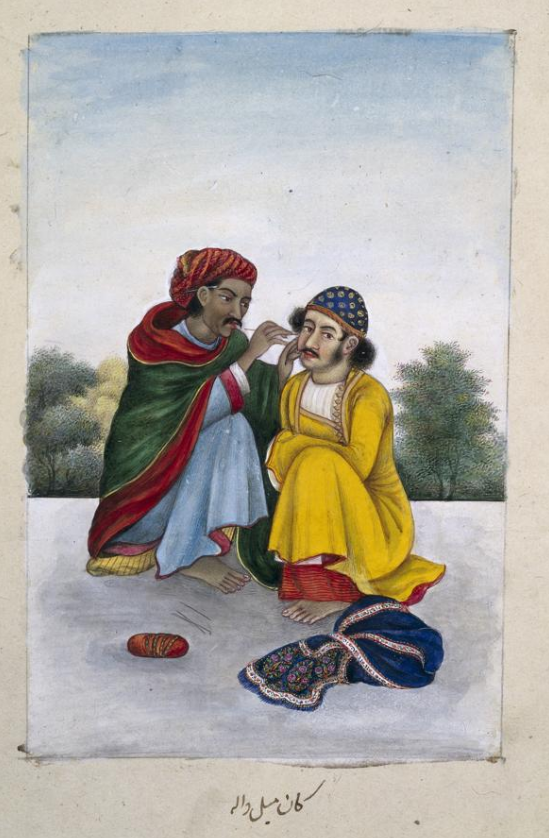

Earwax can be removed with an ear pick/curette, which physically dislodges the earwax and scoops it out of the ear canal.[38] In the West, use of ear picks is usually only done by health professionals. Curetting earwax using an ear pick was common in ancient Europe and is still practised in East Asia. Since the earwax of most Asians is of the dry type,[3] it is extremely easily removed by light scraping with an ear pick, as it simply falls out in large pieces or dry flakes.

It is generally advised not to use cotton swabs (Q-Tips or cotton buds), as doing so will likely push the wax farther down the ear canal, and if used carelessly, perforate the eardrum.[28] Abrasion of the ear canal, particularly after water has entered from swimming or bathing, can lead to ear infection. Also, the cotton head may fall off and become lodged in the ear canal. Therefore, cotton swabs should be used only to clean the external ear.

Ear candles and vacuuming

Ear candling, also called ear coning or thermal-auricular therapy, is an alternative medicine practice claimed to improve general health and well-being by lighting one end of a hollow candle and placing the unlit end in the ear canal. It, however, is not recommended as it is dangerous, ineffective, and counterproductive.[25][39] Advocates say that the dark residue that shows after the procedure consists of extracted earwax, proving the efficacy of the procedure. Studies have shown that the same dark residue is left, whether or not the candle (which is made of cotton fabric and beeswax and leaves a residue after burning) is inserted into an ear. This demonstrates that the waxy residue is derived from the burnt candle wax itself and not the ear.[40] The color of the candle wax matches the light brown-colored wax of the human ear, making the distinction between the two waxes more difficult for a layperson. Because the candle itself is a hollow tube, some of the hot burnt wax could drop down inside the candle, into the ear canal, potentially injuring the eardrum. The American Academy of Otolaryngology states that ear candles are not a safe option for removing ear wax, and that no controlled studies or scientific evidence support their use for ear wax removal.[41] Survey responses from medical specialists (otolaryngologists) in the United Kingdom reported ear injuries from ear candling including; burns, ear canal occlusions and ear drum perforations and secondary ear canal infections with temporary hearing loss.[39] The Food and Drug Administration has successfully taken several regulatory actions against the sale and distribution of ear candles since 1996, including seizing ear candle products and ordering injunctions. They are now marked as "providing no health benefit".[41]

Home "ear vacs" were ineffective at removing ear-wax, especially when compared to a Jobson-Horne probe.[42]

Potential complications

A postal survey of British general practitioners[27] found that only 19% always performed cerumen removal themselves. It is problematic as the removal of cerumen is not without risk, and physicians and nurses often have inadequate training for removal. Irrigation can be performed at home with proper equipment as long as the person is careful not to irrigate too hard. All other methods should be carried out only by individuals who have been sufficiently trained in the procedure.

The author Bull advised physicians: "After removal of wax, inspect thoroughly to make sure none remains. This advice might seem superfluous, but is frequently ignored."[37] This was confirmed by Sharp et al.,[27] who, in a survey of 320 general practitioners, found that only 68% of doctors inspected the ear canal after syringing to check that the wax was removed. As a result, failure to remove the wax from the canal made up approximately 30% of the complications associated with the procedure. Other complications included otitis externa (swimmer's ear), which involves inflammation or bacterial infection of the external acoustic meatus, as well as pain, vertigo, tinnitus, and perforation of the ear drum. Based on this study, a rate of major complications in 1/1000 ears syringed was suggested.[27]

Claims arising from ear syringing mishaps account for about 25% of the total claims received by New Zealand's Accident Compensation Corporation ENT Medical Misadventure Committee.[35] While high, this is not surprising, as ear syringing is an extremely common procedure. Grossan suggested that approximately 150,000 ears are irrigated each week in the United States, and about 40,000 per week in the United Kingdom.[43] Extrapolating from data obtained in Edinburgh, Sharp et al.[27] place this figure much higher, estimating that approximately 7000 ears are syringed per 100,000 population per annum. In the New Zealand claims mentioned above, perforation of the tympanic membrane was by far the most common injury resulting in significant disability.

2.2. Prevalence

The prevalence of impacted earwax is different across the world.

In the United Kingdom 2 to 6% of the population have cerumen that is impacted. In America 3.6% of emergency visits caused by ear issues were due to impacted cerumen. In Brazil 8.4–13.7% of the population have impacted cerumen.[44]

3. History

The treatment of excess ear wax was described by Aulus Cornelius Celsus in De Medicina in the 1st century:[45]

When a man is becoming dull of hearing, which happens most often after prolonged headaches, in the first place, the ear itself should be inspected: for there will be found either a crust such as comes upon the surface of ulcerations, or concretions of wax. If a crust, hot oil is poured in, or verdigris mixed with honey or leek juice or a little soda in honey wine. And when the crust has been separated from the ulceration, the ear is irrigated with tepid water, to make it easier for the crusts now disengaged to be withdrawn by the ear scoop. If it is wax, and if it is soft, it can be extracted in the same way by the ear scoop; but if hard, vinegar containing a little soda[46] is introduced; and when the wax has softened, the ear is washed out and cleared as above. ... Further, the ear should be syringed with castoreum mixed with vinegar and laurel oil and the juice of young radish rind, or with cucumber juice, mixed with crushed rose leaves. The dropping in of the juice of unripe grapes mixed with rose oil is also fairly efficacious against deafness.

3.1. Uses

- In medieval times, earwax and other substances such as urine were used to prepare pigments used by scribes to illustrate illuminated manuscripts.[47]

- Pliny the Elder, in his Natural History, wrote that earwax—when applied topically—cured bites from humans, scorpions, and serpents; it was said to work best when taken from the ears of the wounded person itself.[48]

- The first lip balm may have been based on earwax.[49] The 1832 edition of the American Frugal Housewife said that "nothing was better than earwax to prevent the painful effects resulting from a wound by a nail [or] skewer"; and also recommended earwax as a remedy for cracked lips.[50]

- Before waxed thread was commonly available, a seamstress would use her own earwax to stop the cut ends of threads from fraying.[51]

References

- "Anatomy and orientation of the human external ear". Journal of the American Academy of Audiology 8 (6): 383–90. December 1997. PMID 9433684. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9433684

- "Impacted cerumen: composition, production, epidemiology and management". QJM 97 (8): 477–88. August 2004. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hch082. PMID 15256605. https://dx.doi.org/10.1093%2Fqjmed%2Fhch082

- Overfield, Theresa (1985). Biologic variation in health and illness: race, age, and sex differences. Menlo Park, Calif: Addison-Wesley, Nursing Division. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-201-12810-9. https://archive.org/details/biologicvariatio0000over/page/46. "... most common type in Whites and Blacks is dark brown and moist. Dry wax, most common in Orientals and Native Americans, is gray and dry. It is flaky and may form a thin mass that lies in the ear canal."

- "The science of stinky sweat and earwax". 2015-04-14. http://www.abc.net.au/science/articles/2015/04/14/4213402.htm.

- "Cerumen types in Eskimos". American Journal of Physical Anthropology 47 (2): 209–10. September 1977. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330470203. PMID 910884. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002%2Fajpa.1330470203

- "Miscellaneous musings on the Ainu, I". Ahnenkult.com. http://www.ahnenkult.com/?p=746.

- Diep, Francie (2014-02-13). "The Scent Of Your Earwax May Yield Valuable Information | Popular Science". Popsci.com. http://www.popsci.com/article/science/scent-your-earwax-may-yield-valuable-information?src=SOC&dom=fb.

- Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) 117800 https://omim.org/entry/117800

- "A SNP in the ABCC11 gene is the determinant of human earwax type". Nature Genetics 38 (3): 324–30. March 2006. doi:10.1038/ng1733. PMID 16444273. http://kumel.medlib.dsmc.or.kr/handle/2015.oak/33472.

- Nakano, Motoi, Nobutomo Miwa, Akiyoshi Hirano, Koh-ichiro Yoshiura, and Norio Niikawa. "A strong association of axillary osmidrosis with the wet earwax type determined by genotyping of the ABCC11 gene." BMC genetics 10, no. 1 (2009): 42.

- "Epithelial Migration on the Tympanic Membrane". The Journal of Laryngology and Otology 78 (9): 808–30. September 1964. doi:10.1017/s0022215100062800. PMID 14205963. https://dx.doi.org/10.1017%2Fs0022215100062800

- "Identification of long-chain fatty acids and alcohols from human cerumen by the use of picolinyl and nicotinate esters". Biomedical & Environmental Mass Spectrometry 18 (9): 719–23. September 1989. doi:10.1002/bms.1200180912. PMID 2790258. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002%2Fbms.1200180912

- "Composition of cerumen lipids". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 23 (5 Pt 1): 845–9. November 1990. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(90)70301-W. PMID 2254469. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2F0190-9622%2890%2970301-W

- "Studies on the growth of bacteria in the human ear canal". The Journal of Investigative Dermatology 27 (3): 165–70. September 1956. doi:10.1038/jid.1956.22. PMID 13367525. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038%2Fjid.1956.22

- "Bactericidal activity of cerumen". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 18 (4): 638–41. October 1980. doi:10.1128/aac.18.4.638. PMID 7447422. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=284062

- "Bactericidal activity of wet cerumen". The Annals of Otology, Rhinology, and Laryngology 93 (2 Pt 1): 183–6. 1984. doi:10.1177/000348948409300217. PMID 6370076. https://dx.doi.org/10.1177%2F000348948409300217

- "The activity against yeasts of human cerumen". The Journal of Laryngology and Otology 102 (8): 671–2. August 1988. doi:10.1017/s0022215100106115. PMID 3047287. https://dx.doi.org/10.1017%2Fs0022215100106115

- "Disorders of the external auditory canal". Journal of the American Academy of Audiology 8 (6): 367–78. December 1997. PMID 9433682. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9433682

- "Study of common aerobic flora of human cerumen". The Journal of Laryngology and Otology 112 (7): 613–6. July 1998. doi:10.1017/s002221510014126x. PMID 9775288. https://dx.doi.org/10.1017%2Fs002221510014126x

- "A to Z: Impacted Cerumen (for Parents) - Nemours". https://kidshealth.org/Nemours/en/parents/az-impacted-cerumen.html.

- "Hearing loss in preschool children from a low income South African community". International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology 115: 145–148. December 2018. doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2018.09.032. PMID 30368375. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.ijporl.2018.09.032

- Chou, R.; Dana, T.; Bougatsos, C.; Fleming, C.; Beil, T. (March 2011). Screening for Hearing Loss in Adults Ages 50 Years and Older: A Review of the Evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). PMID 21542547. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0009751/. Retrieved 5 July 2013.

- "The active earcanal". Journal of the American Academy of Audiology 8 (6): 401–10. December 1997. PMID 9433686. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9433686

- Aleccia, JoNel (August 29, 2018). "The Dangers of Excessive Earwax". https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-dangers-of-excessive-earwax/.

- "Clinical Practice Guideline (Update): Earwax (Cerumen Impaction) Executive Summary". Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery 156 (1): 14–29. January 2017. doi:10.1177/0194599816678832. PMID 28045632. https://dx.doi.org/10.1177%2F0194599816678832

- "The safety and effectiveness of different methods of earwax removal: a systematic review and economic evaluation". Health Technology Assessment 14 (28): 1–192. June 2010. doi:10.3310/hta14280. PMID 20546687. https://dx.doi.org/10.3310%2Fhta14280

- "Ear wax removal: a survey of current practice". BMJ 301 (6763): 1251–3. December 1990. doi:10.1136/bmj.301.6763.1251. PMID 2271824. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1664378

- "Ear wax". Tchain.com. http://www.tchain.com/otoneurology/disorders/hearing/wax2.html.

- "Ear drops for the removal of ear wax". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 7: CD012171. July 2018. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012171.pub2. PMID 30043448. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=6492540

- "The efficacy of wax solvents: in vitro studies and a clinical trial". The Journal of Laryngology and Otology 84 (10): 1055–64. October 1970. doi:10.1017/s0022215100072856. PMID 5476901. https://dx.doi.org/10.1017%2Fs0022215100072856

- "Cerumen management: professional issues and techniques". Journal of the American Academy of Audiology 8 (6): 421–30. December 1997. PMID 9433688. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9433688

- "Treatment of impacted ear wax: a case for increased community-based microsuction". BJGP Open 4 (2). 2020. doi:10.3399/bjgpopen20X101064. https://dx.doi.org/10.3399%2Fbjgpopen20X101064

- "Temporary threshold shift following ear canal microsuction". International Journal of Audiology 59 (9): 713-718. 2020. doi:10.1080/14992027.2020.1746977. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080%2F14992027.2020.1746977

- "Randomized trial of bulb syringes for earwax: impact on health service utilization". Annals of Family Medicine 9 (2): 110–4. 2011. doi:10.1370/afm.1229. PMID 21403136. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3056857

- "When not to syringe an ear". The New Zealand Medical Journal 111 (1077): 422–4. November 1998. PMID 9861921. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9861921

- "Warmed versus room temperature saline solution for ear irrigation: a randomized clinical trial". Annals of Emergency Medicine 34 (3): 347–50. September 1999. doi:10.1016/S0196-0644(99)70129-0. PMID 10459091. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2FS0196-0644%2899%2970129-0

- Bull, P. D. (2002). Lecture notes on diseases of the ear, nose, and throat (6th ed.). Oxford: Blackwell Science. pp. 26–27. ISBN 978-0-632-06506-6.

- Evidences Based Cerumen Removal Protocol http://audiologysupplies.com/blog/cerumen-management-protocol-template

- "Ear candles--efficacy and safety". The Laryngoscope 106 (10): 1226–9. October 1996. doi:10.1097/00005537-199610000-00010. PMID 8849790. https://dx.doi.org/10.1097%2F00005537-199610000-00010

- "Ear Candling: Getting Burned | PeopleHearingBetter". http://phb.secondsensehearing.com/content/ear-candling-getting-burned.

- "Earwax". American Academy of Otolaryngology. http://www.entnet.org/HealthInformation/earwax.cfm.

- "A non-randomized comparison of earwax removal with a 'do-it-yourself' ear vacuum kit and a Jobson-Horne probe". Clinical Otolaryngology 30 (4): 320–3. August 2005. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2273.2005.01020.x. PMID 16209672. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2Fj.1365-2273.2005.01020.x

- "Cerumen removal--current challenges". Ear, Nose, & Throat Journal 77 (7): 541–6, 548. July 1998. doi:10.1177/014556139807700710. PMID 9693470. https://dx.doi.org/10.1177%2F014556139807700710

- "Contributing factors to high prevalence of hearing impairment in the Elias Motsoaledi Local Municipal area, South Africa: A rural perspective". The South African Journal of Communication Disorders = die Suid-Afrikaanse Tydskrif vir Kommunikasieafwykings 66 (1): e1–e7. February 2019. doi:10.4102/sajcd.v66i1.611. PMID 30843412. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=6407449

- Celsus, Aulus Cornelius; W.G. Spencer translation. "Book VI". https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Celsus/6*.html.

- "acetum et cum eo nitri paulum". Nitri is rendered as "soda" here, i.e. soda ash, though the word can refer to a variety of alkaline substances or to sodium nitrate. (http://www.archives.nd.edu/cgi-bin/words.exe?nitri http://www.history-science-technology.com/Notes/Notes%208.htm) Note that acidification of sodium carbonate yields sodium bicarbonate.

- "Iberian manuscripts (pigments)". Web.ceu.hu. http://web.ceu.hu/medstud/manual/MMM/glossary.html.

- "Pliny the Elder, The Natural History, BOOK XXVIII. REMEDIES DERIVED FROM LIVING CREATURES., CHAP. 8.—REMEDIES DERIVED FROM THE WAX OF THE HUMAN EAR.". https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.02.0137:book=28:chapter=8.

- "Human antimicrobial proteins in ear wax". European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases 30 (8): 997–1004. August 2011. doi:10.1007/s10096-011-1185-2. PMID 21298458. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00666674.

- Child, Lydia Maria Francis (1841). The American frugal housewife ... - Google Books. p. 116. https://books.google.com/books?id=D3AEAAAAYAAJ&q=%22The+American+Frugal+Housewife%22&pg=PP1. Retrieved 2010-05-02.

- "Bodkin biographies.". The Materiality of Individuality. New York, NY.: Springer. 2009. pp. 95–108. https://bu.academia.edu/MaryBeaudry/Papers/120776/Bodkin_Biographies.