Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Xu, Y.; Ma, Q.; Du, H.; Yang, C.; Lin, G. Postoperative Delirium in Neurosurgical Patients. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/32275 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Xu Y, Ma Q, Du H, Yang C, Lin G. Postoperative Delirium in Neurosurgical Patients. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/32275. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Xu, Yinuo, Qianquan Ma, Haiming Du, Chenlong Yang, Guozhong Lin. "Postoperative Delirium in Neurosurgical Patients" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/32275 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Xu, Y., Ma, Q., Du, H., Yang, C., & Lin, G. (2022, November 01). Postoperative Delirium in Neurosurgical Patients. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/32275

Xu, Yinuo, et al. "Postoperative Delirium in Neurosurgical Patients." Encyclopedia. Web. 01 November, 2022.

Copy Citation

Postoperative delirium (POD) is a complication characterized by disturbances in attention, awareness, and cognitive function that occur shortly after surgery or emergence from anesthesia. Since it occurs prevalently in neurosurgical patients and poses great threats to the well-being of patients, much emphasis is placed on POD in neurosurgical units.

postoperative delirium

neurosurgery

cognitive dysfunction

1. Introduction

Delirium is a temporary mental dysfunction characterized by confusion, anxiety, incoherent speech, hallucinations, and reduced awareness of the environment [1]. Postoperative delirium (POD) is a common complication in patients who undergo hospitalization and surgery and occurs most often in the hospital up to 1 week after surgery or until discharge [2][3]. Elderly patients undergoing surgery are at the highest risk of developing POD [4]. More than half of the elderly patients who underwent abdominal surgery were reported to experience POD. Moreover, approximately 54.9% of patients over 70 years of age underwent cardiac surgery and 6–56% of the general hospitalized population had symptoms of delirium [1][5]. Certain anesthetic interventions have been found to be associated with an increased risk of POD; notably, 31% of patients emerging from anesthesia had signs of delirium in the post-anesthesia care unit [6].

Patients with POD are under the threat of physically harming themselves without awareness. Patients may experience damage to the intravenous lines and tear the wound dressing. Furthermore, increasing evidence indicates that POD could severely affect multiple aspects of patient health. POD is associated with increased mortality in patients after transcatheter aortic valve implantation, with a 1-year survival rate decreasing from 85% to 68% [7]. In a retrospective study involving 1260 patients undergoing cardiac surgery, patients with POD experienced significantly more frequent postoperative complications, such as myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular accidents, respiratory complications, and infections [8]. POD also results in other complications, such as a prolonged hospital stay, delayed functional recovery, and increased morbidity [9].

The management of POD is also particularly important in neurosurgical units. Among those patients undergoing intracranial surgery, 4.2% had serious POD, which is directly associated with impaired neurological function and extended rehabilitation [10]. A meta-analysis involving 5589 patients revealed that the incidence of POD after intracranial surgery ranges from 12% to 26% due to variations in clinical characteristics and delirium assessment methods [11].

2. Risk Factors

Randomized results have shown that the incidence of POD is related to various perioperative risk factors. Knowledge of risk factors can help in clinical decision making and the identification of high-risk patients. The risk factors correlated with the onset of delirium, such as type of anesthesia, age, preoperative cognitive function, neurological function, and environmental factors, are summarized.

2.1. Anesthesia

The effect of the different types of anesthesia on POD is controversial. In a previous study, regional anesthesia and analgesia did not show any benefit with respect to POD compared with general anesthesia [12]. Recently, emerging evidence has been published to provide additional information on this topic. Regional anesthesia, such as caudal block, fascia iliac compartment block, and intravertebral anesthesia, is also mentioned to reduce the incidence of POD [13][14][15]. A recent study used topological data analysis to assess the phenotypic subgroups of delirium and suggested that elderly patients are more susceptible to POD and that this influence may be amplified by regional anesthesia [16]. In a recent study, data showed that regional anesthesia significantly reduced POD incidence and severity. The positive effect of regional anesthesia was especially reflected in pediatric patients rather than elderly patients on postoperative days 1–5 [17]. In neurosurgical operations, a longer duration of anesthesia is expected to induce POD due to the impairment of neurons. Patients with anesthesia for more than 4 h showed a dramatically higher incidence of POD. Interestingly, a history of anesthesia did not affect the occurrence of POD [18].

2.2. Age

POD is the most common complication following surgery in elderly patients. The incidence of POD has been estimated to range from 4% to 53% following fracture surgery in the elderly [19]. It is hypothesized that the increased risk of imbalance in cortical neurotransmitters or inflammatory responses contributes to delirium. In spinal surgery, patients younger than 73 years had a significantly lower incidence of delirium. Older age, low preoperative cognitive function, longer duration of surgery, and transfusion are important risk factors for POD [20]. Similarly, older age is also a critical intrinsic predictor of POD in those patients undergoing transcranial surgery. One study included patients aged 14–80 years who underwent brain tumor resection. The mean age of patients without and with POD was 47.1 ± 14.28 and 51.9 ± 12.66, respectively [18].

2.3. Cognitive Condition

Patients who undergo surgery and anesthesia are also at high risk of temporary or permanent cognitive impairment due to acute stress. Mounting evidence suggests that delirium may lead to permanent cognitive decline and dementia in some patients. Cognitive impairment was common (>50%) in surgical patients who developed POD, and the impairment persisted up to 1-year postoperatively [21]. Consistently, the cognitive state before surgery is a strong predictor of POD occurrence. Previous cognitive dysfunction, such as dementia or neurodegenerative status, greatly increases the vulnerability to POD [22][23]. In elderly patients with dementia, delirium is associated with increased rates of cognitive decline, admission to institutions, and mortality [21].

2.4. Intrinsic and Extrinsic Factors

The development of POD is multifactorial. Despite its main etiological factors, multiple intrinsic and extrinsic elements also promote the progression of POD. POD in neurosurgery patients can be induced due to hypothalamic syndrome, infection, electrolyte disturbances, fever, and profuse urination. A longer duration of ICU patients’ stay in the ICU was also associated with a higher incidence of POD [18]. In particular, cardiac arrest is an additional predisposing factor for POD because most survivors of cardiac arrest are treated in the ICU. A longer stay in the ICU has been hypothesized to induce POD. The occurrence of delirium prolongs the duration of the ICU and hospital stay and adversely affects functional outcomes [24].

Surgeons and anesthesiologists are devoting great effort to the prediction of the occurrence and the minimization of the risk of POD. The monitoring of processed electroencephalograms (EEGs) is considered an alternative method to predict the occurrence of POD. One moderate-quality evidence study indicated that EEG-optimized anesthesia could reduce the risk of POD in those patients aged ≥ 60 years who underwent non-cardiac or non-neurosurgical procedures [25]. However, a more advanced study did not agree with this conclusion. They found that in older adults who underwent major surgery, EEG-guided anesthetic administration, compared with usual care, did not decrease the incidence of POD [26].

3. Pathological Theories

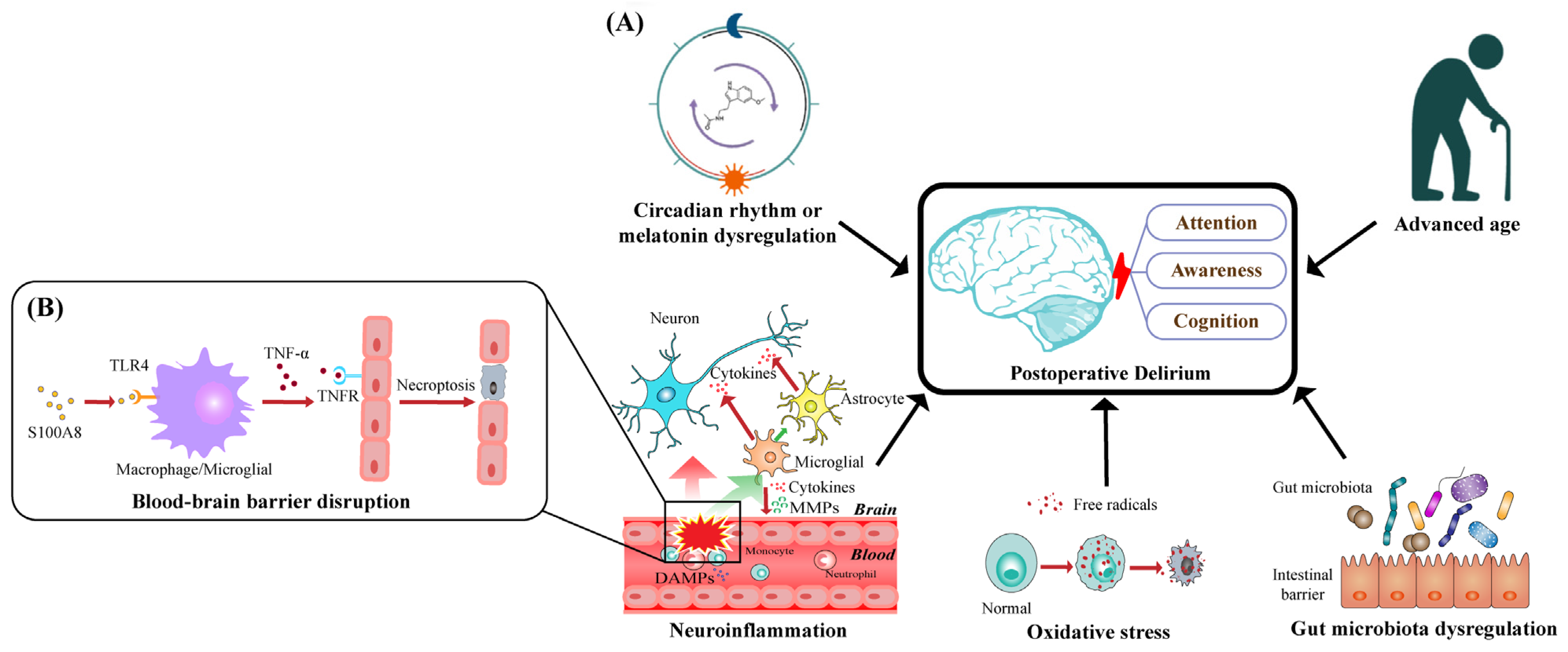

Taking recent insights into comprehensive consideration, researchers conclude with five dominant pathological theories, as illustrated in Figure 1A, which may explain the occurrence and development of POD characterized by disturbances in attention, awareness, and cognition.

Figure 1. Schematic diagram of pathological mechanisms underlying postoperative delirium: (A) five dominant pathological theories that may account for the occurrence and development of POD characterized by disturbances in attention, awareness, and cognition; (B) S100A8, as a main member of DAMPs, promotes the activation of TLR4 in macrophages and microglia and then increases the expression of TNF-α; TNF-α will bind to TNFR on endothelial cells, subsequently triggering their necroptosis, which disrupts BBB’s integrity and increases BBB’s permeability.

3.1. Neuroinflammation

Inflammation is inevitable after surgery as a protective response to injury. However, peripheral inflammation may trigger neuroinflammation, leading to the dysfunction of the central nervous system (CNS) and the subsequent neurobehavioral and cognitive symptoms of postoperative delirium. Additionally, inflammation from the periphery to the CNS starts with increased permeability of the blood–brain barrier (BBB).

The BBB is a highly regulated and maintained interface that separates the peripheral circulation from the CNS. A specific monolayer of endothelial cells, which forms the capillaries of the brain, is the main component of the BBB. Other components of the BBB anatomy include astrocytes, pericytes, neurons, and extracellular matrix [27][28].

Cellular injury caused by aseptic surgical trauma can induce the release of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) that activate the peripheral innate immune system [29]. S100A8 (Migration suppressor-associated protein-8 (MRP8)) is an important proinflammatory cytokine in many inflammatory conditions and is expressed in large quantities by activated neutrophils and monocytes [30][31]. As a main member of the DAMPs, S100A8 has been shown to promote the activation of Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) in macrophages and microglia [32][33][34]. In the TLR4 signaling pathway, MyD88 is an important activator of the NF-κB signaling pathway [35][36]. Previous studies have confirmed that S100A8 induced by surgery activates the TLR4/MyD88 pathway in mouse models [33]. A recent study in a rat model showed that S100A8/A9 binds to TLR4 and increases the expression of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), and IL-6 (interleukin-6) through the NF-κB signaling pathways in nucleus pulposus cells, which contributes to inflammation-related pain [37].

The upregulation of TNF-α has been widely detected in postoperative patients [38][39]. TNF-α secreted by activated microglia cells binds to the TNF receptor (TNFR) on endothelial cells, subsequently triggering necroptosis through receptor-interacting protein kinase 1 (RIPK1), RIPK3, and mixed-lineage kinase domain-like pseudo kinase (MLKL), which disrupts the integrity of BBB and increases the permeability of BBB [40][41], as illustrated in Figure 1B. Moreover, TNF-α induces the release of MMP-9 from pericytes, resulting in increased endothelial permeability in BBB models in vitro [42].

The proinflammatory cytokine IL-6 is significantly upregulated in patients after orthopedic surgery [38][39][43]. In mouse models, IL-6 disrupts the BBB and promotes hippocampal inflammation through bone marrow-derived monocytes [44].

Upon infiltration into the brain parenchyma through the BBB, peripheral factors such as DAMPs and cytokines can trigger downstream neuroinflammatory responses.

Microglial cells, which account for 20% of the total glial cell population of the brain, are the main components of the posterior gray and white matter [45] and function to monitor the well-being of their environment and maintain homeostasis through innate defense mechanisms or specific immune reactions [46]. In a normal CNS environment, microglia are shut down with a scarce expression of many typical proteins on the surface of other tissue macrophages [47][48]. The activation states of microglial cells can be divided into M1 (classic activation) triggered by interferon-γ and M2 (alternative activation), which are mainly triggered by the Th2 cytokines IL-4 and IL-13 [49][50][51]. Activated microglial cells have long been considered the main source of proinflammatory factors such as cytokines, eicosanoids, complement factors, excitatory amino acids, reactive oxygen radicals, and nitric oxide [46][52]. Furthermore, owing to the microglial-secreted cytokines, the neurotoxic reactive subtype of astrocytes, astrocytes, can be induced by classically activated microglial cells, which contribute to the death of neurons and oligodendrocytes [53].

A recent study showed that neuronal dysfunction after traumatic brain injury, including disrupted neuronal homeostasis, reduced dendritic complexity, and defective compound action potential, can be attenuated by microglial elimination [54]. Moreover, in those patients undergoing abdominal surgery, microglial activation has been detected and associated with impairments in cognitive function [54]. Meanwhile, the endogenous mesencephalic astrocyte-derived neurotrophic factor has been shown to have positive effects on POD by inhibiting surgery-induced inflammation and microglial activation [55][56].

3.2. Oxidative Stress

Oxidative stress is an imbalance between the production of oxidants in cells and tissues and the particular biological processes that trigger the detoxification of these reactive products [57]. Under physiological and pathological conditions, cells can produce free radicals and reactive oxygen species (ROS) through the NADPH–oxidase system, xanthine oxidase, and mitochondrial electron transport chain [58].

The disruption of the BBB is a common cause of oxidative stress. Rat brain microvascular endothelial cells exposed to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) at high concentrations display significant monolayer hyperpermeability with decreased cell viability and induced apoptosis [59]. It has been found that ROS can result in the BBB’s cytoskeleton rearrangement and redistribution and disappearance of tight junction (TJ) proteins, mediated by RhoA, PI3 kinase, and PKB signaling [60]. Occludin, a component of intercellular TJ protein complexes, moves away from TJ during oxidative stress [61]. Furthermore, toxic cell H2O2 concentrations cause occludin cleavage with the involvement of MMP-2 [62], and the upregulation of MMP-9 induces posttraumatic nerve and BBB injury, which may be partially mediated by Scube2 and SHH through the hedgehog pathway [63]. In turn, patients with increased disruption of the BBB are more vulnerable to neuronal injury induced by oxidative stress [64].

Oxidants have been found to increase the gating potential of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP), resulting in hypersensitivity to Ca2+ activation during neuronal oxidative stress [65]. The high permeability of the mitochondrial membrane induced by mPTP dysfunction not only impairs the mitochondrial electron transport chain but also causes mitochondrial swelling, consequently leading to the over-release of ROS and neuronal necrosis [66]. Cyclosporine A, an inhibitor of mPTP opening that suppresses oxidative stress [67][68], was found to attenuate delirium-like behavior induced by anesthesia and surgery, with decreased ROS levels in the hippocampus of POD-like mice [69]. Meanwhile, as an innate protective mechanism to combat invading pathogens, macrophage cell lines, including microglia, can produce superoxide radicals and nitric oxide, resulting in the production and spread of peroxynitrite [70]. Peroxynitrite has been shown to induce neuronal apoptosis through the intracellular release of zinc and subsequent activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and caspase 3 [71].

References

- Association, A.P. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®), 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association Publishing: Arlington, TX, USA, 2013.

- Evered, L.; Silbert, B.; Knopman, D.S.; Scott, D.A.; DeKosky, S.T.; Rasmussen, L.S.; Oh, E.S.; Crosby, G.; Berger, M.; Eckenhoff, R.G.; et al. Recommendations for the Nomenclature of Cognitive Change Associated with Anaesthesia and Surgery-2018. Anesthesiology 2018, 129, 872–879.

- Migirov, A.; Chahar, P.; Maheshwari, K. Postoperative delirium and neurocognitive disorders. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 2021, 27, 686–693.

- Olin, K.; Eriksdotter-Jonhagen, M.; Jansson, A.; Herrington, M.K.; Kristiansson, M.; Permert, J. Postoperative delirium in elderly patients after major abdominal surgery. Br. J. Surg. 2005, 92, 1559–1564.

- Smulter, N.; Lingehall, H.C.; Gustafson, Y.; Olofsson, B.; Engstrom, K.G. Delirium after cardiac surgery: Incidence and risk factors. Interact. Cardiovasc Thorac. Surg. 2013, 17, 790–796.

- Card, E.; Pandharipande, P.; Tomes, C.; Lee, C.; Wood, J.; Nelson, D.; Graves, A.; Shintani, A.; Ely, E.W.; Hughes, C. Emergence from general anaesthesia and evolution of delirium signs in the post-anaesthesia care unit. Br. J. Anaesth. 2015, 115, 411–417.

- Goudzwaard, J.A.; de Ronde-Tillmans, M.; de Jager, T.A.J.; Lenzen, M.J.; Nuis, R.J.; van Mieghem, N.M.; Daemen, J.; de Jaegere, P.P.T.; Mattace-Raso, F.U.S. Incidence, determinants and consequences of delirium in older patients after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Age Ageing 2020, 49, 389–394.

- Sugimura, Y.; Sipahi, N.F.; Mehdiani, A.; Petrov, G.; Awe, M.; Minol, J.P.; Boeken, U.; Korbmacher, B.; Lichtenberg, A.; Dalyanoglu, H. Risk and Consequences of Postoperative Delirium in Cardiac Surgery. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2020, 68, 417–424.

- Wu, J.; Gao, S.; Zhang, S.; Yu, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Z.; Mei, W. Perioperative risk factors for recovery room delirium after elective non-cardiovascular surgery under general anaesthesia. Perioper. Med. 2021, 10, 3.

- Budenas, A.; Tamasauskas, S.; Sliauzys, A.; Navickaite, I.; Sidaraite, M.; Pranckeviciene, A.; Deltuva, V.P.; Tamasauskas, A.; Bunevicius, A. Incidence and clinical significance of postoperative delirium after brain tumor surgery. Acta Neurochir. 2018, 160, 2327–2337.

- Kappen, P.R.; Kakar, E.; Dirven, C.M.F.; van der Jagt, M.; Klimek, M.; Osse, R.J.; Vincent, A. Delirium in neurosurgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosurg. Rev. 2022, 45, 329–341.

- Zhang, H.; Lu, Y.; Liu, M.; Zou, Z.; Wang, L.; Xu, F.Y.; Shi, X.Y. Strategies for prevention of postoperative delirium: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Crit. Care 2013, 17, R47.

- Weldon, B.C.; Bell, M.; Craddock, T. The effect of caudal analgesia on emergence agitation in children after sevoflurane versus halothane anesthesia. Anesth. Analg. 2004, 98, 321–326.

- Aouad, M.T.; Kanazi, G.E.; Siddik-Sayyid, S.M.; Gerges, F.J.; Rizk, L.B.; Baraka, A.S. Preoperative caudal block prevents emergence agitation in children following sevoflurane anesthesia. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 2005, 49, 300–304.

- Kim, H.S.; Kim, C.S.; Kim, S.D.; Lee, J.R. Fascia iliaca compartment block reduces emergence agitation by providing effective analgesic properties in children. J. Clin. Anesth. 2011, 23, 119–123.

- Shin, J.E.; Kyeong, S.; Lee, J.S.; Park, J.Y.; Lee, W.S.; Kim, J.J.; Yang, K.H. A personality trait contributes to the occurrence of postoperative delirium: A prospective study. BMC Psychiatry 2016, 16, 371.

- Li, T.; Dong, T.; Cui, Y.; Meng, X.; Dai, Z. Effect of regional anesthesia on the postoperative delirium: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front. Surg. 2022, 9, 937293.

- Chen, H.; Jiang, H.; Chen, B.; Fan, L.; Shi, W.; Jin, Y.; Ren, X.; Lang, L.; Zhu, F. The Incidence and Predictors of Postoperative Delirium after Brain Tumor Resection in Adults: A Cross-Sectional Survey. World Neurosurg. 2020, 140, e129–e139.

- Rizk, P.; Morris, W.; Oladeji, P.; Huo, M. Review of Postoperative Delirium in Geriatric Patients Undergoing Hip Surgery. Geriatr. Orthop. Surg. Rehabil. 2016, 7, 100–105.

- Kang, T.; Park, S.Y.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, S.H.; Park, J.H.; Kim, S.K.; Suh, S.W. Incidence & Risk Factors of Postoperative Delirium after Spinal Surgery in Older Patients. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 9232.

- Inouye, S.K.; Westendorp, R.G.; Saczynski, J.S. Delirium in elderly people. Lancet 2014, 383, 911–922.

- Gross, A.L.; Jones, R.N.; Habtemariam, D.A.; Fong, T.G.; Tommet, D.; Quach, L.; Schmitt, E.; Yap, L.; Inouye, S.K. Delirium and Long-term Cognitive Trajectory among Persons with Dementia. Arch. Intern. Med. 2012, 172, 1324–1331.

- Fong, T.G.; Jones, R.N.; Marcantonio, E.R.; Tommet, D.; Gross, A.L.; Habtemariam, D.; Schmitt, E.; Yap, L.; Inouye, S.K. Adverse outcomes after hospitalization and delirium in persons with Alzheimer disease. Ann. Intern. Med. 2012, 156, 848–856, W296.

- Medrzycka-Dabrowska, W.; Lange, S.; Religa, D.; Dabrowski, S.; Friganovic, A.; Oomen, B.; Krupa, S. Delirium in ICU Patients after Cardiac Arrest: A Scoping Review. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 1047.

- Punjasawadwong, Y.; Chau-In, W.; Laopaiboon, M.; Punjasawadwong, S.; Pin-On, P. Processed electroencephalogram and evoked potential techniques for amelioration of postoperative delirium and cognitive dysfunction following non-cardiac and non-neurosurgical procedures in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 5, CD011283.

- Wildes, T.S.; Mickle, A.M.; Ben Abdallah, A.; Maybrier, H.R.; Oberhaus, J.; Budelier, T.P.; Kronzer, A.; McKinnon, S.L.; Park, D.; Torres, B.A.; et al. Effect of Electroencephalography-Guided Anesthetic Administration on Postoperative Delirium among Older Adults Undergoing Major Surgery: The ENGAGES Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2019, 321, 473–483.

- Obermeier, B.; Daneman, R.; Ransohoff, R.M. Development, maintenance and disruption of the blood-brain barrier. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 1584–1596.

- Abbott, N.J.; Ronnback, L.; Hansson, E. Astrocyte-endothelial interactions at the blood-brain barrier. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2006, 7, 41–53.

- Matzinger, P. Tolerance, danger, and the extended family. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1994, 12, 991–1045.

- Hessian, P.A.; Edgeworth, J.; Hogg, N. MRP-8 and MRP-14, two abundant Ca(2+)-binding proteins of neutrophils and monocytes. J. Leukoc. Biol. 1993, 53, 197–204.

- Kerkhoff, C.; Klempt, M.; Sorg, C. Novel insights into structure and function of MRP8 (S100A8) and MRP14 (S100A9). Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1998, 1448, 200–211.

- Schelbergen, R.F.; Blom, A.B.; van den Bosch, M.H.; Sloetjes, A.; Abdollahi-Roodsaz, S.; Schreurs, B.W.; Mort, J.S.; Vogl, T.; Roth, J.; van den Berg, W.B.; et al. Alarmins S100A8 and S100A9 elicit a catabolic effect in human osteoarthritic chondrocytes that is dependent on Toll-like receptor 4. Arthritis Rheum. 2012, 64, 1477–1487.

- Lu, S.M.; Yu, C.J.; Liu, Y.H.; Dong, H.Q.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, S.S.; Hu, L.Q.; Zhang, F.; Qian, Y.N.; Gui, B. S100A8 contributes to postoperative cognitive dysfunction in mice undergoing tibial fracture surgery by activating the TLR4/MyD88 pathway. Brain Behav. Immun. 2015, 44, 221–234.

- Vogl, T.; Tenbrock, K.; Ludwig, S.; Leukert, N.; Ehrhardt, C.; van Zoelen, M.A.; Nacken, W.; Foell, D.; van der Poll, T.; Sorg, C.; et al. Mrp8 and Mrp14 are endogenous activators of Toll-like receptor 4, promoting lethal, endotoxin-induced shock. Nat. Med. 2007, 13, 1042–1049.

- Buchanan, M.M.; Hutchinson, M.; Watkins, L.R.; Yin, H. Toll-like receptor 4 in CNS pathologies. J. Neurochem. 2010, 114, 13–27.

- Barton, G.M.; Medzhitov, R. Toll-like receptor signaling pathways. Science 2003, 300, 1524–1525.

- Zheng, J.; Wang, J.; Liu, H.; Chen, F.; Wang, H.; Chen, S.; Xie, J.; Zheng, Z.; Li, Z. Alarmins S100A8/A9 promote intervertebral disc degeneration and inflammation-related pain in a rat model through toll-like receptor-4 and activation of the NF-kappaB signaling pathway. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2022, 30, 998–1011.

- Saribal, D.; Hocaoglu-Emre, F.S.; Erdogan, S.; Bahtiyar, N.; Caglar Okur, S.; Mert, M. Inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and TNF-alpha in patients with hip fracture. Osteoporos. Int. 2019, 30, 1025–1031.

- Hirsch, J.; Vacas, S.; Terrando, N.; Yuan, M.; Sands, L.P.; Kramer, J.; Bozic, K.; Maze, M.M.; Leung, J.M. Perioperative cerebrospinal fluid and plasma inflammatory markers after orthopedic surgery. J. Neuroinflam. 2016, 13, 211.

- Chen, A.Q.; Fang, Z.; Chen, X.L.; Yang, S.; Zhou, Y.F.; Mao, L.; Xia, Y.P.; Jin, H.J.; Li, Y.N.; You, M.F.; et al. Microglia-derived TNF-alpha mediates endothelial necroptosis aggravating blood brain-barrier disruption after ischemic stroke. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 487.

- Shan, B.; Pan, H.; Najafov, A.; Yuan, J. Necroptosis in development and diseases. Genes Dev. 2018, 32, 327–340.

- Takata, F.; Dohgu, S.; Matsumoto, J.; Takahashi, H.; Machida, T.; Wakigawa, T.; Harada, E.; Miyaji, H.; Koga, M.; Nishioku, T.; et al. Brain pericytes among cells constituting the blood-brain barrier are highly sensitive to tumor necrosis factor-alpha, releasing matrix metalloproteinase-9 and migrating in vitro. J. Neuroinflam. 2011, 8, 106.

- Dillon, S.T.; Otu, H.H.; Ngo, L.H.; Fong, T.G.; Vasunilashorn, S.M.; Xie, Z.; Kunze, L.J.; Vlassakov, K.V.; Abdeen, A.; Lange, J.K.; et al. Patterns and Persistence of Perioperative Plasma and Cerebrospinal Fluid Neuroinflammatory Protein Biomarkers After Elective Orthopedic Surgery Using SOMAscan. Anesth. Analg. 2022.

- Hu, J.; Feng, X.; Valdearcos, M.; Lutrin, D.; Uchida, Y.; Koliwad, S.K.; Maze, M. Interleukin-6 is both necessary and sufficient to produce perioperative neurocognitive disorder in mice. Br. J. Anaesth. 2018, 120, 537–545.

- Ruiz-Sauri, A.; Orduna-Valls, J.M.; Blasco-Serra, A.; Tornero-Tornero, C.; Cedeno, D.L.; Bejarano-Quisoboni, D.; Valverde-Navarro, A.A.; Benyamin, R.; Vallejo, R. Glia to neuron ratio in the posterior aspect of the human spinal cord at thoracic segments relevant to spinal cord stimulation. J. Anat. 2019, 235, 997–1006.

- Hanisch, U.K. Microglia as a source and target of cytokines. Glia 2002, 40, 140–155.

- Perry, V.H.; Nicoll, J.A.; Holmes, C. Microglia in neurodegenerative disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2010, 6, 193–201.

- Gautier, E.L.; Shay, T.; Miller, J.; Greter, M.; Jakubzick, C.; Ivanov, S.; Helft, J.; Chow, A.; Elpek, K.G.; Gordonov, S.; et al. Gene-expression profiles and transcriptional regulatory pathways that underlie the identity and diversity of mouse tissue macrophages. Nat. Immunol. 2012, 13, 1118–1128.

- Gordon, S.; Martinez, F.O. Alternative activation of macrophages: Mechanism and functions. Immunity 2010, 32, 593–604.

- Mackaness, G.B. Cellular immunity and the parasite. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1977, 93, 65–73.

- Boche, D.; Perry, V.H.; Nicoll, J.A. Review: Activation patterns of microglia and their identification in the human brain. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 2013, 39, 3–18.

- Minagar, A.; Shapshak, P.; Fujimura, R.; Ownby, R.; Heyes, M.; Eisdorfer, C. The role of macrophage/microglia and astrocytes in the pathogenesis of three neurologic disorders: HIV-associated dementia, Alzheimer disease, and multiple sclerosis. J. Neurol. Sci. 2002, 202, 13–23.

- Liddelow, S.A.; Guttenplan, K.A.; Clarke, L.E.; Bennett, F.C.; Bohlen, C.J.; Schirmer, L.; Bennett, M.L.; Munch, A.E.; Chung, W.S.; Peterson, T.C.; et al. Neurotoxic reactive astrocytes are induced by activated microglia. Nature 2017, 541, 481–487.

- Witcher, K.G.; Bray, C.E.; Chunchai, T.; Zhao, F.; O’Neil, S.M.; Gordillo, A.J.; Campbell, W.A.; McKim, D.B.; Liu, X.; Dziabis, J.E.; et al. Traumatic Brain Injury Causes Chronic Cortical Inflammation and Neuronal Dysfunction Mediated by Microglia. J. Neurosci. 2021, 41, 1597–1616.

- Rocha, S.M.; Cristovão, A.C.; Campos, F.L.; Fonseca, C.P.; Baltazar, G. Astrocyte-derived GDNF is a potent inhibitor of microglial activation. Neurobiol. Dis. 2012, 47, 407–415.

- Liu, J.; Shen, Q.; Zhang, H.; Xiao, X.; Lv, C.; Chu, Y.; Shen, Y.; Wang, D.; Shen, Q. The Potential Protective Effect of Mesencephalic Astrocyte-Derived Neurotrophic Factor on Post-Operative Delirium via Inhibiting Inflammation and Microglia Activation. J. Inflamm. Res. 2021, 14, 2781–2791.

- Pizzino, G.; Irrera, N.; Cucinotta, M.; Pallio, G.; Mannino, F.; Arcoraci, V.; Squadrito, F.; Altavilla, D.; Bitto, A. Oxidative Stress: Harms and Benefits for Human Health. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 8416763.

- Reis, P.A.; Castro-Faria-Neto, H.C. Systemic Response to Infection Induces Long-Term Cognitive Decline: Neuroinflammation and Oxidative Stress as Therapeutical Targets. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 742158.

- Anasooya Shaji, C.; Robinson, B.D.; Yeager, A.; Beeram, M.R.; Davis, M.L.; Isbell, C.L.; Huang, J.H.; Tharakan, B. The Tri-phasic Role of Hydrogen Peroxide in Blood-Brain Barrier Endothelial cells. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 133.

- Schreibelt, G.; Kooij, G.; Reijerkerk, A.; van Doorn, R.; Gringhuis, S.I.; van der Pol, S.; Weksler, B.B.; Romero, I.A.; Couraud, P.O.; Piontek, J.; et al. Reactive oxygen species alter brain endothelial tight junction dynamics via RhoA, PI3 kinase, and PKB signaling. FASEB J. 2007, 21, 3666–3676.

- Lochhead, J.J.; McCaffrey, G.; Quigley, C.E.; Finch, J.; DeMarco, K.M.; Nametz, N.; Davis, T.P. Oxidative stress increases blood-brain barrier permeability and induces alterations in occludin during hypoxia-reoxygenation. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2010, 30, 1625–1636.

- Lischper, M.; Beuck, S.; Thanabalasundaram, G.; Pieper, C.; Galla, H.J. Metalloproteinase mediated occludin cleavage in the cerebral microcapillary endothelium under pathological conditions. Brain Res. 2010, 1326, 114–127.

- Wu, M.Y.; Gao, F.; Yang, X.M.; Qin, X.; Chen, G.Z.; Li, D.; Dang, B.Q.; Chen, G. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 regulates the blood brain barrier via the hedgehog pathway in a rat model of traumatic brain injury. Brain Res. 2020, 1727, 146553.

- Lopez, M.G.; Hughes, C.G.; DeMatteo, A.; O’Neal, J.B.; McNeil, J.B.; Shotwell, M.S.; Morse, J.; Petracek, M.R.; Shah, A.S.; Brown, N.J.; et al. Intraoperative Oxidative Damage and Delirium after Cardiac Surgery. Anesthesiology 2020, 132, 551–561.

- Petronilli, V.; Costantini, P.; Scorrano, L.; Colonna, R.; Passamonti, S.; Bernardi, P. The voltage sensor of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore is tuned by the oxidation-reduction state of vicinal thiols. Increase of the gating potential by oxidants and its reversal by reducing agents. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 16638–16642.

- Gouriou, Y.; Demaurex, N.; Bijlenga, P.; De Marchi, U. Mitochondrial calcium handling during ischemia-induced cell death in neurons. Biochimie 2011, 93, 2060–2067.

- Zhang, Y.; Dong, Y.; Xu, Z.; Xie, Z. Propofol and magnesium attenuate isoflurane-induced caspase-3 activation via inhibiting mitochondrial permeability transition pore. Med. Gas Res. 2012, 2, 20.

- Peng, M.; Zhang, C.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Nakazawa, H.; Kaneki, M.; Zheng, H.; Shen, Y.; Marcantonio, E.R.; Xie, Z. Battery of behavioral tests in mice to study postoperative delirium. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 29874.

- Zhang, J.; Gao, J.; Guo, G.; Li, S.; Zhan, G.; Xie, Z.; Yang, C.; Luo, A. Anesthesia and surgery induce delirium-like behavior in susceptible mice: The role of oxidative stress. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2018, 10, 2435–2444.

- Prolo, C.; Alvarez, M.N.; Radi, R. Peroxynitrite, a potent macrophage-derived oxidizing cytotoxin to combat invading pathogens. Biofactors 2014, 40, 215–225.

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Li, J.; Jimenez, D.A.; Levitan, E.S.; Aizenman, E.; Rosenberg, P.A. Peroxynitrite-induced neuronal apoptosis is mediated by intracellular zinc release and 12-lipoxygenase activation. J. Neurosci. 2004, 24, 10616–10627.

More

Information

Subjects:

Clinical Neurology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.1K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

01 Nov 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No