| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sirius Huang | -- | 1161 | 2022-10-28 01:41:41 |

Video Upload Options

A g-factor (also called g value or dimensionless magnetic moment) is a dimensionless quantity that characterizes the magnetic moment and angular momentum of an atom, a particle or the nucleus. It is essentially a proportionality constant that relates the different observed magnetic moments μ of a particle to their angular momentum quantum numbers and a unit of magnetic moment (to make it dimensionless), usually the Bohr magneton or nuclear magneton.

1. Definition

1.1. Dirac Particle

The spin magnetic moment of a charged, spin-1/2 particle that does not possess any internal structure (a Dirac particle) is given by[1] [math]\displaystyle{ \boldsymbol \mu = g {e \over 2m} \mathbf S , }[/math] where μ is the spin magnetic moment of the particle, g is the g-factor of the particle, e is the elementary charge, m is the mass of the particle, and S is the spin angular momentum of the particle (with magnitude ħ/2 for Dirac particles).

1.2. Baryon or Nucleus

Protons, neutrons, nuclei and other composite baryonic particles have magnetic moments arising from their spin (both the spin and magnetic moment may be zero, in which case the g-factor is undefined). Conventionally, the associated g-factors are defined using the nuclear magneton, and thus implicitly using the proton's mass rather than the particle's mass as for a Dirac particle. The formula used under this convention is [math]\displaystyle{ \boldsymbol{\mu} = g {\mu_\text{N} \over \hbar} {\mathbf{I}} = g {e \over 2 m_\text{p}} \mathbf{I} , }[/math] where μ is the magnetic moment of the nucleon or nucleus resulting from its spin, g is the effective g-factor, I is its spin angular momentum, μN is the nuclear magneton, e is the elementary charge and mp is the proton rest mass.

2. Calculation

2.1. Electron g-Factors

There are three magnetic moments associated with an electron: one from its spin angular momentum, one from its orbital angular momentum, and one from its total angular momentum (the quantum-mechanical sum of those two components). Corresponding to these three moments are three different g-factors:

Electron spin g-factor

The most known of these is the electron spin g-factor (more often called simply the electron g-factor), ge, defined by

- [math]\displaystyle{ \boldsymbol{\mu}_{\text{s}} = g_\text{e} {\mu_\text{B} \over \hbar} \mathbf{S} }[/math]

where μs is the magnetic moment resulting from the spin of an electron, S is its spin angular momentum, and [math]\displaystyle{ \mu_\text{B}=e\hbar/2m_\text{e} }[/math] is the Bohr magneton. In atomic physics, the electron spin g-factor is often defined as the absolute value or negative of ge:

- [math]\displaystyle{ g_\text{s} = |g_\text{e}| = -g_\text{e} . }[/math]

The z-component of the magnetic moment then becomes

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mu_\text{z} =-g_\text{s} \mu_\text{B} m_\text{s} }[/math]

The value gs is roughly equal to 2.002318, and is known to extraordinary precision.[2][3] The reason it is not precisely two is explained by quantum electrodynamics calculation of the anomalous magnetic dipole moment.[4] The spin g-factor is related to spin frequency for a free electron in a magnetic field of a cyclotron:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \nu_\text{s} = \frac{g}{2} \nu_\text{c} }[/math]

Electron orbital g-factor

Secondly, the electron orbital g-factor, gL, is defined by

- [math]\displaystyle{ \boldsymbol{\mu}_L = -g_L {\mu_\mathrm{B} \over \hbar} \mathbf{L} , }[/math]

where μL is the magnetic moment resulting from the orbital angular momentum of an electron, L is its orbital angular momentum, and μB is the Bohr magneton. For an infinite-mass nucleus, the value of gL is exactly equal to one, by a quantum-mechanical argument analogous to the derivation of the classical magnetogyric ratio. For an electron in an orbital with a magnetic quantum number ml, the z-component of the orbital angular momentum is

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mu_\text{z} = -g_L \mu_\text{B} m_\text{l} }[/math]

which, since gL = 1, is −μBml

For a finite-mass nucleus, there is an effective g value[5]

- [math]\displaystyle{ g_L=1-\frac{1}{M} }[/math]

where M is the ratio of the nuclear mass to the electron mass.

Total angular momentum (Landé) g-factor

Thirdly, the Landé g-factor, gJ, is defined by

- [math]\displaystyle{ |\boldsymbol{\mu_\text{J}}|= g_J {\mu_\text{B} \over \hbar} |\mathbf{J}| }[/math]

where μJ is the total magnetic moment resulting from both spin and orbital angular momentum of an electron, J = L + S is its total angular momentum, and μB is the Bohr magneton. The value of gJ is related to gL and gs by a quantum-mechanical argument; see the article Landé g-factor. μJ and J vectors are not colinear, so only their magnitudes can be compared.

2.2. Muon g-Factor

The muon, like the electron, has a g-factor associated with its spin, given by the equation

- [math]\displaystyle{ \boldsymbol \mu = g {e \over 2m_\mu} \mathbf{S} , }[/math]

where μ is the magnetic moment resulting from the muon's spin, S is the spin angular momentum, and mμ is the muon mass.

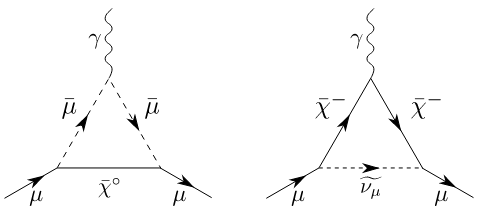

That the muon g-factor is not quite the same as the electron g-factor is mostly explained by quantum electrodynamics and its calculation of the anomalous magnetic dipole moment. Almost all of the small difference between the two values (99.96% of it) is due to a well-understood lack of heavy-particle diagrams contributing to the probability for emission of a photon representing the magnetic dipole field, which are present for muons, but not electrons, in QED theory. These are entirely a result of the mass difference between the particles.

However, not all of the difference between the g-factors for electrons and muons is exactly explained by the Standard Model. The muon g-factor can, in theory, be affected by physics beyond the Standard Model, so it has been measured very precisely, in particular at the Brookhaven National Laboratory. In the E821 collaboration final report in November 2006, the experimental measured value is 2.0023318416(13), compared to the theoretical prediction of 2.00233183620(86).[6] This is a difference of 3.4 standard deviations, suggesting that beyond-the-Standard-Model physics may be having an effect. The Brookhaven muon storage ring was transported to Fermilab where the Muon g–2 experiment used it to make more precise measurements of muon g-factor. On April 7, 2021, the Fermilab Muon g−2 collaboration presented and published a new measurement of the muon magnetic anomaly.[7] When the Brookhaven and Fermilab measurements are combined, the new world average differs from the theory prediction by 4.2 standard deviations.

3. Measured g-Factor Values

| Particle | Symbol | g-factor | Relative standard uncertainty |

|---|---|---|---|

| electron | ge | −2.00231930436256(35) | 1.7×10−13[8] |

| muon – (experiment-Brookhaven-2006) | gμ | −2.0023318418(13) | 6.3×10−10[9] |

| muon – (experiment-Fermilab-2021) | gμ | −2.002 331 8408(11) | 5.4 × 10−10 |

| muon – (experiment-world-average-2021) | gμ | −2.002 331 84121(82) | 4.1 × 10−10 |

| muon – (theory-June2020) | gμ | −2.002 331 83620(86) | 4.3 × 10−10 |

| neutron | gn | −3.82608545(90) | 2.4×10−7[10] |

| proton | gp | +5.5856946893(16) | 2.9×10−10[11] |

The electron g-factor is one of the most precisely measured values in physics.

References

- Povh, Bogdan; Rith, Klaus; Scholz, Christoph; Zetsche, Frank (2013-04-17). Particles and Nuclei. ISBN 978-3-662-05023-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=HC_qCAAAQBAJ&pg=PA74.

- Gabrielse, Gerald; Hanneke, David (October 2006). "Precision pins down the electron's magnetism". CERN Courier 46 (8): 35–37. http://cerncourier.com/main/article/46/8/20. Retrieved 2007-05-27.

- Odom, B.; Hanneke, D.; d’Urso, B.; Gabrielse, G. (2006). "New measurement of the electron magnetic moment using a one-electron quantum cyclotron". Physical Review Letters 97 (3): 030801. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.97.030801. PMID 16907490. Bibcode: 2006PhRvL..97c0801O. https://dx.doi.org/10.1103%2FPhysRevLett.97.030801

- Brodsky, S; Franke, V; Hiller, J; McCartor, G; Paston, S; Prokhvatilov, E (2004). "A nonperturbative calculation of the electron's magnetic moment". Nuclear Physics B 703 (1–2): 333–362. doi:10.1016/j.nuclphysb.2004.10.027. Bibcode: 2004NuPhB.703..333B. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.nuclphysb.2004.10.027

- Lamb, Willis E. (1952-01-15). "Fine Structure of the Hydrogen Atom. III". Physical Review 85 (2): 259–276. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.85.259. PMID 17775407. Bibcode: 1952PhRv...85..259L. https://dx.doi.org/10.1103%2FPhysRev.85.259

- Hagiwara, K.; Martin, A. D.; Nomura, Daisuke; Teubner, T. (2007). "Improved predictions for g−2 of the muon and αQED(M2Z)". Physics Letters B 649 (2–3): 173–179. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2007.04.012. Bibcode: 2007PhLB..649..173H. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.physletb.2007.04.012

- B. Abi (7 April 2021). "Measurement of the Positive Muon Anomalous Magnetic Moment to 0.46 ppm". Physical Review Letters 126 (14): 141801. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.126.141801. ISSN 0031-9007. PMID 33891447. https://dx.doi.org/10.1103%2FPhysRevLett.126.141801

- "2018 CODATA Value: electron g factor". The NIST Reference on Constants, Units, and Uncertainty. NIST. 20 May 2019. http://physics.nist.gov/cgi-bin/cuu/Value?gem. Retrieved 2019-05-20.

- "2018 CODATA Value: muon g factor". The NIST Reference on Constants, Units, and Uncertainty. NIST. 20 May 2019. http://physics.nist.gov/cgi-bin/cuu/Value?gmum. Retrieved 2019-05-20.

- "CODATA Value: neutron g factor". NIST. https://physics.nist.gov/cgi-bin/cuu/Value?gnn#mid.

- "2018 CODATA Value: proton g factor". The NIST Reference on Constants, Units, and Uncertainty. NIST. June 2015. http://physics.nist.gov/cgi-bin/cuu/Value?gp. Retrieved 2019-03-08.

- "CODATA values of the fundamental constants". NIST. http://physics.nist.gov/cgi-bin/cuu/Category?view=html&All+values.x=80&All+values.y=11.