| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Vivi Li | -- | 1757 | 2022-10-26 01:46:43 |

Video Upload Options

Commercial Crew Development (CCDev) is a human spaceflight development program that is funded by the U.S. government and administered by NASA. CCDev will result in US and international astronauts flying to the International Space Station (ISS) on privately operated crew vehicles. Operational contracts to fly astronauts were awarded in September 2014 to SpaceX and Boeing. An uncrewed test flight was performed by each company in 2019. Space-X's Crew Dragon Demo-1 flight of Dragon 2 arrived at the International Space Station in March 2019 and returned via splashdown in the Atlantic Ocean. Due to a Mission Elapsed Time anomaly, the Boeing Orbital Flight Test of the CST-100 spacecraft failed to reach the station in December 2019, but completed some test objectives and performed a safe airbag landing in the New Mexico desert two days after launch. Pending completion of the demonstration flights, each company is contracted to supply six flights to ISS between 2019 and 2024. The first group of astronauts was announced on 3 August 2018.

1. Requirements

Key high-level requirements for the Commercial Crew vehicles include:

- Safely deliver and return four crew members and their equipment to the International Space Station (ISS)[1][2]

- Provide assured crew return in the event of an emergency[1]

- Serve as a 24-hour safe haven in the event of an emergency[1][2]

- Capable of remaining docked to the station for 210 days[1][2]

2. Development Program Overview

After the retirement of STS in 2011, NASA had no domestic vehicles capable of launching astronauts to space.[3] The next major human spaceflight initiative will launch in 2022 as Artemis 2 on the Space Launch System.[4]

In the meantime, NASA continued to send astronauts to the ISS on Soyuz spacecraft seats purchased from Russia.[5] The price has varied over time, with the batch of seats from 2016 to 2017 costing 70.7 million per passenger per flight.[6] The intent of CCDev is to develop safe and reliable commercial ISS crew launch capabilities to replace the Soyuz flights. CCDev follows Commercial Orbital Transportation Services (COTS), an ISS commercial cargo program.[7] CCDev contracts are issued for fixed-price, pay-for-performance milestones.[8]

2.1. CCDev 1

Commercial Crew Development phase 1 (CCDev 1) consisted of $50 million awarded in 2010 to five US companies to develop human spaceflight concepts and technologies.[7][9][10]

NASA awarded development funds to five companies under CCDev 1:

- Blue Origin: $3.7M for a 'pusher' Launch Abort System (LAS) and composite pressure vessels.[11]

- Boeing: $18M for development of the CST-100[12]

- Paragon Space Development Corporation: $1.4M for a plug-and-play environmental control and life support system (ECLSS) Air Revitalization System (ARS) Engineering Development Unit.[13]

- Sierra Nevada Corporation: $20M for development of the Dream Chaser[14]

- United Launch Alliance: $6.7M for an Emergency Detection System (EDS) for human-rating Atlas V[15]

2.2. CCDev 2

On 18 April 2011, NASA awarded nearly $270 million to four companies for developing U.S. vehicles that could fly astronauts after the Space Shuttle fleet's retirement.[16]

Funded proposals:[17]

- Blue Origin: $22 million. Technologies in support of a biconic nose cone design orbital vehicle, including launch abort system liquid oxygen/liquid hydrogen engines.[18][19]

- Sierra Nevada Corporation: $80 million. Dream Chaser

- SpaceX: $75 million. Dragon 2 integrated launch abort system[20]

- Boeing: $92.3 million. Additional CST-100 development[21]

Proposals selected without NASA funding:

- United Launch Alliance: extend development work on human-rating the Atlas V[22]

- Alliant Techsystems (ATK) and Astrium proposed development of Liberty.[23] NASA will share expertise and technology.[24][25]

- Excalibur Almaz Inc. was developing a crewed system with modernized Soviet-era hardware intended for tourism flights to orbit. An unfunded Space Act Agreement to establish a framework to further develop EAI's spacecraft concept for low Earth orbit crew transportation.[26][27]

Proposals not selected:

- Orbital Sciences proposed the Prometheus lifting-body spaceplane vehicle[28]

- Paragon Space Development Corporation proposed additional development of the Commercial Crew Transport-Air Revitalization System.[29]

- t/Space proposed a reusable eight-person crew or cargo transfer spacecraft[30]

- United Space Alliance proposed to commercially fly the two remaining Space Shuttle vehicles.[31]

2.3. CCiCap

Commercial Crew integrated Capability (CCiCap) was originally called CCDev 3.[32] For this phase of the program, NASA wanted proposals to be complete, end-to-end concepts of operation, including spacecraft, launch vehicles, launch services, ground and mission operations, and recovery. In September 2011, NASA released a draft request for proposals (RFP).[33]

The final RFP was released on February 7, 2012, with proposals due on March 23, 2012.[34][35]

The funded Space Act Agreements were awarded on August 3, 2012, and amended on August 15, 2013.[36][37]

The selected proposals were announced 3 August 2012:

- Sierra Nevada Corporation: $212.5 million. Dream Chaser/Atlas V[36]

- SpaceX: $440 million. Dragon 2/Falcon 9[36]

- Boeing: $460 million. CST-100/Atlas V[36]

2.4. CPC Phase 1

The first phase of the Certification Products Contract (CPC) involved the development of a certification plan with engineering standards, tests, and analyses.[38]

Winners of funding of phase 1 of the CPC, announced on December 10, 2012, were:[38]

- Sierra Nevada Corporation: $10 million

- SpaceX: $9.6 million

- Boeing: $9.9 million

2.5. CCtCap - Crew Flights Awarded

The Commercial Crew Transportation Capability (CCtCap) is the second phase of the CPC and included the final development, testing and verifications to allow crewed demonstration flights to the ISS.[38] [39] NASA issued the draft CCtCap contract's Request For Proposals (RFP) on 19 July 2013 with a response date of 15 August 2013.[39]

On 16 September 2014, NASA announced that Boeing and SpaceX had received contracts to provide crewed launch services to the ISS. Boeing could receive up to US$4.2 billion, while SpaceX could receive up to US$2.6 billion.[40] In November 2019 NASA published a first cost per seat estimate: US$55 million for SpaceX's Dragon and US$90 million for Boeing's Starliner. Boeing was also granted an additional $287.2 million above the fixed price contract. Seats on Soyuz had an average cost of US$80 million.[41]

Both the CST-100 Starliner and Crew Dragon will fly an uncrewed flight, then a crewed certification flight, then up to six operational flights to the ISS.[42][43]

3. Timeline

NASA Commercial Crew. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=1736264

3.1. Ongoing Delays

The first flight of the CCDev program was planned to occur in 2015, but insufficient funding caused delays.[44][45][46]

As the spacecraft entered the testing and production phase, technical issues have also caused delays, especially the parachute system, propulsion, and the launch abort system of both capsules.[47]

3.2. Crew Dragon Explosion

On 20 April 2019, an issue arose during a static fire test of Crew Dragon.[48] The accident destroyed the capsule which was planned to be used for the In-Flight Abort Test (IFAT).[49] SpaceX confirmed that the capsule exploded.[50] NASA has stated that the explosion will delay the planned in-flight abort and crewed orbital tests.[51]

4. Test Flights

NASA has ordered twelve operational missions to deliver astronauts to the International Space Station, six with each supplier.[52] Astronaut selections for the first four missions were announced on August 2, 2018.[53]

| Spacecraft | Mission | Description | Crew | Date | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dragon 2 | Dragon 2 pad abort test | Pad abort test, Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Florida | None | 6 May 2015 | Success |

| Dragon 2 |

Crew Dragon Demo-1

|

Uncrewed test flight. DM-1 launched on 2 March 2019 and docked to ISS PMA-2/IDA-2 docking port a little under 24 hours after launch. The Dragon spent five days docked to ISS before undocking and landing on 8 March 2019. | None | 2 March 2019[54] | Success |

| CST-100 Starliner |

Boe-Pad Abort

|

Uncrewed Pad Abort Test | None | 4 November 2019 | Success |

| CST-100 Starliner |

Boe-OFT

|

Uncrewed test flight. Was the first flight of an Atlas V with a dual engine Centaur upper stage. Was originally planned to spend eight days docked to ISS before landing. However, Starliner was unable to rendezvous with the station due to the MET anomaly forcing it to enter a lower-than-expected orbit.[55] The spacecraft returned on 22 December 2019 after spending two days in orbit. | None | 20 December 2019[56] | Partial failure due to a MET anomaly. Rendezvous with ISS cancelled. |

| Dragon 2 |

In-Flight Abort Test

|

A Falcon 9 booster launched a Dragon 2 capsule from LC-39A to perform an in-flight abort shortly after Max q in order to test Dragon 2's launch abort system. Abort occurred at 84 seconds after launch and Dragon 2 successfully separated from the Falcon 9 and flew away using its SuperDraco thrusters. The Falcon 9 booster disintegrated as a result of aerodynamic forces on hollow interstage not normally exposed to such conditions. Dragon 2 splashed down nine minutes after launch after successfully deploying its four parachutes. | None | 19 January 2020 | Success |

| Dragon 2 |

Crew Dragon Demo-2

|

Crewed test flight. Dragon 2 will launch with two crew members and dock to the ISS under 24 hours later. The Dragon will spend one to two weeks docked to the ISS before returning to Earth. | Robert Behnken Douglas Hurley |

April 2020 | Planned |

| CST-100 Starliner |

Boe-CFT

|

Extended crewed test flight, might deliver ISS Expedition 62/63 crew to ISS. | Michael Fincke Christopher Ferguson Nicole Aunapu Mann |

NET Mid 2020[57] | Planned |

5. ISS Crew Rotation Flights

| Spacecraft | Mission | Description | Crew | Date | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crew Dragon | USCV-1 | Deliver ISS Expedition 64/65 crew | Michael S. Hopkins Victor Glover Soichi Noguchi |

July 2020 | Planned |

| CST-100 Starliner | USCV-2 | Deliver ISS Expedition 66/67 crew. Would be only the fourth US Spaceflight to have a female Commander. | Sunita Williams Josh Cassada Thomas Pesquet Andrei Borisenko |

December 2020 | Planned |

| Crew Dragon | USCV-3 | Will transport four astronauts to the ISS who will spend 6 months aboard the ISS. | May 2021 | Planned |

6. Funding Summary

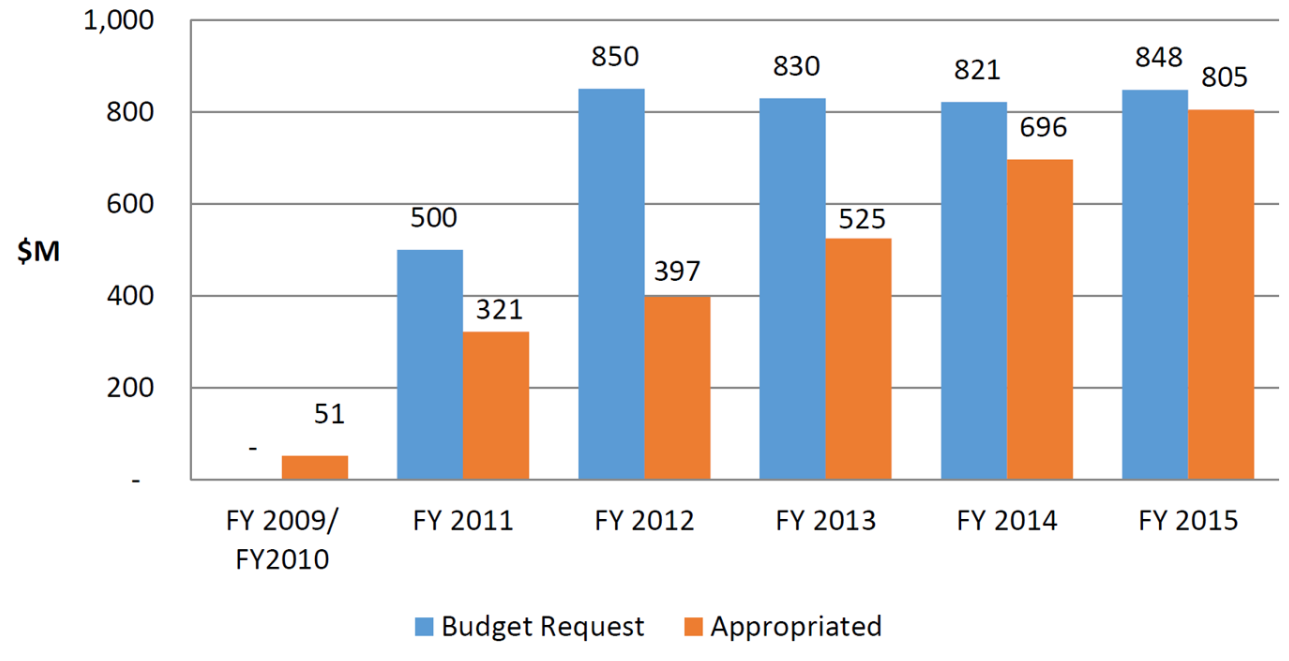

The first flight of the CCDev program was planned to occur in 2015, but insufficient funding caused delays.[44][46]

For the fiscal year (FY) 2011 budget, US$500 million was requested for the CCDev program, but Congress granted only $270 million.[58] For the FY 2012 budget, $850 million was requested and $406 million approved.[45] For the FY 2013 budget, 830 million was requested and $488 million approved.[59] For the FY 2014 budget, $821 million was requested and $696 million approved.[44][60] In FY 2015, $848 million was requested and $805 million, or 95%, was approved.[61]

The funding of all commercial crew contractors for each phase of the CCP program is as follows—CCtCap values are maxima and include post-development operational flights.

| Round (years) |

CCDev1[62] (2010–2011) |

CCDev2[63][64] (2011–2012) |

CCiCap[36][37] (2012–2014) |

CPC1[38] (2013–2014) |

CCtCap[43] (2014-current) |

Total (2010–current[needs update] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manufacturers of spacecraft | ||||||

| Boeing | 18.0 | 112.9 | 480.0 | 9.9 | 4,200.0 | 4,820.9 |

| SpaceX | – | 75.0 | 460.0 | 9.6 | 2,600.0 | 3,144.6 |

| Sierra Nevada Corporation | 20.0 | 105.6 | 227.5 | 10.0 | – | 362.1 |

| Blue Origin | 3.7 | 22.0 | – | – | – | 25.7 |

| Manufacturers of launch vehicles and equipment | ||||||

| United Launch Alliance | 6.7 | - | – | – | – | 6.7 |

| Paragon Space Development Corporation | 1.4 | – | – | – | – | 1.4 |

| Total: | 49.8 | 315.5 | 1,167.5 | 29.6 | 6,800.0 | 8,362.4 |

On November 14, 2019, NASA's inspector general published an auditing report listing per-seat prices of $90 million for Starliner and $55 million for Dragon Crew. With these, Boeing's price is higher than what NASA has paid the Russian space corporation, Roscosmos, for Soyuz spacecraft seats to fly US and partner-nation astronauts to the space station. The report also states that NASA agreed to pay an additional $287.2 million above Boeing's fixed prices to mitigate a perceived 18-month gap in ISS flights anticipated in 2019 and to ensure the contractor continued as a second commercial crew provider, without offering similar opportunities to SpaceX.[65]

References

- Bayt, Rob (July 26, 2011). "Commercial Crew Program: Key Driving Requirements Walkthrough". NASA. Archived from the original on March 28, 2012. https://web.archive.org/web/20120328055242/http://commercialcrew.nasa.gov/document_file_get.cfm?docid=107. Retrieved July 27, 2011.

- "Commercial Crew Program – fact sheet". NASA. February 2012. http://www.nasa.gov/pdf/660622main_2012.06.18_CCP.pdf. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

- Denise Chow (April 14, 2011). "NASA Faces Awkward, Unfortunate Spaceflight Gap". Space.com. https://www.space.com/11387-nasa-future-human-spaceflight-hurdles-nss27.html. Retrieved August 10, 2018.

- Daines, Gary (December 1, 2016). "First Flight With Crew Will Mark Important Step on Journey to Mars". https://www.nasa.gov/feature/nasa-s-first-flight-with-crew-will-mark-important-step-on-journey-to-mars.

- "NASA officials mulling the possibility of purchasing Soyuz seats for 2019". https://arstechnica.com/science/2016/09/nasa-officials-mulling-the-possibility-of-purchasing-soyuz-seats-for-2019/.

- "NASA to Pay $70 Million a Seat to Fly Astronauts on Russian Spacecraft". http://www.space.com/20897-nasa-russia-astronaut-launches-2017.html.

- "Selection Statement For Commercial Crew Development". JSC-CCDev-1. NASA. December 9, 2008. http://hobbyspace.com/AAdmin/archive/Reference/CCDev_Source_Selection_Statement_signed-1.pdf. Retrieved February 10, 2011.

- "Moving Forward: Commercial Crew Development Building the Next Era in Spaceflight". Rendezvous. NASA. 2010. pp. 10–17. http://www.nasa.gov/pdf/475795main_rendezvous_v4n3.pdf. Retrieved February 14, 2011. ""Just as in the COTS projects, in the CCDev project we have fixed-price, pay-for-performance milestones," Thorn said. "There's no extra money invested by NASA if the projects cost more than projected.""

- "NASA Selects Commercial Firms to Begin Development of Crew Transportation Concepts and Technology Demonstrations for Human Spaceflight Using Recovery Act Funds". press release (NASA). February 1, 2010. http://www.nasa.gov/home/hqnews/2010/feb/HQ_C10-004_Commercia_Crew_Dev.html. Retrieved February 2, 2010.

- "Commercial Crew and Cargo Program". Archived from the original on March 5, 2010. https://web.archive.org/web/20100305034240/http://www.aiaa.org/pdf/industry/presentations/Lindenmoyer_C3PO.pdf.

- Jeff Foust. "Blue Origin proposes orbital vehicle". http://www.newspacejournal.com/2010/02/18/blue-origin-proposes-orbital-vehicle/.

- NASA Selects Boeing for American Recovery and Reinvestment Act Award to Study Crew Capsule-based Design, http://boeing.mediaroom.com/index.php?s=43&item=1054

- "CCDev Information". NASA. July 20, 2010. http://www.nasa.gov/offices/c3po/partners/ccdev_info.html.

- "SNC receives largest award of NASA's CCDev Competitive Contract". SNC. February 1, 2010. Archived from the original on February 7, 2010. https://web.archive.org/web/20100207081838/http://sncorp.com/news/press/pr10/snc_ccdev_spacenews.shtml.

- "NASA Selects United Launch Alliance for Commercial Crew Development Program". February 2, 2010. http://www.ulalaunch.com/site/pages/News.shtml#/45.

- Dean, James. "NASA awards $270 million for commercial crew efforts". space.com, April 18, 2011. https://web.archive.org/web/20110511143351/http://space.flatoday.net/2011/04/nasa-awards-270-million-for-commercial.html

- Morring, Frank, Jr. (2011-04-22). "Five Vehicles Vie To Succeed Space Shuttle". Aviation Week. Archived from the original on December 21, 2011. https://web.archive.org/web/20111221070704/http://www.aviationweek.com/aw/generic/story_generic.jsp?channel=awst&id=news%2Fawst%2F2011%2F04%2F25%2FAW_04_25_2011_p24-313867.xml&headline=Five%20Vehicles%20Vie%20To%20Succeed%20Space%20Shuttle. Retrieved 2011-02-23. "the CCDev-2 awards, ... went to Blue Origin, Boeing, Sierra Nevada Corp. and Space Exploration Technologies Inc. (SpaceX)."

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on February 15, 2013. https://web.archive.org/web/20130215051509/http://procurement.ksc.nasa.gov/documents/NNK11MS02S_SAA_BlueOrigin_04-18-2011.pdf. Retrieved 2013-12-05. , p. 2-1

- " Blue Origin Technology" . Blue Origin. Retrieved February 1, 2016. https://www.blueorigin.com/technology

- "Taking the next step: Commercial Crew Development Round 2". SpaceX Updates webpage. SpaceX. 2010-01-17. http://www.spacex.com/updates.php. Retrieved 2011-01-17.

- Boeing Submits Proposal for 2nd Round Of Commercial Crew Dev. moonandback.com spaceflight news, December 14, 2010, accessed December 27, 2010. http://moonandback.com/2010/12/14/boeing-submits-proposal-for-2nd-round-of-commercial-crew-dev/

- "NASA Begins Commercial Partnership With United Launch Alliance". NASA. http://www.nasa.gov/centers/kennedy/news/releases/2011/release-20110718.html. Retrieved 18 July 2011.

- Malik, Tariq (2010-02-08). "Scrapped NASA Rocket May be Resurrected for Commercial Launches". SPACE.com. http://www.space.com/10792-liberty-rocket-ressurects-scrapped-nasa-ares1.html. Retrieved 2010-02-10.

- "NASA, private firm may team up on Liberty rocket". USA Today. https://www.usatoday.com/tech/science/space/story/2011-09-13/NASA-atk-liberty-rocket/50386970/1. Retrieved 2011-09-13.

- "Commercial Crew Program Forum Presentation" , p. 7. commercialcrew.nasa.gov, September 16, 2011. http://commercialcrew.nasa.gov/document_file_get.cfm?docid=278

- "CCP and Excalibur Sign Space Act Agreement". NASA. http://www.nasa.gov/exploration/commercial/CCP-Excalibur.html.

- "Excalibur Almaz, NASA sign commercial spaceflight deal" http://www.floridatoday.com/article/20111103/NEWS02/311030050/Excalibur-Almaz-NASA-sign-commercial-spaceflight-deal

- "The Shape of Things to Come – Orbital's Prometheus™ Space Plane Ready for NASA's Commercial Crew Development Initiative". http://www.orbital.com/NewsInfo/Publications/OrbitalQuarterly_Winter2011.pdf?prid=762#search=%22prometheus%22.

- "(press release) Paragon Space Development Corporation Completes All Development Milestones on the NASA Commercial Crew Development Program". Paragon. 2011-01-31. Archived from the original on July 15, 2011. https://web.archive.org/web/20110715043642/http://www.paragonsdc.com/docs/CCT-ARS%20Press%20Release.pdf.

- Boyle, Alan (2011-02-11). "Let's talk about the final frontier". Cosmic Log. MSNBC. Archived from the original on February 15, 2011. https://web.archive.org/web/20110215002006/http://cosmiclog.msnbc.msn.com/_news/2011/02/11/6035600-lets-talk-about-the-final-frontier. Retrieved 2011-02-13. "the proposal calls for the development of a spaceship that could be sent into space on a variety of launch vehicles. ... "Up to eight crew, Soyuz-like architecture (recoverable reusable crew element, expendable orbital/cargo module). Incorporates HMX's patented integral abort system (uses OMS/RCS propellant in separate abort engines). Can fly on Atlas 401 [a configuration for the Atlas 5 rocket], F9 [SpaceX's Falcon 9] or Taurus II (enhanced) but with a reduced cargo and crew capability on the latter vehicle. Goal is to be the lowest-price provider on a per-seat basis. Nominal land recovery with water backup.""

- "NASA weighs plan to keep shuttle until 2017 – Technology & science – Space – NBC News". NBC News. http://www.nbcnews.com/id/41397955.

- "COMMERCIAL CREW INTEGRATED CAPABILITY". NASA. 2012-01-23. https://www.fbo.gov/index?s=opportunity&mode=form&id=230715a3035c3af460f542da1ad80562&tab=core&_cview=0. Retrieved 25 January 2012.

- "Statement of William H. Gerstenmaier, Associate Administrator for Human Exploration and Operations, National Aeronautics and Space Administration; before the Subcommittee on Space and Aeronautics Committee on Science, Space and Technology; U. S. House of Representatives". October 12, 2011. pp. 6–7. http://science.house.gov/sites/republicans.science.house.gov/files/documents/hearings/101211_Gerstenmaier.pdf.

- "CCiCap Solicitation". NASA. 2012-02-07. Archived from the original on February 16, 2013. https://web.archive.org/web/20130216214755/http://prod.nais.nasa.gov/cgi-bin/eps/sol.cgi?acqid=149848. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- "Commercial Crew Integrated Capability Pre-Proposal Conference". NASA. February 14, 2012. Archived from the original on February 17, 2013. https://web.archive.org/web/20130217052232/http://commercialcrew.nasa.gov/document_file_get.cfm?docid=579. Retrieved February 14, 2012.

- "NASA Announces Next Steps in Effort to Launch Americans from U.S. Soil". NASA. August 3, 2012. http://www.nasa.gov/centers/kennedy/news/releases/2012/release-20120803.html. Retrieved August 3, 2012.

- "NASA Announces Additional Commercial Crew Development Milestones". Space Ref. SpaceRef Interactive Inc.. August 15, 2013. http://spaceref.biz/2013/08/nasa-announces-additional-commercial-crew-development-milestones.html. Retrieved August 16, 2013.

- "NASA Awards Contracts In Next Step Toward Safely Launching American Astronauts From U.S. Soil". NASA. 10 December 2012. http://www.nasa.gov/centers/kennedy/news/releases/2012/release-20121210.html. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- "NASA Commercial Crew Transportation Capability Contract CCTCAP Draft RFP". SpaceREF. July 19, 2013. http://www.spaceref.com/news/viewsr.html?pid=44387. Retrieved July 22, 2013.

- Bolden, Charlie. "American Companies Selected to Return Astronaut Launches to American Soil". http://blogs.nasa.gov/bolden/2014/09/16/american-companies-selected-to-return-astronaut-launches-to-american-soil/. Retrieved September 16, 2014.

- "NASA report finds Boeing seat prices are 60% higher than SpaceX". November 14, 2019. https://arstechnica.com/science/2019/11/nasa-report-finds-boeing-seat-prices-are-60-higher-than-spacex/.

- Foust, Jeff (2014-09-19). "NASA Commercial Crew Awards Leave Unanswered Questions". Space News. http://www.spacenews.com/article/civil-space/41924nasa-commercial-crew-awards-leave-unanswered-questions. Retrieved 2014-09-21. ""We basically awarded based on the proposals that we were given," Kathy Lueders, NASA commercial crew program manager, said in a teleconference with reporters after the announcement. "Both contracts have the same requirements. The companies proposed the value within which they were able to do the work, and the government accepted that.""

- "RELEASE 14-256 NASA Chooses American Companies to Transport U.S. Astronauts to International Space Station". NASA. http://www.nasa.gov/press/2014/september/nasa-chooses-american-companies-to-transport-us-astronauts-to-international. Retrieved 29 October 2014.

- Norris, Guy (31 May 2013). "NASA Chief Repeats Warnings On Commercial Crew Delays". https://aviationweek.com/defense-space/space/nasa-chief-repeats-commercial-crew-warning.

- Clark, Stephen (2011-11-23). "Reduced budget threatens delay in private spaceships". Spaceflightnow. http://spaceflightnow.com/news/n1111/23commercialcrew/. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- "CSF President Michael Lopez-Alegria Statement on NASA Contract Extension with Roscosmos". Commercial Spaceflight Federation. 2 May 2013. http://www.commercialspaceflight.org/2013/05/csf-president-michael-lopez-alegria-statement-on-nasa-contract-extension-with-roscosmos/. Retrieved 2 May 2013.

- "NASA's management of crew transportation to the International Space Station". NASA Office of Audits. November 14, 2019. p. 3. https://oig.nasa.gov/docs/IG-20-005.pdf.

- Bridenstine, Jim. "NASA has been notified about the results of the @SpaceX Static Fire Test and the anomaly that occurred during the final test. We will work closely to ensure we safely move forward with our Commercial Crew Program.". https://twitter.com/JimBridenstine/status/1119754804258062337. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- Gebhardt, Chris (August 11, 2017). "SpaceX and Boeing in home stretch for Commercial Crew readiness". NASASpaceFlight.com. https://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2017/08/spacex-boeing-home-stretch-commercial-crew-readiness/. Retrieved August 17, 2017.

- Mosher, Dave. "SpaceX confirmed that its Crew Dragon spaceship for NASA was 'destroyed' by a recent test. Here's what we learned about the explosive failure.". https://www.businessinsider.com/spacex-crew-dragon-spaceship-test-explosion-2019-5.

- "NASA boss says no doubt SpaceX explosion delays flight program". June 18, 2019. https://www.journalpioneer.com/news/world/nasa-boss-says-no-doubt-spacex-explosion-delays-flight-program-323465/.

- "Boeing, SpaceX Secure Additional Crewed Missions Under NASA's Commercial Space Transport Program". https://www.govconwire.com/2017/01/boeing-spacex-secure-additional-crewed-missions-under-nasas-commercial-space-transport-program/.

- "NASA Assigns Crews to First Test Flights, Missions on Commercial Spacecraft". NASA. August 3, 2018. https://www.nasa.gov/press-release/nasa-assigns-crews-to-first-test-flights-missions-on-commercial-spacecraft.

- "Demo-1 Flight Readiness Concludes" (in en-US). https://blogs.nasa.gov/commercialcrew/2019/02/22/demo-1-flight-readiness-concludes/.

- Bridenstine, Jim (2019-12-20). "Update: #Starliner had a Mission Elapsed Time (MET) anomaly causing the spacecraft to believe that it was in an orbital insertion burn, when it was not. More information at 9am ET:http://NASA.gov/live" (in en). https://twitter.com/JimBridenstine/status/1208020657583341569?s=19.

- Foust, Jeff. "Boeing, SpaceX press towards commercial crew test flights this year". https://spacenews.com/boeing-spacex-press-towards-commercial-crew-test-flights-this-year/. Retrieved 9 October 2019.

- "Launch Schedule". January 17, 2020. https://spaceflightnow.com/launch-schedule/.

- "Senate Panel Cuts Commercial Crew, Adds Funds for Orion and Heavy Lift". Space News. July 21, 2010. http://www.spacenews.com/civil/072110senate-panel-cuts-commercial-crew-adds-funds-for-orion-and-heavy-lift.html. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- McAlister, Phillip (18 April 2013). "Commercial Spaceflight Update". NASA. http://www.nasa.gov/pdf/742926main_20130419_heoc_mcalisiter%20=TAGGED.pdf. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- Joe Pappalardo (September 16, 2014). "Is the Relationship Between NASA and Private Space About to Sour?". Popular Mechanics. http://www.popularmechanics.com/science/space/nasa/is-the-relationship-between-nasa-and-private-space-about-to-sour-16441487.

- Clark, Stephen (2014-12-14). "NASA gets budget hike in spending bill passed by Congress". Spaceflight Now. http://spaceflightnow.com/2014/12/14/nasa-gets-budget-hike-in-spending-bill-passed-by-congress/. Retrieved 2014-12-15.

- "NASA Selects Commercial Firms to Begin Development of Crew Transportation Concepts and Technology Demonstrations for Human Spaceflight Using Recovery Act Funds". press release (NASA). February 1, 2010. http://www.nasa.gov/home/hqnews/2010/feb/HQ_C10-004_Commercia_Crew_Dev.html. Retrieved June 9, 2012.

- "NASA Awards Next Set Of Commercial Crew Development Agreements". press release (NASA). April 18, 2011. http://www.nasa.gov/offices/c3po/home/agreementsfeature.html. Retrieved June 9, 2012.

- "NASA Releases Commercial Crew Draft RFP, Announces CCDEV2 Optional Milestones". press release (NASA). September 19, 2011. http://www.nasa.gov/home/hqnews/2011/sep/HQ_11-312_CCDEV_Announ.html. Retrieved June 9, 2012.

- BERGER, ERIC. "NASA report finds Boeing seat prices are 60% higher than SpaceX". https://arstechnica.com/science/2019/11/nasa-report-finds-boeing-seat-prices-are-60-higher-than-spacex/?comments=1. Retrieved 14 November 2019.