Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sabrin R. M. Ibrahim | -- | 4914 | 2022-10-27 10:07:45 | | | |

| 2 | Jessie Wu | Meta information modification | 4914 | 2022-10-28 02:44:23 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Ibrahim, S.R.M.; Omar, A.M.; Muhammad, Y.A.; Alqarni, A.A.; Alshehri, A.M.; Mohamed, S.G.A.; Abdallah, H.M.; Elfaky, M.A.; Mohamed, G.A.; Xiao, J. Bioactivities of Phenalenones. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/31575 (accessed on 13 March 2026).

Ibrahim SRM, Omar AM, Muhammad YA, Alqarni AA, Alshehri AM, Mohamed SGA, et al. Bioactivities of Phenalenones. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/31575. Accessed March 13, 2026.

Ibrahim, Sabrin R. M., Abdelsattar M. Omar, Yosra A. Muhammad, Ali A. Alqarni, Abdullah M. Alshehri, Shaimaa G. A. Mohamed, Hossam M. Abdallah, Mahmoud A. Elfaky, Gamal A. Mohamed, Jianbo Xiao. "Bioactivities of Phenalenones" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/31575 (accessed March 13, 2026).

Ibrahim, S.R.M., Omar, A.M., Muhammad, Y.A., Alqarni, A.A., Alshehri, A.M., Mohamed, S.G.A., Abdallah, H.M., Elfaky, M.A., Mohamed, G.A., & Xiao, J. (2022, October 27). Bioactivities of Phenalenones. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/31575

Ibrahim, Sabrin R. M., et al. "Bioactivities of Phenalenones." Encyclopedia. Web. 27 October, 2022.

Copy Citation

Phenaloenones are structurally unique aromatic polyketides that have been reported in both microbial and plant sources. They possess a hydroxy perinaphthenone three-fused-ring system and exhibit diverse bioactivities, such as cytotoxic, antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anti-HIV properties, and tyrosinase, α-glucosidase, lipase, AchE (acetylcholinesterase), indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1, angiotensin-I-converting enzyme, and tyrosine phosphatase inhibition. They have a rich nucleophilic nucleus that has inspired many chemists and biologists to synthesize more of these related derivatives.

phenalenones

fungi

bioactivities

1. Introduction

In the last few decades, fungi have attracted tremendous scientific attention due to their capability to biosynthesize diverse classes of bio-metabolites, with varied bioactivities that are utilized for pharmaceutical, medicinal, and agricultural applications [1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14]. Obviously, the number of reported biometabolites from a fungal origin is rapidly growing [15][16][17][18][19]. Fungi can produce a wide variety of structurally unique polyketide-derived metabolites; among them are phenalenones, in which various post-modifications, including prenylation, transamination, rearrangement, and oxidation diversify their structures [20][21][22]. Phenalenones belong to the aromatic ketones, consisting of a hydroxyl-perinaphthenone three-fused-ring system that has been reported as from both microbial and plant sources [21]. They are recognized as the higher plants’ phytoalexins, which confer resistance toward pathogens [23][24]. Phenalenones are also known as pollutants, resulting from the combustion of fossil fuels [21]. The first report of the isolation of a phenalenone derivative from a fungal source was in 1955 [25][26]. Fungal phenalenones have immense structural diversity, such as hetero- and homo-dimerization, and high degrees of nitrogenation and oxygenation, as well as the capacity to be complexed with metals, incorporating additional carbon frameworks or an isoprene unit by the formation of either a linear ether or a trimethyl-hydrofuran moiety [20][21]. Moreover, many acetone adducts of phenalenones were also reported that have an extended carbon chain at ring A, such as the acyclic diterpenoid adducts. These fungal metabolites have been demonstrated to exhibit a wide range of bioactivities, such as cytotoxic, antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anti-HIV, and tyrosinase, α-glucosidase, lipase, AchE (acetylcholinesterase), indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1, angiotensin-I-converting enzyme, and tyrosine phosphatase inhibition. They are of great interest as potential lead compounds for synthetic organic chemistry because of the stability of their anions, phenalenyl radicals, and cations, as well as their interesting photophysical properties [27][28][29].

2. Biological Activities of Phenalenones

The bioactivities of some of the reported metabolites have been investigated. In this regard, 70 metabolites have been associated with some type of biological action, including cytotoxic, antimalarial, antimycobacterial, anti-inflammatory, anti-angiogenic, immunosuppressive, and antioxidant properties, as well as IDO1, α-glucosidase (AG), ACE, tyrosinase, and PTP inhibition. This information has been discussed and listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Biological activities of the most active fungal phenalenones.

| Compound Name | Biological Activity | Assay, Organism, or Cell Line | Biological Results | Positive Control | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paecilomycone A (1) | Tyrosinase inhibition | Colorimetric-microtiter plates/Tyrosinase enzyme | 0.11 mM (IC50) | Kojic acid 0.10 mM (IC50) Arbutin 0.20 mM (IC50) |

[30] |

| Paecilomycone B (2) | Tyrosinase inhibition | Colorimetric-microtiter plates/Tyrosinase enzyme | 0.17 mM (IC50) | Kojic acid 0.10 mM (IC50) Arbutin 0.20 mM (IC50) |

[30] |

| Paecilomycone C (3) | Tyrosinase inhibition | Colorimetric-microtiter plates/Tyrosinase enzyme | 0.14 mM (IC50) | Kojic acid 0.10 mM (IC50) Arbutin 0.20 mM (IC50) |

[30] |

| Aspergillussanone A (5) | Cytotoxicity | Resazurin microplate/KB | 48.4 μM (IC50) | Ellipticine 4.1 μM (IC50) | [31] |

| Resazurin microplate/Vero | 34.2 μM (IC50) | Ellipticine 4.5 μM (IC50) | [31] | ||

| ent-Peniciherqueinone (8) | Adipogenesis induction | Adiponectin production assay/hBM-MSC(B7) | 57.5 µM (IC50) | Pioglitazone 0.69 µM (IC50) | [32] |

| Herqueinone (9) | Antioxidant | DPPH/DPPH• | 0.48 mM (IC50) | Butylated hydroxytoluene 0.11 mM (IC50) | [33] |

| Hydroxyl radical scavenging/OH• | 6.34 mM (IC50) | Tannic acid 0.26 mM (IC50) | [33] | ||

| Superoxide radical scavenging/O2•− | 4.11 mM (IC50) | Trolox 0.96 mM (IC50) | [33] | ||

| Isoherqueinone (12) | Adipogenesis induction | Adiponectin production assay/hBM-MSC(B7) | 39.7 µM (IC50) | Pioglitazone 0.69 µM (IC50) | [32] |

| Acetone adduct of a triketone (17) | Anti-inflammatory | Nitric oxide synthase/RAW 264.7 | 3.2 µM (IC50) | AMT 0.2 µM (IC50) | [32] |

| (+)-Sclerodin (21) | Cytotoxicity | SRB/U87MG | 55.99 µM (IC50) | Doxorubicin 1.2 µM (IC50) | [34] |

| SRB/C6 | 44.65 µM (IC50) | Doxorubicin 0.47 µM (IC50) | [34] | ||

| (−)-Sclerodinol (24) | Antimicrobial | Agar dilution/B. cereus | 25.0 µM (MIC) | Ciprofloxacin 0.39 µM (MIC) | [35] |

| Agar dilution/Proteus species | 50.0 µM (MIC) | Ciprofloxacin 0.78 µM (MIC) | [35] | ||

| Agar dilution/M. Phlei | 25.0 µM (MIC) | Ciprofloxacin 0.39 µM (MIC) | [35] | ||

| Agar dilution/B. subtilis | 12.5 µM (MIC) | Ciprofloxacin 0.39 µM (MIC) | [35] | ||

| Agar dilution/V. parahemolyticus | 12.5 µM (MIC) | Ciprofloxacin 0.39 µM (MIC) | [35] | ||

| Agar dilution/MRCNS | 50.0 µM (MIC) | Ciprofloxacin 25.0 µM (MIC) | [35] | ||

| Agar dilution/MRSA | 50.0 µM (MIC) | Ciprofloxacin > 50 µM (MIC) | [35] | ||

| Bipolarol C (26) | Antibacterial | REMA/B. cereus | 25.0 µg/mL (MIC) | Vancomycin 1.0 µg/mL (MIC) | [36] |

| 4-Hydroxysclerodin (27) | Anti-angiogenetic | Tube formation assay/HUVECs | 20.9 µM (IC50) | Sunitinib 1.5 µM (IC50) | [32] |

| (+)-Sclerodione (28) | Cytotoxicity | SRB/U87MG | 60.93 µM (IC50) | Doxorubicin 1.2 µM (IC50) | [34] |

| SRB/C6 | 60.81 µM (IC50) | Doxorubicin 0.47 µM (IC50) | [34] | ||

| Antibacterial | Micro-broth dilution/MRSA | 23.0 µg/mL (MIC) | Gentamicin 0.5 µg/mL (MIC) | [34] | |

| Micro-broth dilution/E. coli | 35.0 µg/mL (MIC) | Gentamicin 1.0 µg/mL (MIC) | [34] | ||

| (−)–Sclerodione (29) | α-Glucosidase inhibition | Colorimetric/α-Glucosidase | 120 µM (IC50) | N-deoxynojirimycin 130.5 µM (IC50) | [37] |

| Porcine-lipase inhibition | Colorimetric/Porcine lipase | 1.0 µM (IC50) | Orlistat 9.4 µM (IC50) | [37] | |

| (−)-Bipolaride B (30) | Antibacterial | REMA/B. cereus | 25.0 µg/mL (MIC) | Vancomycin 1.0 µg/mL (MIC) | [36] |

| Cytotoxicity | REMA/MCF-7 | 79.4 µM (IC50) | Doxorubicin 12.99 µM (IC50) Tamoxifen 19.39 µM (IC50) |

[36] | |

| REMA/KB | 96.8 µM (IC50) | Ellipticine 8.32 µM (IC50) Doxorubicin 1.15 µM (IC50) |

[36] | ||

| REMA/NCI-H187 | 56.5 µM (IC50) | Ellipticine 9.74 µM (IC50) Doxorubicin 0.19 µM (IC50) |

[36] | ||

| Peniciphenalenin H (31) | Antimicrobial | Agar dilution/Proteus species | 50.0 µM (MIC) | Ciprofloxacin 0.78 µM (MIC) | [35] |

| Agar dilution/B. subtilis | 25.0 µM (MIC) | Ciprofloxacin 0.39 µM (MIC) | [35] | ||

| Agar dilution/V. parahemolyticus | 25.0 µM (MIC) | Ciprofloxacin 0.39 µM (MIC) | [35] | ||

| Agar dilution/MRCNS | 25.0 µM (MIC) | Ciprofloxacin 25.0 µM (MIC) | [35] | ||

| Agar dilution/MRSA | 50.0 µM (MIC) | Ciprofloxacin > 50 µM (MIC) | [35] | ||

| Bipolarol A (32) | Cytotoxicity | REMA/MCF-7 | 110.4 µM (IC50) | Doxorubicin 12.99 µM (IC50) Tamoxifen 19.39 µM (IC50) |

[36] |

| (+)-Scleroderolide (33) | Cytotoxicity | SRB/U87MG | 37.26 µM (IC50) | Doxorubicin 1.2 µM (IC50) | [34] |

| SRB/C6 | 23.24 µM (IC50) | Doxorubicin 0.47 µM (IC50) | [34] | ||

| Antibacterial | Micro-broth dilution/MRSA | 7.0 µg/mL (MIC) | Gentamicin 0.5 µg/mL (MIC) | [34] | |

| Micro-broth dilution/E. coli | 9.0 µg/mL (MIC) | Gentamicin 1.0 µg/mL (MIC) | [34] | ||

| (−)–Scleroderolide (34) | α-Glucosidase inhibition | Colorimetric/α-Glucosidase | 48.7 µM (IC50) | N-Deoxynojirimycin 130.5 µM (IC50) | [37] |

| porcine-lipase inhibition | Colorimetric/Porcine lipase | 3.4 µM (IC50) | Orlistat 9.4 µM (IC50) | [37] | |

| (−)-Bipolaride A (36) | Antibacterial | REMA/B. cereus | 12.5 µg/mL (MIC) | Vancomycin 1.0 µg/mL (MIC) | [36] |

| Cytotoxicity | REMA/NCI-H187 | 60.2 µM (IC50) | Ellipticine 9.74 µM (IC50) Doxorubicin 0.19 µM (IC50) |

[36] | |

| (−)-Bipolaride E (39) | Antibacterial | REMA/B. cereus | 12.5 µg/mL (MIC) | Vancomycin 1.0 µg/mL (MIC) | [36] |

| Cytotoxicity | REMA/MCF-7 | 65.1 µM (IC50) | Doxorubicin 12.99 µM (IC50) Tamoxifen 19.39 µM (IC50) |

[36] | |

| REMA/KB | 94.4 µM (IC50) | Ellipticine 8.32 µM (IC50) Doxorubicin 1.15 µM (IC50) |

[36] | ||

| REMA/NCI-H187 | 86.9 µM (IC50) | Ellipticine 9.74 µM (IC50) Doxorubicin 0.19 µM (IC50) |

[36] | ||

| Bipolarol B (40) | Cytotoxicity | REMA/MCF-7 | 65.3 µM (IC50) | Doxorubicin 12.99 µM (IC50) Tamoxifen 19.39 µM (IC50) |

[36] |

| REMA/KB | 52.5 µM (IC50) | Ellipticine 8.32 µM (IC50) Doxorubicin 1.15 µM (IC50) |

[36] | ||

| REMA/NCI-H187 | 48.3 µM (IC50) | Ellipticine 9.74 µM (IC50) Doxorubicin 0.19 µM (IC50) |

[36] | ||

| Bipolarol D (41) | REMA/MCF-7 | REMA/MCF-7 | 108.7 µM (IC50) | Doxorubicin 12.99 µM (IC50) Tamoxifen 19.39 µM (IC50) |

[36] |

| (−)-Bipolaride C (42) | Antibacterial | REMA/B. cereus | 12.5 µg/mL (MIC) | Vancomycin 1.0 µg/mL (MIC) | [36] |

| Cytotoxicity | REMA/MCF-7 | 48.9 µM (IC50) | Doxorubicin 12.99 µM (IC50) Tamoxifen 19.39 µM (IC50) |

[36] | |

| REMA/KB | 34.4 µM (IC50) | Ellipticine 8.32 µM (IC50) Doxorubicin 1.15 µM (IC50) |

[36] | ||

| REMA/NCI-H187 | 59.8 µM (IC50) | Ellipticine 9.74 µM (IC50) Doxorubicin 0.19 µM (IC50) |

[36] | ||

| REMA/Vero | 53.1 µM (IC50) | Ellipticine 2.13 µM (IC50) | [36] | ||

| Flaviphenalenone A (45) | Cytotoxicity | MTT/A549 | 6.6 µg/mL (IC50) | Doxorubicin HCl 0.2 µg/mL (IC50) | [38] |

| MTT/MCF-7 | 10.0 µg/mL (IC50) | Doxorubicin HCl 0.4 µg/mL (IC50) | [38] | ||

| Flaviphenalenone B (46) | α-Glucosidase inhibition | Colorimetrically/α-Glucosidase | 94.95 µM (IC50) | Acarbose 685.36 µM (IC50) | [38] |

| Flaviphenalenone C (47) | α-Glucosidase inhibition | Colorimetrically/α-Glucosidase | 78.96 µM (IC50) | Acarbose 685.36 µM (IC50) | [38] |

| Cytotoxicity | MTT/A549 | 28.5 µg/mL (IC50) | Doxorubicin HCl 0.2 µg/mL (IC50) | [38] | |

| MTT/MCF-7 | 50.0 µg/mL (IC50) | Doxorubicin HCl 0.4 µg/mL (IC50) | [38] | ||

| Auxarthrone A (49) | Antifungal | Serial dilution/C. neoformans | 3.2 µg/mL (MIC) | Amphotericin B 0.8 µg/mL (MIC) | [39] |

| Serial dilution/C. albicans | 3.2 µg/mL (MIC) | Amphotericin B 0.8 µg/mL (MIC) | [39] | ||

| Auxarthrone B (50) | Antifungal | Serial dilution/C. neoformans | 12.8 µg/mL (MIC) | Amphotericin B 0.8 µg/mL (MIC) | [39] |

| Serial dilution/C. albicans | 25.6 µg/mL (MIC) | Amphotericin B 0.8 µg/mL (MIC) | [39] | ||

| Auxarthrone D (51) | Antifungal | Serial dilution/C. neoformans | 6.4 µg/mL (MIC) | Amphotericin B 0.8 µg/mL (MIC) | [39] |

| Serial dilution/C. albicans | 6.4 µg/mL (MIC) | Amphotericin B 0.8 µg/mL (MIC) | [39] | ||

| Auxarthrone C (52) | Antifungal | Serial dilution/C. neoformans | 25.6 µg/mL (MIC) | Amphotericin B 0.8 µg/mL (MIC) | [39] |

| Serial dilution/C. albicans | 51.2 µg/mL (MIC) | Amphotericin B 0.8 µg/mL (MIC) | [39] | ||

| FR-901235 (54) | Antifungal | Serial dilution/C. neoformans | 51.2 µg/mL (MIC) | Amphotericin B 0.8 µg/mL (MIC) | [39] |

| Serial dilution/C. albicans | 51.2 µg/mL (MIC) | Amphotericin B 0.8 µg/mL (MIC) | [39] | ||

| Aspergillussanone D (61) | Antibacterial | Broth microdilution/P. aeruginosa | 38.47 µg/mL (MIC50) | Streptomycin 0.34 µg/mL (MIC50) | [40] |

| Broth microdilution/S. aureus | 29.91 µg/mL (MIC50) | Penicillin 0.063 µg/mL (MIC50) | [40] | ||

| Aspergillussanone E (62) | Antibacterial | Broth microdilution/E. coli | 7.83 µg/mL (MIC50) | Streptomycin 0.34 µg/mL (MIC50) | [40] |

| Aspergillussanone F (63) | Antibacterial | Broth microdilution/P. aeruginosa | 26.56 µg/mL (MIC50) | Streptomycin 0.34 µg/mL (MIC50) | [40] |

| Broth microdilution/E. coli | 3.93 µg/mL (MIC50) | Streptomycin 0.25 µg/mL (MIC50) | [40] | ||

| Broth microdilution/S. aureus | 16.48 µg/mL (MIC50) | Penicillin 0.063 µg/mL (MIC50) | [40] | ||

| Aspergillussanone G (64) | Antibacterial | Broth microdilution/P. aeruginosa | 24.46 µg/mL (MIC50) | Streptomycin 0.34 µg/mL (MIC50) | [40] |

| Broth microdilution/S. aureus | 34.66 µg/mL (MIC50) | Penicillin 0.063 µg/mL (MIC50) | [40] | ||

| Aspergillussanone H (65) | Antibacterial | Broth microdilution/P. aeruginosa | 8.59 µg/mL (MIC50) | Streptomycin 0.34 µg/mL (MIC50) | [40] |

| Broth microdilution/E. coli | 5.87 µg/mL (MIC50) | Streptomycin 0.25 µg/mL (MIC50) | [40] | ||

| Aspergillussanone I (66) | Antibacterial | Broth microdilution/P. aeruginosa | 12.00 µg/mL (MIC50) | Streptomycin 0.34 µg/mL (MIC50) | [40] |

| Aspergillussanone J (67) | Antibacterial | Broth microdilution/P. aeruginosa | 28.50 µg/mL (MIC50) | Streptomycin 0.34 µg/mL (MIC50) | [40] |

| Broth microdilution/E. coli | 5.34 µg/mL (MIC50) | Streptomycin 0.25 µg/mL (MIC50) | [40] | ||

| Broth microdilution/S. aureus | 29.87 µg/mL (MIC50) | Penicillin 0.063 µg/mL (MIC50) | [40] | ||

| Aspergillussanone K (68) | Antibacterial | Broth microdilution/P. aeruginosa | 6.55 µg/mL (MIC50) | Streptomycin 0.34 µg/mL (MIC50) | [40] |

| Broth microdilution/S. aureus | 21.02 µg/mL (MIC50) | Penicillin 0.063 µg/mL (MIC50) | [40] | ||

| Aspergillussanone L (69) | Antibacterial | Broth microdilution/P. aeruginosa | 1.87 µg/mL (MIC50) | Streptomycin 0.34 µg/mL (MIC50) | [40] |

| Broth microdilution/S. aureus | 2.77 µg/mL (MIC50) | Penicillin 0.063 µg/mL (MIC50) | [40] | ||

| Broth microdilution/B. subtilis | 4.80 µg/mL (MIC50) | Penicillin 0.063 µg/mL (MIC50) | [40] | ||

| (S)-2-((S,2E,6E,10Z)-14,15-Dihydroxy-11-(hydroxymethyl)-3,7,15-trimethylhexadeca-2,6,10-trien-1-yl)-2,4,6,9-tetrahydroxy-5,7-dimethyl-1H-phenalene-1,3(2H)-dione (70) | Antibacterial | Broth microdilution/P. aeruginosa | 19.07 µg/mL (MIC50) | Streptomycin 0.34 µg/mL (MIC50) | [40] |

| Broth microdilution/E. coli | 1.88 µg/mL (MIC50) | Streptomycin 0.25 µg/mL (MIC50) | [40] | ||

| Asperphenalenone A (71) | Anti-HIV-1 | Luciferase assay/SupT1 cells | 4.2 µM (IC50) | Lamivudine 0.1 µM (IC50) Efavirenz 0.0004 µM (IC50) |

[41] |

| Asperphenalenone B (72) | Anti-HIV-1 | Luciferase assay/SupT1 cells | 32.6 µM (IC50) | Lamivudine 0.1 µM (IC50) Efavirenz 0.0004 µM (IC50) |

[41] |

| Asperphenalenone D (74) | Anti-HIV-1 | Luciferase assay/SupT1 cells | 2.4 µM (IC50) | Lamivudine 0.1 µM (IC50) Efavirenz 0.0004 µM (IC50) |

[41] |

| Anti-HIV-1 | Luciferase assay/SupT1 cells | 22.1 µM (IC50) | Lamivudine 0.1 µM (IC50) Efavirenz 0.0004 µM (IC50) |

[41] | |

| Peniciphenalenin G (83) | Antimicrobial | Agar dilution/B. cereus | 25.0 µM (MIC) | Ciprofloxacin 0.39 µM (MIC) | [35] |

| Agar dilution/Proteus species | 50.0 µM (MIC) | Ciprofloxacin 0.78 µM (MIC) | [35] | ||

| Agar dilution/M. Phlei | 50.0 µM (MIC) | Ciprofloxacin 0.39 µM (MIC) | [35] | ||

| Agar dilution/B. subtilis | 25.0 µM (MIC) | Ciprofloxacin 0.39 µM (MIC) | [35] | ||

| Agar dilution/V. Parahemolyticus | 50.0 µM (MIC) | Ciprofloxacin 0.39 µM (MIC) | [35] | ||

| Agar dilution/MRCNS | 25.0 µM (MIC) | Ciprofloxacin 25.0 µM (MIC) | [35] | ||

| Agar dilution/MRSA | 12.5 µM (MIC) | Ciprofloxacin > 50 µM (MIC) | [35] | ||

| Coniosclerodione (85) | Antimicrobial | Agar dilution/B. cereus | 25.0 µM (MIC) | Ciprofloxacin 0.39 µM (MIC) | [35] |

| Agar dilution/Proteus sp. | 25.0 µM (MIC) | Ciprofloxacin 0.78 µM (MIC) | [35] | ||

| Agar dilution/M. Phlei | 25.0 µM (MIC) | Ciprofloxacin 0.39 µM (MIC) | [35] | ||

| Agar dilution/B. subtilis | 12.5 µM (MIC) | Ciprofloxacin 0.39 µM (MIC) | [35] | ||

| Agar dilution/V. parahemolyticus | 12.5 µM (MIC) | Ciprofloxacin 0.39 µM (MIC) | [35] | ||

| Agar dilution/MRCNS | 12.5 µM (MIC) | Ciprofloxacin 25.0 µM (MIC) | [35] | ||

| Agar dilution/MRSA | 6.25 µM (MIC) | Ciprofloxacin > 50 µM (MIC) | [35] | ||

| Trypethelonamide A (86) | Cytotoxicity | CCK8/RKO | 63.6 µM (IC50) | Taxol 0.05 µM (IC50) | [42] |

| 5′-Hydroxytrypethelone (87) | Cytotoxicity | CCK8/RKO | 22.6 µM (IC50) | Taxol 0.05 µM (IC50) | [42] |

| (+)-8-Hydroxy-7-methoxytrypethelone (88) | Cytotoxicity | CCK8/RKO | 113.5 µM (IC50) | Taxol 0.05 µM (IC50) | [42] |

| CCK8/HepG2 | 183.2 µM (IC50) | Taxol 1.0 µM (IC50) | [42] | ||

| (+)-Trypethelone (89) | Cytotoxicity | CCK8/RKO | 49.3 µM (IC50) | Taxol 0.05 µM (IC50) | [42] |

| (−)-Trypethelone (90) | Cytotoxicity | CCK8/RKO | 30.3 µM (IC50) | Taxol 0.05 µM (IC50) | [42] |

| O-Desmethylfunalenone (100) | Antibacterial | REMA/B. subtilis | 265 µM (IC50) | Clotrimazole 0.4 µM (IC50) | [43] |

| Cytotoxicity | Resazurin microplate/NS-1 | 70 µM (IC50) | 5-Fluorouracil 4.6 µM (IC50) | [43] | |

| Funalenone (101) | hPTP1B1-400 inhibition | Photocolorimetric/hPTP1B1-400 | 6.1 µM (IC50) | Ursolic acid 4.3 µM (IC50) | [44] |

| Hispidulone B (103) | Cytotoxicity | MTT/A-549 | 2.71 µM (IC50) | cis-Platinum 8.73 µM (IC50) | [45] |

| MTT/Huh7 | 22.93 µM (IC50) | cis-Platinum 5.89 µM (IC50) | [45] | ||

| MTT/HeLa | 23.94 µM (IC50) | cis-Platinum 14.68 µM (IC50) | [45] | ||

| Aceneoherqueinone A (104) | Angiotensin-I-converting enzyme inhibition | Spectrophotometric/Hippuryl-L-histidyl-L-leucine | 3.10 µM (IC50) | Captopril 9.23 nM (IC50) | [46] |

| Aceneoherqueinone B (105) | Angiotensin-I-converting enzyme inhibition | Spectrophotometric/Hippuryl-L-histidyl-L-leucine | 11.28 µM (IC50) | Captopril 9.23 nM (IC50) | [46] |

| Erabulenol B (117) | Indoleamine dioxygenase 1 inhibition | ELISA/Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 | 13.69 µM (IC50) | Epacadostat 0.015 µM (IC50) | [47] |

| Erabulenol C (118) | Indoleamine dioxygenase 1 inhibition | ELISA/Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 | 14.38 µM (IC50) | Epacadostat 0.015 µM (IC50) | [47] |

| Duclauxin (120) | Antitumor | ELISA/EGFR | 0.95 µM (IC50) | Afatinib 0.0005 µM (IC50) | [48] |

| ELISA/CDC25B | 0.75 µM (IC50) | Na3VO4 0.52 µM (IC50) | [48] | ||

| Cytotoxicity | Resazurin microplate/NS-1 | 140 µM (IC50) | 5-Fluorouracil 4.6 µM (IC50) | [43] | |

| hPTP1B1-400 inhibition | Photocolorimetric/hPTP1B1-400 | 12.7 µM (IC50) | Ursolic acid 26.6 µM (IC50) | [49] | |

| Talaromycesone A (121) | Antibacterial | REMA/S. epidermidis | 3.70 µM (IC50) | Chloramphenicol 1.81 µM (IC50) | [50] |

| Antibacterial | REMA/MRSA | 5.48 µM (IC50) | Chloramphenicol 2.46 µM (IC50) | [50] | |

| AchE inhibition | Modified Ellman’s enzyme/Immunosorbent assay | 7.49 µM (IC50) | Huperzine 11.60 µM (IC50) | [50] | |

| Talaromycesone B (122) | Antibacterial | REMA/S. epidermidis | 17.36 µM (IC50) | Chloramphenicol 1.81 µM (IC50) | [50] |

| REMA/MRSA | 19.50 µM (IC50) | Chloramphenicol 2.46 µM (IC50) | [50] | ||

| hPTP1B1-400 inhibition | Photocolorimetric/hPTP1B1-400 | 82.1 µM (IC50) | Ursolic acid 26.6 µM (IC50) | [49] | |

| Bacillisporin A (123) | Antibacterial | Microtiter plate/S. aureus | 5.2 µg/mL (MIC) | Tetracycline 0.05 µg/mL (MIC) | [51] |

| Microtiter plate/S. hemolyticus | 9.5 µg/mL (MIC) | Tetracycline 29.2 µg/mL (MIC) | [51] | ||

| Microtiter plate/E. faecalis | 2.4 µg/mL (MIC) | Tetracycline 0.4 µg/mL (MIC) | [51] | ||

| 9a-Epi-bacillisporin E (124) | Antibacterial | Microtiter plate/S. aureus | 29.3 µg/mL (MIC) | Tetracycline 0.05 µg/mL (MIC) | [51] |

| Bacillisporin F (125) | Antibacterial | Microtiter plate/S. aureus | 15.6 µg/mL (MIC) | Tetracycline 0.05 µg/mL (MIC) | [51] |

| Antitumor | ELISA/EGFR | 4.41 µM (IC50) | Afatinib 0.0005 µM (IC50) | [48] | |

| ELISA/CDC25B | 0.40 µM (IC50) | Na3VO4 0.52 µM (IC50) | [48] | ||

| Antitumor | ELISA/EGFR | 4.41 µM (IC50) | Afatinib 0.0005 µM (IC50) | [48] | |

| ELISA/CDC25B | 0.40 µM (IC50) | Na3VO4 0.52 µM (IC50) | [48] | ||

| Bacillisporin G (127) | hPTP1B1-400 inhibition | Photocolorimetric/hPTP1B1-400 | 13.5 µM (IC50) | Ursolic acid 26.6 µM (IC50) | [49] |

| Bacillisporin H (128) | Cytotoxicity | MTT/HeLa | 49.5 µM (IC50) | Cisplatin 10.6 µM (IC50) | [51] |

| Antibacterial | Microtiter plate/S. aureus | 5.0 µg/mL (MIC) | Tetracycline 0.05 µg/mL (MIC) | [51] | |

| Microtiter plate/S. hemolyticus | 20.4 µg/mL (MIC) | Tetracycline 29.2 µg/mL (MIC) | [51] | ||

| Verruculosin A (129) | Antitumor | ELISA/EGFR | 0.92 µM (IC50) | Afatinib 0.0005 µM (IC50) | [48] |

| Antitumor | ELISA/CDC25B | 0.38 µM (IC50) | Na3VO4 0.52 µM (IC50) | [48] | |

| Verruculosin B (130) | Antitumor | ELISA/EGFR | 1.22 µM (IC50) | Afatinib 0.0005 µM (IC50) | [48] |

| Xenoclauxin (131) | Antitumor | ELISA/EGFR | 0.24 µM (IC50) | Afatinib 0.0005 µM (IC50) | [48] |

| ELISA/CDC25B | 0.26 µM (IC50) | Na3VO4 0.52 µM (IC50) | [48] | ||

| hPTP1B1-400 inhibition | Photocolorimetric/hPTP1B1-400 | 21.8 µM (IC50) | Ursolic acid 26.6 µM (IC50) | [49] |

Paecilomycones A–C (1–3) were purified from Paecilomyces gunnii culture extract with the aid of a preparatory HSCCC, guided by HPLC-HRESIMS, used as a tyrosinase inhibitor. Compound 1 was similar to myeloconone A2 (4), which was formerly separated from the lichen Myeloconis erumpens [52], except that 1 has an OH group at C-8 instead of an OCH3 group. Compound 3 was deduced as 9-amino-6,7,8-trihydroxy-3-methoxy-4-methyl-1H-phenalen-1-one; the existence of NH2 in 3 was confirmed by a positive purple reaction with a ninhydrin reagent in the TLC plate. They were characterized by means of spectroscopic analyses. These metabolites exhibited potent tyrosinase inhibitory potential (IC50s 0.11, 0.17, and 0.14 mM, respectively) in the form of kojic acid (IC50 0.10 mM), being stronger than arbutin (IC50 0.20 mM). This influence was found to be positively related to the number of OH groups [30] (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The structures of compounds 1–10.

Aspergillussanones A (5) and B (6) were separated from Aspergillus sp. PSU-RSPG185 broth extract. They differed from each other in the substitutions at C-8 and C-4, as well as in the C-4 configuration. The configuration of their double bonds was determined to be E, based on signal enhancement in the NOEDIFF experiment, and the 4S and 10′R in 5 and 4R and 10′R in 6 was assigned by the CD spectrum. Only compound 5 exhibited weak cytotoxic activity toward Vero cells and KB (IC50s 34.2 and 48.4 μM, respectively) in the resazurin microplate assay, compared to ellipticine (IC50 4.5 and 4.1 μM, respectively), whereas 6 was inactive against the tested cell lines. Additionally, they showed no antimalarial or antimycobacterial potential toward Plasmodium falciparum and Mycobacterium tuberculosis when using GFP (green fluorescent protein) and the micro-culture radioisotope technique, respectively [31] (Figure 1).

Eleven metabolites of the herqueinone subclass, including six new derivatives, ent-peniciherqueinone (8), 12-hydroxynorherqueinone (11), ent-isoherqueinone (13), oxopropylisoherqueinones A (15) and B (16), and 4-hydroxysclerodin (27) and the known analogs, 9, 12, 17, 22, and 34 were extracted from a marine-derived Penicillium sp. (Figure 2). The new metabolites’ configuration was assigned, based on specific rotations and chemical modifications. Compound 17 exhibited moderate anti-inflammatory activity (IC50 3.2 µM) towards mouse macrophage RAW 264.7 cells, compared to AMT (IC50 0.2 µM) in the nitric oxide synthase assay. In addition, 27 exhibited moderate anti-angiogenic potential (IC50 20.9 µM) toward HUVECs (human umbilical vascular endothelial cells), compared to sunitinib (IC50 1.5 µM), in the tube formation assay. Furthermore, 8 and 12 moderately induced adipogenesis (IC50 57.5 and 39.7 µM, respectively) in the hBM-MSCs (human bone marrow-mesenchymal stem cells), compared to pioglitazone (IC50 0.69 µM), in the adiponectin production assay [32].

Figure 2. The structures of compounds 11–22.

Lee et al. purified 18 from a culture of Penicillium herquei FT729, derived from Hawaiian volcanic soil by LC-MS-guided chemical analysis. It was identified by spectroscopic analysis, optical rotation, and LC-MS analysis. The pretreatment of T cells with 18 remarkably reduced IL-2 production and the expression of surface molecules, including CD-25 and -69, and activated T cell proliferation after TCR-mediated stimulation, as well as abrogating the NF-κB and MAPK pathways. Therefore, it effectively down-regulated T cell activity via the MAPK pathway, which indicated its immunosuppressive potential [53]. Furthermore, P. herquei PSURSPG93, obtained from soil, produced a new derivative, peniciherqueinone (7), along with the formerly separated derivatives: herqueinone (9), deoxyherqueinone (14), the acetone adduct of atrovenetinone (18) (as a mixture of epimers), sclerodin (20), and (−)-7,8-dihydro-3,6-dihydroxy-1,7,7,8-tetramethyl-5H-furo-[2′,3′,:5,6]naphtho[1,8-bc]furan-5-one (37). Compound 7 was structurally similar to 9, except for the disappearance of one olefinic proton signal. Its R-configuration at C-4 was determined by an anisotropic effect and CD spectroscopy, which was opposite to 9. Compounds 9, 14, and 20 had no cytotoxic effect toward MCF-7, KB, and noncancerous Vero cell lines. In addition, only 9 exhibited mild antioxidant potential, where it inhibited OH•, DPPH•, and O2•− (IC50 0.48, 6.34, and 4.11 mM, respectively) in the hydroxyl radical, DPPH, and superoxide radical scavenging assays, respectively, in comparison with tannic acid (OH•, IC50 0.26), butylated hydroxytoluene (DPPH•, IC50 0.11), and trolox (O2•−, IC50 0.96 mM) [33].

Intaraudom et al. purified the new derivatives, 25, 26, 30, 32, 36, and 39–42, together with 22 and 34, from the broth EtOAc extract of the marine-derived Lophiostoma bipolare BCC25910 (Figure 3). Their structures were assigned via spectroscopic analysis, whereas the C-2′, S-configuration was determined based on X-ray analysis, a chemical reaction, and a specific optical rotation negative sign. They showed no antimalarial activity toward the P. falciparum K-1 strain and no antifungal activity toward C. albicans. On the other hand, 25, 26, 36, 39, and 40 showed moderate antibacterial potential toward B. cereus (MICs 12.5 µg/mL). However, other compounds were inactive against B. cereus (concentration 25 µg/mL). Additionally, they exhibited weak cytotoxicity toward KB, MCF-7, NCI-H187, and Vero cells [36].

Figure 3. The structures of compounds 23–37.

Macabeo et al. purified 29, 34, and 90 from a culture of Pseudolophiostoma sp. MFLUCC-17-2081 obtained from a dried branch of Clematis fulvicoma. Compounds 29 and 34 conferred more potent α-glucosidase inhibition (IC50 48.7 and 120 µM, respectively) than N-deoxynojirimycin (IC50 130.5 µM). They also potently inhibited the hydrolysis of p-nitro-phenylbutyrate, using porcine lipase. Interestingly, 29 and 34 showed stronger inhibitory potential (IC50s 1.0 and 3.4 µM, respectively) than orlistat (IC50 9.4 µM). The in silico techniques employed revealed that 29 and 34 exhibited strong binding affinities to porcine pancreatic lipase and α-glucosidase through π–π and H-bonding interactions, while 90 was weakly active (IC50 > 100 µM) toward both enzymes [37].

Zhang et al. purified new derivatives, flaviphenalenones A–C (45–47), from solid cultures of Aspergillus flavipes PJ03-11 (Figure 4). The 6S absolute configuration of 45 was determined by the computational ECD method. Compound 47 was a positional isomer of 46. They represented the first report of phenalenones with a directly connected C-10 isoprene unit, whereas 47 had a keto-lactone group at C-8. Compounds 46 and 47 possessed potent α-glucosidase inhibitory potential (IC50s 94.95 and 78.96 µM, respectively) than acarbose (IC50 685.36 µM). On the other hand, 45 displayed significant cytotoxic capacities toward MCF-7 and A549 (IC50 10.0 and 6.6 µg/mL, respectively) compared to doxorubicin (IC50 0.4 and 0.2 µg/mL, respectively), while 47 showed moderate cytotoxicity toward A549 (IC50 28.5 µg/mL) [38].

Figure 4. The structures of compounds 38–47.

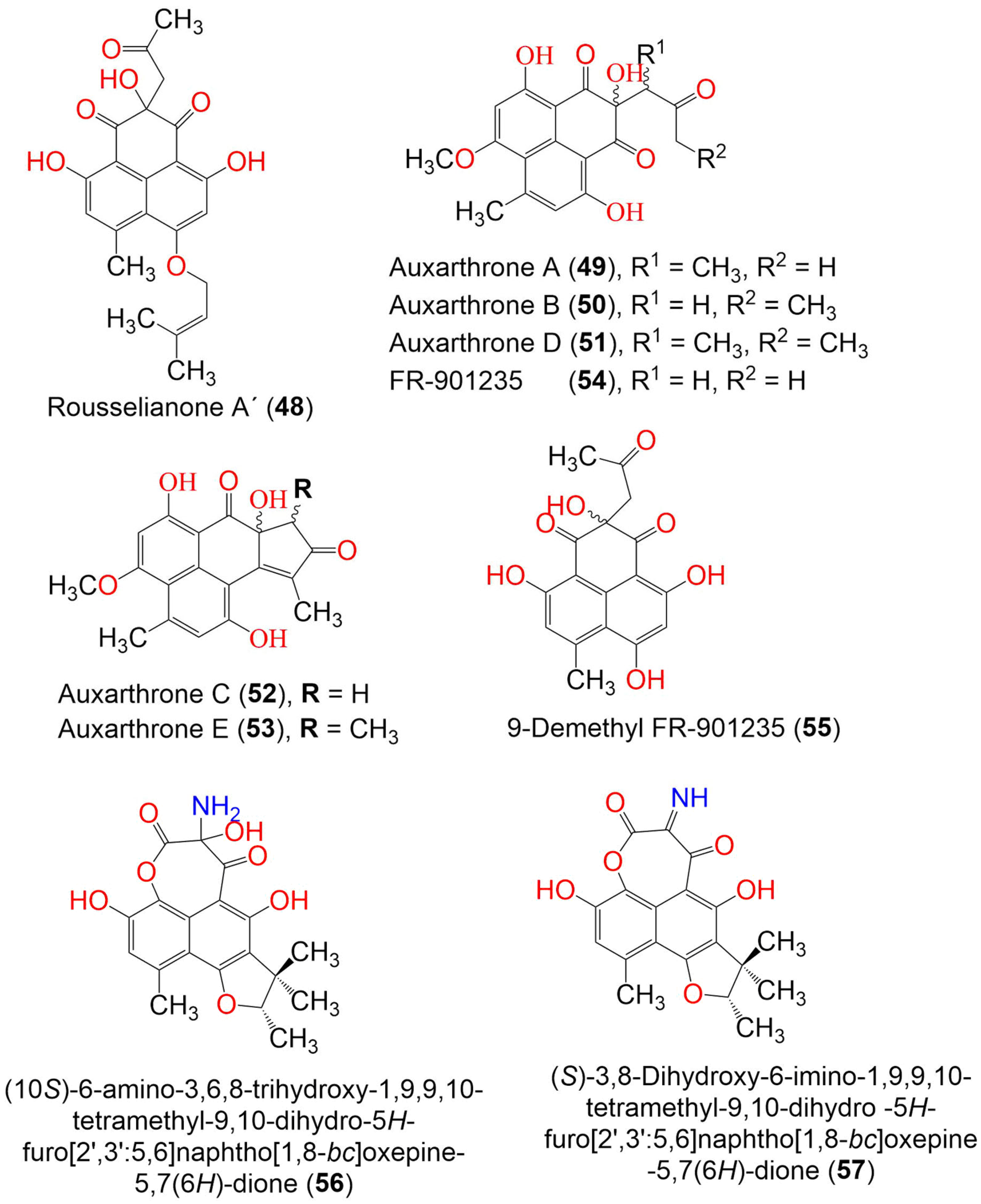

Auxarthrones A–E (49–53) and FR-901235 (54) were obtained from the culture of the coprophilous fungus Auxarthron pseudauxarthron TTI-0363 (Figure 5). Compounds 52 and 53 possessed an unusual 7a,8-dihydrocyclopenta[a]phenalene-7,9-dione ring system. Compound 49 was separated into a mixture of racemic diastereomers; their structures were confirmed by X-ray crystallography. Compounds 49 and 51 showed moderate antifungal potential toward C. albicans and C. neoformans (MICs 6.4 and 3.2 μg/mL, respectively), compared to amphotericin B (MIC 0.8 μg/mL). The other phenalenones were weakly active (MIC ranging from 6.4 to 51.2 μg/mL). On the other hand, they showed no significant cytotoxic effects against MDA-MB-451 and MDA-MB-231 [39].

Figure 5. The structures of compounds 48–57.

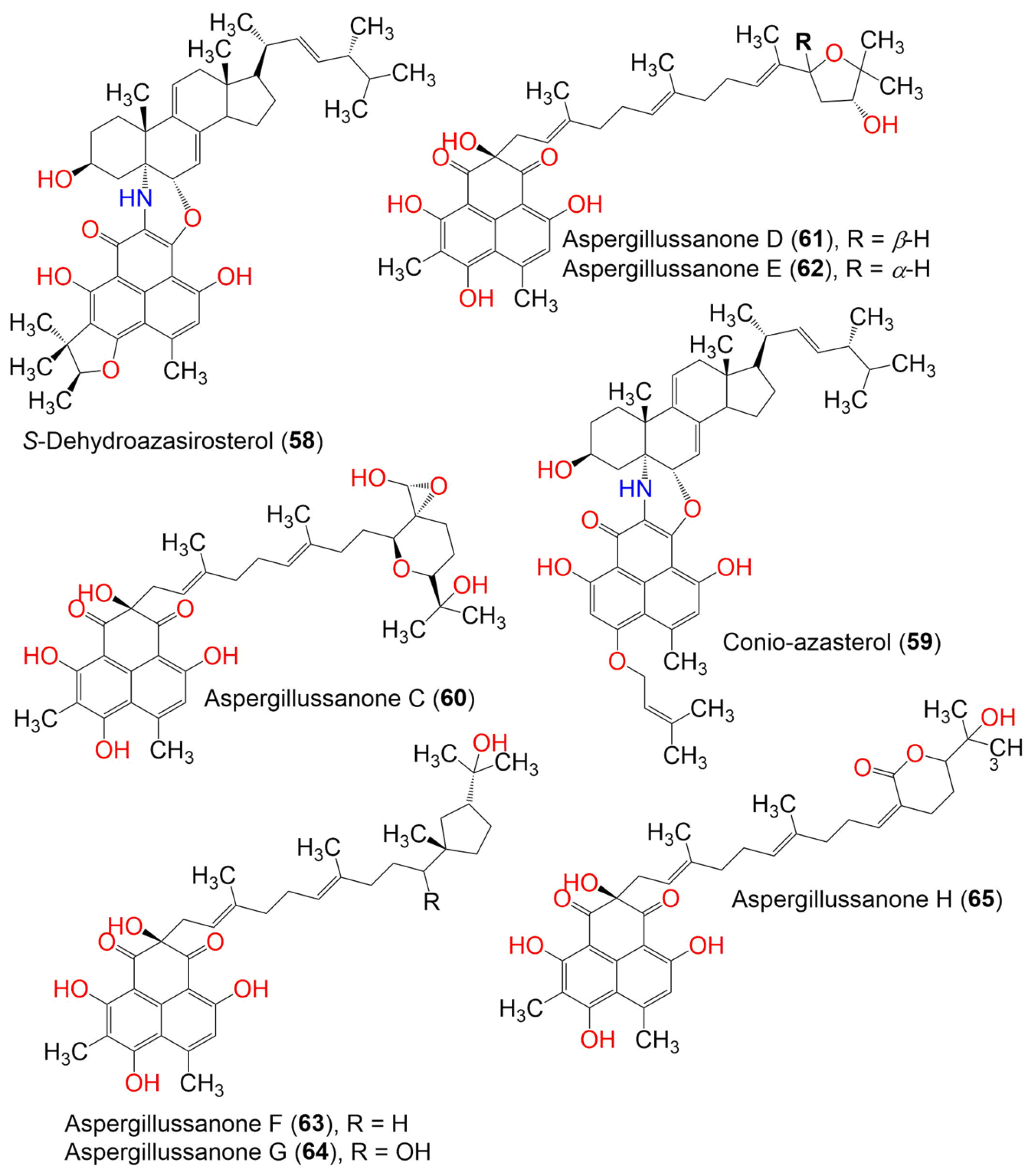

Compound 56 obtained from the marine-derived endophytic fungus, Coniothyrium cereale, harboring the Baltic Sea algae Enteromorpha sp., which had unprecedented imine functionality between two carbonyls to produce an oxepane-imine-dione ring. It exhibited a moderate cytotoxic potential toward the SKM1, U266, and K562 cancer cell lines (IC50s 75.0, 45.0, and 8.5 µM, respectively) in the MTT assay [54]. The new phenalenone derivatives, aspergillussanones C–L (60–69), along with the known analog 70, were isolated from the solid culture of Aspergillus sp. that was associated with Pinellia ternate (Figure 6 and Figure 7).

Figure 6. The structures of compounds 58–65.

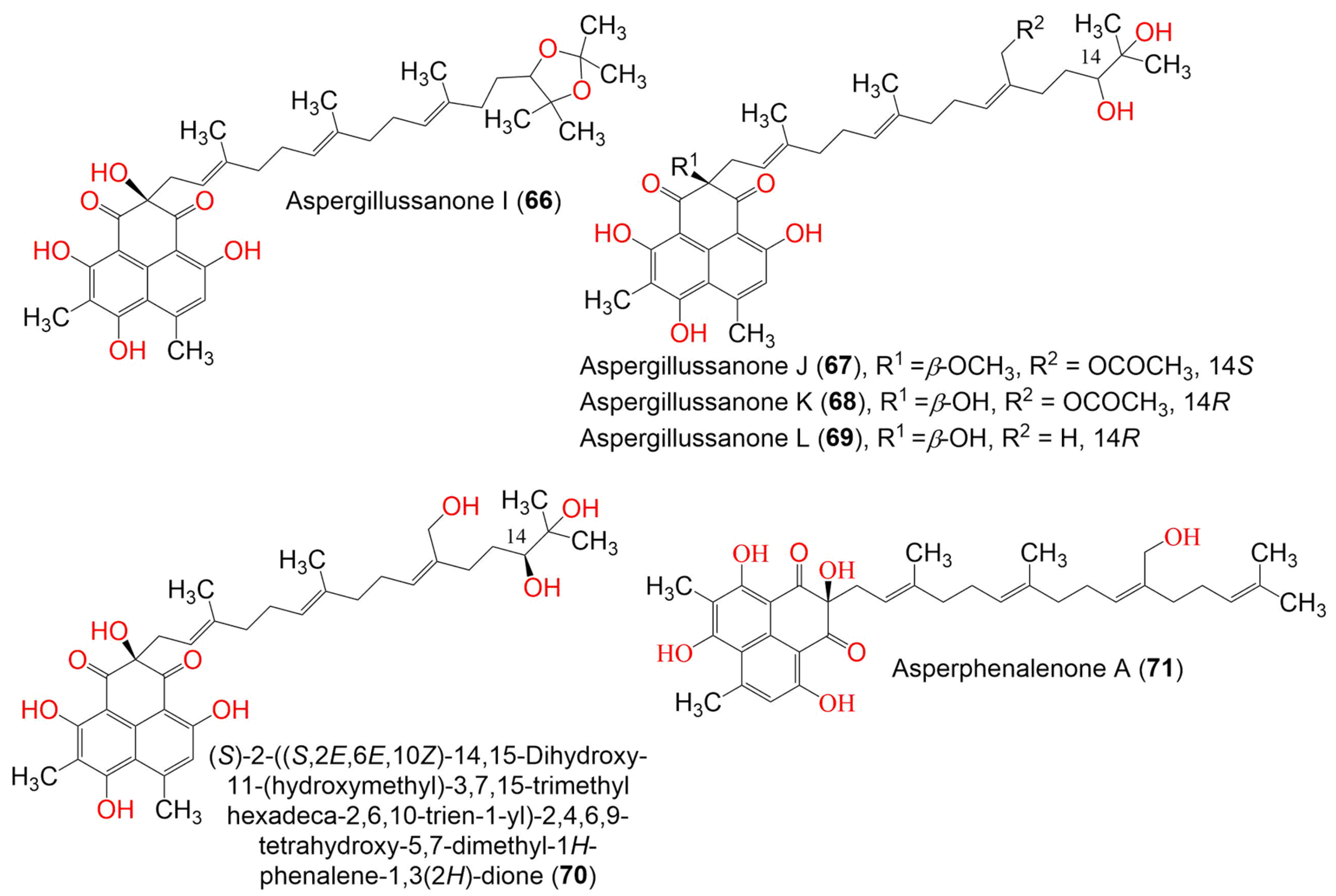

Figure 7. The structures of compounds 66–71.

Compounds 60–69 are unusual acyclic diterpenoid adducts that are partly epoxidized and variously oxidized to produce diverse heterocyclic analogs. Their structures and absolute configurations were established by spectroscopic, ECD, and Mo2(OCOCH3)4-induced ECD analyses. Their antibacterial effectiveness toward Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, and Bacillus subtilis was evaluated using the broth micro-dilution method. Compound 69 exhibited the most potent antibacterial potential against B. subtilis, S. aureus, and P. aeruginosa (MIC 4.80, 2.77, and 1.87 μg/mL, respectively), compared to streptomycin (MIC 0.34 μg/mL for P. aeruginosa) and penicillin (MIC 0.063 and 0.13 μg/mL for S. aureus and B. subtilis, respectively). Compounds 65–67 had potential versus P. aeruginosa (MIC50s 6.55–12.00 μg/mL). Meanwhile, 62, 63, 65, and 67 showed significant activity toward E. coli (MIC 3.93–7.83 μg/mL) [40].

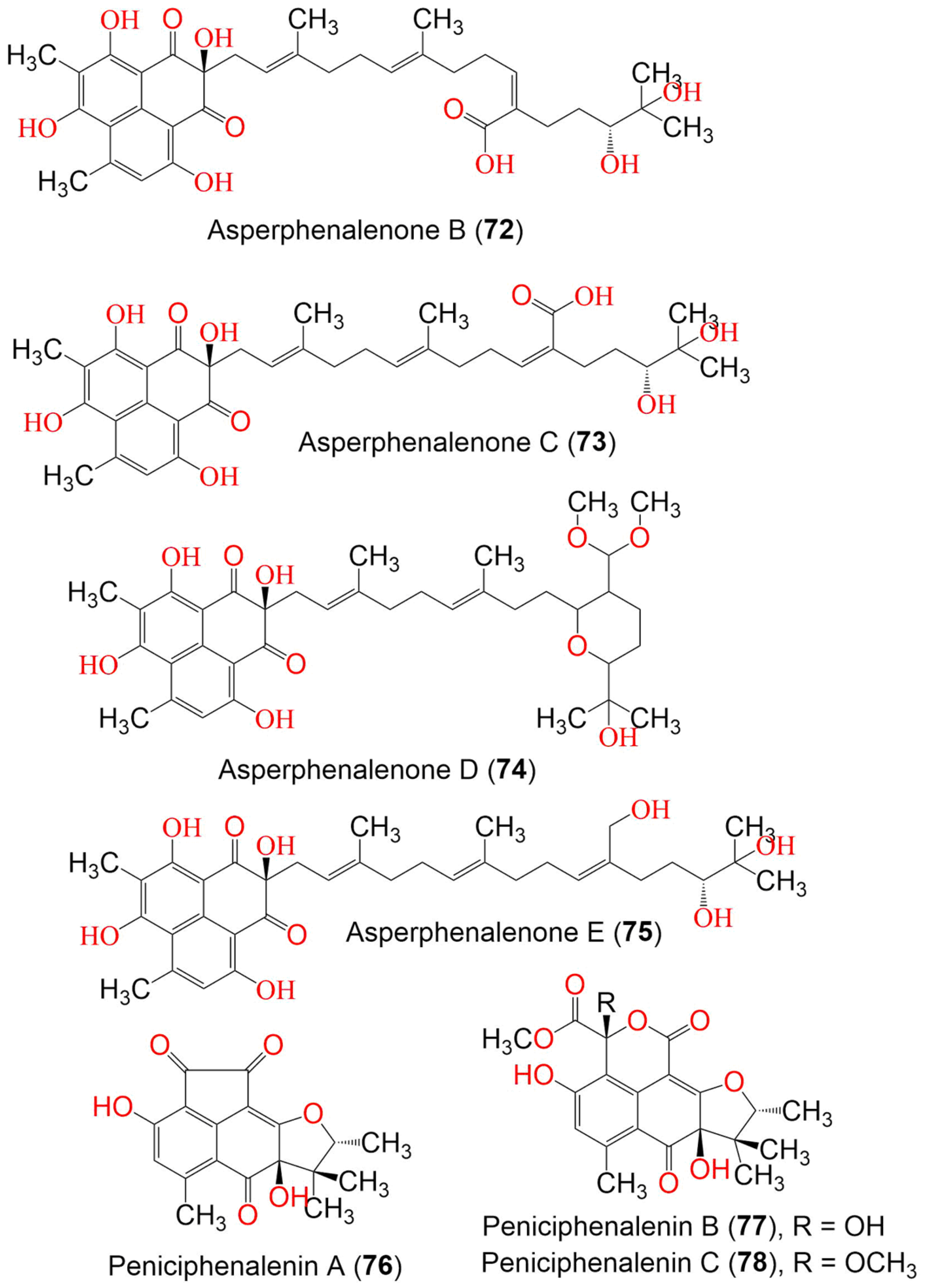

Aspergillus sp. CPCC 400735, which is associated with Kadsura longipedunculata, was found to biosynthesize the structurally unusual phenalenones, asperphenalenones A–E (71–75), these having a linear diterpene moiety that is connected to the phenalenone skeleton through a C-C bond (Figure 8). Their structures were established from extensive NMR spectroscopic analyses, while the absolute configuration was determined based on the CD spectra. Compounds 71 and 74 exhibited anti-HIV activity (IC50 4.5 and 2.4 µM, respectively), in comparison to lamivudine (IC50 0.1 µM) and efavirenz (IC50 0.0004 µM), using SupT1 cells in the luciferase assay system, while 72 and 75 exhibited weak activity (IC50 32.6 and 22.1 µM, respectively) [41].

Figure 8. The structures of compounds 72–78.

The new derivatives, peniciphenalenins A–F (76–81), along with the formerly reported 21, 28, and 33, were obtained from Penicillium sp. ZZ901 culture, using ODS and HPLC (Figure 9). Their structures were determined by extensive spectroscopic analysis, ECD calculation, optical rotation, and single X-ray diffraction. The analyses identified a phenalenone skeleton, fused to a trimethyl-furan ring. Compounds 28 and 33 showed antimicrobial activity toward MRSA and E. coli (MICs 23–35 µg/mL for 28 and 7.0–9.0 µg/mL for 33). On the other hand, 21, 28, and 33 showed weak antiproliferative activity against the glioma cells (IC50 23.24–6.93 µM), compared to doxorubicin (IC50 1.2 and 0.47 µM, respectively) [34].

Figure 9. The structures of compounds 73–86.

Han et al. separated three new red-colored phenalenone derivatives, peniciphenalenins G–I (83, 31, and 84), along with coniosclerodione (85) and (−) sclerodinol (24) from the marine sediment-derived fungus, Pleosporales sp. HDN1811400, using UV-HPLC guided investigation. Their absolute configurations were determined by detailed spectroscopic and ECD analyses, in addition to the chemical method. Compound 83 was the first example of a chlorinated phenalenone derivative. Compounds 24, 31, 83, and 85 showed antimicrobial potential versus B. cereus, Proteus sp., M. phlei, B. subtilis, V. parahemolyticus, E. tarda, MRCNS, and MRSA (MICs 6.25–50.0 µM). Compound 85 (MIC 6.25 µM) was more active than compound 84, indicating that 19-OH reduced the activity. Notably, compounds 24, 31, 83, and 85 showed better inhibitory potential toward MRCNS and MRSA than that of ciprofloxacin, indicating their potential regarding drug-resistant strains [35].

Basnet et al. reported the isolation of a new yellow compound, trypethelonamide A (86), and a new dark violet-red compound, 5′,-hydroxytrypethelone (87), along with a dark violet-red metabolites (+)-8-hydroxy-7-methoxytrypethelone (88), (+)-trypethelone (89), and (−)-trypethelone (90) from the cultured lichenized fungus Trypethelium eluteriae by using Sephadex LH-20, ODS, SiO2, and HPLC. They were fully characterized via spectroscopic and ECD spectral analyses (Figure 10). They showed moderate to weak cytotoxicity versus the RKO cell line (IC50 ranged from 22.6 to 113.5 µM), compared to taxol (IC50 0.05 µM) in the CCK8 assay, while they had no antioxidant potential in the DPPH assay (concentration 200 µM) [42].

Figure 10. The structures of compounds 87–102.

Two new metabolites, 8-methoxytrypethelone (93) and 5′-hydroxy-8-ethoxytrypethelone (95), along with compounds 20, 38, 89, 91, 92, and 94 were separated from mycobiont culture of Trypethelium eluteriae by preparative TLC and column chromatography. They were fully characterized by using spectroscopic, ECD, and X-ray analyses. Compound 89 (MIC 12.5 µg/mL) showed potent antimycobacterial potential toward M. tuberculosis, followed by 38 and 94 (MIC 50.0 µg/mL). Moreover, 89 had moderate potential (MIC 25.0 µg/mL) toward M. chitae, M. szulgai, M. phlei, M. flavescens, M. parafortuitum, and M. kansasii. In addition, compounds 89 and 94 were active versus S. aureus (MIC 25 µg/mL) [55]. Funalenone (101) was also purified as a PTP inhibitor from a marine-derived fungal strain of Aspergillus sp. SF-5929 and was tested for its inhibitory potential on hPTP1B1-400 in a photocolorimetric assay using the hPTP1B1 enzyme. It exhibited powerful PTP1B inhibitory potential (IC50 6.1 µM), compared to ursolic acid (IC50 4.3 µM). It was found that 101 was a noncompetitive PTP1B inhibitor that targeted the active or allosteric site of the enzyme [44]. Chaetosphaeronema hispidulum yielded two new phenalenones, hispidulones A (102) and B (103), which were assigned by spectroscopic and ECD analyses (Figure 11).

Figure 11. The structures of compounds 103–115.

Compound 102 had a cyclohexa-2,5-dien-1-one moiety, whereas 103 possessed a hemiacetal OCH3 group that was uncommon in phenalenone analogs. Compound 103 showed cytotoxic potential toward A-549, Huh7, and HeLa cells (IC50 2.71, 22.93, and 23.94 μM, respectively), compared with cis-platinum (IC50 8.73, 5.89, and 14.68 μM, respectively), whereas 102 did not show any effect in the MTT assay [45].

Aceneoherqueinones A (104) and B (105), (+)-aceatrovenetinone A (106), and (+)-aceatrovenetinone B (109), along with the known congeners, (+)-scleroderolide (33), (−)-scleroderolide (34), (−)-aceatrovenetinone B (107), and (−)-aceatrovenetinone A (108), were reported from the marine mangrove-derived fungus, Penicillium herquei MA-370. Among these, compounds 104 and 105 were rare phenalenones, having a cyclic ether unit between C-2′ and C-5 (Figure 11). Compounds 106–109 were unstable stereoisomers, possessing configurationally labile chiral centers that were characterized by HPLC-ECD analyses, assisted by TDDFT-ECD calculations. The absolute configuration of 104 was confirmed by X-ray, while those of 105–109 were established by ECD spectra TDDFT-ECD calculations. Compounds 104 and 105 displayed ACE (angiotensin-I-converting enzyme) inhibitory activity (IC50s 3.10 and 11.28 μM, respectively), compared to captopril (IC50 9.23 nM). The molecular docking study revealed that compound 104 bound well with ACE via hydrogen interactions with the residues Gln618, Ala261, Asn624, and Trp621, while 105 interacted with the Tyr360 and Asp358 residues. This difference in interactions was likely caused by the C-8 epimerization of both compounds [46].

Penicillium herquei FT729, which is associated with Hawaiian volcanic soil, yielded herqueilenone A (116) and erabulenols B (117) and C (118) (Figure 12). Their structures were determined by spectroscopic analysis, ECD calculations, and GIAO (gauge-including atomic orbital) NMR chemical shifts. Compounds 117 and 118 exhibited significant IDO1 (indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1) inhibitory activities (with IC50 values of 13.69 and 14.38 µM, respectively), compared to epacadostat (IC50 0.015 µM). Therefore, they can be developed into cancer immunotherapeutics. Compounds 117 and 118 also exhibited a protective effect toward acetaldehyde-induced damage in PC-12 cells and significantly increased cell viability [47].

Figure 12. Structures of compounds 116–123.

Duclauxamide A1 (119), a new polyketide heptacyclic-oligophenalenone dimer with an N-2-hydroxyethyl moiety, was isolated from Penicillium manginii YIM PH30375, which is associated with Panax notoginseng. It belongs to the 9′S-duclauxin epimers, based on spectroscopic data analysis, single-crystal X-ray diffraction, and the computational 13C NMR-DFT method. It is structurally related to duclauxin (120), showing the replacement of the O-atom with the N-containing chain, without modification, on the original carbon skeleton. It showed moderate cytotoxicity toward MCF-7, SMML-7721, A-549, HL-60, and SW480 (IC50 ranged from 11 to 32 μM), compared to cisplatin and paclitaxel [56]. Two new oxaphenalenone dimers, talaromycesones A (121) and B (122), were isolated from the marine fungus Talaromyces sp. LF458 culture broth and mycelia. Their relative configuration was determined by NOESY spectral data. Compound 116 was the first metabolite with a 1-nor oxaphenalenone dimer framework. They exhibited significant antibacterial potential toward S. epidermidis and S. aureus (IC50s 3.70 and 5.48 μM, respectively, for 121, and 17.36 and 19.50, respectively, for 122), compared to chloramphenicol (IC50 1.81 and 2.46 μM, respectively) in the resazurin microplate assay. They revealed no antifungal effectiveness toward Trichophyton rubrum and C. albicans. Moreover, 121 exhibited AchE (acetylcholinesterase) inhibition (IC50 7.49 μM) that was more powerful than huperzine (IC50, 11.60 μM) in the modified Ellman’s enzyme/immunosorbent assay [50].

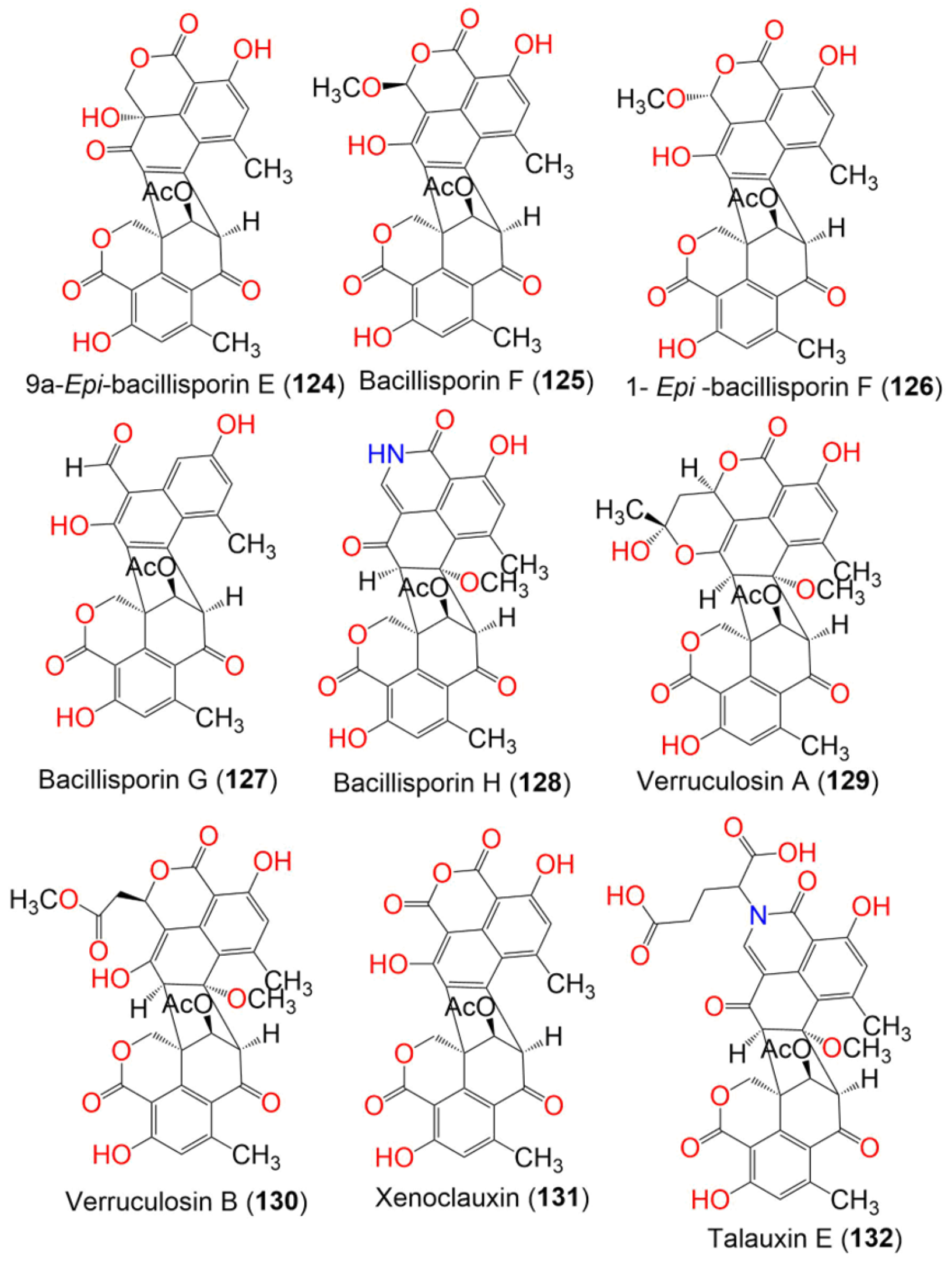

In the case of 9a-epi-bacillisporin E (124) and bacillisporins F–H (125, 127, and 128), new oligophenalenone dimers, along with bacillisporin A (123), were separated from a culture of Talaromyces stipitatus (Figure 13). Their absolute configurations and structures were determined based on spectroscopic analyses, ECD, and GIAO NMR shift calculation, followed by DP4 probability analysis. Only 128 was moderately active (IC50 49.5 µM) toward the HeLa cell, compared to cisplatin (IC50 10.6 µM). No effect was observed on the growth of E. coli (IC50 > 100 μg/mL) for all isolated compounds, while 123 displayed noticeable antibacterial potential versus Staphylococcus hemolyticus, S. aureus (ATCC 6538), and Enterococcus faecalis (MICs 9.5, 5.2, and 2.4 μg/mL, respectively), compared to tetracycline (MICs 29.2, 0.05, and 0.4 μg/mL, respectively). However, 128 had an observable effect on S. aureus (MIC 5.0 μg/mL) when using a microtiter plate assay [51].

Figure 13. The structures of compounds 124–132.

Talaromyces verruculosus yielded two new oligophenalenone dimers, verruculosins A (129) and B (130), and the related known analogs, duclauxin (120), bacillisporin F (125), and xenoclauxin (131) (Figure 13). Compound 129 was a novel oligophenalenone dimer with a unique octacyclic skeleton. Compounds 129 and 130 were fully characterized by spectroscopic, X-ray crystallography, and ECD analyses as well as, optical rotation and NMR calculations. Compounds 120, 125, 129, and 131 exhibited potent CDC25B inhibitory activities (IC50 values of 0.75, 0.40, 0.38, and 0.26 µM, respectively), compared to Na3VO4 (IC50 0.52 µM). In addition, 120 and 129–131 displayed moderate EGFRIC inhibitory activities (IC50 values from 0.24 to 1.22 µM) in comparison to afatinib (IC50 0.0005 µM). The results revealed that oligophenalenone dimers could be used as CDC25B inhibitor candidates [48].

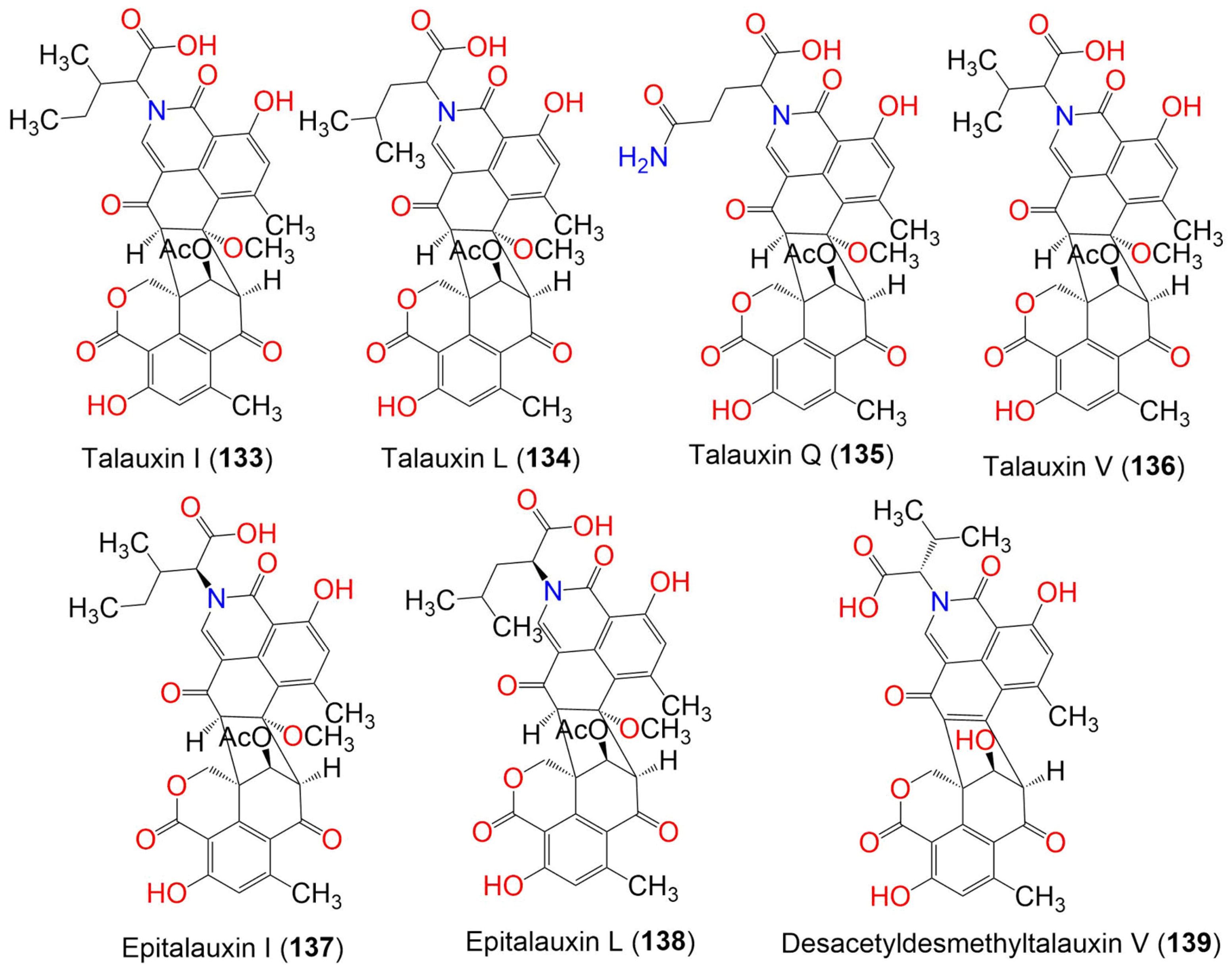

Duclauxin (120), talaromycesone B (122), bacillisporin G (127), and xenoclauxin (131) were isolated from anthill soil fungus Talaromyces sp. IQ-313. They were evaluated for PTP (protein tyrosine phosphatases) inhibitory potential. They inhibited hPTP1B1-400 (IC50 values ranging from 12.7 to 82.1 µM), in comparison to ursolic acid (IC50 26.6 μM. Compounds 120 and 127 displayed the strongest inhibitory activity (IC50 12.7 and 13.5 µM, respectively) [49]. Five new polar pigments, talauxins E (132), I (133), L (134), Q (135), and V (136), along with the previously reported 9-demethyl FR-901235 (55), O-desmethylfunalenone (100), and duclauxin (120), were purified from Talaromyces stipitatus (Figure 14). Talauxins are unusual heterodimers that are produced from the coupling of 120 with amino acids and are closely related to duclauxamide A (119), which was separated from Penicillium manginii [56]. They were fully characterized via spectroscopic and X-ray analysis. Compounds 120 and 132 exhibited weak cytotoxic effectiveness (IC50 140 and 70 μM, respectively) versus NS-1 cells, compared to 5-fluorouracil (IC50 4.6 µM) in the resazurin microplate assay, while 132 also had weak antibacterial potential versus B. subtilis (IC50 265 μM), compared to clotrimazole (IC50 0.4 μM) [43].

Figure 14. The structures of compounds 133–139.

References

- Ibrahim, S.R.M.; Altyar, A.E.; Mohamed, S.G.A.; Mohamed, G.A. Genus Thielavia: Phytochemicals, industrial importance and biological relevance. Nat. Prod. Res. 2021, 36, 5108–5123.

- Ibrahim, S.R.M.; Mohamed, S.G.A.; Altyar, A.E.; Mohamed, G.A. Natural products of the fungal genus Humicola: Diversity, biological activity, and industrial importance. Curr. Microbiol. 2021, 78, 2488–2509.

- Ibrahim, S.R.M.; Mohamed, S.G.A.; Sindi, I.A.; Mohamed, G.A. Biologically active secondary metabolites and biotechnological applications of species of the family Chaetomiaceae (Sordariales): An updated review from 2016 to 2021. Mycol. Prog. 2021, 20, 595–639.

- Ibrahim, S.R.M.; Sirwi, A.; Eid, B.G.; Mohamed, S.G.A.; Mohamed, G.A. Bright Side of Fusarium oxysporum: Secondary Metabolites Bioactivities and Industrial Relevance in Biotechnology and Nanotechnology. J. Fungi. 2021, 7, 943.

- Ibrahim, S.; Sirwi, A.; Eid, B.G.; Mohamed, S.; Mohamed, G.A. Fungal Depsides-Naturally Inspiring Molecules: Biosynthesis, Structural Characterization, and Biological Activities. Metabolites 2021, 11, 683.

- Mohamed, G.A.; Ibrahim, S.R.M. Untapped Potential of Marine—Associated Cladosporium Species: An Overview on Secondary Metabolites, Biotechnological Relevance, and Biological Activities. Mar. Drugs. 2021, 19, 645.

- Al-Rabia, M.W.; Mohamed, G.A.; Ibrahim, S.R.M.; Asfour, H.Z. Anti-inflammatory ergosterol derivatives from the endophytic fungus Fusarium chlamydosporium. Nat. Prod. Res. 2020, 35, 5011–5020.

- Mohamed, G.A.; Ibrahim, S.R.M.; Alhakamy, N.A.; Aljohani, O.S. Fusaroxazin, a novel cytotoxic and antimicrobial xanthone derivative from Fusarium oxysporum. Nat. Prod. Res. 2020, 36, 952–960.

- Mohamed, G.A.; Ibrahim, S.R.M.; El-Agamy, D.S.; Elsaed, W.M.; Sirwi, A.; Asfour, H.Z.; Koshak, A.E.; Elhady, S.S. Terretonin as a New Protective Agent against Sepsis-Induced Acute Lung Injury: Impact on SIRT1/Nrf2/NF-κBp65/NLRP3 Signaling. Biology 2021, 10, 1219.

- Khayat, M.T.; Ibrahim, S.R.M.; Mohamed, G.A.; Abdallah, H.M. Anti-inflammatory metabolites from endophytic fungus Fusarium sp. Phytochem Lett. 2019, 29, 104–109.

- Ibrahim, S.R.M.; Bagalagel, A.A.; Diri, R.M.; Noor, A.O.; Bakhsh, H.T.; Muhammad, Y.A.; Mohamed, G.A.; Omar, A.M. Exploring the activity of fungal phenalenone derivatives as potential CK2 inhibitors using computational methods. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 443.

- Ibrahim, S.R.M.; Mohamed, G.A.; Al Haidari, R.A.; El-Kholy, A.A.; Zayed, M.F.; Khayat, M.T. Biologically active fungal depsidones: Chemistry, biosynthesis, structural characterization, and bioactivities. Fitoterapia 2018, 129, 317–365.

- Hareeri, R.H.; Aldurdunji, M.M.; Abdallah, H.M.; Alqarni, A.A.; Mohamed, S.G.A.; Mohamed, G.A.; Ibrahim, S.R.M. Aspergillus ochraceus: Metabolites, bioactivities, biosynthesis, and biotechnological potential. Molecules 2022, 27, 6759.

- Ibrahim, S.R.M.; Mohamed, G.A.; Khedr, A.M.I. γ-Butyrolactones from Aspergillus species: Structures, biosynthesis, and biological activities. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2017, 12, 791–800.

- Ibrahim, S.R.M.; Abdallah, H.M.; Elkhayat, E.S.; Al Musayeib, N.M.; Asfour, H.Z.; Zayed, M.F.; Mohamed, G.A. Fusaripeptide A: New antifungal and anti-malarial cyclodepsipeptide from the endophytic fungus Fusarium sp. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2018, 20, 75–85.

- Ibrahim, S.R.M.; Mohamed, G.A.; Al Haidari, R.A.; Zayed, M.F.; El-Kholy, A.A.; Elkhayat, E.S.; Ross, S.A. Fusarithioamide B, a new benzamide derivative from the endophytic fungus Fusarium chlamydosporium with potent cytotoxic and antimicrobial activities. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2018, 26, 786–790.

- Ibrahim, S.R.M.; Elkhayat, E.S.; Mohamed, G.A.; Fat’hi, S.M.; Ross, S.A. Fusarithioamide A, a new antimicrobial and cytotoxic benzamide derivative from the endophytic fungus Fusarium chlamydosporium. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2016, 479, 211–216.

- Ibrahim, S.R.; Abdallah, H.M.; Mohamed, G.A.; Ross, S.A. Integracides H–J: New tetracyclic triterpenoids from the endophytic fungus Fusarium sp. Fitoterapia 2016, 112, 161–167.

- Ibrahim, S.R.; Mohamed, G.A.; Ross, S.A. Integracides F and G: New tetracyclic triterpenoids from the endophytic fungus Fusarium sp. Phytochem.Lett. 2016, 15, 125–130.

- Nazir, M.; El Maddah, F.; Kehraus, S.; Egereva, E.; Piel, J.; Brachmann, A.O.; König, G.M. Phenalenones: Insight into the biosynthesis of polyketides from the marine alga-derived fungus Coniothyrium cereale. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015, 13, 8071–8079.

- Elsebai, M.F.; Saleem, M.; Tejesvi, M.V.; Kajula, M.; Mattila, S.; Mehiri, M.; Turpeinen, A.; Pirttilä, A.M. Fungal phenalenones: Chemistry, biology, biosynthesis and phylogeny. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2014, 31, 628–645.

- Chooi, Y.H.; Tang, Y. Navigating the fungal polyketide chemical space: From genes to molecules. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 9933–9953.

- Song, R.; Feng, Y.; Wang, D.; Xu, Z.; Li, Z.; Shao, X. Phytoalexin phenalenone derivatives inactivate mosquito larvae and root-knot nematode as type-II photosensitizer. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42058.

- Hölscher, D.; Dhakshinamoorthy, S.; Alexandrov, T.; Becker, M.; Bretschneider, T.; Buerkert, A.; Crecelius, A.C.; De Waele, D.; Elsen, A.; Heckel, D.G.; et al. Phenalenone-type phytoalexins mediate resistance of banana plants (Musa spp.) to the burrowing nematode Radopholus similis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 105–110.

- Cooke, R.G.; Edwards, J.M. Naturally occurring phenalenones and related compounds. Fortschr. Chem. Org. Nat. 1981, 40, 153–190.

- Harman, R.E.; Cason, J.; Stodola, F.H.; Adkins, A.L. Structural features of herqueinone, a red pigment from Penicillium herquei. J. Org. Chem. 1955, 20, 1260.

- Munde, T.; Brand, S.; Hidalgo, W.; Maddula, R.K.; Svatoš, A.; Schneider, B. Biosynthesis of tetraoxygenated phenylphenalenones in Wachendorfia thyrsiflora. Phytochemistry 2013, 91, 165–176.

- Bucher, G.; Bresolí-Obach, R.; Brosa, C.; Flors, C.; Luis, J.G.; Grillo, T.A.; Nonell, S. β-Phenyl quenching of 9-phenylphenalenones: A novel photocyclisation reaction with biological implications. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 18813–18820.

- Phatangare, K.R.; Lanke, S.K.; Sekar, N. Phenalenone fluorophores-synthesis.; photophysical properties and DFT study. J. Fluoresc. 2014, 24, 1827–1840.

- Lu, R.; Liu, X.; Gao, S.; Zhang, W.; Peng, F.; Hu, F.; Huang, B.; Chen, L.; Bao, G.; Li, C.; et al. New tyrosinase inhibitors from Paecilomyces gunnii. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2014, 62, 11917–11923.

- Rukachaisirikul, V.; Rungsaiwattana, N.; Klaiklay, S.; Phongpaichit, S.; Borwornwiriyapan, K.; Sakayaroj, J. γ-Butyrolactone.; cytochalasin.; cyclic carbonate.; eutypinic acid.; and phenalenone derivatives from the soil fungus Aspergillus sp. PSU-RSPG185. J. Nat. Prod. 2014, 77, 2375–2382.

- Park, S.C.; Julianti, E.; Ahn, S.; Kim, D.; Lee, S.K.; Noh, M.; Oh, D.C.; Oh, K.B.; Shin, A.J. Phenalenones from a marine-derived fungus Penicillium sp. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 176.

- Tansakul, C.; Rukachaisirikul, V.; Maha, A.; Kongprapan, T.; Phongpaichit, S.; Hutadilok-Towatana, N.; Borwornwiriyapan, K.; Sakayaroj, J. A new phenalenone derivative from the soil fungus Penicillium herquei PSU-RSPG93. Nat. Prod. Res. 2014, 28, 1718–1724.

- Li, Q.; Zhu, R.; Yi, W.; Chai, W.; Zhang, Z.; Lian, X.-Y. Peniciphenalenins A–F from the culture of a marine-associated fungus Penicillium sp. ZZ901. Phytochemistry 2018, 152, 53–60.

- Han, Y.; Sun, C.; Li, C.; Zhang, G.; Zhu, T.; Li, D.; Che, Q. Antibacterial phenalenone derivatives from marine-derived fungus Pleosporales sp. HDN1811400. Tetrahedron Lett. 2021, 68, 152938.

- Intaraudom, C.; Nitthithanasilp, S.; Rachtawee, P.; Boonruangprapa, T.; Prabpai, S.; Kongsaeree, P.; Pittayakhajonwut, P. Phenalenone derivatives and the unusual tricyclic sesterterpene acid from the marine fungus Lophiostoma bipolare BCC25910. Phytochemistry 2015, 120, 19–27.

- Macabeo, A.P.G.; Pilapil, L.A.E.; Garcia, K.Y.M.; Quimque, M.T.J.; Phukhamsakda, C.; Cruz, A.J.C.; Hyde, K.D.; Stadler, M. Alpha-glucosidase- and lipase-inhibitory phenalenones from a new species of pseudolophiostoma originating from Thailand. Molecules 2020, 25, 965.

- Zhang, L.-H.; Feng, B.-M.; Sun, Y.; Wu, H.-H.; Li, S.-G.; Liu, B.; Liu, F.; Zhang, W.-Y.; Chen, G.; Bai, J.; et al. Flaviphenalenones A.–C, three new phenalenone derivatives from the fungus Aspergillus flavipes PJ03-11. Tetrahedron Lett. 2016, 57, 645–649.

- Li, Y.; Yue, Q.; Jayanetti, D.R.; Swenson, D.C.; Bartholomeusz, G.A.; An, Z.; Gloer, J.B.; Bills, G.F. Anti-cryptococcus phenalenones and cyclic tetrapeptides from Auxarthron pseudauxarthron. J. Nat. Prod. 2017, 80, 2101–2109.

- Gombodorj, S.; Yang, M.-H.; Shang, Z.-C.; Liu, R.-H.; Li, T.-X.; Yin, G.-P.; Kong, L.-Y. New phenalenone derivatives from Pinellia ternata tubers derived Aspergillus sp. Fitoterapia 2017, 120, 72–78.

- Pang, X.; Zhao, J.Y.; Fang, X.M.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, D.W.; Liu, H.Y.; Su, J.; Cen, S.; Yu, L.Y. Metabolites from the plant endophytic fungus Aspergillus sp. CPCC 400735 and their anti-HIV activities. J. Nat. Prod. 2017, 80, 2595–2601.

- Basnet, B.B.; Liu, L.; Zhao, W.; Liu, R.; Ma, K.; Bao, L.; Ren, J.; Wei, X.; Yu, H.; Wei, J.; et al. New 1,2-naphthoquinone-derived pigments from the mycobiont of lichen Trypethelium eluteriae Sprengel. Nat. Prod. Res. 2019, 33, 2044–2050.

- Chaudhary, N.K.; Crombie, A.; Vuong, D.; Lacey, E.; Piggott, A.M.; Karuso, P. Talauxins: Hybrid phenalenone dimers from Talaromyces stipitatus. J. Nat. Prod. 2020, 83, 1051–1060.

- Kim, D.C.; Minh Ha, T.; Sohn, J.H.; Yim, J.H.; Oh, H. Protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B inhibitors from a marine-derived fungal strain Aspergillus sp. SF-5929. Nat. Prod. Res. 2020, 34, 675–682.

- Zhang, X.; Tan, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yu, M.; Qing, J.; Sun, B.; Niu, S.; Ding, G. Hispidulones A and B, two new phenalenone analogs from desert plant endophytic fungus Chaetosphaeronema hispidulum. J. Antibiot. 2020, 73, 56–59.

- Yang, S.Q.; Mándi, A.; Li, X.M.; Liu, H.; Li, X.; Balázs Király, S.; Kurtán, T.; Wang, B.G. Separation and configurational assignment of stereoisomeric phenalenones from the marine mangrove-derived fungus Penicillium herquei MA-370. Bioorg. Chem. 2021, 106, 104477.

- Yu, J.S.; Li, C.; Kwon, M.; Oh, T.; Lee, T.H.; Kim, D.H.; Ahn, J.S.; Ko, S.K.; Kim, C.S.; Cao, S.; et al. Herqueilenone, A, a unique rearranged benzoquinone-chromanone from the Hawaiian volcanic soil-associated fungal strain Penicillium herquei FT729. Bioorg. Chem. 2020, 105, 104397.

- Wang, M.; Yang, L.; Feng, L.; Hu, F.; Zhang, F.; Ren, J.; Qiu, Y.; Wang, Z. Verruculosins A-B; new oligophenalenone dimers from the soft coral-derived fungus Talaromyces verruculosus. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 516.

- Jiménez-Arreola, B.S.; Aguilar-Ramírez, E.; Cano-Sánchez, P.; Morales-Jiménez, J.; González-Andrade, M.; Medina-Franco, J.L.; Rivera-Chávez, J. Dimeric phenalenones from Talaromyces sp. (IQ-313) inhibit hPTP1B1-400: Insights into mechanistic kinetics from in vitro and in silico studies. Bioorg. Chem. 2020, 101, 103893.

- Wu, B.; Ohlendorf, B.; Oesker, V.; Wiese, J.; Malien, S.; Schmaljohann, R.; Imhoff, J.F. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors from a marine fungus Talaromyces sp. strain LF458. Mar. Biotechnol. 2015, 17, 110–119.

- Zang, Y.; Genta-Jouve, G.; Escargueil, A.E.; Larsen, A.K.; Guedon, L.; Nay, B.; Prado, S. Antimicrobial oligophenalenone dimers from the soil fungus Talaromyces stipitatus. J. Nat. Prod. 2016, 79, 2991–2996.

- Ernst-Russell, M.A.; Chai, C.L.L.; Elix, J.; McCarthy, P.M. Myeloconone A2, a new phenalenone from the lichen Myeloconis erumpens. Aust. J. Chem. 2000, 53, 1011–1013.

- Lee, H.S.; Yu, J.S.; Kim, K.H.; Jeong, G.S. Diketoacetonylphenalenone, derived from Hawaiian volcanic soil-associated fungus Penicillium herquei FT729, regulates T Cell activation via nuclear factor-κB and mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Molecules 2020, 25, 5374.

- Elsebai, M.F.; Ghabbour, H.A.; Mehiri, M. Unusual nitrogenous phenalenone derivatives from the marine-derived fungus Coniothyrium cereale. Molecules 2016, 21, 178.

- Srinivasan, M.; Shanmugam, K.; Kedike, B.; Narayanan, S.; Shanmugam, S.; Gopalasamudram Neelakantan, H. Trypethelone and phenalenone derivatives isolated from the mycobiont culture of Trypethelium eluteriae Spreng and their anti-mycobacterial properties. Nat. Prod. Res. 2020, 34, 3320–3327.

- Cao, P.; Yang, J.; Miao, C.P.; Yan, Y.; Ma, Y.T.; Li, X.N.; Zhao, L.X.; Huang, S.X. New duclauxamide from Penicillium manginii YIM PH30375 and structure revision of the duclauxin family. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 1146–1149.

More

Information

Subjects:

Biotechnology & Applied Microbiology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

852

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

28 Oct 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No