| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Camila Xu | -- | 5853 | 2022-10-24 01:40:55 |

Video Upload Options

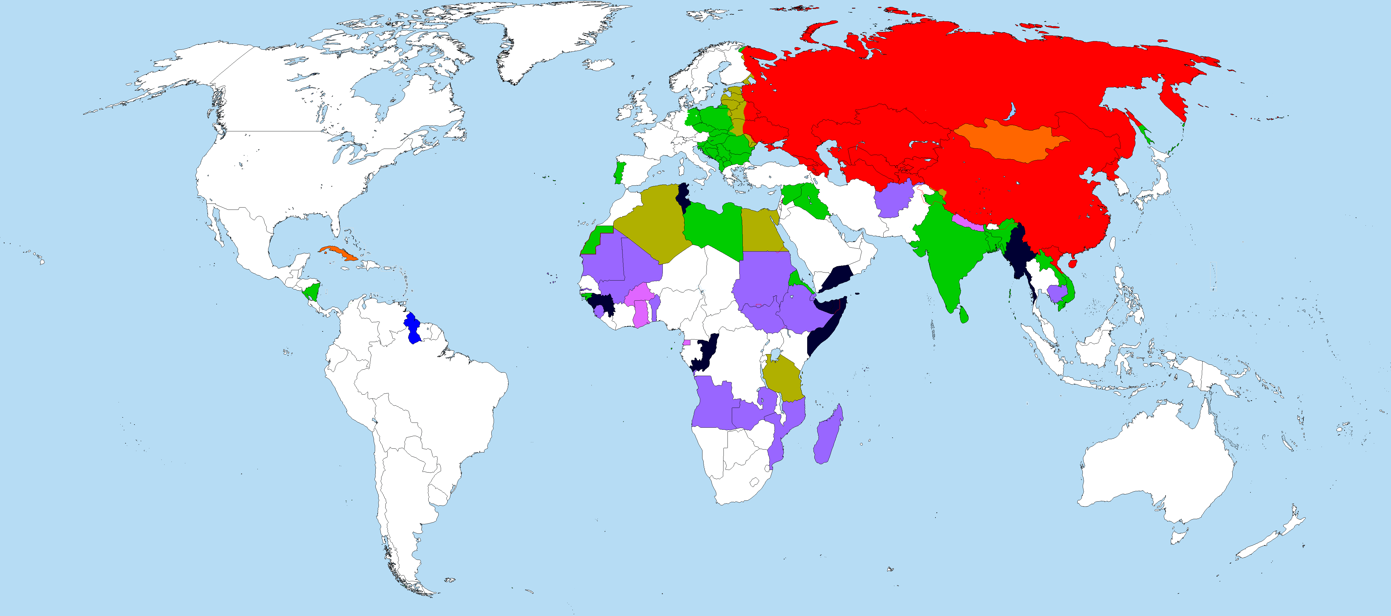

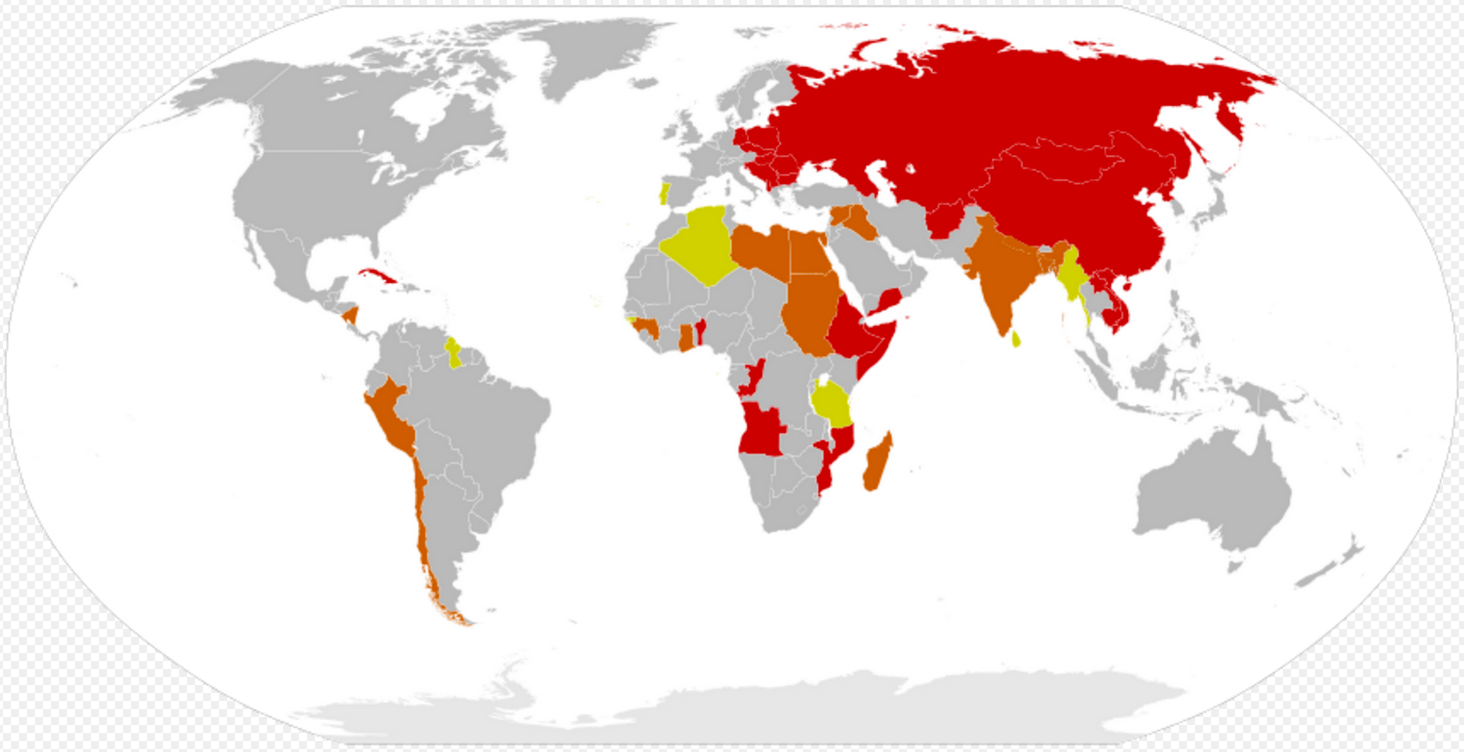

A socialist state, socialist republic, or socialist country, sometimes referred to as a workers' state or workers' republic, is a sovereign state constitutionally dedicated to the establishment of socialism. The term communist state is often used synonymously in the West specifically when referring to one-party socialist states governed by Marxist–Leninist communist parties, despite these countries being officially socialist states in the process of building socialism. These countries never describe themselves as communist nor as having implemented a communist society. Additionally, a number of countries that are multi-party capitalist states make references to socialism in their constitutions, in most cases alluding to the building of a socialist society, naming socialism, claiming to be a socialist state, or including the term people's republic or socialist republic in their country's full name, although this does not necessarily reflect the structure and development paths of these countries' political and economic systems. Currently, these countries include Algeria, Bangladesh, Guyana, India, Nepal, Nicaragua, Portugal, Sri Lanka and Tanzania. The idea of a socialist state stems from the broader notion of state socialism, the political perspective that the working class needs to use state power and government policy to establish a socialised economic system. This may either mean a system where the means of production, distribution and exchange are nationalised or under state ownership, or simply a system in which social values or workers' interests have economic priority. However, the concept of a socialist state is mainly advocated by Marxist–Leninists and most socialist states have been established by political parties adhering to Marxism–Leninism or some national variation thereof such as Maoism, Stalinism or Titoism. A state, whether socialist or not, is opposed the most by anarchists, who reject the idea that the state can be used to establish a socialist society due to its hierarchical and arguably coercive nature, considering a socialist state or state socialism as an oxymoron. The concept of a socialist state is also considered unnecessary or counterproductive and rejected by some classical, libertarian and orthodox Marxists, libertarian socialists and other socialist political thinkers who view the modern state as a byproduct of capitalism which would have no function in a socialist system. A socialist state is to be distinguished from a multi-party liberal democracy governed by a self-described socialist party, where the state is not constitutionally bound to the construction of socialism. In such cases, the political system and machinery of government is not specifically structured to pursue the development of socialism. Socialist states in the Marxist–Leninist sense are sovereign states under the control of a vanguard party which is organizing the country's economic, political and social development toward the realization of socialism. Economically, this involves the development of a state capitalist economy with state-directed capital accumulation with the long-term goal of building up the country's productive forces while simultaneously promoting world communism. Academics, political commentators and other scholars tend to distinguish between authoritarian socialist and democratic socialist states, with the first representing the Soviet Bloc and the latter representing Western Bloc countries which have been democratically governed by socialist parties such as Britain, France, Sweden and Western social-democracies in general, among others.

1. Overview

The first socialist state was the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic, established in 1917.[1] In 1922, it merged with the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic, the Transcaucasian Soviet Federal Socialist Republic and the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic into a single federal union called the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). The Soviet Union proclaimed itself a socialist state and proclaimed its commitment to building a socialist economy in its 1936 constitution and a subsequent 1977 constitution. It was governed by the Communist Party of the Soviet Union as a single-party state ostensibly with a democratic centralism organization, with Marxism–Leninism remaining its official guiding ideology until Soviet Union's dissolution on 26 December 1991. The political systems of these Marxist–Leninist socialist states revolve around the central role of the party which holds ultimate authority. Internally, the communist party practices a form of democracy called democratic centralism.[2]

During the 22nd Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in 1961, Nikita Khrushchev announced the completion of socialist construction and declared the optimistic goal of achieving communism in twenty years.[3] The Eastern Bloc was a political and economic bloc of Soviet-aligned socialist states in Eastern and Central Europe which adhered to Marxism–Leninism, Soviet-style governance and economic planning in the form of the administrative-command system and command economy. China's socio-economic structure has been referred to as "nationalistic state capitalism" and the Eastern Bloc (Eastern Europe and the Third World) as "bureaucratic-authoritarian systems."[4][5]

The People's Republic of China was founded on 1 October 1949 and proclaims itself to be a socialist state in its 1982 constitution. The Democratic People's Republic of Korea (North Korea) used to be a Marxist–Leninist state. In 1972, the country adopted a new constitution which changed the official state ideology to Juche which is held to be a distinct Korean re-interpretation of the former ideology.[6] Similarly, direct references to communism in the Lao People's Democratic Republic are not included in its founding documents, although it gives direct power to the governing ruling party, the Marxist–Leninist Lao People's Revolutionary Party. The preamble to the constitution of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam states that Vietnam only entered a transition stage between capitalism and socialism after the country was reunified under the Communist Party of Vietnam in 1976.[7] The 1992 constitution of the Republic of Cuba states that the role of the Communist Party of Cuba is to "guide the common effort toward the goals and construction of socialism (and the progress toward a communist society)".[8] The 2019 constitution retains the aim to work towards the construction of socialism.[9]

A number of countries make reference to socialism in their constitutions that are not single-party states embracing Marxism–Leninism and planned economies. In most cases, these are constitutional references to the building of a socialist society and political principles that have little to no bearing on the structure and guidance of these country's machinery of government and economic system. The preamble to the 1976 Constitution of Portugal states that the Portuguese state has as one of its goals opening "the way to socialist society".[10] Algeria, the Congo, India and Sri Lanka have directly used the term socialist in their official constitution and name. Croatia, Hungary and Poland directly denounce "Communism" in their founding documents in reference to their past regimes.[11][12][13]

In these cases, the intended meaning of socialism can vary widely and sometimes the constitutional references to socialism are left over from a previous period in the country's history. In the case of many Middle Eastern states, the term socialism was often used in reference to an Arab socialist/nationalist philosophy adopted by specific regimes such as that of Gamal Abdel Nasser and that of the various Ba'ath parties. Examples of countries directly using the term socialist in their names include the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka and the Socialist Republic of Vietnam while a number of countries make references to socialism in their constitutions, but not in their names. These include India[14] and Portugal. In addition, countries such as Belarus, Colombia, France, Russia and Spain use the varied term social state, leaving a more ambiguous meaning. In the constitutions of Croatia, Hungary and Poland, direct condemnation is made to the respective past socialist regimes. The autonomous region of Rojava which operates under the principles of democratic confederalism has been described as a socialist state.[15]

1.2. Other Uses

During the post-war consensus, nationalization of large industries was relatively widespread and it was not uncommon for commentators to describe some European countries as democratic socialist states seeking to move their countries toward a socialist economy.[16][17][18][19] In 1956, leading British Labour Party politician and author Anthony Crosland claimed that capitalism had been abolished in Britain, although others such as Welshman Aneurin Bevan, Minister of Health in the first post-war Labour government and the architect of the National Health Service, disputed the claim that Britain was a socialist state.[20][21] For Crosland and others who supported his views, Britain was a socialist state. According to Bevan, Britain had a socialist National Health Service which stood in opposition to the hedonism of Britain's capitalist society, making the following point:

The National Health service and the Welfare State have come to be used as interchangeable terms, and in the mouths of some people as terms of reproach. Why this is so it is not difficult to understand, if you view everything from the angle of a strictly individualistic competitive society. A free health service is pure Socialism and as such it is opposed to the hedonism of capitalist society.[22]

Although as in the rest of Europe the laws of capitalism still operated fully and private enterprise dominated the economy,[23] some political commentators claimed that during the post-war period, when socialist parties were in power, countries such as Britain and France were democratic socialist states and the same is now applied to the Nordic countries and the Nordic model.[16][17][18][19] In the 1980s, the government of President François Mitterrand aimed to expand dirigisme and attempted to nationalize all French banks, but this attempt faced opposition of the European Economic Community because it demanded a free-market capitalist economy among its members.[24][25] Nevertheless, public ownership in France and the United Kingdom during the height of nationalization in the 1960s and 1970s never accounted for more than 15–20% of capital formation, further dropping to 8% in the 1980s and below 5% in the 1990s after the rise of neoliberalism.[23]

The socialist policies practiced by parties such as the Singaporean People's Action Party (PAP) during its first few decades in power were of a pragmatic kind as characterized by its rejection of nationalization. Despite this, the PAP still claimed to be a socialist party, pointing out its regulation of the private sector, state intervention in the economy and social policies as evidence of this.[26] The Singaporean prime minister Lee Kuan Yew also stated that he has been influenced by the democratic socialist British Labour Party.[27]

1.3. Terminology

Because most existing socialist states operated along Marxist–Leninist principles of governance, the terms Marxist–Leninist regime and Marxist–Leninist state are used by scholars, particularly when focusing on the political systems of these countries.[2] A people's republic is a type of socialist state with a republican constitution. Although the term initially became associated with populist movements in the 19th century such as the German Völkisch movement and the Narodniks in Russia, it is now associated to communist states. A number of the short-lived communist states which formed during World War I and its aftermath called themselves people's republics. Many of these sprang up in the territory of the former Russian Empire following the October Revolution.[28][29][30][31][32] Additional people's republics emerged following the Allied victory in World War II, mainly within the Eastern Bloc.[33][34][35][36][37][38][39] In Asia, China became a people's republic following the Chinese Communist Revolution[40] and North Korea also became a people's republic.[41] During the 1960s, Romania and Yugoslavia ceased to use the term people's republic in their official name, replacing it with the term socialist republic as a mark of their ongoing political development. Czechoslovakia also added the term socialist republic into its name during this period. It had become a people's republic in 1948, but the country had not used that term in its official name.[42] Albania used both terms in its official name from 1976 to 1991.[43]

The term socialist state is widely used by Marxist–Leninist parties, theorists and governments to mean a state under the control of a vanguard party that is organizing the economic, social and political affairs of said state toward the construction of socialism. States run by communist parties that adhere to Marxism–Leninism, or some national variation thereof, refer to themselves as socialist states or workers and peasants' states. They involve the direction of economic development toward the building up of the productive forces to underpin the establishment of a socialist economy and usually include that at least the commanding heights of the economy are nationalized and under state ownership.[44][45] This may or may not include the existence of a socialist economy, depending on the specific terminology adopted and level of development in specific countries. The Leninist definition of a socialist state is a state representing the interests of the working class which presides over a state capitalist economy structured upon state-directed accumulation of capital with the goal of building up the country's productive forces and promoting worldwide socialist revolution while the realization of a socialist economy is held as the long-term goal.[44]

In the Western world, particularly in mass media, journalism and politics, these states and countries are often called communist states (although they do not use this term to refer to themselves), despite the fact that these countries never claimed to have achieved communism in their countries—rather, they claim to be building and working toward the establishment of socialism and the development towards communism thereafter in their countries.[46][47][48][49] Terms used by communist states include national-democratic, people's democratic, people's republican, socialist-oriented and workers and peasants' states.[50]

2. Political Theories

2.1. Marxist Theory of the State

Karl Marx and subsequent thinkers in the Marxist tradition conceive of the state as representing the interests of the ruling class, partially out of material necessity for the smooth operation of the modes of production it presides over. Marxists trace the formation of the contemporary form of the sovereign state to the emergence of capitalism as a dominant mode of production, with its organizational precepts and functions designed specifically to manage and regulate the affairs of a capitalist economy. Because this involves governance and laws passed in the interest of the bourgeoisie as a whole and because government officials either come from the bourgeoisie or are dependent upon their interests, Marx characterized the capitalist state as a dictatorship of the bourgeoisie. Extrapolating from this, Marx described a post-revolutionary government on the part of the working class or proletariat as a dictatorship of the proletariat because the economic interests of the proletariat would have to guide state affairs and policy during a transitional state. Alluding further to the establishment of a socialist economy where social ownership displaces private ownership and thus class distinctions on the basis of private property ownership are eliminated, the modern state would have no function and would gradually "wither away" or be transformed into a new form of governance.[51][52]

Influenced by the pre-Marxist utopian socialist philosopher Henri de Saint-Simon, Friedrich Engels theorized the nature of the state would change during the transition to socialism. Both Saint-Simon and Engels described a transformation of the state from an entity primarily concerned with political rule over people (via coercion and law creation) to a scientific "administration of things" that would be concerned with directing processes of production in a socialist society, essentially ceasing to be a state.[53][54][55] Although Marx never referred to a socialist state, he argued that the working class would have to take control of the state apparatus and machinery of government in order to transition out of capitalism and to socialism. The dictatorship of the proletariat would represent this transitional state and would involve working class interests dominating government policy in the same manner that capitalist class interests dominate government policy under capitalism (the dictatorship of the bourgeoisie). Engels argued that as socialism developed, the state would change in form and function. Under socialism, it is not a "government of people, but the administration of things", thereby ceasing to be a state by the traditional definition.[56][57] With the fall of the Paris Commune, Marx cautiously argued in The Civil War in France that "the working class cannot simply lay hold of the ready-made state machinery, and wield it for its own purposes. The centralized state power, with its ubiquitous organs of standing army, police, bureaucracy, clergy, and judicature—organs wrought after the plan of a systematic and hierarchic division of labor originates from the days of absolute monarchy, serving nascent middle class society as a mighty weapon in its struggle against feudalism".[58] In other words, "the centralized state power inherited by the bourgeoisie from the absolute monarchy necessarily assumes, in the course of the intensifying struggles between capital and labor, 'more and more the character of the national power of capital over labour, of a public organized for social enslavement, of an engine of class despotism'".[59]

One of the most influential modern visions of a transitional state representing proletarian interests was based on the Paris Commune in which the workers and working poor took control of the city of Paris in 1871 in reaction to the Franco-Prussian War. Marx described the Paris Commune as the prototype for a revolutionary government of the future, "the form at last discovered" for the emancipation of the proletariat.[58] Engels noted that "all officials, high or low, were paid only the wages received by other workers. [...] In this way an effective barrier to place-hunting and careerism was set up".[60] Commenting on the nature of the state, Engels continued: "From the outset the Commune was compelled to recognize that the working class, once come to power, could not manage with the old state machine". In order not to be overthrown once having conquered power, Engels argues that the working class "must, on the one hand, do away with all the old repressive machinery previously used against it itself, and, on the other, safeguard itself against its own deputies and officials, by declaring them all, without exception, subject to recall at any moment". Engels argued such a state would be a temporary affair and suggested a new generation brought up in "new and free social conditions" will be able to "throw the entire lumber of the state on the scrap-heap".[61]

Reform and revolution

Socialists that embraced reformism, exemplified by Eduard Bernstein, took the view that both socialism and a socialist state will gradually evolve out of political reforms won in the organized socialist political parties and unions. These views are considered a revision of Marxist thought. Bernstein stated: "The socialist movement is everything to me while what people commonly call the goal of Socialism is nothing".[62] Following Marx, revolutionary socialists instead take the view that the working class grows stronger through its battle for reforms (such as in Marx's time the ten-hours bill). In 1848, Marx and Engels wrote:

Now and then the workers are victorious, but only for a time. The real fruit of their battles lies, not in the immediate result, but in the ever expanding union of the workers. [...] [I]t ever rises up again, stronger, firmer, mightier. It compels legislative recognition of particular interests of the workers, by taking advantage of the divisions among the bourgeoisie itself. Thus, the ten-hours' bill in England was carried.[63]

According to the orthodox Marxist conception, these battles eventually reach a point where a revolutionary movement arises. A revolutionary movement is required in the view of Marxists to sweep away the capitalist state and the dictatorship of the bourgeoisie which must be abolished and replaced with a dictatorship of the proletariat to begin constructing a socialist society. In this view, only through revolution can a socialist state be established as written in The Communist Manifesto:

In depicting the most general phases of the development of the proletariat, we traced the more or less veiled civil war, raging within existing society, up to the point where that war breaks out into open revolution, and where the violent overthrow of the bourgeoisie lays the foundation for the sway of the proletariat.[63]

Other historic reformist or gradualist movements within socialism, as opposed to revolutionary approaches, include Fabian socialist and Menshevik groupings.

2.2. Leninist Theory of the State

Whereas Marx, Engels and classical Marxist thinkers had little to say about the organization of the state in a socialist society, presuming the modern state to be specific to the capitalist mode of production, Vladimir Lenin pioneered the idea of a revolutionary state based on his theory of the revolutionary vanguard party and organizational principles of democratic centralism. Adapted to the conditions of semi-feudal Russia, Lenin's concept of the dictatorship of the proletariat involved a revolutionary vanguard party acting as representatives of the proletariat and its interests. According to Lenin's April Theses, the goal of the revolution and vanguard party is not the introduction of socialism (it could only be established on a worldwide scale), but to bring production and the state under the control of the soviets of workers' deputies. Following the October Revolution in Russia, the Bolsheviks consolidated their power and sought to control and direct the social and economic affairs of the state and broader Russian society to safeguard against counterrevolutionary insurrection, foreign invasion and to promote socialist consciousness among the Russian population while simultaneously promoting economic development.[64]

These ideas were adopted by Lenin in 1917 just prior to the October Revolution in Russia and published in The State and Revolution. With the failure of the worldwide revolution, or at least European revolution, envisaged by Lenin and Leon Trotsky, the Russian Civil War and finally Lenin's death, war measures that were deemed to be temporary such as forced requisition of food and the lack of democratic control became permanent and a tool to boost Joseph Stalin 's power, leading to the emergence of Marxism–Leninism and Stalinism as well as the notion that socialism can be created and exist in a single state with theory of socialism in one country.

Lenin argued that as socialism is replaced by communism, the state would "wither away"[65] as strong centralized control progressively reduces as local communities gain more empowerment. As he put succinctly, "[s]o long as the state exists there is no freedom. When there will be freedom, there will be no state".[66] In this way, Lenin was thereby proposing a classically dynamic view of progressive social structure which during his own short period of governance emerged as a defensive and preliminary bureaucratic centralist stage. He regarded this structural paradox as the necessary preparation for and antithesis of the desired workers' state which he forecast would follow.

2.3. Trotskyist Theory of the State

Following Stalin's consolidation of power in the Soviet Union and static centralization of political power, Trotsky condemned the Soviet government's policies for lacking widespread democratic participation on the part of the population and for suppressing workers' self-management and democratic participation in the management of the economy. Because these authoritarian political measures were inconsistent with the organizational precepts of socialism, Trotsky characterized the Soviet Union as a deformed workers' state that would not be able to effectively transition to socialism. Ostensibly socialist states where democracy is lacking, yet the economy is largely in the hands of the state, are termed by orthodox Trotskyist theories as degenerated or deformed workers' states and not socialist states.[67]

3. Controversy

3.1. Anarchism and Marxism

Many democratic and libertarian socialists, including anarchists, mutualists and syndicalists, criticize the concept of establishing a socialist state instead of abolishing the bourgeois state apparatus outright. They use the term state socialism to contrast it with their own form of socialism which involves either collective ownership (in the form of worker cooperatives) or common ownership of the means of production without state centralized planning. Those socialists believe there is no need for a state in a socialist system because there would be no class to suppress and no need for an institution based on coercion and therefore regard the state being a remnant of capitalism.[68][69][70] They hold that statism is antithetical to true socialism,[71] the goal of which is the eyes of libertarian socialists such as William Morris, who wrote as follows in a Commonweal article: "State Socialism? — I don't agree with it; in fact I think the two words contradict one another, and that it is the business of Socialism to destroy the State and put Free Society in its place".[72]

Classical and orthodox Marxists also view state socialism as an oxymoron, arguing that while an association for managing production and economic affairs would exist in socialism, it would no longer be a state in the Marxist definition which is based on domination by one class. Preceding the Bolshevik-led revolution in Russia, many socialist groups—including reformists, orthodox Marxist currents such as council communism and the Mensheviks as well as anarchists and other libertarian socialists—criticized the idea of using the state to conduct planning and nationalization of the means of production as a way to establish socialism.[73] Lenin himself acknowledged his policies as state capitalism.[74][75][76][77]

Critical of the economy and government of socialist states, left communists such as the Italian Amadeo Bordiga said that their socialism was a form of political opportunism which preserved rather than destroyed capitalism because of the claim that the exchange of commodities would occur under socialism; the use of popular front organisations by the Communist International;[78] and that a political vanguard organized by organic centralism was more effective than a vanguard organized by democratic centralism.[79] The American Marxist Raya Dunayevskaya also dismissed it as a type of state capitalism[80] because state ownership of the means of production is a form of state capitalism;[81] the dictatorship of the proletariat is a form of democracy and single-party rule is undemocratic;[82] and Marxism–Leninism is neither Marxism nor Leninism, but rather a composite ideology which socialist leaders like Joseph Stalin used to expediently determine what is communism and what is not communism among the Eastern Bloc countries.[83]

3.2. Leninism

Although most Marxist–Leninists distinguish between communism and socialism, Bordiga, who did consider himself a Leninist and has been described as being "more Leninist than Lenin",[84] did not distinguish between the two in the same way Marxist–Leninists do. Both Lenin and Bordiga did not see socialism as a separate mode of production from communism, but rather just as how communism looks as it emerges out of capitalism before it has "developed on its own foundations".[85]

This is coherent with Marx and Engels, who used the terms communism and socialism interchangeably.[86][87] Like Lenin, Bordiga used socialism to mean what Marx called the lower-phase communism.[88] For Bordiga, both stages of socialist or communist society—with stages referring to historical materialism—were characterized by the gradual absence of money, the market and so on, the difference between them being that earlier in the first stage a system of rationing would be used to allocate goods to people while in communism this could be abandoned in favour of full free access. This view distinguished Bordiga from Marxist–Leninists, who tended and still tend to telescope the first two stages and so have money and the other exchange categories surviving into socialism, but Bordiga would have none of this. For him, no society in which money, buying and selling and the rest survived could be regarded as either socialist or communist—these exchange categories would die out before the socialist rather than the communist stage was reached.[78] Stalin made the claim that the Soviet Union had reached the lower stage of communism and argued that the law of value still operated within a socialist economy.[89]

Marx did not use the term socialism to refer to this development and instead called it a communist society that has not yet reached its higher-stage.[90] The term socialism to mean the lower-state of communism was popularized during the Russian Revolution by Lenin. This view is consistent with and helped to inform early concepts of socialism in which the law of value no longer directs economic activity, namely that monetary relations in the form of exchange-value, profit, interest and wage labour would not operate and apply to Marxist socialism.[91] Unlike Stalin, who first claimed to have achieved socialism with the Soviet Constitution of 1936[92][93][94][95] and then confirmed it in the Economic Problems of Socialism in the USSR,[96][97][98][99][100] Lenin did not call the Soviet Union a socialist state, nor did he claim that it had achieved socialism.[101] He adopted state capitalist policies,[102][103][104][105] defending them from left-wing criticism,[106] but arguing that they were necessary for the future development of socialism and not socialist in themselves.[107][108] On seeing the Soviet Union's growing coercive power, Lenin was quoted as saying that Russia had reverted to "a bourgeois tsarist machine [...] barely varnished with socialism".[109]

A variety of non-state, libertarian communist and socialist positions reject the concept of a socialist state altogether, believing that the modern state is a byproduct of capitalism and cannot be used for the establishment of a socialist system. They reason that a socialist state is antithetical to socialism and that socialism will emerge spontaneously from the grassroots level in an evolutionary manner, developing its own unique political and economic institutions for a highly organized stateless society. Libertarian communists, including anarchists, councillists, leftists and Marxists, also reject the concept of a socialist state for being antithetical to socialism, but they believe that socialism can only be established through revolution and dissolving the existence of the state.[69][70][71] Within the socialist movement, there is criticism towards the use of the term socialist states in relation to countries such as China and previously of Soviet Union and Eastern and Central European states before what some term the "collapse of Stalinism" in 1989.[110][111][112][113]

Anti-authoritarian communists and socialists such as anarchists, other democratic and libertarian socialists as well as revolutionary syndicalists and left communists[114] claim that the so-called socialist states actually presided over state capitalist economies and cannot be called socialist.[80] Those socialists who oppose any system of state control whatsoever believe in a more decentralized approach which puts the means of production directly into the hands of the workers rather than indirectly through state bureaucracies[69][70][71] which they claim represent a new elite or class.[115][116][117][118] This leads them to consider state socialism a form of state capitalism[78] (an economy based on centralized management, capital accumulation and wage labor, but with the state owning the means of production)[119] which Engels stated would be the final form of capitalism rather than socialism.[120]

3.4. Trotskyism

Some Trotskyists following on from Tony Cliff deny that it is socialism, calling it state capitalism.[121] Other Trotskyists agree that these states could not be described as socialist,[122] but deny that they were state capitalist.[123] They support Leon Trotsky's analysis of pre-restoration Soviet Union as a workers' state that had degenerated into a bureaucratic dictatorship which rested on a largely nationalized industry run according to a production plan[124][125][126] and claimed that the former Stalinist states of Central and Eastern Europe were deformed workers' states based on the same relations of production as the Soviet Union.[127] Some Trotskyists such as the Committee for a Workers' International have at times included African, Asian and Middle Eastern socialist states when they have had a nationalized economy as deformed workers' states.[128][129] Other socialists argued that the neo-Ba'athists promoted capitalists from within the party and outside their countries.[130]

4.2. Current

| Country | System | Beginning | Party | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| China | Popular Republic | 1949 | Communist Party of China | With free market reforms progressively implemented from the government of Deng Xiaoping, up to the current socialism with Chinese characteristics. |

| North Korea | Democratic People's Republic | 1948 | Workers' Party of Korea | The official ideology of the state is Juche, started as a national adaptation of Marxism-Leninism but independent of it. In 2009 the word "communism" was removed from the constitution, replacing it with "socialism". |

| Cuba | Socialist Republic | 1961 | Communist Party of Cuba | Initially with a political-economic system one-party and statist. After the fall of the Soviet Union and with the end of CAME, Cuba progressively adopted some market reforms to allow private property in certain sectors. |

| Laos | Democratic People's Republic | 1975 | Lao People's Revolutionary Party | With the market gradually liberalized since the adoption of a new economic mechanism |

| Vietnam | Socialist Republic | 1976 | Communist Party of Vietnam | From the economic opening known as Doi Moi, Vietnam practices the so-called market economy oriented to socialism. |

4.3. Historical

| Country | System | Beginning | End | Party | Leaders |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afghanistan | Democratic Republic | 1978 | 1992 | People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan (Khalq) | Nur Mohammad Taraki 1978–79 Hafizullah Amin 1979 Babrak Karmal 1979–86 Mohammad Najibullah 1986–92 |

| Albania | Democratic Republic and People's Republic | 1944 | 1992 | Party of Labour of Albania | Enver Hoxha 1944–85 Ramiz Alia 1985–91 |

| Angola | People's Republic | 1975 | 1992 | MPLA | Agostinho Neto 1975–79 José Eduardo dos Santos 1979–92 |

| East Germany | Democratic Republic | 1949 | 1990 | Socialist Unity Party of Germany | Wilhelm Pieck 1946–50 Walter Ulbricht 1950–1971 Erich Honecker 1971–1989 |

| Benin | People's Republic | 1975 | 1990 | People's Revolutionary Party of Benin | Mathieu Kérékou 1975–90 |

| Bulgaria | People's Republic | 1946 | 1990 | Bulgarian Communist Party | Georgi Dimitrov 1946–49 Valko Chervenkov 1949–54 Todor Zhivkov 1954–89 Petar Mladenov 1989–90 |

| Czechoslovakia | Federal Socialist Republic | 1948 | 1989 | Communist Party of Czechoslovakia | Klement Gottwald 1948–53 Antonín Novotný 1953–68 Alexander Dubček 1968–69 Gustav Husak 1969–87 Miloš Jakeš 1987–89 Karel Urbánek 1989 |

| Chile | Socialist Republic | 1932 | 1932 | Socialist Party of Chile | Arturo Puga Osorio 1932 Carlos Dávila 1932 |

| Congo-Brazzaville | People's Republic | 1970 | 1991 | Congolese Party of Labour | Marien Ngouabi 1970–77 Military Committee of the CPL 1977–91 |

| Ethiopia | Provisional Military Government | 1974 | 1987 | Military Junta | Mengistu Haile Mariam 1974–1987 |

| Ethiopia | People's Democratic Republic | 1987 | 1991 | Workers' Party of Ethiopia | Mengistu Haile Mariam 1987–91 |

| Grenada | Socialist state | 1979 | 1983 | New Jewel Movement | Maurice Bishop 1979–83 Bernard Coard 1983 Hudson Austin 1983 |

| Hungary | People's Republic | 1949 | 1989 | Hungarian Working People's Party | Mátyás Rákosi 1948–56 Ernő Gerő 1956 János Kádár 1956–88 Károly Grósz 1988–89 |

| Kampuchea | Democratic Republic | 1975 | 1979 | Communist Party of Kampuchea (Khmer Rouge) | Pol Pot 1975–79 |

| Kampuchea (1979-1989) Cambodia (1989-1991) |

People’s Republic (1979-1989) Republic (1989-1991) |

1979 | 1991 | Kampuchean People's Revolutionary Party (1979-1989) Cambodian People’s Party (1989-1991) |

Pen Sovan 1979–81 Heng Samrin 1981–91 |

| Mongolia | People's Republic | 1924 | 1992 | Mongolian People's Party | Navaandorjiyn Jadambaa(primero) 1924 Punsalmaagiin Ochirbat(último) 1990–92 |

| Mozambique | People's Republic | 1975 | 1990 | FRELIMO | Samora Machel 1975–86 Political Bureau 1986 Joaquim Chissano 1986–90 |

| Poland | People's Republic | 1945 | 1989 | Polish United Workers' Party | Bolesław Bierut 1948–56 Edward Ochab 1956 Władysław Gomułka 1956–70 Edward Gierek 1970–80 Stanisław Kania 1980–81 Wojciech Jaruzelski 1981–89 Mieczysław Rakowski 1989–90 |

| Romania | Popular Republic (since 1965 Socialist Republic) | 1947 | 1989 | Romanian Communist Party | G. Gheorghiu-Dej 1947–65 Nicolae Ceauşescu 1965–89 |

| Somalia | Democratic Republic | 1969 | 1991 | Somali Revolutionary Socialist Party | Mohamed Siad Barre 1969–91 |

| Soviet Union | Federation of Socialist Republics | 1922 | 1991 | Communist Party of the Soviet Union | Vladimir Lenin 1917–24 Joseph Stalin 1922–52 Nikita Khrushchev 1953–64 Leonid Brezhnev 1964–82 Yuri Andropov 1982–84 Konstantin Chernenko 1984–85 Mikhail Gorbachev 1985–91 |

| North Vietnam | Democratic Republic | 1945 | 1976 | Workers' Party of Vietnam | Hô Chí Minh 1945–69 Tôn Đức Thắng 1969–76 |

| South Yemen | People's Democratic Republic | 1967 | 1990 | Yemeni Socialist Party | Abdul Fattah Ismail 1967–80 Ali Nasir Muhammad 1980–86 Ali Salem al Beidh 1986–90 |

| Yugoslavia | Socialist Federal Republic | 1945 | 1992 | League of Communists of Yugoslavia | Josip Broz Tito 1945–80 |

4.4. Absorbed by the USSR

| Country | Beginning | End | Party | Leader |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Finland | 1939 | 1940 | Communist Party of Finland | Otto Kuusinen 1939–40 |

| Tannu Tuva | 1921 | 1944 | Tuvan People's Revolutionary Party | Salchak Toka 1921–44 |

| Country | Beginning | End | Leaders |

|---|---|---|---|

| Algeria | 1963 | 1989 | Ahmed Ben Bella 1963–65 Houari Boumédiène 1965–78 Rabah Bitat 1978–79 Chadli Bendjedid 1979–89 |

| Burma | 1974 | 1988 | Ne Win 1974–88 |

| Cape Verde | 1975 | 1991 | Aristides Pereira 1975–91 |

| Ghana | 1960 | 1966 | Kwame Nkrumah 1960–66 |

| Iraq | 1968 | 2003 | Ahmed Hasan al-Bakr 1968–79 Saddam Hussein 1979–2003 |

| Libya | 1977 | 2011 | Muammar Gadafi 1977–2011 |

| Madagascar | 1975 | 1993 | Didier Ratsiraka 1975–93 |

| Seychelles | 1977 | 1992 | France-Albert René 1977–92 |

| Syria | 1963 | 2012 | Amin al-Hafiz 1963–66 Nureddin al-Atassi 1966–70 Ahmad al-Khatib 1970–71 Hafez al-Asad 1971–2000 Bashar al-Asad 2000–12 |

4.6. Ephemeral

| Country | Year | Leaders |

|---|---|---|

| Bavaria (People's State) | 1918–1919 | Kurt Eisner 1918–1919 Johannes Hoffman 1919 |

| Bavaria (Soviet Republic) | 1919 | Ernst Toller 1919 Eugen Leviné 1919 |

| Gilan | 1920–1921 | Mirza Koochak Khan 1920–21 |

| Hungary | 1919 | Sándor Garbai / Béla Kun (de facto) 1919 |

| Paris (France) | 1871 | Louis Charles Delescluze 1871 |

| Slovakia | 1919 | Antonín Janoušek 1919 |

| South Vietnam | 1975–1976 | Nguyễn Hữu Thọ 1975–76 |

References

- Jones, R. J. Barry (2002). Routledge Encyclopedia of International Political Economy, Volume 3. Routledge. p. 1461. ISBN 9781136927393. https://books.google.com/books?id=ouZJAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA1461.

- Furtak, Robert K. (1986). Political Systems of the Socialist States: An Introduction to Marxist-Leninist Regimes. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN:978-0745000480.

- Tompson, William J. (1997). Khrushchev: A Political Life. New York City: St. Martin's Press. p. 238.

- Morgan, W. John (2001). "Marxism–Leninism: The Ideology of Twentieth-Century Communism". In Wright, James D., ed. International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences (2nd ed.). Oxford: Elsevier. pp. 657–662.

- Andrai, Charles F. (1994). Comparative Political Systems: Policy Performance and Social Change. Armonk, New York: M. E. Sharpe. pp. 24–25.

- "Juche is Third Position ideology built on Marx – Not Marxist-Leninism". Free Media Productions – Editorials. 30 August 2009. http://www.freemediaproductions.info/Editorials/2009/08/30/juche-is-third-position-ideology-built-on-marx-not-marxist-leninism/.

- "VN Embassy – Constitution of 1992". From the Preamble: "On 2 July 1976, the National Assembly of reunified Vietnam decided to change the country's name to the Socialist Republic of Vietnam; the country entered a period of transition to socialism, strove for national construction, and unyieldingly defended its frontiers while fulfilling its internationalist duty." http://www.vietnamembassy-usa.org/learn_about_vietnam/politics/constitution/

- "Constitution of the Republic of Cuba, 1992". Cubanet. From Article 5: "The Communist Party of Cuba, a follower of Martí's ideas and of Marxism–Leninism, and the organized vanguard of the Cuban nation, is the highest leading force of society and of the state, which organizes and guides the common effort toward the goals of the construction of socialism and the progress toward a communist society". http://www.cubanet.org/ref/dis/const_92_e.htm

- Reuters (22 July 2018). "Cuba ditches aim of building communism from draft constitution". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 August 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/jul/22/cuba-ditches-aim-of-building-communism-from-draft-constitution

- The "Preamble to the 1976 Constitution of Portugal" stated: "The Constituent Assembly affirms the Portuguese people's decision to defend their national independence, safeguard the fundamental rights of citizens, establish the basic principles of democracy, secure the primacy of the rule of law in a democratic state, and open the way to socialist society." http://www.servat.unibe.ch/icl/po00000_.html

- Tschentscher, Axel. "Croatia Constitution". http://www.servat.unibe.ch/icl/hr00000_.html.

- Tschentscher, Axel. "Hungary Index". http://www.servat.unibe.ch/icl/hu__indx.html.

- Tschentscher, Axel. "Poland – Constitution". http://www.servat.unibe.ch/icl/pl00000_.html.

- The Preamble of the Constitution of India reads: "We, the people of India, having solemnly resolved to constitute India into a sovereign, socialist, secular, democratic, republic [...]". See Preamble to the Constitution of India.

- Wall, Derek (25 August 2014). "Rojava: a beacon of hope fighting Isis". Morning Star. http://www.morningstaronline.co.uk/a-fe30-Rojava-a-beacon-of-hope-fighting-Isis.

- Barrett, William, ed. (1 April 1978). "Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy: A Symposium". Commentary. Retrieved 14 June 2020. "If we were to extend the definition of socialism to include Labor Britain or socialist Sweden, there would be no difficulty in refuting the connection between capitalism and democracy." https://www.commentarymagazine.com/articles/capitalism-socialism-and-democracy/

- Heilbroner, Robert L. (Winter 1991). "From Sweden to Socialism: A Small Symposium on Big Questions". Dissident. Barkan, Joanne; Brand, Horst; Cohen, Mitchell; Coser, Lewis; Denitch, Bogdan; Fehèr, Ferenc; Heller, Agnès; Horvat, Branko; Tyler, Gus. pp. 96–110. Retrieved 17 April 2020. https://www.dissentmagazine.org/article/from-sweden-to-socialism-social-democracy-symposium

- Kendall, Diana (2011). Sociology in Our Time: The Essentials. Cengage Learning. pp. 125–127. ISBN:9781111305505. "Sweden, Great Britain, and France have mixed economies, sometimes referred to as democratic socialism—an economic and political system that combines private ownership of some of the means of production, governmental distribution of some essential goods and services, and free elections. For example, government ownership in Sweden is limited primarily to railroads, mineral resources, a public bank, and liquor and tobacco operations."

- Li, He (2015). Political Thought and China's Transformation: Ideas Shaping Reform in Post-Mao China. Springer. pp. 60–69. ISBN:9781137427816. "The scholars in camp of democratic socialism believe that China should draw on the Sweden experience, which is suitable not only for the West but also for China. In the post-Mao China, the Chinese intellectuals are confronted with a variety of models. The liberals favor the American model and share the view that the Soviet model has become archaic and should be totally abandoned. Meanwhile, democratic socialism in Sweden provided an alternative model. Its sustained economic development and extensive welfare programs fascinated many. Numerous scholars within the democratic socialist camp argue that China should model itself politically and economically on Sweden, which is viewed as more genuinely socialist than China. There is a growing consensus among them that in the Nordic countries the welfare state has been extraordinarily successful in eliminating poverty."

- "The Managerial Society Part Three — Fabian Version". Socialist Standard (Socialist Party of Great Britain) (641). January 1958. http://www.worldsocialism.org/spgb/socialist-standard/1950s/1958/no-641-january-1958/managerial-society-part-three-—-fabian-version. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- Crosland, Anthony (2006) [1952]. The Future of Socialism. Constable. pp. 9, 89. ISBN:978-1845294854.

- Bevan, Aneurin (1952). In Place of Fear. New York: Simon and Schuster. p. 106.

- Batson, Andrew (March 2017). "The State of the State Sector". Gavekal Dragonomics. http://www.cebc.org.br/sites/default/files/the_state_of_the_state_sector.pdf. "Even in the statist 1960s–70s, SOEs in France and the UK did not account for more than 15–20% of capital formation; in the 1980s the developed-nation average was around 8%, and it dropped below 5% in the 1990s."

- Cobham, David (November 1984). "The Nationalisation of the Banks in Mitterand's France: Rationalisations and Reasons". Journal of Public Policy. 4 (4). JSTOR 3998375. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3998375

- Cohen, Paul (Winter 2010). "Lessons from the Nationalization Nation: State-Owned Enterprises in France". Dissident. Retrieved 17 April 2020. https://www.dissentmagazine.org/article/lessons-from-the-nationalization-nation-state-owned-enterprises-in-france

- Morley, James W. (1993). Driven by Growth: Political Change in the Asia-Pacific Region. Armonk, New York: M. E. Sharpe.

- Kerr, Roger (9 December 1999). "Optimism for the New Millennium". Rotary Club of Wellington North. http://www.nzbr.org.nz/documents/speeches/speeches-99/optimism_for_the_new-millennium.doc.htm.

- Åslund, Anders (2009). How Ukraine Became a Market Economy and Democracy. Peterson Institute. p. 12. ISBN 9780881325461. https://books.google.com/books?id=C8C3xuqd6aMC.

- Minahan, James (2013). Miniature Empires: A Historical Dictionary of the Newly Independent States. Routledge. p. 296. ISBN 9781135940102. https://books.google.com/books?id=jwNeAgAAQBAJ.

- Tunçer-Kılavuz, Idil (2014). Power, Networks and Violent Conflict in Central Asia: A Comparison of Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. Routledge advances in Central Asian studies. Volume 5. Routledge. p. 53. ISBN 9781317805113. https://books.google.com/books?id=vv7pAwAAQBAJ.

- Khabtagaeva, Bayarma (2009). Mongolic Elements in Tuvan. Turcologica Series. Volume 81. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 21. ISBN 9783447060950. https://books.google.com/books?id=zddhapKVdHMC.

- Macdonald, Fiona; Stacey, Gillian; Steele, Philip (2004). Peoples of Eastern Asia. Volume 8: Mongolia–Nepal. Marshall Cavendish. p. 413. ISBN 9780761475477. https://books.google.com/books?id=QXWjAmmZ5kMC.

- Gjevori, Elvin (2018). Democratisation and Institutional Reform in Albania. Springer. p. 21. ISBN 9783319730714. https://books.google.com/books?id=l5FODwAAQBAJ.

- Stankova, Marietta (2014). Bulgaria in British Foreign Policy, 1943–1949. Anthem Series on Russian, East European and Eurasian Studies. Anthem Press. p. 148. ISBN 9781783082353. https://books.google.com/books?id=iCw2DgAAQBAJ.

- Müller-Rommel, Ferdinand; Mansfeldová, Zdenka (2001). "Chapter 5: Czech Republic". Cabinets in Eastern Europe. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 62. doi:10.1057/9781403905215_6. ISBN 978-1-349-41148-1. https://dx.doi.org/10.1057%2F9781403905215_6

- Hajdú, József (2011). Labour Law in Hungary. Kluwer Law International. p. 27. ISBN 9789041137920. https://books.google.com/books?id=L1Ra6WYtqsgC.

- Frankowski, Stanisław; Stephan, Paul B. (1995). Legal Reform in Post-Communist Europe: The View from Within. Martinus Nijhoff. p. 23. ISBN 9780792332183. https://books.google.com/books?id=LAiYFR0MPXgC.

- Paquette, Laure (2001). NATO and Eastern Europe After 2000: Strategic Interactions with Poland, the Czech Republic, Romania, and Bulgaria. Nova. p. 55. ISBN 9781560729693. https://books.google.com/books?id=PE_D8ZewHKQC.

- Lampe, John R. (2000). Yugoslavia as History: Twice There Was a Country. Cambridge University Press. p. 233. ISBN 9780521774017. https://books.google.com/books?id=AZ1x7gvwx_8C.

- "The Chinese Revolution of 1949". United States Department of State. https://history.state.gov/milestones/1945-1952/chinese-rev.

- Kihl, Young Whan; Kim, Hong Nack (2014). North Korea: The Politics of Regime Survival. Routledge. p. 8. ISBN 9781317463764. https://books.google.com/books?id=-EHfBQAAQBAJ.

- Webb, Adrian (2008). The Routledge Companion to Central and Eastern Europe Since 1919. Routledge Companions to History. Routledge. pp. 80, 88. ISBN 9781134065219. https://books.google.com/books?id=vut9AgAAQBAJ.

- Da Graça, John V (2000). Heads of State and Government (2nd ed.). St. Martin's Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-1-56159-269-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=M0YfDgAAQBAJ.

- Lenin Collected Works. 27: 293. Quoted by Aufheben. . https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/cw/volume27.htm

- Atkins, C. J. (1 April 2009). "The Problem of Transition: Development, Socialism and Lenin's NEP". Political Affairs. Retrieved 30 July 2009. http://politicalaffairs.net/the-problem-of-transition-development-socialism-and-lenin-s-nep/

- Wilczynski, J. (2008). The Economics of Socialism after World War Two: 1945–1990. Aldine Transaction. pp. 21. ISBN 978-0202362281. "Contrary to Western usage, these countries describe themselves as 'Socialist' (not 'Communist'). The second stage (Marx's 'higher phase'), or 'Communism' is to be marked by an age of plenty, distribution according to needs (not work), the absence of money and the market mechanism, the disappearance of the last vestiges of capitalism and the ultimate 'whithering away' of the State."

- Steele, David Ramsay (September 1999). From Marx to Mises: Post Capitalist Society and the Challenge of Economic Calculation. Open Court. p. 45. ISBN 978-0875484495. "Among Western journalists the term 'Communist' came to refer exclusively to regimes and movements associated with the Communist International and its offspring: regimes which insisted that they were not communist but socialist, and movements which were barely communist in any sense at all."

- Rosser, Mariana V.; Rosser Jr., J. Barkley (23 July 2003). Comparative Economics in a Transforming World Economy. MIT Press. pp. 14. ISBN 978-0262182348. "Ironically, the ideological father of communism, Karl Marx, claimed that communism entailed the withering away of the state. The dictatorship of the proletariat was to be a strictly temporary phenomenon. Well aware of this, the Soviet Communists never claimed to have achieved communism, always labeling their own system socialist rather than communist and viewing their system as in transition to communism."

- Williams, Raymond (1983). "Socialism". Keywords: A vocabulary of culture and society, revised edition. Oxford University Press. p. 289. ISBN 978-0-19-520469-8. https://archive.org/details/keywordsvocabula00willrich/page/289. "The decisive distinction between socialist and communist, as in one sense these terms are now ordinarily used, came with the renaming, in 1918, of the Russian Social-Democratic Labour Party (Bolsheviks) as the All-Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks). From that time on, a distinction of socialist from communist, often with supporting definitions such as social democrat or democratic socialist, became widely current, although it is significant that all communist parties, in line with earlier usage, continued to describe themselves as socialist and dedicated to socialism."

- Nation, R. Craig (1992). Black Earth, Red Star: A History of Soviet Security Policy, 1917–1991. Cornell University Press. pp. 85–6. ISBN 978-0801480072. https://archive.org/details/blackearthredsta00nati. Retrieved 19 December 2014.

- Engels, Friedrich (1962). Institut für Marxismus-Leninismus bein ZK der SED. ed (in de). Die Marx-Engels-Gesamtausgabe. Karl Marx-Friedrich Engels: Welke. 20. Berlin: Dietz Verlag.

- Engels, Friedrich (1962). Institut für Marxismus-Leninismus bein ZK der SED. ed (in de). Die Marx-Engels-Gesamtausgabe. Karl Marx-Friedrich Engels: Welke. 21. Berlin: Dietz Verlag.

- Engels, Friedrich (1880). "The Development of Utopian Socialism". Socialism: Utopian and Scientific. Marxists.org. http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1880/soc-utop/ch01.htm. Retrieved 12 January 2016. "In 1816, he declares that politics is the science of production, and foretells the complete absorption of politics by economics. The knowledge that economic conditions are the basis of political institutions appears here only in embryo. Yet what is here already very plainly expressed is the idea of the future conversion of political rule over men into an administration of things and a direction of processes of production."

- "Henri de Saint-Simon". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 27 December 2019. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Henri-de-Saint-Simon

- "Socialism". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 27 December 2019. https://www.britannica.com/topic/socialism

- "Withering away of the state". In Scruton, Roger (2007). The Palgrave Macmillan Dictionary of Political Thought (3rd ed.). Palgrave Macmillan.

- "Withering Away of the State". In Kurian, George Thomas, ed. (2011). The Encyclopedia of Political Science. Washington, D.C.: CQ Press.

- Marx, Karl (1871). The Civil War in France. "The Paris Commune". Marxists Internet Archive. Retrieved 27 December 2019. https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1871/civil-war-france/ch05.htm

- Van Den Berg, Axel (2018) [1988]. The Immanent Utopia: From Marxism on the State to the State of Marxism. Transaction Publishers. p. 71. ISBN:9781412837330.

- Engels, Friedrich (1891). "On the 20th Anniversary of the Paris Commune". In Marx, Karl (1871). The Civil War in France. Marxists Internet Archive. Retrieved 8 February 2020. https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1871/civil-war-france/postscript.htm

- Engels, Friedrich (18 March 1891). "The Civil War in France (1891 Introduction)". Marxists Internert Archive. http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1871/civil-war-france/postscript.htm.

- Steger, Manfred (1996). Selected Writings Of Eduard Bernstein, 1920–1921. New Jersey: Humanities Press.

- Marx, Karl; Engels, Friedrich (1848). The Communist Manifesto. "Chapter I. Bourgeois and Proletarians". Marxists Internert Archive. Retrieved 30 December 2019. https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1848/communist-manifesto/ch01.htm

- Fleming, Richard Fleming (1989). "Lenin's Conception of Socialism: Learning from the early experiences of the world's first socialist revolution". Forward 9 (1). https://www.marxists.org/history/erol/ncm-7/lenin-socialism.htm. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- Lenin, Vladimir (1917). The State and Revolution. p. 70. cf. "Chapter V, The economic basis for the withering away of the state".

- Freeden, Michael; Sargent, Lyman Tower; Stears, Marc, eds. (15 August 2013). The Oxford Handbook of Political Ideologies. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 371. ISBN:9780199585977. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1478-9302.12087_13

- Trotsky, Leon (1935). "The Workers' State, Thermidor and Bonapartism". New International. 2 (4): 116–122. "Trotsky argues that the Soviet Union was, at that time, a "deformed workers' state" or degenerated workers' state, and not a socialist republic or state, because the "bureaucracy wrested the power from the hands of mass organizations," thereby necessitating only political revolution rather than a completely new social revolution, for workers' political control (i.e. state democracy) to be reclaimed. He argued that it remained, at base, a workers' state because the capitalists and landlords had been expropriated". Retrieved 27 December 2019. https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1935/02/ws-therm-bon.htm

- Schumpeter, Joseph (2008). Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy. Harper Perennial. p. 169. ISBN 978-0-06-156161-0. "But there are still others (concepts and institutions) which by virtue of their nature cannot stand transplantation and always carry the flavor of a particular institutional framework. It is extremely dangerous, in fact it amounts to a distortion of historical description, to use them beyond the social world or culture whose denizens they are. Now ownership or property – also, so I believe, taxation – are such denizens of the world of commercial society, exactly as knights and fiefs are denizens of the feudal world. But so is the state (a denizen of commercial society)."

- McKay, Iain, ed (2012). An Anarchist FAQ. II. Edinburgh: AK Press. ISBN 978-1-902593-90-6. OCLC 182529204. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/182529204

- McKay, Iain, ed (2012). An Anarchist FAQ. II. Edinburgh: AK Press. ISBN 978-1-902593-90-6. OCLC 182529204. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/182529204

- McKay, Iain, ed (2008). An Anarchist FAQ. I. Stirling: AK Press. ISBN 978-1-902593-90-6. OCLC 182529204. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/182529204

- William Morris (17 May 1890). "The 'Eight Hours' and the Demonstration". Commonweal. 6 (227). p. 153. Retrieved 4 November 2019. https://www.marxists.org/archive/morris/works/1890/commonweal/05-eight-hours.htm

- Screpanti, Ernesto; Zamagni, Stefano (2005). An Outline on the History of Economic Thought (2nd ed.). Oxford. p. 295. "It should not be forgotten, however, that in the period of the Second International, some of the reformist currents of Marxism, as well as some of the extreme left-wing ones, not to speak of the anarchist groups, had already criticised the view that State ownership and central planning is the best road to socialism. But with the victory of Leninism in Russia, all dissent was silenced, and socialism became identified with 'democratic centralism', 'central planning', and State ownership of the means of production."

- Lenin, Vladimir (1917). "Chapter 5". The State and Revolution. https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1917/staterev/ch05.htm#s4

- Lenin, Vladimir (February—July 1918). Lenin Collected Works Vol. 27. Marxists Internet Archive. p. 293. Quoted by Aufheben. . https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/cw/volume27.htm

- Lenin, Vladimir (1921). "The Tax in Kind". https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1921/apr/21.htm

- Pena, David S. (21 September 2007). "Tasks of Working-Class Governments under the Socialist-oriented Market Economy". Political Affairs. . http://www.politicalaffairs.net/article/articleview/5869/

- Bordiga, Amadeo (1952). "Dialogue With Stalin". Marxists Internet Archive. Retrieved 11 November 2019. https://www.marxists.org/archive/bordiga/works/1952/stalin.htm

- Bordiga, Amadeo. "Theses on the Role of the Communist Party in the Proletarian Revolution". Communist International. https://libcom.org/library/role_party_bordiga.

- Howard, M. C.; King, J. E. "State capitalism" in the Soviet Union". . http://www.hetsa.org.au/pdf/34-A-08.pdf

- Lichtenstein, Nelson (2011). American Capitalism: Social Thought and Political Economy in the Twentieth Century. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 160–161.

- Ishay, Micheline (2007). The Human Rights Reader: Major Political Essays, Speeches, and Documents from Ancient Times to the Present. Taylor & Francis. p. 245.

- Todd, Allan (2012). History for the IB Diploma: Communism in Crisis 1976–89. Cambridge University Press. p. 16. ASIN B01B997S8W. https://www.amazon.com/dp/B01B997S8W

- Piccone, Paul (1983). Italian Marxism. University of California Press. p. 134. https://books.google.com/books?id=HhYHyI9b13YC&pg=PA134&lpg=PA134&dq=Bordiga+more+Leninist+than+Lenin&source=bl&ots=NCHMPNBKY6&sig=ACfU3U3V2SEbKptCCM3U-Ax7Z6nFd96lxw&hl=it&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiysoDW-tTmAhWLRMAKHebND6sQ6AEwEnoECAoQAQ#v=onepage&q=Bordiga%20more%20Leninist%20than%20Lenin&f=false

- Lenin, Vladimir (1917). The State and Revolution. "Chapther 5". Marxists Internet Archive. Retrieved 27 December 2019. https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1917/staterev/ch05.htm

- Steele, David (1992). From Marx to Mises: Post-Capitalist Society and the Challenge of Economic Calculation. Open Court Publishing Company. pp. 44–45. ISBN 978-0-87548-449-5. "By 1888, the term 'socialism' was in general use among Marxists, who had dropped 'communism', now considered an old fashioned term meaning the same as 'socialism'. [...] At the turn of the century, Marxists called themselves socialists. [...] The definition of socialism and communism as successive stages was introduced into Marxist theory by Lenin in 1917 [...], the new distinction was helpful to Lenin in defending his party against the traditional Marxist criticism that Russia was too backward for a socialist revolution."

- Hudis, Peter; Vidal, Matt, Smith, Tony; Rotta, Tomás; Prew, Paul, eds. (September 2018 – June 2019). The Oxford Handbook of Karl Marx. "Marx's Concept of Socialism". Oxford University Press. ISBN:978-0190695545. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190695545.001.0001. https://www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190695545.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780190695545

- Marx, Karl (1875). Critique of the Gotha Program. "Part I". Marxists Internet Archive. Retrieved 8 February 2020. https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1875/gotha/ch01.htm

- Stalin, Joseph (1951). "Economic Problems of Socialism in the USSR". Marxists Internet Archive. Retrieved 27 December 2019. https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/stalin/works/1951/economic-problems/index.htm

- Marx, Karl (1875). "Part I". Critique of the Gotha Program. Marxists nternet Archive. Retrieved 27 December 2019. https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1875/gotha/ch01.htm

- Bockman, Johanna (2011). Markets in the name of Socialism: The Left-Wing origins of Neoliberalism. Stanford University Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-8047-7566-3. "According to nineteenth-century socialist views, socialism would function without capitalist economic categories, such as money, prices, interest, profits and rent. Rather, it would function according to laws other than those described by current economic science. While some socialists recognized the need for money and prices (at least during the transition from capitalism to socialism), socialists more commonly believed that the socialist economy would soon administratively mobilize the economy in physical units without the use of prices or money."

- Reinalda, Bob (2009). Routledge History of International Organizations: From 1815 to the Present Day. Routledge. p. 765. ISBN 9781134024056.

- Laidler, Harry W. (2013). History of Socialism: An Historical Comparative Study of Socialism, Communism, Utopia. Routledge. p. 412. ISBN 9781136231438.

- Smith, S. A. (2014). The Oxford Handbook of the History of Communism. Oxford University Press. p. 126. ISBN 9780191667527. "The 1936 Constitution described the Soviet Union for the first time as a 'socialist society', rhetorically fulfilling the aim of building socialism in one country, as Stalin had promised."

- Socialist Law in Socialist East Asia. Cambridge University Press. 2018. p. 58. ISBN 9781108424813.

- Ramana, R. (June 1983). "Reviewed Work: China's Socialist Economy by Xue Muqiao". Social Scientist 11 (6): 68–74. doi:10.2307/3516910. https://dx.doi.org/10.2307%2F3516910

- McCarthy, Greg (1985). Brugger, Bill. ed. Chinese Marxism in Flux, 1978–1984: Essays on Epistemology, Ideology, and Political Economy. M. E. Sharpe. pp. 142–143. ISBN 0873323238.

- Evans, Alfred B. (1993). Soviet Marxism–Leninism: The Decline of an Ideology. ABC-CLIO. p. 48. ISBN 9780275947637.

- Pollock, Ethan (2006). Stalin and the Soviet Science Wars. Princeton University Press. p. 210. ISBN 9780691124674.

- Mommen, André (2011). Stalin's Economist: The Economic Contributions of Jenö Varga. Routledge. pp. 203–213. ISBN 9781136793455.

- Lenin, Vladimir (21 April 1921). "The Tax in Kind". Marxists Internet Archive. Retrieved 10 February 2020. "No one, I think, in studying the question of the economic system of Russia, has denied its transitional character. Nor, I think, has any Communist denied that the term Soviet Socialist Republic implies the determination of the Soviet power to achieve the transition to socialism, and not that the existing economic system is recognised as a socialist order." https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1921/apr/21.htm

- Lenin, Vladimir (1917). The State and Revolution. "Chapter 5". Marxists Internet Archive. Retrieved 8 February 2020. https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1917/staterev/ch05.htm#s4

- Lenin, Vladimir (February—July 1918). Lenin Collected Works Vol. 27. Marxists Internet Archive. p. 293. Quoted by Aufheben. . https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/cw/volume27.htm

- Lenin, Vladimir (1921). "The Tax in Kind". Marxists Internet Archive. Retrieved 8 February 2020. https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1921/apr/21.htm

- Pena, David S. (21 September 2007). "Tasks of Working-Class Governments under the Socialist-oriented Market Economy". Political Affairs. . Retrieved 8 February 2020. http://www.politicalaffairs.net/article/articleview/5869/

- Lenin, Vladimir (June 1920). "Left-Wing" Communism: An Infantile Disorder. "Contents". Marxists Internet Archive. Retrieved 10 February 2020. https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1920/lwc/index.htm

- Lenin, Vladimir (29 April 1918). "Session of the All-Russia C.E.C." Marxists Internet Archive. Retrieved 10 February 2020. " Reality tells us that state capitalism would be a step forward. If in a small space of time we could achieve state capitalism in Russia, that would be a victory." https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1918/apr/29.htm

- Lenin, Vladimir (21 April 1921). "The Tax in Kind". Marxists Internet Archive. Retrieved 10 February 2020. "State capitalism would be a step forward as compared with the present state of affairs in our Soviet Republic. If in approximately six months' time state capitalism became established in our Republic, this would be a great success and a sure guarantee that within a year socialism will have gained a permanently firm hold and will have become invincible in this country." https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1921/apr/21.htm

- Serge, Victor (1937). From Lenin to Stalin. New York: Pioneer Publishers. p. 55. https://www.marxists.org/archive/serge/1937/FromLeninToStalin-BW-T144.pdf

- Committee for a Workers' International (June 1992). "The Collapse of Stalinism". Marxist.net. Retrieved 4 November 2019. http://www.marxist.net/stalinism/

- Ted Grant (1996). "The Collapse of Stalinism and the Class Nature of the Russian State". Retrieved 4 November 2019. https://www.marxists.org/archive/grant/1996/02/collapse.htm

- Anthony Arnove (Winter 2000). "The Fall of Stalinism: Ten Years On". International Socialist Review. 10. Retrieved 4 November 2019. http://www.isreview.org/issues/10/TheFallOfStalinism.shtml

- Walter Daum (Fall 2002). "Theories of Stalinism's Collapse". Proletarian Revolution. 65. Retrieved 4 November 2019. https://www.marxists.org/history/etol/newspape/socialistvoice/StalinismPR65.html

- "4. State Capitalism". International Communist Current. 30 December 2004. http://en.internationalism.org/node/609.

- Đilas, Milovan (1983). The New Class: An Analysis of the Communist System (paperback ed.). San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. ISBN 0-15-665489-X.

- Đilas, Milovan (1969). The Unperfect Society: Beyond the New Class. New York City: Harcourt, Brace & World. ISBN 0-15-693125-7. https://archive.org/details/unperfectsociety00djil.

- Đilas, Milovan (1998). Fall of the New Class: A History of Communism's Self-Destruction (hardcover ed.). Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0-679-43325-2. https://archive.org/details/fallofnewclasshi00djil.

- Trotsky, Leon (1991). The Revolution Betrayed: What is the Soviet Union and Where is it Going? (paperback ed.). Detroit: Labor Publications. ISBN 0-929087-48-8. http://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/works/1936-rev/index.htm.

- Williams, Raymond (1985). "Capitalism". Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society. Oxford paperbacks (revised ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 52. ISBN 9780195204698. https://archive.org/details/keywordsvocabula00willrich. Retrieved 30 April 2017. "A new phrase, state-capitalism, has been widely used in mC20, with precedents from eC20, to describe forms of state ownership in which the original conditions of the definition – centralized ownership of the means of production, leading to a system of wage-labour – have not really changed."

- Engels, Friedrich (1880). Socialism: Utopian and Scientific. "III: Historical Materialism". Marxists Internet Archive. Retrieved 8 February 2020. https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1880/soc-utop/ch03.htm

- Cliff, Tony (1948). "The Theory of Bureaucratic Collectivism: A Critique". Marxists Internet Archive. Retrieved 8 February 2020. https://www.marxists.org/archive/cliff/works/1948/xx/burcoll.htm

- Mandel, Ernest (1979). "Why The Soviet Bureaucracy is not a New Ruling Class". Ernest Mandel Internet Archive. Retrieved 8 February 2020. http://www.ernestmandel.org/en/works/txt/1979/soviet_bureaucracy.htm

- Taaffe, Peter (1995). The Rise of Militant. "Preface". "Trotsky and the Collapse of Stalinism". Bertrams. "The Soviet bureaucracy and Western capitalism rested on mutually antagonistic social systems". ISBN:978-0906582473. https://www.socialistparty.org.uk/militant/

- Trotsky, Leon (1936). The Revolution Betrayed. Marxists Internet Archive. Retrieved 11 November 2019. https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1936/revbet/index.htm

- Trotsky, Leon (1938). "The USSR and Problems of the Transitional Epoch". In The Transitional Program. Marxists Internet Archive. Retrieved 11 November 2019. https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1938/tp/tia38.htm

- "The ABC of Materialist Dialectics". From "A Petty-Bourgeois Opposition in the Socialist Workers Party" (1939). Marxists Internet Archive. In Trotsky, Leon (1942). In Defense of Marxism. Retrieved 8 February 2020. https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1939/12/abc.htm

- Frank, Pierre (November 1951). "Evolution of Eastern Europe". Fourth International. Marxists Internet Archive. Retrieved 11 November 2019. https://www.marxists.org/history/etol/writers/frank/1951/08/eeurope.htm

- Grant, Ted (1978). "The Colonial Revolution and the Deformed Workers' States". The Unbroken Thread. Retrieved 21 June 2020. https://www.marxists.org/archive/grant/1978/07/colrev.htm

- Jayasuriya, Siritunga. "About Us". United Socialist Party. Retrieved 21 June 2020. http://lankasocialist.com/?page_id=8

- Walsh, Lynn (1991). Imperialism and the Gulf War. "Chapter 5". Socialist Alternative. Retrieved 21 June 2020. https://www.socialistalternative.org/imperialism-and-the-gulf-war-1990-91/introduction/