| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sirius Huang | -- | 988 | 2022-10-20 01:35:29 |

Video Upload Options

The Thaumarchaeota or Thaumarchaea (from the Ancient Greek:) are a phylum of the Archaea proposed in 2008 after the genome of Cenarchaeum symbiosum was sequenced and found to differ significantly from other members of the hyperthermophilic phylum Crenarchaeota. Three described species in addition to C. symbiosum are Nitrosopumilus maritimus, Nitrososphaera viennensis, and Nitrososphaera gargensis. The phylum was proposed in 2008 based on phylogenetic data, such as the sequences of these organisms' ribosomal RNA genes, and the presence of a form of type I topoisomerase that was previously thought to be unique to the eukaryotes. This assignment was confirmed by further analysis published in 2010 that examined the genomes of the ammonia-oxidizing archaea Nitrosopumilus maritimus and Nitrososphaera gargensis, concluding that these species form a distinct lineage that includes Cenarchaeum symbiosum. The lipid crenarchaeol has been found only in Thaumarchaea, making it a potential biomarker for the phylum. Most organisms of this lineage thus far identified are chemolithoautotrophic ammonia-oxidizers and may play important roles in biogeochemical cycles, such as the nitrogen cycle and the carbon cycle. Metagenomic sequencing indicates that they constitute ~1% of the sea surface metagenome across many sites. Thaumarchaeota-derived GDGT lipids from marine sediments can be used to reconstruct past temperatures via the TEX86 paleotemperature proxy, as these lipids vary in structure according to temperature. Because most Thaumarchaea seem to be autotrophs that fix CO2, their GDGTs can act as a record for past Carbon-13 ratios in the dissolved inorganic carbon pool, and thus have the potential to be used for reconstructions of the carbon cycle in the past.

1. Taxonomy

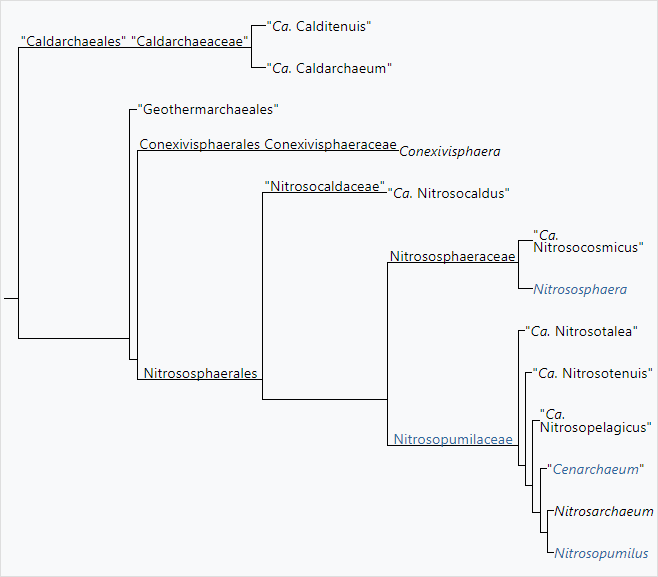

Phylogeny of Nitrososphaeria[1][2]

The currently accepted taxonomy is based on the List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature (LPSN)[3] and National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI)[4]

- Class Nitrososphaeria Stieglmeier et al. 2014[5] [Conexivisphaeria Kato et al. 2020]

- ?"Cenoporarchaeum" corrig. Zhang et al. 2019

- ?"Candidatus Giganthauma" Muller et al. 2010[6]

- Order Conexivisphaerales Kato et al. 2020

- Family Conexivisphaeraceae Kato et al. 2020

- Conexivisphaera Kato et al. 2020

- Family Conexivisphaeraceae Kato et al. 2020

- Order "Nitrosocaldales" de la Torre et al. 2008

- Family "Nitrosocaldaceae" Qin et al. 2016

- "Candidatus Nitrosocaldus" de la Torre et al. 2008

- Family "Nitrosocaldaceae" Qin et al. 2016

- Order Nitrososphaerales Stieglmeier et al. 2014

- Family Nitrososphaeraceae Stieglmeier et al. 2014

- "Candidatus Nitrosocosmicus" Lehtovirta-Morley et al. 2016

- Nitrososphaera Stieglmeier et al. 2014[7]

- Family Nitrososphaeraceae Stieglmeier et al. 2014

- Order "Cenarchaeales" Cavalier-Smith 2002 [8]

- Family "Cenarchaeaceae" DeLong & Preston 1996[9]

- Cenarchaeum DeLong & Preston 1996

- Family "Cenarchaeaceae" DeLong & Preston 1996[9]

- Order Nitrosopumilales Qin et al. 2017[10]

- Family Nitrosopumilaceae Qin et al. 2017

2. Metabolism

Thaumarchaea are important ammonia oxidizers in aquatic and terrestrial environments, and are the first archaea identified as being involved in nitrification.[20] They are capable of oxidizing ammonia at much lower substrate concentrations than ammonia-oxidizing bacteria, and so probably dominate in oligotrophic conditions.[21][22] Their ammonia oxidation pathway requires less oxygen than that of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria, so they do better in environments with low oxygen concentrations like sediments and hot springs. Ammonia-oxidizing Thaumarchaea can be identified metagenomically by the presence of archaeal ammonia monooxygenase (amoA) genes, which indicate that they are overall more dominant than ammonia oxidizing bacteria.[21] In addition to ammonia, at least one Thaumarchaeal strain has been shown to be able to use urea as a substrate for nitrification. This would allow for competition with phytoplankton that also grow on urea.[23] One study of microbes from wastewater treatment plants found that not all Thaumarchaea that express amoA genes are active ammonia oxidizers. These Thaumarchaea may be capable of oxidizing methane instead of ammonia, or they may be heterotrophic, indicating a potential for a diversity of metabolic lifestyles within the phylum.[24] Marine Thaumarchaea have also been shown to produce nitrous oxide, which as a greenhouse gas has implications for climate change. Isotopic analysis indicates that most nitrous oxide flux to the atmosphere from the ocean, which provides around 30% of the natural flux, may be due to the metabolic activities of archaea.[25]

Many members of the phylum assimilate carbon by fixing HCO3−.[26] This is done using a hydroxypropionate/hydroxybutyrate cycle similar to the Crenarchaea but which appears to have evolved independently. All Thaumarchaea that have been identified by metagenomics thus far encode this pathway. Notably, the Thaumarchaeal CO2-fixation pathway is more efficient than any known aerobic autotrophic pathway. This efficiency helps explain their ability to thrive in low-nutrient environments.[22] Some Thaumarchaea such as Nitrosopumilus maritimus are able to incorporate organic carbon as well as inorganic, indicating a capacity for mixotrophy.[26] At least two isolated strains have been identified as obligate mixotrophs, meaning they require a source of organic carbon in order to grow.[23]

A study has revealed that Thaumarchaeota are most likely the dominant producers of the critical vitamin B12. This finding has important implications for eukaryotic phytoplankton, many of which are auxotrophic and must acquire vitamin B12 from the environment; thus the Thaumarchaea could play a role in algal blooms and by extension global levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide. Because of the importance of vitamin B12 in biological processes such as the citric acid cycle and DNA synthesis, production of it by the Thaumarchaea may be important for a large number of aquatic organisms.[27]

3. Environment

Many Thaumarchaea, such as Nitrosopumilus maritimus, are marine and live in the open ocean.[26] Most of these planktonic Thaumarchaea, which compose the Marine Group I.1a Thaumarchaeota, are distributed in the subphotic zone, between 100m and 350m.[28] Other marine Thaumarchaea live in shallower waters. One study has identified two novel Thaumarchaeota species living in the sulfidic environment of a tropical mangrove swamp. Of these two species, Candidatus Giganthauma insulaporcus and Candidatus Giganthauma karukerense, the latter is associated with Gammaproteobacteria with which it may have a symbiotic relationship, though the nature of this relationship is unknown. The two species are very large, forming filaments larger than ever before observed in archaea. As with many Thaumarchaea, they are mesophilic.[29] Genetic analysis and the observation that the most basal identified Thaumarchaeal genomes are from hot environments suggests that the ancestor of Thaumarchaeota was thermophilic, and mesophily evolved later.[20]

References

- Mendler, K; Chen, H; Parks, DH; Hug, LA; Doxey, AC (2019). "AnnoTree: visualization and exploration of a functionally annotated microbial tree of life". Nucleic Acids Research 47 (9): 4442–4448. doi:10.1093/nar/gkz246. PMID 31081040. PMC 6511854. http://annotree.uwaterloo.ca/app/.

- "GTDB release 06-RS202". https://gtdb.ecogenomic.org/about#4%7C.

- J.P. Euzéby. "Thaumarchaeota". List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature (LPSN). https://lpsn.dsmz.de/phylum/thaumarchaeota. Retrieved 2021-03-20.

- Sayers. "Thaumarchaeota". National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) taxonomy database. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Taxonomy/Browser/wwwtax.cgi?mode=Tree&id=651137&lvl=3&keep=1&srchmode=1&unlock. Retrieved 2021-03-20.

- "Nitrososphaera viennensis gen. nov., sp. nov., an aerobic and mesophilic, ammonia-oxidizing archaeon from soil and a member of the archaeal phylum Thaumarchaeota". International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology 64 (Pt 8): 2738–52. August 2014. doi:10.1099/ijs.0.063172-0. PMID 24907263. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=4129164

- "First description of giant Archaea (Thaumarchaeota) associated with putative bacterial ectosymbionts in a sulfidic marine habitat.". Environmental Microbiology 12 (8): 2371–83. August 2010. doi:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02309.x. PMID 21966926. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2Fj.1462-2920.2010.02309.x

- "Genome sequence of Candidatus Nitrososphaera evergladensis from group I.1b enriched from Everglades soil reveals novel genomic features of the ammonia-oxidizing archaea". PLOS ONE 9 (7): e101648. 7 July 2014. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0101648. PMID 24999826. Bibcode: 2014PLoSO...9j1648Z. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=4084955

- "The neomuran origin of archaebacteria, the negibacterial root of the universal tree and bacterial megaclassification". International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology 52 (Pt 1): 7–76. January 2002. doi:10.1099/00207713-52-1-7. PMID 11837318. https://dx.doi.org/10.1099%2F00207713-52-1-7

- "A psychrophilic crenarchaeon inhabits a marine sponge: Cenarchaeum symbiosum gen. nov., sp. nov". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 93 (13): 6241–6. June 1996. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.13.6241. PMID 8692799. Bibcode: 1996PNAS...93.6241P. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=39006

- "Isolation of an autotrophic ammonia-oxidizing marine archaeon". Nature 437 (7058): 543–6. September 2005. doi:10.1038/nature03911. PMID 16177789. Bibcode: 2005Natur.437..543K. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038%2Fnature03911

- "Cultivation of an obligate acidophilic ammonia oxidizer from a nitrifying acid soil". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 108 (38): 15892–7. September 2011. doi:10.1073/pnas.1107196108. PMID 21896746. Bibcode: 2011PNAS..10815892L. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3179093

- "Enrichment and genome sequence of the group I.1a ammonia-oxidizing Archaeon "Ca. Nitrosotenuis uzonensis" representing a clade globally distributed in thermal habitats". PLOS ONE 8 (11): e80835. 2013. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0080835. PMID 24278328. Bibcode: 2013PLoSO...880835L. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3835317

- "A novel ammonia-oxidizing archaeon from wastewater treatment plant: Its enrichment, physiological and genomic characteristics". Scientific Reports 6: 23747. March 2016. doi:10.1038/srep23747. PMID 27030530. Bibcode: 2016NatSR...623747L. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=4814877

- "Genomic and proteomic characterization of "Candidatus Nitrosopelagicus brevis": an ammonia-oxidizing archaeon from the open ocean". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 112 (4): 1173–8. January 2015. doi:10.1073/pnas.1416223112. PMID 25587132. Bibcode: 2015PNAS..112.1173S. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=4313803

- "Genome of a low-salinity ammonia-oxidizing archaeon determined by single-cell and metagenomic analysis". PLOS ONE 6 (2): e16626. February 2011. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0016626. PMID 21364937. Bibcode: 2011PLoSO...616626B. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3043068

- "Genome sequence of an ammonia-oxidizing soil archaeon, "Candidatus Nitrosoarchaeum koreensis" MY1". Journal of Bacteriology 193 (19): 5539–40. October 2011. doi:10.1128/JB.05717-11. PMID 21914867. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3187385

- "Draft genome sequence of an ammonia-oxidizing archaeon, "Candidatus Nitrosopumilus koreensis" AR1, from marine sediment". Journal of Bacteriology 194 (24): 6940–1. December 2012. doi:10.1128/JB.01857-12. PMID 23209206. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3510587

- "Genome sequence of "Candidatus Nitrosopumilus salaria" BD31, an ammonia-oxidizing archaeon from the San Francisco Bay estuary". Journal of Bacteriology 194 (8): 2121–2. April 2012. doi:10.1128/JB.00013-12. PMID 22461555. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3318490

- "Physiological and genomic characterization of two novel marine thaumarchaeal strains indicates niche differentiation". The ISME Journal 10 (5): 1051–63. May 2016. doi:10.1038/ismej.2015.200. PMID 26528837. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=4839502

- "Spotlight on the Thaumarchaeota". The ISME Journal 6 (2): 227–30. February 2012. doi:10.1038/ismej.2011.145. PMID 22071344. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3260508

- "The Thaumarchaeota: an emerging view of their phylogeny and ecophysiology". Current Opinion in Microbiology 14 (3): 300–6. June 2011. doi:10.1016/j.mib.2011.04.007. PMID 21546306. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3126993

- "Ammonia-oxidizing archaea use the most energy-efficient aerobic pathway for CO2 fixation". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 111 (22): 8239–44. June 2014. doi:10.1073/pnas.1402028111. PMID 24843170. Bibcode: 2014PNAS..111.8239K. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=4050595

- Qin, Wei; Amin, Shady A.; Martens-Habbena, Willm; Walker, Christopher B.; Urakawa, Hidetoshi; Devol, Allan H.; Ingalls, Anitra E.; Moffett, James W. et al. (2014). "Marine ammonia-oxidizing archaeal isolates display obligate mixotrophy and wide ecotypic variation". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111 (34): 12504–12509. doi:10.1073/PNAS.1324115111. ISSN 0027-8424. PMID 25114236. Bibcode: 2014PNAS..11112504Q. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=4151751

- "Thaumarchaeotes abundant in refinery nitrifying sludges express amoA but are not obligate autotrophic ammonia oxidizers". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 108 (40): 16771–6. October 2011. doi:10.1073/pnas.1106427108. PMID 21930919. Bibcode: 2011PNAS..10816771M. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3189051

- Santoro, A. E.; Buchwald, C.; McIlvin, M. R.; Casciotti, K. L. (2011-09-02). "Isotopic Signature of N2O Produced by Marine Ammonia-Oxidizing Archaea". Science 333 (6047): 1282–1285. doi:10.1126/science.1208239. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 21798895. Bibcode: 2011Sci...333.1282S. https://dx.doi.org/10.1126%2Fscience.1208239

- "Nitrosopumilus maritimus genome reveals unique mechanisms for nitrification and autotrophy in globally distributed marine crenarchaea". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 107 (19): 8818–23. May 2010. doi:10.1073/pnas.0913533107. PMID 20421470. Bibcode: 2010PNAS..107.8818W. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2889351

- "Aquatic metagenomes implicate Thaumarchaeota in global cobalamin production". The ISME Journal 9 (2): 461–71. February 2015. doi:10.1038/ismej.2014.142. PMID 25126756. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=4303638

- "Stable carbon isotope ratios of intact GDGTs indicate heterogeneous sources to marine sediments". Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 181: 18–35. 2016. doi:10.1016/j.gca.2016.02.034. Bibcode: 2016GeCoA.181...18P. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.gca.2016.02.034

- "First description of giant Archaea (Thaumarchaeota) associated with putative bacterial ectosymbionts in a sulfidic marine habitat". Environmental Microbiology 12 (8): 2371–83. August 2010. doi:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02309.x. PMID 21966926. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2Fj.1462-2920.2010.02309.x