Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nelson Rocha | -- | 3727 | 2022-11-03 12:04:57 | | | |

| 2 | Dean Liu | Meta information modification | 3727 | 2022-11-04 01:40:57 | | | | |

| 3 | Dean Liu | Meta information modification | 3727 | 2022-11-07 01:34:29 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Bastos, D.; Fernández-Caballero, A.; Pereira, A.; Rocha, N.P. Citizen Participation in City Management and Governance. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/32755 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Bastos D, Fernández-Caballero A, Pereira A, Rocha NP. Citizen Participation in City Management and Governance. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/32755. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Bastos, David, Antonio Fernández-Caballero, António Pereira, Nelson Pacheco Rocha. "Citizen Participation in City Management and Governance" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/32755 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Bastos, D., Fernández-Caballero, A., Pereira, A., & Rocha, N.P. (2022, November 03). Citizen Participation in City Management and Governance. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/32755

Bastos, David, et al. "Citizen Participation in City Management and Governance." Encyclopedia. Web. 03 November, 2022.

Copy Citation

Citizen participation in the management and governance of their cities is not a simple process, even when city authorities value citizen opinions. To optimize this process and face diminishing public trust due to scandals, corruption, worsening of the economic situation and inequalities, city authorities are changing and updating government mechanisms to increase citizen participation.

smart cities

citizen participation

crowdsourcing

1. Introduction

Citizens represent the lifeblood of a city and are inextricably linked to its continued existence and prosperity. Therefore, it is imperative for the government of a city to care for its citizens and to pay careful attention to their needs [1]. Moreover, citizens must be active in their cities’ management and governance, since they are aware of the problems of the communities where they live and work and can evaluate the actions of city authorities [2][3].

However, despite its importance, citizen participation in the management and governance of their cities is not a simple process, even when city authorities value citizen opinions [4]. To optimize this process and face diminishing public trust due to scandals, corruption, worsening of the economic situation and inequalities [5][6], city authorities are changing and updating government mechanisms to increase citizen participation [7][8][9]. This has naturally led to the formulation of concepts such as e-government and e-governance, where information technologies are used to deliver services and facilitate communication between different entities [10][11][12]. These concepts are also considered in smart city implementations since smart governance is a relevant smart-city domain [13][14] aiming to develop and disseminate new forms to engage citizens in city management and governance.

Smart cities presuppose intensive data collection and analysis to improve the available services [15]. However, a precise definition of what makes a smart city is a much more difficult proposition, where many definitions have been proposed, but none has achieved universal consensus [16]. Even so, it is possible to identify common elements in these diverse definitions: economic development, sustainability, environmental responsibility, citizen quality of life and focus on citizens and their needs [17][18][19][20][21].

Citizens can report pertinent data about their environments [22][23][24][25][26] and might use or allow the usage of the sensors of their mobile devices to collect heterogenous types of data [27][28][29]. Moreover, authorities might analyze public data generated by citizens during their daily lives (e.g., social networks, comment boards, or online forums) to gather ideas and opinions [30][31][32][33].

Additionally, citizens should be integrated into the decision-making processes as active participants instead of just being passive participants in providing different types of data [34][35][36][37][38][39][40][41]. This might not only increase the trust of citizens in their respective city authorities by promoting transparency and minimizing corruption [42][43] but also promote the implementation of new forms of democratic governance, such as e-democracy, which can be defined as “the practice of democracy with the support of digital media in political communication and participation” [44] and demands the communication and sharing of ideas between citizens, relevant stakeholders and authorities [45][46][47][48].

2. Citizen Participation in the Identification of Urban Problems

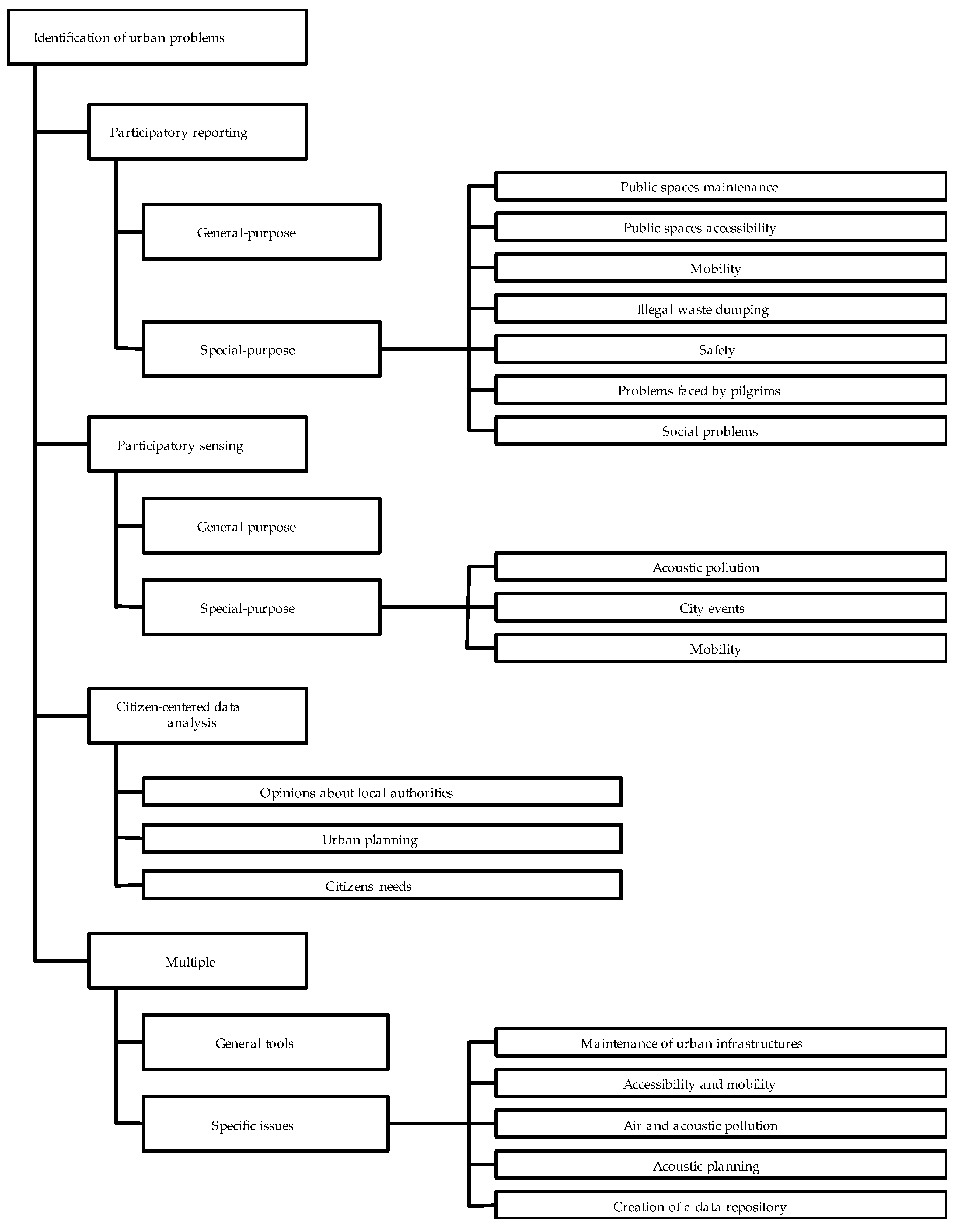

The category citizen participation in the identification of urban problems was further divided into the following subcategories (Figure 1): (1) participatory reporting (i.e., use of technologies such as crowdsourcing to allow citizens to report on urban problems), 25 studies; (2) participatory sensing (i.e., crowdsensing applications supported on the use of sensors from citizens’ personal devices to acquire diverse parameters), seven studies; (3) citizen-centered data analysis (e.g., social media data mining aiming to identify urban problems), 14 studies; and (4) multiple approaches (i.e., integration of various approaches such as participatory reporting in conjunction with citizen-centered data analysis), 13 studies.

Figure 1. The different aims and approaches of the studies classified as citizen participation in the identification of urban problems.

Participatory Reporting

Participatory reporting aims to provide city authorities with a better understanding of problems faced by the citizens. Ten studies [49][50][51][52][53][54][55][56][57][58] related to participatory reporting did not focus on specific issues, but instead described general purpose participatory reporting applications. These applications allow citizens to report on various types of issues (e.g., roads conditions, waste, traffic conditions, accidents, or crime, among others) and have various specific features: ref. [52] presented MinaQn, a web-based system that allows city officials to create questionnaires about different topics citizens can then answer; the application provided by [54] requires authentication so that the citizens can receive feedback about the status of the issues they reported; in the application described by [50], citizens must be authenticated so that their reports can be checked for quality and timeliness; the study reported by [55] was focused on the engagement of the citizens by using gamification concepts (e.g., user levels, avatars or leaderboards); ref. [51] presented an analysis engine to aggregate and consolidate the collected data; and the studies reported by [53][56][58] integrated comprehensive mechanisms to allow citizens to access services provided by the authorities (e.g., administration, education, healthcare, paying taxes or filling applications) and receive updates about city issues and the status of the reports they made.

Fifteen studies ref. [59][60][61][62][63][64][65][66][67][68][69][70][71][72][73] developed participatory reporting applications focused on specific issues: maintenance and accessibility of public spaces, mobility in the urban space, illegal waste dumping, safety, problems faced by pilgrims, and social problems (Figure 1).

The maintenance of public spaces was addressed by seven studies [59][61][65][66][68][70][73]. The applications developed by these studies allow citizens to report problems they find for proactive management of public spaces [73]. Although the participatory reporting mechanisms are similar among these studies, it is possible to distinguish specific features: ref. [59] proposed an application to allow citizens to share photos of points of interest; ref. [70] presented an application developed for the city of Tangerang, Indonesia, to allow the citizens to make suggestions from ten different categories of city development; in addition to participatory reporting, the prototype described by [65] also serves as a digital library so that citizens can have better information about their surroundings; the application presented by [61] allows the citizen to check the status of any reported issue; the application described by [66] makes use of gamification to incentivize citizens to participate; and the application reported by [68], FixMyStreet, according to official data, has been accepted by 98% of the British Councils.

In terms of the accessibility of public spaces, refs. [63][69] presented applications that allow citizens to comment and review city locations according to their accessibility to people with mobility impairments.

The study reported by [64] was focused on mobility in the urban space and presented a serious game aiming to introduce people to the concept of electric mobility and convince them of its utility. The gaming approach was chosen in lieu of more traditional surveys to investigate how gamification can improve the receptiveness of the public.

Considering that illegal waste dumping can cause social and health problems, the application proposed by [71] aimed at the quick identification of illegal waste dumping based on citizen reports. The application uses the Ethereum blockchain to create a currency that can be gained by performing certain actions on the system (e.g., reporting or voting), which can then be exchanged for goods and services from sponsors.

Since quick and efficient reporting of incidents that threaten the safety of citizens is of paramount importance, ref. [60] presented a method to increase the quality of data collected from an interactive voice response system for the city of East London, South Africa, that allows citizens to call and report safety incidents. Moreover, ref. [72] presented an application that allows two types of reports, an emergency one, where citizens only need to press a button to send pre-defined messages with their locations, or if the citizens are not in danger, four categories’ reports (i.e., criminal activity, perceived danger, suspicious activities and other) can be written and sent.

Based on the various problems pilgrims can encounter during the Hajj (Muslim holy pilgrimage), ref. [62] presented an application to share data with the city’s government and services, both from sensors and from citizen inputs, which might be used in conjunction with existing city services to support the management of the pilgrims as well as city residents.

Finally, one study [67] aimed at identifying the problems that affect minorities. In this regard, a basic foundational and theoretical framework for crowd mapping was developed to be used to create a crowd-based smart map for disabled people.

Participatory Sensing

Looking specifically at the second subcategory related to citizen participation in the identification of urban problems (i.e., participatory sensing [74][75][76][77][78][79][80]), a subset of studies [75][76][79][80] had specific aims, while another subset of studies [74][77][78] was focused on general-purpose applications to allow the creation of participatory sensing campaigns to obtain different types of data (Figure 1).

Three aims were identified in terms of special-purpose applications: acoustic pollution, city events, and urban mobility. Concerning acoustic pollution, ref. [80] presented a participatory sensing architecture that allows smart devices to become noise sensors for urban environments, while [75] described an application that might be used to provide several services to support city events (e.g., festivals or concerts) since it collects precise location information that can be used by city officials for better management during normal operations or during emergencies. Finally, two studies focused on understanding how citizens move around the cities for a better planning of the available transportation: ref. [76] presented a reference architecture for an application that collects data from mobile sources, analyzes the collected data and then gives feedback to the citizens, namely alerts of dangerous spots. The study reported by [79] used the ParticipAct platform (also used by the study reported by [63]) to store location data collected from the citizen mobile devices, which were then analyzed to infer the citizen mobility patterns (i.e., what paths they take from location to location) and identify points of interest in the cities.

Citizen-Centered Data Analysis

Fourteen studies [81][82][83][84][85][86][87][88][89][90][91][92][93][94] proposed applications that analyze citizen-centered data from social media (e.g., Facebook or Twitter) to identify needs or problems faced by the citizens to support urban planning and to determine the citizens’ opinions about the performance of local authorities (Figure 1).

Seven studies [81][83][84][86][88][89][91] were related to the identification of needs and problems faced by the citizens. The study reported by [91] used NeedFull, a tweet analysis framework, to investigate the reactions of the people of New York State during the COVID-19 pandemic, while the remaining six studies [81][83][84][86][88][89] aimed to analyze large volumes of data to understand the sentiments of the citizens about certain topics [81][83][86][88][89] or to infer alerts, insights, or recommendations [81].

Concerning urban planning, one study [85] used freely available data on citizen activities to identify common points of interest and urban areas where sports are played. In contrast, another study [94] used a machine-learning algorithm to identify citizen trends in terms of urban planning by analyzing data from a civic participation application.

Moreover, five studies [82][87][90][92][93] aimed to identify the opinion of the citizens about the local authorities. Article [92] presented an analytical framework to retrieve citizen-centered data from an online comment board to be used by local governments to assess political reforms and implementations. In turn, refs. [90][93] presented how social media can be used to generate data that municipalities can use to implement smart cities. Furthermore, ref. [82] presented how governments can use social media to analyze specific services and better understand their citizenry’s opinion (i.e., positive, negative, or neutral) of those services. Additionally, ref. [87] presented a system that uses social media data to identify trending views and influential citizens.

Multiple

Finally, looking specifically at the thirteen studies [95][96][97][98][99][100][101][102][103][104][105][106][107] that focused on the use of multiple approaches to identify urban problems (i.e., the fourth subcategory related to citizen participation in the identification of urban problems), two articles [96][104] presented generic tools (Figure 1): ref. [96] presented a middleware that allows the collection of data from multiple sources, be they static sensors, participatory sensing by citizens or data mined from social media, while [104] presented an application that allows citizens to report city problems and collect data through smartphone sensors. The remainder eleven studies [95][97][98][99][100][101][102][103][105][106][107] focused on specific issues: maintenance of the urban infrastructures [98][100][101][106], accessibility and mobility in the urban spaces [95][97][99][102], air and acoustic pollution [103], acoustic planning [107], and creation of a data repository [105] (Figure 1).

In what concerns the maintenance of urban infrastructures, namely the maintenance of roads potholes, ref. [106] presented an application that uses data mining of public data on Twitter together with data provided by a mobile application to allow citizens to report any potholes they find, including data about the hole (e.g., depth, diameter, or damage) along with its geolocation. In turn, ref. [98] presented an application that supported an urban data challenge to allow young citizens to document and reflect on their city problems through photos, videos, interviews, and posts from Facebook and Twitter. Moreover, the application presented by [100] aims to allow citizens to perform tasks to monitor urban services using participatory reporting and participatory sensing. Additionally, ref. [101] presented a unified framework to use different data sources, including data from social media and reports or measurements provided by the citizens.

Regarding accessibility and mobility in urban spaces, two studies [95][97] focused on the mobility of impaired people. Article [95] presented an application that uses participatory reporting, participatory sensing, and city open data to create tailored routes for citizens with mobility impairments, considering a routing algorithm that takes accessibility barriers as constraints. In turn, ref. [97] presented an application to promote urban accessibility by having citizens, both with and without disabilities, using wearable sensors to collect their movement patterns, which are processed to identify the routes that are not used by citizens with disabilities.

Still, in terms of mobility in the urban spaces, ref. [102] presented an application that aims to use both crowdsourced geodata from citizen reports and data gathered from Twitter to predict events that are likely to happen the next day in the same geographical area, while [99] presented a participatory sensing application to assess trip quality when riding in a vehicle. This application collects data from sensors and allows the citizens to report specific situations, and the aggregate data are analyzed to determine road or traffic quality [99].

Knowing that smart cities might reduce pollution levels if pollution sources are identified, ref. [103] presented an application to measure air pollution and noise levels in a city using multiple inputs: a network of high-precision static nodes, lower-precision mobile nodes, microphones of mobile devices to gather random noise samples, open access data sources, and citizen participation by answering questionnaires about air quality and noise levels. In turn, considering that the sounds of an area and how they impact people’s lives can be unintentionally neglected when designing urban environments, ref. [107] presented an application composed of multiple software tools to allow citizens to collect soundscapes and to provide reports to be used as part of the process of planning and designing urban environments, which is more commonly focused on the visual elements.

Concerning the creation of data repositories, ref. [105] proposed an application that allows various types of stakeholders (e.g., citizens, government, or companies) to collect data about a city from various sources (e.g., citizen reporting, dedicated sensors, or social networks), to be shared and visualized in several ways (e.g., 3D renders, heatmaps or lists).

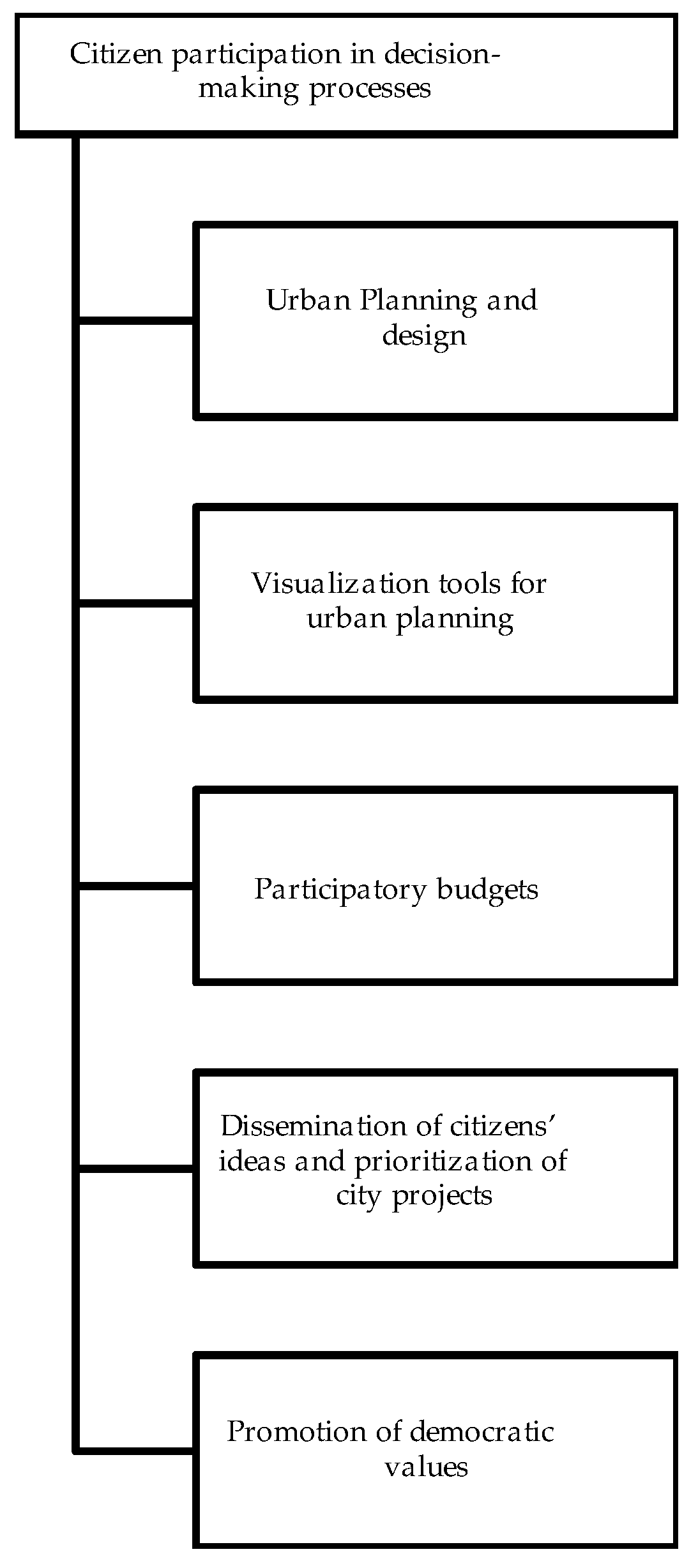

2. Citizen Participation in Decision-Making Processes

When planning and designing urban environments, the citizens living and working in those environments are the most affected. Therefore, it is an objective for smart cities to have citizens involved in the governance processes. In this respect, different types of collaborative applications were identified (Figure 2) to (1) support citizen participation in urban planning and design; (2) provide visualization tools for urban planning; (3) allow participatory budgets; (4) allow the dissemination of the citizen ideas and prioritization of city projects considering citizen satisfaction; and (5) promote democratic values including the transparency of public administration.

Figure 2. Types of collaborative approaches related to citizen participation in decision-making processes.

Six studies [108][109][110][111][112][113] focused on collaborative applications for citizen participation in urban planning. Article [108] presented an application designed to give the common person the tools and knowledge necessary to create and orchestrate citizen participatory reporting and sensing campaigns based on a six phases process: identification of issues, framing those issues in the existing context, design, deployment, orchestration of the finished product, and outcome review. In turn, collaborative applications to support city decision-making were presented by [109][113]. Moreover, refs. [110][111] presented applications to allow citizens and government officials to share information between themselves, and [112] proposed an application for the co-creation of neighborhoods by allowing the collaboration between citizens, and between citizens and the municipalities for the design and approval of houses, public spaces, renting spaces or other situations where government officials would also need the collaboration of the citizens.

Since it can be hard to extract information from large volumes of data, four studies [114][115][116][117] focused on applications providing visualization tools to allow citizens, both experts and non-experts, to better understand the repositories containing data related to urban planning: ref. [115] presented a tool to facilitate the visualization of data collected by city governments on several topics (e.g., pollution, attractiveness of surroundings, or resource management), and to allow citizens to give feedback on the data presented and services available; ref. [116] presented the Quick Urban Analysis Kit, which aims at the design of urban spaces by the citizens[117] presented a serious game to allow citizens to collaborate in constructing a smart city; and [114] presented a mixing panoramic imaging and architectural drawing tool for future urban plans.

Regarding participatory budgets, ref. [118] presented an application to allow citizens to propose projects to be funded and implemented. In turn, ref. [119] described an application to prioritize city projects considering citizen satisfaction according to various metrics. Finally, ref. [120] presented an application to allow citizens to present ideas for the benefit of the cities and comment and vote on ideas already posted. To incentivize citizen participation, competitions might be considered to distribute prizes such as gift certificates [120].

Four studies [121][122][123][124] focused on applications to promote democratic values and scrutinize public authorities’ decisions. Article [121] described the Visor Urbano application, which aims to lower city governments’ corruption by allowing citizens to request permits for building, opening businesses and other licenses. In turn, ref. [122] described an application to help identify misuse of resources and corruption in public works, allowing citizens to view the details of public works and report any inaccuracies or suspicious details they found to the government. Moreover, two articles [123][124] presented applications to provide the discussion and review of governmental policies: the applications for urban democracy that were implemented in Madrid and Barcelona were presented by [123]. In contrast, ref. [124] presented a government petition application of Taiwan that allows citizens to propose petitions if they reach the threshold of 5000 signatures in 60 days. Since the application has been in service since 2015, several proposed petitions have been implemented into policy.

3. Data Sources, Data Quality, Data Security and Privacy, and Strategies to Incentivize Citizen Participation

In terms of data sources, 25 studies focused on participatory reporting [49][50][51][52][53][54][55][56][57][58][59][60][61][62][63][64][65][66][67][68][69][70][71][72][73] and in other 12 studies [90][95][97][98][99][100][101][102][104][105][106][107] participatory reporting was used together with other approaches, such as participatory sensing or citizen-centered data analysis.

In turn, 19 studies (Table 1) implemented participatory sensing applications that use the sensors from personal mobile devices to collect data related to location, activity, and environment.

Table 1. Types of data acquired by personal sensors.

| Types of Sensors | Location | Activity | Environment | Not Specified |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smartphones’ sensors | ||||

| Unspecified | [50][52][74][75][76][107] | [74][95] | [80][107] | [49][70][75][76][77][78][96][99][100] |

| Microphones | [103] | |||

| Gyroscopes and accelerometers | [74] | |||

| Global Positioning System (GPS) | [52][66][79][80][97] | |||

| Wearables | ||||

| Body Area Network | [62] |

Furthermore, fourteen studies [81][82][83][84][85][86][87][88][89][90][91][92][93][94] were exclusively focused on the analysis of social media data (e.g., Facebook or Twitter), while seven other studies [96][98][100][101][102][105][106] combined the analysis of social media data with participatory reporting and participatory sensing.

In terms of data sources, one article [95] referred to the use of open data about real-time public transportation means (i.e., available equipment and respective accessibility barriers and facilitators), while another article [103] referred the use of open access data sources and a network composed by high precision static nodes and lower precision mobile nodes in addition to the microphones of the citizen mobile devices and answers to questionnaires about air quality and noise levels.

Since different heterogeneous data sources were considered, there is the possibility of contradictory data or data with low quality (e.g., missing values or outliers). Therefore, analyzing data quality and minimizing the consequences of low-quality data are relevant processes to be considered. However, just four articles reported how low-quality data are managed: the low-quality or incomplete data are filtered out by a classifier [50]; the open data collected from various sources were cleaned to eliminate corrupt and duplicate data, and standardized into a homogenous format, with the sources themselves checked for consistency [115]; the most extreme five percent of data records (best and worst) were ignored during evaluations, and the same ride trips were compared to each other to identify and correct abnormal readings [99]; data collected from multiple sources were verified for validity, outlier detection and missing values [103].

The applications reported by the included studies can potentially put the participants’ privacy at risk, namely in terms of the communication of personal data. Therefore, secure data transmission and storage must be guaranteed. However, only 10 articles [53][60][72][75][78][97][99][100][102][103] referred data security and privacy mechanisms or the usage of security frameworks: in the study presented by [60] auditing mechanisms were used to reinforce access control mechanisms[75] reported the implementation of a privacy module to allow the citizens to manage the data collection and to prevent unauthorized accesses; the study reported by [53] used OpenStack services and Spring Security framework[97] presented a method to preserve anonymity with Radio Frequency Identification (RFID); in the study reported by [78] the data transmitted was encrypted using the Advanced Encryption Standard (AES)[99] summarized several methods to handle privacy issues in participatory sensing applications; the study reported by [100] implemented a location obfuscation mechanism; in [102] is mentioned as a future work the mitigation of denial of service attacks; in the study reported by [72] the Secure Sockets Layer (SSL) protocol is used to encrypt data to be transmitted or stored; and [103] presented a method that allows recognizing environmental sounds while speech intelligibility is masked.

In addition to potential privacy risks, citizen participation requires consuming their resources, such as battery and computing power. Therefore, since the impact and relevance of participation campaigns depend on the engagement of the citizens, incentive mechanisms might be proposed, which can be either monetary or non-monetary (e.g., entertainment). To guarantee the engagement of the citizens, 19 of the included articles [50][52][54][55][56][64][65][66][71][74][77][78][96][99][100][103][117][120][123] reported the need to implement incentive mechanisms. However, only four of them [55][64][66][117] reported the use of gaming mechanisms and the other four [50][56][71][99] implemented incentive mechanisms considering different approaches: in [50], incentives were evaluated empirically to ascertain which one is better in which conditions to promote citizen participation; in [99], the various stakeholders gained benefits from the data collected; in [56], every performed action gained points for a ranking system, and in [71], the participants were awarded with a civic currency that can be traded by assets provided by sponsors.

References

- Pavlik, A. Examining the Relationship Between People and Government; California State University—Maritime Academy: Vallejo, CA, USA, 2019.

- Speer, J. Participatory Governance Reform: A Good Strategy for Increasing Government Responsiveness and Improving Public Services? World Dev. 2012, 40, 2379–2398.

- Bhargava, V. Engaging Citizens and Civil Society to Promote Good Governance and Development Effectiveness; Asian Development Bank: Mandaluyong, Philippines, 2015.

- Roberts, N.C. The Age of Direct Citizen Participation; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; ISBN 978-1-317-45881-4.

- Vigoda-Gadot, E.; Mizrahi, S. Managing Democracies in Turbulent Times: Trust, Performance, and Governance in Modern States; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; p. 199.

- Markoff, J. Democracy’s Past Transformations, Present Challenges, and Future Prospects. Int. J. Sociol. 2013, 43, 13–40.

- Gracia, D.B.; Casaló Ariño, L.V. Rebuilding Public Trust in Government Administrations through E-Government Actions. Rev. Española Investig. Mark. ESIC 2015, 19, 1–11.

- Amsler, L.; Nabatchi, T.; O’Leary, R. The New Governance: Practices and Processes for Stakeholder and Citizen Participation in the Work of Government. Public Adm. Rev. 2005, 65, 547–558.

- Sahamies, K.; Haveri, A.; Anttiroiko, A.-V. Local Governance Platforms: Roles and Relations of City Governments, Citizens, and Businesses. Adm. Soc. 2022, 54, 00953997211072531.

- Prabhu, C.S.R. E-Governance: Concepts and Cases Studies; PHI Learning Pvt. Ltd.: Delhi, India, 2013; ISBN 978-81-203-4557-7.

- Manoharan, A.P.; Ingrams, A. Conceptualizing E-Government from Local Government Perspectives. State Local Gov. Rev. 2018, 50, 56–66.

- Evans, D.; Yen, D.C. E-Government: Evolving Relationship of Citizens and Government, Domestic, and International Development. Gov. Inf. Q. 2006, 23, 207–235.

- Giffinger, R.; Fertner, C.; Kramar, H.; Kalasek, R.; Milanović, N.; Meijers, E. Smart Cities—Ranking of European Medium-Sized Cities; Vienna University of Technology: Vienna, Austria, 2007.

- Giffinger, R.; Gudrun, H. Smart Cities Ranking: An Effective Instrument for the Positioning of the Cities? ACE Archit. City Environ. 2010, 4, 7–26.

- Kirimtat, A.; Krejcar, O.; Kertesz, A.; Tasgetiren, M.F. Future Trends and Current State of Smart City Concepts: A Survey. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 86448–86467.

- Hollands, R. Will the Real Smart City Please Stand Up? City 2008, 12, 303–320.

- Caragliu, A.; Del Bo, C.; Nijkamp, P. Smart Cities in Europe. J. Urban Technol. 2011, 18, 65–82.

- Manville, C.; Europe, R.; Millard, J.; Cochrane, G.; Jonathan, C.A.V.E.; Pederson, J.K.; Thaarup, R.K.; WiK, M.W. Mapping Smart Cities in the EU; European Parliament—Directorate General for Internal Policies: London, UK, 2014.

- Prasad, D.; Alizadeh, T. What Makes Indian Cities Smart? A Policy Analysis of Smart Cities Mission. Telemat. Inform. 2020, 55, 101466.

- Albino, V.; Berardi, U.; Dangelico, R.M. Smart Cities: Definitions, Dimensions, Performance, and Initiatives. J. Urban Technol. 2015, 22, 3–21.

- Cavada, M.; Hunt, D.; Rogers, C. Smart Cities: Contradicting Definitions and Unclear Measures. 2014. Available online: https://sciforum.net/manuscripts/2454/manuscript.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2022).

- Kong, X.; Liu, X.; Jedari, B.; Li, M.; Wan, L.; Xia, F. Mobile Crowdsourcing in Smart Cities: Technologies, Applications, and Future Challenges. IEEE Internet Things J. 2019, 6, 8095–8113.

- Srivastava, P.; Mostafavi, A. Challenges and Opportunities of Crowdsourcing and Participatory Planning in Developing Infrastructure Systems of Smart Cities. Infrastructures 2018, 3, 51.

- Shahrour, I.; Xie, X. Role of Internet of Things (IoT) and Crowdsourcing in Smart City Projects. Smart Cities 2021, 4, 1276–1292.

- Alhalabi, W.; Lytras, M.; Aljohani, N. Crowdsourcing Research for Social Insights into Smart Cities Applications and Services. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7531.

- Alizadeh, T. Crowdsourced Smart Cities versus Corporate Smart Cities. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2018, 158, 012046.

- Berntzen, L.; Johannessen, M.; Böhm, S.; Weber, C.; Morales, R. Citizens as Sensors Human Sensors as a Smart City Data Source. In Proceedings of the SMART 2018—The Seventh International Conference on Smart Systems, Devices and Technologies, Barcelona, Spain, 22–26 July 2018; pp. 11–18.

- Ye, X.; Jourdan, D.; Lee, C.; Newman, G.; Van Zandt, S. Citizens as Sensors for Small Communities. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2021, 41, 374.

- L’Her, G.; Servières, M.; Siret, D. Citizen as Sensors’ Commitment in Urban Public Action: Case Study on Urban Air Pollution. Int. J. E-Plan. Res. 2022, 8, 42–59.

- Arayankalam, J.; Khan, A.; Krishnan, S. How to Deal with Corruption? Examining the Roles of e-Government Maturity, Government Administrative Effectiveness, and Virtual Social Networks Diffusion. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 58, 102203.

- Vaitkienė, D.; Juknevičienė, V.; Poškuvienė, B. The Usage of Social Networks for Citizen Engagement at the Local Self-Government Level: The Link between Municipal Councillors and Citizens. In Forum Scientiae Oeconomia; WSB University: Poznań, Poland, 2021; Volume 9, pp. 111–130.

- Alqaryouti, O.; Siyam, N.; Abdel Monem, A.; Shaalan, K. Aspect-Based Sentiment Analysis Using Smart Government Review Data. Appl. Comput. Inform. 2020, 16, 1–20.

- Leelavathy, S.; Nithya, M. Public Opinion Mining Using Natural Language Processing Technique for Improvisation towards Smart City. Int. J. Speech Technol. 2021, 24, 561–569.

- Shelton, T.; Lodato, T. Actually Existing Smart Citizens: Expertise and (Non)Participation in the Making of the Smart City. City 2019, 23, 35–52.

- Council of Europe. Civil Participation in Decision-Making; Council of Europe: London, UK, 2016.

- Marzuki, A. Challenges in the Public Participation and the Decision Making Process. Sociol. Prost. 2015, 53, 21–39.

- Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe. Implementing Citizens Participation in Decision Making at Local Level; Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe: Helsinki, Finland, 2016.

- Šabović, M.T.; Milosavljevic, M.; Benkovic, S. Participation of Citizens in Public Financial Decision-Making in Serbia. Slovak J. Political Sci. 2021, 21, 209–229.

- Gherghina, S.; Tap, P. Ecology Projects and Participatory Budgeting: Enhancing Citizens’ Support. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10561.

- Temeljotov Salaj, A.; Gohari, S.; Senior, C.; Xue, Y.; Lindkvist, C. An Interactive Tool for Citizens’ Involvement in the Sustainable Regeneration. Facilities 2020, 38, 859–870.

- Simonofski, A.; Serral Asensio, E.; De Smedt, J.; Snoeck, M. Hearing the Voice of Citizens in Smart City Design: The CitiVoice Framework. Bus. Inf. Syst. Eng. 2019, 61, 665–678.

- Mansoor, M. Citizens’ Trust in Government as a Function of Good Governance and Government Agency’s Provision of Quality Information on Social Media during COVID-19. Gov. Inf. Q. 2021, 38, 101597.

- Kim, S.K.; Park, M.J.; Rho, J.J. Does Public Service Delivery through New Channels Promote Citizen Trust in Government? The Case of Smart Devices. Inf. Technol. Dev. 2019, 25, 604–624.

- Hennen, L.; van Keulen, I.; Korthagen, I.; Aichholzer, G.; Lindner, R.; Nielsen, R.Ø. European E-Democracy in Practice; Studies in Digital Politics and Governance; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; ISBN 978-3-030-27183-1.

- Siyam, N.; Alqaryouti, O.; Abdallah, S. Mining Government Tweets to Identify and Predict Citizens Engagement. Technol. Soc. 2020, 60, 101211.

- Cortés-Cediel, M.; Cantador, I.; Rodríguez Bolívar, M.P. Analyzing Citizen Participation and Engagement in European Smart Cities. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2019, 39, 592–626.

- Preston, S.; Mazhar, M.U.; Bull, R. Citizen Engagement for Co-Creating Low Carbon Smart Cities: Practical Lessons from Nottingham City Council in the UK. Energies 2020, 13, 6615.

- Muñoz, L.; Rodríguez Bolívar, M.P. Using Tools for Citizen Engagement on Large and Medium-Sized European Smart Cities. In Public Administration and Information Technology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 23–35. ISBN 978-3-319-89473-7.

- Barrón, J.P.G.; Manso, M.Á.; Alcarria, R.; Pérez Gómez, R. A Mobile Crowdsourcing Platform for Urban Infrastructure Maintenance. In Proceedings of the 2014 Eighth International Conference on Innovative Mobile and Internet Services in Ubiquitous Computing, Birmingham, UK, 2–4 July 2014; pp. 358–363.

- Mukherjee, T.; Chander, D.; Mondal, A.; Dasgupta, K.; Kumar, A.; Venkat, A. CityZen: A Cost-Effective City Management System with Incentive-Driven Resident Engagement. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE 15th International Conference on Mobile Data Management, Brisbane, QLD, Australia, 14–18 July 2014; Volume 1, pp. 289–296.

- You, L.; Motta, G.; Liu, K.; Ma, T. A Pilot Crowdsourced City Governance System: CITY FEED. In Proceedings of the IEEE 17th International Conference on Computational Science and Engineering, Washington, DC, USA, 19–21 December 2014; pp. 1514–1519.

- Sakamura, M.; Ito, T.; Tokuda, H.; Yonezawa, T.; Nakazawa, J. MinaQn: Web-Based Participatory Sensing Platform for Citizen-Centric Urban Development. In Proceedings of the Adjunct Proceedings of the 2015 ACM International Joint Conference on Pervasive and Ubiquitous Computing and Proceedings of the 2015 ACM International Symposium on Wearable Computers, Osaka, Japan, 7 September 2015; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 1607–1614.

- Reforgiato Recupero, D.; Castronovo, M.; Consoli, S.; Costanzo, T.; Gangemi, A.; Grasso, L.; Lodi, G.; Merendino, G.; Mongiovì, M.; Presutti, V.; et al. An Innovative, Open, Interoperable Citizen Engagement Cloud Platform for Smart Government and Users’ Interaction. J. Knowl. Econ. 2016, 7, 388–412.

- Ariya Sanjaya, I.M.; Supangkat, S.H.; Sembiring, J. Citizen Reporting Through Mobile Crowdsensing: A Smart City Case of Bekasi. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on ICT for Smart Society (ICISS), West Java, Indonesia, 10–12 October 2018; pp. 1–4.

- Puritat, K. A Gamified Mobile-Based Approach with Web Monitoring for a Crowdsourcing Framework Designed for Urban Problems Related Smart Government: A Case Study of Chiang Mai, Thailand. Int. J. Interact. Mob. Technol. 2019, 13, 55–66.

- Barbosa, J.L.V. A Model for Resource Management in Smart Cities Based on Crowdsourcing and Gamification. JUCS—J. Univers. Comput. Sci. 2019, 25, 1018–1038.

- Falcão, A.; Wanderley, P.; Leite, T.; Baptista, C.; Queiroz, J.; Oliveira, M.; Rocha, J. Crowdsourcing Urban Issues in Smart Cities: A Usability Assessment of the Crowd4City System. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Electronic Government and the Information Systems Perspective, Linz, Austria, 26–29 August 2019; pp. 147–159.

- Marzano, G.; Lubkina, V. CityBook: A Mobile Crowdsourcing and Crowdsensing Platform. In Proceedings of the Future of Information and Communication Conference, San Francisco, CA, USA, 5–6 March 2020; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 420–431.

- Benouaret, K.; Valliyur-Ramalingam, R.; Charoy, F. CrowdSC: Building Smart Cities with Large-Scale Citizen Participation. IEEE Internet Comput. 2013, 17, 57–63.

- Bhana, B.; Flowerday, S.; Satt, A. Using Participatory Crowdsourcing in South Africa to Create a Safer Living Environment. Int. J. Distrib. Sens. Netw. 2013, 9, 907196.

- Luís, L.P.; Santos, T.M.P.; da Vendeirinho, S.P.S. Geoestrela: The next Generation Platform for Reporting Non-Emergency Issues-Borough Context. In Proceedings of the IADIS Multi Conference on Computer Science and Information Systema, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain, 21–24 July 2015; pp. 206–210.

- Rahman, M.A. A Framework to Support Massive Crowd: A Smart City Perspective. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Multimedia Expo Workshops (ICMEW), Seattle, WA, USA, 11–15 July 2016; pp. 1–6.

- Cortellazzi, J.; Foschini, L.; De Rolt, C.R.; Corradi, A.; Neto, C.A.A.; Alperstedt, G.D. Crowdsensing and Proximity Services for Impaired Mobility. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Symposium on Computers and Communication (ISCC), Messina, Italy, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 44–49.

- Froeschle, N.; Rieth, R.; Epple, J. Elektr-O-Mat—A Participation Game to Match and Explore the Relationship between Mobility and Citizens’ Needs. In Proceedings of the eChallenges e-2015 Conference, Vilnius, Lithuania, 25–26 November 2015; pp. 1–10.

- Lee, C.S.; Anand, V.; Han, F.; Kong, X.; Goh, D. Investigating the Use of a Mobile Crowdsourcing Application for Public Engagement in a Smart City. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Asian Digital Libraries, Tsukuba, Japan, 7 December 2016; pp. 98–103.

- Bousios, A.; Gavalas, D.; Lambrinos, L. CityCare: Crowdsourcing Daily Life Issue Reports in Smart Cities. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Symposium on Computers and Communications (ISCC), Heraklion, Greece, 3–6 July 2017; pp. 266–271.

- Seo-young, J.; Jung-ho, Y. A Study of the Classification of Crowd Types to Build Crowd-Sourcing-Based GIS. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 401, 012026.

- Kersting, N.; Zhu, Y. Crowd Sourced Monitoring in Smart Cities in the United Kingdom. In Proceedings of the Third International Conference, DTGS 2018, St. Petersburg, Russia, 30 May–2 June 2018; Revised Selected Papers, Part I. pp. 255–265.

- Chouikh, A. HandYwiN: A Crowdsourcing-Mapping Solution Towards Accessible Cities. In Proceedings of the 19th Annual International Conference on Digital Government Research: Governance in the Data Age, Delft, The Netherlands, 30 May 2018.

- Ham, H.; Teng, M.; Wijaya, E.; Wikopratama, R. Integration Citizen’ Suggestion System for the Urban Development: Tangerang City Case. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2018, 135, 570–578.

- Cerioli, M.; Ribaudo, M. Civic Participation Powered by Ethereum: A Proposal. In Proceedings of the Conference Companion of the 3rd International Conference on Art, Science, and Engineering of Programming, Oxford, UK, 1 April 2019; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 1–6.

- Chavez, C.V.; Ruiz, E.; Rodriguez, A.G.; Pena, I.R.; Larios, V.M.; Villanueva-Rosales, N.; Mondragon, O.; Cheu, R.L. Towards Improving Safety in Urban Mobility Using Crowdsourcing Incident Data Collection. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Smart Cities Conference (ISC2), Casablanca, Morocco, 14–17 October 2019; pp. 626–631.

- Shoemaker, E.; Randolph, H.; Bryce, J.; Narman, H.S. Designing Crowdsourcing Software to Inform Municipalities About Infrastructure Condition. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 18th International Conference on Smart Communities: Improving Quality of Life Using ICT, IoT and AI (HONET), Karachi, Pakistan, 11–13 October 2021; pp. 38–43.

- Cardone, G.; Foschini, L.; Bellavista, P.; Corradi, A.; Borcea, C.; Talasila, M.; Curtmola, R. Fostering Participaction in Smart Cities: A Geo-Social Crowdsensing Platform. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2013, 51, 112–119.

- Franke, T.; Lukowicz, P.; Blanke, U. Smart Crowds in Smart Cities: Real Life, City Scale Deployments of a Smartphone Based Participatory Crowd Management Platform. J. Internet Serv. Appl. 2015, 6, 27.

- Diniz, H.; Silva, E.; Nogueira, T.; Gama, K. A Reference Architecture for Mobile Crowdsensing Platforms. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2016), Rome, Italy, 25–28 January 2016; Volume 2, pp. 600–607.

- Montori, F.; Bedogni, L.; Di Chiappari, A.; Bononi, L. SenSquare: A Mobile Crowdsensing Architecture for Smart Cities. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 3rd World Forum on Internet of Things (WF-IoT), Reston, VA, USA, 12–14 December 2016; pp. 536–541.

- Khoi, N.M.; Rodríguez-Pupo, L.E.; Casteleyn, S. Citizense—A Generic User-Oriented Participatory Sensing Framework. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Selected Topics in Mobile and Wireless Networking (MoWNeT), Avignon, France, 17–19 May 2017; pp. 1–8.

- de Buosi, M.A.; Cilloni, M.; Corradi, A.; Rolt, C.R.D.; da Silva Dias, J.; Foschini, L.; Montanari, R.; Zito, P. A Crowdsensing Campaign and Data Analytics for Assisting Urban Mobility Pattern Determination. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Symposium on Computers and Communications (ISCC), Natal, Brazil, 25–28 June 2018; pp. 224–229.

- Zamora, W.; Vera, E.; Calafate, C.T.; Cano, J.-C.; Manzoni, P. GRC-Sensing: An Architecture to Measure Acoustic Pollution Based on Crowdsensing. Sensors 2018, 18, 2596.

- Giatsoglou, M.; Chatzakou, D.; Gkatziaki, V.; Vakali, A.; Anthopoulos, L. CityPulse: A Platform Prototype for Smart City Social Data Mining. J. Knowl. Econ. 2016, 7, 344–372.

- Joseph, N.; Grover, P.; Rao, P.K.; Ilavarasan, P.V. Deep Analyzing Public Conversations: Insights from Twitter Analytics for Policy Makers. In Proceedings of the Digital Nations—Smart Cities, Innovation, and Sustainability; Kar, A.K., Ilavarasan, P.V., Gupta, M.P., Dwivedi, Y.K., Mäntymäki, M., Janssen, M., Simintiras, A., Al-Sharhan, S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 239–250.

- Li, M.; Ch’ng, E.; Chong, A.; See, S. The New Eye of Smart City: Novel Citizen Sentiment Analysis in Twitter. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Audio, Language and Image Processing (ICALIP), Shanghai, China, 11–12 July 2016; pp. 557–562.

- Boukchina, E.; Mellouli, S.; Menif, E. From Citizens to Decision-Makers: A Natural Language Processing Approach in Citizens’ Participation. Int. J. E-Plan. Res. (IJEPR) 2018, 7, 20–34.

- Pérez-delHoyo, R.; Mora, H.; Paredes, J. Using Social Network Data to Improve Planning and Design of Smart Cities. WIT Trans. Built Environ. 2018, 179, 171–178.

- Nuaimi, A.; Shamsi, A.; Shamsi, A.; Badidi, E. Social Media Analytics for Sentiment Analysis and Event Detection in Smart Cities. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Natural Language Computing (NATL 2018), Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 28–29 April 2018; pp. 57–64.

- Tenney, M.; Hall, G.B.; Sieber, R.E. A Crowd Sensing System Identifying Geotopics and Community Interests from User-Generated Content. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2019, 33, 1497–1519.

- Sayah, I.; Schnabel, M.A. Amplifying Citizens’ Voices in Smart Cities: An Application of Social Media Sentiment Analysis in Urban Sciences. In Proceedings of the 24th International Conference of the Association for Computer-Aided Architectural Design Research in Asia (CAADRIA), Wellington, New Zealand, 15–18 April 2019; Association for Computer-Aided Architectural Design Research in Asia (CAADRIA): Hong Kong, China, 2019; pp. 773–782.

- Alizadeh, T.; Sarkar, S.; Burgoyne, S. Capturing Citizen Voice Online: Enabling Smart Participatory Local Government. Cities 2019, 95, 102400.

- Varghese, C.; Varde, A.; Du, X. An Ordinance-Tweet Mining App to Disseminate Urban Policy Knowledge for Smart Governance. In Proceedings of the Conference on e-Business, e-Services and e-Society, Skukuza, Kruger National Park, South Africa, 6–8 April 2020; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 389–401.

- Long, Z.; Alharthi, R.; Saddik, A.E. NeedFull—A Tweet Analysis Platform to Study Human Needs During the COVID-19 Pandemic in New York State. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 136046–136055.

- Gao, Z.; Wang, S.; Gu, J. Public Participation in Smart-City Governance: A Qualitative Content Analysis of Public Comments in Urban China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8605.

- Parusheva, S.; Hadzhikolev, A. Social Media as a People Sensing for the City Government in Smart Cities Context. TEM J. 2020, 9, 55–66.

- Kim, B.; Yoo, M.; Park, K.C.; Lee, K.R.; Kim, J.H. A Value of Civic Voices for Smart City: A Big Data Analysis of Civic Queries Posed by Seoul Citizens. Cities 2021, 108, 102941.

- Mirri, S.; Prandi, C.; Salomoni, P.; Callegati, F.; Campi, A. On Combining Crowdsourcing, Sensing and Open Data for an Accessible Smart City. In Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on Next Generation Mobile Apps, Services and Technologies, Oxford, UK, 10–12 September 2014; pp. 294–299.

- Hachem, S.; Issarny, V.; Mallet, V.; Pathak, A.; Bhatia, R.; Raverdy, P.-G. Urban Civics: An IoT Middleware for Democratizing Crowdsensed Data in Smart Societies. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE 1st International Forum on Research and Technologies for Society and Industry Leveraging a Better Tomorrow (RTSI), Turin, Italy, 16–18 September 2015; pp. 117–126.

- Mora, H.; Gilart-Iglesias, V.; Pérez-del Hoyo, R.; Andújar-Montoya, M.D. A Comprehensive System for Monitoring Urban Accessibility in Smart Cities. Sensors 2017, 17, 1834.

- Ruiz-Correa, S.; Santani, D.; Ramírez-Salazar, B.; Ruiz-Correa, I.; Rendón-Huerta, F.A.; Olmos-Carrillo, C.; Sandoval-Mexicano, B.C.; Arcos-García, Á.H.; Hasimoto-Beltrán, R.; Gatica-Perez, D. SenseCityVity: Mobile Crowdsourcing, Urban Awareness, and Collective Action in Mexico. IEEE Pervasive Comput. 2017, 16, 44–53.

- Xiao, Z.; Lim, H.B.; Ponnambalam, L. Participatory Sensing for Smart Cities: A Case Study on Transport Trip Quality Measurement. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2017, 13, 759–770.

- Kandappu, T.; Misra, A.; Koh, D.; Tandriansyah, R.D.; Jaiman, N. A Feasibility Study on Crowdsourcing to Monitor Municipal Resources in Smart Cities. In Proceedings of the Companion Proceedings of the Web Conference 2018, Lyon, France, 23 April 2018; International World Wide Web Conferences Steering Committee: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 919–925.

- Chong, M.; Habib, A.; Evangelopoulos, N.; Park, H.W. Dynamic Capabilities of a Smart City: An Innovative Approach to Discovering Urban Problems and Solutions. Gov. Inf. Q. 2018, 35, 682–692.

- Witanto, J.N.; Lim, H.; Atiquzzaman, M. Smart Government Framework with Geo-Crowdsourcing and Social Media Analysis. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2018, 89, 1–9.

- Bardoutsos, A.; Filios, G.; Katsidimas, I.; Krousarlis, T.; Nikoletseas, S.; Tzamalis, P. A Multidimensional Human-Centric Framework for Environmental Intelligence: Air Pollution and Noise in Smart Cities. In Proceedings of the 2020 16th International Conference on Distributed Computing in Sensor Systems (DCOSS), Marina del Rey, CA, USA, 25–27 May 2020; pp. 155–164.

- Aljoufie, M.; Tiwari, A. Citizen Sensors for Smart City Planning and Traffic Management: Crowdsourcing Geospatial Data through Smartphones in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. GeoJournal 2021, 87, 3149–3168.

- Suciu, G.; Necula, L.-A.; Jelea, V.; Cristea, D.-S.; Rusu, C.-C.; Mistodie, L.-R.; Ivanov, M.-P. Smart City Platform Based on Citizen Reporting Services. In Advances in Industrial Internet of Things, Engineering and Management; Cagáňová, D., Horňáková, N., Pusca, A., Cunha, P.F., Eds.; EAI/Springer Innovations in Communication and Computing; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 87–100. ISBN 978-3-030-69705-1.

- Yudono, A.; Istamar, A. Citizen Potholes E-Report System as a Step to Use Big Data in Planning Smart Cities in Malang City, Indonesia. In Proceedings of the Resilient and Responsible Smart Cities; Ujang, N., Fukuda, T., Pisello, A.L., Vukadinović, D., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 139–151.

- Neuvonen, A.; Salo, K.; Mikkonen, T. Towards Participatory Design of City Soundscapes. In Proceedings of the Advances in Information and Communication; Arai, K., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 497–512.

- Balestrini, M.; Rogers, Y.; Hassan, C.; Creus, J.; King, M.; Marshall, P. A City in Common: A Framework to Orchestrate Large-Scale Citizen Engagement around Urban Issues. In Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Denver, CO, USA, 2 May 2017; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 2282–2294.

- Khan, Z.; Dambruch, J.; Peters-Anders, J.; Sackl, A.; Strasser, A.; Fröhlich, P.; Templer, S.; Soomro, K. Developing Knowledge-Based Citizen Participation Platform to Support Smart City Decision Making: The Smarticipate Case Study. Information 2017, 8, 47.

- De Filippi, F.; Coscia, C.; Guido, R. How Technologies Can Enhance Open Policy Making and Citizen-Responsive Urban Planning: MiraMap—A Governing Tool for the Mirafiori Sud District in Turin. Int. J. E-Plan. Res. 2017, 6, 23–42.

- Pereira, G.; Eibl, G.; Stylianou, C.; Martínez, G.; Neophytou, H.; Parycek, P. The Role of Smart Technologies to Support Citizen Engagement and Decision Making: The SmartGov Case. Int. J. Electron. Gov. Res. 2018, 14, 1–17.

- Recalde, L.; Jiménez-Pacheco, P.; Mendoza, K.; Meza, J. Collaboration-Based Urban Planning Platform: Modeling Cognition to Co-Create Cities. In Proceedings of the 2020 Seventh International Conference on eDemocracy eGovernment (ICEDEG), Buenos Aires, Argentina, 22–24 April 2020; pp. 80–86.

- Stelzle, B.; Jannack, A.; Holmer, T.; Naumann, F.; Wilde, A.; Noennig, J.R. Smart Citizens for Smart Cities—A User Engagement Protocol for Citizen Participation. In Proceedings of the Internet of Things, Infrastructures and Mobile Applications; Auer, M.E., Tsiatsos, T., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 571–581.

- Oksman, V.; Kulju, M. Developing Online Illustrative and Participatory Tools for Urban Planning: Towards Open Innovation and Co-Production through Citizen Engagement. Int. J. Serv. Technol. Manag. 2017, 23, 445–464.

- Gagliardi, D.; Schina, L.; Sarcinella, M.L.; Mangialardi, G.; Niglia, F.; Corallo, A. Information and Communication Technologies and Public Participation: Interactive Maps and Value Added for Citizens. Gov. Inf. Q. 2017, 34, 153–166.

- Mueller, J.; Lu, H.; Chirkin, A.; Klein, B.; Schmitt, G. Citizen Design Science: A Strategy for Crowd-Creative Urban Design. Cities 2018, 72, 181–188.

- Aguilar, J.; Díaz, F.; Altamiranda, J.; Cordero, J.; Chavez, D.; Gutierrez, J. Metropolis: Emergence in a Serious Game to Enhance the Participation in Smart City Urban Planning. J. Knowl. Econ. 2021, 12, 1594–1617.

- Gooch, D.; Barker, M.; Hudson, L.; Kelly, R.; Kortuem, G.; Linden, J.V.D.; Petre, M.; Brown, R.; Klis-Davies, A.; Forbes, H.; et al. Amplifying Quiet Voices: Challenges and Opportunities for Participatory Design at an Urban Scale. ACM Trans. Comput.-Hum. Interact. 2018, 25, 1–34.

- Ceballos, G.R.; Larios, V.M. A Model to Promote Citizen Driven Government in a Smart City: Use Case at GDL Smart City. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Smart Cities Conference (ISC2), Trento, Italy, 12–15 September 2016; pp. 1–6.

- Díaz-Díaz, R.; Pérez-González, D. Implementation of Social Media Concepts for E-Government: Case Study of a Social Media Tool for Value Co-Creation and Citizen Participation. JOEUC 2016, 28, 104–121.

- Arauz, M.R.; Moreno, Y.; Nancalres, R.; Pérez, C.V.; Larios, V.M. Tackling Corruption in Urban Development through Open Data and Citizen Empowerment: The Case of “Visor Urbano” in Guadalajara. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Smart Cities Conference (ISC2), Wuxi, China, 14–17 September 2017; pp. 1–4.

- Sagar, A.B.; Nagamani, M.; Banothu, R.; Babu, K.R.; Juturi, V.R.; Kothari, P. EGovernance for Citizen Awareness and Corruption Mitigation. In Proceedings of the Intelligent Human Computer Interaction; Singh, M., Kang, D.-K., Lee, J.-H., Tiwary, U.S., Singh, D., Chung, W.-Y., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 481–487.

- Smith, A.; Martín, P.P. Going Beyond the Smart City? Implementing Technopolitical Platforms for Urban Democracy in Madrid and Barcelona. J. Urban Technol. 2021, 28, 311–330.

- Hsin-Ying, H.; Mate, K.; Victor, K.; Uwe, S. Towards a Model of Online Petition Signing Dynamics on the Join Platform in Taiwan. In Proceedings of the 2021 Eighth International Conference on eDemocracy eGovernment (ICEDEG), Quito, Ecuador, 28–30 July 2021; pp. 199–204.

More

Information

Subjects:

Public Administration

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

2.1K

Revisions:

3 times

(View History)

Update Date:

07 Nov 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No