Video Upload Options

Interslavic (Medžuslovjansky; Меджусловјанскы) is a zonal constructed language based on the Slavic languages. Its purpose is to facilitate communication between representatives of different Slavic nations, as well as to allow people who do not know any Slavic language to communicate with Slavs by being understandable to most, if not all Slavic speakers without them having to learn the language themselves. For Slavs it can fulfill an educational role as well. Interslavic can be classified as a semi-constructed language. It is essentially a modern continuation of Old Church Slavonic, but also draws on the various improvised language forms Slavs have been using for centuries to communicate with Slavs of other nationalities, for example in multi-Slavic environments and on the Internet, providing them with a scientific base. Thus, both grammar and vocabulary are based on the commonalities between the Slavic languages, and non-Slavic elements are avoided. Its main focus lies on instant understandability rather than easy learning, a balance typical for naturalistic (as opposed to schematic) languages. Precursors of Interslavic have a long history and predate constructed languages like Volapük and Esperanto by centuries: the oldest description, written by the Croatian priest Juraj Križanić, goes back to the years 1659–1666. In its current form, Interslavic was created in 2006 under the name Slovianski. In 2011, Slovianski underwent a thorough reform and merged with two other projects, simultaneously changing its name to "Interslavic", a name that was first proposed by the Czech Ignác Hošek in 1908. Interslavic can be written using the Latin and the Cyrillic alphabets.

1. Background

The history of the Interslavic or Pan-Slavic language is closely connected with Pan-Slavism, an ideology that endeavors cultural and political unification of all Slavs, based on the conception that all Slavic people are part of a single Slavic nation. Along with this belief came also the need for a Slavic umbrella language. A strong candidate for that position was Russian, the language of the largest (and during most of the 19th century the only) Slavic state and also mother tongue of more than half of the Slavs. This option enjoyed most of its popularity in Russia itself, but was also favoured by Pan-Slavists abroad, for example the Slovak Ľudovít Štúr.[1] Others believed that Old Church Slavonic was a better and also more neutral solution. In previous centuries, this language had served as an administrative language in a large part of the Slavic world, and it was still used on a large scale in Orthodox liturgy, where it played a role similar to Latin in the West. Old Church Slavonic had the additional advantage of being very similar to the common ancestor of the Slavic languages, Proto-Slavic. However, Old Church Slavonic had several practical disadvantages as well: it was written in a highly archaic form of Cyrillic, its grammar was complex, and its vocabulary was characterized by many obsolete words as well as the absence of words for modern concepts. Hence, early examples of Pan-Slavic language projects were aimed at modernizing Old Church Slavonic and adapting it to the needs of everyday communication.

1.1. Early Projects

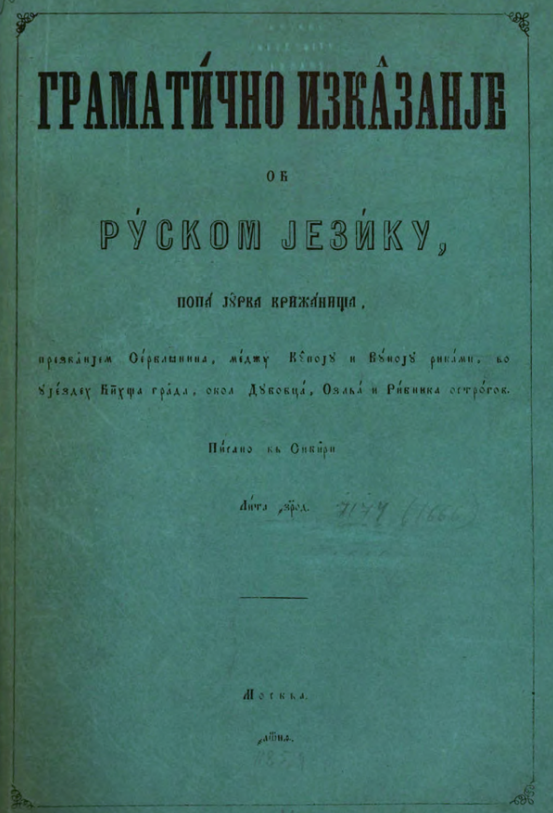

The first Interslavic grammar, Gramatíčno izkâzanje ob rúskom jezíku by the Croatian priest Juraj Križanić, was written in 1665.[2] He referred to the language as Ruski, but in reality it was mostly based on a mixture of the Russian edition of Church Slavonic and his own Ikavian Čakavian dialect of Croatian. Križanić used it not only for this grammar, but also in other works, including the treatise Politika (1663–1666). According to an analysis of the Dutch Slavist Tom Ekman, 59% of the words used in Politika are of common Slavic descent, 10% come from Russian and Church Slavonic, 9% from Croatian and 2.5% from Polish.[3]

Križanić was not the first who attempted writing in a language understandable to all Slavs. In 1583 another Croatian priest, Šime Budinić, had translated the Summa Doctrinae Christanae by Petrus Canisius into "Slovignsky",[4] in which he used both the Latin and Cyrillic alphabets.[5]

After Križanić, numerous other efforts have been made to create an umbrella language for the speakers of Slavic languages.[6] A notable example is Universalis Lingua Slavica by the Slovak attorney Ján Herkeľ (1786–1853), published in Latin and in Slovak in 1826.[7][8] Unlike Križanić' project, this project was closer to the West Slavic languages.

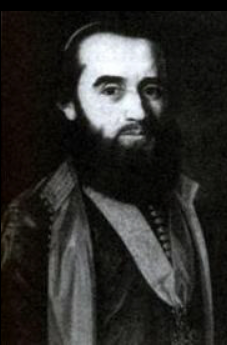

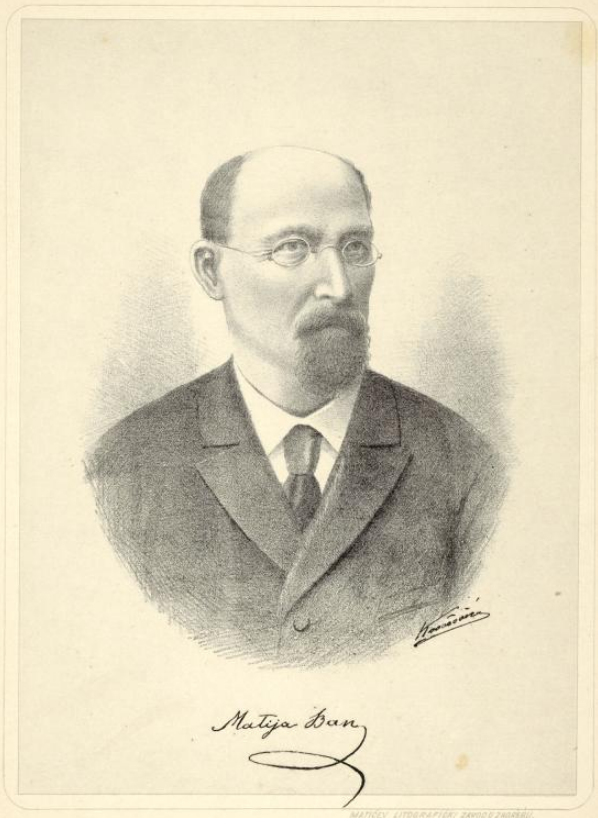

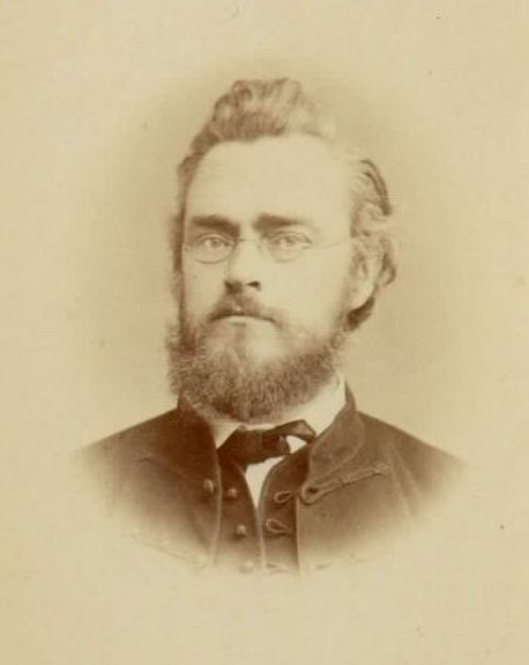

During the second half of the 19th century Pan-Slavic language projects were mostly the domain of Slovenes and Croats. In this era of awakening national consciousness, the Russians were the only Slavs who had their own state; other Slavic peoples inhabited large, mostly non-Slavic states, and clear borders between the various nations were mostly lacking. Among the numerous efforts at creating written standards for the South Slavic languages there were also efforts at establishing a common South Slavic language, Illyrian, that might also serve as a literary language for all Slavs in the future. Of special importance is the work of Matija Majar (1809–1892), a Slovenian Austroslavist who later converted to Pan-Slavism. In 1865 he published Uzajemni Pravopis Slavjanski ("Mutual Slavic Orthography").[9] In this work, he postulated that the best way for Slavs to communicate with other Slavs was by taking their own language as a starting point and then modifying it in steps. First, he proposed changing the orthography of each individual language into a generic ("mutual") Pan-Slavic orthography, subsequently he described a grammar that was based on comparing five major Slavic languages of his days: Old Church Slavonic, Russian, Polish, Czech and Serbian. Apart from a book about the language itself, Majar also used it for a biography of Cyril and Methodius[10] and for a magazine he published in the years 1873–1875, Slavjan. A fragment in the language can still be seen on the altar of Majar's church in Görtschach.[11] Other Pan-Slavic language projects were published in the same period by the Croatian Matija Ban,[12] the Slovenes Radoslav Razlag (sl) and Božidar Raič (sl),[13] as well as the Macedonian Bulgarian Grigor Parlichev[14] – all based on the idea of combining Old Church Slavonic with elements from the modern South Slavic languages.

- Authors of Pan-Slavic language projects in the 19th century

-

Stefan Stratimirović (1757–1836). https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1481459

-

Matija Ban (1818–1903). https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1397250

-

Radoslav Razlag (1826–1880). https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1826240

-

Božidar Raič (1827–1886). https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1178689

-

Matija Majar-Ziljski (1809–1892). https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1167958

-

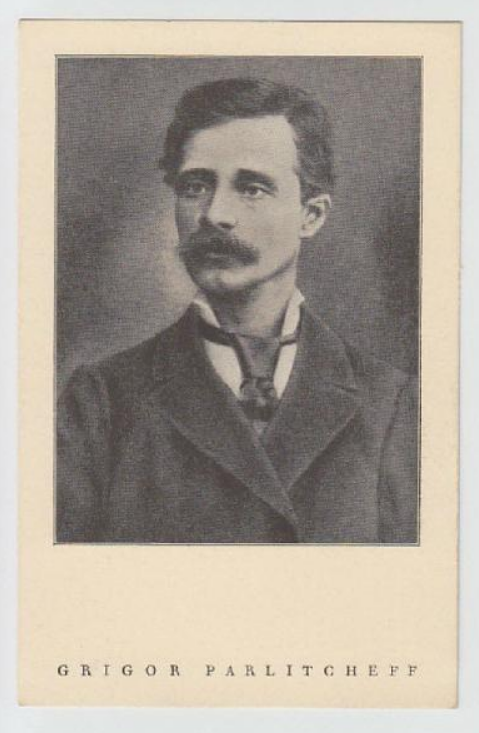

Grigor Parlichev (1830–1893). https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1341647

All authors mentioned above were motivated by the belief that all Slavic languages were dialects of one single Slavic language rather than separate languages. They deplored the fact that these dialects had diverged beyond mutual comprehensibility, and the Pan-Slavic language they envisioned was intended to reverse this process. Their long-term objective was that this language would replace the individual Slavic languages.[15]:86 Majar, for example, compared the Pan-Slavic language with standardized languages like Ancient Greek and several modern languages:

“ The ancient Greeks spoke and wrote in four dialects, but nevertheless they had one single Greek language and one single Greek literature. Many modern educated nations, for example the French, the Italians, the English and the Germans, have a higher number of more divergent dialects and subdialects than we Slavs, and yet they have one single literary language. What is possible for other nations and what really exists among them, why should this be impossible only for us Slavs?[10]:154 ” — Matija Majar, Sveta brata Ciril i Metod, slavjanska apostola i osnovatelja slovstva slavjanskoga (1864)

Consequently, these authors did not consider their projects constructed languages at all. In most cases they provided grammatical comparisons between the Slavic languages, sometimes but not always offering solutions they labelled as "Pan-Slavic". What their projects have in common that they neither have a rigidly prescriptive grammar, nor a separate vocabulary.

1.2. The Twentieth Century

In the early 20th century it had become clear that the divergence of the Slavic languages was irreversible and the concept of a Pan-Slavic literary language was no longer realistic. The Pan-Slavic dream had lost most of its power, and Pan-Slavists had to satisfy themselves with the formation of two multinational Slavic states, Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia. However, the need for a common language of communication for Slavs was still felt, and due to the influence of constructed languages like Esperanto, efforts were made to create a language that was no longer supposed to replace the individual Slavic languages, but to serve as an additional second language for Interslavic communication.[15]:118

In the same period, the nexus of Interslavic activity shifted to the North, especially to the Czech lands. In 1907 the Czech dialectologist Ignác Hošek (1852–1919) published a grammar of Neuslavisch, a proposal for a common literary language for all Slavs within the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy.[16] Five years later another Czech, Josef Konečný, published Slavina, a "Slavic Esperanto", which however had very little in common with Esperanto, but instead was mostly based on Czech.[17][18]:196 Whereas these two projects were naturalistic, the same cannot be said about two other projects by Czech authors, Slovanština by Edmund Kolkop[19] and Slavski jezik by Bohumil Holý.[20] Both projects, published in 1912 and 1920 respectively, show a clear tendency towards simplification, for example by eliminating grammatical gender and cases, and schematicism.[18]:214 [15]:128–132, 137–143, 159

During the 1950s the Czech poet and former Esperantist Ladislav Podmele (1920–2000), also known under his pseudonym Jiří Karen, worked for several years with a team of prominent interlinguists on an elaborate project, Mežduslavjanski jezik ("Interslavic language"). Among other things, they wrote a grammar, an Esperanto–Interslavic word list, a dictionary, a course and a textbook. Although none of those were ever published, the project gained some attention of linguists from various countries.[18]:301–302[21] Probably due to the political reality of those days, this language was primarily based on Russian.

1.3. The Digital Age

Although Pan-Slavism has not played a role of any significance since the collapse of the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia, globalization and new media like the Internet have led to a renewed interest in a language that would be understandable for all Slavs alike. Older projects were largely forgotten, but as it became relatively easy for authors of new projects to publish their work, several new projects emerged.[22] Most of them originated from Slavic émigrée circles.[23] During the first years of the 21st century, especially Slovio of the Slovak Mark Hučko acquired some fame. Unlike most previous projects it was not a naturalistic, but a schematic language, its grammar being based largely on Esperanto.[24] Slovio was not only intended to serve as an auxiliary language for Slavs, but also for use on a global scale like Esperanto. For that reason it gained little acceptance among Slavs: a high degree of simplification, characteristic for most international auxiliary languages, makes it easier to learn for non-Slavs, but widens the distance with the natural Slavic languages and gives the language an overly artificial character, which by many is considered a disadvantage.[25]

In March 2006, the Slovianski project was started by a group of people from different countries, who felt the need for a simple and neutral Slavic language that the Slavs could understand without prior learning. The language they envisioned should be naturalistic and only consist of material existing in all or most Slavic languages, without any artificial additions.[25][26] Initially, Slovianski was being developed in two different variants: a naturalistic version known as Slovianski-N (initiated by Jan van Steenbergen and further developed by Igor Polyakov), and a more simplified version known as Slovianski-P (initiated by Ondrej Rečnik and further developed by Gabriel Svoboda). The difference was that Slovianski-N had six grammatical cases, while Slovianski-P—like English, Bulgarian and Macedonian—used prepositions instead. Apart from these two variants (N stands for naturalism, P for pidgin or prosti "simple"), a schematic version, Slovianski-S, has been experimented with as well, but was abandoned in an early stage of the project.[27] In 2009 it was decided that only the naturalistic version would be continued under the name Slovianski. Although Slovianski had three genders (masculine, feminine, neuter), six cases and full conjugation of verbs—features usually avoided in international auxiliary languages—a high level of simplification was achieved by means of simple, unambiguous endings and irregularity being kept to a minimum.

Slovianski was mostly used in Internet traffic and in a news letter, Slovianska Gazeta.[28][29] In February and March 2010 there was much publicity about Slovianski after articles had been dedicated to it on the Polish internet portal Interia.pl[30] and the Serbian newspaper Večernje Novosti.[31] Shortly thereafter, articles about Slovianski appeared in the Slovak newspaper Pravda,[32] on the news site of the Czech broadcasting station ČT24,[33] in the Serbian blogosphere[34] and the Serbian edition of Reader's Digest,[35] as well as other newspapers and internet portals in the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Serbia, Montenegro, Bulgaria and Ukraine.[36][37][38][39][40][41][42][43][44][45][46]

Slovianski has played a role in the development of other, related projects as well. Rozumio (2008) and Slovioski (2009) were both efforts to build a bridge between Slovianski and Slovio. Originally, Slovioski, developed by Polish-American Steeven Radzikowski, was merely intended to reform Slovio, but gradually it developed into a separate language. Like Slovianski, it was a collaborative project that existed in two variants: a "full" and a simplified version.[47] In January 2010 a new language was published, Neoslavonic ("Novoslovienskij", later "Novoslověnsky") by the Czech Vojtěch Merunka, based on Old Church Slavonic grammar but using part of Slovianski's vocabulary.[48][49]

In 2011, Slovianski, Slovioski and Novoslověnsky merged into one common project under the name Interslavic (Medžuslovjanski).[27] Slovianski grammar and dictionary were expanded to include all options of Neoslavonic as well, turning it into a more flexible language based on prototypes rather than fixed rules. From that time Slovianski and Neoslavonic have no longer been developed as separate projects, even though their names are still frequently in use as synonyms or "dialects" of Interslavic.[50]

In the same year, the various simplified forms of Slovianski and Slovioski that were meant to meet the needs of beginners and non-Slavs, were reworked into a highly simplified form of Interslavic, Slovianto.[51]

After the 2017 CISLa conference, the project of unifying the two standards of Interslavic has been commenced by Merunka and van Steenbergen, with a planned new, singular grammar and orthography. An early example of this endeavor is Merunka and van Steenbergen's joint publication on Slavic cultural diplomacy, released to coincide with the conference.[52]

2. Community

Vojtěch Merunka and Jan van Steenbergen at the Second Interslavic Conference in 2018. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1383107

The number of people who speak Interslavic is difficult to establish; the lack of demographic data is a common problem among constructed languages, so that estimates are always rough. In 2012, the Bulgarian author G. Iliev mentioned a number of "several hundreds" of Slovianski speakers.[53] In 2014, the language's Facebook page mentioned 4600 speakers.[54] For comparison, 320,000 people claimed to speak Esperanto in the same year. Although these figures are notoriously unreliable, Amri Wandel considered them useful for calculating the number of Esperanto speakers worldwide, resulting in a number of 1,920,000 speakers.[55] If applied on Interslavic, this method would give a number of 27,600 speakers. A more realistic figure is given in 2017 by Kocór e.a., who estimated the number of Interslavic speakers to be 2000.[56]

Interslavic has an active online community, including four Facebook groups with 13060, 856, 316 and 117 members respectively by 25 April 2021[57][58][59][60] and an Internet forum with around 482 members.[61] Apart from that there are groups on VKontakte (1524 members),[62] Discord (1128 members)[63] and Telegram (366 members).[64] Of course, not every person who has joined a group or organization, or has registered in a language course, is automatically a speaker of the language, but on the other hand, not every speaker is automatically a member. Besides, membership figures have traditionally been used for calculations of Esperanto speakers as well, even though not every member could actually speak the language.[55] Considering the overlap between different groups, the Interslavic online community consists of at least 11,000 people, making it the constructed language with the largest online community after Esperanto.

The project has two online news portals,[65][66] a peer-reviewed expert journal focusing on issues of Slavic peoples in the wider sociocultural context of current times[67] and a wiki[68] united with a collection of texts and materials in Interslavic language somewhat similar to Wikisource.[69] Since 2016, Interslavic is used in the scientific journal Ethnoentomology for paper titles, abstracts and image captions.[70]

In June 2017 an international conference took place in the Czech town of Staré Město near Uherské Hradiště, which was dedicated to Interslavic.[71][72] The presentations were either held in Interslavic or translated into Interslavic. A second conference took place in 2018. In the same year, Vít Jedlička, president of the micronation Liberland expressed his intention to host a congress about Interslavic.[73] A third conference was planned in Hodonín in 2020, but was postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

3. Phonology

The phonemes that were chosen for Interslavic were the most popular Slavic phonemes cross-linguistically.

3.1. Consonants

| Labial | Alveolar /Dental |

Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | pal. | plain | pal. | plain | pal. | plain | pal. | ||

| Nasal | m | n | nʲ | ||||||

| Stop | p b |

t d |

tʲ dʲ |

k ɡ |

|||||

| Affricate | t͡s | t͡ʃ d͡ʒ |

t͡ɕ d͡ʑ |

||||||

| Fricative | f v |

s z |

sʲ zʲ |

ʃ ʒ |

x | ||||

| Approximant | j | ||||||||

| Trill | r | rʲ | |||||||

| Lateral | ɫ | ʎ | |||||||

4. Alphabet

One of the main principles of Interslavic is that it can be written on any Slavic keyboard.[75] Since the border between Latin and Cyrillic runs through the middle of Slavic territory, Interslavic has an official orthography for both alphabets. Because of the differences between for example the Polish alphabet and other Latin alphabets, as well as between Serbian/Macedonian Cyrillic and other forms of Cyrillic, alternative spellings are allowed as well. Because Interslavic is not an ethnic language, there are no hard and fast rules regarding accentuation either.

What all varieties of Interslavic have in common is the following basic set of phonemes that can be found in all or most Slavic languages:

| Latin | Cyrillic | Alternative representations | Pronunciation |

|---|---|---|---|

| A a | A а | ɑ ~ a | |

| B b | Б б | b | |

| C c | Ц ц | ts | |

| Č č | Ч ч | Lat. cz, cx | tʃ ~ tʂ |

| D d | Д д | d | |

| DŽ dž | ДЖ дж | Lat. dż, dzs, dzx

Cyr: џ, ӂ |

dʒ ~ dʐ |

| E e | Е е | ɛ ~ e | |

| Ě ě | Є є | usually: Lat. e, Cyr. е (or formerly ѣ) | jɛ ~ ʲɛ ~ ɛ |

| F f | Ф ф | f | |

| G g | Г г | ɡ ~ ɦ | |

| H h | Х х | x | |

| I i | И и | i ~ ji | |

| J j | Ј ј | Cyr. й | j |

| K k | К к | k | |

| L l | Л л | l ~ ɫ | |

| Lj lj | Љ љ | Cyr. ль | lʲ ~ ʎ |

| M m | М м | m | |

| N n | Н н | n | |

| Nj nj | Њ њ | Lat. ň

Cyr. нь |

nʲ ~ ɲ |

| O o | О о | ɔ | |

| P p | П п | p | |

| R r | Р р | r | |

| S s | С с | s | |

| Š š | Ш ш | Lat. sz, sx | ʃ ~ ʂ |

| T t | Т т | t | |

| U u | У у | u | |

| V v | В в | v ~ ʋ | |

| Y y | Ы ы | Lat. i, Cyr. и | i ~ ɪ ~ ɨ |

| Z z | З з | z | |

| Ž ž | Ж ж | Lat. ż, zs, zx | ʒ ~ ʐ |

Apart from the basic alphabet above, the Interslavic Latin alphabet has a set of optional letters as well. They differ from the standard orthography by carrying a diacritic and are used to convey additional etymological information and link directly to Proto-Slavic and Old Church Slavonic. The purpose of these characters is threefold:

- they allow for a more precise pronunciation,

- because sound changes from Proto-Slavic tend to be regular in all Slavic languages, they can be linked to a particular phoneme in every individual Slavic language, thus enhancing comprehensibility,

- by writing and/or pronouncing them in a different way, they can be used to manipulate the language in such way that it becomes more understandable for speakers of particular languages (in a process called "flavorization").

| Latin | Notes | Pronunciation |

|---|---|---|

| Å å | in Proto-Slavic TorT and TolT sequences | ɒ |

| Ę ę | Matches OCS ѧ | jæ ~ ʲæ |

| Ų ų | Matches OCS ѫ | u ~ o ~ ow |

| Ė ė | Matches OCS strong front jer | æ ~ ɛ ~ ǝ |

| Ȯ ȯ | Matches OCS strong back jer | ə |

| Ć ć | Proto-Slavic tj (OCS щ) | ʨ |

| Đ đ | Proto-Slavic dj (OCS дж) | ʥ |

| D́ d́ | Softened d | dʲ ~ ɟ ~ d |

| Ĺ ĺ | Softened l | ʎ ~ l |

| Ń ń | Softened n | ɲ ~ n |

| Ŕ ŕ | Softened r | rʲ ~ r̝ ~ r |

| Ś ś | Softened s | sʲ ~ ɕ ~ s |

| T́ t́ | Softened t | tʲ ~ c ~ t |

| Ź ź | Softened z | zʲ ~ ʑ ~ z |

The consonants ľ, ń, ŕ, ť, ď, ś and ź are softened or palatalized counterparts of l, n, r, t, d, s and z. The latter may also be pronounced like their softened/palatalized equivalents before i, ě, ę and possibly before e. This pronunciation is not mandatory, though: they may as well be written and pronounced hard.

Cyrillic equivalents of the etymological alphabet and ligatures can also be encountered in some Interslavic texts, though they are not part of any officially sanctioned spelling.

5. Morphology

Interslavic grammar is based on the greatest common denominator of that of the natural Slavic languages, and partly also a simplification thereof. It consists of elements that can be encountered in all or at least most of them.[76]

5.1. Nouns

Interslavic is an inflecting language. Nouns can have three genders, two numbers (singular and plural), as well as six cases (nominative, accusative, genitive, dative, instrumental and locative). Since several Slavic languages also have a vocative, it is usually displayed in tables as well, even though strictly speaking the vocative is not a case. It occurs only in the singular of masculine and feminine nouns.

There is no article. The complicated system of noun classes in Slavic has been reduced to four or five declensions:

- masculine nouns (ending in a – usually hard – consonant): dom "house", mųž "man"

- feminine nouns ending in -a: žena "woman", zemja "earth"

- feminine nouns ending in a soft consonant: kosť "bone"

- neuter nouns ending in -o or -e: slovo "word", morje "sea"

- Old Church Slavonic also had a consonantal declension that in most Slavic languages merged into the remaining declensions. Some Interslavic projects and writers preserve this declension, which consists of nouns of all three genders, mostly neuters:

- neuter nouns of the group -mę/-men-: imę/imene "name"

- neuter nouns of the group -ę/-ęt- (children and young animals): telę/telęte "calf"

- neuter nouns of the group -o/-es-: nebo/nebese "heaven"

- masculine nouns of the group -en-: kameń/kamene "stone"

- feminine nouns with the ending -òv: cŕkòv/cŕkve "church"

- feminine nouns with the ending -i/-er-: mati/matere "mother"

| masculine | neuter | feminine | consonantal | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hard, animate | hard, non-animate | soft, animate | soft, non-animate | hard | soft | -a, hard | -a, soft | -Ø | m. | n. | f. | |

| singular | ||||||||||||

| N. | brat "brother" | dom "house" | mųž "man" | kraj "land" | slovo "word" | morje "sea" | žena "woman" | zemja "earth" | kost́ "bone" | kamen "stone" | imę "name" | mati "mother" |

| A. | brata | dom | mųža | kraj | slovo | morje | ženų | zemjų | kost́ | kamen | imę | mater |

| G. | brata | doma | mųža | kraja | slova | morja | ženy | zemje | kosti | kamene | imene | matere |

| D. | bratu | domu | mųžu | kraju | slovu | morju | ženě | zemji | kosti | kameni | imeni | materi |

| I. | bratom | domom | mųžem | krajem | slovom | morjem | ženojų | zemjejų | kost́jų | kamenem | imenem | materjų |

| L. | bratu | domu | mųžu | kraju | slovu | morju | ženě | zemji | kosti | kameni | imeni | materi |

| V. | brate | dome | mųžu | kraju | slovo | morje | ženo | zemjo | kosti | kameni | imę | mati |

| plural | ||||||||||||

| N. | brati | domy | mųži | kraje | slova | morja | ženy | zemje | kosti | kameni | imena | materi |

| A. | bratov | domy | mųžev | kraje | slova | morja | ženy | zemje | kosti | kameni | imena | materi |

| G. | bratov | domov | mųžev | krajev | slov | morej | žen | zem(ej) | kostij | kamenev | imen | materij |

| D. | bratam | domam | mųžam | krajam | slovam | morjam | ženam | zemjam | kost́am | kamenam | imenam | materam |

| I. | bratami | domami | mųžami | krajami | slovami | morjami | ženami | zemjami | kost́ami | kamenami | imenami | materami |

| L. | bratah | domah | mųžah | krajah | slovah | morjah | ženah | zemjah | kost́ah | kamenah | imenah | materah |

5.2. Adjectives

Adjectives are always regular. They agree with the noun they modify in gender, case and number, and are usually placed before it. In the column with the masculine forms, the first relates to animate nouns, the second to inanimate nouns. A distinction is made between hard and soft stems, for example: dobry "good" and svěži "fresh":

| hard | soft | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m. | n. | f. | m. | n. | f. | |

| singular | ||||||

| N. | dobry | dobro | dobra | svěži | svěže | svěža |

| A. | dobrogo/dobry | dobro | dobrų | svěžego/svěži | svěže | svěžų |

| G. | dobrogo | dobrogo | dobroj | svěžego | svěžego | svěžej |

| D. | dobromu | dobromu | dobroj | svěžemu | svěžemu | svěžej |

| I. | dobrym | dobrym | dobrojų | svěžim | svěžim | svěžejų |

| L. | dobrom | dobrom | dobroj | svěžem | svěžem | svěžej |

| plural | ||||||

| N. | dobri/dobre | dobre | dobre | svěži/svěže | svěže | svěže |

| A. | dobryh/dobre | dobre | dobre | svěžih/svěže | svěža | svěže |

| G. | dobryh | svěžih | ||||

| D. | dobrym | svěžim | ||||

| I. | dobrymi | svěžimi | ||||

| L. | dobryh | svěžih | ||||

Some writers do not distinguish between hard and soft adjectives. One can write dobrego instead of dobrogo, svěžogo instead of svěžego.

Comparison

The comparative is formed with the ending -(ěj)ši: slabši "weaker", pòlnějši "fuller". The superlative is formed by adding the prefix naj- to the comparative: najslabši "weakest". Comparatives can also be formed with the adverbs bolje or vyše "more", superlatives with the adverbs najbolje or najvyše "most".

Adverbs

Hard adjectives can be turned into an adverb with the ending -o, soft adjectives with the ending -e: dobro "well", svěže "freshly". Comparatives and superlatives can be adverbialized with the ending -ěje: slaběje "weaker".

5.3. Pronouns

The personal pronouns are: ja "I", ty "you, thou", on "he", ona "she", ono "it", my "we", vy "you" (pl.), oni "they". When a personal pronoun of the third person is preceded by a preposition, n- is placed before it.

| singular | plural | reflexive | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person | 2nd person | 3rd person | 1st person | 2nd person | 3rd person | ||||

| masculine | neuter | feminine | |||||||

| N. | ja | ty | on | ono | ona | my | vy | oni | — |

| A. | mene (mę) | tebe (tę) | jego | jų | nas | vas | jih | sebe (sę) | |

| G. | mene | tebe | jego | jej | sebe | ||||

| D. | mně (mi) | tobě (ti) | jemu | jej | nam | vam | jim | sobě (si) | |

| I. | mnojų | tobojų | nim | njų | nami | vami | njimi | sobojų | |

| L. | mně | tobě | nim | njej | nas | vas | njih | sobě | |

Other pronouns are inflected as adjectives:

- the possessive pronouns moj "my", tvoj "your, thy", naš "our", vaš "your" (pl.), svoj "my/your/his/her/our/their own", as well as čij "whose"

- the demonstrative pronouns toj "this, that", tutoj "this" and tamtoj "that"

- the relative pronoun ktory "which"

- the interrogative pronouns kto "who" and čto "what"

- the indefinite pronouns někto "somebody", něčto "something", nikto "nobody", ničto "nothing", ktokoli "whoever, anybody", čto-nebųď "whatever, anything", etc.

5.4. Numerals

The cardinal numbers 1–10 are: 1 – jedin/jedna/jedno, 2 – dva/dvě, 3 – tri, 4 – četyri, 5 – pęt́, 6 – šest́, 7 – sedm, 8 – osm, 9 – devęt́, 10 – desęt́.

Higher numbers are formed by adding -nadsęť for the numbers 11–19, -desęt for the tens, -sto for the hundreds. Sometimes (but not always) the latter is inflected: dvasto/tristo/pęt́sto and dvěstě/trista/pęt́sȯt are both correct.

The inflection of the cardinal numerals is shown in the following table. The numbers 5–99 are inflected either as nouns of the kosť type or as soft adjectives.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m. | n. | f. | m./n. | f. | ||||

| N. | jedin | jedno | jedna | dva | dvě | tri | četyri | pęt́ |

| A. | jedin | jedno | jednų | dva | dvě | tri | četyri | pęt́ |

| G. | jednogo | jednoj | dvoh | trěh | četyrěh | pęti | ||

| D. | jednomu | jednoj | dvoma | trěm | četyrěm | pęti | ||

| I. | jednym | jednojų | dvoma | trěma | četyrmi | pęt́jų | ||

| L. | jednom | jednoj | dvoh | trěh | četyrěh | pęti | ||

Ordinal numbers are formed by adding the adjective ending -y to the cardinal numbers, except in the case of pŕvy "first", drugy/vtory "second", tretji "third", četvŕty "fourth", stoty/sȯtny "hundredth", tysęčny "thousandth".

Fractions are formed by adding the suffix -ina to ordinal numbers: tretjina "(one) third", četvŕtina "quarter", etc. The only exception is pol (polovina, polovica) "half".

Interslavic has other categories of numerals as well:

- collective numerals: dvoje "pair, duo, duet", troje, četvero..., etc.

- multiplicative numerals: jediny "single", dvojny "double", trojny, četverny..., etc.

- differential numerals: dvojaky "of two different kinds", trojaky, četveraky..., enz.

5.5. Verbs

Aspect

Like all Slavic languages, Interslavic verbs have grammatical aspect. A perfective verb indicates an action that has been or will be completed and therefore emphasizes the result of the action rather than its course. On the other hand, an imperfective verb focuses on the course or duration of the action, and is also used for expressing habits and repeating patterns.

Verbs without a prefix are usually imperfective. Most imperfective verbs have a perfective counterpart, which in most cases is formed by adding a prefix:

dělati ~ sdělati "to do"

čistiti ~ izčistiti "to clean"

pisati ~ napisati "to write"

Because prefixes are also used to change the meaning of a verb, secondary imperfective forms based on perfective verbs with a prefix are needed as well. These verbs are formed regularly:

- -ati becomes -yvati (e.g. zapisati ~ zapisyvati "to note, to register, to record", dokazati ~ dokazyvati "to prove")

- -iti become -jati (e.g. napraviti ~ napravjati "to lead", pozvoliti ~ pozvaljati "to allow", oprostiti ~ oprašćati "to simplify")

Some aspect pairs are irregular, for example nazvati ~ nazyvati "to name, to call", prijdti ~ prihoditi "to come", podjęti ~ podimati "to undertake".

Stems

The Slavic languages are notorious for their complicated conjugation patterns. To simplify these, Interslavic has a system of two conjugations and two verbal stems. In most cases, knowing the infinitive is enough to establish both stems:

- the first stem is used for the infinitive, the past tense, the conditional mood, the past passive participle and the verbal noun. It is formed by removing the ending -ti from the infinitive: dělati "to do" > děla-, prositi "to require" > prosi-, nesti "to carry" > nes-. Verbs ending in -sti can also have their stem ending on t or d, f.ex. vesti > ved- "to lead", gnesti > gnet- "to crush".

- the second stem is used for the present tense, the imperative and the present active participle. In most cases both stems are identical, and in most of the remaining cases the second stem can be derived regularly from the first. In particular cases they have to be learned separately. In the present tense, a distinction is made between two conjugations:

- the first conjugation includes almost all verbs that do not have the ending -iti, as well as monosyllabic verbs on -iti:

- verbs on -ati have the stem -aj-: dělati "to do" > dělaj-

- verbs on -ovati have the stem -uj-: kovati "to forge" > kuj-

- verbs on -nųti have the stem -n-: tęgnųti "to pull, to draw" > tęgn-

- monosyllabic verbs have -j-: piti "to drink" > pij-, čuti "to feel" > čuj-

- the second stem is identical to the first stem if the latter ends in a consonant: nesti "to carry" > nes-, vesti "to lead" > ved-

- the second conjugation includes all polysyllabic verbs on -iti and most verbs on -ěti: prositi "to require" > pros-i-, viděti "to see" > vid-i-

- the first conjugation includes almost all verbs that do not have the ending -iti, as well as monosyllabic verbs on -iti:

There are also mixed and irregular verbs, i.e. verbs with a second stem that cannot be derived regularly from the first stem, for example: pisati "to write" > piš-, spati "to sleep" > sp-i-, zvati "to call" > zov-, htěti "to want" > hoć-. In these cases both stem have to be learned separately.

Conjugation

The various moods and tenses are formed by means of the following endings:

- Present tense: -ų, -eš, -e, -emo, -ete, -ųt (first conjugation); -jų, -iš, -i, -imo, -ite, -ęt (second conjugation)

- Past tense – simple (as in Russian): m. -l, f. -la, n. -lo, pl. -li

- Past tense – complex (as in South Slavic):

- Imperfect tense: -h, -še, -še, -hmo, -ste, -hų

- Perfect tense: m. -l, f. -la, n. -lo, pl. -li + the present tense of byti "to be"

- Pluperfect tense: m. -l, f. -la, n. -lo, pl. -li + the imperfect tense of byti

- Conditional: m. -l, f. -la, n. -lo, pl. -li + the conditional of byti

- Future tense: the future tense of byti + the infinitive

- Imperative: -Ø, -mo, -te after j, or -i, -imo, -ite after another consonant.

The forms with -l- in the past tense and the conditional are actually participles known as the L-participle. The remaining participles are formed as follows:

- Present active participle: -ųći (first conjugation), -ęći (second conjugation)

- Present passive participle: -omy/-emy (first conjugation), -imy (second conjugation)

- Past active participle: -vši after a vowel, or -ši after a consonant

- Past passive participle: -ny after a vowel, -eny after a consonant. Monosyllabic verbs (except for those on -ati) have -ty. Verbs on -iti have the ending -jeny.

The verbal noun is based on the past passive participle, replacing the ending -ny/-ty with -ńje/-t́je.

Examples

|

|

|

|

Whenever the stem of a verbs of the second conjugation ends in s, z, t, d, st or zd, an ending starting -j causes the following mutations:

- prositi "to require": pros-jų > prošų, pros-jeny > prošeny

- voziti "to transport": voz-jų > vožų, voz-jeny > voženy

- tratiti "to lose": trat-jų > traćų, trat-jeny > traćeny

- slěditi "to follow": slěd-jų > slědžų, slěd-jeny > slědženy

- čistiti "to clean": čist-jų > čišćų, čist-jeny > čišćeny

- jezditi "to go (by transport)": jezd-jų > ježdžų, jezd-jeny > ježdženy

Alternative forms

Because Interslavic is not a highly formalized language, a lot of variation occurs between various forms. Often used are the following alternative forms:

- In the first conjugation, -aje- is often reduced to -a-: ty dělaš, on děla etc.

- Instead of the 1st person singular ending -(j)ų, the ending -(e)m is sometimes used as well: ja dělam, ja hvalim, ja nesem.

- Instead of -mo in the 1st person plural, -me can be used as well: my děla(je)me, my hvalime.

- Instead of -hmo in the imperfect tense, -smo and the more archaic -hom can be used as well.

- Instead of the conjugated forms of byti in the conditional (byh, bys etc.), by is often used as a particle: ja by pisal(a), ty by pisal(a) etc.

- Verbal nouns can have the ending -ije instead of -je: dělanije, hvaljenije.

Irregular verbs

A few verbs have an irregular conjugation:

- byti "to be" has jesm, jesi, jest, jesmo, jeste, sųt in the present tense, běh, běše... in the imperfect tense, and bųdų, bųdeš... in the future

- dati "to give", jěsti "to eat" and věděti "to know" have the following present tense: dam, daš, da, damo, date, dadųt; jem, ješ...; věm, věš...

- idti "to go by foot, to walk" has an irregular L-participle: šel, šla, šlo, šli.

6. Vocabulary

Words in Interslavic are based on comparison of the vocabulary of the modern Slavic languages. For this purpose, the latter are subdivided into six groups:

- Russian

- Ukrainian and Belarusian

- Polish

- Czech and Slovak

- Slovene, Croat, Serbian, Montenegrin and Bosnian

- Bulgarian and Macedonian

These groups are treated equally. In some situations even smaller languages, like Cashubian, Rusyn and Sorbian languages are included.[77] Interslavic vocabulary has been compiled in such way that words are understandable to a maximum number of Slavic speakers. The form in which a chosen word is adopted depends not only on its frequency in the modern Slavic languages, but also on the inner logic of Interslavic, as well as its form in Proto-Slavic: to ensure coherence, a system of regular derivation is applied.[78]

| English | Interslavic | Russian | Ukrainian | Belarusian | Polish | Czech | Slovak | Upper Sorbian | Slovene | Serbo-Croatian | Macedonian | Bulgarian |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| human being | člověk / чловєк | человек | чоловік (only "male human"; "human being" is "людина") | чалавек | człowiek | člověk | človek | čłowjek | človek | čovjek, čovek | човек | човек |

| dog | pes / пес | пёс, собака | пес, собака | сабака | pies | pes | pes | pos, psyk | pes | pas | пес, куче | пес, куче |

| house | dom / дом | дом | дім, будинок | дом | dom | dům | dom | dom | dom, hiša | dom, kuća | дом, куќа | дом, къща |

| book | kniga / книга | книга | книга | кніга | książka, księga | kniha | kniha | kniha | knjiga | knjiga | книга | книга |

| night | noč / ноч | ночь | ніч | ноч | noc | noc | noc | nóc | noč | noć | ноќ | нощ |

| letter | pismo / писмо | письмо | лист | пісьмо, ліст | list, pismo | dopis | list | list | pismo | pismo | писмо | писмо |

| big, large | veliky / великы | большой, великий | великий | вялікі | wielki | velký | veľký | wulki | velik | velik, golem | голем | голям |

| new | novy / новы | новый | новий | новы | nowy | nový | nový | nowy | nov | nov | нов | нов |

7. Example

The Pater Noster:

| Interslavic (Extended Latin) | Interslavic (Cyrillic) | Old Church Slavonic (Romanized) |

|---|---|---|

|

Otče naš, ktory jesi v nebesah, |

Отче наш, кторы јеси в небесах, |

Otĭče našĭ, iže jesi na nebesĭchŭ, |

8. In Popular Culture

Interslavic is featured in Václav Marhoul's movie The Painted Bird (based on novel of the same title written by Polish-American writer Jerzy Kosiński), in which it plays the role of an unspecified Slavic language, making it the first movie to have it.[81][82] Marhoul stated that he decided to use Interslavic (after searching on Google for "Slavic Esperanto") so that no Slavic nation would nationally identify with the villagers depicted as bad people in the movie.[83][84]

References

- Л.П. Рупосова, История межславянского языка, in: Вестник Московского государственного областного университета (Московский государственный областной университет, 2012 no. 1, p. 55. (in Russian)

- Juraj Križanić, Граматично изказанје об руском језику. Moscow, 1665.

- "ИЗ ИСТОРИИ ИНТЕРЛИНГВИСТИЧЕСКОЙ МЫСЛИ В РОССИИ". Miresperanto.com. http://miresperanto.com/esperantologio/interlingv_mysl.htm.

- Petrus Canisius, "Svmma navka christianskoga / sloxena castnim včitegliem Petrom Kanisiem; tvmacena iz latinskoga jazika v slovignsky, i vtisstena po zapoviedi presuetoga Otca Pape Gregoria Trinaestoga [...] Koie iz Vlasskoga, illi Latinskoga iazika, v Slouignsky Jazik protumačio iest pop Ssimvn Bvdineo Zadranin". Rome, 1583.

- Hanna Orzechowska, Mieczysław Basaj, Instytut Słowianoznawstwa (Polska Akademia Nauk), Prekursorzy słowiańskiego jezykoznawstwa porównawczego, do końca XVIII wiek. Warsaw, 1987, p. 124. (in Polish)

- Jan van Steenbergen. "Constructed Slavic Languages". Steen.free.fr. http://steen.free.fr/interslavic/constructed_slavic_languages.html.

- Ján Herkeľ, Elementa universalis linguae Slavicae e vivis dialectis eruta at sanis logicae principiis suffulta. Budapest, 1826. (in Latin)

- Ján Herkeľ, Zaklady vseslovanskeho jazyka. Vienna, 1826. (in Slovak)

- Matija Majar-Ziljski, Uzajemni Pravopis Slavjanski, to je: Uzajemna Slovnica ali Mluvnica Slavjanska. Prague, 1865.

- Matija Majar Ziljski, Sveta brata Ciril i Metod, slavjanska apostola i osnovatelja slovstva slavjanskoga. Prague, 1864.

- Robert Gary Minnich, "Collective identity formation and linguistic identities in the Austro-Italian Slovene border region", in: Dieter Stern & Christian Voss, Marginal Linguistic Identities: Studies in Slavic Contact and Borderland Varieties, p. 104.

- Matija Ban, "Osnova Sveslavjanskoga jezika", in: Dubrovnik. Cviet narodnog književstva. Svezak drugi. Zagreb, 1851, pp. 131–174. (in Croatian)

- Božidar Raič, "Vvod v slovnicų vseslavenskųjų", in: Radoslav Razlag red., Zora Jugoslavenska no. 2, Zagreb, 1853, pp. 23–44.

- Г.П. [Григор Прличев], Кратка славянска грамматика. Constantinople, 1868.

- Anna-Maria Meyer (2014) (in de). Wiederbelebung einer Utopie. Probleme und Perspektiven slavischer Plansprachen im Zeitalter des Internets (Bamberger Beiträge zur Linguistik 6). Bamberg: Univ. of Bamberg Press. ISBN 978-3-86309-233-7.

- Ignác Hošek, Grammatik der Neuslawischen Sprache. Kremsier, 1907. (in German)

- Josef Konečný, Mluvnička slovanského esperanta »Slavina«. Jednotná spisovná dorozumívací slovanská rěč pro obchod a průmysl. Sestavil Konečný J. Prague, 1912. (in Czech)

- А. Д Дуличенко, Международные вспомогательные языки. Tallinn, 1990. (in Russian)

- Edmund Kolkop, Pokus o dorozumívací jazyk slovanský. Prague, 1912. (in Czech)

- B. Holý, Slavski jezik. Stručná mluvnice dorozumívacího i jednotícího jazyka všeslovanského. S pomocí spolupracovníků podává stenograf В. Holý. Nové Město nad Metují, 1920. (in Czech)

- Věra Barandovská-Frank, "Panslawische Variationen", in: Cyril Brosch & Sabine Fiedler (eds.), Florilegium Interlinguisticum. Festschrift für Detlev Blanke zum 70. Geburtstag. Frankfurt am Main, 2011, pp. 220–223. (in German)

- Tilman Berger, "Vom Erfinden Slavischer Sprachen", in: M. Okuka & U. Schweier, eds., Germano-Slavistische Beiträge. Festschrift für P. Rehder zum 65. Geburtstag. München, 2004, ISBN:3-87690-874-4), p. 25. (in German) http://homepages.uni-tuebingen.de/tilman.berger/Publikationen/BergerPlansprachen.pdf

- Tilman Berger (2009). "Panslavismus und Internet" (in de). p. 37. http://homepages.uni-tuebingen.de/tilman.berger/Handouts/PanslavismusInternet.pdf.

- Katherine Barber, "Old Church Slavonic and the 'Slavic Identity'". University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. https://web.archive.org/web/20100607222108/http://www.unc.edu/depts/slavdept/lajanda/slav075barber.ppt

- "Error: no |title= specified when using {{Cite web}}" (in uk). Narodna.pravda.com.ua. http://narodna.pravda.com.ua/discussions/4a8f1e1b731fc/.

- Bojana Barlovac, Creation of 'One Language for All Slavs' Underway. BalkanInsight, 18 February 2010. http://www.balkaninsight.com/en/main/news/25946

- "A Short History of Interslavic". May 12, 2013. http://steen.free.fr/interslavic/history.html.

- Н. М. Малюга, "Мовознавство в питаннях і відповідях для вчителя й учнів 5 класу", in: Філологічні студії. Науковий вісник Криворізького державного педагогічного університету. Збірник наукових праць, випуск 1. Kryvyj Rih, 2008, ISBN:978-966-17-7000-2, p. 147. (in Ukrainian) http://www.nbuv.gov.ua/portal/Soc_Gum/PhSt/texts/2008-1.pdf

- Алина Петропавловская, Славянское эсперанто . Европейский русский альянс, 23 June 2007. (in Russian) http://eursa.eu/node/1337

- Ziemowit Szczerek, Języki, które mają zrozumieć wszyscy Słowianie . Interia.pl, 13 February 2010. (in Polish) http://www.ahistoria.pl/index.php/2010/02/jezyk-ktory-maja-zrozumiec-wszyscy-slowianie/

- Marko Prelević, Словијански да свако разуме. Večernje Novosti, 18 February 2010. (in Serbian) http://www.novosti.rs/code/navigate.php?Id=10&status=jedna&vest=171149

- "Slovania si porozumejú. Holanďan pracuje na jazyku slovianski". Pravda.sk. http://spravy.pravda.sk/slovania-si-porozumeju-holandan-pracuje-na-jazyku-slovianski-p6v-/sk_svet.asp?c=A100219_175827_sk_svet_p23.

- Česká televize. ""Slovianski jazik" pochopí každý". ČT24. http://www.ct24.cz/svet/81604-slovianski-jazik-pochopi-kazdy/.

- "Jedan jezik za sve Slovene". http://www.worldwide.rs/vesti/54-jedan-jezik-za-sve-slovene. . Worldwide Translations, 1 November 2014. (in Serbian)

- Gordana Knežević, Slovianski bez muke. Reader's Digest Srbija, June 2010, pp. 13–15.

- "V Nizozemsku vzniká společný jazyk pro Slovany". Denik.cz. http://www.denik.cz/ze_sveta/v-nizozemsku-vznika-spolecny-jazyk-pro-slovany-.html/.

- Jan Dosoudil, wsb.cz. "Pět let práce na společném jazyku". Týdeník ŠKOLSTVÍ. http://www.tydenik-skolstvi.cz/archiv-cisel/2010/09/pet-let-prace-na-spolecnem-jazyku/.

- Klára Ward, „Kvik Kvik“ alebo Zvieracia farma po slovensky . Z Druhej Strany, 25 February 2010. (in Slovak) http://www.zdruhejstrany.sk/%E2%80%9Ekvik-kvik%E2%80%9C-alebo-zvieracia-farma-po-slovensky/

- Péter Aranyi & Klára Tomanová, Egységes szláv nyelv születőben . Melano.hu, 23 February 2010. (in Hungarian) http://www.melano.hu/news.php?extend.185

- "Холанђанин прави пансловенски језик". Serbian Cafe. http://www3.serbiancafe.com/cir/vesti/4/71004/holandjanin-pravi-panslovenski-jezik.html.

- "PCNEN - Prve crnogorske elektronske novine". Pcnen.com. http://www.pcnen.com/detail.php?module=2&news_id=43867.

- "Датчaнин създава общ славянски език". Plovdivmedia.com. http://www.plovdivmedia.com/22230.html.

- "Начало - vsekiden.com". Vsekiden.com. http://www.vsekiden.com/?p=65542.

- "Готвят славянско есперанто". Marica.bg. http://www.marica.bg/show.php?id=21583.

- "Язык для всех славян на основе русинского". УЖГОРОД - ОКНО В ЕВРОПУ - UA-REPORTER.COM. http://www.ua-reporter.com/content/82075.

- "Linguistique : Slaves de tous les pays, parlez donc le Slovianski ! - Le Courrier des Balkans". Balkans.courriers.info. http://balkans.courriers.info/article14732.html.

- Дора Солакова, "Съвременни опити за създаване на изкуствен общославянски език", in: Езиков свят – Orbis Linguarum, Issue no.2/2010 (Югозападен Университет "Неофит Рилски", Blagoevgrad, 2010, ISSN 1312-0484), p. 248. (in Bulgarian)

- Vojtěch Merunka, Jazyk novoslovienskij. Prague 2010, ISBN:978-80-87313-51-0), pp. 15–16, 19–20. (in Czech)

- Dušan Spáčil, "Je tu nový slovanský Jazyk", in: Květy no. 31, July 2010. (in Czech) http://44adb5c4-a-62cb3a1a-s-sites.googlegroups.com/site/novoslovienskij/medializacia/Kvety-31-2010.pdf?attachauth=ANoY7criAnj7lliOyw5eboL9Y1uFIdaDr1UoPE6iaR1VRY30CUYULnCB_m7EAaXreNHceAXOrpIlBhWBpjX8psTXa65XlaMeZyL875_2n5mM8VF5Fns7QfGkIkZKCusBSNWtBTTu_KI3RyxXm40fUrT0KWHbtV6ZhV4nac-0VCGZoOzjGFF7DNe9GLixRP1y36lxsBrDJptlGP_Hx_9s9R0YHqVNKx1DdWkT-8DneWtyPFCy_L9PS3s%3D&attredirects=1

- Molhanec, Martin; Merunka, Vojtech (2016). "Neoslavonic Language Zonal Language Constructing: Challenge, Experience, Opportunity to the 21st Century". Proceedings of the 2015 2nd International Conference on Education, Language, Art and Intercultural Communication. doi:10.2991/icelaic-15.2016.60. ISBN 978-94-6252-152-0. https://dx.doi.org/10.2991%2Ficelaic-15.2016.60

- Jan van Steenbergen. "Slovianto - a Slavic Esperanto". Steen.free.fr. http://steen.free.fr/interslavic/slovianto.html.

- Vojtěch Merunka & Jan van Steenbergen (2017). "Slovjanska kulturna diplomacija - SWOT analiza, strategija i taktika do budučnosti". https://www.researchgate.net/publication/318452938.

- G. Iliev, Short History of the Cyrillic Alphabet (Plovdiv, 2012), p. 67. HTML version http://www.ijors.net/issue2_2_2013/articles/iliev.html

- "Slovianski". Facebook. http://www.facebook.com/pages/Slovianski/107932102568734?ref=ts&fref=ts.

- Amri Wandel, "How many people speak Esperanto? Or: Esperanto on the web", in: Interdisciplinary Description of Complex Systems 13(2) (2015), pp. 318-321.

- Kocór, p. 21.

- "Interslavic - Medžuslovjanski - Меджусловјански". Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/groups/interslavic/.

- "Novoslovienskij jezyk - новословіенскиј језык - neoslavonic language". Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/groups/neoslavonic/.

- "Medžuslovjansko Věće Interslavic Assembly Меджусловјанско Вече". Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/groups/1933305396885265/.

- "Nauka medžuslovjanskogo". Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/groups/learninginterslavic.

- "Slovianski forum on Tapatalk". S8.zetaboards.com. https://www.tapatalk.com/groups/slovianski/. "Sejčas pogledajete naše forum kako gosť. To znači, že imajete ograničeny dostup do někojih česti forum i ne možete koristati vse funkcije. Ako li pristupite v našu grupu, budete imati svobodny dostup do sekcij preznačenyh jedino za členov, na pr. založeňje profila, izsylaňje privatnyh poslaň i učestničstvo v glasovaňjah. Zapisaňje se jest prosto, bystro i vpolno bezplatno."

- "Межславянский - Меджусловјанскы - Interslavic on VKontakte". https://vk.com/club114071440.

- "Medžuslovjanska besěda on Discord". https://discord.com/invite/gNneu2U.

- "Меджусловянска бесѣда / Medžuslovjanska besěda on Telegram". https://t.me/interslavic.

- "GLAVNA STRANICA". Izvesti.info. http://www.izvesti.info.

- "Medžuslovjanske věsti". Twitter, Facebook. https://twitter.com/MSVesti.

- "SLOVJANI.info". Slovanská unie z.s.. http://slovjani.info/.

- "isvwiki". Isv.miraheze.org. http://isv.miraheze.org/.

- "isvwiki". Isv.miraheze.org. https://isv.miraheze.org/wiki/Sbornik:Glavna_stranica.

- Erik Tihelka, Interslavic: a new option for scientific publishing? European Science Editing 44(3), August 2018, p. 62. http://europeanscienceediting.eu/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/ESEAug18_viewpoint.pdf

- "CISLa 2017". http://cisla.slavic-union.org/.

- Jiří Králík (6 June 2017). "Dny slovanské kultury 2017 skončily". Místní kultura. http://www.mistnikultura.cz/dny-slovanske-kultury-2017-skoncily.

- Davison, Tamara (2018-06-05). "Meet The Man Who Made His Own Country: The President of Liberland Talks Blockchain, Immigration and How To Start Your Own State." (in en). https://150sec.com/free-republic-liberland/9128/.

- "Interslavic – Phonology". http://steen.free.fr/interslavic/phonology.html.

- "Orthography". Steen.free.fr. http://steen.free.fr/slovianski/phono_ortho.html#orthography.

- "Založeňja za medžuslovjanski jezyk". Izviestija.info. http://izviestija.info/index.php/nauka/195-zalozenja-za-medzuslovjanski-jezyk.

- "Voting Machine". http://steen.free.fr/interslavic/voting_machine.html.

- "Vocabulary". Steen.free.fr. http://steen.free.fr/interslavic/design_criteria.html#vocabulary.

- Jan van Steenbergen. "Otče naš – Отче наш". Steen.free.fr. http://steen.free.fr/interslavic/otcze_nasz.html.

- "Slavonic". Christusrex.org. http://www.christusrex.org/www1/pater/JPN-slavonic.html.

- "Vojtěch Merunka – Developer of the Interslavic Language Spoken in the Painted Bird". https://www.radio.cz/en/section/one-on-one/vojtech-merunka-developer-of-interslavic-language-spoken-in-the-painted-bird.

- "Error: no |title= specified when using {{Cite web}}" (in ru). https://www.radio.cz/ru/rubrika/bogema/-raskrashennaya-ptica-kinodebyut-mezhslavyanskogo-yazyka.

- kinobox.cz, team at. "Nabarvené ptáče aneb Bolestivé pochybnosti o poslání živočišného druhu Homo sapiens" (in cs). https://www.kinobox.cz/clanek/17031-vaclav-marhoul-o-nabarvenem-ptaceti.

- "Interslavic: How A Made-Up Slavic Language Made It To The Big Screen" (in en). https://www.youtube.com/watch?t=46&v=WlopfGDweTE.